Abstract

Over the last decades, the Indian government has adopted several strategies and programmes to encourage institutional childbirth and reduce maternal mortality. However, ensuring institutional delivery does not of itself ensure safe and dignified delivery and there are frequently episodes of violence during childbirth. Obstetric violence has long-term adverse effects on the health and well-being of women. The present study attempts to understand the nature of obstetric violence and the organisational contexts in which patterns of violent behaviours and actions emerge and are reproduced, contributing to obstetric violence. A database search for literature was conducted on PubMed and studies on women’s experience during childbirth in health facilities in India were selected, based on the inclusion criteria. The present review’s findings show that the most prevalent form of obstetric violence is verbal abuse followed by physical abuse and other dehumanising behaviour. Women from lower castes, Muslim communities, and low-income families were shown to be more likely to encounter dehumanising and neglectful behaviour from care providers in public health facilities. Obstetric violence during childbirth arises from encounters between care providers and women at an individual level, health system failures, and an abusive institutional atmosphere and culture. The abusive environment in health facilities fosters fear about facility care among women, contributes to worsened health outcomes, and deters women from further utilisation of health care services. Therefore, along with expanding institutional births and access to emergency obstetric care, measures should be taken to ensure dignified and caring treatment of women during childbirth.

Keywords: obstetric violence, mistreatment, disrespect and abuse, childbirth, India

Résumé

Ces dernières décennies, le Gouvernement indien a adopté plusieurs stratégies et programmes pour encourager l’accouchement en milieu hospitalier et réduire la mortalité maternelle. Néanmoins, garantir un accouchement en milieu hospitalier ne suffit pas en soi à garantir une naissance sûre et digne, et de fréquents épisodes de violences ont été signalés pendant l’accouchement. Les violences obstétricales ont des conséquences à long terme sur la santé et le bien-être des femmes. La présente étude tente de comprendre la nature des violences obstétricales et les contextes organisationnels dans lesquels des modes d’actions et de comportements violents apparaissent et sont reproduits, contribuant aux violences obstétricales. Une recherche de publications a été menée dans la base de données PubMed et des études sur l’expérience des femmes pendant l’accouchement dans des centres de santé en Inde ont été retenues sur la base des critères d’inclusion. Les conclusions de l’étude montrent que la forme la plus prévalente de violences obstétricales est la maltraitance verbale suivie de mauvais traitements physiques et d’autres comportements déshumanisants. Il en ressort que les femmes issues de castes inférieures, de communautés musulmanes et de familles à faible revenu risquaient davantage de se heurter à un comportement déshumanisant et négligent de la part des prestataires de soins dans les établissements publics. Les violences obstétricales pendant l’accouchement résultent de rencontres entre des prestataires de soins et des femmes à un niveau individuel, de défaillances du système de santé, ainsi que d’une atmosphère et d’une culture institutionnelles violentes. L’environnement violent dans les établissements de santé favorise la peur des soins en institution parmi les femmes, aggrave l’état de santé et décourage les femmes de recourir à nouveau aux services de santé. Par conséquent, tout en étendant les naissances en milieu hospitalier et en élargissant l’accès aux soins obstétricaux d’urgence, des mesures devraient être prises pour garantir un traitement digne et bienveillant des femmes pendant l’accouchement.

Resumen

En las últimas décadas, el gobierno de India ha adoptado varias estrategias y programas para fomentar el parto institucional y reducir la mortalidad materna. Sin embargo, garantizar el parto institucional no garantiza un parto seguro y digno, y hay frecuentes episodios de violencia durante el parto. La violencia obstétrica tiene efectos adversos a largo plazo en la salud y en el bienestar de las mujeres. El presente estudio pretende entender la naturaleza de la violencia obstétrica y los contextos institucionales en que surgen y se reproducen patrones de comportamientos y actos violentos, lo cual contribuye a la violencia obstétrica. Se realizó una búsqueda de la literatura en la base de datos de PubMed y se incluyeron estudios sobre la experiencia de las mujeres durante el parto en establecimientos de salud de India, según los criterios de inclusión. Los hallazgos de la presente revisión muestran que la forma más prevalente de violencia obstétrica es maltrato verbal, seguido de maltrato físico y otros comportamientos deshumanizantes. Se comprobó que las mujeres de castas inferiores, comunidades musulmanas y familias de bajos ingresos son más propensas a enfrentar comportamientos deshumanizantes y negligentes por parte de prestadores de servicios en establecimientos de salud pública. La violencia obstétrica durante el parto surge a causa de encuentros entre prestadores de servicios y las mujeres a nivel individual, fallas en el sistema de salud y un ambiente y cultura institucionales abusivos. El ambiente abusivo en los establecimientos de salud fomenta temor entre las mujeres respecto a la atención que reciben, contribuye a empeorar los resultados de salud y disuade a las mujeres de continuar utilizando los servicios de salud. Por ello, además de aumentar el número de partos institucionales y ampliar el acceso a los cuidados obstétricos de emergencia, es necesario adoptar medidas para garantizar el tratamiento digno y amable de las mujeres durante el parto.

Introduction

Despite the growing efforts to minimise death during childbirth, maternal mortality remains a major cause of death across the world. In the last decade, India has successfully reduced maternal mortality from a high of 254 per 100,000 live births in 2004–2006 to 130 per 100,000 live births in 2015, accounting for 17% of all maternal deaths worldwide.1 The Indian government introduced several policies and health system reforms to reduce maternal mortality, primarily promoting institutional delivery and antenatal care. These policies were helpful to some extent in improving the proportion of institutional deliveries, maternal health outcomes, and reducing maternal mortality ratios, but ensuring the quality of obstetric care remains a major concern. There is substantial evidence of various disrespectful and aggressive practices that women encounter in obstetric care facilities, particularly during childbirth, which discourage them from using institutional health care in the future.2 Evidence of mistreatment and aggressive behaviour by healthcare providers towards women during childbirth is found in both low- and high-income nations.3

Violence against women during childbirth, known as obstetric violence, is a multifaceted and complex human rights infringement and public health problem with adverse health consequences. Some studies have described obstetric violence as disrespect and abuse, dehumanising behaviour, and mistreatment. The violent behaviours include verbal and physical abuse, privacy breaches, stigma and prejudice, unethical healthcare procedures, abandonment, and negligence.4 Although researchers have used different definitions and classifications of violence against women, they link mistreatment and gender-based violence. The feminist scholar Shabot argues that violence against women during childbirth is gender-based violence, “directed at women because they are women”.5 The movement against “obstetric violence” originated from feminists’ critique of excessive medicalisation of maternal care and call for humanised childbirth. The humanised birth movement focused on de-medicalising birth, arguing that “birth is a natural phenomenon over which women should have control, and medical interventions should only be used when required”.6

Several studies have shown that many women who face obstetric violence in India come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.7,8 Such women have to resort to public facilities for childbirth; they expect such behaviour and therefore do not think it is abnormal, illegal, or ethically wrong. In India, social status influences the quality of medical treatment and the experiences of Indian upper-middle-class women with institutional births vary substantially from those of their working-class counterparts.9 It is, therefore, also essential to understand the intersectionality of caste, class, religion, and deep-rooted patriarchy in the context of obstetric violence. Interactions between medical personnel and users of state facilities are marked by significant power imbalances.10

Despite the growing body of literature on obstetric violence globally, the literature in the Indian setting is scattered. The present study, therefore, systematically reviewed the available literature on obstetric violence in the Indian context. The review aimed to examine the evidence on different forms of obstetric violence and explore the organisational context in which behaviours and actions emerge and manifest as obstetric violence within healthcare facilities.

Methods

The present study is based on a systematic review of literature on obstetric violence in India. The PRISMA-P 2015 statement is used for the methodological framework.

Literature search strategy

The database search was conducted on PubMed using the keywords “mistreatment”, “obstetric violence”, “disrespect and abuse” and “dehumanised care”, as these all denote the concept of poor treatment of women in childbirth by health care providers. The search was limited to the period 2010–2020. The last search was carried out on 17th March 2021. The inclusion criteria comprised qualitative or quantitative empirical research characterising women’s experience of childbirth in health facilities, written in English, and limited to India.

Data extraction and analysis

The eligible articles went through a standardised data extraction process, and the researcher extracted the relevant data/information in an Excel sheet. A synthesis of evidence was conducted through thematic analysis, including coding the text line-by-line as a first step. Descriptive themes were then developed and analysed against the objective of the study.

Conceptual framework

Obstetric violence is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that has been analysed differently by different stakeholders who have used several terms to describe and explain it. Hence, there is no clear and agreed conceptual definition of obstetric violence. The report titled “Disrespectful and abusive treatment during childbirth in facilities” published by WHO in 2014, included the following behaviours as obstetric violence: “physical abuse, profound humiliation and verbal abuse, coercive or unconsented medical procedures (including sterilisation), lack of confidentiality, failure to get fully informed consent, refusal to give pain medication, gross violations of privacy, refusal of admission to health facilities, neglecting women during childbirth to suffer life-threatening, avoidable complications, and detention of women and their new-born in facilities after childbirth due to an inability to pay” (p. 1).11

The notion of obstetric violence first originated in Latin America and Spain due to activist movements aimed at humanising childbirth. In the early 1980s, the over-medicalisation of maternal care in Latin America culminated in a movement aimed at “humanising childbirth” in institutions. As a legal term, the notion of obstetric violence first originated in Venezuela in 2007, followed by Argentina in 2009 and Mexico in 2014, where perpetrators of obstetric violence are subjected to criminal charges.12 According to feminist philosopher Shabot, obstetric violence is different from other forms of medical violence because labouring and birthing bodies are not ill, diseased, or dysfunctional. Instead, the labouring body is usually “a healthy and powerful body” (p. 233).5

Although the conceptual work on obstetric violence by Shabot5 and Wolf13 is significant, they do not investigate power and violence as multifaceted and intersecting issues. Obstetric violence does not happen in a vacuum. The violence that exists in our health system has been normalised by our deep-rooted patriarchal and unequal society. Paul Farmer defines structural violence as “social arrangements that put individuals and populations in harm’s way. The arrangements are structural because they are embedded in the political and economic organisation of our social world; they are violent because they cause injury to people” (p. 1686).14 Hence, it is also important to study obstetric violence as structural violence and not merely at the individual level, in order to understand the organisational context that facilitates the emergence and sustenance of patterns of violent and abusive behaviours within healthcare facilities.

Findings

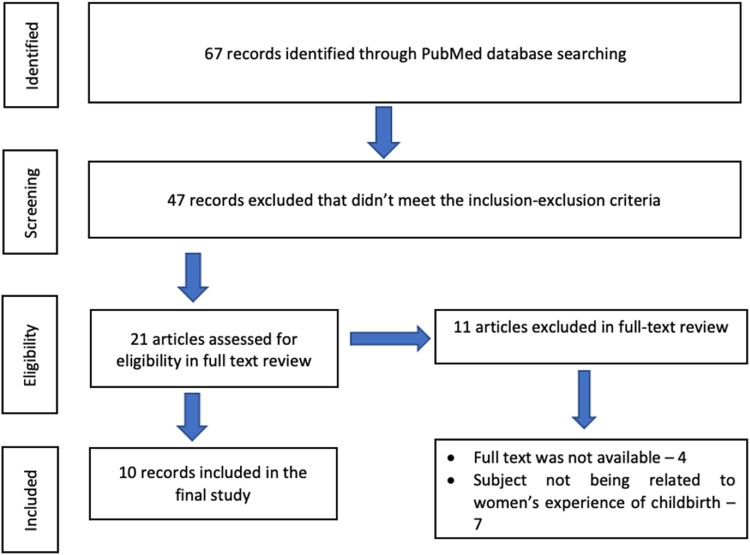

We identified 67 potentially relevant articles from the initial database search. When screening the abstracts, 47 articles were excluded from the review as they were not related to women’s childbirth experiences in healthcare facilities. Twenty-one (21) articles were finally retained for the full-text review. Of these, the full texts of four articles were not available, so they were removed from further analysis. After analysing the full texts for eligibility, 10 articles were ultimately included in the review, as listed in Table 1. Figure 1 presents the flow chart of the article selection process.

Table 1.

Studies included in the review

| Authors | Methodology | Subject area | Topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudhinaraset et al.8 | Mixed-method (Cross-sectional) | Slum Area (Uttar Pradesh) | Factors associated with women’s report of mistreatment, how it is perpetrated, its drivers and consequences |

| Diamond-Smith et al.15 | Quantitative method (Cross-sectional) | Slums of Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh) | Association between women’s empowerment and mistreatment during the time of childbirth |

| Chattopadhyay et al.1 | Qualitative method (Cross-sectional) | Community (Assam) | Women’s experience of obstetric violence during childbirth and associated factors |

| Raj et al.7 | Quantitative method (Cross-sectional) | Community (Women who delivered in Public Health Facilities) (Uttar Pradesh) | Associations between mistreatment during childbirth and maternal complications |

| Bhattacharya and Ravindran16 | Mixed-method (Cross-sectional) | Community (Uttar Pradesh) | Frequency and nature of disrespect and abuse experienced in healthcare facilities by women, and possible associations |

| Madhiwalla et al.17 | Qualitative method (Cross-sectional) | Government Hospitals (Mumbai) | Examined organisational context in order to understand disrespect and abuse |

| Morgan et al.18 | Qualitative method (Cross-sectional) | Government Hospitals (Bihar) | Barriers and facilitators to optimal obstetric care |

| Goli et al.19 | Quantitative method (Longitudinal study) | Community (Uttar Pradesh) | Investigates the prevalence of labour room violence and association between prevalence of obstetric violence and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents |

| Sharma et al.20 | Mixed-method (Cross-sectional) | Government & Private Hospitals (Uttar Pradesh) | Investigates the nature and context of mistreatment during labour and childbirth at public and private maternity facilities |

| Shrivastava and Sivakami12 | Integrative literature review | India | Collates and analyses the existing literature on obstetric violence in India |

Figure 1.

Process of article selection

Of the ten studies included in the review, three studies were based purely on quantitative methods and three purely on qualitative methods. Three studies used mixed methods, and one study was based on an integrative review of the literature. All the studies, except two, adopted a cross-sectional design.

The nature of obstetric violence

There is growing evidence of abusive and disrespectful treatment of women in health facilities during childbirth. However, there is no agreement to date on the range of behaviours that count as abuse and disrespect and how these may be categorised. The abusive and disrespectful treatment of women can occur at multiple levels, including interactions between women and service providers, as well as systemic failures at the health facility and health system levels. The study of Bohren et al.3 established a typology of the mistreatment of women during childbirth that includes seven dimensions. These dimensions are (i) physical abuse (slapping, tweaking, or pinching during delivery); (ii) verbal abuse (using harsh or rude language); (iii) sexual abuse; (iv) stigma and discrimination (based on socioeconomic conditions, age, ethnicity, or medical conditions); (v) incompetency in maintaining professional standards of care (mistreatment, abandonment, and neglect during childbirth); (vi) a poor rapport between women and providers (including ineffective or no communication at all, absence of supportive care, and loss of autonomy); and (vii) incompetency on the part of the health system (lack of the resources to maintain the privacy of women).3 The findings of the present study were accordingly categorised under these seven dimensions. Table 2 highlights the different forms of obstetric violence experienced by women as described in empirical studies from India.

Table 2.

Nature of obstetric violence in the Indian context

| Type of abuse | Characteristics | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse | – | [7,8,17] |

| Slapping, punching, beating or tying the women | [16,20] | |

| Sexual abuse | – | - |

| Verbal abuse | – | [7,8,20] |

| Shouting, scolding, yelling | [1,16,17] | |

| Stigma and discrimination | Discriminatory behaviours because of caste and class | [7,15,17,19] |

| Discriminatory behaviours because of religion | [19] | |

| Treated differently because of particular community or class | [7] | |

| Failure to meet professional standards of care | Request for bribe | [8,18,20] |

| Abandoned or ignored | [7,8,16] | |

| Unnecessary separation from baby | [8] | |

| Forcefully pushed abdomen during delivery | [7,17] | |

| Applied force to pull the baby | [7] | |

| Did not take consent prior to the treatment | [7,16] | |

| Lack of physical privacy | [16] | |

| Post-partum contraception | [17] | |

| Use of pain relief medication | [17] | |

| Episiotomy | [1,17,20] | |

| Fundal Pressure | [20] | |

| Poor rapport between women and providers | Lack of information | [7,8,16] |

| Threats to withhold treatment | [8,16] | |

| Choice of positions denied | [8] | |

| Companion not allowed | [8] | |

| Support from providers during the stay in a facility | [7] | |

| Health system conditions and constraints | High workload | [17] |

| Adverse working conditions | [17] | |

| Shortages and misallocation of resources | [17,18] | |

| Staffing shortage | [17] | |

| Unqualified birth attendants | [20] | |

| Hygiene in Health facilities | [20] |

Verbal abuse

Table 2 shows that verbal abuse such as shouting, scolding, and yelling is the most common form of abuse women experience in health facilities, followed by physical abuse. Sexist comments were also prevalent in public health services. One of the studies illustrates a nurse’s comment to a patient that “when you are with your husbands, you don’t shout, but you are shouting now. You will come again with another baby soon!”.20

Physical abuse

This may take many forms, from slapping the pregnant woman to striking and squeezing her thighs while bearing down (Table 2). A study of mistreatment during labour at public and private maternity hospitals in Uttar Pradesh found that physical violence (striking or pinching) towards pregnant women was more common in public as compared to private maternity hospitals.20

Stigma and discrimination

Discrimination toward women from lower castes, minorities, and socioeconomic backgrounds is also widespread in Indian healthcare facilities.7,8,19 According to most respondents, poverty was the most crucial predictor of who would be mistreated or assaulted. The quality of treatment at government hospitals was inadequate for the low-income patients, while those in the middle or upper socioeconomic classes often received better services and had fewer hurdles to receiving care in the public sector.8 A study of labour room violence demonstrated that women from Scheduled Castes (20.6%) and Other Backward Class (15.2%) had a higher prevalence of labour room violence as compared to women from upper castes or the general category (12.5%). The study also revealed that Muslim (18%) women are more likely to experience labour room violence than Hindu (16%) women.19

Failure to meet professional standards of care

The practice of asking for bribes was widespread, which is the case in most public health facilities. The nurses frequently demand money, claiming that they conducted the birth so well and that the child would have died if they had not.8 Negligence and ignorance of current good practice on the part of nurses, which were found to be one of the characteristics of women’s labour experiences, have been depicted in the results. Furthermore, use of force, lack of physical privacy, involuntary post-partum contraception, failure to seek the woman’s consent for clinical procedures, and routine and often unwarranted episiotomy were other common practices in health centres (Table 2).

Routine episiotomies constitute obstetric violence, and there is no medical evidence to support their regular use. Nevertheless, many Indian doctors routinely perform episiotomies without anaesthesia.1,20 In their research in two hospitals in Mumbai, Madhiwalla et al.10 identified an informal code in both institutions requiring women to accept tubal ligation after two births and IUD insertion after the first. The most common methods of putting pressure on women were refusing discharge, threatening not to perform the delivery, and barring her from visiting the hospital.17

Health system conditions and constraints

High workload, unfavourable working circumstances, resource scarcity, and misallocation, untrained birth attendants, and hygiene issues in health facilities were found as significant conditions and constraints contributing to the manifestation of obstetric violence (Table 2).

Poor rapport between women and providers

Not allowing a companion, lack of support from providers during the stay in the facility, and threats to withhold treatment are prevalent forms of disrespect in the studies included in the review (Table 2).

The research articles used in this present study showed no proof of sexual harassment of women by healthcare providers.

The organisational context that produces and reproduces dehumanising behaviour and actions

Obstetric violence and dehumanising conduct of childbirth exist not only due to encounters between care providers and women at an individual level. They also exist at the organisational level, where an abusive environment and culture within the health facility produces and sustains such behaviours. Under- and untrained staff,18,20 lack of necessary medicines and equipment,17,18 lack of infrastructure facilities,17 workload,17 hierarchy among staff,6,18 caste and class-based discrimination,7,8,19 and discrimination based on religion,19 create an abusive environment and culture within health facilities, resulting in dehumanising care to women during childbirth.

Staffing shortages and inadequate or untrained staff are major concerns that lead to longer wait times, negligent and poor-quality service. Due to understaffing, providers often feel overworked, too busy, and stretched, which leads to frustration and stress, resulting in dehumanising behaviour such as shouting, yelling, beating, and neglect. Furthermore, in the absence of required staff, health workers who do not have adequate experience or training are entrusted with clinical care and so they perform inadequate levels of treatment in the absence of competent supervision.17,18,20 Also, due to the lack of infrastructure facilities and resources, healthcare providers could not ensure privacy during vaginal and abdominal examinations.17

Furthermore, patriarchal cultures and organisational hierarchies foster undemocratic power relations between patients and providers. Due to the historical normalising of gender-based violence, women in general, and those of lower socioeconomic position in particular, have lower levels of assurance of adequate and quality treatment during childbirth.12

Discussion and conclusion

The present review explored the nature of obstetric violence and the organisational context that contributes to and sustains it. The review’s findings demonstrate that the most common form of obstetric violence is verbal abuse followed by physical abuse and other forms of dehumanising behaviour. The tendency of nurses to ask for bribes for conducting the delivery skilfully was shown to be quite widespread.8

It was also evident from the review’s findings that the public health system cannot provide quality health care to women who cannot afford the private health sector. Low-income women have no option but to use public facilities for birth. They expect abusive behaviour, and therefore do not think it is abnormal. Studies included in the review stated that women from lower caste and low-income family backgrounds are at higher risk of experiencing obstetric violence and dehumanising behaviours from care providers in public health facilities. Furthermore, one of the studies reveals abusive behaviour due to hatred towards a particular community. The study reported that labour room violence is found more towards Muslims than towards other communities.19 Therefore, it becomes essential to understand the intersectionality of obstetric violence and discrimination with caste, class, religion, and deep-rooted patriarchy. The generalised and normalised nature of obstetric violence manifests deep-rooted patriarchal notions of control over women. However, we must also view obstetric violence from the intersection of gender with other axes of societal hierarchies such as class and caste. Mistreatment of women during childbirth is not just a matter of poor quality of care, but it is also indicative of broader human rights violations.

The present study found several organisational and health system factors that make for an abusive atmosphere and culture within healthcare settings, contributing to obstetric violence. These included the shortage and misallocation of resources, shortage of staff, under- or untrained staff, lack of infrastructural facilities, caste, class, religion-based discrimination, and lack of necessary medicines and equipment. The study by Bohren et al.3 similarly finds that staffing constraints directly affect care provision and contribute to the health workers’ negative attitudes and low motivation. Additionally, due to a lack of infrastructure and resources, such as unavailability of curtains to separate women from other patients, healthcare practitioners are not in a position to provide privacy during vaginal examination. Inadequate medical supplies, such as medicine, gloves, equipment, and blood, create additional risk and stress in their profession.3 Furthermore, the hierarchical structure of the health system legitimises the control of health workers over women during childbirth. New and junior staff learn from the facility’s existing environment and culture, where senior staff practise obstetric violence and legitimise such behaviours.6

Our review has indicated the widespread and systemic nature of obstetric violence. The abusive environment in health facilities fosters fear about facility care among women, contributes to worsened health outcomes, and deters women from further utilisation of healthcare services. Therefore, along with expanding institutional deliveries and access to emergency obstetric care, measures should be taken to ensure dignified treatment during childbirth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Chattopadhyay S, Mishra A, Jacob S.. ‘Safe’, yet violent? Women's experiences with obstetric violence during hospital births in rural Northeast India. Cult Heal Sex. 2017, 10.1080/13691058.2017.1384572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halperin O, Sarid O, Cwikel J.. The influence of childbirth experiences on women’s postpartum traumatic stress symptoms: a comparison between Israeli Jewish and Arab women. Midwifery. 2015;31:625–632. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:1–32. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . (2017). Mistreatment of women during childbirth: a sad reality worldwide.

- 5.Shabot SC. Making loud bodies “feminine”: a feminist-phenomenological analysis of obstetric violence. Hum Stud. 2016;39:231–247. 10.1007/s10746-015-9369-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen G, Reddy B, Iyer A, et al. Addressing disrespect and abuse during childbirth in facilities. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:1–5. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1509970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj A, Dey A, Boyce S, et al. Associations between mistreatment by a provider during childbirth and maternal health complications in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:1821–1833. 10.1007/s10995-017-2298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudhinaraset M, Treleaven E, Melo J, et al. Women’s status and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh: a mixed methods study using cultural health capital theory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16, 10.1186/s12884-016-1124-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamid Z. A natural touch to birthing experience. Chennai: The Hindu; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baru R, Acharya A, Acharya S, et al. Inequities in access to health services in India: caste, class and region. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;45:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . (2015). The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth.

- 12.Shrivastava S, Sivakami M.. Evidence of “obstetric violence” in India: an integrative review. J Biosoc Sci. 2020;52:610–628. 10.1017/S0021932019000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf AB. Metaphysical violence and medicalized childbirth. Int J Appl Philos. 2013;27:101–111. 10.5840/ijap20132719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, et al. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2006;3:1686–1691. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond-Smith N, Treleaven E, Murthy N, et al. Women’s empowerment and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in facilities in Lucknow, India: results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:130–158. 10.1186/s12884-017-1501-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya S, Sundari Ravindran TK.. Silent voices: institutional disrespect and abuse during delivery among women of Varanasi district, Northern India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18, 10.1186/s12884-018-1970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madhiwalla N, Ghoshal R, Mavani P, et al. Identifying disrespect and abuse in organizational culture: a study of two hospitals in Mumbai, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:36–47. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1502021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan MC, Dyer J, Abril A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the provision of optimal obstetric and neonatal emergency care and to the implementation of simulation-enhanced mentorship in primary care facilities in Bihar, India: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18, 10.1186/s12884-018-2059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goli S, Ganguly D, Chakravorty S, et al. Labour room violence in Uttar Pradesh, India: evidence from a longitudinal study of pregnancy and childbirth. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028688, 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma G, Penn-Kekana L, Halder K, et al. An investigation into mistreatment of women during labour and childbirth in maternity care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India: A mixed methods study. Reprod. Health. 2019;16, 10.1186/s12978-019-0668-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]