Abstract

BACKGROUND:

With the advancement of imaging technology, focal therapy (FT) has been gaining acceptance for the treatment of select patients with localized prostate cancer (PCa). We aim to provide details of a formal physician consensus on the utilization of FT for patients with PCa who are discontinuing active surveillance (AS).

METHODS:

A three-stage Delphi consensus in PCa and FT was conducted. Consensus was defined as agreement by ⩾80% of physicians. An in-person meeting was attended by 17 panelists to formulate the consensus statement.

RESULTS:

Fifty-six respondents participated in this interdisciplinary consensus study (82% urologist, 16% radiologist, 2% radiation oncology). The participants confirmed that there is a role for FT in men discontinuing AS (48% strongly agree, 39% agree). The benefit of FT over radical therapy for men coming off AS is: less invasive (91%), has a greater likelihood to preserve erectile function (91%), has a greater likelihood to preserve urinary continence (91%), has less side effects (86%) and has early recovery post-treatment (80%). Patients will need to undergo mpMRI of the prostate and/or a saturation biopsy to determine if they are potential candidates for FT. Our limitations include respondent’s biases and that the participants of this consensus may not represent the larger medical community.

CONCLUSIONS:

FT can be offered to men coming off AS between the age of 60–80 with grade group 2 localized cancer. This consensus from a multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional, international expert panel provides a contemporary insight utilizing FT for PCa in select patients who are discontinuing AS.

Keywords: Localized Prostate Cancer, Focal Therapy, Partial Gland Ablation, Active Surveillance

Introduction

Low grade localized prostate cancer (PCa) has a long natural course, has limited metastatic potential,[1, 2] and is widely considered to be clinically insignificant.[3, 4] The growth rate of many of these cancers is extremely slow.[5] Active surveillance (AS) is the standard of care for these men.[6, 7] In fact, multiple prospective phase 2 trials with follow up ranging from 10 to 29 years have shown cancer-specific survival rates comparable to series of patients treated with radical prostatectomy.[8–11] Over time, some of these men are later reclassified to a higher risk disease category (usually grade progression) and eventually receive definitive therapy. These therapies are associated with well-known quality-of-life side-effects.

In recent years, advancements in imaging and targeted biopsy have created the opportunity for an informed implementation of focal treatment of PCa.[12–14] Focal therapy (FT), or partial gland ablation, entails applying some form of energy to the area of the prostate that harbors clinically significant cancer, with the goal of achieving less morbidity yet similar cancer control compared to whole-gland approaches.[15–18] However, there is no evidence in the literature specifically pertaining to FT for men discontinuing AS.

In topics where there is limited or little high quality evidence, the development of expert consensus is a valuable approach to address specific topics where opinion from experts becomes important.[19] The Delphi method was conceived in the 1950s by Olaf Helmer and Norman Dalkey to allow experts to arrive at a group consensus by providing them with multiple rounds of questionnaires, as well as the group’s response before each subsequent round. In this report, we sought to develop a contemporary expert consensus on the utilization of FT for appropriate men with PCa who are discontinuing AS.

Methods

An online Delphi survey among prostate cancer experts around the world was conducted.[20, 21] The web-based questionnaire was constructed by the use of Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com, San Mateo, California, USA) that was accessed between January 1st, 2020 and February 15th 2020.

The participants were sent the questionnaire electronically in three consecutive rounds. At each subsequent round, the aggregate results of the prior round were presented anonymously, and the participants allowed to modify their responses. Feedback and comments provided by experts were utilized to adjust/refine existing questions or explore controversial topics in greater depth. Checkboxes were used for the demographics portion of the survey and multiple selections were possible. Therefore, total responses could exceed 100%. The final questionnaire is listed in Appendix 1. Achieving consensus was defined by having ≥80% agreement for each question. [22, 23]

Participant selection

Participants were identified and invited to participate based on prior presentations at plenary sessions at previous international FT symposium conferences, the American Urological Association conference, the European Association of Urology congress, clinical and research interest in PCa by means of reputation, authorship on review topics or peer recommendation (Appendix 2). These physicians have expertise in the management of patients with prostate cancer via active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, imaging, targeting, focal therapy or a combination of the above. The experts were selected to represent professional groups that directly influence patient care and would benefit from clinical practice guidelines. Patients, nurses and administrators were not included as participants as the goal of the study was to develop recommendations for focal therapy for patients coming off active surveillance, based on a clinician’s perspective. The participants consisted of urologic surgeons, radiologists, interventional radiologists and radiation oncologist.

Systematic review of the literature

A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify best practice evidence for clinical guidelines development. A PubMed search was performed up to January 2nd 2020. The detailed search terms, filters and exclusions are presented in Figure 1. The search strategy consisted of combined headings and keywords for “prostate cancer” and “active surveillance” and “focal therapy” (see textbox in Figure 1). Reference lists from included publications were also screened to identify additional papers.

Figure 1:

Search terms for literature review.

Round 1

The first round of the Delphi consensus contained 27 questions. Checkboxes were used rather than multiple choices to allow the selection of more than one answer. A 5-point Likert scale was utilized rather than ‘yes-no’ responses to evaluate the participant’s level of agreement. Participants were also given the opportunity to provide comments and suggest additional items that may not have been included when developing the initial list of statements. The intention of round one was to address any redundancies, issues regarding comprehension or syntax of each statement and to allow the participants to provide feedback to improve the survey. Statements not meeting 80% agreement were modified according to the feedback provided by the participants and redistributed for round 2.

Round 2

The list of statements not meeting consensus from round 1 was emailed to all participants. In round 2, the participants were presented with a similar voting method to round 1, except that each question began with the group scores from round 1. Hence, the participants could reflect upon the group results and change/modify/take into account their peers answer accordingly, while preserving the anonymity of their/all responses. Final responses were analyzed as described for round 1, and statements not achieving consensus were retained for round 3.

Round 3

The list of statements not achieving consensus from round 2 was emailed to all participants. Similar to round 2, the participants were presented with the group results and allowed to change/modify their answer accordingly. Final responses were analyzed similar to previous rounds and statements not achieving consensus were retained for the face to face meeting.

Face to face meeting

The face-to-face meeting occurred at the 12th International Symposium of Focal Therapy and Imaging in Prostate and Kidney Cancer in Washington DC on February 10th, 2020. This was a work meeting to draft and finalize the consensus and voting occurred using a show of hands. The face-to-face meeting was mediated by a meeting chair (WPT) and the panel members discussed the remaining statements until agreement was achieved to retain, eliminate or modify the statements from the final consensus document. The meeting was recorded for documentation purposes.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as percentages. Data was analyzed using SurveyMonkey Inc platform at www.surveymonkey.com.

Results

Participant selection

Ninety-one participants were invited to participate in the Delphi consensus, and 56 filled out the initial survey. Questionnaires were submitted in three rounds, and the response rate for the second and third round were 56/56 (100%) and 49 (88%), respectively. A total of 17 panelists attended the face-to-face meeting to draft the consensus (Appendix 2).

Systematic review of the literature

The literature search was performed to identify best practice evidence of clinical practice guidelines for the utilization of FT for patients discontinuing AS. The search identified 80 publications. Of these, 18 were selected based on title and abstracts. None were provided to the core group given there is no published literature pertaining to data on utilization of FT for men discontinuing AS (Figure 1).

Results from the consensus project

Demographics of respondents

Forty (71%) of participants self-identified as a urologic oncologist, followed by 11 (20%) identifying as a general urologist and 7 (13%) identifying as an endourologist and/or radiologist, respectively (Table 1). The majority of participants routinely practice AS and are considered high-volume conventional/whole gland proceduralists.

Table 1:

Demographics of respondents

| Specialty | |

| General Urology | 11 (20%) |

| Urologic Oncology | 40 (71%) |

| Endourology | 7 (13%) |

| Radiation Oncology | 1 (2%) |

| Interventional Radiology | 1 (2%) |

| Radiology | 9 (16%) |

|

| |

| Practice type | |

| Academics | 51 (91%) |

| Semi-academic | 2 (4%) |

| Hospital Employed | 4 (7%) |

| Private Practice | 5 (9%) |

| Government | 4 (7%) |

| Others | 1 (2%) |

|

| |

| Practice setting | |

| Urban, major city (>750k) | 46 (82%) |

| Urban, large city (500–750k) | 5 (9%) |

| Small city/suburban (100–500k) | 5 (9%) |

| Rural (<100k) | 0 |

|

| |

| Procedures performed | |

| HIFU | 23 (41%) |

| Cryoablation | 25 (45%) |

| Laser ablation | 16 (29%) |

| Irreversible electroporation | 7 (13%) |

| Photodynamic therapy | 8 (14%) |

| Brachytherapy | 24 (43%) |

| External beam radiation | 25 (25%) |

| Open radical prostatectomy | 19 (34%) |

| Laparoscopic/robotic prostatectomy | 44 (79%) |

| Others | 5 (9%) |

|

| |

| Focal therapy procedures performed/year, Median (IQR) | 20 (10/35) |

Responses may total to more than 100% given the items are not mutually exclusive

IQR: Interquartile range

Role of FT in men discontinuing AS

The participants agree that there may be a role for FT in men discontinuing AS (48% strongly agree, 39% agree). The respondents’ rationale for recommending FT over radical therapy, in select men discontinuing AS, was that FT is less invasive (91%), has a greater likelihood of preserving erectile function (91%), has a greater likelihood of preserving urinary continence (91%), has less side effects (86%) and has early recovery post-treatment (80%). Given the appropriate clinical circumstances and assuming a biopsy proven MRI-targetable lesion, the participants agreed that a physician may consider FT when upgrading from grade group 1 to 2 occurs on fusion biopsy. The group agreed that FT for men discontinuing AS should be considered between age 60 and 80 (88% selected 60–69 and 89% selected 70–80).

Workup prior to FT

There was no consensus pertaining to PSA criteria that might affect the decision to recommend FT. The panel recommended that a PSA increase would prompt re-interrogation of the prostate, but not prompt a decision to perform FT (100%). The panel agreed that a molecular biomarker indicating high risk of adverse pathology might influence the physician to re-interrogate the prostate, but not necessarily prompt a decision to perform FT (100%).

In terms of the type of biopsy technique used to evaluate a patient currently on AS who is considering FT, the group agreed that the patient should undergo an MRI targeted biopsy plus 12 core systematic biopsy (88%). A consensus could not be reached pertaining to a metastatic workup, but the panel voted (face-to-face meetnig) that a metastatic workup is not required for patients with low risk and intermediate favorable risk based on the NCCN guidelines (100%).[24] If a patient is unable to undergo a mpMRI, the group agreed that a 3D mapping biopsy of the prostate that demonstrates a reasonably localized tumor burden based on pathological analysis is sufficient for FT (85%). In a patient who does not have an MRI-visible lesion, the group agreed that they would not offer the patient FT if the patient only underwent a 12-core random biopsy (80%).

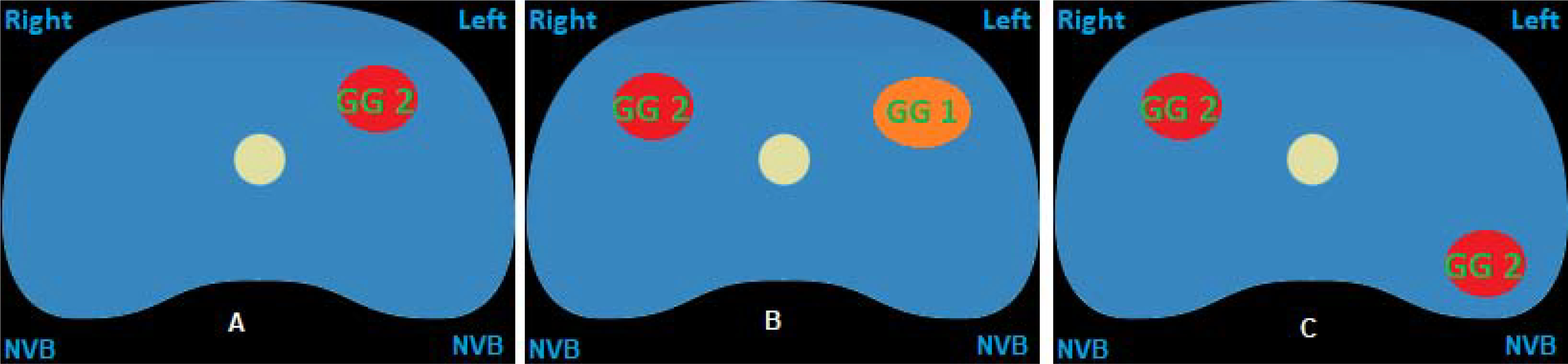

Focal therapy margin

For the scenario-based questions, Figure 2A shows a single grade group 2 lesion in the prostate, away from the neurovascular bundle; Figure 2B shows grade group 1 and 2 lesions in the anterior prostate, away from the neurovascular bundles; Figure 2C shows two grade group 2 lesions, one being in the vicinity of the neurovascular bundle and the other in the anterior prostate. The group agreed that FT could be offered to Figure 2A and 2B. However, the group could not come to a consensus on the ideal template for FT for clinical scenarios illustrated by both/either Figure 2A and 2B. There was no consensus if FT should be offered for the clinical scenario in Figure 2C. However, the panel decided that given the multi-focality of clinically significant disease, this would not represent an ideal candidate for FT (100%).

Figure 2.

A: MRI lesion and biopsy results for question 15 & 16

Figure 2B: MRI lesion and biopsy results for question 17 & 18

Figure 2C: MRI lesion and biopsy results for question 19

Seven questions were omitted from the final report as they were part of a multiple-step question for the scenario-based questions. These questions pertained to the type of metastatic workup, if applicable, prior to FT, and ablation template for different scenarios that the panel voted as not representing ideal candidates for FT. A summary of the consensus statements is shown on Table 2.

Table 2:

Summary of consensus statements

| Role and rationale of focal therapy |

| - There is a role for focal therapy in select men discontinuing active surveillance. |

| - Compared to radical whole gland treatment, Focal therapy: |

| 1. Is less invasive |

| 2. Has greater likelihood to preserve erectile function |

| 3. Has greater likelihood to preserve urinary continence |

| 4. Is associated with earlier recovery post-treatment |

|

|

| Patient demographics and disease factors |

| - For age 60 – 80, should consider focal therapy when coming off active surveillance. |

| - Gleason 3+4 cancer (grade group 2) with localized disease |

| - Men with PSA <10 ng/mL are ideally suited for focal therapy |

| - Patients with multi-focal grade group 2 or higher lesions are not ideal candidates for focal therapy. |

|

|

| Work up |

| - An increasing PSA or a biomarker test indicating higher risk of adverse pathology should not prompt focal therapy, but instead prompt re-interrogation of the prostate. |

| - mpMRI/US guided fusion biopsy and a 12-core systematic biopsy is recommended for men on active surveillance prior to considering focal therapy. |

| - If unable to undergo mpMRI, patients will require a 3D mapping biopsy of the prostate to determine if they are a candidate for focal therapy |

| - No metastatic workup is usually required prior to considering focal therapy |

|

|

| Ablation template |

| - There was no consensus on the ideal template for focal therapy. |

PSA: Prostate-specific antigen; mpMRI: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

Discussion

With the improvement in imaging modalities for PCa, FT has been introduced as a novel treatment option for select men with localized PCa. However, the majority of FT trials included grade group 1 patients (who would be more appropriately managed with AS), and no study to date has evaluated the use of FT for men discontinuing AS.[15, 25, 26] In this consensus, we aimed to explore the use of FT for men with PCa coming off AS. Most men on AS initially have grade group 1 or limited grade group 2 disease. We found that the majority of participants agreed that there is a role for FT in this cohort in the appropriately-selected patient.

Participants of the survey agreed that a patient with a solitary Gleason 3+4 lesion (grade group 2) is the ideal candidate for FT and that most of these lesions can be safely and effectively ablated. However, there was no clear consensus on the ideal treatment template for such a lesion. In fact, even after the panel convened in person (face-to-face meeting), we were unable to achieve a consensus on the ideal template for treatment. We believe this is because different energy sources result in different ablation margins. Also, FT provides the physician with the ability to individualize a therapy plan based on the location, size and number of tumor(s) within the prostate. Such customization will result in a wider spectrum of opinion as to what treatment may be best when one attempts to balance preservation of genitourinary function with cancer control. Also weighing in heavily with an individualized treatment approach is patient preference, and this consensus did not aim to take this important consideration into account. The panel also felt that patients with multiple clinically significant lesions (≥grade group 2) that are not located within the anterior prostate are not ideal candidates for FT (Figure 2C).

Five questions did not achieve consensus during the first three rounds of the Delphi Consensus. The seventeen participants on the panel were able to achieve consensus for three of the questions. The panel strongly believed that PSA and the result of any biomarker should not influence the decision to perform FT in an absolute sense, but these markers should guide the decision to undertake further evaluation. A biomarker result suggesting adverse pathology should prompt an mpMRI and eventually a fusion-guided biopsy and 12 core biopsy. The panel also agreed that no metastatic workup is required under usual circumstances in patients who are candidates for FT, given a metastatic workup is only warranted in patients with intermediate unfavorable or high risk cancer.[24, 27] Those patients displaying excessive risk should not be considered for FT in the primary setting as traditional management options would likely serve them better. The two questions that did not reach consensus were those regarding the ideal choice of templates for patients considering FT (Figure 2A and 2B).

Two prior consensus addressed surveillance following FT.[28, 29] There was consensus that PSA does not currently offer any reliable, reproducible data in the follow-up after FT. Although the doubling time of PSA may be an important criterion predicting treatment failure, it does not represent a good parameter for biochemical recurrence. Tay et al performed a systematic review pertaining to surveillance after prostate FT and concluded that mpMRI should be performed at 3–6 months, 12–24 months and at 5 years after FT.[30] They also suggested that targeted biopsy of the treated zone and any suspicious lesion seen on MRI should be performed at 3–6 months, and a systematic biopsy should be performed at 12–24 months and again at 5 years.[30]

This consensus has several limitations and should be interpreted within its context. First, this was a selected group of clinicians who have an interest in FT, that may reflect selection bias. However, the overwhelming majority of the experts involved in the consensus have a high-volume clinical practice treating men with prostate cancer using conventional therapies such as radical prostatectomy, brachytherapy, AS and ablation. The group’s opinion may not be representative of the larger medical community. Also, the in-person meeting could have been driven by more dominant opinions. There was also no patient involvement when developing the consensus. Finally, the repetition and reformulation of questions and answer choices by the project leaders may also incur bias, an inherent limitation of the Delphi method. Despite these limitations, this consensus reflects the opinion of a multi-disciplinary, forward-thinking global community with many members involved in traditional radical therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Conclusion

FT in men with localized PCa discontinuing AS is gaining wider acceptance. This consensus report provides context and guidance that a minimally-invasive gland and function-preserving strategy should be considered as a potential next step. In the appropriate clinical context, PCa specialists should contemplate treating an image-targetable tumor(s) in these men rather than resorting to whole gland therapy with its attendant side effects. The advantages are an improved quality life. For men with GG 2 PCa whose mortality risk is low, this is an extremely appealing prospect, particularly to patients who may not require the most aggressive forms of treatment.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1: Results of consensus statements.

Appendix 2: All registered participants for the Delphi Consensus.

Supplementary Figure 2: Ablation template for question 18.

Supplementary Figure 1: Ablation template for question 16.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

1. WPT is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant (T32-CA093245).

2. TJP has a training consultant agreement with Endocare.

Abbreviations

- AS

Active surveillance

- FT

Focal therapy

- HIFU

High intensity focused ultrasound

- mpMRI

Multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NCCN

National comprehensive cancer network

- PCa

Prostate Cancer

- PSA

Prostate specific antigen

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Eggener SE, Scardino PT, Walsh PC, Han M, Partin AW, Trock BJ, et al. Predicting 15-year prostate cancer specific mortality after radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 2011;185:869–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ross HM, Kryvenko ON, Cowan JE, Simko JP, Wheeler TM, Epstein JI. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) </=6 have the potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? The American journal of surgical pathology. 2012;36:1346–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johansson J-E, Andrén O, Andersson S-O, Dickman PW, Holmberg L, Magnuson A, et al. Natural History of Early, Localized Prostate Cancer. Jama. 2004;291:2713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dall’Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C, Carroll PR, Carter HB, Cooperberg MR, et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. European urology. 2012;62:976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Popiolek M, Rider JR, Andrén O, Andersson S-O, Holmberg L, Adami H-O, et al. Natural History of Early, Localized Prostate Cancer: A Final Report from Three Decades of Follow-up. European urology. 2013;63:428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, Chen RC, Crispino T, Fontanarosa J, et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: Risk Stratification, Shared Decision Making, and Care Options. The Journal of urology. 2018;199:683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. European urology. 2017;71:618–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Holding P, et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:1415–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, Taari K, Busch C, Nordling S, et al. Radical Prostatectomy or Watchful Waiting in Prostate Cancer - 29-Year Follow-up. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379:2319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, Andriole GL, Culkin D, Wheeler T, et al. Follow-up of Prostatectomy versus Observation for Early Prostate Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;377:132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, Barry MJ, Aronson WJ, Fox S, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:203–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ahdoot M, Wilbur AR, Reese SE, Lebastchi AH, Mehralivand S, Gomella PT, et al. MRI-Targeted, Systematic, and Combined Biopsy for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382:917–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan WP, ElShafei A, Aminsharifi A, Khalifa AO, Polascik TJ. Salvage Focal Cryotherapy Offers Similar Short-term Oncologic Control and Improved Urinary Function Compared With Salvage Whole Gland Cryotherapy for Radiation-resistant or Recurrent Prostate Cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, Panebianco V, Mynderse LA, Vaarala MH, et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;378:1767–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ahdoot M, Lebastchi AH, Turkbey B, Wood B, Pinto PA. Contemporary treatments in prostate cancer focal therapy. Current opinion in oncology. 2019;31:200–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Aminsharifi A, de la Rosette J, Polascik TJ. Focal therapy of prostate and kidney cancer. Current opinion in urology. 2018;28:491–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tay KJ, Schulman AA, Sze C, Tsivian E, Polascik TJ. New advances in focal therapy for early stage prostate cancer. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2017;17:737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Valerio M, Cerantola Y, Eggener SE, Lepor H, Polascik TJ, Villers A, et al. New and Established Technology in Focal Ablation of the Prostate: A Systematic Review. European urology. 2017;71:17–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1995;311:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management science. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dalkey NC. The Delphi method: An experimental study of group opinion. RAND CORP SANTA MONICA CALIF; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67:401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing research. 1986;35:382–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate Cancer (Version 1.2020). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bone.pdf. Accessed February 27.

- [25].Lee T, Mendhiratta N, Sperling D, Lepor H. Focal laser ablation for localized prostate cancer: principles, clinical trials, and our initial experience. Rev Urol. 2014;16:55–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Valerio M, Ahmed HU, Emberton M, Lawrentschuk N, Lazzeri M, Montironi R, et al. The role of focal therapy in the management of localised prostate cancer: a systematic review. European urology. 2014;66:732–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cancer NCCNB. (Version 1.2020)..

- [28].Muller BG, van den Bos W, Brausi M, Fütterer JJ, Ghai S, Pinto PA, et al. Follow-up modalities in focal therapy for prostate cancer: results from a Delphi consensus project. World journal of urology. 2015;33:1503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Scheltema MJ, Tay KJ, Postema AW, de Bruin DM, Feller J, Futterer JJ, et al. Utilization of multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging in clinical practice and focal therapy: report from a Delphi consensus project. World journal of urology. 2017;35:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tay KJ, Amin MB, Ghai S, Jimenez RE, Kench JG, Klotz L, et al. Surveillance after prostate focal therapy. World journal of urology. 2019;37:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Results of consensus statements.

Appendix 2: All registered participants for the Delphi Consensus.

Supplementary Figure 2: Ablation template for question 18.

Supplementary Figure 1: Ablation template for question 16.