Abstract

Objectives

To test the feasibility of using a new activity pacing framework to standardise healthcare professionals’ instructions of pacing, and explore whether measures of activity pacing/symptoms detected changes following treatment.

Design

Single-arm, repeated measures study.

Setting

One National Health Service (NHS) Pain Service in Northern England, UK.

Participants

Adult patients with chronic pain/fatigue, including chronic low back pain, chronic widespread pain, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Interventions

Six-week rehabilitation programme, standardised using the activity pacing framework.

Outcome measures

Feasibility was explored via patients’ recruitment/attrition rates, adherence and satisfaction, and healthcare professionals’ fidelity. Questionnaire data were collected from patients at the start and end of the programme (T1 and T2, respectively) and 3 months’ follow-up (T3). Questionnaires included measures of activity pacing, current/usual pain, physical/mental fatigue, depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, avoidance, physical/mental function and quality of life. Mean changes in activity pacing and symptoms between T1-T2, T2-T3 and T1-T3 were estimated.

Results

Of the 139 eligible patients, 107 patients consented (recruitment rate=77%); 65 patients completed T2 (T1-T2 attrition rate=39%), and 52 patients completed T3 (T1-T3 attrition rate=51%). At T2, patients’ satisfaction ratings averaged 9/10, and 89% attended ≥5 rehabilitation programme sessions. Activity pacing and all symptoms improved between T1 and T2, with smaller improvements maintained at T3.

Conclusion

The activity pacing framework was feasible to implement and patients’ ability to pace and manage their symptoms improved. Future work will employ a suitable comparison group and test the framework across wider settings to explore the effects of activity pacing in a randomised controlled trial.

Trial registration number

Keywords: pain management, rehabilitation medicine, musculoskeletal disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was the first study to test the feasibility of using a newly developed activity pacing framework in a rehabilitation programme to standardise the clinical instructions of activity pacing to patients with chronic pain/fatigue.

This feasibility study recruited to target with satisfactory recruitment/attrition rates.

A comprehensive measure of activity pacing: the 28-item Activity Pacing Questionnaire, and range of validated psychometric measures were suitable to detect changes before and after treatment.

This study was not powered with a control arm to determine treatment effectiveness.

The generalisability of this study is limited to a sample of predominantly females, of white ethnic origin, and from a single Pain Service.

Introduction

Activity pacing is a principal coping strategy for patients with long-term conditions, including chronic low back pain, chronic widespread pain, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME).1–5 Chronic pain and chronic fatigue are known to coexist,6 7 and overlap in symptoms, including depression, anxiety and disability.8–11 Conditions of chronic pain/fatigue may share similar disease processes: physical deconditioning following underactivity/avoidance, pathophysiological/psychological processes and central sensitisation.11–16 Treatments aim to reverse some of these processes: to improve physical/mental functioning, increase tolerance and improve quality of life.12 15 17 Recommended treatments include psychological therapies (eg, cognitive–behavioural therapy) and graded exposure to activity/exercise;15 16 of which activity pacing is a key component.18–20

Patients with chronic pain/fatigue may present with altered behaviours, including underactivity or avoidance of activities that are perceived as harmful or that may exacerbate symptoms; overactivity or excessive persistence to push through/distract from symptoms; or fluctuations between overactivity and underactivity.21 Activity pacing provides an alternative behaviour to enable patients to (re-)engage with activities in a manner that encourages their progression towards more regular or improved functioning.4 22 23

At present, there remains confusion regarding how activity pacing is defined or interpreted, and the effects on patients’ symptoms.5 24 25 There is no widely used guide to standardise how healthcare professionals instruct activity pacing to patients; and uncertainty whether different methods are required for symptoms of chronic pain versus chronic fatigue.3 26 This poses challenges how to advise patients with both chronic pain and fatigue.

We have developed an activity pacing framework using an inclusive approach for patients who present at rehabilitation services with chronic pain and/or fatigue. Using the Medical Research Council guidelines for developing complex interventions, mixed methods were implemented to encompass theoretical and stakeholder standpoints.27 Mixed methods comprise quantitative and qualitative approaches to collecting and analysing data.28 Stage I: Healthcare professionals’ survey gathered opinions on activity pacing (n=92).4 These findings, together with existing research formed the first draft of the framework and accompanying appendices. Stage II: Nominal group technique refined the activity pacing framework using a consensus meeting between patients and healthcare professionals (n=10).29 During the development of the activity pacing framework, stakeholders included healthcare professionals and patients with the aim of increasing the clinical utility and acceptability of the framework (see online supplemental figure 1 Content of the Activity Pacing Framework: Theory and Overview, and Appendices and Teaching Guide booklets.)

bmjopen-2020-045398supp001.pdf (196KB, pdf)

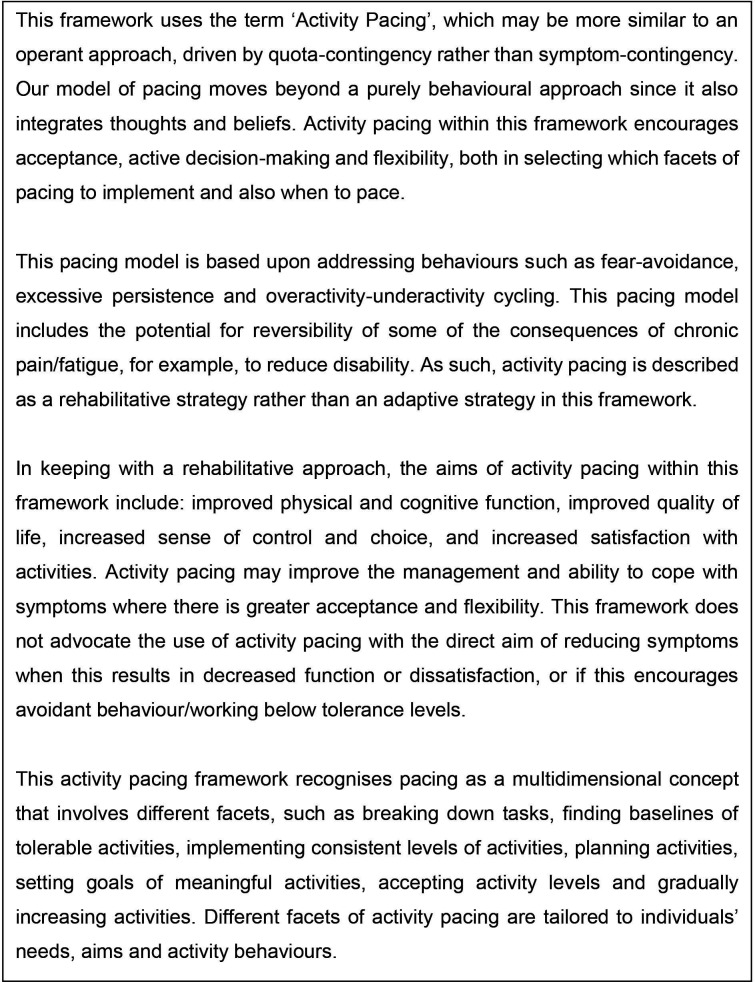

The conceptual model of the activity pacing framework (see figure 1) follows principles of quota-contingency and the operant approach (eg, setting goals according to time/distance/activity). The activity pacing framework is underpinned by concepts of rehabilitation with aims of improving physical and cognitive function; and engagement in, and satisfaction with meaningful activities, while managing symptoms.4 29 The activity pacing framework includes the potential for reversibility of some of the consequences of chronic pain/fatigue, such as the potential to reduce levels of disability. Together with containing themes of adjusting activities, planning and consistency, the activity pacing framework also includes themes of progression regarding the amount and/or variety of activities. Therefore, the activity pacing framework is considered to be a rehabilitative approach that moves forward from only adapting, or in some cases mal-adapting to the long-term condition. The activity pacing framework differs from energy conservation/adaptive pacing approaches which involve undertaking activities according to symptom severity (symptom-contingency) with an aim of reducing or avoiding symptoms.30 31 Within the current activity pacing framework, quota-contingency is advised alongside concepts of flexibility and choice to enable relevance and sustainability in conditions where symptoms may vary. The framework refers to all types of activities including work, household activities, cognitive activities, physical activities, exercise and relaxation to increase its wider relevance for patients with chronic pain and/or fatigue, for varying abilities and behaviours.

Figure 1.

Activity pacing conceptual model taken from the activity pacing framework.

The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of using the activity pacing framework to underpin a rehabilitation programme for chronic pain/fatigue. In preparation for a future clinical trial, specific objectives included: (1) Exploring participant recruitment/attrition rates and adherence/acceptability (for both chronic pain and fatigue); (2) Exploring healthcare professionals’ fidelity to the framework and (3) Exploring the suitability of the outcome measures, including the modified 28-item Activity Pacing Questionnaire (APQ-28).

Methods

Study design

This single-arm, repeated measures study is reported as a non-randomised feasibility study using the extended Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines,32 33 (see online supplemental table 1). Quantitative questionnaire data were collected from patients at the start (T1) and end (T2) of the 6-week rehabilitation programme, and at 3-month follow-up (T3). The study was prospectively registered (protocol available at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03497585). The acceptability of the framework, explored via interviews with patients and healthcare professionals, is reported elsewhere.34

Participant recruitment

Participants were identified from consecutive referrals to a rehabilitation programme for chronic pain/fatigue in a Pain Service in Northern England, UK. All patients attended a minimum of one face-to-face appointment before referral to the programme. Participants received the study information via the post 1 week before attending the programme and/or during the first session of the programme. The consent form was completed either at home or during the first session.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, with symptoms for ≥3 months and with a general practitioner or hospital consultant diagnosis of chronic low back pain, chronic widespread pain, fibromyalgia or CFS/ME. Patients were required to read and write in English. Ineligible patients were those with evidence of a serious underlying pathology, such as a current diagnosis of cancer, or patients with severe mental health or cognitive functioning issues.

Sample size

A sample size of 50 patients has been recommended for feasibility studies to enable estimates of recruitment/attrition, means/SD and changes in means to prepare for future clinical trials.35 To attain a sample of 50 participants at T3, it was estimated that 340 patients may need to be approached to allow for a 50% recruitment rate at T1, a 40% attrition rate between T1 and T2 and a 50% return rate at T3.

Existing rehabilitation programme

The existing rehabilitation programme comprised of six consecutive weekly sessions (each 3.5 hours) delivered by healthcare professionals (pain specialist physiotherapists and psychological well-being practitioners). The programme included understanding complex symptoms, sleep hygiene, graded exercise, goal setting, relaxation and mindfulness. Pacing was instructed in one session but was not informed or standardised by any particular guide or framework.

Activity pacing framework standardised programme

The existing 6-week programme was modified though restructuring and standardisation using the activity pacing framework. Activity pacing was formally instructed on two sessions (weeks 2–3). However, activity pacing was referenced throughout the programme in relation to other coping strategies, for example, how activity pacing can assist graded exercise (weeks 1–5) or set-back management (week 6). In comparison to the existing rehabilitation programme, the activity pacing framework standardised programme included more in-depth discussions of activity behaviours (avoidance, overactivity-underactivity cycling and excessive persistence) to assist patients to identify their current approach to activities. This aimed to facilitate patients’ recognition of which facets of activity pacing were most relevant to them. The two activity pacing sessions focused on the aims of activity pacing, barriers to activity pacing, facets of activity pacing (eg, breaking down tasks, switching between activities, having more consistent activity levels, allowing flexibility, gradually increasing the amount or variety of activities), and stages of activity pacing (introducing activity pacing, finding baselines, adjusting activities, planning, consistency, learning and progressing). Practical exercises included completing an activity diary to discuss patients’ activity patterns and setting goals in which activity pacing could be practised (see online supplemental figure 2. Content of the rehabilitation programme). Patients received a handout to summarise the key concepts of activity pacing. The healthcare professionals (as above) received training on the framework during a half-day session and could contact the lead researcher (DA) for any queries. All patients attended the standardised programme, but patients chose whether to participate in the study through their optional completion of the study questionnaires and consent form.

Data collection

Feasibility outcomes

Measures of feasibility included participant recruitment/attrition rates, adherence (number of sessions attended), acceptability (two satisfaction rating scales regarding the programme content and length where 0=dissatisfied and 10=fully satisfied), and missing data in the questionnaire. For every programme, healthcare professionals completed a 13-item fidelity checklist based on the conceptual model of the activity pacing framework to ensure their inclusion of key elements from the framework. Each clinician was observed once by the lead researcher.

Clinical measures

The self-reported paper questionnaire booklets (T1, T2 and T3) included standardised clinical measures. T1 could be completed during session one or at home, T2 could be completed during session 6, and T3 was sent in the post to be completed at home. Telephone reminders were made if the T3 questionnaires were not returned within 2 weeks. The T1 booklet contained demographic questions, in addition to following measures included in T2 and T3:

Activity pacing was measured using the APQ-28. The 26-item APQ was initially validated among patients with chronic pain/fatigue and contained five subthemes: Activity adjustment, Activity planning, Activity consistency, Activity acceptance and Activity progression (Cronbach’s alpha=0.72–0.92).36 (see online supplemental table 2, Five themes of the APQ-28 with examples.) Each item is scored between 0=‘never did this’ and 4=‘always did this’. Two items have been added that correspond to important aspects of activity pacing that emerged during the development of the activity pacing framework. The new items: APQ12: ‘I found a baseline amount of activities that I could do on ‘good’ and ‘bad’ days’ and APQ15: ‘I had a flexible approach with my activities’ were added to the subthemes of best conceptual fit (activity adjustment and activity acceptance, respectively). Each subtheme was calculated as a mean score. The APQ-28 subthemes, similarly to the following scales, permitted one missing item per subscale.

Current and usual pain were measured using two 11-point Numerical Rating Scales, where 0=‘no pain’ and 10=‘worst possible pain’.37

Physical fatigue (seven items) and mental fatigue (four items) were measured using the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire, where scores of 1=‘much worse than usual’ and 4=‘better than usual’.38 Two subscale scores were summated where higher scores indicated less fatigue.

Depression was measured using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the items of which are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition.39 Items were rated between 0=‘not at all’ and 3=‘nearly everyday’. Total scores of 1–4=minimal depression, 5–9=mild depression, 10–14=moderate depression and ≥15=severe depression.39 40

Anxiety was measured using the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment. Items were rated between 0=‘not at all’ and 3=‘nearly everyday’. Total scores of 5–9=mild anxiety, 10–14=moderate anxiety and ≥15=severe anxiety.41

Self-efficacy was measured using the 10-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) where items were rated between 0=‘not at all confident’ and 6=‘completely confident’. Total scores of PSEQ ≥40 indicate those patients who are more likely to continue implementing coping strategies/behavioural changes and PSEQ ≤16 are considered low.42

Avoidance was measured using the ‘Escape and Avoidance’ subscale of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-short version (PASS-20).43 The five items were rated between 0=‘never’ and 5=‘always’ where higher total scores indicated greater avoidance.

Physical and mental function were measured using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12). Two subscale scores (out of 100) were calculated using the SF-12 software (V.2; 1-week recall) where higher scores indicated better function.44

Health-related quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol five-dimensions, five-levels). The EQ-5D-5L was calculated as an index score.45 46

Data analysis

Feasibility outcomes and participants’ demographics were analysed using descriptive statistics. Clinical outcomes were estimated as changes in activity pacing and symptoms between T1-T2, T2-T3 and T1-T3 (mean change, 95% CIs). The validity of the modified APQ-28 was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha and item correlations; and sensitivity analyses explored the effects of including the two new APQ-28 items. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.26 statistical software (IBM).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) commenced during the initial planning stages of the mixed methods programme to develop and test the activity pacing framework. A meeting with five PPI representatives discussed the study purpose and practical issues around the proposed methods (online survey, nominal group technique and feasibility and acceptability studies). PPI guided on improving the accessibility of patients’ participation and reducing burden (eg, location and duration of meetings). A PPI representative has acted as an advisor on the study, involving commenting on study documents/questionnaire booklets and coding qualitative interviews. Acceptability interviews with patients explored practical issues surrounding the feasibility study,34 which will further assist the planning of a future randomised controlled trial (RCT) of activity pacing.

Results

Recruitment and T1 data collection commenced in May 2018 and T3 data collection ended in December 2019 due to attaining the target sample.

Demographics

Among the 107 participants who completed the baseline (T1) measures, participants were predominantly female (n=92, 86.0%) with a mean age of 55.25±12.83 years. Low back pain was most frequently reported (n=79, 73.8%) and CFS/ME least frequently reported (n=12, 11.2%). Sixty-five participants (61.3%) reported two or more conditions of chronic pain and/or fatigue. Of the 12 participants with CFS/ME, 10 participants reported CFS/ME as their main condition, and 11 reported at least one comorbidity of LBP (n=7), chronic widespread pain (n=6), fibromyalgia (n=7) or another condition (n=3). (see table 1 for participant demographics and table 2 for baseline scores for activity pacing and symptoms.)

Table 1.

Participant demographics at baseline (T1)

| Participants who completed T1 but not T2 | Participants who completed T1 and T2 | Total | |

| Gender | (n=42) | (n=65) | (n=107) |

| Male | 6 (14.3%) | 9 (13.8%) | 15 (14.0%) |

| Female | 36 (85.7%) | 56 (86.2%) | 92 (86.0%) |

| Age (years) | (n=41) Mean=56.07 (SD=13.85) |

(n=65) Mean=54.74 (SD=12.22) |

(n=106) Mean=55.25 (SD=12.83) |

| Ethnicity | (n=41) | (n=65) | (n=106) |

| White (British, Irish, other) | 39 (95.1%) | 60 (92.3%) | 99 (93.4%) |

| Black (Caribbean, African) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Mixed (white/black, white/Asian, other) | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (3.1%) | 3 (2.8%) |

| Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, other) | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (3.1%) | 3 (2.8%) |

| Asian Eastern (Chinese, other) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Living situation* | (n=42) | (n=65) | (n=107) |

| Lives alone | 7 (16.7%) | 10 (15.4%) | 17 (15.9%) |

| Lives with partner | 25 (59.5%) | 48 (73.8%) | 73 (68.2%) |

| Lives with children | 16 (38.1%) | 24 (36.9%) | 40 (37.4%) |

| Other | 2 (4.8%) | 1 (1.5%) | 3 (2.8%) |

| Employment | (n=42) | (n=65) | (n=107) |

| Working (full time, part time, in the house, student) | 13 (31.0%) | 31 (47.7%) | 44 (41.1%) |

| Not working (due to chronic pain/fatigue/other condition) | 15 (35.7%) | 19 (29.2%) | 34 (31.8%) |

| Retired/semiretired | 14 (33.3%) | 14 (21.5%) | 28 (26.2%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Conditions | (n=41) | (n=65) | (n=106) |

| Low back pain | 30 (73.2%) | 49 (75.4%) | 79 (74.5%) |

| Widespread pain | 19 (46.3%) | 33 (50.8%) | 52 (49.1%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 9 (22.0%) | 20 (30.8%) | 29 (27.4%) |

| CFS/ME | 6 (14.6%) | 6 (9.2%) | 12 (11.3%) |

| Other | 9 (22.0%) | 12 (18.5%) | 21 (19.8%) |

| No of the above conditions | (n=41) | (n=65) | (n=106) |

| 1 | 17 (41.5%) | 24 (36.9%) | 41 (38.7%) |

| 2 | 19 (46.3%) | 30 (46.2%) | 49 (46.2%) |

| 3 | 3 (7.3%) | 9 (13.8%) | 12 (11.3%) |

| 4 | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| 5 | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Duration of participants’ main condition (years) | (n=35) Mean=10.23 (SD=9.49) |

(n=61) Mean=12.94 (SD=11.36) |

(n=96) Mean=11.95 (SD=10.74) |

*Patients could select more than one answer.

CFS/ME, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Table 2.

Baseline scores for activity pacing and symptoms for all patients completing the baseline questionnaires (T1)

| Measures (range of scores) | Baseline scores for those completed T1 but not T2: mean (SD) |

Baseline scores for those completed T1 and T2: mean (SD) |

Total scores |

| APQ-28 activity adjustment (0–4) | (n=42) 1.96 (0.87) | (n=64) 1.74 (0.76) | (n=106) 1.83 (0.81) |

| APQ-28 activity planning (0–4) | (n=42) 1.57 (1.03) | (n=65) 1.44 (0.95) | (n=107) 1.49 (0.98) |

| APQ-28 activity consistency (0–4) | (n=42) 1.91 (0.91) | (n=65) 1.82 (0.96) | (n=107) 1.85 (0.94) |

| APQ-28 activity acceptance (0–4) | (n=42) 1.97 (1.02) | (n=65) 1.87 (0.84) | (n=107) 1.91 (0.92) |

| APQ-28 activity progression (0–4) | (n=42) 1.59 (1.05) | (n=65) 1.45 (0.88) | (n=107) 1.51 (0.95) |

| Current pain (0–10) | (n=41) 6.83 (1.96) | (n=65) 6.63 (1.97) | (n=106) 6.71 (1.96) |

| Usual pain (0–10) | (n=40) 7.72 (1.43) | (n=63) 7.30 (1.82) | (n=103) 7.47 (1.69) |

| Physical fatigue (7-28) | (n=41) 14.18 (5.12) | (n=62) 15.22 (4.10) | (n=103) 14.81 (4.54) |

| Mental fatigue (4-16) | (n=42) 8.79 (3.22) | (n=64) 8.86 (2.77) | (n=106) 8.83 (2.94) |

| Depression (0–27) | (n=40) 12.63 (7.61) | (n=64) 13.66 (6.38) | (n=104) 13.26 (6.86) |

| Anxiety (0–21) | (n=41) 9.86 (6.64) | (n=65) 9.91 (5.47) | (n=106) 9.89 (5.92) |

| Self-efficacy (0–60) | (n=42) 26.26 (13.85) | (n=65) 25.29 (10.60) | (n=107) 25.67 (11.93) |

| Avoidance (0–25) | (n=42) 12.95 (6.74) | (n=64) 13.27 (5.49) | (n=106) 13.14 (5.98) |

| Physical function (0–100) | (n=42) 33.67 (9.75) | (n=63) 34.15 (8.23) | (n=105) 33.96 (8.82) |

| Mental function (0–100) | (n=42) 42.22 (11.51) | (n=63) 38.52 (11.10) | (n=105) 40.00 (11.36) |

| Quality of life (0–1) | (n=40) 0.41 (0.26) | (n=60) 0.43 (0.25) | (n=100) 0.42 (0.25) |

Activity pacing (APQ-28), Pain (Numerical Rating Scale 0–10), Physical/mental fatigue (Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire), Depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), Anxiety (Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7), Self-efficacy (Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire), Avoidance (Escape and avoidance subscale of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20), Physical/mental function (Short-Form 12), Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L EuroQol five-dimensions, five-levels index score).

APQ-28, 28-item Activity Pacing Questionnaire.

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment and attrition (objective 1)

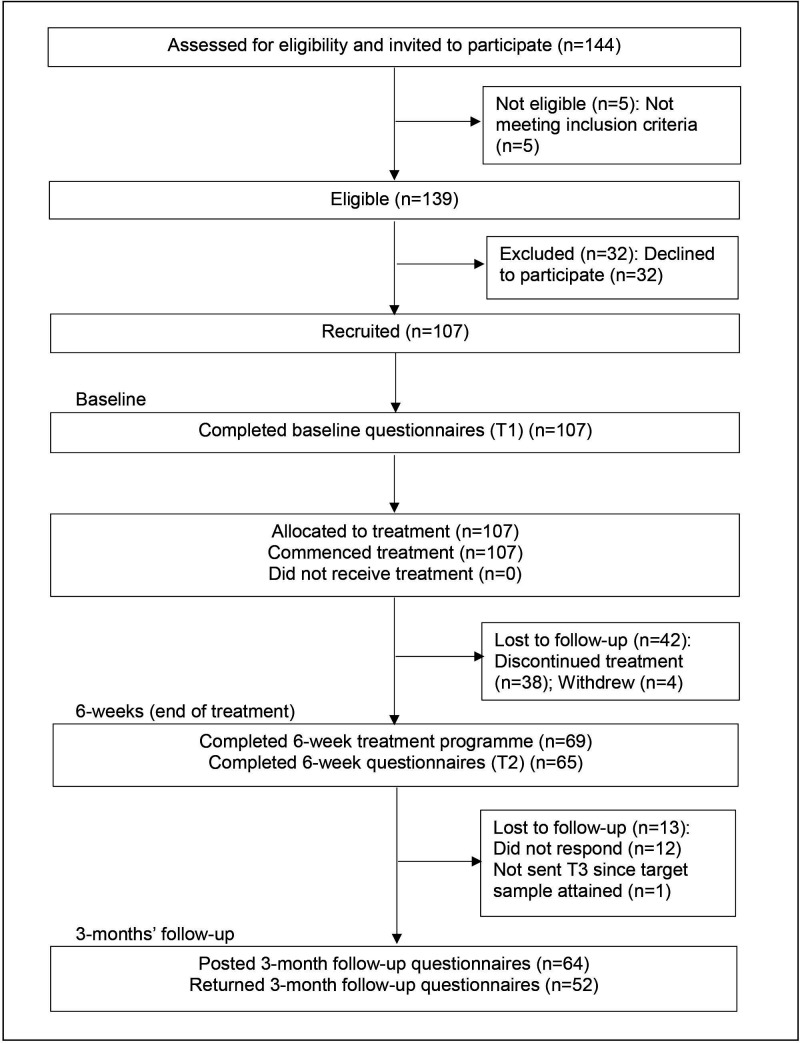

Of the 144 patients invited to participate, 139 were eligible (96.5%). The reasons for ineligibility included: three patients reported only neck pain, one patient reported neck/knee pain and one patient reported thoracic pain. Of the 139 eligible patients, 107 (77.0%) were recruited at T1, 69 (64.5%) completed the 6-week programme and 65 (60.7%) completed the T2 measures (attrition rate=39.3%). Fifty-two participants completed T3 (80.0% of T2; attrition rate from T1=51.4%). There were no serious adverse events (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through the study. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Of the 107 participants, the median number of rehabilitation programme sessions attended was five (58.9% participants attended ≥5 sessions); 83.2% participants attended at least one activity pacing session and 56.1% attended both activity pacing sessions. Of the 65 participants who completed T2, the median number of sessions attended was six (89.2% participants attended ≥5 sessions); 100% of participants attended at least one activity pacing specific session and 54 (83.1%) participants attended both activity pacing sessions. There were no statistically significant differences between participants who completed T2 or dropped out in terms of demographics or baseline symptoms. Of the 12 participants with CFS/ME, six completed T2 (50%) and six completed T3 (100% of T2, 50% of T1); whereas 59 of the 95 participants without CFS/ME completed T2 (62%) and 46 completed T3 (78% of T2 and 48% of T1).

Acceptability of the rehabilitation programme/questionnaires (objective 1)

On T2, participants rated their satisfaction of the length and content of the rehabilitation programme as mean=8.8 (SD=1.7) and 9.1 (SD=1.5), respectively. The satisfaction of only those participants with CFS/ME was mean=9.0 (SD=0.9) and 9.2 (SD=1.0).

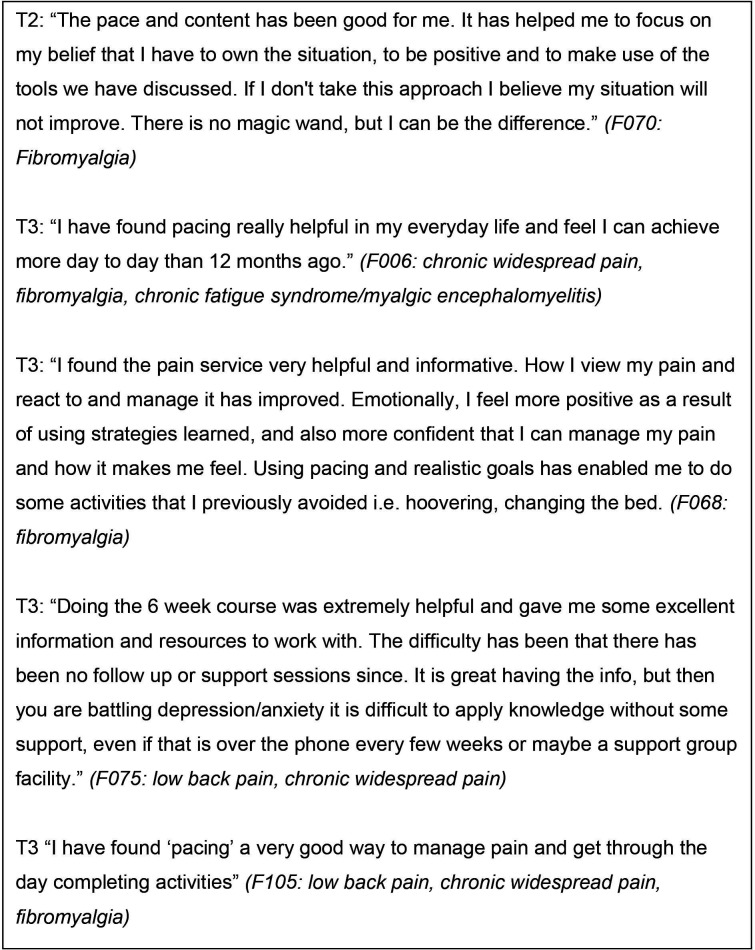

There were minimal missing data in the questionnaire booklets (approximately 1%). Some participants wrote comments regarding their perceived benefits of implementing activity pacing and other coping strategies. Two participants wished for a longer programme or a follow-up session (see figure 3 for examples of participants’ comments).

Figure 3.

Participants’ written comments following attending the rehabilitation programme.

Fidelity to the activity pacing framework (objective 2)

Each healthcare professional observation demonstrated good adherence to the framework against a number of key points. Healthcare professionals reported 100% adherence in their fidelity checklists for each rehabilitation programme. Healthcare professionals reported that some participants spent over 20 min completing the questionnaire booklet, and that not all patients completed the activity diaries.

Interventions between T2 and T3

Of the 52 respondents at T3, two patients received lumbar epidural steroid injections, one patient had acupuncture, one attended a chiropractor and one patient had knee surgery.

Clinical outcomes

Validity of the APQ-28 (objective 3)

At T1, the two new APQ-28 items showed ease of completion through minimal missing answers (Item APQ12=0 missing answers, Item APQ15=1 missing answer). The scores of the new items utilised the full range, and the mean scores (Items APQ12=1.67 and APQ15=1.91) sat within the range of the other APQ-28 items (mean=1.17–2.78). The new items demonstrated optimal fit with their allocated subthemes via highest interitem correlations and item-total correlations (item total correlations: APQ12 and Activity adjustment, rs(106)=0.76, p<0.001; Item APQ15 and Activity acceptance, r(106)=0.68, p<0.001). The internal consistency for Activity adjustment increased with the addition of Item APQ12 (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86 to 0.88), and for activity acceptance with the addition of item APQ15 (Cronbach’s alpha=0.68 to 0.72). The internal consistency of the other APQ-28 subthemes were: activity planning=0.86, activity consistency=0.80 and activity progression=0.69.

Mean changes in activity pacing and symptoms (objective 3)

Between T1 and T2, all five APQ-28 subtheme mean scores increased, indicating improved activity pacing. There were small reductions in APQ-28 scores between T2 and T3. However, all five subthemes showed overall improvements between T1-T3, with Activity planning showing the greatest increases (see table 3). Sensitivity analyses showed marginal increases in mean changes following the addition of the two new APQ-28 items.

Table 3.

Mean changes in the five subthemes of activity pacing (APQ-28) between T1 (baseline), T2 (end of 6 weeks’ treatment) and T3 (3 months’ follow-up)

| Measures | T1 mean (SD) T2 mean (SD) |

T2-T1 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) | T2 mean (SD) T3 mean (SD) |

T3-T2 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) | T3 mean T1 mean |

T3-T1 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) |

| APQ-28 activity adjustment | (n=63) T1 mean=1.73 (0.77) T2 mean=2.43 (0.73) |

0.70 (95% CI=0.48 to 0.91); d=0.91 | (n=51) T2 mean=2.44 (0.72) T3 mean=2.32 (0.90) |

−0.12 (95% CI= −0.36 to 0.11); d=−0.17 | (n=50) T1 mean=1.75 (0.78) T3 mean=2.33 (0.90) |

0.58 (95% CI=0.33 to 0.83); d=0.74 |

| APQ-28 activity planning | (n=65) T1 mean=1.44 (0.95) T2 mean=2.42 (0.87) |

0.99 (95% CI=0.72 to 1.26); d=1.03 | (n=52) T2 mean=2.45 (0.87) T3 mean=2.06 (1.02) |

−0.39 (95% CI= −0.70 to −0.07); d=−0.45 | (n=52) T1 mean=1.42 (0.96) T3 mean=2.06 (1.02) |

0.64 (95% CI=0.36 to 0.92); d=0.67 |

| APQ-28 activity consistency | (n=65) T1 mean=1.82 (0.96) T2 mean=2.65 (0.74) |

0.84 (95% CI=0.60 to 1.07); d=0.86 | (n=52) T2 mean=2.66 (0.71) T3 mean=2.37 (0.72) |

−0.29 (95% CI= −0.54 to −0.04); d=−0.41 | (n=52) T1 mean=1.86 (1.00) T3 mean=2.37 (0.72) |

0.51 (95% CI=0.24 to 0.78); d=0.51 |

| APQ-28 activity acceptance | (n=65) T1 mean=1.87 (0.84) T2 mean=2.55 (0.72) |

0.67 (95% CI=0.46 to 0.89); d=0.81 | (n=52) T2 mean=2.57 (0.73) T3 mean=2.42 (0.95) |

−0.15 (95% CI= −0.38 to 0.08); d=−0.21 | (n=52) T1 mean=1.84 (0.91) T3 mean=2.42 (0.95) |

0.58 (95% CI=0.33 to 0.84); d=0.64 |

| APQ-28 activity progression | (n=65) T1 mean=1.45 (0.88) T2 mean=2.39 (0.89) |

0.94 (95% CI=0.65 to 1.22); d=1.07 | (n=52) T2 mean=2.40 (0.91) T3 mean=2.00 (0.91) |

−0.40 (95% CI= −0.75 to −0.05); d=−0.44 | (n=52) T1 mean=1.45 (0.85) T3 mean=2.00 (0.91) |

0.56 (95% CI=0.24 to 0.87); d=0.65 |

APQ-28, 28-item Activity Pacing Questionnaire.

Between T1 and T2, the mean scores of all symptoms improved. Current pain reduced more than usual pain. Physical and mental fatigue both improved, as did self-efficacy and quality of life. Mental function improved more than physical function. Depression, anxiety and avoidance all reduced. There was some deterioration in symptoms between T2-T3, but between T1 and T3 all symptoms demonstrated clear improvements except avoidance (−1.46, 95% CI −3.02 to 0.10) and physical function (1.62, 95% CI −0.81 to 4.06) (see table 4). Observing only the subgroup of participants with CFS/ME, improvements were seen between T1-T2 and T1-T3 across all APQ-28 subthemes and symptoms.

Table 4.

Mean changes in measures of symptoms between T1 (baseline), T2 (end of 6 weeks’ treatment) and T3 (3 months’ follow-up)

| Measures | T1 mean (SD) T2 mean (SD) |

T2-T1 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) | T2 mean (SD) T3 mean (SD) |

T3-T2 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) | T3 mean T1 mean |

T3-T1 mean change (95% CI); effect size(d) |

| Current pain | (n=65) T1 mean=6.63 (1.97) T2 mean=5.31 (2.38) |

−1.32 (95% CI= −1.91 to −0.74); d=−0.67 | (n=52) T2 mean=5.04 (2.36) T3 mean=5.65 (2.31) |

0.62 (95% CI=−0.08 to 1.31); d=0.26 | (n=52) T1 mean=6.58 (1.99) T3 mean=5.65 (2.31) |

−0.92 (95% CI= −1.58 to −0.27); d=−0.47 |

| Usual pain | (n=65) T1 mean=7.30 (1.82) T2 mean=6.62 (2.08) |

−0.68 (95% CI= −1.19 to −0.18); d=−0.37 | (n=51) T2 mean=6.53 (2.10) T3 mean=6.55 (1.91) |

0.02 (95% CI=−0.48 to 0.52); d=0.01 | (n=50) T1 mean=7.30 (1.62) T3 mean=6.54 (1.93) |

−0.76 (95% CI= −1.27 to −0.25); d=−0.47 |

| Physical fatigue | (n=62) T1 mean=15.22 (4.10) T2 mean=20.31 (3.92) |

5.08 (95% CI=3.95 to 6.21); d=1.24 | (n=51) T2 mean=20.47 (4.13) T3 mean=18.12 (4.18) |

−2.35 (95% CI= −3.44 to −1.26); d=−0.57 | (n=49) T1 mean=15.35 (3.90) T3 mean=18.18 (4.16) |

2.84 (95% CI=1.34 to 4.33); d=0.73 |

| Mental fatigue | (n=64) T1 mean=8.86 (2.77) T2 mean=11.28 (2.43) |

2.42 (95% CI=1.75 to 3.10); d=0.87 | (n=51) T2 mean=11.45 (2.20) T3 mean=10.92 (2.34) |

−0.53 (95% CI= −1.17 to 0.11); d=−0.24 | (n=51) T1 mean=8.94 (2.51) T3 mean=10.92 (2.34) |

1.98 (95% CI=1.33 to 2.64); d=0.79 |

| Depression | (n=63) T1 mean=13.65 (6.44) T2 mean=7.14 (6.09) |

−6.51 (95% CI= −7.72 to −5.31); d=−1.01 | (n=51) T2 mean=6.27 (5.49) T3 mean=9.23 (5.75) |

2.96 (95% CI=1.64 to 4.29); d=0.54 | (n=51) T1 mean=13.18 (6.35) T3 mean=9.09 (5.76) |

−4.09 (95% CI= −5.61 to −2.57); d=−0.64 |

| Anxiety | (n=65) T1 mean=9.91 (5.47) T2 mean=5.40 (5.13) |

−4.51 (95% CI= −5.60 to −3.42); d=−0.82 | (n=52) T2 mean=4.65 (4.47) T3 mean=6.10 (5.23) |

1.44 (95% CI=0.55 to 2.33); d=0.32 | (n=52) T1 mean=9.47 (5.06) T3 mean=6.10 (5.23) |

−3.37 (95% CI= −4.63 to −2.12); d=−0.67 |

| Self-efficacy | (n=65) T1 mean=25.29 (10.60) T2 mean=36.29 (14.12) |

11.00 (95% CI=8.44 to 13.56); d=1.04 | (n=52) T2 mean=37.96 (14.12) T3 mean=34.68 (14.26) |

−3.28 (95% CI= −7.17 to 0.60); d=−0.23 | (n=52) T1 mean=25.85 (10.74) T3 mean=34.68 (14.26) |

8.83 (95% CI=5.86 to 11.81); d=0.82 |

| Avoidance | (n=64) T1 mean=13.27 (5.49) T2 mean=10.28 (5.89) |

−2.98 (95% CI= −4.43 to −1.54); d=−0.54 | (n=52) T2 mean=10.85 (5.93) T3 mean=12.12 (5.79) |

1.27 (95% CI=−0.27 to 2.81); d=0.21 | (n=52) T1 mean=13.58 (5.66) T3 mean=12.12 (5.79) |

−1.46 (95% CI= −3.02 to 0.10); d=−0.26 |

| Physical function | (n=63) T1 mean=34.15 (8.23) T2 mean=38.82 (9.06) |

4.67 (95% CI=2.69 to 6.65); d=0.57 | (n=49) T2 mean=39.45 (8.72) T3 mean=36.63 (9.69) |

−2.82 (95% CI= −5.29 to −0.35); d=−0.32 | (n=47) T1 mean=34.92 (7.98) T3 mean=36.55 (9.81) |

1.62 (95% CI=−0.81 to 4.06); d=0.20 |

| Mental function | (n=63) T1 mean=38.52 (11.10) T2 mean=45.83 (11.48) |

7.30 (95% CI=4.49 to 10.12); d=0.66 | (n=49) T2 mean=46.75 (10.82) T3 mean=44.78 (10.44) |

−1.97 (95% CI= −5.22 to 1.29); d=−0.18 | (n=47) T1 mean=38.61 (10.65) T3 mean=44.56 (10.60) |

5.95 (95% CI=2.83 to 9.08); d=0.56 |

| Quality of life | (n=59) T1 mean=0.43 (0.25) T2 mean=0.56 (0.28) |

0.13 (95% CI=0.07 to 0.18); d=0.52 | (n=48) T2 mean=0.60 (0.25) T3 mean=0.51 (0.28) |

−0.09 (95% CI= −0.14 to −0.03); d=−0.36 | (n=45) T1 mean=0.45 (0.24) T3 mean=0.52 (0.29) |

0.07 (95% CI=0.001 to 0.14); d=0.29 |

Pain (Numerical Rating Scale 0–10), Physical/mental fatigue (Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire), Depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), Anxiety (Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7), Self-efficacy (Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire), Avoidance (Escape and avoidance subscale of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20), Physical/mental function (Short-Form 12), Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L EuroQol five-dimensions, five levels index score).

Discussion

This study fulfilled the original aims of testing the feasibility and acceptability of using a new activity pacing framework to standardise instructions of activity pacing to assist planning a future effectiveness RCT. The study recruited to target and patients with chronic pain and chronic fatigue demonstrated both improvements in activity pacing strategies and reductions in symptoms.

Feasibility

The activity pacing framework demonstrated feasibility through excellent fidelity to the framework by healthcare professionals via self-reported checklists and observations. Acceptability was demonstrated through patients’ high satisfaction scores. Not all patients completed the activity diaries, however, this was optional for patients to facilitate their own self-reflection.

The recruitment rate (77%) was higher than estimated in the study protocol (50%). This was similar to a study exploring a 5-week exercise programme for chronic hip pain (recruitment rate=76%),47; and this rate is considered ‘Good’ using cut-off levels of 80%=excellent and 70%=good from a feasibility study exploring a mind-body physical activity programme for chronic pain.48 The attrition rate between T1 and T2 (39.3%) was as predicted in the protocol (40%), and lower than the 60% attrition rates reported across other studies investigating programmes for chronic pain.20 The attrition rate between T2 and T3 (20.0%) was lower than predicted in the protocol (50%), and the target sample size proved feasible to attain. These recruitment/attrition rates will help to plan the progression criteria used in a future pilot RCT of activity pacing.

Regarding treatment adherence, only 56.1% of participants recruited at T1 attended both activity pacing sessions. Many participants (n=18, 16.8%) dropped out after the first session and therefore did not attend any activity pacing sessions. Reasons for early drop-out often include unrealistic expectations of symptom improvement, low motivation, or confidence to commit to programmes or behavioural changes.20 In comparison, attendance rates of both activity pacing sessions among those who completed T2 were 83.1%, and 89.2% of participants attended five or more sessions. This is comparable to adherence rates of 81% seen elsewhere,47; and adherence rates have been considered as ‘Excellent’ when 70% or more participants complete 75% of sessions.48 However, within this study, the interpretation of high attendance rates from those who completed T2 are considered more modestly following the drop outs after week 1.

Participants reported the condition of low back pain most frequently and CFS/ME the least frequently, as per current prevalence rates.49 50 Our findings reiterate the high occurrence of comorbidities, and frequent coexistence of chronic pain among patients with CFS/ME.9 Participants with CFS/ME demonstrated improvements in symptoms following treatment, in comparison to other studies in which pacing has been ineffective.31 Disparate to the study by White et al31 the activity pacing framework encourages a rehabilitative approach that facilitates increased function rather than aiming to reduce symptoms. The effects of rehabilitative approaches to activity pacing for patients with both chronic pain and fatigue requires further investigation using effectiveness trials.

Clinical outcomes

Activity pacing improved across all APQ-28 subthemes, the largest improvement being for Activity planning. This theme refers to planning activities, setting time targets and assessing activity levels36; practical facets of activity pacing which may be more accessible to change. Comparably, participants showed smaller improvements in Activity acceptance. This subtheme includes setting realistic goals and allowing flexibility; facets that involve changing previous behaviours or self-enforced rules. The APQ-28 detected multidimensional changes in activity pacing, and the two new items appeared to complement the scale. Further study will fully validate the APQ-28 in a larger sample and estimate minimally important changes.

The aims of the activity pacing framework are to improve patients’ function and quality of life. Improvements in physical function were seen between T1 and T2 (mean change=4.67) that were greater than the minimally clinically important change (3.29).51 There were also reductions in avoidance between T1 and T2. It is intended that the quota-contingent, operant approach of the activity pacing framework encourages a reduction in avoidance through setting meaningful and realistic goals towards activity, rather than stopping activities with the aim of reducing/avoiding symptoms as per energy conservation approaches. Similarly, in an RCT comparing an operant approach with energy conservation, Racine et al30 found the operant approach, but not energy conservation was associated with reduced avoidance among patients with fibromyalgia. This, together with greater improvements in depressive symptoms following the operant approach over energy conservation, led to recommendations towards the operant approach for patients with fibromyalgia.30 The current study found that pre–post treatment (T1-T2) improvements in both avoidance and physical function showed some decline at 3 months’ follow-up. The authors suggest that physical function may be a component of rehabilitation in which patients feel least confident, especially those with avoidant behaviours.20 This may have implications for future programmes to integrate follow-up sessions to encourage longer-term maintenance of physical activity. In comparison, Racine et al30 found improvements in physical activity following both operant pacing and energy conservation approaches. Similarly to this study, Racine et al30 implemented handouts, homework and goal setting to encourage patients’ uptake of activity pacing. However, both of the interventions explored by Racine et al30 were of greater duration than the current study, comprising of 10 2 hour stand-alone pacing sessions with a 3-month booster session. Within the current study, improvements in mental function between T1 and T2 (mean change=7.3) were better maintained between T1 and T3 (mean change=5.95); and both higher than the minimally clinically important change (3.77).51 Quality of life also improved between T1 and T2 (mean change=0.13) and much of this improvement was maintained between T1 and T3 (mean change=0.07); both changes exceeded the minimally important difference (0.037±0.008).52

The activity pacing framework additionally aims to increase patients’ self-efficacy. Improvements in self-efficacy were found between T1 (mean=25.29) and T2 (mean=36.29), which were well maintained at T3 (mean=34.68). Scores were lower than the ≥40 cut-off. However, an improvement of >5.5 was attained which is considered a minimally important change.53 Both physical and mental fatigue improved, and improvements in mental fatigue appeared to be better maintained at T3. Comparisons to minimally important changes are unavailable.

Psychological health improved following the rehabilitation programme, including reduced depression scores from moderate to mild (T1=13.7, T2=7.1, T3=9.1); with a clinically significant reduction (≥5) between T1 and T2.40 Mean anxiety scores reduced (T1=9.9, T2=5.4 and T3=6.10), and remained within the classification of mild anxiety.41 Although reductions in pain were not a direct aim of the current treatment, lower pain severity was reported. Despite the increased intensity of pacing sessions contained within the RCT comparing the operant approach to energy conservation, Racine et al30 found that neither pacing approach effectively reduced symptoms of pain or fatigue.

Strengths and limitations

This study was an early feasibility study that primarily aimed to explore whether a new activity pacing framework could be implemented in the clinical setting. While this study fulfilled its original aims, it is limited by the absence of a priori progression criteria. However, the findings from this study will help to inform the progression criteria that are used to determine whether to progress to a full clinical trial from a future pilot RCT. Despite recruiting to target, this sample was not powered with a control arm to determine treatment effectiveness. As per other studies exploring activity pacing, activity pacing was instructed as one component of the rehabilitation programme.5 Therefore, improvements in symptoms may have resulted from any combination of coping strategies. A future RCT will implement a suitable control to explore the effects of activity pacing, while implementing the activity pacing framework in a clinically relevant setting, including alongside other coping strategies.

The generalisability of this study is limited to a sample of predominantly females and white ethnic origin. Recruitment occurred only at one Pain Service and this service had an existing rehabilitation programme for both chronic pain and fatigue. Bias may have arisen through the lead researcher delivering the healthcare professionals’ training and undertaking the observations. Further work will test the activity pacing framework and study protocol across other healthcare services and explore feasibility and fidelity over wider geographical locations.

It is unknown what potential bias was caused by the attrition rate. However, there were no differences at baseline between those who completed the programme and those who dropped out. It is possible that patients who completed T2 and T3 possibly felt greater benefits from the treatment and were more motivated to respond to the follow-up questionnaires. The attrition rate may be reflective of some of the clinical challenges and missed appointments surrounding the complexity of chronic pain/fatigue. Further research could explore whether providing a follow-up treatment session improves commitment to activity pacing.

Modifications for future study

Since more patients completed the T1 questionnaires during the rehabilitation sessions than at home, this may be the preferable mode of distribution of paper questionnaires. To lessen the time taken to complete the questionnaires, the PASS-20 may be considered for exclusion in future study. The whole 20-item PASS scale was included for reliability and validity, but data specifically from the Escape and Avoidance subscale was explored. Modifications to the inclusion criteria may include patients with any chronic spinal pain, including cervical/thoracic pain due to the frequent and similar presentation at rehabilitation services.

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to explore the clinical utility of a comprehensive activity pacing framework developed for both chronic pain and chronic fatigue. The newly developed activity pacing framework proved feasible to use clinically by healthcare professionals. Patients with both chronic pain and fatigue implemented greater activity pacing strategies following treatment, alongside reporting improvements in quality of life, psychological well-being, self-efficacy, pain and fatigue. Physical function and avoidance improved to a lesser extent and for the shorter-term. Future study will use the activity pacing framework in an effectiveness RCT to explore the effects of activity pacing on symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all of the patients and healthcare professionals who were involved in this study. We would also like to acknowledge our statistical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: DA, AMK, PK, SW and LM all contributed to the conception and design of the study. DA undertook the acquisition of the data. DA, AMK, PK, SW and LM all contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. DA, AMK, PK, SW and LM contributed to drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content and have approved the final version for publication. DA, AMK, PK, SW and LM are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. DA is the guarantor for this work.

Funding: This work was supported by a Health Education England/National Institute for Health Research (HEE/NIHR) Clinical Lectureship (grant number: ICA-CL-2015-01-019).

Disclaimer: This paper presents independent research funded by Health Education England/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Clinical Lectureship (ICA-CL-2015-01-019)). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Comprehensive data are presented in the manuscript tables, including participant demographics, baseline measures and post-treatment measures. Deidentified participant data may be available from the corresponding author, (Deborah.Antcliff@nca.nhs.uk) on reasonable request. Reuse is permitted for health and care research as long as the original authors are acknowledged. The protocol can also be requested from the author or accessed at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03497585).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the London-Surrey Research Ethics Committee (18/LO/0655).

References

- 1.Torrance N, Smith BH, Elliott AM, et al. Potential pain management programmes in primary care. A UK-wide questionnaire and Delphi survey of experts. Fam Pract 2011;28:41–8. 10.1093/fampra/cmq081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijs J, Meeus M, De Meirleir K. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in chronic fatigue syndrome: recent developments and therapeutic implications. Man Ther 2006;11:187–91. 10.1016/j.math.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielson WR, Jensen MP, Karsdorp PA, et al. Activity pacing in chronic pain: concepts, evidence, and future directions. Clin J Pain 2013;29:461–8. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182608561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antcliff D, Keenan A-M, Keeley P, et al. Survey of activity pacing across healthcare professionals informs a new activity pacing framework for chronic pain/fatigue. Musculoskeletal Care 2019;17:335–45. 10.1002/msc.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abonie US, Sandercock GRH, Heesterbeek M, et al. Effects of activity pacing in patients with chronic conditions associated with fatigue complaints: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2020;42:613–22. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1504994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, et al. The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:468–76. 10.1093/ije/dyi265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeus M, Nijs J. Central sensitization: a biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:465–73. 10.1007/s10067-006-0433-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis LL, Kroenke K, Monahan P, et al. The SPADE symptom cluster in primary care patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2016;32:388–93. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeus M, Nijs J, Meirleir KD. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2007;11:377–86. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavel ME. Somatic symptom disorders without known physical causes: one disease with many names? Am J Med 2015;128:1054–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yunus MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007;36:339–56. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nijs J, Meeus M, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. In the mind or in the brain? Scientific evidence for central sensitisation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest 2012;42:203–12. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arendt-Nielsen L, Morlion B, Perrot S, et al. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur J Pain 2018;22:216–41. 10.1002/ejp.1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000;85:317–32. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Man Ther 2003;8:130–40. 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00051-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ericsson A, Mannerkorpi K. How to manage fatigue in fibromyalgia: nonpharmacological options. Pain Manag 2016;6:331–8. 10.2217/pmt-2016-0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Pain Society . Guidelines for pain management programmes for adults. London: British Pain Society, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beissner K, Henderson CR, Papaleontiou M, et al. Physical therapists' use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults with chronic pain: a nationwide survey. Phys Ther 2009;89:456–69. 10.2522/ptj.20080163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Booth J, Moseley GL, Schiltenwolf M, et al. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskeletal Care 2017;15:413–21. 10.1002/msc.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RJ, Hurley RW, Staud R, et al. Cognitive-motivational influences on health behavior change in adults with chronic pain. Pain Med 2016;17:1079–93. 10.1111/pme.12929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkholtz M, Aylwin L, Harman RM. Activity pacing in chronic pain management: One aim, but which method? Part one: introduction and literature review. Br J Occupat Therapy 2004;67:447–52. 10.1177/030802260406701005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abonie US, Edwards AM, Hettinga FJ. Optimising activity pacing to promote a physically active lifestyle in medical settings: a narrative review informed by clinical and sports pacing research. J Sports Sci 2020;38:590–6. 10.1080/02640414.2020.1721254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamieson-Lega K, Berry R, Brown CA. Pacing: a concept analysis of the chronic pain intervention. Pain Res Manag 2013;18:207–13. 10.1155/2013/686179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrews N, Deen M. Defining activity pacing: is it time to jump off the merry-go-round? J Pain 2016;17:1359–62. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews NE, Strong J, Meredith PJ. Activity pacing, avoidance, endurance, and associations with patient functioning in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:2109–21. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy SL, Clauw DJ. Activity pacing: what are we measuring and how does that relate to intervention? Pain 2010;149:582–3. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell JW, Piano-Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. California, USA: Sage Publications Ltd, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antcliff D, Keenan A-M, Keeley P, et al. Engaging stakeholders to refine an activity pacing framework for chronic pain/fatigue: a nominal group technique. Musculoskeletal Care 2019;17:354–62. 10.1002/msc.1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racine M, Jensen MP, Harth M, et al. Operant learning versus energy conservation activity pacing treatments in a sample of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Pain 2019;20:420–39. 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011;377:823–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60096-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lancaster GA, Thabane L. Guidelines for reporting non-randomised pilot and feasibility studies. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019;5:114. 10.1186/s40814-019-0499-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. 10.1136/bmj.i5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antcliff D, Keenan A-M, Keeley P, et al. "Pacing does help you get your life back": the acceptability of a newly developed activity pacing framework for chronic pain/fatigue. Musculoskeletal Care 2021 10.1002/msc.1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:301–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antcliff D, Campbell M, Woby S, et al. Assessing the psychometric properties of an activity pacing questionnaire for chronic pain and fatigue. Phys Ther 2015;95:1274–86. 10.2522/ptj.20140405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. What is the maximum number of levels needed in pain intensity measurement? Pain 1994;58:387–92. 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90133-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:147–53. 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:345–59. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;11:153–63. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCracken LM, Dhingra L. A short version of the pain anxiety symptoms scale (PASS-20): preliminary development and validity. Pain Res Manag 2002;7:45–50. 10.1155/2002/517163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng Y-S, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health 2012;15:708–15. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bearne LM, Walsh NE, Jessep S, et al. Feasibility of an exercise-based rehabilitation programme for chronic hip pain. Musculoskeletal Care 2011;9:160–8. 10.1002/msc.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenberg J, Lin A, Zale EL, et al. Development and early feasibility testing of a Mind-body physical activity program for patients with heterogeneous chronic pain; the GetActive study. J Pain Res 2019;12:3279–97. 10.2147/JPR.S222448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018;391:2356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.NICE . Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomylitis (or encephalopathy). NICE clinical guideline 53 London 2007.

- 51.Díaz-Arribas MJ, Fernández-Serrano M, Royuela A, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in quality of life for patients with low back pain. Spine 2017;42:1908–16. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McClure NS, Sayah FA, Xie F, et al. Instrument-Defined estimates of the minimally important difference for EQ-5D-5L index scores. Value Health 2017;20:644–50. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiarotto A, Vanti C, Cedraschi C, et al. Responsiveness and minimal important change of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire and short forms in patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain 2016;17:707–18. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045398supp001.pdf (196KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Comprehensive data are presented in the manuscript tables, including participant demographics, baseline measures and post-treatment measures. Deidentified participant data may be available from the corresponding author, (Deborah.Antcliff@nca.nhs.uk) on reasonable request. Reuse is permitted for health and care research as long as the original authors are acknowledged. The protocol can also be requested from the author or accessed at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03497585).