Abstract

Objective

To investigate Chinese guardians’ willingness to vaccinate teenagers (WVT) against COVID-19, we conducted a national wide survey in 31 provinces in mainland China.

Methods

We involved 16133 guardians from 31 provinces in Chinese Mainland from August 6th to 9th, 2021. The question “Are you willing to vaccinate teenagers of COVID-19 vaccine?” was designed to capture WVT. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for potential factors of WVT were estimated using multiple logistic regression models.

Results

In total, 13327 (82.61%) of the respondents expressed positive WVT, 12.90% of the respondents were uncertain but inclined to vaccinate their teenagers. Meanwhile, 3.89% of the respondents were uncertain and inclined to reject, and 0.60% of the respondents rejected the vaccines. After adjusting for potential confounders, the married, total family income last year, reject to Categoly1 vaccines, access information about the COVID-19 vaccines from community workers, low COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy, guardian's vaccination behavior, and the importance of vaccinating teenagers were all independent factors that affected the guardians' likely to accept. Further, the current study found that lower trust in doctors and vaccine developers was associated with negative WVT. The reasons for negative WVT included teenagers’ young age and guardians’ worries on the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

Conclusion

This large-scale study assessed Chinese guardians’ WVT against COVID-19, as well as its potential influencing factors, which is useful for international and national decision-makers.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccines, Willingness, Guardians, Teenagers

1. Introduction

With the emergence of mutated 2019 Novel Coronaviruses that spreads faster and more contagious and adult vaccination rate increases, younger children are more likely to transmit the virus in certain environments, and have become important promoters of the spread of the COVID-19 (Heald-Sargent et al., 2020; Russell and Greenwood, 2021). According to the latest reports from the American Academy of Children, a total of nearly 4.8 million children had been confirmed with COVID-19 infection, which accounted for 14.8% of the total confirmed cases; at its worst, 200,000 children were diagnosed in the United States in one week (Children and COVID-19 2021a). Although children infected with COVID-19 were less likely to develop serious illness or death than adults, children who were younger or in poor health conditions were more likely to have serious multiple systemic inflammatory syndrome and persistent symptoms (Buonsenso et al., 2021; Felsenstein and Hedrich, 2020; Kest et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Nikolopoulou and Maltezou, 2021; Oualha et al., 2020; Stower, 2020). Vaccination is the most economical and effective means to prevent infectious diseases and block their transmission among teenagers (Abbas et al., 2020; Debellut et al., 2021).Therefore, timely completion of teenager vaccination is of great significance not only to control the source of infection, but also to cut off the route of transmission.

Since the outbreak of the epidemic, global scientists have been intensively involved in the development of the COVID-19 vaccines for teenagers. The clinical trials of the mRNA-1273 vaccine developed by Moderna for teenagers aged 12–17 indicated that no serious adverse events related to mRNA-1273 or placebo were noted and the geometric mean titer ratio of pseudovirus neutralizing antibody titers in adolescents relative to young adults was 1.08 (Ali et al., 2021). Pfizer also announced the details about phase Ⅲ of clinical trial among 2260 children aged 12–15 in the US, the results showed that no case of COVID-19 were observed in the vaccinated group compared with the placebo group, and the vaccine also elicited robust antibody responses and was well tolerated with side effects consistent with those observed in participants aged 16–25 (Mahase, 2021). In addition, Pfizer announced currently that a vaccine trial for children over 6 months to 11 years old has also been started (Mahase, 2021). Moreover, China's National Bio-Beijing Institute of Biological Products Co., Ltd. and Beijing Kexing Zhongwei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. have also fully demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines in the clinical trial results of people aged 3–17(The State Council joint prevention and control mechanism of August 27 2021,).

However, not only the efficacy and safety of vaccines but the guardians’ willingness will affect teenagers’ vaccination rate (Sallam 2021). Globally, guardians’ willingness to vaccinate their teenagers against COVID-19 was influenced by complex and multi-dimensional factors (Zhang et al., 2021). In New York, guardians’ gender, religion, safety, effectiveness of the vaccine and lack of need had an influence on the willingness to vaccinate their children (Teasdale et al., 2021b). In the United Kingdom, lower-income parents were likely rejecting vaccine for children because of vaccines’ safety and effectiveness (Bell et al., 2020). Australian parents vaccine hesitancy or refusal was associated with female, younger, having a lower level of education and socioeconomic status (Rhodes et al., 2021).In Italy, highest vaccine hesitancy rates were detected in female parents, ≤29 years old, with low educational level, and relying on information found in the web/social media (Montalti et al., 2021). Parents with low anxiety about COVID-19 infection, distrust in abroad vaccines, and lack of knowledge about the effectiveness of vaccines in Turkey were more likely to refuse vaccination (Yigit et al., 2021). Additionally, a survey of Chinese parents of children aged 3–6 showed parents who were female were often more willing to vaccinate their children if they followed up on COVID-19 vaccine-related information, believed in the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines (Wan et al., 2021). However, such information about guardians of teenagers aged 3–17 years is lacking in China in the context of available vaccines.

COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese teenagers plays an important role in global COVID-19 prevention and control, not only because China has the world's largest population of teenagers, but also because there is no empirical evidence of low risk of COVID-19 infection among Chinese teenagers. In current stage, China has started COVID-19 vaccination for teenagers aged 12 and above across the nation. 162.28 million doses of the teenagers aged 12–17 years old have been officially confirmed to be vaccinated to date (The State Council joint prevention and control mechanism of September 7 2021), and children aged 3–12 will soon be covered. In view of the fact that a substantial proportion of teenagers are still unvaccinated, therefore we conducted a large-scale survey in mainland China to obtain better understandings of vaccination willingness from guardians’ psychological level. Based on the assessment of guardian's willingness to vaccinate their teenagers, the current study will provide policy implications for increasing vaccination acceptance rate and optimizing the supply of COVID-19 vaccines in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

The teenagers in this study refer to minors over 3 years old and under 18 years old. Guardians are parents or grandparents of teenagers.

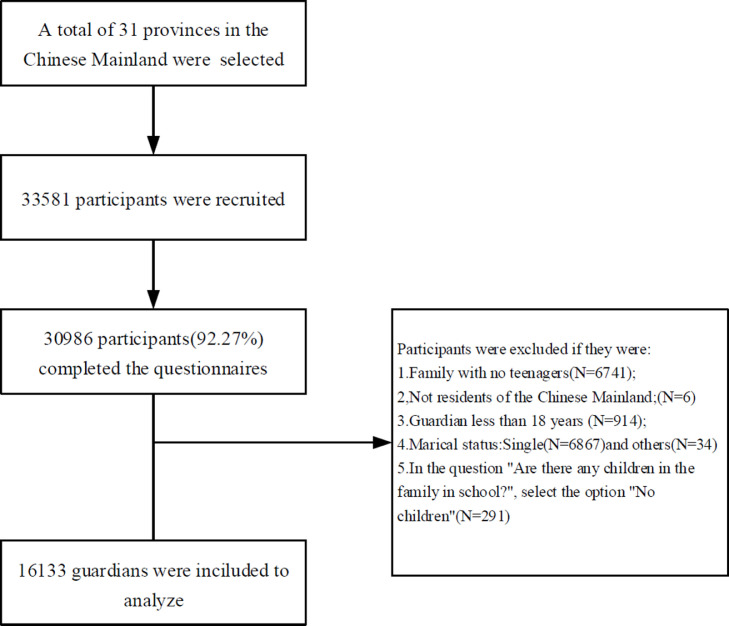

On July 10, 2021, we performed a preliminary online survey in Zhongmu County, Henan Province. We conducted a face-to-face interview with participants from a representative village and community obtained through a cluster sampling approach. we estimated the minimum sample size required for the formal survey to be 6123 participants, which was based on a prevalence of likely rejecting COVID-19 vaccination of 15% in a preliminary online survey, an allowable error of 1%, a 95% confidence level, a missing questionnaire rate of 20% and an anticipated design effect of two. A subsequent national cross-sectional online survey using a snowball sampling method among Chinese adults (≥18 years old) was conducted from August 6th to 9th, 2021 via a market research company. The invited respondents were unaware of the topic before their tentative consent to complete the survey. The flowchart of participant selection was shown in Fig. 1 . This study was approved by the Life Science Ethics Review Committee of Zhengzhou University. All study participants consented for participation in this study.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants.

2.2. Data collection

A standard questionnaire was developed to assess the respondents from five aspects: (1) Demographic; (2) Awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) Awareness of the vaccines; (4) Healthcare system; (5) WVT.

2.2.1. Demographic

Basic information of the guardians, including gender, age, marital status, education level, total family income last year, the number of teenagers, and whether there are children in school.

2.2.2. Awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic

It consists of the guardians’ perception of the risk of COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (higher scores indicate greater endorsement of conspiracy statements).

2.2.3. Awareness of vaccines

Including the safety and effectiveness of general vaccines, the channel of accessing information of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as rejection of Category 1 vaccine, guardians’ vaccination behavior, the importance of vaccinating teenagers, and endorsement of COVID-19 vaccines conspiracy belief (higher scores indicate greater endorsement of conspiracy statements).

2.2.4. Trust in health care system

It includes the degree of trust in doctors and vaccine developers. (higher scores indicate higher trust in doctors and vaccine developers).

2.2.5. WVT

The question “Are you willing to vaccinate teenagers of COVID-19 vaccine?” was designed to capture WVT. The options are “Yes, definitely”, “Uncertain but inclined to yes”, “Uncertain but inclined to no”, “No, definitely not”. Answering “Yes, definitely” and “Uncertain but inclined to yes” will be asked about the main reason for being willing to vaccinate, and those who answered “Uncertain but inclined to no” and “No, definitely not” will also be asked about the main reason for not willing to vaccinate.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The missing values of the two variables (age, and total household income last year) accounted for less than 5%, so they were filled in with the median. The results of the normality test showed that continuous variables didn't conform to normal distribution. Therefore, for the convenience of comparative analysis, total family income last year and scale scores were converted into ordered data (Levels 1–4) according to quartiles, and WVT was dichotomized into “likely to accept” (those that answered Yes, definitely or Uncertain but inclined to yes) and “likely to reject” (those that answered No, definitely not or Uncertain but inclined to no) in univariate analyses and binary logistic regression analysis. The collinearity test was carried out to assess the correlation between independent variables using a variance inflation factor (VIF<4), and no collinearity was detected. We ran univariate analyses followed by binary logistic regression analysis, including all factors showing significance (p < 0.05), to determine factors associated with WVT. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and p-values were calculated for each independent variable. The model fit of binary logistic regression analysis was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the differences between groups. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics and willingness of COVID-19 vaccination among study guardians

This study finally included 16,133 guardians. A summary of the demographic, awareness of COVID-19 pandemic, awareness of the vaccines, trust in health care system, and WVT of all study participants was provided in Table 1 . In all, 13,327 (82.61%) of the respondents expressed positive WVT, 12.90% of the respondents were uncertain but inclined to vaccinate their teenagers. Meanwhile, 3.89% of the respondents were uncertain and inclined to reject, and 0.60% of the respondents rejected the vaccines. Among the guardians participating in the survey, many guardians were very worried/worried about the safety (32.23%) and effectiveness (33.86%) of general vaccines. It is worth noting that guardians who have been vaccinated accounted for the vast majority (78.39%). Additionally, those aged 18–29 years old, don't plan to vaccinate themselves, low trust in doctors, vaccines and their developers had the highest percentage of definite refusal (1.22%, 15.07%, 1.32%, 1.19%, 1.52%, respectively). Guardians who accessed information about vaccines from community workers, had high trust in doctors, vaccine and their developers accounted for the highest percentage of definite acceptance (90.14%, 95.70%, 92.30%, 95.35%, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics and willingness of COVID-19 vaccination among study guardians.

| Variable | Total sample n (%) | Likely to accept | Likely to reject | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, definitely | Unsure but inclined to yes | Unsure but inclined to no | No, definitely not | ||

| All participants | 16133 (100.00) | 13327 (82.61) | 2081 (12.90) | 628 (3.89) | 97 (0.60) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 7404 (45.89) | 5836 (78.82) | 1104 (14.91) | 398 (5.38) | 66 (0.89) |

| Female | 8729 (54.11) | 7491 (85.82) | 977 (11.19) | 230 (2.63) | 31 (0.36) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

| 18–29 | 2951 (18.29) | 2135 (72.35) | 529 (17.93) | 251 (8.51) | 36 (1.22) |

| 30–39 | 9423 (58.41) | 7895 (83.78) | 1190 (12.63) | 290 (3.08) | 48 (0.51) |

| 40–49 | 2866 (17.76) | 2551 (89.01) | 249 (8.69) | 56 (1.95) | 10 (0.35) |

| 50–59 | 734 (4.55) | 622 (84.74) | 91 (12.40) | 18 (2.45) | 3 (0.41) |

| 60- | 159 (0.99) | 124 (77.99) | 22 (13.84) | 13 (8.18) | 0 (0.00) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 15388 (95.38) | 13012 (84.56) | 1826 (11.87) | 475 (3.09) | 75 (0.49) |

| Others | 745 (4.62) | 315 (42.28) | 255 (34.23) | 153 (20.54) | 22 (2.95) |

| Education | |||||

| Below high school | 2560 (15.87) | 1736 (67.81) | 539 (21.05) | 247 (9.65) | 38 (1.48) |

| High school graduate | 5272 (32.68) | 4554 (86.38) | 542 (10.28) | 155 (2.94) | 21 (0.40) |

| University graduate | 8301 (51.45) | 7037 (84.77) | 1000 (12.05) | 226 (2.72) | 38 (0.46) |

| Total household income last year (Ten thousand) | |||||

| ≤ 8 | 4272 (26.48) | 3426 (80.20) | 597 (13.97) | 214 (5.01) | 35 (0.82) |

| 9–14 | 4077 (25.27) | 3446 (84.52) | 493 (12.09) | 105 (2.58) | 33 (0.81) |

| 15–20 | 3954 (24.51) | 3355 (84.85) | 468 (11.84) | 117 (2.96) | 14 (0.35) |

| >20 | 3830 (23.74) | 3100 (80.94) | 523 (13.66) | 192 (5.01) | 15 (0.39) |

| Number of teenagers | |||||

| 1 | 11066 (68.59) | 9099 (82.22) | 1470 (13.28) | 434 (3.92) | 63 (0.57) |

| 2 | 4314 (26.74) | 3557 (82.45) | 551 (12.77) | 180 (4.17) | 26 (0.60) |

| ≥3 | 753 (4.67) | 671 (89.11) | 60 (7.97) | 14 (1.86) | 8 (1.06) |

| Children in school | |||||

| Yes | 12867 (79.76) | 10771 (83.71) | 1592 (12.37) | 439 (3.41) | 65 (0.51) |

| No | 3266 (20.24) | 2556 (78.26) | 489 (14.97) | 189 (5.79) | 32 (0.98) |

| Awareness of COVID-19 pandemic | |||||

| Risk of COVID-19 infection | |||||

| Very high/High | 2721 (16.87) | 1926 (70.78) | 572 (21.02) | 196 (7.20) | 27 (0.99) |

| Medium | 2482 (15.38) | 1806 (72.76) | 469 (18.90) | 191 (7.70) | 16 (0.64) |

| Low/No | 10529 (65.26) | 9285 (88.19) | 976 (9.27) | 220 (2.09) | 48 (0.46) |

| Not sure | 401 (2.49) | 310 (77.31) | 64 (15.96) | 21 (5.24) | 6 (1.50) |

| COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs | |||||

| Level 1 | 3762 (23.32) | 3430 (91.17) | 275 (7.31) | 42 (1.12) | 15 (0.40) |

| Level 2 | 3635 (22.53) | 3284 (90.34) | 288 (7.92) | 56 (1.54) | 7 (0.19) |

| Level 3 | 4356 (27.00) | 3427 (78.67) | 652 (14.97) | 236 (5.42) | 41 (0.94) |

| Level 4 | 4380 (27.15) | 3186 (72.74) | 866 (19.77) | 294 (6.71) | 34 (0.78) |

| Vaccine Awareness | |||||

| Safety of general vaccines | |||||

| Very worried/Worried | 5200 (32.23) | 3820 (73.46) | 994 (19.12) | 342 (6.58) | 44 (0.85) |

| General | 2868 (17.78) | 2135 (74.44) | 536 (18.69) | 164 (5.72) | 33 (1.15) |

| Not worried/Completely not worried | 8065 (49.99) | 7372 (91.41) | 551 (6.83) | 122 (1.51) | 20 (0.25) |

| Effectiveness of general vaccines | |||||

| Very worried/Worried | 5463 (33.86) | 4146 (75.89) | 974 (17.83) | 296 (5.42) | 47 (0.86) |

| General | 2923 (18.12) | 2100 (71.84) | 587 (20.08) | 210 (7.18) | 26 (0.89) |

| Not worried/Completely not worried | 7747 (48.02) | 7081 (91.40) | 520 (6.71) | 122 (1.57) | 24 (0.31) |

| Reject to vaccinate Category1 vaccines | |||||

| Yes | 4478 (27.76) | 3501 (78.18) | 748 (16.70) | 212 (4.73) | 17 (0.38) |

| No/Not sure | 11655 (72.24) | 9826 (84.31) | 11333 (11.44) | 416 (3.57) | 80 (0.69) |

| Channel of vaccine information | |||||

| Community workers | 5132 (31.81) | 4626 (90.14) | 397 (7.74) | 93 (1.81) | 16 (0.31) |

| Internet | 7859 (48.71) | 6412 (81.59) | 1105 (14.06) | 298 (3.79) | 44 (0.56) |

| Others | 3142 (19.48) | 2289 (72.85) | 579 (18.43) | 237 (7.54) | 37 (1.18) |

| Guardians' vaccination behavior | |||||

| Has been vaccinated | 12647 (78.39) | 11443 (90.48) | 1007 (7.96) | 164 (1.30) | 33 (0.26) |

| Being vaccinated | 1853 (11.49) | 1156 (62.39) | 510 (27.52) | 172 (9.28) | 15 (0.81) |

| Ready to vaccinate | 1234 (7.65) | 602 (48.78) | 446 (36.14) | 165 (13.37) | 21 (1.70) |

| Not sure whether to vaccinate | 326 (2.02) | 101 (30.98) | 98 (30.06) | 110 (33.74) | 17 (5.21) |

| Don't plan to vaccinate | 73 (0.45) | 25 (34.25) | 20 (27.40) | 17 (23.29) | 11 (15.07) |

| Importance of vaccinating teenager | |||||

| Very important/Important | 15186 (94.13) | 13138 (86.51) | 1683 (11.08) | 329 (2.17) | 36 (0.24) |

| Not sure | 733 (4.54) | 153 (20.87) | 336 (45.84) | 210 (28.65) | 34 (4.64) |

| Not important/Not important at all | 214 (1.33) | 36 (16.82) | 62 (28.97) | 89 (41.59) | 27 (12.62) |

| Vaccine conspiracy beliefs | |||||

| Level 1 | 3701 (22.94) | 3416 (92.30) | 244 (6.59) | 27 (0.73) | 14 (0.38) |

| Level 2 | 4029 (24.97) | 3706 (91.98) | 260 (6.45) | 52 (1.29) | 11 (0.27) |

| Level 3 | 4270 (26.47) | 3518 (82.39) | 564 (13.21) | 165 (3.86) | 23 (0.54) |

| Level 4 | 4133 (25.62) | 2687 (65.01) | 1013 (24.51) | 384 (9.29) | 49 (1.19) |

| Trust in health care system | |||||

| Trust in doctors | |||||

| Level 1 | 3706 (22.97) | 2562 (69.13) | 774 (20.89) | 321 (8.66) | 49 (1.32) |

| Level 2 | 3985 (24.70) | 2879 (72.25) | 810 (20.33) | 256 (6.42) | 40 (1.00) |

| Level 3 | 4068 (25.22) | 3700 (90.95) | 330 (8.11) | 33 (0.81) | 5 (0.12) |

| Level 4 | 4374 (27.11) | 4186 (95.70) | 167 (3.82) | 18 (0.41) | 3 (0.07) |

| Trust in vaccine developers | |||||

| Level 1 | 3880 (24.05) | 2672 (68.87) | 818 (21.08) | 331 (8.53) | 59 (1.52) |

| Level 2 | 3636 (22.54) | 2688 (73.93) | 703 (19.33) | 222 (6.11) | 23 (0.63) |

| Level 3 | 4294 (26.62) | 3845 (89.54) | 377 (8.78) | 60 (1.40) | 12 (0.28) |

| Level 4 | 4323 (26.80) | 4122 (95.35) | 183 (4.23) | 15 (0.35) | 3 (0.07) |

Data are number (percentage). COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs score (Level 1:0–7, Level 2: 8–13, Level 3: 14–21, Level 4: 22–35). Vaccine conspiracy beliefs score (Level 1:0–7, Level 2: 8–12, Level 3: 13–18, Level 4: 19–35). Trust in doctors score (Level 1:9–28, Level 2: 29–34, Level 3: 35–39, Level 4: 40–45). Trust in vaccine developers score (Level 1:5–16, Level 2: 17–20, Level 3: 21–24, Level 4: 25).

3.2. Factors associated with guardians’ WVT

Through univariate analysis, we found that except for the number of teenagers, the others were statistically significantly correlated to the WVT. In the binary logistic regression model among all study participants, the married, total family income last year, reject to Categoly1 vaccines, access information about the COVID-19 vaccines from community workers, low COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy, guardian's vaccination behavior, and the importance of vaccinating teenagers were all independent factors that affected the guardians' likely to accept. It is worth noting that worries about the safety of general vaccines (OR=1.38,95%CI 1.03–1.83), low trust in doctors (OR=2.60,95%CI 1.48–4.57) and vaccine developers (OR=2.63,95%CI 1.41–4.91) were factors influencing the likely to reject vaccination (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Factors associated with guardians’ WVT.

| Variable | Unadjusted OR 95%CI | P value | Adjusted OR 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2.17(1.86–2.53) | <0.001 | 1.16(0.96–1.39) | 0.121 |

| Female | Reference | |||

| Age (Years) | <0.001 | |||

| 18–29 | 1.21(0.68–2.16) | 0.96(0.46–1.98) | 0.904 | |

| 30–39 | 0.42(0.23–0.74) | 0.82(0.40–1.71) | 0.600 | |

| 40–49 | 0.26(0.14–0.49) | 0.58(0.27–1.24) | 0.159 | |

| 50–59 | 0.33(0.16–0.68) | 0.51(0.21–1.20) | 0.124 | |

| 60- | Reference | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 0.12(0.10–0.15) | <0.001 | 0.68(0.52–0.88) | 0.003 |

| Others | Reference | |||

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Below high school | 3.81(3.21–4.54) | 1.13(0.89–1.43) | 0.326 | |

| High school graduate | 1.05(0.87–1.28) | 0.83(0.66–1.04) | 0.108 | |

| University graduate | Reference | |||

| Total household income last year | ||||

| (Ten thousand) | <0.001 | |||

| ≤ 8 | 1.08(0.90–1.31) | 0.84(0.67–1.07) | 0.159 | |

| 9–14 | 0.61(0.49–0.76) | 0.75(0.58–0.97) | 0.028 | |

| 15–20 | 0.60(0.48–0.75) | 0.93(0.72–1.21) | 0.607 | |

| >20 | Reference | |||

| Number of teenagers | 0.080 | |||

| 1 | 1.56(1.01–2.41) | - | - | |

| 2 | 1.67(1.07–2.60) | - | - | |

| ≥3 | Reference | |||

| Children in school | ||||

| Yes | 0.56(0.48–0.66) | <0.001 | 0.98(0.79–1.21) | 0.841 |

| No | Reference | |||

| Awareness of COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

| Risk of COVID-19 infection | <0.001 | |||

| Very high/High | 1.24(0.82–1.87) | 1.24(0.73–2.10) | 0.428 | |

| Medium | 1.26(0.83–1.91) | 1.29(0.76–2.17) | 0.347 | |

| Low/No | 0.36(0.24–0.54) | 1.02(0.61–1.69) | 0.954 | |

| Not sure | Reference | |||

| COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs | <0.001 | |||

| Level 1 | 0.19(0.14–0.25) | 1.72(1.11–2.65) | 0.014 | |

| Level 2 | 0.22(0.17–0.29) | 1.03(0.71–1.48) | 0.891 | |

| Level 3 | 0.84(0.71–0.99) | 1.23(0.99–1.54) | 0.063 | |

| Level 4 | Reference | |||

| Vaccine Awareness | ||||

| Safety of general vaccines | <0.001 | |||

| Very worried/Worried | 4.47(3.68–5.44) | 1.38(1.03–1.83) | 0.029 | |

| General | 4.12(3.30–5.13) | 1.41(1.06–1.88) | 0.019 | |

| Not worried/Completely not worried | Reference | |||

| Effectiveness of general vaccines | <0.001 | |||

| Very worried/Worried | 3.49(2.86–4.25) | 1.01(0.76–1.34) | 0.938 | |

| General | 4.57(3.70–5.65) | 1.12(0.85–1.49) | 0.418 | |

| Not worried/Completely not worried | Reference | |||

| Reject to vaccinate Category 1 vaccines | ||||

| Yes | 1.21(1.03–1.42) | 0.019 | 0.53(0.43–0.65) | 0.000 |

| No/Not sure | Reference | |||

| Channel of vaccine information | <0.001 | |||

| Community workers | 0.23(0.18–0.28) | 0.67(0.51–0.88) | 0.003 | |

| Internet | 0.48(0.40–0.56) | 0.89(0.73–1.09) | 0.272 | |

| Others | Reference | |||

| Guardians' vaccination behavior | <0.001 | |||

| Has been vaccinated | 0.03(0.02–0.04) | 0.17(0.09–0.31) | 0.000 | |

| Being vaccinated | 0.18(0.11–0.30) | 0.38(0.21–0.69) | 0.001 | |

| Ready to vaccinate | 0.29(0.17–0.47) | 0.43(0.24–0.79) | 0.007 | |

| Not sure whether to vaccinate | 1.03(0.61–1.73) | 1.52(0.81–2.87) | 0.196 | |

| Don't plan to vaccinate | Reference | |||

| Importance of vaccinating teenager | <0.001 | |||

| Very important/Important | 0.02(0.02–0.03) | 0.08(0.06–0.12) | 0.000 | |

| Not sure | 0.42(0.31–0.57) | 0.41(0.29–0.59) | 0.000 | |

| Not important/Not important at all | Reference | |||

| Vaccine conspiracy beliefs | <0.001 | |||

| Level 1 | 0.10(0.07–0.13) | 0.35(0.22–0.57) | 0.000 | |

| Level 2 | 0.14(0.10–0.18) | 0.46(0.32–0.67) | 0.000 | |

| Level 3 | 0.39(0.33–0.47) | 0.77(0.60–0.97) | 0.027 | |

| Level 4 | Reference | |||

| Trust in health care system | ||||

| Trust in doctors | <0.001 | |||

| Level 1 | 22.99(14.78–35.77) | 2.48(1.37–4.50) | 0.003 | |

| Level 2 | 16.63(10.66–25.95) | 2.60(1.48–4.57) | 0.001 | |

| Level 3 | 1.95(1.15–3.34) | 1.04(0.58–1.88) | 0.893 | |

| Level 4 | Reference | |||

| Trust in vaccine developers | <0.001 | |||

| Level 1 | 26.73(16.63–42.96) | 2.63(1.41–4.91) | 0.002 | |

| Level 2 | 17.28(10.68–27.95) | 2.26(1.23–4.15) | 0.009 | |

| Level 3 | 4.08(2.43–6.85) | 1.81(1.00–3.28) | 0.049 | |

| Level 4 | Reference |

Hosmer-Lemeshow test, chi-square:8.288, p-value:0.406.

COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs score (Level 1:0–7, Level 2: 8–13, Level 3: 14–21, Level 4: 22–35). Vaccine conspiracy beliefs score (Level 1:0–7, Level 2: 8–12, Level 3: 13–18, Level 4: 19–35). Trust in doctors score (Level 1:9–28, Level 2: 29–34, Level 3: 35–39, Level 4: 40–45). Trust in vaccine developers score (Level 1:5–16, Level 2: 17–20, Level 3: 21–24, Level 4: 25).

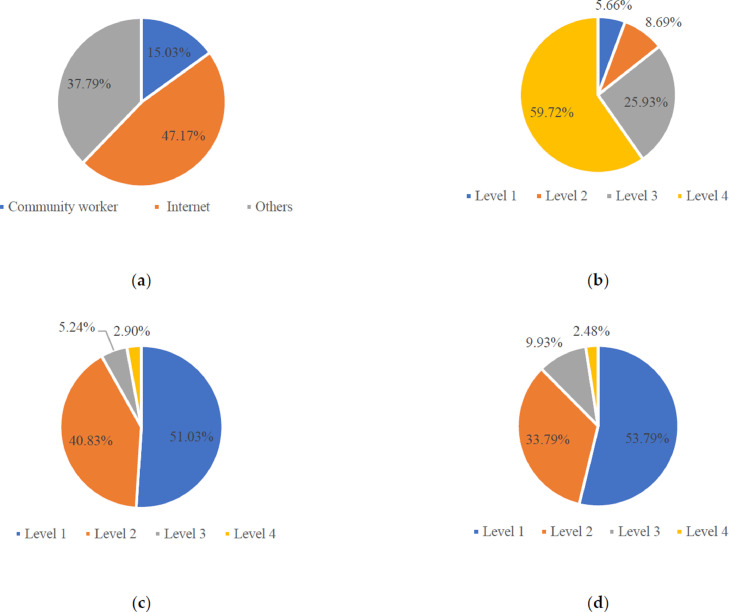

The following variables have statistically significant in the composition of guardians who were likely to accept and reject (all p < 0.001). Fig. 2 shows that among the guardians who were likely to reject vaccination (n = 725), 47.17% accessed vaccine information from the Internet, while only 15.03% accessed information from community workers. The vast majority of guardians (59.72%) were highly skeptical about the COVID-19 vaccine. Regarding the level of trust in the health care system, more than half of the guardians had low trust in doctors (51.03%) and vaccine developers (53.79%).

Fig. 2.

The relationship between the channel of vaccine information (a), COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy (b), trust in doctors (c), and trust in vaccine developers (d) and likely to reject vaccination(n = 725).

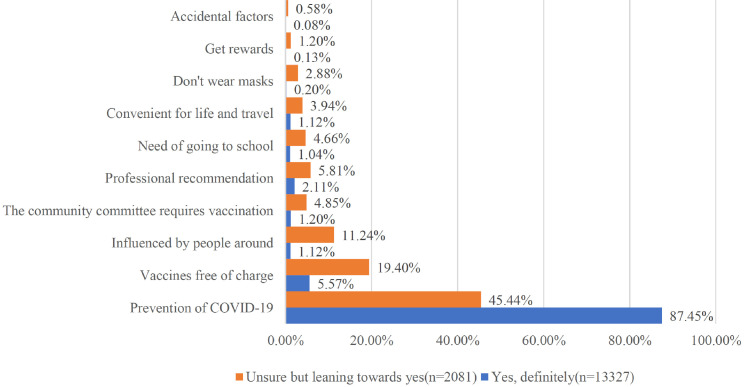

3.3. The reasons for guardians' WVT

In detail, the analysis found that the main reasons why guardians choose to vaccinate were prevention of COVID-19 (87.45%) and vaccines free of charge (5.57%). The main reasons for uncertain but inclined vaccination were prevention of COVID-19 (45.44%) and vaccines free of charge (19.40%) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Reasons of guardians likely to vaccinate teenagers.

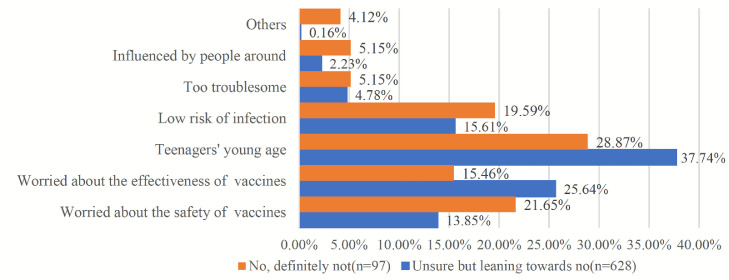

On the other hand, the unwillingness to vaccinate was mainly because of teenagers’ young age (28.87%), they worried about the safety of vaccines (21.65%) and believed that the risk of infection was low (19.59%). The primary reason for being uncertain but inclined not to vaccinate was teenagers’ young age (37.74%), followed by concerns about the effectiveness of vaccines (25.64%) and the belief that the risk of infection was low (15.61%) (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Reasons of guardians likely to reject to vaccinate teenagers.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the WVT in a large sample of 31 provinces of mainland China. Our findings indicated that most guardians clearly expressed their willingness (82.61%) or uncertain but inclined to (12.90%) vaccinate teenagers with the COVID-19 vaccines. Comparing with other studies (AlHajri et al., 2021; Bell et al., 2020; Montalti et al., 2021; Teasdale et al., 2021a; Wan et al., 2021) (48.2% in the United Kingdom, 49.4% in the United States, 60.4% in Italy, 44.2% in Kuwait, and 86.75% in China for 3–6 -years-old), we found that guardians in our study had higher WVT. In addition to the reason for the study location, it may be because the domestic adult vaccination rate was relatively high (over80%) (Lin et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). Parents’ attitudes towards themselves and their children’s vaccination were very consistent, those who were willing to vaccinate themselves were also more willing to vaccinate teenagers (Teasdale et al., 2021a,2021b). 78.39% of the guardians in this study have been vaccinated. Additionally, it should be noted that although teenagers can be vaccinated only with the consent of their guardians, they may also be affected by teachers or schools, but further research is needed.

Consistent with other studies (Teasdale et al., 2021a; Zhang et al., 2021), this article found that gender was not statistically significant with vaccination. On the other hand, many studies (Khubchandani et al., 2021; Montalti et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2021; Teasdale et al., 2021a) showed that parents with low education were more inclined not to vaccinate. In our study, education level was not statistically significant in binary logistic regression.

Different from existing studies (Montalti et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021), our results indicated that the guardian's age was not an influencing factor for vaccination. But in univariate analysis, we found that age was statistically significant. Furthermore, similar to other studies (Akhmetzhanova et al., 2020; Montalti et al., 2021), the channels to access vaccines information affected parents' willingness to vaccination. Supplementary Materials Table 1 analyzed the differences of different age groups accessing vaccines information (p < 0.001). The results showed that although all age groups mainly accessed information from the Internet, the proportion of guardians aged 18–29 was the highest. Moreover, the proportion of guardians who accessed information from community workers increased with age, while accessed information via the Internet decreased. Whereas only access information from community workers was statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounding factors. To improve the guardians' correct vaccination awareness, increasing the promotion of vaccine-related information through community workers may play a critical role. The Internet and other forms of media should serve as a link between vaccination services and guardians, they should effectively identify vaccine information transmitted by the Internet and other media, and eliminate any misleading information about vaccines.

The reason why guardians chose to be willing and uncertain but inclined to vaccinate was mainly to prevent the COVID-19 virus. This was consistent with the results of previous studies conducted on parents of children aged 3–6 (Bell et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2021). In line with other studies (Bell et al., 2020; Rhodes et al., 2021; Teasdale et al., 2021a, 2021b; Wan et al., 2021), concerns about vaccines’ safety and effectiveness and the perception that teenagers were at low risk of infection were also reasons for the tendency to reject in our study. These may be explained by the following reasons: Firstly, when a newly developed vaccine is facing society, it will cause residents to pay attention to its safety and effectiveness. And unlike general vaccines, the research process of the COVID-19 vaccines was more quickly, this will inevitably cause the public to worry about the safety problems caused by rushing to apply the vaccines to the actual situation without sufficient evidence to prove the safety (Bell et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021). Secondly, it may be due to that the reports of adverse events of general vaccines for children in China made the public lose confidence in vaccines (Han et al., 2019). Additionally, the public's trust in vaccine developers has decreased significantly due to recent vaccination-related adverse events (Du et al., 2020). In this survey, 32.23% of the guardians expressed their worries about the safety of general vaccines, more than half of the guardians (53.79%) had low trust in vaccine developers. In essence, willingness to vaccinate is based on trust. In our study, there is a considerable link between vaccine developers' distrust and likely to reject the COVID-10 vaccine. Notably, low trust in the vaccines was also an independent factor of the tendency to reject vaccination, which was consistent with the results of existing research (Holroyd et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2021).To build faith in vaccines and their developers, do a good job of monitoring the adverse reactions of vaccines in the population, and promptly publish information to prevent guardians from having inappropriate cognition. Meanwhile, vaccine developers and the government also should timely announce the relevant information about vaccines, such as the timeline and strict standards of vaccines development and relevant results of safety trials, through more authoritative channels to enhance the public's trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines and developers (Xu et al., 2021).Equally, for instilling guardians’ confidence in vaccination programs, the government should communicate clearly and consistently with guardians about vaccination, key measures that should also be considered include assisting guardians in obtaining a correct understanding in terms of x0027 teenagers' vaccination through education.

This is a large-scale study to assess the guardians’ WVT against COVID-19 in a sample of Chinese guardians. However, there are several limitations. One of the major limitations of the current study is that it relies on self-reports of willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccination, and we were unable to develop a standard for validation due to the lack of a universal scale to assess the willingness to vaccinate in China. Due to the fact an accurate assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance can serve as an important basis for vaccine development and production, as well as the estimation of market demand, the development of a global scale for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance assessment will become one of the important directions of future research. Another study's shortcomings include its cross-sectional design, which precluded the establishment of a cause-and-effect link. Finally, although we used data from a large sample of the population from 31 provinces, due to the epidemic, we were forced to collect data via online questionnaires utilizing the snowball sampling approach. Therefore, these research findings may differ from those estimated using probability sampling. In addition, the influence of socioeconomic level on COVID-19 vaccination willingness observed in this study may not apply to persons without Internet access.

5. Conclusion

Despite the limitations, Chinese guardians’ WVT was positive in general. Guardians' low trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, doctors, and vaccine developers was the main obstacle to vaccination acceptance. Typically, guardians considering their teenagers as too young are more likely to refuse the vaccination. Emphasis should be placed on improving trust in doctor and vaccine developers, assisting guardians in obtaining a correct understanding of teenagers’ vaccination and spreading reliable vaccines information via the Internet and other media.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jian Wu: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. Lipei Zhao: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. Meiyun Wang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Jianqin Gu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Wei Wei: Data curation. Quanman Li: Investigation, Software. Mingze Ma: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Zihan Mu: Investigation, Software. Yudong Miao: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (number 21BGL222); the Collaborative Innovation Key Project of Zhengzhou (number 20XTZX05015); Zhengzhou University 2020 Key Project of Discipline Construction (number XKZDQY202007); 2021 Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province (number YJS2021KC07); Performance evaluation of new basic public health service projects in Henan Province (number 2020130B)

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Abbas K., Procter S.R., van Zandvoort K., et al. Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit-risk analysis of health benefits versus excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(10):e1264–e1272. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30308-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmetzhanova Z., Sazonov V., Riethmacher D., et al. Vaccine adherence: the rate of hesitancy toward childhood immunization in Kazakhstan. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2020;19(6):579–584. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1775080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Hajri B., Alenezi D., Alfouzan H., et al. Willingness of parents to vaccinate their children against influenza and the novel coronavirus disease-2019. J. Pediatr. 2021;231:298–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali K., Berman G., Zhou H., et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S., Clarke R., Mounier-Jack S., et al. Parents' and guardians' views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38(49):7789–7798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonsenso D., Munblit D., De Rose C., et al. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(7):2208–2211. doi: 10.1111/apa.15870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children and COVID-19: 2021 State data report a joint report from the American academy of pediatrics and the children's hospital association.

- Debellut F., Clark A., Pecenka C., et al. Evaluating the potential economic and health impact of rotavirus vaccination in 63 middle-income countries not eligible for Gavi funding: a modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9(7):e942–e956. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00167-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F., Chantler T., Francis M.R., et al. The determinants of vaccine hesitancy in China: a cross-sectional study following the Changchun Changsheng vaccine incident. Vaccine. 2020;38(47):7464–7471. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein S., Hedrich C.M. SARS-CoV-2 infections in children and young people. Clin. Immunol. 2020;220 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Wang S., Wan Y., et al. Has the public lost confidence in vaccines because of a vaccine scandal in China. Vaccine. 2019;37(36):5270–5275. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald-Sargent T., Muller W.J., Zheng X., et al. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):902–903. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd T.A., Howa A.C., Delamater P.L., et al. Parental vaccine attitudes, beliefs, and practices: initial evidence in California after a vaccine policy change. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021;17(6):1675–1680. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1839293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kest H., Kaushik A., DeBruin W., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8875987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., et al. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J. Commun. Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L., Whitaker M., O'Halloran A., et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of children aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 14 states. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69(32):1081–1088. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e3. March 1-July 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Hu Z., Zhao Q., et al. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Luo L., Xie F., et al. Factors associated with the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine from adult subjects in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1899732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase E. COVID-19: Pfizer reports 100% vaccine efficacy in children aged 12 to 15. BMJ. 2021;373:n881. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalti M., Rallo F., Guaraldi F., et al. Would parents get their children vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2? Rate and predictors of vaccine hesitancy according to a survey over 5000 families from Bologna, Italy. Vaccines. 2021;9(4) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040366. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou G.B., Maltezou H.C. COVID-19 in children: where do we stand? Arch. Med. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oualha M., Bendavid M., Berteloot L., et al. Severe and fatal forms of COVID-19 in children. Arch. Pediatr. 2020;27(5):235–238. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes A., Hoq M., Measey M.A., et al. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21(5):e110. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell F.M., Greenwood B. Who should be prioritised for COVID-19 vaccination? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(5):1317–1321. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1827882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stower H. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of children with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26(4):465. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0846-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale C.A., Borrell L.N., Kimball S., et al. Plans to vaccinate children for coronavirus disease 2019: a survey of United States parents. J. Pediatr. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.021. a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale C.A., Borrell L.N., Shen Y., et al. Parental plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19 in New York City. Vaccine. 2021;39(36):5082–5086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.058. b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The State Council joint prevention and control mechanism of August 27, 2021 press release text Available access: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/fkdt/202108/f211dd79672642b7908ffb7575d020a1.shtml.

- The State Council joint prevention and control mechanism of September 7, 2021 press release text Available access: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/fkdt/202109/8b207c33c04145e4942ff946b53adc7c.shtml.

- Wan X., Huang H., Shang J., et al. Willingness and influential factors of parents of 3-6-year-old children to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1955606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhang R., Zhou Z., et al. Parental psychological distress and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: a cross-sectional survey in Shenzhen, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;292:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit M., Ozkaya-Parlakay A., Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine refusal in parents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021;40(4):e134–e136. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.X., Lin X.Q., Chen Y., et al. Determinants of parental hesitancy to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in China. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1967147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.