Abstract

Introduction

Endometriosis can cause chronic pain and subfertility thereby negatively affecting quality of life (QoL). Surgical removal of endometriosis lesions leads to improved health-related QoL, although not to the level of QoL of healthy controls. Pain intensity and cognitions regarding pain can play a crucial role in this health-related QoL following surgical treatment. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a psychological treatment. In patients with chronic pain caused by a variety of medical conditions, CBT is effective in improving QoL. We designed a research protocol to investigate the effect of CBT on QoL in patients with endometriosis-associated chronic pain who are undergoing surgery.

Methods and analysis

This is a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial in which 100 patients, undergoing endometriosis removal surgery due to endometriosis-associated chronic pain, will be randomised between post-surgery usual care with CBT and post-surgery usual care only. Participants in the CBT group will additionally receive seven sessions of CBT, focused on expectancy management, cognitions regarding pain and emotional and behavioural impact of pain. To determine the primary outcome Quality of life, both groups will complete questionnaires assessing QoL. The secondary outcomes pain intensity, pain cognitions, fatigue and perceived stress are also measured using questionnaires. Additionally, a marker for stress (cortisol extracted from a hair sample) will be assessed at T0 (baseline assessment), T1 (post-intervention; 2 weeks after completion of all CBT sessions) and T2 (follow-up; 14 weeks after T1). Statistical analysis will be performed using SPSS software.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the region Arnhem-Nijmegen from the Radboud University Medical Centre on 2 September 2020. The findings of this study will be published in scientific journals and will be presented at scientific conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: surgery, gynaecology, pain management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A cognitive behavioural therapy protocol was developed specifically for this patient group to be used as intervention.

Patients are treated with cognitive behavioural therapy in addition to endometriosis reduction surgery.

There is a difference in contact time between therapists and patients in the intervention versus the control group.

Participants are not blinded for group allocation which could lead to bias.

Introduction

Endometriosis, the presence of functioning endometrium-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, is one of the most prevalent benign gynaecological conditions.1 It can cause chronic pain and subfertility and can lead to impaired quality of life (QoL). Although medical therapy can halt disease activity, surgical removal of endometriosis is often required. Unfortunately, pain symptoms remain present in approximately 50 per cent of the patients after surgery.2 Moreover, the level of health-related QoL remains lower compared with the QoL of healthy controls.3 Van Aken et al4 showed that pain intensity and pain cognitions including pain anxiety, catastrophising and hypervigilance towards pain are all independent factors contributing to health-related QoL in patients diagnosed with endometriosis. This indicates that modifying these cognitions via psychological intervention might improve QoL in patients with endometriosis. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based psychological treatment and is increasingly being recognised as an effective treatment to improve QoL in patients with various medical conditions.5 CBT uses a process called cognitive restructuring: a technique designed to teach patients how to identify, evaluate and re-label maladaptive thoughts, evaluations or beliefs that are suspected to be the root cause of one’s psychological disturbance.6 7 Cognitive restructuring should result in a more rational, realistic and balanced view of those unhelpful thoughts, evaluations or beliefs. The patient is furthermore expected to contribute to her own treatment process. This can be done by questioning maladaptive thoughts and behaviours about situations and by exposing herself to those situations to evaluate whether those thoughts and beliefs have come true. The therapist helps the patient to achieve treatment goals by sharing his expertise and support. This approach is named collaborative empiricism and is a key feature of CBT. It aims to result in the patient attributing her behavioural change to her own efforts leading to better and more persistent outcomes.6 7 To date, there are no studies available that describe the efficacy of post-surgical CBT to improve QoL in patients diagnosed with endometriosis. CBT has been used and proven effective in improving QoL and decreasing perceived pain intensity in other chronic pain conditions.8–10 We have recently shown that patients undergoing endometriosis surgery believe that CBT could be a valuable asset to their treatment, in order to improve QoL.11 We designed this research protocol for a randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy of CBT on improving QoL in patients with endometriosis-associated pain in addition to endometriosis removal surgery.

Methods

Participants, interventions, outcomes and intervention allocation

Study design

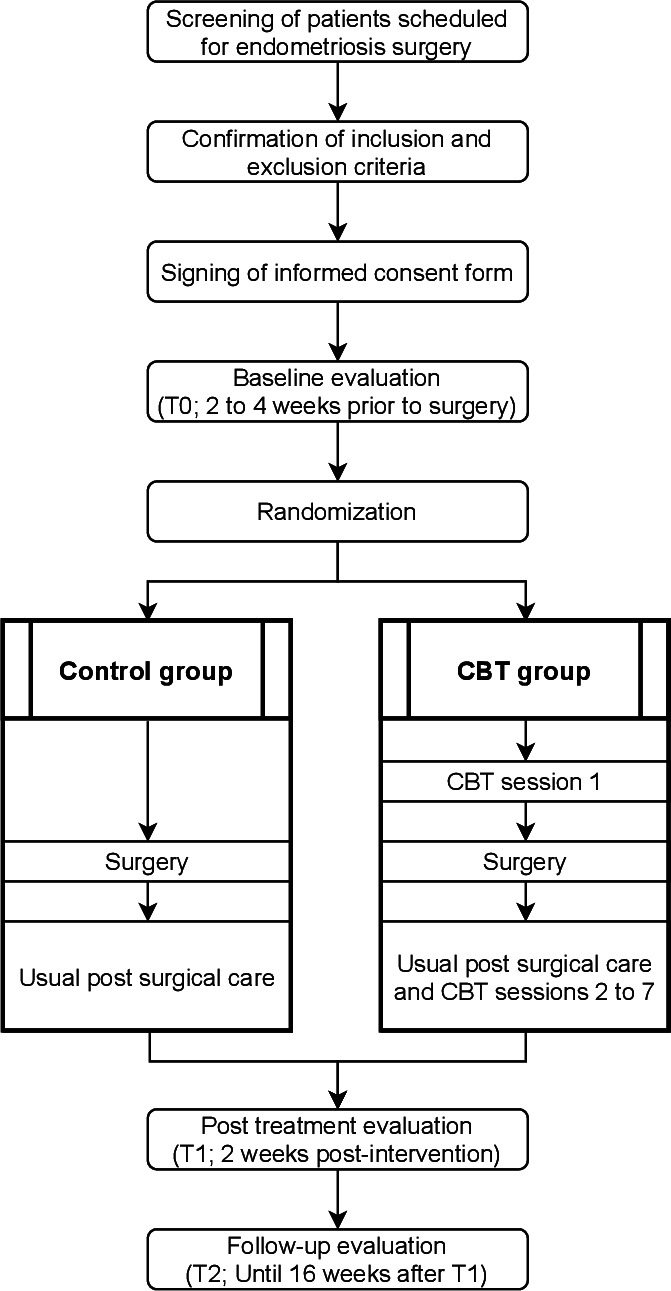

This is a research protocol for a randomised, controlled, prospective, single-blind (assessor) clinical trial in which patients undergoing surgery for endometriosis-related pain will be randomly allocated to surgery and usual care (control group) or to surgery and usual care plus CBT (CBT group). The participants and the psychologists delivering the intervention cannot be blinded due to the used intervention. Figure 1 shows an overview of patient flow throughout the study. This protocol was developed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials reporting guidelines.12

Figure 1.

Patient flow throughout the study. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy

Patient involvement

In 2019 and 2020, prior to developing this study protocol, we conducted a focus group study with patients who underwent endometriosis surgery to investigate if they were interested in psychological therapy in order to improve QoL in addition to endometriosis surgery and why.11 We furthermore explored how they would design such a psychological treatment. The information acquired in these focus groups was taken into account when designing the intervention used in this research protocol.

Sample size calculation

The calculation for the required sample size was performed for the primary endpoint QoL. There was no study available describing the effect size of CBT on QoL after endometriosis surgery which could be used in the sample size calculation. Therefore, we used a study in which the authors examine a cognitive behavioural intervention to improve QoL in patients undergoing surgery due to chronic back pain.13 Based on this article we expect to find medium to large effect sizes (Cohen’s d) of 0.75 and 1.35 (measured with the physical and mental component scales of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey) of postoperative CBT compared with usual care-only on QoL regarding physical and mental health, respectively. Based on literature we expect the dropout rate to be 15%–16%.14 15 However, due to the intensity of the intended intervention combined with surgery we anticipating patient dropout to be higher: 19%. Therefore, a total of 100 patients should be included to detect significant effects (α=0.05, power (1-β)=0.85).

Study population and recruitment

At the start of the study, subjects will be recruited in Rijnstate Hospital, Radboud University Medical Center and Catharina Hospital, all located in the Netherlands. In all hospitals, a multidisciplinary centre for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis is present, in which gynaecologists, surgeons and psychologists with extensive experience in treating women with endometriosis are involved. All centres are located in urban areas. All patients undergoing endometriosis removal surgery due to endometriosis-associated chronic pain will be referred by their gynaecologist to a researcher who will check whether they meet the inclusion criteria. Patients are eligible for this study when they are 18–50 years of age, diagnosed with endometriosis (proven by ultrasound, MRI or surgery) and have an indication for endometriosis surgery due to endometriosis-related chronic pain. An indication for surgery is present when hormonal and/or analgesic therapy failed in suppressing pain symptoms, is contra indicated due to comorbidity or has unacceptable side effects. Chronic pain is defined as pain existing longer than 3 months (in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases 11 formulated by the WHO16), with an average Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of four or higher in the month prior to inclusion (which will be asked at inclusion). Furthermore, participants should be able to read and write Dutch in order to be able to complete the questionnaires.

Because certain conditions require a different psychological approach,4 17–19 and therefore could influence the efficacy of the intervention used in this study, we exclude patients suffering from endometriosis-related infertility without pain, chronic pain that can be attributed to other diseases or syndromes, patients that are diagnosed by a psychiatrist or psychologist with a mood, anxiety or personality disorder (as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V20), are undergoing psychological therapy or use psychopharmacological medication aimed at altering mood (according to either patient or their physician) at the moment of inclusion. Because we will also assess cortisol levels in scalp hair, patients will also be excluded if they have scalp hair shorter than 4 cm.

Patients eligible for inclusion will be provided with detailed written and verbal information. Informed consent will be obtained by an authorised researcher if patients are willing to participate and all questions have been resolved. Patients can contact an independent researcher if they wish to discuss the study with someone who is not directly involved in the project but has knowledge about all aspects of this study. Participants can withdraw consent at any time without providing a reason.

Randomisation

Computerised randomisation will be conducted after inclusion and baseline assessment. Only an authorised researcher will be able to perform randomisation and have insight in randomisation results. No stratification factors will be used. This study is single blinded (the assessor is blinded for treatment allocation). Participants and psychological therapists cannot be blinded due to the used intervention. The randomisation code will be broken when a patient’s health is at risk or when investigation is required by the sponsor, the Medical Ethics Committee (METC) or the monitor, for example, to verify if the study is executed in accordance with the study protocol and national and international regulations.

Variables

Demographic variables will be recorded, including age, length, weight, body mass index, marital status, educational attainment, occupation, the method used to diagnose endometriosis, year of diagnosis, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification, type of endometriosis, use of contraception, use of analgesics, use of other medications, presence of subfertility, parity, history of DSM-V diagnosis and if patients underwent psychological treatment prior to inclusion in this study. An overview of these variables, including their corresponding values, is provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables

| Variable | Values |

| Age | Years |

| Length | Centimetres |

| Weight | Kilograms |

| BMI | Kg/m2 |

| Marital status | Single/married or living with partner/widow/separated |

| Educational attainment | Non-categorical text |

| Occupation | Student/employee/housewife/unable to work/unemployed |

| Method used to diagnose endometriosis | Ultrasound/MRI/Surgery |

| Year of diagnosis | Year |

| r-ASRM classification | I–IV |

| Type of endometriosis | Ovarian/peritoneal/deep |

| Use of analgesics | Yes (specify)/No |

| Contraception use | Yes (specify)/No |

| Use of other medications | Yes (specify)/No |

| Subfertility | Yes/No |

| Parity | Numerical |

| History of DSM-V diagnosis | Yes (specify)/No |

| Underwent psychological treatment prior to inclusion | Yes (specify)/No |

BMI, body mass index; DSM-V, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V; r-ASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

The primary endpoint in this study is QoL. In our opinion evaluating this outcome, that reflects an improvement that patients themselves experience in their daily lives, should have priority over other measurements (eg, pain score, laboratory results or absence of endometriosis lesions) that do not. QoL will be measured by two questionnaires: a general QoL questionnaire, the Dutch version of the Short Form 36 (RAND-36), and an endometriosis disease specific questionnaire, the Endometriosis Health Profile 30 (EHP-30). Both questionnaires measure QoL but do so differently. The EHP-30 is a disease-specific QoL questionnaire which is validated for use in patients with endometriosis21 22 and measures the impact of the disease on physical, mental and social aspects of life. The questionnaire is divided into two parts. The core questionnaire consists of five subscales: pain, control and powerlessness, emotional well-being, social support and self-image. The second part consists of six subscales: work, relationship with children, sexual intercourse, infertility, medical profession and treatment. Raw scores are transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, and a higher score corresponds with worse QoL. The validated23 questionnaire RAND-36 is used to measure general QoL. It is a multipurpose, general health survey which is applied to measure QoL on nine different domains: physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations due to physical health, role limitations due to emotional problems, emotional well-being, vitality, pain, general health and health change. Raw scores are transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, and a higher score corresponds with better QoL. The EHP-30 is a sensitive tool which is responsive to changes in health-related QoL in this specific patient group22 while the RAND-36 provides a complete QoL assessment which can be compared more easily with QoL of patients with other illnesses or healthy people.

Secondary endpoints are pain intensity, fatigue, pain-related cognitions including anxiety and catastrophising, perceived stress and cortisol level as a marker for stress. Pain-related cognitions have shown to be independent factors contributing to the health-related QoL of patients with endometriosis,4 therefore it is interesting to determine whether CBT influences these cognitions as well. Pain intensity is measured by the NRS, pain anxiety by the Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale and catastrophising by the Pain Catastrophising Scale. Additionally, fatigue is measured using the Checklist Individual Strength. Indicators for stress will be measured in two ways. First, perceived stress is measured by the Perceived Stress Scale questionnaire which measures self-reported stress levels in patients. In addition to perceived stress, stress can also trigger a response leading to an activation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis. Activation of this axis leads to the secretion of cortisol by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol modulates the immune system24 and is therefore essential for proper body and brain function in response to stress. Cortisol levels can be used as an indicator for the amount of stress. To date, cortisol levels are measured in saliva, serum or urine, representing a dynamic reflection of cortisol concentrations and stress reactivity at one single point in time. These types of measurements are easily affected by short-term changes of cortisol including the circadian rhythm or situational stress and are therefore less reliable to use as an indicator for chronic stress, which is present in patients with chronic pain including endometriosis. In order to use cortisol as a marker for chronic stress, it should be measured in another body specimen. Since recently, cortisol can be extracted from hair. Hair has an average growth rate of 1 cm/month and evidence of long-term stress exposure can be analysed in a string of hair. This makes hair cortisol a useful biomarker for chronic stress. In an earlier prospective follow-up study, researchers showed that hair cortisol levels are higher in patients with endometriosis as compared with healthy controls, and that hair cortisol levels correlate with QoL.25

All primary and secondary outcomes will be measured at baseline (T0) between 2 and 4 weeks prior to surgery, post-intervention (T1) approximately 2 weeks after completion of all CBT sessions and at follow-up (T2) approximately 14 weeks after T1. An overview of all outcome variables is provided in table 2. All questionnaires will be sent and returned through a web-based platform. The collection of the hair sample for cortisol measurements will be conducted by authorised and trained researchers. Analysis of the hair samples will be performed by a certified laboratory experienced in extracting cortisol from hair samples.

Table 2.

Outcome variables

| Outcome variable | Evaluation period | Measuring instrument | ||

| T0 | T1 | T2 | ||

| QoL* | × | × | × | EHP-30 and RAND-36 |

| Pain intensity† | × | × | × | NRS |

| Pain anxiety† | × | × | × | PASS |

| Catastrophizing† | × | × | × | PCS |

| Fatigue† | × | × | × | CIS |

| Subjective stress† | × | × | × | PSS |

| Marker for physiological stress† | × | × | × | Hair cortisol analysis |

*Primary endpoint.

†Secondary endpoint.

CIS, Checklist Individual Strength; EHP-30, endometriosis health profile 30; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PASS, Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale; PCS, Pain Catastrophising Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; QoL, quality of life; RAND-36, Short form 36.

Intervention

Control group

The control group will receive usual care. Usual care consists of pre-surgical counselling by the participant’s gynaecologist about the intended surgical procedure, possible complications and expected results. When indicated, patients will consult a gastrointestinal surgeon and/or a urologist from the endometriosis team. Surgery will be carried out, following medical standards, by members of a team of gynaecologists and, if indicated, together with gastrointestinal surgeons and/or urologists. Before and after surgery, patients will take their usual hormonal therapy to minimise menstrual cycle effects. Patients are allowed to use analgesics if necessary, but are asked to refrain from seeking (additional) psychological treatment when participating in this study. Patients will receive medical check-ups after approximately 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months post-surgery, consisting of history taking (in which symptoms and postoperative recovery will be assessed) and physical examination. They can contact the endometriosis nurse by email or phone at any time.

CBT group

In addition to the usual care as described above, patients in the intervention group will also undergo seven sessions of CBT. Therefore, a CBT protocol was developed by members of the research team consisting of gynaecologists experienced in treating women with endometriosis and of psychologists with experience in CBT, chronic pain and/or treating patients diagnosed with endometriosis. In order to develop a CBT protocol, we first performed a focus group study. In this focus group study we showed that patients who had been surgically treated for endometriosis expect that CBT could improve QoL and reduce pain.11 Patients in this study were exclusively interested in face-to-face sessions (either in-person or using a videoconference) instead of web-based therapy without personal contact. Patients noted however, that web-based sessions could positively contribute to face-to-face CBT by providing a detailed overview of all the information already introduced in the face-to-face sessions. They also noted that the psychologist administering the CBT sessions should have knowledge about endometriosis and the problems that are experienced by patients in their daily lives. There was no clear consensus among participants of the focus groups about other aspects such as the amount and duration of CBT sessions. Patients did stress however that their symptoms should be taken seriously. They did acknowledge that living with endometriosis might eventually negatively affect mental well-being but emphasised that those problems are a result of the physical aspects of endometriosis.

Taking these findings into account, we developed a CBT protocol specifically aimed at improving QoL in patients undergoing surgical treatment due to endometriosis-associated pain. Patients will receive one pre-surgery and six post-surgery individual face-to-face sessions of CBT. Face-to-face therapy can be in-person therapy or therapy using a videoconference. The used method depends on the participants’ choice or current restriction due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pre-surgery session is always in-person and will take place approximately 2 weeks prior to surgery. The post-surgery sessions will start 4 weeks after surgery and take place every 2 weeks. All sessions will be coordinated by registered psychologist (meaning at least 2 years additional post master education) who are experienced in CBT and have knowledge about endometriosis. The CBT protocol contains standardised information divided into separate sessions. Content of the CBT protocol is based on standard CBT interventions for chronic pain, supplemented with interventions aimed at specific issues present in patients with endometriosis, as described below. In the pre-surgery session, the therapy is introduced and the influence of endometriosis reports on the patient’s life is assessed. To improve treatment compliance and cognitions with respect to reports after surgery, expectations towards the psychological treatment and the operation will be managed. Furthermore, general psycho-education about pain is provided. In the six post-surgery sessions, psycho-education concerning the biological link between endometriosis-related pain and behaviour, as well as relaxation, relationship between emotions, thoughts and behaviour, ways to change thoughts and regulate emotions and hypervigilance will be addressed. Additionally, one session is dedicated to discuss possible issues concerning intimacy and sexuality, which are often affected in patients diagnosed with endometriosis. In the final session patients will evaluate the therapy together with the psychologist. Relapse prevention will be discussed too. An overview of each session is provided in table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of cognitive behavioural therapy content

| Session | Themes to be discussed | Time period related to surgery (weeks) | Duration of sessions (min) |

| 1 |

|

−2 | 60 |

| 2 |

|

4 | 45 |

| 3 |

|

6 | 45 |

| 4 |

|

8 | 45 |

| 5 |

|

10 | 45 |

| 6 |

|

12 | 45 |

| 7 |

|

14 | 45 |

All sessions have a fixed layout: each session begins with a brief introduction of the session. Next, the homework assignments from the previous session are discussed (except in the first session). Then the themes of that particular session are explained. Together, the patient and psychologist will execute assignments to support positive coping skills. Finally, the patient and psychologist will decide on one or more homework assignments that should be carried out in preparation for the next session before concluding the session by a brief evaluation. To assist the executing psychologists, each session in the CBT protocol provides examples of (homework) assignments that psychologists can complete together with patients. All sessions have a duration of 45 min, except the pre-surgical session which will take 1 hour. In addition to the sessions provided by a psychologist, an online module CBT is available containing psycho-education about general chronic pain. It furthermore has chapters on pain and behaviour, emotion, thoughts and attention. There are also assignments that participants can complete. Patients in the CBT-group can use this online module freely to re-explore information already explained in the face-to-face sessions.

Data collection, management, analysis and monitoring

Data handling, storage and archiving

All information obtained is considered to be confidential information and will not be distributed to third parties. The research data will be stored pseudo-anonymously in a database. Each subject will be given a code, consisting of letters and a number (eg, RST-ARNH-00001). The key linking this code to patient identity will be stored in a separate and secured file. Personal data will be handled in accordance with the Dutch General Data Protection Regulation. The research data will be stored for 15 years after finalisation of the project. The data required for the trial will be entered by the investigation sites into electronic Case Report Forms. Detailed edit checks will ensure high quality standard of the data entered in the database. The principal investigator of each participating study site will assure that queries are resolved by the site on an ongoing basis. In the case of missing data, a comparison with the original source data will be performed in order to locate missing data. If we are unable to retrieve missing data, this will be represented by a symbol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed, using SPSS software (V.27), after all data of each participant has been collected. The significance level has been established at 0.05. Descriptive statistics will be calculated for both groups. An interim analysis will not be performed.

To answer the primary question, whether adding CBT to usual post-surgery care significantly improves QoL, multivariate repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) will be conducted with time (baseline vs T1 and T2) as within-subjects variable, group (CBT vs usual care) as between-subjects variable and the QoL measures as dependent variables. If variability between subjects is larger than expected (eg, due to missing data, non-normal residuals or a temporarily study halt because of the COVID-19 pandemic), a linear mixed model will be used instead of repeated measures MANOVA. An intention-to-treat analysis will be followed in the case of follow-up losses. Participants that have withdrawn from treatment will receive the same follow-up as described above: they will be asked to fill in questionnaires and a hair sample will be collected at T1 and at T2.

Secondary endpoints will be analysed with computed mediation models using validated methods (using Hayes macro26). Briefly, regression models are calculated with the change in QoL as dependent variables (difference in QoL at baseline and T2), group (CBT vs usual care) as independent predictor and pain cognition, pain intensity, fatigue and stress measurements as mediators. Here, we can answer the question to what extent improvements in pain cognitions, pain intensity, fatigue and stress levels underlie the anticipated positive effect of CBT on improvement in QoL in patients undergoing endometriosis surgery.

Data monitoring

A certified on-site monitor will conduct periodic monitoring visits with adequate frequency to ensure that obligations of participating sites are being fulfilled and that the facilities continue to be acceptable. All serious adverse events will be reported to the METC after obtaining knowledge of the events. All adverse events will be followed until they have abated, or until a stable situation has been reached. A summary of the progress of the trial will be submitted to the accredited METC once a year.

Premature termination of the study

The study can be terminated prematurely if there is evidence of an unacceptable risk for trial subjects, if there is reason to conclude that it is not feasible to collect the data necessary to reach the study objectives and it is therefore not ethical to continue and in case of failure of the investigator and/or staff to follow either good clinical practice standards or to adhere to protocol requirements. The decision to end the trial prematurely will be made by the coordinating investigators in close collaboration with the principal investigator.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval

The study protocol has been approved by the METC of the region Arnhem-Nijmegen from the Radboud University Medical Centre on 2 September 2020. It has been registered on ClinicalTrails.gov on 3 June 2020. Amendments, changes made to the research protocol after a primary favourable opinion by the accredited METC has been given, will be notified to the METC that gave the primary favourable opinion. After an amendment is approved, informed consent will be obtained from participants after receiving sufficient verbal and written information about the protocol amendments, when this is required by the METC. Participants will be asked consent to use collected data in ancillary studies.

Disclosure of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data access

Project principal investigators will have direct access to their own site’s data sets, and will have access to other sites data by request. To ensure confidentiality, data dispersed to project team members will be blinded of any identifying participant information.

Ancillary and post-trial care

Patients that are enrolled in the study are covered by indemnity for negligent harm through the standard health insurance. Due to the used intervention the METC did not require the sponsor to take out additional insurance to cover non-negligent harm associated with the protocol. If patients in either the control or intervention group wish to respectively start or continue psychological treatment after the study has finished, they are instructed to contact their gynaecologist or general practitioner for referral for psychological treatment.

Public disclosure and publication policy

The findings of this study will be published in scientific journals and will be presented at scientific conferences. Authors that substantially contributed to the results of this study will be granted authorship. The research protocol, original data set and statistical code will be available on request in accordance with the conditions of ethics approval. If participants wish, they will be notified of the findings when they are available.

Discussion

Patients suffering from endometriosis often have impaired QoL and severe chronic pain. Non-medical therapies including cognitive behavioural interventions have been widely used and proven effective in suppressing pain and pain-related problems in several chronic pain syndromes.8–10 13 27 28 In this study we aim to determine the efficacy of CBT to improve QoL in patients undergoing endometriosis surgery due to endometriosis-associated chronic pain. To our knowledge, this is the first research project investigating this.

To determine whether CBT is effective in improving QoL, participants will be randomised into two groups. The control group will receive surgery and care as usual, and the intervention group will additionally receive seven sessions of CBT.

Strengths and limitations

For this study a CBT protocol was developed by members of the research team consisting of gynaecologists experienced in treating women with endometriosis and of psychologists with experience in CBT, chronic pain and/or treating patients diagnosed with endometriosis. Importantly, patients’ opinions on CBT were taken into account during development of the CBT protocol. By involving patients in the development of the CBT protocol we believe that the CBT protocol better meets the needs of this specific patient group. Using a fixed CBT protocol ensures that the intervention can be carried out congruently across all participating sites and by all executing psychologists. This minimises differences in therapy. Moreover, frequent sessions of intervision between all executing psychologists will take place in order to address possible issues and queries in the execution of the CBT protocol. This will ensure in-between centre consistency and reduce variability even further. At the same time, room for individual adjustments is facilitated in the design of the CBT protocol in order to meet specific needs of individual patients.

It is important to note that CBT will be given to patients who will undergo another treatment for endometriosis: reduction surgery. One session of CBT will be scheduled before the surgical procedure, the other six sessions will take place after surgery. Prior to surgery, patients with endometriosis-associated chronic pain have a physical explanation for the pain they experience since the endometriosis is still present at that time. After surgery, the endometriosis as cause for their pain will be removed but they may still suffer from chronic pain symptoms. At that moment, CBT may be effective in treating the psychological aspects of their chronic pain symptoms. Parrish et al29 showed in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that CBT combined with lumbar spine surgery improves QoL compared with usual care or an alternative therapy. Combining CBT with surgical treatment will stress the importance of a combined intervention targeting both physical and psychological determinants of pain as well as its interaction and will support the idea that gynaecologists, psychologists and researchers take patients’ symptoms seriously. In our opinion, this is an important strength of our study. Another strength is that we measure two indicators for stress: an assessment of self-reported stress measured by a questionnaire as well as an indicator for stress measured via cortisol extracted from hair. The scalpel hair cortisol measurement enables us to objectively quantify if CBT contributes to chronic stress present in participants.

The most important limitation of this study protocol is the difference in attention given by healthcare professionals to patients in the intervention and the control group. Because women in the intervention group will undergo seven sessions of CBT, they will get more attention from a healthcare professional as compared with women in the control group. More attention because of more contact time might lead to better QoL on itself. To compensate for this, we ideally would have added a third group of patients who would receive endometriosis-reduction surgery and seven non-therapeutic appointments with, for example, a nurse. However, this would have greatly increased the required number of participants, thereby increasing the costs of the study as well as the required time period for the inclusions. Because we aimed to compare usual care with the CBT intervention, we chose to investigate the two groups described in this protocol. It is important to stress that women in both the intervention as well as in the control group may contact their endometriosis nurse as often as they need for support or for answering questions.

Another limitation is that due to the used intervention, we are only able to blind accessors and gynaecologists performing the operation for treatment allocation. Psychologists performing the intervention and, more importantly, participants cannot be blinded which can introduce bias.

Finally, presence or absence of motivation to undergo CBT may bias the results of this study. From motivational interviewing30 it is known that motivation to undergo psychological therapy can influence treatment results. In our study, prior to randomisation we will measure patients’ motivation to undergo psychological treatment. After finishing the treatment, we will analyse whether there were in-between group differences with respect to group allocation preference and disappointment as well as motivation to undergo cognitive behavioural treatment.

Clinical implications

Depending on the outcome of our study, advice will be provided whether CBT should be added to the treatment of patients undergoing endometriosis reduction surgery. If this study shows a positive result, patients may have an additional treatment options to improve the quality of their daily lives. Results of this study could moreover pave the road to fund more clinical trials, cost-effectiveness and implementation studies on the use of CBT in patients diagnosed with endometriosis specifically and chronic pain conditions in general.

Administrative information

Trial acronym

COGENS

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04448366. Registered on 3 June 2020.

Current protocol version

8 (1-6-2021)

Trial sponsor

Rijnstate Hospital

Address: Wagnerlaan 55, 6815 AD, Arnhem, The Netherlands

Telephone: +31 088 005 8888

Website: www.rijnstate.nl

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AN conceived the study. CMV, DB, JO and AN initiated the study design and ZB helped with implementation. CMV and AN are grant holders. JO provided statistical expertise in the clinical trial design. AIdS, EGH, HSMJD and CL helped develop the CBT protocol. All authors contributed to refinement of the study protocol, revised different versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Radboudumc-Rijnstate PhD funding, grant number W.000003.1.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004;364:1789–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vercellini P, Crosignani PG, Abbiati A, et al. The effect of surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: the other side of the story. Hum Reprod Update 2009;15:177–88. 10.1093/humupd/dmn062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Aken M, Oosterman J, van Rijn T. The effect of endometriosis surgery on biopsychosocial correlates of pain 2019.

- 4.van Aken MAW, Oosterman JM, van Rijn CM, et al. Pain cognition versus pain intensity in patients with endometriosis: toward personalized treatment. Fertil Steril 2017;108:679–86. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olatunji BO, Hollon SD. Preface: the current status of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010;33:xiii–xix. 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark DA, Beck AT. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. In: Foreyt JP, Rathjen DP, eds. Cognitive behavior therapy: research and application. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1978: 109–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark DA. Cognitive restructuring. The Wiley Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy, 2013: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134192. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-Behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;69:153–66. 10.1037/a0035747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Chang Y, Kennedy SA, et al. Perioperative psychotherapy for persistent post-surgical pain and physical impairment: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:1304–14. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boersen Z, de Kok L, van der Zanden M, et al. Patients' perspective on cognitive behavioural therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: a qualitative study. Reprod Biomed Online 2021;42:819–25. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archer KR, Devin CJ, Vanston SW, et al. Cognitive-Behavioral-Based physical therapy for patients with chronic pain undergoing lumbar spine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain 2016;17:76–89. 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karekla M, Constantinou P, Ioannou M, et al. The phenomenon of treatment dropout, reasons and Moderators in acceptance and commitment therapy and other active treatments: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Eur 2019;1:1–36. 10.32872/cpe.v1i3.33058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez E, Salem D, Swift JK, et al. Meta-Analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: magnitude, timing, and moderators. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015;83:1108–22. 10.1037/ccp0000044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World health Organization . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD), 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/classifications/classification-of-diseases

- 17.Hart VA. Infertility and the role of psychotherapy. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2002;23:31–41. 10.1080/01612840252825464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chachamovich JR, Chachamovich E, Ezer H, et al. Investigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: a systematic review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2010;31:101–10. 10.3109/0167482X.2010.481337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, et al. Quality-Of-Life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1171–8. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association AP . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5: Amer psychiatric PUB incorporated 2013.

- 21.van de Burgt TJM, Hendriks JCM, Kluivers KB. Quality of life in endometriosis: evaluation of the Dutch-version endometriosis health Profile-30 (EHP-30). Fertil Steril 2011;95:1863–5. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones G, Jenkinson C, Kennedy S. Evaluating the responsiveness of the endometriosis health profile questionnaire: the EHP-30. Qual Life Res 2004;13:705–13. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021316.79349.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Zee K, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand Met de RAND-36. Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken, reeks meetinstrumenten 1993;3:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004;130:601–30. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Aken M, Oosterman J, van Rijn T, et al. Hair cortisol and the relationship with chronic pain and quality of life in endometriosis patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018;89:216–22. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, 2013: xvii, 507-xvii, p. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans S, Fernandez S, Olive L, et al. Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2019;124:109756. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Till SR, Wahl HN, As-Sanie S. The role of nonpharmacologic therapies in management of chronic pelvic pain: what to do when surgery fails. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2017;29:231–9. 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrish JM, Jenkins NW, Parrish MS, et al. The influence of cognitive behavioral therapy on lumbar spine surgery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2021;30:1365–79. 10.1007/s00586-021-06747-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. Guilford press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.