Abstract

This meta-narrative review on mental health early intervention support for LGBTQ+ youth aimed to develop a theoretical framework to explain effective mental health support. Using the RAMESES standards for meta-narrative reviews, we identified studies from database searches and citation-tracking. Data extraction and synthesis was conducted through conceptual coding in Atlas.ti. in two stages: 1) conceptual mapping of the meta-narratives; 2) comparing the key concepts across the meta-narratives to produce a theoretical framework. In total, 2951 titles and abstracts were screened and 200 full papers reviewed. 88 studies were included in the final review. Stage 1 synthesis identified three meta-narratives - psychological, psycho-social, and social/youth work. Stage 2 synthesis resulted in a non-pathological theoretical framework for mental health support that acknowledged the intersectional aspects of LGBTQ+ youth lives, and placed youth at the centre of their own mental health care. The study of LGBTQ+ youth mental health has largely occurred independently across a range of disciplines such as psychology, sociology, public health, social work and youth studies. The interdisciplinary theoretical framework produced indicates that effective early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth must prioritise addressing normative environments that marginalises youth, LGBTQ+ identities and mental health problems.

Keywords: Mental health, LGBTQ+, Youth, Adolescence, Sexual minority, Gender minority

Highlights

-

•

Despite elevated rates of poor mental health, LGBTQ + youth underutilize mental health services and often experience inadequate support.

-

•

There is a limited evidence-base examining LGBTQ + youth early intervention mental health support needs.

-

•

Early intervention services for LGBTQ + youth mental health must de-pathologize emotional distress, difficult thoughts and behaviours.

-

•

Early intervention support must address normative environments that marginalises youth, intersectional LGBTQ + identities and mental health.

-

•

Mental health support providers must understand individual lives, connect with LGBTQ+ youth, facilitate their autonomy and encourage agency.

1. Background

LGBTQ+1 young people report significantly higher rates of depression, self-harm, suicidality and poor mental health than cisgender and heterosexual youth (Amos, Manalastas, White, Bos, & Patalay, 2020; Irish et al., 2019; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2018; Semlyen, King, Varney, & Hagger-Johnson, 2016). In a pooled analysis of 12 UK population surveys, those who were under 35 and identified as LGB were twice as likely to report symptoms of poor mental health compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Semlyen et al., 2016). A recent meta-analysis of studies comparing suicidality in youth found that compared to cisgender and heterosexual youth, trans youth were six times, bisexual youth five times and LG youth four times more likely to report a history of attempted suicide (Di Giancomo et al., 2018). Longitudinal evidence also demonstrates that in the UK, these mental health disparities start as early as 10 years old (Irish et al., 2019). Despite this mental health inequality, LGBTQ+ youth have significantly higher unmet mental health need than their heterosexual peers (Williams & Chapman, 2011, 2012). Recent evidence suggests that although there is a greater mental health burden in this population, LGBTQ+ youth underutilize mental health services, do not access them until crisis point and often find them unhelpful (McDermott, 2015, McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, 2017). A recent UK study using a community sample (n = 789) found that only one fifth of participants had sought help from health services for their mental health problems (McDermott et al., 2017).

There is a limited understanding of why asking for help for mental health problems is problematic for LGBTQ+ youth. Research suggests the reluctance to access mental health services is because of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia, difficulties disclosing sexual and gender identity, and fears of being misunderstood (McDermott., 2015). Current studies show that LGBTQ+ youth are afraid of being judged, rejected and humiliated because of normative expectations of adolescent development, cis-heteronormativity and mental health (McDermott, 2015, McDermott & Hughes, 2016a, McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, 2017)

In addition to the underutilisation of mental health services (Acevedo-Polakovich, Bell, Gamache, & Christian, 2013), studies suggest LGBTQ+ youth have poor overall experience of mental health services and school-based support (McDermott & Hughes, 2016a; Williams & Chapman, 2011, 2015). Problems highlighted are a lack of engagement with practitioners, limited staff understanding of LGBTQ+ issues, and exclusion from the decisions made about young people's care (Brown, Rice, Rickwood, & Parker, 2016; (McDermott & Hughes, 2016a, McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, 2017)). Importantly, studies show that LGBTQ+ youth will seek mental health help online and from peers (Lucassen et al., 2018; McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, 2017, McDermott & Roen, 2015b, McDermott & Roen, 2016) and prefer accessing LGBTQ+ organizations for mental health support (Johnson et al., 2007; McDermott et al., 2016). Despite the recognition that LGBTQ+ youth are less likely to access mainstream mental health services, the evidence-base examining LGBTQ+ youth mental health support needs and service preferences is very limited. A systematic review found that research was more likely to identify barriers to accessing mental health support rather than facilitators to encourage engagement (Wilson & Cariola, 2019). In addition, there is an absence of focus on intersectional factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status and disability in LGBTQ+ youth mental health care (Craig, McInroy, Austin, Smith, & Engle, 2012; Newman et al., 2020; Riggs & Treharne, 2017). Newman et al. (2020) suggest that it is necessary to pay attention to the ‘affective dimensions of healthcare engagement’ (p.1) in order to understand how to develop inclusive healthcare for LGBTQ+ youth. The authors argue for a model of care that goes beyond ‘tolerant inclusivity in which sexually and gender diverse people are framed as different in spaces governed by normative practices, concepts, representations, language and hierarchies’ (p.2). Their research suggests ‘belonging’ is important to inclusive healthcare for LGBTQ+ youth, where there is an unconditional acceptance and recognition of gender and sexual diversity (see also McDermott & Roen, 2016).

There is minimal UK evidence and in this study we employed a theory-led review of the published literature on LGBTQ+ youth early intervention mental health support (i.e. prior to crisis care). We utilized the meta-narrative review (MNR) method because it can make sense of heterogeneous evidence from a variety of research paradigms that produces high order explanations for how and why complex services/interventions may work (Greenhalgh et al., 2011, Wong et al., 2013; Wong, Greenhalgh, & Buckingham, 2013). The aim of this MNR, part of a larger study, was to obtain a theoretical understanding of how early intervention mental health services can support LGBTQ+ youth with common mental health problems. The specific review questions were: 1) What empirical studies have been undertaken on mental health early intervention services and self-care support for LGBTQ + youth?; 2) What are the theoretical propositions for how and why these services/support work?

2. Methods

A scoping review confirmed the nascent nature of existing research on LGBTQ+ youth mental health early intervention support. The primary aim of the scoping review was to assess the size of the available published literature on LGBTQ+ youth mental health early intervention services/support research. Scoping review methodology can be used to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature and provide a roadmap for a subsequent full systematic review (Munn et al., 2018). We searched four main databases, from 2005, for research examining LGBT youth and mental health services, and research on mental health interventions aimed at LGBT youth. We located 55 relevant studies and no systematic reviews on the topic. The scoping review revealed a body of literature from divergent research paradigms such as medicine, clinical psychology, psychiatry, sociology, cultural studies, education, youth studies, social work and queer theory. This discovery informed our decision to utilize the meta-narrative review method because it offers a strategy to make use of a conflicting body of research from diverse research paradigms (Otte-Trojel & Wong, 2016).

We chose to utilize the MNR method rather than other theory-led review methods (e.g. realist review, meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis) for two reasons. Firstly, the scoping review revealed a heterogenous body of literature consisting of disparate research paradigms with different epistemological and ontological perspectives that have produced a disjointed empirical evidence-base. Secondly, our aim was to produce a theoretical explanation of mental health early intervention support for LGBTQ+ youth that could be tested within a case study evaluation methodology. A MNR is a distinct systematic theory-driven technique developed by Greenhalgh (2005) that is used to generate understanding from heterogeneous, complex, often contradictory evidence across diverse disciplines (Greenhalgh et al., 2011; Otte-Trojel, 2016).

Specifically, MNRs make sense of complex interventions/services by exploring the implications of different conceptualisations of a given topic across a range of research paradigms over time. The underlying assumption is that key constructs, in our case ‘sexual orientation’, ‘gender identity’, ‘mental health’, ‘youth’ and ‘help-seeking’, are conceptualized, theorized and empirically studied differently among research paradigms. A MNR is premised upon a constructivist epistemological approach that suggests that knowledge is produced within particular research traditions (e.g. sociological, psychological, biomedical). Consequently, a MNR aims to make sense of heterogenous bodies of literature by identifying, comparing and analysing the belief systems that exist within different research paradigms.

2.1. Search strategy

Using the RAMESES (Wong, 2013) standards for MNRs the protocol was registered with Prospero. The search terms were developed in four domain categories: a) sexual orientation and gender identity; b) age; c) mental health; and d) intervention/service. Searching was then undertaken via relevant electronic databases including both discipline specific databases and multidisciplinary databases to increase the scope. These included for example, Medline, CINAHL, Psycinfo, Academic Search Ultimate, Web of Science, British Education Index, NHS Evidence, Social Care Online. The electronic database search was supplemented by expert informants, journal hand searching, citation tracking, and informant-led grey literature online searches. All identified papers were then subject to the review procedure.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1.) was based upon the PICOS (Population Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework. However, in comparison to other forms of systematic review, meta-narrative review does not pre-define a ‘preferred’ study design. This is consistent with the principle of pragmatism i.e. that evidence most likely to promote sense making about the phenomenon (LGBTQ+ youth mental health support) and be most useful to the ‘intended audience’, is selected (Greenhalgh & Wong, 2013). Thus, Table 1 represents PICOS criteria adapted to capture the diversity of possible search results that is acceptable for inclusion within a meta-narrative review. The selection of papers for a MNR is an interpretative process that attempts to make sense of the literature to produce an account of how the research traditions develop over time. This MNR selection process was iterative i.e. it required a series of judgements within the research team about the relevance of particular research within that tradition. Papers published before 1990 were excluded because research published before this date were unlikely to be relevant given substantial changes in attitudes, policies and laws towards LGBTQ+ populations. The United Nation defines ‘youth’ as referring to people aged 15–24, but the age definition of youth varies across nations, disciplines and policies. We utilized an age criteria of under 26 years to capture the widest range of relevant research. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied independently by two members of the research team.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | • LGBTQ + youth under the age of 26 years old | • Non LGBTQ + youth • LGBTQ + people aged 26 and over |

| Intervention | • Early intervention services i.e. support and prevention prior to crisis care for LGBTQ+ youth experiencing common mental health problems: o anxiety o depression o obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) o self-harm o post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) o emerging personality disorders • Self-care support services i.e. a private, public or voluntary sector service, intervention or technology in which staff provide, facilitate and support self-care • Clinical, social, education, peer-support and online based services • Interventions delivered as part of a trial • Historic service provision |

• Crisis care • Inpatient services • Mental health services for general youth population • Studies of ‘self-care’ only i.e. without the involvement of any service agent/staff |

| Findings | • Data on service user, family, carer, service provider and mental health support for LGBTQ + youth • Empirical or conceptual data relevant to understanding early intervention/self-care mental health support for this population |

• Empirical or conceptual data on inpatient mental health services/crisis support • Empirical or conceptual data on psychosis/other mental health conditions • Suicidality • Prevalence studies |

| Study details | • Peer-reviewed full text articles • Research published in books • Grey literature • All study designs • Published after 1990 • English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French |

• Opinion papers, editorials, dissertations and theses. • Published before 1990 • Published in any language other than English, Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese |

2.3. Quality assessment

Systematic review methodology does not have a standard quality appraisal framework. We drew on the EPPI-Centre ‘Weight of Evidence Framework’ (Gough, 2007) and recommendations for theory-led systematic reviews (Jagosh et al., 2011) to devise a quality appraisal tool (Table 2) that focussed on the relevance to the review question and the quality standard in relation to the discipline of origin. The tool was applied by two members of the research team.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal tool.

| Relevance to the review question. | 1. Does the full-text paper describe early intervention mental health services for LGBTQ+ young people empirically or conceptually? |

| 2. Does the full-text paper describe self-care support services for LGBTQ+ young people empirically or theoretically? | |

| Quality standard in relation to the discipline of origin. | 3. Does the full-text paper appropriately describe the research setting including the aim and objectives? |

| 4. Does the full-text paper fully detail the empirical research in a rigorous way (i.e., description of methodology, methods, data collection, analysis and ethics)? | |

| 5. Are the interpretations and conclusions robust? |

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction and synthesis was simultaneously conducted using the data analysis software Atlas.ti. Three members of the research team developed a data extraction and synthesis coding schema (Table 3) and this was applied to the included studies. The use of Atlas.ti enabled easy comparison and contrast of the extracted data across the 88 included studies for the synthesis of the literature.

Table 3.

Data extraction and synthesis coding schema.

| Data extraction code & definition | Sub-codes |

|---|---|

| Context: Describes the setting in which the research or discussion about mental health support takes place |

Clinical, Community, Online, Other, School |

| Finding: Any findings in the papers | Conceptual, Empirical |

| Study Design: Explicit research design stated | Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Method, Systematic review, Other e.g. clinical case |

| Theoretical Perspective: Explicit statement about the theoretical orientation of the study | |

| Intervention/service: The intervention or support service that the study involves. |

|

|

Synthesis code & definition |

Sub-codes |

| Help-seeking: Conceptualization of help-seeking | Access, Autonomy, Barriers, Cycle of avoidance, Health behaviour, Health information, Other, Power(lessness), Stigma |

| LGBTQ+ Identities: Conceptualization of relationship between LGBTQ + identities and mental health | Decompensation model, Essentialist, Heteronormativity, Homophobia, Intersectionality, Marginalisation, Minority Stress, Psychological Mediation Framework, Victimization |

| Mental Health: Conceptualization of mental health | Biomedical, Critical, Individualising, Other, Pathologizing, Psychological, Psycho-social |

| Youth: Conceptualization of youth | Adolescent psychological development, Autonomy, Biological, Other |

In stage one of the synthesis, multiple research team members used the extracted data to identify the research paradigms and map each meta-narrative. In this way the different research traditions ‘become the unit of analysis’ (Otte-Trojel, 2016). For each research paradigm we asked key questions: (1) How has each tradition conceptualized the topic? (2) What theoretical approaches and methods did they use? (3) What are the main empirical findings? (Wong, Greenhalgh, & Buckingham, 2013).

Stage 2 of the synthesis compared the key dimensions across the research paradigms to generate a higher order theoretical understanding of how and why interventions/services might work. This was conducted iteratively, using 5 distinct analytical steps that were guided by the principles of a MNR: pragmatism; pluralism; historicity; contestation; reflexivity; and peer review (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2005). We moved between these 5 steps and the key question we asked across the research paradigms was ‘what are the implications of the contested concepts for developing early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ + youth?’

3. Results

3.1. Search results

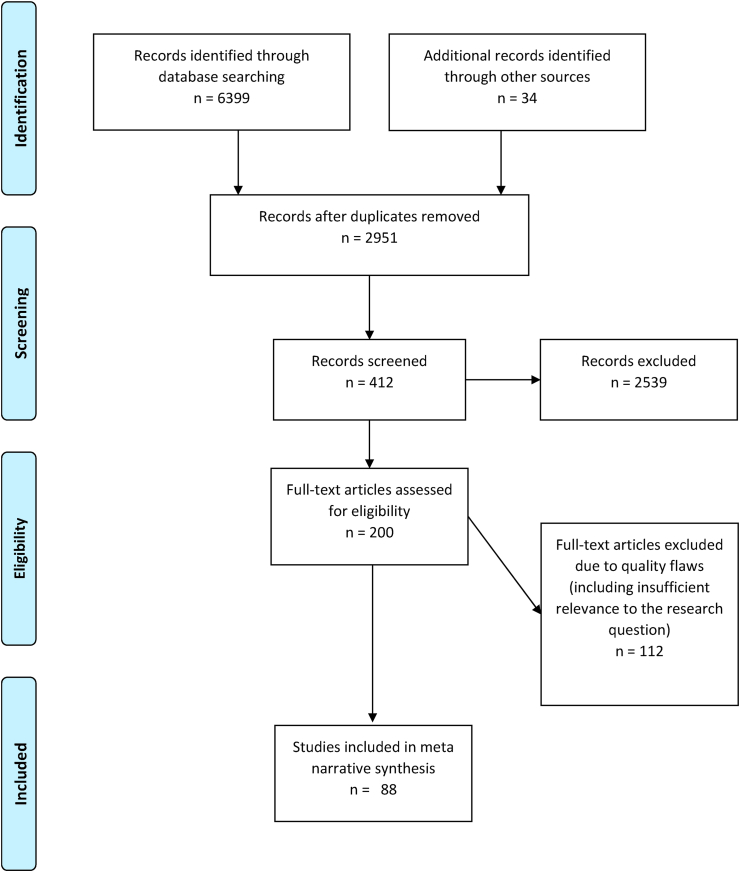

The search was conducted between March and June 2019. In total, 2951 titles and abstracts were screened and 200 full papers reviewed. 81 were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria and 31 studies were excluded for quality reasons. 88 papers remained for inclusion in the final analysis (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flowchart).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

3.1.1. Stage 1. Synthesis - key research meta-narratives

We conceptualized the included literature into three meta-narratives: psychology, psycho-social, social/youth work (see Table 4 for included papers by paradigm). It is important to understand these are meta-narratives i.e. bodies of knowledge that have a shared approach to the topic. They do not refer to individual disciplines. We outline below characteristics of these meta-narratives for each of the conceptual areas. There were often over-laps between the papers and it was sometimes difficult to draw boundaries. For clarity we grouped studies based on the underlying conceptualization of mental health rather than the discipline of the author or journal.

Table 4.

Included literature by paradigm.

Theoretical literature.

Meta-narrative 1: Psychology

The psychology meta-narrative focus is the brain & behaviour with the aim of understanding mental distress, rather than mental disorder, and helping an individual to adjust to their circumstances. A high proportion of the publications within this paradigm were produced by psychologists and published in psychology journals. The dominant ontological and epistemological approach within the meta-narrative is positivist and consequently the research methods utilized are quantitative, typically using pre-test/post-test survey methods and standardised validated measures to undertake empirical trial research about interventions. The theoretical basis of these studies most often relied on Meyer’s (2003) Minority Stress Framework in which LGBTQ+ identity is fixed and a discrete category. For example a paper may include measures of ‘distal stressors’ such as family homophobia and the impact on individual psychological functioning and identity development. In this meta-narrative there was very little theorisation of youth and the under-pinning presumption was adolescent development.

In the psychology meta-narrative, the individual is the key object of study with the central aim to affect cognitive/behaviour change for individual LGBTQ+ youth. As a consequence, the paradigm concentrates on individual level interventions such as CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) e.g. AFFIRM an intervention aimed at trans youth and coping skills (Craig & Austin, 2016) and Rainbow SPARX, an online CBT programme aimed at sexual minority youth and depression (Lucassen, Merry, Hatcher, & Frampton, 2015). Far less attention is paid to wider socio-cultural context of interventions.

Meta-narrative 2: Psycho-social

The psycho-social meta-narrative considers the interplay of individual psychology and social contextual factors in mental health without conceptualising the two as discrete entities. This scholarship specifically aims to address the polarization in debates between psychology and socio-historical perspectives of sexuality and gender (Johnson, 2014, McDermott & Roen, 2016). The ontological and epistemological foundations of the papers within this meta-narrative was more varied (social constructionist, realist, positivist) and the generation of knowledge more interdisciplinary (and research teams multidisciplinary) and published across a wider range of journal types. Although quantitative methods remained the single most common approach, a broader range of methods was used here than in the psychology meta-narrative. However, mental health was frequently measured as per the psychological meta-narrative through standardised validated psychological measures.

As with the psychology meta-narrative, Meyer's (2003) Minority Stress Theory was the dominant way in which LGBTQ+ youth mental health was conceptualized and the concept of youth was again under-theorised. There was also a significant use of queer theory and heteronormativity to critique normative adolescent development, mental health and minority stress theory. In addition, there is a more nuanced appreciation of the intersection of LGBTQ+ identity with other factors such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status. The support and interventions in this meta-narrative are more heterogenous than those in the psychology meta-narrative. Individual support service/interventions are more likely to be multifaceted and include a social component (e.g. school belonging (McLaren, Schurmann, & Jenkins, 2015)) or delivery context (e.g. summer camp (Vincke & van Heeringen, 2004)) and be delivered in a community e.g. youth health centre (Oransky, Burke, & Steever, 2018) or school setting e.g. Gay-Straight Alliances (Heck, Flentje, & Cochran, 2013).

Meta-narrative 3: Social/youth work

This meta-narrative contains social/youth work scholarship or practice that considers individuals/youth in relation to their wider communities and resources. The ‘object of study’ for this meta-narrative is LGBTQ+ youth within their wider social context and much more attention is given to youth and their social world than in the other two meta-narratives. Mental health is usually loosely defined and untheorized.

The dominant ontological and epistemological approach is social constructivist and interpretivist. Methodologically, this meta-narrative, congruent with the emphasis on youth participation, overwhelmingly uses a qualitative methodology frequently in collaboration with LGBTQ+ (youth) organizations. Youth is rarely theorised and the dominant conceptual framework regarding LGBTQ+ youth mental health is usually implicitly minority stress theory. Explicitly attending to cultural and ethnic diversity, this paradigm includes an intersectional perspective in theory and research practice, which means compared to the psychological and psycho-social meta-narratives, there is a departure from considering LGBTQ+ youth as one homogenous group.

The majority of the support/interventions discussed in this meta-narrative are social (rather than individual) and based in community (e.g. community support programme for Chinese trans youth (Kwok, 2018)), school settings (e.g. mental health delivery in schools (Wofford, 2017)), and (LGBTQ+) youth specific organizations (Gamarel, Walker, Rivera, & Golub, 2014). The interventions and recommendations for support from this meta-narrative was based on the experiences of LGBTQ+ youth as opposed to being ‘filtered’ through the perspectives of (adult) clinical or school perspectives.

3.1.2. Stage 2. Synthesis - developing a theoretical framework

The framework we have produced is ‘theoretical’ (see Fig. 2) and it is not a blueprint for a mental health support service. The framework contains the key dimensions, derived from the literature, of a service for successfully supporting, at an early stage, LGBTQ+ youth with common mental health problems. It draws on models found in the literature that attempt to capture the multi-level (macro, meso, micro) interacting complex factors required to support the mental health of LGBTQ+ youth (Oransky et al., 2018). Our framework has a critical approach to LGBTQ+ youth mental health support, paying attention to three key contestations across the meta-narratives: i) the conceptualization of adolescence/youth; ii) theorisations of mental health; iii) the theoretical propositions for why LGBTQ+ populations have elevated rates of poor mental health.

Fig. 2.

Theoretical non-pathologizing framework for providing mental health support to LGBT+ youth.

3.2. Explaining the theoretical framework

3.2.1. Macro outer ring 1

The outer ring represents the macro level dimensions of power, norms and socio-economic material conditions that are maintained through institutions, laws, discourses and people. These impact on how a LGBTQ+ young person may think about themselves, the actions they may take, their access to resources, how others may interact with them and their mental health. At the macro level the effects of Heteronorms (the dominance of cis-heterosexuality where gender identities and bodies align and everyone is assumed heterosexual) on LGBTQ+ youth mental health is of paramount importance. Heteronormativity is maintained through direct homo/bi/trans phobia and discrimination, in addition to marginalisation, silence, invisibility, misrepresentation and exclusion of LGBTQ+ sexualities and genders. Mental health support must have an anti-oppressive and social justice approach in which LGBTQ+ youth can learn to understand, cope with, and reject heteronormativity, for example, through CBT psycho-education or peer-support groups. Normative Youth refers to the social norm where youth are positioned as less than adults and they are configured as passive subjects ‘waiting’ for adulthood. In many cases youth emotional distress is viewed as pathology, ignored and temporalized. To counter the disempowerment of youth and the diminishing of their distress, support services require an anti-paternalist, youth-centred approach enabled through advocacy & collaboration. Bio-Psych Power refers to the pathologizing impact of biomedicine and psychiatry on LGBTQ+ identities and youth mental health. Mental health support must hold the perspective that LGBTQ identity and difficult emotions are not a sign of psychological abnormality. Intersectionality means mental health support must acknowledge the multiple discriminations that arise as a result of multiple identity characteristics such as race, ethnicity, faith and disability. LGBTQ+ may not be the central facet of youth identity and experience. The Socio-economic and Material Conditions refers to mental health support needing to understand the social and financial disadvantage experienced by youth. Most youth have limited access to resources and finances and are dependent on family or carers. Those without families, BAME, homeless, asylum seekers, refugees, and trans, are especially precarious and vulnerable.

3.2.2. Meso inner ring 2

The meso level components of the framework are important to the over-arching provision of mental health support. Recognition refers to the need for mental health support to acknowledge through affirmation the plurality and fluidity of gender and sexual self-definition. This should foster a positive identity where the individual is valued, understood and accepted. Relationality refers to the importance of connection to others as a way to support and improve mental health. Connections with peers and trusted adults may be more effective at reducing poor mental health where ‘mutual-care’ in addition to ‘self-care’ is operationalized. Belonging means LGBTQ+ youth should feel included, comfortable and like they ‘fit in’ the support service. Mental health support should be non-judgemental and inclusive, encouraging coping, trust and understanding. Becoming means there is not a fixed pathway to a sexual or gendered identity or a final destination identity. Mental health support must prioritise gendered and sexual self-definition, space and flexibility for change and not make assumptions. The emotional, cultural, psychological and physical Safety of youth should be paramount to mental health support. This must prioritise fostering trust, confidentiality, privacy through space and staff. Intelligibility is the capability of being understood, to be comprehended for different experiences connected to different and intersecting categorisations of identity.

3.2.3. Micro ring 3

The micro ring features are important to how the individual is regarded within the mental health support service. Agency means youth must be treated as acting, knowing subjects with support employing an advocacy, empowerment, collaboration and joint decision-making approach. Autonomy refers to youth self-determination and youth having an active voice in their care. Mental health support should promote self-efficacy, self-awareness and identifying personal strengths. Subjugated knowledges indicates that valuing youth knowledge and experience is central for delivering appropriate support. Services should operate through a strength-based approach to youth competency. Resistance refers to support that enables youth to refuse to be diminished by their identity, age and mental health status. Positive mental health can be encouraged through developing coping strategies and building confidence, resilience, self-esteem and understanding through, for example, psycho-education, activism, art, therapy, celebration, fun.

3.2.4. Centre ring 4

At the centre of the framework is Mental Health which was conceptualized in a variety of ways in the 3 meta-narratives we identified. Our theoretical framework notes mental health can be a diagnostic category. It is also a complex phenomenon incorporating Emotions, Feelings, Distress and Subjectivity that are a natural part of human suffering and misery and not an indication of psychological abnormality. Early intervention mental health support must start with LGBTQ+ youth subjective assessment of their mental health needs rather than symptomology and diagnosis.

4. Discussion

This MNR aimed to assess the evidence on mental health early intervention services and support for LGBTQ+ youth. The theoretical framework we have devised, based on an interpretative synthesis of the evidence, is aligned with the de-medicalization of human misery and suffering because the pathologization of emotional distress, difficult feelings/thoughts and behaviours has a stigmatizing impact on individuals and societies. Our framework is aimed at supporting youth with common mental health problems at an early point in their difficulties. It does not presume that psychiatry (which hardly featured in the literature we found) or individual psychology present the most effective ways of understanding how to intervene. Our starting point is that LGBTQ+ youth do not need a mental health diagnosis before they can be supported to improve their mental health. A mental health diagnosis should not stop young people accessing mental health support, and it is not always necessary i.e. a young person's mental health can be improved without a mental health diagnosis. Our framework suggests that early intervention must be early and the subjective assessment of mental health by a young person is sufficient to access support.

A further fundamental element of the framework to support LGBTQ+ youth mental health is to understand that they live in a heteronormative world that despite improvements continues to either explicitly denigrate LGBTQ+ identities or marginalise and silence those lives. This was acknowledged across all 3 meta-narratives and strongly suggests that youth must be supported to exist within/resist against these difficult normative environments.

We have interpretively synthesized the literature to produce an individual and social theoretical framework for supporting LGBTQ+ youth mental health. We understand LGBTQ+ youth mental health as arising from intersectional and complex factors. Our framework de-medicalizes emotional distress and promotes youth-centred support that attends to the multi-factored influences on mental health. Our framework suggests that those who provide support must understand individual lives, must connect with youth, must collaborate facilitating the young person's autonomy and encourage agency. The framework aims to have applicability across a variety of settings such as school, healthcare, online, community and youth work.

A central characteristic of the MNR method is premised upon Kuhn's (1962) epistemological perspective that what we come to know about the world is not homogenous and linear. Scientific knowledge progresses through paradigms, that ebb and flow and develop in relation to each other and their ability to explain a particular phenomenon. The ‘storylines’ (Greenhalgh et al., 2005) of the meta-narratives that contribute to the evidence base about LGBTQ+ mental health have been heavily shaped by legal, policy, biomedical, academic and public discourses/attitudes to sexual and gender diversity, and by the social movements that have aimed to gain equality for LGBTQ+ people. These have also been crucial to the developments of research on LGBTQ+ youth mental health. As a result of this liberalization, albeit uneven, we now know and acknowledge the prevalence of the problem, but we must now intervene to tackle this mental health inequality. This is where we are stuck, we have much less research about the ways of addressing LGBTQ+ youth mental health and promoting wellbeing, across all research paradigms.

Across the literature we reviewed, scholars worldwide were struggling with similar difficulties in trying to understand the problem and provide solutions. The background for each paper was the marginalisation and stigmatisation of young LGBTQ+ lives, the impact this had on their mental health, the dearth of appropriate mental health support and the need for research to support the development of effective mental health provision. The study of LGBTQ+ youth mental health has largely occurred across the disciplines of psychology, sociology, public health, social work and youth studies, which until now have operated independently of each other. Our interdisciplinary approach indicates that effective early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth must prioritise addressing normative environments that marginalises youth, LGBTQ+ identities and mental health problems. We appreciate that these macro level changes may be difficult and take time. Perhaps indicative of this, we did not find any interventions that sought to change these normative environments beyond community/school level.

The strength of this review is that it utilized a theory-led systematic review methodology to detail the underlying theory of effective mental health care. This is the first, to our knowledge, theoretical framework to be produced for supporting LGBTQ+ youth mental health and is a significant advancement in developing effective services and interventions because eventually, after testing empirically, it will provide the principles for appropriate LGBTQ+ youth mental health support. However, the review is of course limited by language and there may be important evidence written in countries that we were unable to include. In addition, we realise that the adaptation of the PICOS formula for selecting studies for MNR methodology is unwise. This is because the PICOS framework, although widely used within SR methodology, cannot be easily applied through an interpretive and iterative approach. Most clearly the theoretical framework is exactly that, theoretical, and it must now be tested empirically so that we and LGBTQ+ young people might judge its acceptability.

Declaration of competing interest

The work reported in this paper was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, Grant No: NIHRDH-HS&DR/17/09/04. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

We use LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer+) to refer collectively to sexual minority and gender diverse identities because of the proliferation of terms used by young people. References to other research, uses the cited author's original terminology for sexuality/gender.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abbott J.A.M., Klein B., McLaren S., Austin D.W., Molloy M., Meyer D., et al. Out & online; effectiveness of a tailored online multi-symptom mental health and wellbeing program for same-sex attracted young adults: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Polakovich I.D., Bell B., Gamache P., Christian A.S. Service accessibility for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Youth & Society. 2013;45(1):75–97. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11409067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen K.D., Hammack P.L., Himes H.L. Analysis of GLBTQ youth community-based programs in the United States. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59(9):1289–1306. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.720529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos R., Manalastas E.J., White R., Bos H., Patalay P. 2020. Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: A contemporary national cohort study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A., Craig S.L. Empirically supported interventions for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal Of Evidence-Informed Social Work. 2015;12(6):567–578. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2014.884958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A., Craig S.L., D'Souza S.A. An AFFIRMative cognitive behavioral intervention for transgender youth: Preliminary effectiveness. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2018;49(1):1–8. doi: 10.1037/pro0000154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bain C.L., Grzanka P.R., Crowe B.J. Toward a queer music therapy: The implications of queer theory for radically inclusive music therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2016;50:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D., Durr P., Scott P. Youth chances report. Youth chances charity; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bridget J., Lucille S. Lesbian youth support information service (LYSIS): Developing a distance support agency for young lesbians. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 1996;6(5):355–364. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1298(199612)6. :5<355::Aid-casp386>3.0.Co;2-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A., Rice S., Rickwood D., Parker A. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal Of The Pacific Rim College Of Psychiatrists. 2016;8(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/appy.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M.N., Montague E., Mohr D.C. Initial design of culturally informed behavioral intervention technologies: Developing an mHealth intervention for young sexual minority men with generalized anxiety disorder and major depression. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(12) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busa S., Janssen A., Lakshman M. A review of evidence based treatments for transgender youth diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. Transgender Health. 2018;3(1):27–33. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir S.R., Wang K., Pachankis J.E. What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit”. Journal of Social Issues. 2017;73(3):586–617. doi: 10.1111/josi.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Hayes S.F. Counseling and advocacy with transgendered and gender-variant persons in schools and families. Journal of Humanistic Counseling Education and Development. 2001;40(1):34–49. doi: 10.1002/j.2164-490X.2001.tb00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang S.-Y., Fleming T., Lucassen M.F.G., Fouche C., Fenaughty J. From secrecy to discretion: The views of psychological therapists on supporting Chinese sexual and gender minority young people. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;93:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohler B.J., Hammack P.L. The psychological world of the gay teenager: Social change, narrative, and "normality. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(1):47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9110-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter R.W., Sang J.M., Louth-Marquez W., Henderson E.R., Espelage D., Hunter S.C., DeLucas M., Abebe K.Z., Miller E., Morrill B.A., Hieftje K., Friedman M.S., Egan J.E. Pilot Testing the Feasibility of a Game Intervention Aimed at Improving Help Seeking and Coping Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR research protocols. 2019;8(2):e12164. doi: 10.2196/12164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover R. Routledge; London: 2012. Queer youth suicide, culture & identity: Unliveable lives. [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.L., Austin A. The AFFIRM open pilot feasibility study: A brief affirmative cognitive behavioral coping skills group intervention for sexual and gender minority youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;64:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S., Austin A., Alessi E. Gay affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual minority youth: A clinical adaptation. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;41(3):258–266. doi: 10.1007/s10615-012-0427-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.L., Austin A., Alessi E.J., McInroy L., Keane G. Minority stress and HERoic coping among ethnoracial sexual minority girls: Intersections of resilience. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2017;32(5):614–641. doi: 10.1177/0743558416653217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.L., Austin A., Huang Y.T. Being humorous and seeking diversion: Promoting healthy coping skills among LGBTQ+ youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2018;22(1):20–35. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2017.1385559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.L., Furman E. Do marginalized youth experience strengths in strengths-based interventions? Unpacking program acceptability through two interventions for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Social Service Research. 2018;44(2):168–179. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2018.1436631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.L., McInroy L., Austin A., Smith M., Engle B. Promoting self-efficacy and self-esteem for multiethnic sexual minority youth: An evidence-informed intervention. Journal of Social Service Research. 2012;38(5):688–698. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2012.718194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T.S., Saltzburg S., Locke C.R. Supporting the emotional and psychological well being of sexual minority youth: Youth ideas for action. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(9):1030–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T.S., Saltzburg S., Locke C.R. Assessing community needs of sexual minority youths: Modeling concept mapping for service planning. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2010;22(3):226–249. doi: 10.1080/10538720903426354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo E., Krausz M., Colmegna F., Aspesi F., Clerici M. Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018;172(12):1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erney R., Weber K. Not all children are straight and white: Strategies for serving youth of color in out-of-home care who identify as LGBTQ. Child Welfare. 2018;96(2):151–177. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000432337700009. [Google Scholar]

- Fay . The Proud Trust; Manchester: 2017. Getting it Right: What LGBT+ young people want and need in Greater Manchester. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson K.M., Maccio E.M. Promising programs for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Social Service Research. 2015;41(5):659–683. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2015.1058879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J.B., Hill Y.N., Burns M.N. Usability of a culturally informed mHealth intervention for symptoms of anxiety and depression: Feedback from young sexual minority men. JMIR Human Factors. 2017;4(3) doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7392. e22-e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel K.E., Walker J.N.J., Rivera L., Golub S.A. Identity safety and relational health in youth spaces: A needs assessment with LGBTQ youth of color. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2014;11(3):289–315. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1032932&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,shib&user=s1523151 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gillig T.K., Miller L.C., Cox C.M. She finally smiles horizontal ellipsis for real": Reducing depressive symptoms and bolstering resilience through a camp intervention for LGBTQ youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 2019;66(3):368–388. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1411693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough D. Weight of evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education. 2007;22(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Robert G., Macfarlane F., Bate P., Kyriakidou O., R P. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(2):417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Wong G. 2013. Training materials for meta-narrative reviews.http://www.ramesesproject.org/media/Meta_narrative_reviews_training_materials.pdf Retrieved from Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Wong G., Westhorp G., R P. Protocol – realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: Evolving standards (RAMASES) BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara O. Exploring the emotional health of LGBT+ people in NI. Belfast. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M.L. How does sexual minority stigma "get under the skin"? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M.L., Pachankis J.E. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2016;63(6):985–+. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck N.C. The potential to promote resilience: Piloting a minority stress-informed, GSA-based, mental health promotion program for LGBTQ youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2(3):225–231. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck N.C., Flentje A., Cochran B.N. Offsetting risks: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2013;1(S):81–90. doi: 10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica S., Alman A., Jackowich S., Kwon P. Empirically based psychological interventions with sexual minority youth: A systematic review. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2018;5(3):313–323. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnke M., O'Brien P. Discrimination against same sex attracted youth: The role of the school counsellor. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2008;18(1):67–75. doi: 10.1375/ajgc.18.1.67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono G. An affirmative mindfulness approach for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth mental health. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10615-018-0656-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ioverno S., Belser A.B., Baiocco R., Grossman A.H., Russell S.T. The protective role of gay-straight alliances for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2016;3(4):397–406. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M., Solmi F., Mars B., King M., Lewis G., Pearson R.M., Pitman A., Rowe S., Srinivasan R., Lewis G. Depression and self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood in sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals in the UK: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet. Child & adolescent health. 2019;3(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J., Pluye P., Macaulay A.C., Salsberg J., Henderson J., Sirett E.…Green L.W. Assessing the outcomes of participatory research: protocol for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing the literature for realist review. Implementation science : IS. 2011;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. Sexuality: A psychosocial manifesto. Policy Press; Cambridge: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Faulkner P., Jones H., Welsh E. Brighton: University of Brighton; 2007. Understanding suicidal distress and promoting survival in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn T.S. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok D.K. Community support programme: Support for Chinese trans∗ students experiencing genderism. Sex Education-Sexuality Society and Learning. 2018;18(4):406–419. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1428546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok D.K., Winter S., Yuen M. Heterosexism in school: The counselling experience of Chinese tongzhi students in Hong Kong. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2012;40(5):561–575. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2012.718735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe A., Crooks C. GSA members' experiences with a structured program to promote well-being. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2018;15(4):300–318. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2018.1479672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe A., Dunlop C., Crooks C. Feasibility and fit of a mental health promotion program for LGBTQ+ youth. Journal of Youth Development. 2018;13(4):100–117. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2018.585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeFrancois B.A. Queering child and adolescent mental health services: The subversion of heteronormativity in practice. Children & Society. 2013;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00371.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen M.F.G., Hatcher S., Fleming T.M., Stasiak K., Shepherd M.J., Merry S.N. A qualitative study of sexual minority young people's experiences of computerised therapy for depression. Australasian Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):268–273. doi: 10.1177/1039856215579542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen M.F.G., Hatcher S., Stasiak K., Fleming T., Shepherd M., Merry S.N. The views of lesbian, gay and bisexual youth regarding computerised self-help for depression: An exploratory study. Advances in Mental Health. 2013;12(1):22–33. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2013.12.1.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen M.F.G., Merry S.N., Hatcher S., Frampton C.M.A. Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22(2):203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen M., Samra R., Iacovides I., Fleming T., Shepherd M., Stasiak K., et al. How LGBT+ young people use the internet in relation to their mental health and envisage the use of e-therapy: Exploratory study. JMIR Serious Games. 2018;6(4) doi: 10.2196/11249. e11249-e11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum C., McLaren S. Sense of belonging and depressive symptoms among GLB adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 2010;58(1):83–96. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.533629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E. Asking for help online: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans youth, self-harm and articulating the "failed’ self. Health. 2015;19(6):561–577. doi: 10.1177/1363459314557967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E., Hughes E., Rawlings V. Lancaster University; Lancaster: 2016. Queer Futures: Understanding lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) adolescents’ suicide, self-harm and help-seeking behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E., Hughes E., Rawlings V. Norms and normalisation: Understanding LGBT youth suicide and help-seeking. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2017;20(2):156–172. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1335435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E., Roen K., Piela A. Explaining self-harm: Youth cybertalk and marginalized sexualities and genders. Youth & Society. 2015;47(6):873–889. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13489142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E., Roen K. Queer youth suicide and self harm: Troubled subjects, troubling norms. Palgrave Macmillan; Cambridge: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald K. Social support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2018;39(1):16–29. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren S., Schurmann J., Jenkins M. The relationships between sense of belonging to a community GLB youth group; school, teacher, and peer connectedness; and depressive symptoms: Testing of a path model. Journal of Homosexuality. 2015;62(12):1688–1702. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1078207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros D.M., Seehaus M., Elliott J., Melaney A. Providing mental health services for LGBT teens in a community adolescent health clinic. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2004;8(3/4):83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar B.M., Wang K., Pachankis J.E. The moderating role of internalized homonegativity on the efficacy of LGB-affirmative psychotherapy: Results from a randomized controlled trial with young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84(7):565–570. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MindOut Working with LGBTQ people report. Brighton, MINDOUT. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Peters M.D., Stern C., Tufanaru C., McArthur A., Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;18(143) doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman C.E., Prankumar S.K., Cover R., Rasmussen M.L., Marshall D., Aggleton P. Inclusive health care for LGBTQ+ youth: Support, belonging, and inclusivity labour. Critical Public Health. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2020.1725443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nodin N., Peel E., Tyler A., Rivers I. PACE; London: 2015. The RARE research report: LGB&T mental health - risk and resilience explored. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oransky M., Burke E.Z., Steever J. An interdisciplinary model for meeting the mental health needs of transgender adolescents and young adults: The mount sinai adolescent health center approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otte-Trojel T., Wong G. Going beyond systematic reviews: Realist and meta-narrative reviews. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2016;222:275–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paceley M.S. Gender and sexual minority youth in nonmetropolitan communities: Individual- and community-level needs for support. Families in Society-the Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2016;97(2):77–85. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.2016.97.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis J.E., Goldfried M.R. Expressive writing for gay-related stress: Psychosocial benefits and mechanisms underlying improvement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(1):98–110. doi: 10.1037/a0017580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter K.R., Scannapieco M., Blau G., Andre A., Kohn K. Improving the mental health outcomes of LGBTQ youth and young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Social Service Research. 2018;44(2):223–235. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2018.1441097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta-Chiarolli M., Martin E. “Which sexuality? Which service?”: Bisexual young people's experiences with youth, queer and mental health services in Australia. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2009;6(2/3):199–222. doi: 10.1080/19361650902927719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepping C.A., Lyons A., McNair R., Kirby J.N., Petrocchi N., Gilbert P. A tailored compassion-focused therapy program for sexual minority young adults with depressive symotomatology: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology. 2017;5(1) doi: 10.1186/s40359-017-0175-2. 5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry N.S., Chaplo S.D., Baucom K.J.W. The impact of cumulative minority stress on cognitive behavioral treatment with gender minority individuals: Case study and clinical recommendations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2017;24(4):472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C., Ellasante I., Korchmaros J.D., Haverly K., Stevens S. iTEAM: Outcomes of an affirming system of care serving LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness. Families in Society-the Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2016;97(3):181–190. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.2016.97.24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx C.N., Coulter R.W.S., Egan J.E., Matthews D.D., Mair C. Associations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning-inclusive sex education with mental health outcomes and school-based victimization in U.S. High school students. Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication Of The Society For Adolescent Medicine. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs D.W., Ansara G.Y., Treharne G.J. An evidence-based model for understanding the mental health experiences of transgender Australians. Australian Psychologist. 2015;50(1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/ap.12088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs D.W., Treharne G.J. Decompensation: A novel approach to accounting for stress arising from the effects of ideology and social norms. Journal of Homosexuality. 2017;64(5):592–605. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1194116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson A. Living for the city: Voices of black lesbian youth in detroit. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2010;14(1):61–70. doi: 10.1080/10894160903058899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski M., Chow S., Scanlon C.P. Meeting the needs of LGBTQ youth: A “relational assets” approach. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2009;6(2/3):174–198. doi: 10.1080/19361650903013493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort T.G.M., Bos H.M.W., Collier K.L., Metselaar M. School environment and the mental health of sexual minority youths: A study among Dutch young adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(9):1696–1700. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.183095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansfaçon A.P., Hébert W., Lee E.O.J., Faddoul M., Tourki D., Bellot C. Digging beneath the surface: Results from stage one of a qualitative analysis of factors influencing the well-being of trans youth in Quebec. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2018;19(2):184–202. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1446066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semlyen J., King M., Varney J., Hagger-Johnson G. Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: Combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(67) doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N.G., Hart T.A., Kidwai A., Vernon J.R.G., Blais M., Adam B. Results of a pilot study to ameliorate psychological and behavioral outcomes of minority stress among young gay and bisexual men. Behavior Therapy. 2017;48(5):664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinke J., Root-Bowman M., Estabrook S., Levine D.S., Kantor L.M. Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: Formative research on potential digital health interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;60(5):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum S. Tenoch's gender journey: Case study of a 13-year-old Mexican refugee with aboriginal ancestry - naming the gaps between theory and practice. First Peoples Child & F amily Review. 2012;7(2):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey R.B., Anhalt K. Mindfulness as a coping strategy for bias-based school victimization among latina/o sexual minority youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2016;3(4):432–441. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey R.B., Ryan C., Diaz R.M., Russell S.T. High school gay-straight alliances (GSAs) and young adult well-being: An examination of GSA presence, participation, and perceived effectiveness. Applied Developmental Science. 2011;15(4):175–185. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.607378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey R.B., Ryan C., Diaz R.M., Russell S.T. Coping with sexual orientation-related minority stress. Journal of Homosexuality. 2018;65(4):484–500. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey R.B., Syvertsen A.K., Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trust P. The Proud Trust; Manchester: 2016. LGBT young people's health in the UK: A literature review with a focus on needs, barriers and practice. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vincke J., Van Heeringen K. Confidant support and the mental wellbeing of lesbian and gay young adults: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2002;12(3):181–193. doi: 10.1002/casp.671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincke J., van Heeringen K. Summer holiday camps for gay and lesbian young adults: An evaluation of their impact on social support and mental well-being. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47(2):33–46. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagaman M.A., Keller M.F., Cavaliere S.J. What does it mean to be a successful adult? Exploring perceptions of the transition into adulthood among LGBTQ emerging adults in a community-based service context. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2016;28(2):140–158. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2016.1155519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson J.M., Lawler S.M., Romijnders K.A., Armstead A.B., Bauldry J., Montrose C. Exploratory analyses of risk behaviors among GLBT youth attending a drop-in center. Health Education & Behavior. 2018;45(2):217–228. doi: 10.1177/1090198117715668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson J.M., Schick V.R., Romijnders K.A., Bauldry J., Butame S.A., Montrose C. Social support, depression, self-esteem, and coping among LGBTQ adolescents participating in hatch youth. Health Promotion Practice. 2017;18(3):358–365. doi: 10.1177/1524839916654461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K.A., Chapman M.V. Comparing health and mental health needs, service use, and barriers to services among sexual minority youths and their peers. Health & Social Work. 2011;36(3):197–206. doi: 10.1093/hsw/36.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K.A., Chapman M.V. Unmet health and mental health need among adolescents: The roles of sexual minority status and child-parent connectedness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(4):473–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K.A., Chapman M.V. Mental health service use among youth with mental health need: Do school-based services make a difference for sexual minority youth? School Mental Health. 2015;7(2):120–131. doi: 10.1007/s12310-014-9132-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C., Cariola L.A. LGBTQI+ youth and mental health: A systematic review of qualitative research. Adolescent Research Review. 2019;5:187–211. doi: 10.1007/s40894-019-00118-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wofford N.C. Mental health service delivery to sexual minority and gender non-conforming students in schools: A winnicottian approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2017;34(5):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10560-016-0482-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G., et al. RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Medicine. 2013;11(21) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G., Greenhalgh T., Buckingham J., R P. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(5):987–1004. doi: 10.1111/jan.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Finan L.J., Bersamin M., Fisher D.A. Sexual orientation-based depression and suicidality health disparities: The protective role of school-based health centers. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal Of The Society For Research On Adolescence. 2018 doi: 10.1111/jora.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.