Abstract

Introduction

More research and policy action are needed to improve migrant health in areas such as sexual health and blood-borne viruses (SHBBV). While Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice Surveys (KAPS) can inform planning, there are no SHBBV KAPS suitable for use across culturally and linguistically diverse contexts. This study pretests one instrument among people born in Sub-Saharan Africa, South-East and North-East Asia living in Australia.

Methods

Employees of multicultural organisations were trained to collect data over three rounds using a hybrid qualitative pretesting method. Two researchers independently coded data. Researchers made revisions to survey items after each round. Responses to feedback questions in the final survey were analysed.

Results

Sixty-two participants pretested the survey. Issues were identified in all three rounds of pretesting. Of the 77 final survey respondents who responded to a survey experience question, 21% agreed and 3% strongly agreed with the statement ‘I found it hard to understand some questions/words’.

Conclusion

It is essential to pretest SHBBV surveys in migrant contexts. We offer the following pretesting guidance: (1) large samples are needed in heterogeneous populations; (2) intersectionality must be considered; (3) it may be necessary to pretest English language surveys in the participants’ first language; (4) bilingual/bicultural workers must be adequately trained to collect data; (5) results need to be interpreted in the context of other factors, including ethics and research aims; and (6) pretesting should occur over multiple rounds.

Keywords: public health, HIV & AIDS, public health, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An iterative ‘test-revise-repeat’ approach to pretesting was adopted, in line with the best practice.

While the pretesting sample was culturally diverse, limited attempts were made to purposively recruit people representing a range of gender expressions and sexualities.

The use of bicultural/bilingual workers to lead recruitment and data collection was a strength but training materials and processes need refinement for lay researchers.

Pretesting groups comprised people from different language backgrounds with differing levels of English proficiency which may have impacted on the amount and quality of the data obtained.

The amount of pretesting able to be conducted was limited by resource constraints but results were triangulated by analysing feedback on the final English survey.

Introduction

More research and policy action are needed to advance the migrant health agenda.1 The University College London (UCL) and Lancet Commission on Migration and Health noted that areas such as sexual health can be particularly challenging to address due to personal and cultural sensitivities. It is known that migrant populations have higher burdens of sexually transmissible infections and blood-borne viruses compared with general populations. For instance, 42% and 38% of HIV diagnoses in Western Europe and Australia respectively were among migrant populations.2 3

Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) surveys can assist policy-makers and service providers to understand population health disparities and inform service planning. However, there is currently no ‘standard, globally-recognized instrument to measure sexual practices, behaviours and sexual health related outcomes’.4 While a variety of validated sexual health and blood-borne virus (SHBBV) surveys exist, it cannot be assumed that they can be effectively administered outside of the population for which they were developed; validity depends on context.5 6 In the case of migrant populations, understanding of survey questions may be influenced by factors such as language proficiency, cultural belief systems and familiarity with different socio-political concepts and practices.7

According to Colbert and colleagues, ‘[w]hile numerous factors affect the quality of data derived from survey instruments … if different respondents do not understand questions in the same way and as researchers intended, then the other issues are moot’.8 Pretesting of survey instruments is ‘the only way to evaluate in advance whether a questionnaire causes problems’.9 However, there is a dearth of publicly available pretesting data in relation to SHBBV surveys in migrant contexts. At the time of writing, Q-Bank (a repository of survey question evaluation research) included pretest findings in relation to 11 hepatitis B and C items, 11 sexually transmissible infection items and 55 HIV items; yet, only one of these related to pretesting reported to have been conducted in migrant populations.10

If we are to advance the migrant SHBBV agenda, we must understand how best to obtain valid data. One method of achieving this is through conducting and publishing more pretest studies. In this article, we describe a project to develop and pretest a SHBBV KAP survey for migrants living in Australia. Consistent with the recommendations of the UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health, the project was undertaken as a collaboration between academics, policy-makers and front-line service providers.1

The aims of this paper are to: (1) describe the collaborative method used to develop and test an English-language SHBBV survey in diverse migrant communities; (2) summarise the problems identified through the pretest process and describe improvements made to the survey; (3) reflect on the adequacy of the pretest process; and (4) make recommendations to assist future researchers developing SHBBV surveys for migrant populations.

Methods

The Project Steering Group comprised: researchers from five Australian universities; senior SHBBV policy-makers from six government agencies; representatives from six SHBBV community organisations; and staff from six multicultural organisations (MO)/agencies. The Project Steering Group agreed to focus on migrants from three priority regions based on available epidemiological data; these regions were sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), South East Asia (SEA) and North East Asia (NEA).

With input from other Project Steering Group members, the researchers drafted an online and paper-based English-language survey, drawing on their expertise in sexual health, survey methodology and migrant community engagement in developing the instrument. In addition to searching the Q-Bank repository, as described in the Background, researchers reviewed other SHBBV surveys administered to migrant populations as identified in a scoping review by Vujcich et al.11 Online supplemental appendix S1 details the source of the questions included in the initial draft survey, and rationales for any amendments made by the researchers during the expert review phase.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp001.pdf (138.8KB, pdf)

Researchers also drafted a pretesting protocol (online supplemental appendix S2) which was based on the hybrid qualitative method developed by Oremus et al.12 The hybrid method combines and adapts two traditional methods of pretesting—namely, focus groups (or ‘panels’) and cognitive interviews. In focus groups, participants are brought together and researchers ‘collect data on what participants think about [a] topic and how participants collectively discuss the topic’.13 The strengths of focus groups include the potential time and resource efficiency associated with collecting data from a group of participants at the same time, as well as the ability to generate rich and nuanced data through interactions between people with different perspectives and experiences.13 14 However, it has been noted that the interactions between focus group participants can result in discussions leading in directions that are unrelated to the main research question.15 Consequently, the hybrid model incorporates a semistructured list of questions designed to ensure that data collection is focused and structured. The questions reflect a cognitive interviewing technique, and the moderator uses ‘probes’ designed to ‘reveal the thought processes involved in interpreting a question and arriving at an answer’,9 in addition to attitudes toward survey instructions, and survey appearance. Consistent with the approach adopted by Oremus et al, participants were ‘asked to provide comments about the questionnaire, rather than to provide personal responses to the survey question’.12 Given the sensitive subject of the survey, moderators made it clear to participants that they were not encouraged to reveal information about their own sexual practices or preferences.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp002.pdf (191.2KB, pdf)

Pretesting was conducted from February to August 2020. Variations were made to the study design described in the protocol as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, where face-to-face panel sessions were not possible, data were collected either through online videoconference technology or through one-on-one interviews.

MO on the Project Steering Group led participant recruitment and data collection processes on the basis of their knowledge of, and experiences working with, the target populations. Participants living in Australia were eligible for recruitment if they were: (1) over the age of 18; (2) born in SSA, SEA or NEA; and (3) proficient in reading and speaking English. Organisations were encouraged to recruit people with a view to maximising sample diversity regarding age, gender, country of origin and length of residency. Methods of recruitment comprised direct invitation (by email, telephone, in person and using social media platforms) and promotion through print and social media (eg, newsletters, Facebook). All participants provided written consent and received a $30 (Australian dollars) gratuity.

The first and second named authors and MO employees collected the data from the pretest panels. The MO employees were men and women who were born outside of Australia and had experience working with culturally and linguistically diverse populations, although not all had prior research experience. Researchers developed structured interview schedules predominately comprising meaning-oriented and paraphrasing probes (online supplemental appendix S3, versions (a)–(e)). Additionally, researchers developed a training manual and a prerecorded presentation to familiarise MO employees with data collection methods and ethical guidelines. Training topics included informed consent, group moderation techniques, probing strategies, distress protocols, confidentiality and academic honesty. MO managers worked through these materials with their employees to check understanding, present opportunities for discussion and role play, and incorporate local expertise around effective ways of engaging with participants. In some cases, MO employees had previously met participants through their involvement in the communities from which they were recruited.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp003.pdf (72.1MB, pdf)

Pretesting occurred in three rounds either face-to-face in private areas of community centres/work places or online. This iterative approach is recommended to ensure that any identified problems are addressed in survey revisions, and to check that revisions do not introduce new issues (data saturation).12 Panel sessions and interviews generally lasted between 1 and 2 hours; each was recorded and transcribed verbatim except in two instances in which technical problems were encountered and written notes were instead relied on; these are clearly indicated in the findings. Both the paper and online versions of the survey were pretested in each round.

At the conclusion of each round, a content analysis was performed. Two researchers independently coded the panel/interview transcripts and written notes (where transcripts were unavailable for reasons set out above) using the coding classification system developed by Forsyth et al (online supplemental appendix S4).16 17 The scheme comprises 28 categories, grouped according to the nature of the problems identified (ie, question content, question structure, reference, memory retrieval, judgement and evaluation, response terminology, response units, response structure and other). The coded transcripts were compared and coding differences were discussed and resolved by consensus.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp004.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

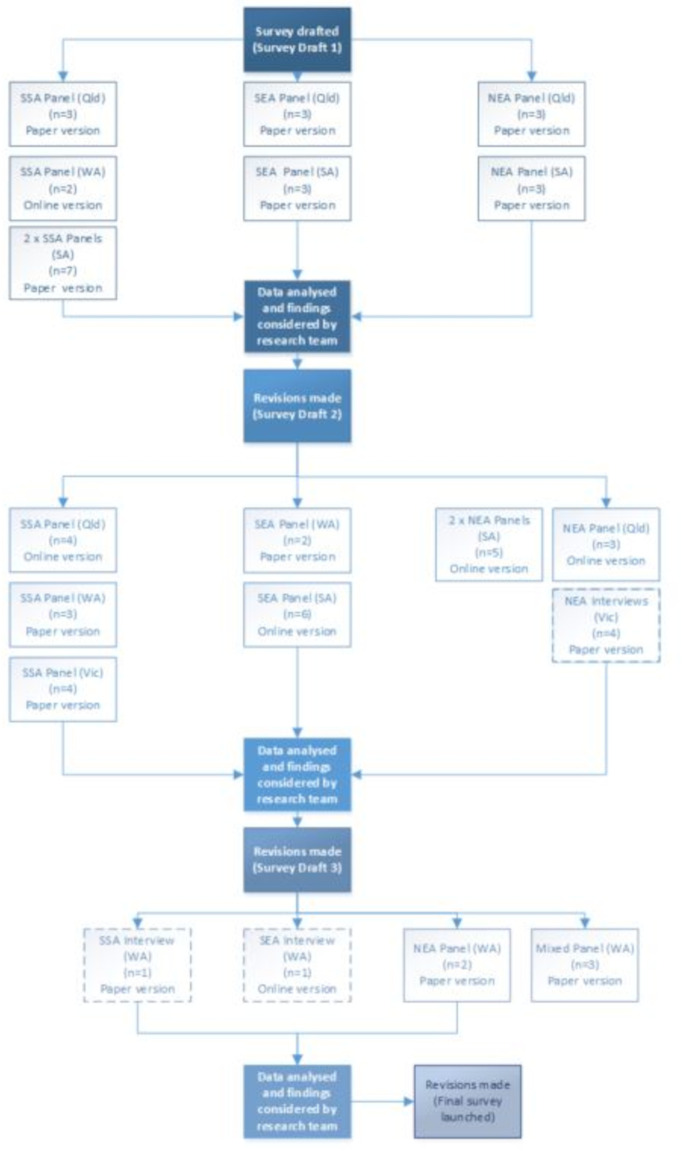

At the end of each round of pretesting, the first-named author presented each member of the research team with: (1) the text of each survey item; (2) a summary of pretest findings relating to each item, including key quotations; and (3) a recommendation as to whether a revision should be made to the question and, if so, the nature of the proposed amendment. Each member of the research team indicated whether they agreed or disagreed with each recommendation. Changes were adopted if a majority of the participating members of the research team supported an amendment. The pretesting process is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Survey pretesting process. NEA, North East Asia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; SEA, South East Asia; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa; Vic, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

MO employees involved in the pretesting provided feedback on the data collection process through reflection forms and email correspondence. The first and second authors independently coded the qualitative data using a coding framework developed by the first author. Coding decisions were compared and any differences were resolved by consensus following discussion.

The adequacy of the pretest process was also assessed by analysing feedback on the final English survey (at the time of writing, 150 English language surveys had been completed). Basic descriptive statistics were used to analyse Likert-scale responses to the statement ‘I found it hard to understand some questions/words’. Responses to an open field question (‘Do you have any other comments or feedback about this survey?’) were also summarised.

Patient and public involvement

Participant checking of transcripts or findings did not occur for logistical reasons, but community representatives in the form of MO employees were involved in study design, data collection, analysis and reporting.

Results

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the participants in each pretesting round are summarised in table 1 (see online supplemental appendix S5 for details of the number of individuals who were approached and agreed to participate in each round). In total, 62 participants pretested the survey (n=24 in round 1, n=31 in round 2, n=7 in round 3) across the four participating Australian states. Participants were born across three regions, with 25 from SSA, 17 from SEA and 20 from NEA. Ages ranged from 18 to 59 years (M=35·3; SD – 11·7), with 70% of participants identifying as women. The time participants had spent in Australia ranged from 1 to 29 years (M=8.9, SD – 6·8).

Table 1.

Pretest participants, by selected characteristics and data collection round

| Participant characteristics | Round 1 (n=24) |

Round 2 (n=31) | Round 3 (n=7) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 6 | 7 | 0 |

| 25–29 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

| 30–34 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 35–39 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| 40–44 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 45–49 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 50–54 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 54–59 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Regions of birth, and countries | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 12 | 11 | 2 |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Liberia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Rwanda | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Malawi | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Burundi | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Tanzania | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| South Sudan/Sudan | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Kenya | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Uganda | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eritrea | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Congo (Republic and Democratic Republic) | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Zimbabwe | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Zambia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Ghana | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| South-East Asia | 6 | 8 | 3 |

| Cambodia | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Thailand* | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Myanmar (Burma) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Singapore | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| North-East Asia | 6 | 12 | 2 |

| China | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Hong Kong | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Japan | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Taiwan | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Korea (North and South) | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| State of residence | |||

| Queensland | 9 | 7 | 0 |

| South Australia | 13 | 11 | 0 |

| Victoria | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Western Australia | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 15 | 22 | 6 |

| Male | 9 | 9 | 1 |

| Length of time in Australia (years) | |||

| Less than 2 years | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 2–4 | 4 | 14 | 2 |

| 5–9 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 10–14 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| 15 + | 9 | 5 | 1 |

Note: the Thai participant in round 1 was born in USA but lived in Thailand from the age of 5 months until migrating to Australia.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp005.pdf (122.1KB, pdf)

Pretest findings

The complete findings from each round of pretesting are available in online supplemental appendix S6 and online at https://www.mibss.org/publications. The main issues identified in round 1 related to the use of ‘vague’ or ‘undefined terms’ in the draft survey. As shown in table 2, terms which were identified as problematic included:

Table 2.

Examples of problems identified in round 1 survey items and resulting revisions

| Survey item | Round 1 feedback | Revised survey item (for round 2 pretesting) |

| Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an anti-HIV medication people can take to stop HIV transmission before they have, for example, condomless sex. What do you know about PrEP? (Tick one) □ It’s available in Australia now. □ It will be available in Australia in the future. □ I’ve never heard about it. |

Vague terms (code 7): ‘condomless’: Can I ask a question? What is the meaning of condom-less? (Participant, SSA, SA) | Are there any medicines that people can take BEFORE SEX to protect themselves against HIV? (Yes/No/I don’t know) |

| Complex topic (code 5): I’m a little bit confused with that. I’m not sure whether like normal people can take it. And then they can have sex but like how won’t they get HIV. Or HIV person can take it and then they have sex and then it won’t be infected to others. I’m not really understanding this (Participant, SEA, Qld). | ||

| (Tick if true) Some STIs can lead to infertility (inability to have a baby) | Vague terms (code 23): ‘infertility’: I picked that one because I was thinking like maybe some STIs … have an effect on the baby, so maybe some people have to not have the baby just in case (Participant, SSA, Qld). | Can some STIs make it harder for women to get pregnant? (Yes/No/I don’t know) |

| (Tick if true) It is not possible to get an STI through oral sex | Undefined terms (code 22): (I)n our communities, especially in African communities, I’m not sure if this practice is – it shouldn’t be relevant… For – I don’t know in other cultures, but – maybe by imitating what they see on pornography or something, but it’s not in the culture to do that thing, or on the mouth … those who don’t know, don’t practice this, cannot – ‘is it possible?’ Instead of putting the opinion, they ask the question, ‘Is – does this exist? | Question deleted |

| (Tick if true) There are effective treatments for hepatitis B. Source: Based on Sande, Validated a survey tool to measure knowledge, attitudes and behaviours about blood borne viruses and sexually transmissible infections amongst migrants from Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Northeast Asia living in Australia (unpublished thesis 2018). |

Vague terms (code 23): ‘effective treatments’: (H)ow you judge the effective treatment … To me, it’s 100% cure (Participant, NEA, Qld). | Is there a medicine that can cure hepatitis B (get rid of the virus completely from the body)? (Yes/No/I don’t know) |

| Imagine that next week you visit a general practitioner (GP doctor) because you are feeling a bit unwell. Would you ask for an STI and/or BBV test? (Tick one) | Erroneous assumption (code 12): If it’s not that serious, usually people wouldn’t go to see a GP (Participant, SSA, SA). | Question deleted |

| Which of the following best describes the most recent person you had sex with? ‘Regular sexual partner’ means someone you have an ongoing sexual relationship with (you expect the relationship to continue and to have sex with the partner again). This could be a husband, wife, de factor, boyfriend, girlfriend. □ Male regular sexual partner □ Female regular sexual partner □ Male casual sexual partner □ Female casual sexual partner □ Other type of partner (please specify) |

Vague terms (code 7): Facilitator: What would you define as a regular partner? So, if I say how many times would you have sex with a regular partner, what does regular mean? Participant: Every day (Participant, SSA, SA). |

Which of the following best describes the MOST RECENT person you had sex with? (Tick one)

|

| Vague terms (code 7): Say, for example, for the people who have a homosexual people. That’s why say that other type of partner (Participant, SSA, Qld). | ||

| Are you…? (Tick one) □ Male □ Female □ Another gender (please specify) |

Vague terms (code 23): Yes, I think something to do with another gender, it’s very difficult to understand. You ask another gender – what do you mean by that? Someone will ask, ‘What do you mean by that?’ So I don’t think it’s necessary to – but there’s a reason behind it? (Participant, SSA, SA). | How do you currently describe your gender identity? (eg, man, woman, transgender)

|

| Another gender interpreted to mean ‘homosexual’ (Participant, SSA, WA) |

BBV, Blood-borne Viruses; GP, General Practitioner; NEA, North East Asia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; SEA, South East Asia; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa; STI, Sexually transmissible infections; WA, Western Australia.

bmjopen-2021-049010supp006.pdf (670.8KB, pdf)

subjective adjectives/concepts such as ‘regular’ and ‘effective’;

defined technical/medical terms such as ‘pre-exposure prophylaxis’ (PrEP) and ‘infertility’, and

terms that may have been unfamiliar to people with low health literacy, people from different cultural backgrounds or people for whom English was a second language; examples were ‘condomless’, ‘oral sex’ and ‘gender’.

Problems were identified for both original survey items and those which had been previously validated or were adapted from existing surveys.

For several items (eg, items 1, 2 and 5 in table 2), no further issues were identified following item revision at the conclusion of round 1. However, some items continued to raise issues at each stage of the pretesting process. For instance, round 1 pretesting revealed that some participants understood the following statement—‘There are effective treatments for hepatitis B’—to mean that a cure was available, in contrast to the intended meaning (ie, that medications are available to limit disease progression). In response, the item was revised to test the extent to which respondents believed that a complete cure was available – ‘Is there a medicine that can cure hepatitis B (get rid of the virus completely from the body)?’ In round 2, pretesting demonstrated that the term ‘cure’ was also being misunderstood: ‘I think ‘cure’ means to me that living without symptoms’ (Participant, NEA, South Australia (SA)). The question was then amended to remove the term cure. During round 3, a further problem was identified in that participants were unsure whether the reference to ‘medicine’ included herbal/natural medicines; this resulted in the item being further revised to refer to ‘non-traditional medicine’. Further examples of items that underwent iterative amendments are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of changes to items, based in pretesting feedback in each round

| Survey version 1 | Pretesting feedback (round 1) | Survey version 2 | Pretesting feedback (round 2) | Survey version 3 | Pretesting feedback (round 3) | Final |

| (Tick if true) If someone is taking HIV medicine, it is unlikely that they will pass HIV onto someone else during sex. | Vague terms (code 23): ‘unlikely’ (Participant, SSA, WA) | Is it safe to have sex with someone who is taking HIV medicine daily and has undetectable (very low) amounts of the virus in their blood? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | Vague topic / unclear question (code 4): I think you need to put in whether that person is using condoms (Participant, NEA, Vic). | Is it safe to have sex without a condom with someone who has VERY LOW amounts of HIV in their blood? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | N/A | No Change |

| Complex topic (code 5): I’m a bit confused about undetectable amounts of virus (Participant, SEA, SA). | ||||||

| (Tick if true) People with HIV can live long and healthy lives in Australia. | Vague terms (code 23): Participants suggested adding a qualifier (‘if they take medication’) (Participant, SSA, WA). | Can people with HIV live healthy lives if they take their medication? | Vague topic / unclear question (code 4)—‘healthy lives’: Healthy lives—basically they’re talking about absence of disease (Participant, SSA, Vic). | Is there medication available for people living with HIV so they can live a normal life? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | Undefined / vague terms (code 7)—‘medication’: Maybe there’ll be some people who might think there might be herbal or traditional medicine that can help protect them (Participant, SEA, WA). | Is there non-traditional medication available for people living with HIV so they can live a normal life? |

| Erroneous assumption in question (code 12): The assumption is that medication is there, I think (Participant, SSA, Vic). | ||||||

| Undefined / vague term in question (code 7)—‘medication’: I just know the medication called PP (Participant, NEA, Vic) | ||||||

| What would you think if the doctor offered you STI and BBV tests during an appointment without you requesting any of these tests? (Tick one) | Wrong/mismatching units (code 24): I think the question should be how would you feel … because ‘offended’ … it’s a type of feeling (Participant, NEA, SA). | How would you feel if a doctor offered you STI and BBV tests during an appointment without you requesting any of these tests? | Complex topic (code 5): it’s hard to imagine what I will be feeling when it happen… because there are so many different considerations like if I just suddenly suggested by the doctor. Or I went there on purpose and then doctor suggest. So it’s just like, so I don’t know what I will feel (Participant, NEA, SA). | No change | Vague topic / unclear question (code 4): is the questions for health care only in regards to Australia or in regards to the countries that we come from? … different countries have different ways of asking people (Participant SEA, WA). | How would you feel if a doctor in Australia offered you STI and BBV tests during an appointment without you requesting any of these tests? |

| (Tick if true) There is a vaccination for hepatitis B. | N/A | Is there a vaccination for hepatitis B? | Undefined / vague term in question (code 7)—‘vaccination’: I don’t know whether it’s possible in research like this one to explain some of the words that are frequently used like ‘vaccination’ … Yeah, because quite a number of people think that any injection is vaccination (Participant, SSA, Vic) | Is there a vaccine (injection) to stop people from getting hepatitis B? | N/A | No change |

| (Tick if true) There are effective treatments for hepatitis B. | Vague terms (code 23): ‘effective treatments’: (H)ow you judge the effective treatment … To me, it’s 100% cure (Participant, NEA, Qld). | Is there a medicine that can cure hepatitis B (get rid of the virus completely from the body)? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | Vague terms (code 7)—‘cure’: I think cure means to me that living without symptoms, and without risk of transmitting to other people (Participant, NEA, SA). | Is there a medicine that can make the hepatitis B virus completely go away from a person’s body? (Tick one) | See comment above regarding the need to distinguish between allopathic and other medicines. | Is there non-traditional medicine that can make the hepatitis B virus completely go away from a person’s body? (Yes/No/I don’t know) |

|

Which of the following statements best describes your sexual feelings at the moment? (Tick one) I am attracted to … □ Only people of the opposite gender □ People of any gender □ Only to people of my own gender □ Not sure □ I prefer not to say |

Complex or awkward syntax in response (code 28): It’s a bit confusing to me (Participant, SEA, Qld). |

Which of the following types of people are you attracted to at the moment? (Tick as many as apply) □ Men □ Women □ Transgender people □ Not sure □ I prefer not to say |

Vague terms (code 7)—‘attracted’: Is it just, usually, having coffee with, or is it usually feel sexually something (Participant, NEA, SA). |

Which of the following types of people are you sexually attracted to at the moment? (Tick as many as apply) □ Men □ Women □ Transgender people □ Not sure □ I prefer not to say |

N/A | No change |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

NEA, North East Asia; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Australia; SEA, South East Asia; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa; Vic, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

A final subset of items elicited feedback during pretesting but did not result in amendments to the survey instrument. For instance, in response to the question ‘In the past 12 months, how many people have you had sexual intercourse with (vaginal or anal)?’ one respondent suggested that the term ‘sexual intercourse’ should be changed to ‘people you have slept with’ in order to be ‘a bit more culturally responsive’ (Participant, round 2, SSA, Victoria). Another respondent argued that reference to ‘anal sex’ was too sensitive: ‘we don’t talk about sex in the anus because it’s … an abomination’ (Participant, round 2, SSA, Western Australia (WA)).

Feedback on the final version of the survey

Of the 77 survey respondents who responded to the survey experience question, 16 (21%) agreed and 2 (3%) strongly agreed with the statement ‘I found it hard to understand some questions/words’ (table 4).

Table 4.

Responses to the statement in final survey (‘I found it hard to understand some questions/words’), n=149

| Response | Number of respondents (%) |

| Strongly agree | 2 (1.34) |

| Agree | 16 (10.74) |

| Disagree | 34 (22.82) |

| Strongly disagree | 25 (16.78) |

| Missing responses | 72 (48.32) |

Open field responses to the survey feedback question reveal that respondents still found some survey items unclear despite the fact that: (1) there had been iterative revisions to the items in response to pretesting data; or (2) no issues had been identified during the pretesting process. These responses are presented in full in table 5.

Table 5.

Responses to the question in the final survey (‘Do you have any other comments or feedback about this survey?’), by survey item

| Final survey item | Comments provided in response to feedback question |

| Is it safe to have sex without a condom with someone who has VERY LOW amounts of HIV in their blood? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | ‘very low’—what is very low? undetectable? Or very low as in being said by someone prior to having sex? |

| Is there non-traditional medication available for people living with HIV so they can live a normal life? | The statements about non-cultural medicines and/or non-traditional medicines were very confusing. Can you please be specific next time, Still not sure what was the rationale for this particular question. |

| Is there non-traditional medicine that can make the hepatitis B virus completely go away from a person’s body? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | |

| Is there a vaccine (injection) to stop people from getting hepatitis B? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | Some questions are not asked clearly, for example when you ask whether hepB can stop by vaccine, the answer will be different according to whether you mean completely stop or help to stop. |

| Can hepatitis B normally be passed on by sharing a toothbrush or shaving razor? (Yes/No/I don’t know) | The answer will be different too when you asked whether normally share shaves can transmit hepB. It would be better if you specified whether normally means there is no wound or cut on that person. |

| Which of the following types of people are you sexually attracted to at the moment? (Tick as many as apply) □ Men □ Women □ Transgender people □ Not sure □ I prefer not to say |

Shouldn’t use transgender as an attraction label … if anything it should be ‘men’, ‘women’ and ‘non-binary’ or add more options next time—that’s quite offensive actually* |

| *NOTE: This comment was made by the second person to complete the survey. The comment was actioned promptly through consultation with the support group TransFolk Western Australia. The question was amended as follows: To whom are you sexually attracted? (Tick all that apply): □ Women □ Men □ Non-binary people □ Others (please specify) □ I prefer not to answer | |

Reflections on the pretesting process

Reflecting on the pretesting process, some MO employees noted that the training materials were ‘prescriptive’ and ‘could be simpler and shorter’ (MO employee, Queensland (Qld)). In relation to the scripts that were used to guide data collection (online supplemental appendix S3), it was noted that ‘[s]ometimes the information needed on each question was a bit confusing’ (MO employee, WA) and that the scripts were ‘quite complicated to follow’ (MO employee trainer, Qld). The value of providing MO employees with more opportunities to familiarise themselves, and become comfortable with, the pretesting process was emphasised.

Using MO employees to collect pretesting data was considered ‘extremely useful in contextualising the research questions for participants and eliciting their views’ (MO employee, SA). However, given the aim of maximising sample diversity, one partner observed that ‘it is very likely the [MO employees] and participants would come from different backgrounds thus accent of participants may affect understanding and discussions with each other’ (MO employee, Qld).

Discussion

Research rigour is compromised when survey data are accepted at face value without examining the extent to which researchers and participants have a shared understanding of survey items. This study demonstrates the importance of pretesting SHBBV survey instruments in migrant contexts. Numerous examples were presented in which participants did not understand items in the manner intended by the survey designers, including items that had been validated in other settings.

Writing in the context of multilingual surveys, Pan and Fond cited three specific errors that may affect data quality in translated surveys—namely (1) using inappropriate linguistic conventions or terminology, (2) failing to adhere to relevant cultural norms and (3) invoking concepts that do not reflect the social practices of the target audience.18 Each of these issues was identified in our pretesting process (table 6), suggesting that Pan and Fond’s approach is also relevant to monolingual surveys conducted in culturally and linguistically diverse migrant populations.

Table 6.

Examples of Pan and Fond survey errors identified in pretesting data

| Error | Examples |

| Inappropriate linguistic conventions or terminology | ─ ‘condomless sex’ ─ ‘vaccination’ ─ ‘treatments’ / ‘cure’ ─ ‘another gender’ ─ ‘undetectable (very low) amounts of virus’ ─ ‘in exchange for sex’ |

| Failing to adhere to cultural norms | ─ Impolite to ask age in some cultures ─ Reference to ‘anal sex’ considered problematic by some respondents |

| Invoking concepts that do not reflect the social practices of the target audience | ─ The scenario-based question in which participants were asked to ‘imagine that next week you visit a general practitioner because you are feeling a bit unwell’ was not considered to be realistic; participants would only visit a doctor for serious illnesses ─ The term ‘medicine’ could be interpreted by participants as allopathic medicine and/or traditional/herbal medicine |

In addition to demonstrating the importance of pretesting to identify problems in migrant health surveys, this study offers some guidance as to how future pretesting ought to be conducted in cross-cultural contexts. As Aizpurua has observed, ‘despite the increased use of pretesting methods in [multinational, multiregional, and multicultural] surveys, there remains no consensus regarding best practices for their design and implementation.’19 We offer the following lessons for each stage of the pretesting process:

Design

The current literature provides little guidance as to the optimal sample size for pretesting. Ruel and colleagues offer a wide range of 12–50 as the ‘rule of thumb’.20 Our findings suggest that larger pretesting samples may be needed, particularly where: (1) multiple survey formats are being tested (eg, online and paper); (2) the target population includes many culturally and linguistically diverse groups; and (3) survey revisions are being made between rounds of pretesting. While issues continued to be identified until our last round of pretesting in a sample of 62 participants, further data collection was not feasible. Future survey researchers and project funders ought to be mindful of the time and resources needed to conduct rigorous pretesting. We repeat previous calls for ‘additional research examining appropriate sample size and numbers of iteration rounds in cross-cultural research with groups featuring various levels of homogeneity.’19

Researchers should also consider whether the pretesting process needs to allow for different survey instruments to be produced for different cultural groups. Our pretesting process was designed with the a priori aim of producing a single English survey to be administered to all migrant groups (while the English survey was then translated into multiple languages, the description of the translation process lies beyond the scope of this article). Although the pretesting results did not suggest the need for different versions of the English survey to be designed for different communities, researchers in other studies may need to carefully consider whether the pretesting process should be designed to allow for multiple versions of the survey to be developed for different groups. There are many examples of survey content that may need to be presented differently for different cultural groups, including measurements (eg, imperial/metric), references to institutions (eg, Parliament/Congress) and date conventions (eg, day/month first) and customs.21

When pretesting migrant health surveys, the significance of intersectionality must not be overlooked. Each community will have its own subcommunities who may have quite different understandings of health and practices. Our sampling strategy did not focus on purposively recruiting people representing a sufficient range of gender expressions (eg, non-binary people, transgender men and women). As a consequence, problems were identified with the wording of the gender identity question after pretesting was completed. It is clear that ‘culture’ and ‘country of origin’ are not the only factors that influence the migrant health experience, or the manner in which migrant health survey items are interpreted and answered.22 Further evidence of this may be found in the fact that validated items that had been acceptable in other migrant settings (eg, PrEP question from the Sydney Gay Asian Men Survey23) did not test well in our broader sample.

Data collection

The present study recruited participants with English proficiency to test an English-language survey. However, it was observed that some participants for whom English was not a first language either struggled or were reluctant to provide feedback. Reasons for this may include lack of confidence, or an actual or perceived inability to invoke the linguistic tools (eg, grammar, lexis and phonological systems) needed to express complex or unfamiliar concepts, particularly in a group setting.24 Moreover, it was often difficult to discern whether some problems (eg, difficulties understanding the phrase ‘undetectable (very low) amounts of virus’) were related to English-language proficiency or health literacy, or some combination thereof. Where feasible, future migrant health researchers should enable participants to engage in pretest discussions in their first language (even when it is different to the language of the survey being tested). Although MO employees with experiences of migration were used to collect data in this study, they were not proficient in all of the first languages spoken by participants. Additionally, panels frequently comprised a mix of participants who did not speak the same first language. Using bilingual workers to facilitate pretest panels among migrants from a common linguistic background may help to overcome these limitations.

It is feasible to use bicultural/bilingual workers to collect pretesting data. This approach to data collection goes some way to overcoming the ‘othering’ of migrant communities in health research, and recognises the importance of ‘cultural wisdom’ in collecting meaningful data in cross-cultural contexts.25 More attention should be given to ensuring that bicultural workers are both involved in the design of pretesting studies and are adequately trained to collect pretesting data.

Data analysis and survey revision

Oremus et al suggest that survey revisions should be based on ‘[r]ecurring comments that were mentioned at least once during each pretest panel, or a single comment … mentioned during one pretest panel and subsequently validated by a majority of the panel’s participants’.12 However, our pretesting experience suggests that greater flexibility and researcher discretion is needed. For example, some participants insisted that references to anal sex should be removed on the basis that the practice was culturally taboo. The feedback was not incorporated into survey revisions because the researchers recognised the need to be inclusive of a range of sexual practices. While survey pretesting results are important, they need to be interpreted in the context of other factors relevant to the research process, including ethics and overall research aims.

Our data demonstrate the value of iterative (multiround) pretesting. There were several examples of items which were revised in response to one round of pretesting but gave rise to new issues in subsequent rounds. However, in demonstrating the importance of a ‘pretest-revise-repeat’ process, our findings are also consistent with previous studies which have shown that survey researchers are ‘not particularly successful in improving questions that pretesting identified as problematic.’16 Survey researchers and those who use survey data to make policy and planning decisions must not mistake a pretested survey for a perfect survey. Survey quality improvement is a continuous process and must extend beyond the pretesting phase. One strategy we adopted is to collect and analyse participant feedback on the final version of the survey with a view to using the feedback to: (1) help analyse the survey data and highlight relevant limitations; and (2) inform future iterations of the survey tool. Additionally, this study forms part of a pilot to investigate the feasibility of designing and administering a national, periodic survey of migrant SHBBV KAP in Australia. The survey will be piloted with approximately 1600 participants and quantitative data analysis will be used to inform future revisions of the instrument. For instance, high proportions of skipped questions, ‘I do not know’ responses or failure to follow skip logic instructions may signal the need for further amendments to content, item wording or instructions.

Despite the systematic approach to pretesting adopted in this study, limitations remain. For instance, men were underrepresented in the pretesting sample; although men born in non-main English speaking countries tend to have higher English proficiency levels than women migrants in Australia, there is evidence to suggest that women migrants may have higher levels of health literacy in relation to subjects such as sexually transmissible infections and contraception.26 27 Additionally, the sensitivity of some survey items and the group nature of the data collection process may have resulted in some participants being reluctant to express their opinions, notwithstanding that participants were not required to reveal information about their own sexual practices or preferences. Finally, amendments introduced in response to round 3 were not able to be pretested due to time and resource limitations. Feedback received on the final piloted survey reveals that some round 3 amendments (eg, the introduction of the term non-traditional medicines) would have benefited from further pretesting.

The single most important step that the research community can take to improve the quality of migrant health survey data generally, and SHBBV data in particular, is to conduct and publish more pretesting studies.19 The more data are available, the more we can learn about ways of improving pretesting methods and survey drafting practices. However, this recommendation cannot be realised until structural barriers are addressed. Those who fund survey research for policy and planning purposes must make allowances for the time and costs associated with undertaking rigorous pretesting. Moreover, journals must review editorial policies around word limits and the publication of supplementary data, and require survey researchers to adequately describe their pretesting processes and make pretest findings publicly available.8 28

Reflecting on the recent debate around the reliability of some systematic reviews, Horton invited us to ‘[i]magine if the entire edifice of knowledge in medicine was built on a falsehood’.29 So too, the general lack of published findings on SHBBV survey pretesting in migrant contexts must cause us to at least question the validity of the data being currently used to inform policy and planning decisions. Until this research gap is addressed, our ability to work towards the goals of the UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health will be compromised.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DV, MR, GB, JD, LH, RL, LM, AM, BO and AR designed the study. DV, MR, JD, ZG and EO performed data collection. DV, MR, RL and AR coded the data and verified results. DV drafted the manuscript and is the guarantor, and MR, GB, JD, ZG, LH, RL, LM, PM, AM, BO, EO and AR were involved in critical revisions for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project was funded by the Australian Research Council, Curtin University, Shine SA and health departments in Queensland (Qld), Western Australia (WA), South Australia (SA) and Victoria (Vic). Health departments had input into study design as part of the Project Steering Group but no input in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data queries can be addressed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained for this study (Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee 2019–0395).

References

- 1.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunaratnam P, Heywood AE, McGregor S, et al. HIV diagnoses in migrant populations in Australia-a changing epidemiology. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212268. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernando V, Alvárez-del Arco D, Alejos B, et al. HIV infection in migrant populations in the European Union and European economic area in 2007–2012. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 2015;70:204–11. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Seeking feedback to develop a population-representative sexual health survey instrument: an open call from the WHO—Additional information for participation, 2019. Available: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1f33Eustjgoqq4cY34kknc9UMvw_NIP3c/view [Accessed 15 Oct 2020].

- 5.Griffee D. Questionnaire translation and questionnaire validation: are they the same? 2001. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED458800

- 6.Kaladharan S, Daken K, Mullens AB, et al. Tools to measure HIV knowledge, attitudes & practices (KAPs) in healthcare providers: a systematic review. AIDS Care 2021;33:1500–6. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1822502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspar R, Peytcheva E, Yan T. Pretesting. In: Guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Centre, 2016. http://ccsg.isr.umich.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colbert CY, French JC, Arroliga AC, et al. Best practice versus actual practice: an audit of survey pretesting practices reported in a sample of medical education journals. Med Educ Online 2019;24:1673596. 10.1080/10872981.2019.1673596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Presser S, Couper MP, Lessler JT, et al. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opin Q 2004;68:109–30. 10.1093/poq/nfh008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention . Q-Bank: improving surveys through collaboration. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/QBank/Home.aspx

- 11.Vujcich D, Wangda S, Roberts M, et al. Modes of administering sexual health and blood-borne virus surveys in migrant populations: a scoping review. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236821. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oremus M, Cosby JL, Wolfson C. A hybrid qualitative method for pretesting questionnaires: the example of a questionnaire to caregivers of Alzheimer disease patients. Res Nurs Health 2005;28:419–30. 10.1002/nur.20095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cyr J. An integrative approach to measurement: focus groups as a survey pretest. Qual Quant 2019;53:897–913. 10.1007/s11135-018-0795-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan DL. Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol 1996;22:129–52. 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tausch AP, Menold N. Methodological aspects of focus groups in health research: results of qualitative interviews with focus group moderators. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2016;3:1–12. 10.1177/2333393616630466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsyth B, Rothgeb J, Willis G. Does pretesting make a difference? An experimental test. In: Methods for testing and evaluating survey questionnaires. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2004: 525–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothgeb J, Willis G, Forsyth B. Questionnaire pretesting methods: do different techniques and different organizations produce similar results? Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 2007;96:5–31. 10.1177/075910630709600103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y, Fond M. Evaluating multilingual questionnaires: a sociolinguistic perspective. Survey Research Methods 2014;8:181–94 https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Evaluating-Multilingual-Questionnaires%3A-A-Pan-Fond/911649b303fc8c1c17aa6c61a952ab14a7a1a012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aizpurua E. Pretesting methods in cross-cultural research. In: Sha M, Gabel T, eds. The essential role of language in survey research. RTI press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruel E, Wagner W, Gillespie B. Pretesting and pilot testing. In: The practice of survey research: theory and applications. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2016: 101–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harkness J, Villar A, Edwards B. Translation, adaptation and design. In: Survey methods in multinational, multiregional and multicultural contexts. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010: 117–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapilashrami A, Hankivsky O. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. Lancet 2018;391:2589–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31431-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong H, Mao L, Chen T. Sydney gay Asian men survey: brief report on findings. 2018. Sydney: Centre for Social Research in Health, University of New South Wales, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gan Z. Understanding English speaking difficulties: an investigation of two Chinese populations. J Multiling Multicult Dev 2013;34:231–48. 10.1080/01434632.2013.768622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darder A. Decolonizing interpretative research: a criticial bicultural methodology for social change. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 2015;14:63–77 https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Decolonizing-Interpretive-Research%3A-A-Critical-for-Darder/171581247cd4b6322f7db97c60ecb87441d17ce9 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 3416.0 perspectives on migrants 2007 – migrants and English proficiency, 2008. Available: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3416.0Main%20Features52007

- 27.Kaczkowski W, Swartout KM. Exploring gender differences in sexual and reproductive health literacy among young people from refugee backgrounds. Cult Health Sex 2020;22:369–84. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1601772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med 2010;8:e1001069. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horton R. Offline: the gravy train of systematic reviews. The Lancet 2019;394:1790. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32766-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049010supp001.pdf (138.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049010supp002.pdf (191.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049010supp003.pdf (72.1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049010supp004.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049010supp005.pdf (122.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-049010supp006.pdf (670.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data queries can be addressed to the corresponding author.