Abstract

Racism has been declared a public health crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted inequities in the US health care system and presents unique opportunities for the pharmacy Academy to evaluate the training of student pharmacists to address social determinants of health among racial and ethnic minorities. The social ecological model, consisting of five levels of intervention (individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy) has been effectively utilized in public health practice to influence behavior change that positively impacts health outcomes. This paper adapted the social ecological model and proposed a framework with five intervention levels for integrating racism as a social determinant of health into pharmacy curricula. The proposed corresponding levels of intervention for pharmacy education are the curricular, interprofessional, institutional, community, and accreditation levels. Other health professions such as dentistry, medicine, and nursing can easily adopt this framework for teaching racism and social determinants of health within their respective curricula.

Keywords: racial and ethnic minorities, structural racism, social determinants of health, pharmacy education

INTRODUCTION

As the United States population continues to grow and minority populations grow at a faster rate, racial inequity, social injustice, and structural racism have become more apparent and racism has been declared a public health crisis.1 Therefore, it is paramount that student pharmacists understand the influences of racism on health and wellness outcomes and health care delivery so that they may: address the unequal distribution of social determinants of health (SDOH) that are key drivers of health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations; and engage in efforts to dismantle systemic racism and facilitate systemic changes.

Diaz-Cruz and colleagues2 urged pharmacy programs to continue to explore novel instructional methodologies that prepare graduates to provide access to quality health care and advocate for public health interventions that decrease health care disparities at interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy levels. Kiles and colleagues3 encouraged pharmacy schools to integrate all domains of SDOH throughout pharmacy curricula using the “socioecological approach”; they did not provide a framework for their proposal. To address these identified gaps in the literature, the purpose of this review is to propose a conceptual framework for integration of SDOH among racial and ethnic minorities in the pharmacy curricula using the social ecological model.

Conceptual Framework

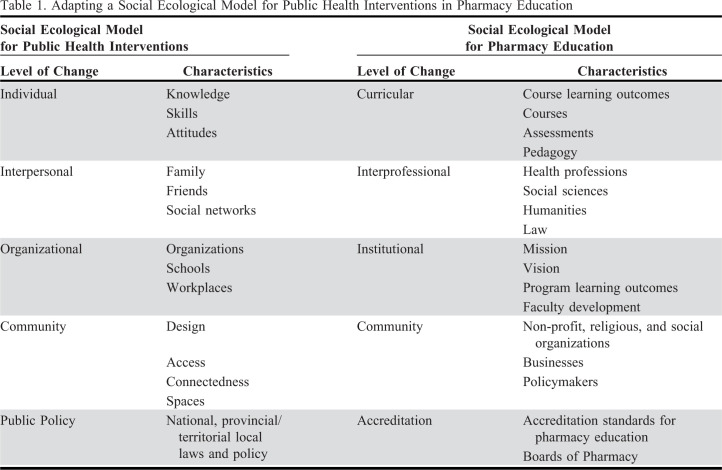

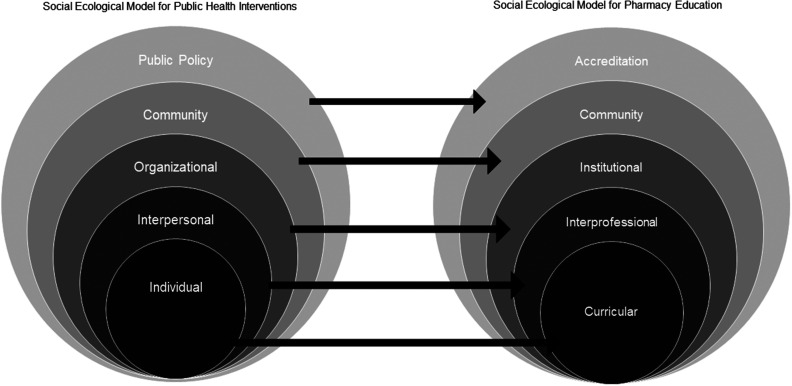

The social ecological model is used in public health to influence health outcomes and effect behavior change.4 Its five intervention levels target individual/intrapersonal factors, interpersonal processes and primary groups, institutional factors, community factors, and public policy (Table 1). We adapted those five levels of the social ecological model and developed a framework with domains specific to pharmacy education (Table 1, Figure 1) and proposed curricular strategies for training student pharmacists to address SDOH among racial and ethnic minorities.

Table 1.

Adapting a Social Ecological Model for Public Health Interventions in Pharmacy Education

Figure 1.

Adaptation of the social ecological model for pharmacy education.4

The social ecological model (SEM) for public health consists of five levels to which interventions can target and effect behavior change: individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy. These five levels of the SEM have been adapted into domains that are specific to pharmacy education above. These are the domains in which interventions can effect change across the pharmacy academy. The curricula of colleges and schools of pharmacy embody the individual level. Just as interpersonal relationships can influence individuals, the interprofessional domain represents the interpersonal level whereby departments, schools, and colleges can collaborate and exert influence across disciplines. The institutional domain characterizes the organizational level, and the community level remains the same in both models. Finally, the accreditation domain symbolizes public policy for pharmacy education.

Curricular Strategy 1: Pharmacy faculty should horizontally and vertically integrate educational content on structural racism and its effects on health and wellness outcomes into the didactic and experiential components of pharmacy curricula. Literature in medical, pharmacy, and other health professional programs demonstrates teaching and learning methods used to incorporate and assess SDOH, and educational strategies for increasing cultural competency and reducing health disparities.3,5,6 Similarly, pharmacy faculty should develop courses with content and learning outcomes that revolve around historical racial trauma and the impacts of racism (structural, institutional, internalized, and individual) on health.7

Formative assessments including small group discussions, reflections, research concept papers, concept maps, and the requirement that at least one introductory or advanced pharmacy practice experience be completed in an underserved racial/ethnic minority community are strongly recommended.3,5,6 One review article noted the use of students’ clinical rotations as immersion experiences to acquire cultural knowledge and facilitate the application of culturally competent care.6 Faculty should develop corresponding assessment measures and longitudinal assessment plans for such curricular outcomes. As systemic oppression spans more than 400 years within the nation’s history, several teaching methods and integrated, longitudinal, multifaceted approaches are needed to deconstruct structural racism and its effects on health. This will aid students in developing increased awareness through cultural humility and deeper understanding of the effects of structural racism on SDOH.

Curricular Strategy 2: Pharmacy faculty should incorporate antiracist pedagogy into teaching methods. Blakeney8 defined antiracist pedagogy as a paradigm that is used to explain and thwart the enduring impact of racism. Antiracist pedagogy should: provide for understanding the effects of race and cultural differences on inequities in opportunity and social mobility;8-10 allow for critical consciousness, whereby students will develop deeper understandings of personal assumptions and biases regarding conditions of injustice in the world, thereby fostering a reorientation of perspective towards a commitment to social justice;10 address the social, cultural, and historical contexts which have created inequities;8-10 contain instruction that overtly confronts racism while allowing students to engage in discussions within inclusive, safe spaces;8-10 aim to impart race consciousness, and openly recognize the impact of race and racism in social contexts;11 aim to impart transformative learning through cognitive disequilibrium, which encourages students to understand and interrogate their implicit biases, positions of power, and privilege, and ultimately challenge the individual and structural systems that perpetuate racism;10 aim to impart structural competency to enable students in discerning how a host of clinical, social, and behavioral issues can also portray downstream effects of a number of upstream resolutions and policies about health care and food delivery systems, zoning laws, urban and rural infrastructures, medicalization, or definitions of illness and health.12

The incorporation of antiracist pedagogy into pharmacy education has the potential to impart a racial equity lens and equity-focused skill set to student pharmacists. It can create “outcomes of social justice,” that openly acknowledge the dignity and autonomy of, and delivery of high-quality pharmaceutical care to, racial and ethnic minorities regardless of gender, religion, sexual orientation, language, geographic origin, or socioeconomic background.8-10

Curricular Strategy 3: Pharmacy faculty should address what Sharma and colleagues10 describe as “the hidden curriculum” that maintains systems of oppression and undermines racial health equity through pharmacy Academy attitudes, practices, beliefs, behaviors, norms, or training. Vyas and colleagues13 report race-adjusted algorithms used in medicine that may perpetuate racial inequity. For example, racialized calculation of estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) yields higher eGFR values in Black patients, yet Black patients have disproportionately higher rates of end-stage renal disease.13 However, as Brottman and colleagues6 report, educators are inadequately prepared to teach diversity in relation to these and other political, socioeconomic, and geographical impacts on health compared to science-related subject content. Pharmacy faculty should understand the social, environmental, and political contextual factors that maintain race and ethnicity as risk factors for many chronic illnesses and educate student pharmacists on the underlying causes and structural consequences.

Interprofessional Strategy 1: The curricula of schools and colleges of pharmacy should provide interdisciplinary opportunities for student pharmacists to learn with and from students at other professional schools and graduate divisions about racial and ethnic minority communities, and to intentionally serve racial and ethnic minority communities, depending on collaborative curricula objectives. Hager and colleagues14 describe an interprofessional case-based activity between pharmacy and medical students regarding opioid abuse. Participants endorsed greater understanding of the role of SDOH, value of interprofessional collaboration, and a significant increase in the ability to learn with, from, and about interprofessional team members to develop a patient care plan.14 Addressing structural racism in health through SDOH requires interprofessional perspectives, through which students can develop critical and race consciousness.

Sabato and colleagues15 described a two-year longitudinal IPE course involving allied health, dentistry, medicine, nursing, public health, and graduate studies students. In year-one, teams of students met monthly to develop team-building, motivational interviewing, and communication skills.15 They participated in a Health Partner program, collaborating with the community to learn about their health care goals and experiences, and about their access to resources.15 In the second year, the teams analyzed and managed cases with complex health issues in a collaborative and discipline-specific, application-based manner.15 Incorporation of students from humanities, law, and social science disciplines (and their historical, political, and social perspectives) into similar intentional service-learning opportunities in racial and ethnic minority communities would expand opportunities to implement critical race theory concepts (“an emerging transdisciplinary, race-equity methodology grounded in social justice,”11 including race consciousness).

Institutional Strategy 2: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should structure their mission, vision, and programmatic learning outcomes to reflect a commitment to reducing health disparities in racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse populations, and to preparing future pharmacists who can understand and meet the needs of said populations. Doobay-Persaud and colleagues5 noted that faculty members have variable expertise in teaching SDOH. Further, Brottman and colleagues6 reported that the majority of educators that deliver diversity and inclusion education have interest in the subject matter, but lack adequate training in the area. Although these faculty should be trained, only a few studies described how to actually train them. As such, a key example of institutional commitment to training future pharmacists to plan, implement, and evaluate interventions to reduce racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic health disparities should include the commitment to provide appropriate faculty development and assessment in this arena. Thus, we recommend including implicit bias training and workshops on antiracist pedagogy as constant and integral components of the faculty development plan. Pharmacy educators should also consistently interrogate their personal positions of power and privilege.

Community Strategy 1: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should develop collaborative partnerships with social and religious organizations, businesses, and policymakers that serve as gatekeepers to racial and ethnic minority communities. Community engagement is necessary for students to translate theory into practice. It imbues students with cultural humility and allows for healing of historical racial trauma and injustices within the community. Schroeder and colleagues developed a course in which nursing students partnered with a socioeconomically disadvantaged community with high disease burden and health disparities.16 The students were assigned faculty and community mentors (gatekeepers), which included a wide array of professionals, including nonprofit leaders and public health professionals, chosen for their knowledge of the community, site needs, and resources, and their willingness and ability to serve as mentors.16 Participants worked on health promotion projects based on the identified needs of their assigned community.16 They also participated in online discussion boards and sessions on topics including the opioid epidemic and racism.16 An increased percentage of course participants rated their knowledge about “recognizing social determinants of health and understanding their effects on health outcomes and wellness” as very good or excellent on the post-course assessment (p ≤ .01).16 Additionally, a greater percentage of participants self-rated as confident or very confident in comparison to those who self-rated as somewhat confident, average confidence, or not confident with regard to: “recognizing the social determinants of health and applying them to assessment of patients with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds”, and “improving communication skills and developing effective relationships with patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds” (p < .01).16

The findings of Schroeder and colleagues provide support for our recommendations that collaborative partnerships should include community gatekeepers as guest lecturers and speakers in didactic courses and cocurricular activities, respectively; as partners in the development, delivery, and assessment of student pharmacists’ introductory and advanced practice experiences; as collaborators on community-based participatory research endeavors; and as members of board of trustees/visitors so that community engagement iteratively becomes community-academic partnership.5,17 For example, partnering with a nonprofit organization with access to a mobile health unit will likely increase racial and ethnic minority residents’ access to vaccines and allow pharmacy faculty to plant seeds for transformative learning through community engagement.

Accreditation Strategy 1: The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education should revise the “Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy” to include explicit key elements regarding structural racism. The concepts of SDOH, cultural competency, health disparities, diversity, and inclusion are undoubtedly related to structural racism. The accreditation bodies for other health professional education, including medicine and dentistry have endorsed the inclusion of SDOH in their respective curriculums.6,18 Yet, there is no explicit mention of structural racism and how to address its impact on health and wellness outcomes in the health professions education accreditation milieu. Thus, the authors propose the following revision to the Accreditation Council of Pharmacy Education Standard 3, Key Element 3.5: The graduate is able to “recognize the impact of structural racism on the social determinants of health in order to diminish disparities and inequities in access to quality care.”19 If such a policy change is put into action, then and only then may we finally advance health equity in earnest.

SUMMARY

The authors adapted the social ecological model to conceptualize an innovative approach in pharmacy education for addressing racism as a SDOH so that we may ultimately overcome social injustice. The strategies include: curricular integration of structural racism as a root cause of an unequal distribution of SDOH; approach to practice and care that includes IPE activities; revision of institutional missions and visions to include language for the dismantling of structural racism and social injustice; community partnership with policy and law makers and engagement with local community organizations; and inclusion of structural racism and social justice in the accreditation and re-accreditation standards for pharmacy education. Future research is necessary to explore the roles that Boards of Pharmacy could play in incorporating the concepts of SDOH and racism into pharmacy licensing examinations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, Gilbert KL. Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional. Part I: Is racism a public health issue? American Public Health Association (APHA) Press, Washington, DC. 2019 January;9-13. 10.2105/9780875533049partl. [DOI]

- 2.Diaz-Cruz ES. If cultural sensitivity is not enough to reduce health disparities, what will pharmacy education do next? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11:538-540. 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiles T, Jasmin H, Nichols B, Haddad R, Renfro CP. A scoping review of active learning strategies for teaching social determinants of health in pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(11):1482-1490. 10.5688/ajpe8241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golden SD, Earp JL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education and behavioral health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior. 2012;39(3):364-372. doi: 10.1177/1090198111418634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doobay-Persaud A, Adler MD, Bartell TR, et al. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education. A scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;16;34(5):720-730. 10.1007/s11606-019-04876-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brottman MR, Char DM, Hattori RA, Heeb R, Taff SD. Toward cultural competency in health care: a scoping review of the diversity and inclusion education literature. Acad Med. 2020;95(5). doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arya V, Butler L, Leal S, et al. Structural racism: pharmacists’ role and responsibility. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(11):8418.. 10.5688/ajpe8418; J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(6):e43-46. ; J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(7):1265-1268. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakeney AM. Antiracist pedagogy: definition, theory, and professional development. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy. 2011;119-132. 10.1080/15505170.2005.10411532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma M, Pinto A, Kumagai A. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med . 2019;93(1):25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: towards antiracism praxis. Am J Pub Health. 2010;100(S1):S30-S35. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058. Accessed February 8, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vyas DA, Einstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight – reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:874-882. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2004740. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMms2004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hager KD, Blue HL, Zhang L, Palombi LC. Opioids: cultivating interprofessional collaboration to find solutions to public health problems. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(1):120-124. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1516634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabato E, Owens J, Mauro AM, Findley P, Lamba S, Fenesy K. Integrating social determinants of health in dental curricula: an interprofessional approach. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(3):237-245. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder K, Garcia B, Snyder Phillips R, Lipman TH. Assessing social determinants of health through community engagement: an undergraduate nursing course. J Nurs Educ . 2019;58(7):423-426. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20190614-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt J, Bonham C, Jones L. Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2011;86:246-251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182046481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid CA, Evanson TA. Using simulation to teach about poverty in nursing education: a review of available tools. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32(2):130-140. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree (“Standards 2016”). Chicago, IL; 2015. https://www.acpeaccredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.