Abstract

Flaviviruses are zoonotic pathogens transmitted by the bite of infected mosquitos and ticks and represent a constant burden to human health. Here we review recent literature aimed at uncovering how flaviviruses interact with the cells that they infect. A better understanding of these interactions may ultimately lead to novel therapeutic targets. We highlight several studies that employed low-biased methods to discover new protein–protein, protein–RNA, and genetic interactions, and spotlight recent work characterizing the host protein, TMEM41B, which has been shown to be critical for infection by diverse flaviviruses and coronaviruses.

Current Opinion in Virology 2022, 52:71–77

This review comes from a themed issue on Viral pathogenesis

Edited by Michaela Gack and Susan Baker

For complete overview about the section, refer Viral Pathogenesis (2022)

Available online 9th December 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2021.11.007

1879-6257/© 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Flaviviruses and their worldwide importance

Flaviviruses are a family of positive-strand RNA viruses that includes important human pathogens such as Zika (ZIKV), yellow fever (YFV), dengue (DENV), West Nile (WNV), Japanese encephalitis (JEV), Powassan (POWV) and tick-borne encephalitis (TBEV) viruses. Together, these viruses contribute to staggering numbers of human infections and deaths each year [1]. Flaviviruses are usually transmitted through arthropod vectors and dissemination is therefore influenced by climate and geography. Increased human population densities, human movement, and the expanding range for ticks and mosquitoes due to rising global temperatures associated with climate change have contributed to increased numbers of epidemics in new geographical locations [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

Successful vaccines have been developed for the prevention of YFV, JEV, and TBEV infection, but none are available for other pathogenic flaviviruses. Moreover, there are currently no approved drugs available for the specific treatment of any flaviviral disease; however, a promising small molecule pan-DENV candidate was recently described [7•]. An alternative approach to developing anti-flaviviral therapies is to disrupt critical interactions that occur between host factors and viral proteins or RNAs.

Host factors can be cellular proteins, RNAs, lipids, sugars, or small molecules, and they can be discovered by direct or indirect physical interactions with viral RNA or proteins or through genetic interactions by perturbing the host. As existing techniques improve and new technologies are developed, a steady stream of new virus–host interactions continues to be uncovered. In this short review, we highlight some of the papers published in the past two to three years that used low-biased methods to identify flavivirus–host interactions. We then spotlight one host factor, transmembrane protein 41b (TMEM41B), where a variety of recent studies collectively shed light on how this protein, which has a reported role in autophagy, may facilitate the formation of flavivirus RNA replication organelles (ROs).

Low-biased approaches to identify flavivirus host factors

Protein–protein interactions

Affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) is one low-biased approach to identify virus–host protein–protein interactions. This often entails engineering affinity purification tags on viral protein(s) of interest, ideally, in the context of the viral genome. This is challenging for flaviviruses since all viral proteins are produced as a single long polypeptide chain, and affinity purification tags can interfere with polyprotein processing by virus and host proteases and protein function. Consequently, most flavivirus AP-MS studies rely on overexpression of individual affinity-tagged viral proteins (which can affect localization and protein–protein interactions), and results can vary depending on the design of expression constructs and purification conditions. Many flavivirus proteins are also intimately associated with membranes, which poses additional challenges for retaining protein–protein interactions during sample preparation. Despite these caveats, researchers have employed this strategy to identify bona fide flavivirus host factors [8,9,10•,11,12].

A recent review describes several flavivirus host factors and pathways identified in large-scale AP-MS screens [13•]. Here we highlight select host factors identified in recent screens performed in human cells with known roles in autophagy. Subsequently, we review several studies performed in mosquito and tick cells. Among 386 ZIKV interactors identified by Scaturro et al. in human SK-N-BE2 cells, TMEM41B was found to interact specifically with ZIKV NS4B, a viral transmembrane protein involved in forming ROs [10•]. TMEM41B has since been shown to be important for early stages of autophagy [14,15•,16,17]. Further, Scaturro et al. also performed a global phospho-proteomics analysis in uninfected and ZIKV-infected cells and uncovered differential regulation of several signaling pathways including downregulation of AKT-mTOR signaling in ZIKV-infected cells and increased phosphorylation of DAP, a negative regulator of autophagy. This is consistent with an upregulation of autophagy previously observed in ZIKV-infected cells [18]. In addition to these observations, Shah et al. identified an interaction between DENV NS4B and p62/SQSTM1 [11]. SQSTM1 is also involved in autophagy and was previously shown to be functionally relevant for flavivirus infection [19,20]. Additional work is required to determine whether autophagy itself is important for flavivirus infection or whether proteins involved in autophagy are hijacked simply to remodel membranes and establish ROs [21•,22].

Since flaviviruses persist in arthropod vectors it is also important to understand how host factor interactions overlap or differ between vector and host species. This information could reveal essential interactions shared across diverse hosts and/or cellular factors that can be targeted in vector species to reduce virus dissemination. While progress has been made [23,24], genome annotations for tick species are still incomplete making MS-based methods of host factor discovery difficult. However, Lemasson et al. [25] recently reported a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H)-based screen to identify protein–protein interactions of TBEV and louping ill virus (LIV) proteins in tick cells. Here, all TBEV and LIV proteins were screened against a cDNA library generated from Ixodes ricinus-derived cell lines. The authors identified interactions with multiple proteins implicated in signal transduction, protein degradation, and cytoskeletal function. Interestingly, the viral NS5 and prM proteins appeared to interact with several tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor (TRAF) proteins, which may facilitate viral persistence in ticks and promote viral transmission to mammalian hosts.

For the mosquito vector, Shah et al. [11] also reported a DENV interactome using Aag2 cells, and Marin-Lopez et al. [26] performed MS on purified DENV particles incubated with salivary glands extracted from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The authors of the latter study identified 45 salivary gland proteins that potentially interact with DENV virions. Two proteins (AAEL006582 and AAEL004559) were further evaluated in vitro and in vivo and found to regulate viral burden. AAEL006582 is a calcium transporter ATPase protein that may play a role in the secretory pathway, and AAEL004559 belongs to the synaptosomal-associated protein (SNAP) family, which is implicated in endocytic and exocytic trafficking, vesicle fusion, and autophagy. These studies and others [27] have become increasingly feasible as Aedes aegypti genome annotations continue to improve [28].

Protein–RNA interactions

The ∼11 kb positive-sense single-stranded genomic RNA found in virions serves as a messenger RNA which gives rise to all flavivirus proteins and alone is sufficient to initiate infection. Once sufficient viral proteins are produced and ROs are formed, this same RNA molecule transitions to become the template for minus-strand RNA synthesis, which is the template for making more plus strands that yield more viral proteins, and ultimately, new virus particles.

Several groups have taken a low-biased RNA-centric approach to identify host proteins that interact directly or indirectly with flavivirus RNA. In 2016 two groups utilized UV light to covalently crosslink DENV RNA to proteins, followed by denaturation and DENV RNA capture using antisense oligos [29,30]. More recently, a similar approach by Ooi et al. named ChIRP-MS (comprehensive identification of RNA-binding proteins by mass spectrometry) was employed to capture proteins associated with ZIKV and DENV RNA [31••]. A major difference between this method and the previous reports is the use of formaldehyde chemical crosslinking rather than UV-crosslinking. While UV-crosslinking is specific for direct protein–RNA interactions, formaldehyde crosslinking forms covalent protein–RNA and protein–protein crosslinks facilitating the recovery of larger complexes. This may preserve information about the context in which protein–RNA interactions occur. In comparison to the UV-crosslinking studies which identified 12 and 93 protein interactors, respectively [29,30], the ChIRP-MS method identified 494 proteins that the authors categorized as high confidence interactors. Although the list is large, it is encouraging that 75% of the hits have known or predicted RNA binding domains and proteins that localize to the ER, where the viral RNA is replicated, translated, and packaged into new virions.

To prioritize candidates for further characterization, Ooi et al., integrated their list of ChIRP-MS host factors with previously published genome-wide knockout screen data sets along with their results from additional screens [31••]. This analysis highlighted the overlap between known host factor complexes such as the OST complex, and identified Vigilin (aka, high-density lipoprotein-binding protein; HDLBP) and RRBP1 (ribosome binding protein 1) as two host factors required for flavivirus infection. While the mechanisms await further elucidation, the studies described in the paper indicate that RRBP1 and Vigilin promote the translation, replication, and stability of flavivirus RNA.

The studies described above focused on the replication stage of infection. In future studies, it may also be interesting to interrogate the earliest protein interactions of the incoming viral RNA using alternative crosslinking methods such as the recently described VIR-CLASP (viral cross-linking and solid-phase purification) method used to identify host factors that associate with the pre-replicated chikungunya virus genome [32].

Single-cell RNA-seq

Correlating gene expression with virus infection is another powerful, low-biased approach to gaining insights into virus–host interactions. In recent work by Zanini et al. [33••], the authors performed single-cell RNA-seq on DENV-infected and ZIKV-infected cells, then capitalized on the high degree of heterogeneity in gene expression and virus replication naturally present in cell populations to identify candidate proviral and antiviral genes. Their approach, which they termed viscRNA-Seq (virus-inclusive single cell RNA-Seq), entails a modified library preparation that includes virus-specific oligos to capture viral RNAs in addition to oligo-dT to capture polyadenylated cellular mRNAs. In doing so, the authors identified cells with a wide range of viral RNA abundance. This information was used to draw a correlation or anti-correlation with cellular mRNA abundance. The prediction was that genes whose abundance correlated with viral RNA may have a proviral role, whereas genes whose abundance was anti-correlated may have an antiviral role.

Several genes whose mRNA abundance correlated with viral RNA were previously identified in genome-wide CRISPR KO screens as proviral host factors, thereby providing confidence in the approach [19,34]. The authors then used siRNA knockdown to demonstrate that other potentially pro-DENV factors including components of the ER translocon (RPL31 and TRAM1) and proteins involved in membrane trafficking (TMED2, COPE, HSPA5, and DDIT3) were indeed important for virus infection. Some of these host factors were also found to increase viral infection when overexpressed as cDNAs, indicating that their abundance may be rate-limiting. Similar experiments were performed for potential anti-viral host factors and the authors found that knocking down ID2 and CTTNB1 (B-catenin) increased DENV infection indicating that these genes may indeed have an antiviral role. Interestingly, the authors also identified several genes that displayed a more complicated relationship with virus infection over time—for example, some genes initially correlated with viral abundance and then anticorrelated, and vice versa. The authors speculate that these host factors may promote the accumulation of viral RNA at one stage of the life cycle and limit it at another. In summary, this RNA-seq approach identified additional flavivirus host factors and uncovered several potentially important differences between ZIKV and DENV. It may be interesting to couple the viscRNA-Seq approach with pooled CRISPR activation or inhibition methods to further perturb gene expression and determine the effect that induced changes to host gene expression have on flavivirus infection.

Genetic screens

In recent years, pooled CRISPR KO screens have proven to be a powerful and accessible genome-scale approach to identify proviral host factors. Typically, a population of KO cells is infected, the virus spreads through the culture killing cells, and the surviving cells are collected for analysis. Some limitations to this approach are that genes essential for cell growth or survival cannot be interrogated and screens are biased towards identifying host factors required during the early stages of the virus infection. Nevertheless, one advantage of this method is that it inherently includes a functional readout.

Numerous flavivirus screens from multiple labs have used this approach to identify critical flavivirus host factors including, among others, STT3A/B involved in oligosaccharide transfer, SSR1/2/3 involved in protein translocation into the ER, and ER membrane complex (EMC) subunits, which facilitate folding of transmembrane proteins [19,34,35]. Recently, Ngo et al. [36] further characterized the role of the EMC in flavivirus infection and found that this complex is essential for the proper topology of flavivirus transmembrane proteins NS4A and NS4B [36].

In addition, recent CRISPR KO screens have been published including a genome-wide screen with ZIKV performed in human stem cells differentiated into neural progenitor cells [37], a ZIKV screen in Huh-7.5 cells [38•], and screens with ZIKV and YFV in HAP1 cells [21•]. Highlights from these reports include mechanistic follow-up where Shue et al. show that RACK1 is required for multiple mosquito-borne and tick-borne flaviviruses as well as the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 [38•]. The results indicate that RACK1 may be involved in establishing ROs on the ER membrane. Work from Hoffmann et al., focused on TMEM41B, which, like RACK1, was found to also be required by multiple mosquito-borne and tick-borne flaviviruses as well as multiple coronaviruses [39] and is likely important for establishing ROs.

Like MS-based methods, the ability to perform low-biased functional genomics screens in vector species requires reasonably well annotated genomic information. This, together with fewer options for delivering screening machinery (e.g., Cas9 and sgRNAs) to mosquito and tick cells, has limited similar studies in these cell types. Nevertheless, CRISPR-Cas9 systems are established in mosquito cells and larger-scale screens are within reach [40, 41, 42].

TMEM41B — a critical host factor for membrane remodeling

Here we highlight the host factor, TMEM41B, which is involved in autophagy and is critical not only for flaviviruses, but also coronaviruses. TMEM41B was first identified as a potential DENV host factor when it appeared as a hit in a genome-wide CRISPR KO screen [19]. Subsequently, Scaturro et al. identified TMEM41B as a ZIKV NS4B interacting partner and verified that it was indeed important for flavivirus infection [10•]. Aside from this, little was known about the cellular function of TMEM41B until within a short time frame three independently reported CRISPR KO screens identified TMEM41B as a critical regulator of autophagy [14,15•,17]. In our recent publications [21•,39], we show that TMEM41B is an essential host factor for diverse members of both the Flaviviridae and Coronaviridae. We found that TMEM41B is also required for multiple flaviviruses in the mosquito vector and, that autophagy per se is not required for flavivirus infection [21•]. Additional studies corroborate these findings and solidly establish TMEM41B as a bona fide host factor that is broadly required for these two virus families [21•,22,39,43,44].

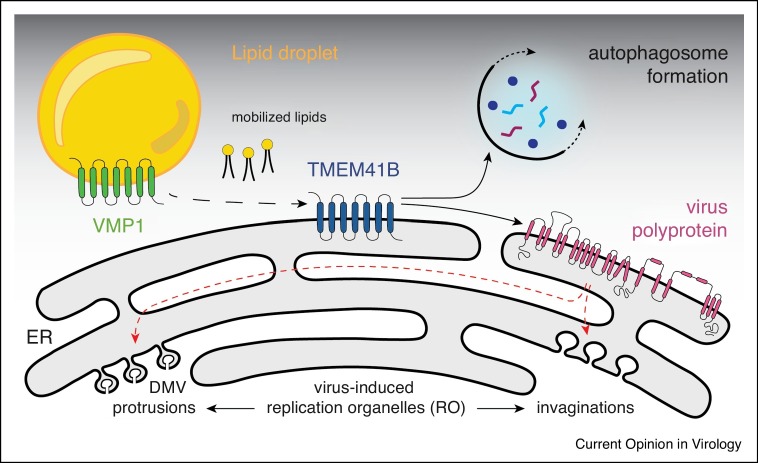

Growing evidence indicates that TMEM41B and a related protein, VMP1, act at the early stages of autophagosome formation, possibly mobilizing lipids in the ER to facilitate membrane curvature [14,15•,16,17,45,46]. Indeed, several groups have shown that both proteins act as phospholipid scramblases capable of flipping lipids between leaflets of lipid bilayers [47,48•,49, 50, 51]. It is possible that flaviviruses and coronaviruses hijack this function to form ROs on ER membranes by recruiting one or both proteins through direct protein–protein interaction. It is also possible that co-localization of TMEM41B with ROs occurs through passive diffusion, where, by mobilizing neutral and sterol lipids, TMEM41B helps lower the local free energy imposed by viral protein-induced membrane curvature. A model of TMEM41B’s role in cellular and viral membrane remodeling processes is depicted in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

A model of TMEM41B’s role in cellular and viral membrane remodeling processes.

Transmembrane protein 41B (TMEM41B) and vacuole membrane protein 1 (VMP1) interact and function as lipid scramblases facilitating membrane expansion and organelle biogenesis needed for the formation of autophagosomes. Upon flavivirus infection the viral polyprotein is folded into the ER membrane and processed by host and viral proteases. TMEM41B is recruited by viral proteins, and its scramblase function is redirected to facilitate membrane remodeling to form replication organelles (RO). ROs can be grouped into two morphologically distinct classes designated as double membrane vesicles (DMV) or protrusion-type ROs and invaginated/spherule-type ROs. While DENV and ZIKV induce invaginated ROs [52,53], HCV induces protrusion-like ROs [54]. Similar DMV structures derived from various organelles have been found in cells infected with other (+) sense RNA viruses, for example, picornaviruses [55,56], noroviruses [57], arterivirus [58] and coronaviruses [59, 60, 61, 62, 63].

Several observations related to TMEM41B’s role as a flavivirus host factor remain unexplained. For example, there is variability in the requirement for TMEM41B among cell types and viruses, and single amino acid mutations in NS4A/B are sufficient for ZIKV and YFV to replicate in TMEM41B KO cells [21•]. Can these observations be explained by redundancy in TMEM41B activity (e.g., compensation by VMP1)? Most importantly, can TMEM41B’s role in autophagy and lipid homeostasis be separated from its proviral role in flavivirus and coronavirus infection? Answering these questions will be critical for deciding whether targeting TMEM41B is a viable antiviral strategy.

Future outlook

Unsurprisingly, most host factor studies to date have been performed in mammalian cells. However, flaviviruses have evolved to persist in vector species and characterizing host factor interactions in vector species represents a new frontier for future studies. With new mosquito and tick genomes being sequenced and gene annotations improving, discovering host factor interactions in these species is becoming increasingly feasible. Discovery, however, is only the beginning, and obtaining mechanistic insight will continue to be essential to advance the field. As exemplified by the brief review of TMEM41B, this often requires a variety of techniques and expertise from diverse fields to gain new insights. With new discoveries to be made and even more mechanistic details to be sorted out, the field of flavivirus–host interactions is sure to remain an exciting area of investigation for the foreseeable future.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We thank Alison W. Ashbrook, Margaret R. MacDonald, Michael Bauer, and Michael G. Grodus for critical feedback, and we thank Charles M. Rice for providing us with this opportunity. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI124690 (to C. M. Rice). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor does it represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Gould E.A., Solomon T. Pathogenic flaviviruses. Lancet. 2008;371:500–509. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60238-X. Epub 2008/02/12. PubMed PMID: 18262042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady O.J., Hay S.I. The global expansion of dengue: how Aedes aegypti mosquitoes enabled the first pandemic arbovirus. Annu Rev Entomol. 2020;65:191–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-024918. Epub 2019/10/09. PubMed PMID: 31594415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugueras S., Fernandez-Martinez B., Martinez-de la Puente J., Figuerola J., Porro T.M., Rius C., et al. Environmental drivers, climate change and emergent diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and their vectors in southern Europe: a systematic review. Environ Res. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110038. Epub 2020/08/19. PubMed PMID: 32810503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobler G. Zoonotic tick-borne flaviviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.024. Epub 2009/09/22. PubMed PMID: 19765917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherson M., Garcia-Garcia A., Cuesta-Valero F.J., Beltrami H., Hansen-Ketchum P., MacDougall D., et al. Expansion of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada inferred from CMIP5 climate projections. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125 doi: 10.1289/EHP57. Epub 2017/06/10. PubMed PMID: 28599266; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5730520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medlock J.M., Hansford K.M., Bormane A., Derdakova M., Estrada-Pena A., George J.C., et al. Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-1. Epub 2013/01/04. PubMed PMID: 23281838; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3549795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Kaptein S.J.F., Goethals O., Kiemel D., Marchand A., Kesteleyn B., Bonfanti J.F., et al. A pan-serotype dengue virus inhibitor targeting the NS3-NS4B interaction. Nature. 2021;598:504–509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03990-6. Epub 2021/10/08. PubMed PMID: 34616043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reports a potent dengue virus inhibitor (JNJ-A07) that blocks interaction between viral NS3 and NS4B proteins and has activity against a variety of genotypes and serotypes.

- 8.Coyaud E., Ranadheera C., Cheng D., Goncalves J., Dyakov B.J.A., Laurent E.M.N., et al. Global interactomics uncovers extensive organellar targeting by Zika virus. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018;17:2242–2255. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR118.000800. Epub 2018/07/25. PubMed PMID: 30037810; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6210227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafirassou M.L., Meertens L., Umana-Diaz C., Labeau A., Dejarnac O., Bonnet-Madin L., et al. A global interactome map of the dengue virus NS1 identifies virus restriction and dependency host factors. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3900–3913. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.094. Epub 2017/12/28, PubMed PMID: 29281836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Scaturro P., Stukalov A., Haas D.A., Cortese M., Draganova K., Plaszczyca A., et al. An orthogonal proteomic survey uncovers novel Zika virus host factors. Nature. 2018;561:253–257. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0484-5. Epub 2018/09/05. PubMed PMID: 30177828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper used AP-MS and identified an interaction between the host protein TMEM41B and the ZIKV NS4B protein.

- 11.Shah P.S., Link N., Jang G.M., Sharp P.P., Zhu T., Swaney D.L., et al. Comparative flavivirus-host protein interaction mapping reveals mechanisms of dengue and Zika virus pathogenesis. Cell. 2018;175:1931–1945.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.028. Epub 2018/12/15. PubMed PMID: 30550790; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6474419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song G., Lee E.M., Pan J., Xu M., Rho H.S., Cheng Y., et al. An integrated systems biology approach identifies the proteasome as a critical host machinery for ZIKV and DENV replication. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2021;19:108–122. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2020.06.016. Epub 2021/02/22. PubMed PMID: 33610792; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8498969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Li M., Ramage H., Cherry S. Deciphering flavivirus-host interactions using quantitative proteomics. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;66:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.06.002. Epub 2020/07/19. PubMed PMID: 32682290; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7749055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper used AP-MS to identify ZIKV protein interacting partners in human cells and DENV protein interacting partners in both human and mosquito cells.

- 14.Moretti F., Bergman P., Dodgson S., Marcellin D., Claerr I., Goodwin J.M., et al. TMEM41B is a novel regulator of autophagy and lipid mobilization. EMBO Rep. 2018;19 doi: 10.15252/embr.201845889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Morita K., Hama Y., Izume T., Tamura N., Ueno T., Yamashita Y., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies TMEM41B as a gene required for autophagosome formation. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3817–3828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201804132. Epub 2018/08/11. PubMed PMID: 30093494; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6219718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Together with Moretti et al. and Shoemaker et al., this paper identified TMEM41B as a protein involved in early stages of autophagy.

- 16.Morita K., Hama Y., Mizushima N. TMEM41B functions with VMP1 in autophagosome formation. Autophagy. 2019;15:922–923. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1582952. Epub 2019/02/19. PubMed PMID: 30773971; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6526808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoemaker C.J., Huang T.Q., Weir N.R., Polyakov N.J., Schultz S.W., Denic V. CRISPR screening using an expanded toolkit of autophagy reporters identifies TMEM41B as a novel autophagy factor. PLoS Biol. 2019;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2007044. Epub 2019/04/02. PubMed PMID: 30933966; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6459555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Q., Luo Z., Zeng J., Chen W., Foo S.S., Lee S.A., et al. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate Akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.019. Epub 2016/08/16. PubMed PMID: 27524440; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5144538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marceau C.D., Puschnik A.S., Majzoub K., Ooi Y.S., Brewer S.M., Fuchs G., et al. Genetic dissection of Flaviviridae host factors through genome-scale CRISPR screens. Nature. 2016;535:159–163. doi: 10.1038/nature18631. Epub 2016/07/08. PubMed PMID: 27383987; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4964798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metz P., Chiramel A., Chatel-Chaix L., Alvisi G., Bankhead P., Mora-Rodriguez R., et al. Dengue virus inhibition of autophagic flux and dependency of viral replication on proteasomal degradation of the autophagy receptor p62. J Virol. 2015;89:8026–8041. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00787-15. Epub 2015/05/29. PubMed PMID: 26018155; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4505648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Hoffmann H.H., Schneider W.M., Rozen-Gagnon K., Miles L.A., Schuster F., Razooky B., et al. TMEM41B is a pan-flavivirus host factor. Cell. 2021;184:133–148.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.005. Epub 2020/12/19. PubMed PMID: 33338421; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7954666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper characterizes TMEM41B as a pan-flavivirus host factor.

- 22.Trimarco J.D., Heaton B.E., Chaparian R.R., Burke K.N., Binder R.A., Gray G.C., et al. TMEM41B is a host factor required for the replication of diverse coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009599. Epub 2021/05/28. PubMed PMID: 34043740; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8189496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulia-Nuss M., Nuss A.B., Meyer J.M., Sonenshine D.E., Roe R.M., Waterhouse R.M., et al. Genomic insights into the Ixodes scapularis tick vector of Lyme disease. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10507. Epub 2016/02/10. PubMed PMID: 26856261; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4748124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J.R., Koren S., Dilley K.A., Harkins D.M., Stockwell T.B., Shabman R.S., et al. A draft genome sequence for the Ixodes scapularis cell line, ISE6. F1000Res. 2018;7 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13635.1. Epub 2018/05/01. PubMed PMID: 29707202; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5883391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemasson M., Caignard G., Unterfinger Y., Attoui H., Bell-Sakyi L., Hirchaud E., et al. Exploration of binary protein-protein interactions between tick-borne flaviviruses and Ixodes ricinus. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14 doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-04651-3. Epub 2021/03/08. PubMed PMID: 33676573; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7937244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marin-Lopez A., Jiang J., Wang Y., Cao Y., MacNeil T., Hastings A.K., et al. Aedes aegypti SNAP and a calcium transporter ATPase influence dengue virus dissemination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009442. Epub 2021/06/12. PubMed PMID: 34115766; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8195420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gestuveo R.J., Royle J., Donald C.L., Lamont D.J., Hutchinson E.C., Merits A., et al. Analysis of Zika virus capsid-Aedes aegypti mosquito interactome reveals pro-viral host factors critical for establishing infection. Nat Commun. 2021;12 doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22966-8. Epub 2021/05/15. PubMed PMID: 33986255; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8119459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews B.J., Dudchenko O., Kingan S.B., Koren S., Antoshechkin I., Crawford J.E., et al. Improved reference genome of Aedes aegypti informs arbovirus vector control. Nature. 2018;563:501–507. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0692-z. Epub 2018/11/16. PubMed PMID: 30429615; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6421076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips S.L., Soderblom E.J., Bradrick S.S., Garcia-Blanco M.A. Identification of proteins bound to dengue viral RNA in vivo reveals new host proteins important for virus replication. mBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01865-15. Epub 2016/01/07. PubMed PMID: 26733069; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4725007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viktorovskaya O.V., Greco T.M., Cristea I.M., Thompson S.R. Identification of RNA binding proteins associated with dengue virus RNA in infected cells reveals temporally distinct host factor requirements. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004921. Epub 2016/08/25. PubMed PMID: 27556644; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4996428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Ooi Y.S., Majzoub K., Flynn R.A., Mata M.A., Diep J., Li J.K., et al. An RNA-centric dissection of host complexes controlling flavivirus infection. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:2369–2382. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0518-2. Epub 2019/08/07. PubMed PMID: 31384002; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6879806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identified hundreds of proteins that interact with DENV and ZIKV RNAs and nominate candidates with functional relevance by combining their interactome data sets with CRISPR screening results.

- 32.Kim B., Arcos S., Rothamel K., Jian J., Rose K.L., McDonald W.H., et al. Discovery of widespread host protein interactions with the pre-replicated genome of CHIKV using VIR-CLASP. Mol Cell. 2020;78:624–640.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.013. Epub 2020/05/08. PubMed PMID: 32380061; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7263428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33••.Zanini F., Pu S.Y., Bekerman E., Einav S., Quake S.R. Single-cell transcriptional dynamics of flavivirus infection. eLife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.32942. Epub 2018/02/17. PubMed PMID: 29451494; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5826272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using DENV and ZIKV, this paper demonstrates that single cell RNAseq, which captures natural variability in gene expression and viral RNA abundance within a cell population, can be used to identify proviral and antiviral host factors.

- 34.Zhang R., Miner J.J., Gorman M.J., Rausch K., Ramage H., White J.P., et al. A CRISPR screen defines a signal peptide processing pathway required by flaviviruses. Nature. 2016;535:164–168. doi: 10.1038/nature18625. Epub 2016/07/08. PubMed PMID: 27383988; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4945490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savidis G., McDougall W.M., Meraner P., Perreira J.M., Portmann J.M., Trincucci G., et al. Identification of Zika virus and dengue virus dependency factors using functional genomics. Cell Rep. 2016;16:232–246. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.028. Epub 2016/06/28. PubMed PMID: 27342126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngo A.M., Shurtleff M.J., Popova K.D., Kulsuptrakul J., Weissman J.S., Puschnik A.S. The ER membrane protein complex is required to ensure correct topology and stable expression of flavivirus polyproteins. eLife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.48469. Epub 2019/09/14. PubMed PMID: 31516121; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6756788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Muffat J., Omer Javed A., Keys H.R., Lungjangwa T., Bosch I., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen for Zika virus resistance in human neural cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:9527–9532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900867116. Epub 2019/04/26. PubMed PMID: 31019072; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6510995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38•.Shue B., Chiramel A.I., Cerikan B., To T.H., Frolich S., Pederson S.M., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies RACK1 as a critical host factor for flavivirus replication. J Virol. 2021;95 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00596-21. Epub 2021/09/30. PubMed PMID: 34586867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The paper demonstrates that RACK1 is critical for replication of multiple flaviviruses as well as the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

- 39.Schneider W.M., Luna J.M., Hoffmann H.H., Sanchez-Rivera F.J., Leal A.A., Ashbrook A.W., et al. Genome-scale identification of SARS-CoV-2 and pan-coronavirus host factor networks. Cell. 2021;184:120–132.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.006. Epub 2021/01/01. PubMed PMID: 33382968; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7796900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kistler K.E., Vosshall L.B., Matthews B.J. Genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9 in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Cell Rep. 2015;11:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.009. Epub 2015/03/31. PubMed PMID: 25818303; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4394034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu P., Jin B., Li X., Zhao Y., Gu J., Biedler J.K., et al. Nix is a male-determining factor in the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;118 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103311. Epub 2020/01/07. PubMed PMID: 31901476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozen-Gagnon K., Yi S., Jacobson E., Novack S., Rice C.M. A selectable, plasmid-based system to generate CRISPR/Cas9 gene edited and knock-in mosquito cell lines. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80436-5. Epub 2021/01/14. PubMed PMID: 33436886; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7804293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baggen J., Persoons L., Vanstreels E., Jansen S., Van Looveren D., Boeckx B., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies TMEM106B as a proviral host factor for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Genet. 2021;53:435–444. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00805-2. Epub 2021/03/10. PubMed PMID: 33686287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang R., Simoneau C.R., Kulsuptrakul J., Bouhaddou M., Travisano K.A., Hayashi J.M., et al. Genetic screens identify host factors for SARS-CoV-2 and common cold coronaviruses. Cell. 2021;184:106–119.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.004. Epub 2020/12/18. PubMed PMID: 33333024; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7723770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morishita H., Zhao Y.G., Tamura N., Nishimura T., Kanda Y., Sakamaki Y., et al. A critical role of VMP1 in lipoprotein secretion. eLife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.48834. Epub 2019/09/19. PubMed PMID: 31526472; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6748824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y.G., Chen Y., Miao G., Zhao H., Qu W., Li D., et al. The ER-localized transmembrane protein EPG-3/VMP1 regulates SERCA activity to control ER-isolation membrane contacts for autophagosome formation. Mol Cell. 2017;67:974–989.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.005. Epub 2017/09/12. PubMed PMID: 28890335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghanbarpour A., Valverde D.P., Melia T.J., Reinisch K.M. A model for a partnership of lipid transfer proteins and scramblases in membrane expansion and organelle biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101562118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Huang D., Xu B., Liu L., Wu L., Zhu Y., Ghanbarpour A., et al. TMEM41B acts as an ER scramblase required for lipoprotein biogenesis and lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1655–1670.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.006. Epub 2021/05/21. PubMed PMID: 34015269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper, together with Ghanbarpour et al., Lie et al., and Zhang et al., demonstrate that TMEM41B acts as an ER-localized lipid scramblase.

- 49.Li Y.E., Wang Y., Du X., Zhang T., Mak H.Y., Hancock S.E., et al. TMEM41B and VMP1 are scramblases and regulate the distribution of cholesterol and phosphatidylserine. J Cell Biol. 2021;220 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202103105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinisch K.M., Chen X.W., Melia T.J. “VTT”-domain proteins VMP1 and TMEM41B function in lipid homeostasis globally and locally as ER scramblases. Contact (Thousand Oaks) 2021;4 doi: 10.1177/25152564211024494. Epub 2021/08/28. PubMed PMID: 34447902; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8386813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang T., Li Y.E., Yuan Y., Du X., Wang Y., Dong X., et al. TMEM41B and VMP1 are phospholipid scramblases. Autophagy. 2021;17:2048–2050. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1937898. Epub 2021/06/03. PubMed PMID: 34074213; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8386743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortese M., Goellner S., Acosta E.G., Neufeldt C.J., Oleksiuk O., Lampe M., et al. Ultrastructural characterization of Zika virus replication factories. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2113–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.014. Epub 2017/03/02. PubMed PMID: 28249158; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5340982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welsch S., Miller S., Romero-Brey I., Merz A., Bleck C.K., Walther P., et al. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. Epub 2009/04/22. PubMed PMID: 19380115; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7103389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romero-Brey I., Merz A., Chiramel A., Lee J.Y., Chlanda P., Haselman U., et al. Three-dimensional architecture and biogenesis of membrane structures associated with hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003056. Epub 2012/12/14. PubMed PMID: 23236278; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3516559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belov G.A., Nair V., Hansen B.T., Hoyt F.H., Fischer E.R., Ehrenfeld E. Complex dynamic development of poliovirus membranous replication complexes. J Virol. 2012;86:302–312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05937-11. Epub 2011/11/11. PubMed PMID: 22072780; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3255921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Limpens R.W., van der Schaar H.M., Kumar D., Koster A.J., Snijder E.J., van Kuppeveld F.J., et al. The transformation of enterovirus replication structures: a three-dimensional study of single- and double-membrane compartments. mBio. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00166-11. Epub 2011/10/06. PubMed PMID: 21972238; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3187575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doerflinger S.Y., Cortese M., Romero-Brey I., Menne Z., Tubiana T., Schenk C., et al. Membrane alterations induced by nonstructural proteins of human norovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006705. Epub 2017/10/28. PubMed PMID: 29077760; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5678787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knoops K., Barcena M., Limpens R.W., Koster A.J., Mommaas A.M., Snijder E.J. Ultrastructural characterization of arterivirus replication structures: reshaping the endoplasmic reticulum to accommodate viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 2012;86:2474–2487. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06677-11. Epub 2011/12/23. PubMed PMID: 22190716; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3302280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gosert R., Kanjanahaluethai A., Egger D., Bienz K., Baker S.C. RNA replication of mouse hepatitis virus takes place at double-membrane vesicles. J Virol. 2002;76:3697–3708. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.8.3697-3708.2002. Epub 2002/03/22. PubMed PMID: 11907209; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC136101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klein S., Cortese M., Winter S.L., Wachsmuth-Melm M., Neufeldt C.J., Cerikan B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 structure and replication characterized by in situ cryo-electron tomography. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19619-7. Epub 2020/11/20. PubMed PMID: 33208793; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7676268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knoops K., Kikkert M., Worm S.H., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Koster A.J., et al. SARS-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060226. Epub 2008/09/19. PubMed PMID: 18798692; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2535663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maier H.J., Neuman B.W., Bickerton E., Keep S.M., Alrashedi H., Hall R., et al. Extensive coronavirus-induced membrane rearrangements are not a determinant of pathogenicity. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep27126. Epub 2016/06/04. PubMed PMID: 27255716; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4891661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W., Chen K., Zhang X., Guo C., Chen Y., Liu X. An integrated analysis of membrane remodeling during porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication and assembly. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200919. Epub 2018/07/25. PubMed PMID: 30040832; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6057628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]