Abstract

Objectives:

This study aims to explore the psychosocial issues faced by the primary caregivers of advanced head and neck cancer patients with the primary objective to understand their experiences within social context.

Materials and Methods:

Burden and QOL of caregivers (n = 15) were quantified using Zarit Burden Interview schedule and caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC), respectively. Primary caregivers (n = 10) were interviewed using semi-structured interview schedule. Thematic analysis was employed to analyse the qualitative data. Descriptive statistics was used for quantitative data.

Results:

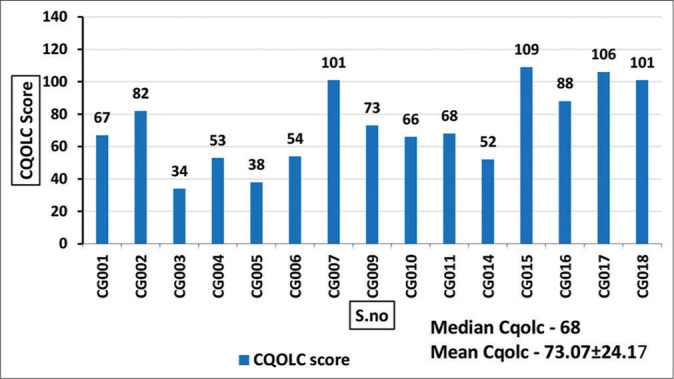

Four major themes emerged: (1) Impacts of caregiving, (2) coping with caregiving, (3) caregiver’s appraisal of caregiving and (4) caregiver’s perception of illness. Majority (73.3%) of the caregivers had QOL below 100. The mean CQOLC score was 73.07 (SD 24.17) and most (46.7%) of the caregivers reported mild-to-moderate burden, while 27% had little to no burden. The mean ZBI score was 32.4 (SD 18.20).

Conclusion:

Caregiving impacts the physical, emotional, financial and social aspects of caregiver’s life. Caregivers adopt active coping strategies to overcome the impacts of caregiving. Family acts as a major source of strength to manage the emotional constraints faced by Indian caregivers. Cultural beliefs and values of caregivers influence their appraisal of caregiving situation. Majority of the caregivers experienced mild-to-moderate burden while most of the caregivers scored low on QOL.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, Head and neck cancer, Quality of life, Thematic analysis

INTRODUCTION

India has one-third of oral cancer cases in the world.[1] About 80% of them have advanced disease at presentation[2] with little scope for curative treatment and most are, therefore, left with the only option of supportive care. Palliative care penetration in India is only about 1–2%.[3,4] The limited availability of palliative care shifts the paradigm of palliative care services from formal health-care professionals to the family members who are forced to don the role of caregivers.

A primary caregiver is the one who provides unpaid care at home and who has a pre-existing relationship (relative or friend) with the person for whom care is being provided. Primary caregivers are usually spouses, partners or adult children, who usually live with the cancer patient in the same premises. This informal home-based care poses many complex issues and challenges that affect the caregivers.[5] It is of primary importance to examine those who bear much of the responsibility in caring for the cancer patient.[6] It has been shown that caring for those at the end of their lives at home weighs heavily and impacts the well-being of family caregivers.[7] Informal caregiving is associated with impaired physical well-being, emotional disruptions, uncertainty about the future, lifestyle interruptions, work-related changes and increased financial strain.[8,9] The multifaceted distress experienced by the caregivers is conceptualised as caregiver burden or stress.[10,11] Various factors such as age, gender, marital status, relationship and employment were found to be mediators of caregiver burden.[12-14]

Palliative care is all about improving the QOL of not only patients but also their families. Since there are limited studies regarding caregivers of palliative care patients in our country, we decided to explore the psychosocial issues of caregivers with advanced cancer. Working in outpatient palliative care and seeing the struggle of the caregivers, especially in head-and-neck cancer, made us explore the psychosocial issues of caregivers of advanced head-and-neck cancer patients. The primary objective is to understand the caregiver’s experiences within the social context. Using a mixed method study, we aimed to:

To quantify the caregiver burden using Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) schedule and quality of life in caregivers using caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC) scale

To qualitatively explore psychosocial issues faced by the caregivers of palliative care patients with advanced head-and-neck cancer.

Setting and participants

This research was carried out as part of the thesis for the Cardiff MSc (Palliative medicine) course and proceeded with approval from the institutional thesis review committee, between January 2016 and May 2016. Through purposive sampling, primary caregivers accompanying advanced head-and-neck cancer patients attending the palliative care outpatient clinic were included in the study. Recruitment of participants was done after they understood a detailed printed format stating the study purpose and obtaining the signed informed consent for participation. The confidentiality of the participants was ensured throughout.

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were included in the study:

Age above 18 years

Should be the primary caregiver of advanced head-and-neck cancer patients

Those who speak and understand the regional language (Tamil) well.

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded from the study:

Caregivers with known psychiatric illness or those on treatment for psychiatric illness

Those who provide paid services.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Both descriptive survey approach and a qualitative phenomenological approach were adopted for this study.

The quantitative data collection preceded the qualitative in-depth interview. A sociodemographic sheet was used to collect the personal details of the caregivers and the patient details such as diagnosis, duration of illness and treatment history. Caregiver burden was assessed using the ZBI and quality of life was assessed using the CQOLC.

-

Quantitative: Quantitative data were collected using standard validated tools –

- ZBI schedule,[15] a self-reporting validated tool with translation available in the regional language (Tamil) was used to quantify the burden. This multidimensional tool was used to measure strain experienced by caregivers in four domains – social, physical, financial and emotional domains. Each question is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, quite frequently = 3 or nearly always = 4) where the caregivers are to indicate as to how often they have felt from ‘never’ to ‘nearly always.’ The scores are summated and interpreted as follows: 0–21: Little or no burden, 21–40: Mild-to-moderate burden, 41–60: Moderate-to-severe burden and 61–88: Severe burden

- CQOLC is a self-reporting instrument to assess the quality of life of cancer carers developed by Weitzner et al.[16] with adequate validity (0.95) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91). This is a 35-item self-administered questionnaire with each item having a score from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The maximum score is 140, the higher the score better the QOL. There are subscales for burden, disruptiveness, positive adaptation and financial scales. These four factors include 27 items, with eight additional items not loading on to these factors.

Qualitative: Qualitative research was conducted fulfilling the COREQ criteria.[17] Face-to-face interview of caregivers using a semi-structured questionnaire was carried out by a psycho-oncologist with experience. We chose a third person for the interviewing to avoid respondent bias as the researcher was also the treating palliative care physician. A trial interview preceded the formal interviews and helped structure the open-ended questions. The questions of the semi-structured interview in this study were mainly targeted to explore the psychosocial impact of caregiving on caregiver’s four main life domains: Physical, emotional, social and financial and to know whether the patient or the caregiver could find any meaning in their role of caregiving. The open-ended questions are given in [Table 1]. Besides, the interviewer was permitted to allow the conversation to stray away from the topic at her discretion as appropriate to maintain the flow help in capturing the responses. The interview was in the vernacular (Tamil) and audio recorded. The duration of each interview ranged from 30 min to 45 min. All the recorded data were appropriately labelled and handed over to the researcher for transcription, translation and analysis. The quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and expressed as percentage, mean and standard deviation. Qualitative data analysis was done using thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke in 2006.[18] Accordingly, all six steps were followed – familiarisation of data, generating the initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report. The extraction of themes, subthemes and the categories describing the phenomena were done manually using colour coding and derived according to their broader meaning of significance, thereby making it possible to interpret the essence of the entire qualitative data of this study in a schematic manner.

Table 1:

Semi-structured interview questions.

| S. No. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | Could you elaborate on your experiences with caring for your relative? |

| 2. | Can you describe the ways in which you take care of your relative? |

| 3. | How your role as a caregiver affects you – physically, psychologically, socially and financially? |

| 4. | Could you share how you manage the problems you experience as a consequence of caring for your relative? |

| 5. | What is your understanding about the present illness of your relative? |

| 6. | How do you think your caregiving benefits the care recipient? |

RESULTS

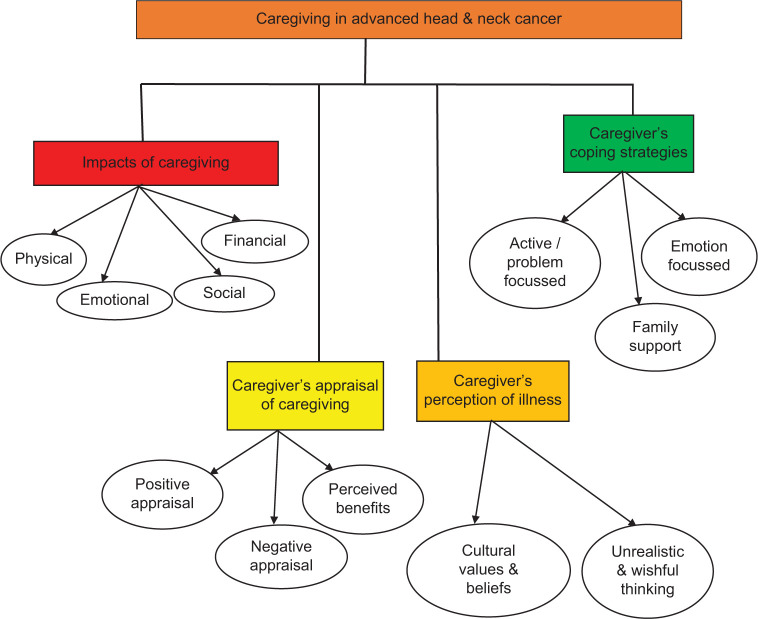

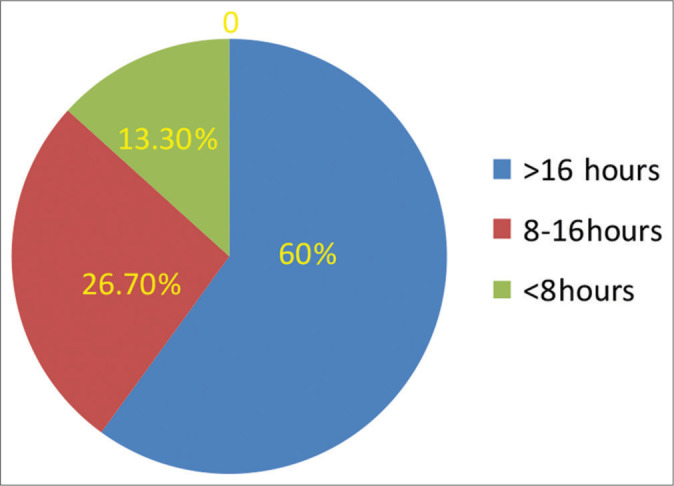

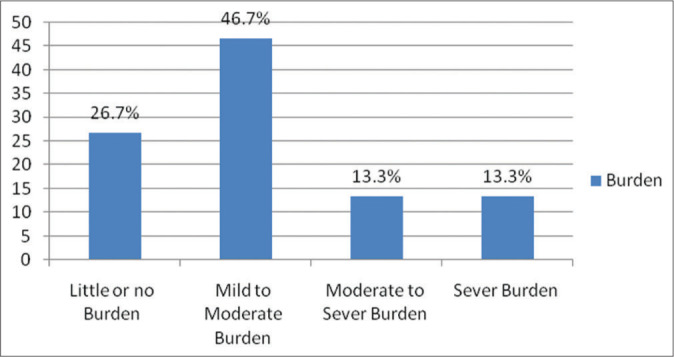

We recruited 18 caregivers but three were excluded due to incomplete data. We had 15 caregivers for quantitative analysis but used only 10 for qualitative as we had difficulty in retrieving the exact information from the voice recorder in the remaining five. The demographic details are given in [Table 2]. The duration of caregiving is displayed in [Figure 1]. ZBI scoring revealed that 46.7% of the caregivers experienced mild-to-moderate burden. The mean ZBI score was 32.4 ± 18.2. The mean CQOLC score was 73.07 ± 24.17 and the median CQOLC was 68 (range 34–109) [Figure 2 ]and [Figure 3].

Table 2:

Demographic data.

| Characteristics | Caregiver (%) n=15 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 4/11 |

| Age range | 19–65 (mean 46.1) |

| Spouses/parents/children | 11/2/2 |

| Married/widowed/single | 11/2/2 |

| Literate/employed | 13/11 |

| Monthly household income <5000 INR | 12(80%) |

| Financial help from family | 8 (53%) |

| Substance abuse | 1 |

| Oral/pharynx/larynx/parotid cancers | 9/4/1/1 |

| Patients who were primary wage earners | 11 (73.3%) |

| Duration of illness (range) | 3–24 months |

| ZBIa(mean) | 32.4±18.2 |

| CQOLCb-median (range) | 68 (34–109) |

Zarit Burden Interview score, bcaregiver quality of life index-cancer

Figure 1:

Duration of caregiving.

Figure 2:

Zarit Burden score of informal caregivers.

Figure 3:

Caregiver quality of life index-cancer scoring of caregivers.

Four major themes with several subthemes emerged on analysing the qualitative data, as depicted in [Figure 4].

Figure 4:

Thematic derivation of psychosocial issues in advanced head-and-neck cancer caregivers.

The major themes include:

Impacts of caregiving

Coping with caregiving

Caregiver’s appraisal of caregiving

Caregiver’s perception of illness.

Impacts of caregiving

The four major areas found to be negatively impacted as a result of caregiving are – physical, emotional/psychological, financial and social.

Physical impacts of caregiving

Caregivers were unable to focus on their physical health including their sleep, appetite and overall health, as a result of caring for the patient (n = 5 [50%]).

Sleep

Sleep, a predominant aspect that influences physical well-being, was found to be affected as a result of caregiving. Alteration in the pattern and quality of sleep was reported due to the direct effect of caregiving or as a result of their distress regarding the illness of their loved one. Caregivers reported their sleep as being intermittent as a result of addressing the needs of the patients during nighttime.

[I am not able to sleep adequately in the night as I keep waking up to look after him, my sleep is affected] – (CG003)

[I am not able to sleep properly. I don’t get sleep till 12.00 at the midnight. After having dinner, will sleep for some time but later thinking about my wife I lose some sleep]. – (CG009)

In contrast, some caregivers stated that their sleep was not affected and that the quality of their sleep was good. They attribute their uninterrupted sleep pattern to the long tiring day and work stress during daytime.

[No, she doesn’t wake me up, I sleep well wake up sharp by 6 am, and will go about my work] - (CG017)

[No. I do not lose sleep. I work a lot from morning to evening. Even if I sleep for a short duration, I sleep well.] (CG001)

Appetite and eating habits

Appetite is another major element of physical health that was found to be compromised among majority of the caregivers the reasons were both skipping their meal due to their busy schedule, and lack of interest in eating as a result of distress caused by the advanced disease of their loved one.

[Then I don’t cook anything separately for myself, whatever food I prepare for him, I eat a small portion of it. I don’t make anything special for myself] – (CG003)

[I have to care for him, I don’t sleep enough, not eating adequately]- (CG010)

Health impacts

With the sleep and appetite being affected, caregivers perceive deterioration in their overall health because of the physical exertion as a result of caregiving.

[Now my health is affected because I take care of him day and night] – (CG003)

Emotional or psychological impacts

While physical health is one component of quality of life, psychological health also contributes significantly. Caregivers experience major psychological distress seeing their loved one suffering from the progression of the disease and worsening of the symptoms (n = 5 [50%]).

[It is very distressing. It distresses me that he is suffering so much. I am not able to see him suffer. I am not able to bear it] – (CG001)

[Whenever he complains of ‘pain,’ I give him tablets. But when he gets pain again within a short time, I feel miserable, more of psychological distress].- (CG010)

[I feel psychologically distressed by thinking about his condition and as the doctors have also told that he cannot be cured] – (CG011)

The reason for psychological distress not only pertains to the disease condition of the patient but also the interpersonal relationship between the patient and the caregiver. Caregivers reported that the poor relationship resulted in increased psychological distress. Caregivers also reported that they experience negative emotions and they attribute it to the frustration caused by the hectic schedule.

[When he gets angry, I just think why he is doing like this. Even I get somewhat angry. Suddenly he raises his voice I used to think why he is shouting like this and I get irritated at that time only otherwise there is nothing much].- (CG006)

[I don’t have any trouble in specific but I have hatred towards my life generally and have lost hope now and been thinking of my life to end soon].- (CG016)

Guilt, as a manifestation of their decision about the place of care, was reported by a caregiver.

[What I think is…. Everyone asked me why I had brought him to this hospital, I had money, and that I could have taken him elsewhere. What I thought was, somebody had told me this hospital is good. If I take him elsewhere, I wouldn’t be able to save him. A person working in my office had got the same disease and in the same stage. He is doing well now, but my husband is in this condition. He was doing very well before. He used to look very… handsome. This has happened. I feel sad when I think about this]. - (CG001)

Uncertainty and fear regarding the future and the health of the patient were also reasons for their distress.

[Ahh. I feel tensed that this is happening. I feel fear that something will happen to him and I would not be able to do anything]. - (CG001)

Financial impacts

Change in work schedules and inability to go to work as a result of the hospitalisation or the poor physical condition of the patient has had a significant economic impact on the life of the caregiver (n = 3 [30%])

[He is unable to go for his job due to his present condition, I am also unable to leave him and go for a job. So, we are suffering financially too]. (CG010)

[He cannot go for any job, but I have to look after my family with the income from the shop. I find it very difficult for me]. (CG011)

The financial burden is overwhelming in those who are already in a lower economic status.

[I don’t have anyone to help me. No one gives me money. Adding to that I am not economically sound and all my people are also not having money like me. They are also like me in the first place. How can they provide me any help? nobody can help each other]. - (CG014)

Caregivers report reduced distress when the burden of the hospital expenditures is being taken care of.

[If there is hospital expenditure, I would find it difficult, but as it is free of cost, I have to bear only the transportation charges. I have food expenses only. What are we going to cook? Eat? So, expenditure is only minimal, I can eat and manage it with my income]. -(CG009)

Social impact

Carers who have had an active social life perceived that caregiving has limited their social life, as they are occupied with their responsibilities of taking care of their loved one and hence they do not find time or interest to engage in the social activities (n = 2 [20%]).

[I am not able to go anywhere out, not even to temple. Then I have stopped visiting my relatives, not in communication with them, all these issues affect me] (CG003)

[This 1 year, taking care of him itself takes a lot of time. I am not able to do anything much]. -(CG014)

Coping with the role of caregiving

The second major theme that emerged from the analysis was the process of coping with issues that arose during caregiving. Perceived family or social support was one major determinant of psychological distress. Caregivers who have received financial and emotional support from family were found to be coping well with the task of caregiving.

Perceived supports

Financial support

Caregivers perceived that financial support received either from their relatives or friends has reduced their distress to a larger extent.

[She (mother) gets a pension. She gives a part of it to me so that her daughter (i.e. caregiver) gets to lead a good life. She tells me to save him somehow. She is the one who helps me a lot. I get money for treating my husband only from that] (CG001)

[Yes, I have a little bit of financial difficulty but his elder brother and my parents support it]. (CG006)

Whenever the expenses are within their means, carers can manage even with little support from their close family.

[I manage the financial issues through my work. I don’t have many expenses. When my children visit us they give Rs.100/- and I can manage with that.] (CG009).

Emotional support

The emotional support received irrespective of any sources be it parents, children, workplace or neighbours was found to be a major stress reducing factor and it helped the caregivers in dealing with the overwhelming psychological burden.

[I would talk to my son for some time. Sometimes, I speak to my neighbours when they give me emotional support, I feel better. I talk to my mother over the phone who provides me support] -(CG001).

[If I have any kind of fear in my mind, I call my mother. She supports me at that time, saying that I am doing everything I can, and if he is not getting cured, I cannot do anything. She gives me full support] (CG001).

Active coping strategies

Caregivers also reported various active problem-focused or emotion-focused coping strategies that help them deal with the situation effectively.

[I am not able to take care of him, still, I have to take care of him, so I am doing it. What to do about it]. (CG014)

[Whatever difficulties come to us; we will have to face it by ourselves. It’s no use in telling it to others. It’s in no way useful by telling to you and others. How much ever big problems come our way I just have to put in my heart and think about it on my own.] (CG014)

[We have to manage. What else can be done? I do not go to college or anywhere out. I am with my mother full time. That is also my wish. We take care of everything.]- (CG018)

Carers accept their role without any negative emotion despite the difficulties they encounter, intending to protect their loved ones from any psychological distress and guilt feelings.

[Hmm… Yes, I do have. Every morning after waking up I keep thinking about where to go? I have to go for my job as well as I need to bring her to hospital, once in ten days, have to go here and there. I struggle; still, I cannot go and express this to her right.](CG009)

[About that. I do not get any rest when I attend to him. I cannot tell him that because he would start blaming himself]. – (CG001)

Religious and spiritual ways of coping were also adopted by the caregivers in their overwhelming situation:

[Nobody can solve these problems, only we should solve them. There is no point in telling anybody, hence I accept it and have left everything in God’s hands and moving on]. -(CG017)

[Whatever is destined to happen will happen. Nothing will wait for us. I carry on thinking all these to be God’s wish]– (CG017).

Dependent children in families aided in the process of coping with the caregivers in finding meaning and purpose in life.

[I go for work and I don’t like depending on others. The only thing I have in my mind is I have to raise my kids by myself till am physically fit. I have two daughters so have to take up the responsibility for that]. -(CG016)

In contrast, caregivers who used avoidance strategies to cope seem to be negatively affected and suffer.

[I am somehow struggling and managing it. He does not think about it. That’s why even I stopped thinking about him and I don’t take into my mind whatever he tells. I just leave it to god and I have suffered a lot madam] –(CG016)

Caregiver’s appraisal of caregiving

Positive appraisal

Caregivers appraise the situation positively and consider it only natural for them to take on the role of caregiving. Appraising the situation positively reduced the psychological distress and the feeling of being burdened.

[Since my wife is not doing well so if only, I have to do this as a husband to her, I dare not? Only we have to look after each other. This is how we have lived our lives. Now, we are about 50 years old. At this age this disease has affected her, so what can we do about that? Only I have to take care]. -(CG009)

[I am interested in taking care of her till death and I don’t get irritated at all. It is an unavoidable situation right, She does not have her parents too to take care so in this situation only I should take good care of her right] -(CG017).

Perceived benefits of caregiving

Carers, who perceive that the care they are providing is of help to their loved ones and that it is protecting them from the adverse psychological outcomes, felt relieved and content.

[Yes, it supports her emotionally and psychologically when I take care of her. If I am not taking care, then she tends to develop frustration. Her happiness and satisfaction depend on how much I care for her. I take good care of her. If I don’t care for her, then she will get frustrated and may aggravate her illness, So I take care of her to my best] – (CG009)

[If I am not taking care, then she would feel miserable. She feels that no one is taking care of her and also might feel sorry. If her parents had been there then they would have taken good care of her. She may feel sad. So, now there are no such feelings.] (CG009)

[He is happy that I am taking care of him well now]. -(CG014)

Carers who take care of patients with physical limitations feel satisfied with their role especially in the absence of family support and even take pride in that they are the only pillar of support on whom their loved ones rely.

[Yes, even if anyone else is there also, she will tell only me about her pain] -(CG017)

[Yes. As I am always there beside him to give care. Whenever he has pain, I give him pills, feed him, look after him and do everything for him. That is why he is feeling good]. -(CG010)

One caregiver stated that she was satisfied in her role as a caregiver as she can fulfil the financial needs of the family by being employed, as her husband is affected by the illness. Caregivers change their outlook at caregiving by assuming new dimensions in their existing relationship with affected loved ones.

[There is nothing of that sort; we generally take care of our children, right? Likewise, I take care of my son like a 3-month-old baby]. -(CG003)

[I take care after I come from work. I bathe her, I cook for her and I feed her, and give her juice. I do all the work. I wash her clothes and do all the household work and look after her like a doll]. -(CG009)

Poor interpersonal relationship between the patient and the caregiver results in failure to see any kind of benefit or satisfaction out of their roles among the caregivers.

[There is no gain in taking care of him. I don’t get a benefit or a good name for that. He doesn’t think about me. He doesn’t have thought of me. I struggle a lot and he doesn’t give much importance to that. Even yesterday he was scolding me like am not taking care of him and I didn’t bring any money from my family and taking care of him in his mother’s money and something like that ]. -(CG016)

Caregiver’s perception of illness

The final theme that emerged is the perception of the illness from the caregivers’ point of view. Perception of a terminal illness may be influenced due to various factors such as culture, values and beliefs of an individual. The negative perception of the illness indicates a negative attitude toward caregiving and more perceived burden. Going through the qualitative data, three subthemes emerged which had influenced their perception regarding their loved one’s illness.

Values and beliefs

The caregivers believe that they have to be dutiful and take responsibility for the present situation, as they perceive the illness to be a punishment for their past sinful acts.

[I don’t know what sin I have done before. It is the karma that has affected my son now. To rectify that karma I have to undergo and have to save my child by caring for him ] -(CG003)

Caregivers also perceive the illness to be a devastating one that disrupts their existing family structure which leads to poor psychological well-being which, in turn, impacts their quality of life.

[He has become like this. How happy we were. He has got this disease. No one should get it.’ That is what I think. (CG crying) Family. No one should get this disease. That is what I think. I feel very distressed. My family has lost its happiness. No one should face such difficulty. That is what I think ]. -(CG001)

Wishful thinking

Caregivers reported their wishes which seem to be influenced by interpersonal attachment and cultural beliefs.

[I wish that only my son should do my cremation, especially I shouldn’t do his last rites. Let him do it for me first, then I don’t bother what happens to him later. Hence, I pray to God that my child should do the last rites for me ]. - (CG003)

Unrealistic expectations

Despite their knowledge about the prognosis of the disease, carers had certain unrealistic expectations about the course of illness.

[All I want is my son to get well and be ambulant, socialise with others just like how he used to before I also want him to earn and feed me at least once (cries.)] -(CG003)

[Hoping that she would get better]. -(CG018)

[We will be happy if he is cured. We pray to God for the same.] (CG006).

DISCUSSION

The demographics of caregivers of head-and-neck cancer patients in our study were female spouses, with low literacy levels, while many of them were employed, their income levels were low. Almost all of these factors have been shown to predict increased levels of caregiver burden and a lower QOL in earlier studies.[19-24]

Majority of the caregivers in this study had mild-to-moderate burden (46.7%) and a significant number experienced moderate-to-severe burden (26.6%). This increased level of burden could be attributable to the shift in roles, loss of a job and meeting the physical and psychological needs of the patient as can be made out from our qualitative interview. A study by Lukhmana et al. from Delhi reported that the majority of their caregivers (56.5%) had little or no burden.[25] This contradiction in the two studies from the same country (India) using the same tool (ZBI) in their regional languages (Tamil and Hindi) could be attributed to the fact that all the patients in the present study were in their palliative phase while the cohort from Delhi was receiving active treatment and can also be due to difference in the sample size.

The median CQOLC score of our caregivers was 68. The low mean (73.07 [SD 24.17]) and median CQOLC score signify the overall reduction of QOL mostly due to physical impact, emotional distress and the financial hardships faced by the study sample. Another study from Delhi using CQOLC stated that caregivers with lower socioeconomic status in developing countries are at risk of lower QOL.[26] Likewise, Nayak et al. in their study also found that caregivers of advanced cancer patients attributed financial burden to negatively influence their QOL,[27] being a charitable cancer hospital, all our patients too were from lower socioeconomic group.

The findings of our qualitative interview have revealed that without formal health care and financial support systems informal caregivers are forced to bear the brunt of caregiving responsibilities. The major impact was on all the four domains – physical, emotional, financial and social influenced by the symptom burden and personal care needs of the care recipients. Similarly Brazil et al.[28] in their qualitative study reported that care recipient symptoms and personal care needs were the primary stressors in the Canadian caregivers. Further they reported that the informal support received from their family, friends and neighbors to be moderators of caregiving stress.

Out of the four domains that emerged from qualitative analysis, two of them had financial factors affecting them both positively as perceived support for coping and a negative impact of caregiving when the loss of earning resulted in financial loss.

Despite the negative impacts of caregiving caregivers coped up with their situation using family support, active problem focussed coping strategies, positive appraisal of the situation by finding meaning and purpose in their caregiving in addition to filial responsibility.

In our study, caregivers employed both problems focussed and emotional focussed coping methods to overcome the stress of caregiving. The findings of our study support another study from Karnataka[29] which showed that caregivers used both positive and negative coping strategies. They also found a significant negative correlation (r = −0.722, P = 0.005) between stress and coping among caregivers of palliative care patients. Papastavrou et al.[30] in their study have concluded that informal caregivers adopting emotion focussed coping to be depressed and manifest increased burden.

The perceived benefits by caregivers in our study were taking pride in being a pillar of support to their loved ones and finding meaning and purpose in their tasks. This phenomenon of self-transcendence in finding meaning and faith in their tasks help overcome adversity by caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients as observed by Enyert and Burman.[31]

Unrealistic expectations and wishful thinking were seen in our caregivers. This is not uncommon in Indian caregivers with strong interpersonal relationships and a culture influenced by filial responsibility. A recent study examining hope and its relationship to QOL found that positive readiness and expectancy as well as interconnectedness to be negatively correlated with quality of life in cancer caregivers.[32]

There are few limitations to this present study. Being a cross-sectional study, the experiences of the caregivers throughout the illness trajectory of the patient were not obtained. Given the small sample size, the quantitative data could not be further analysed, thus making the generalisability of the data difficult. However, further research with a longitudinal study will improve our knowledge of caregiver experiences throughout the illness trajectory. Knowledge gained from the study can also be used for intervention such as respite care, social and financial help to caregivers to improve their coping and decrease their burden.

CONCLUSION

Caregivers of advanced head-and-neck cancer patients in our study had their QOL impacted by the caregiving in physical, emotional, sociocultural and financial aspects. While the perception of illness bordered on unrealistic expectation and wishful thinking, most caregivers’ appraisal of caregiving was positive and they perceived some benefits in their deeds. They were able to cope with the perceived family supports and by adopting active coping strategies.

Acknowledgement

Ms. Deepika for conducting the in-depth interview.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Ramasamy T, Veeraiah S, Balakrishnan K. Psychosocial issues among primary caregivers of patients with advanced head and neck cancer - A mixed-method study. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27:503-12.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coelho KR. Challenges of the oral cancer burden in India. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:701932. doi: 10.1155/2012/701932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takiar R, Nadayil D, Nandakumar A. Projections of the number of cancer cases in India (2010-2020) by cancer groups. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1045–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajagopal MR. In: Cancer Control 2015: Cancer Care in Emerging Health Systems. Magrath I, editor. Brussels: INCTR; 2015. The current status of palliative care in India. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kar SS, Subitha L, Iswarya S. Palliative care in India: Situation assessment and future scope. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52:99–101. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.175578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakas T, Lewis RR, Parsons JE. Caregiving tasks among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:847–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:213–31. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grov EK, Fossa SD, Sorebo O, Dahl AA. Primary caregivers of cancer patients in the palliative phase: A path analysis of variables influencing their burden. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2429–39. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratnakar S, Banupriya C, Doureradjou P, Vivekanandam S, Srivastava MK, Koner BC. Evaluation of anxiety, depression and urinary protein excretion among the family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Biol Psychol. 2008;79:234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1013–25. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou Ru K. Caregiver burden a concept Analysis. J Paediatr Nurs. 2000;15:398–407. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaugler JE, Given WC, Linder J, Kataria R, Tucker G, Regine WF. Work, gender, and stress in family cancer caregiving. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:347–57. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin JM, Martin M, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: A hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20:44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge L, Mordiffi SZ. Factors associated with higher caregiver burden among family caregivers of elderly cancer patients: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:471–8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–55. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, Jr, Friedland J, Cox C. The caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC) scale: Development and validation of an instrument to measure the quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:55–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1026407010614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrank B, Ebert-Vogel A, Amering M, Masel EK, Neubauer M, Watzke H, et al. Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2016;25:808–14. doi: 10.1002/pon.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govina O, Kotronoulas G, Mystakidou K, Katsaragakis S, Vlachou E, Patiraki E. Effects of patient and personal demographic, clinical and psychosocial characteristics on the burden of family members caring for patients with advanced cancer in Greece. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, Sherwood P, Gift A, Devoss D, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:1104–18. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagedoorn M, Buunk B, Kuijer R, Wobbes T, Sanderman R. Couples dealing with cancer: Role and gender differences regarding psychological distress and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2000;9:232–42. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<232::AID-PON458>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li QP, Mak YW, Loke AY. Spouses' experience of caregiving for cancer patients: A literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60:178–87. doi: 10.1111/inr.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Given CW, Lu X, Given BA, Hricik A, et al. Predictors of employment and lost hours from work in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2008;17:598–605. doi: 10.1002/pon.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukhmana S, Bhasin SK, Chhabra P, Bhatia MS. Family caregivers' burden: A hospital-based study in 2010 among cancer patients from Delhi. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52:146–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.175584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vashistha V, Poulose R, Choudhari C, Kaur S, Mohan A. Quality of life among caregivers of lower-income cancer patients: A single-institutional experience in india and comprehensive literature review. Asian Pac J Cancer Care. 2019;4:87–93. doi: 10.31557/apjcc.2019.4.3.87-93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nayak MG, George A, Vidyasagar MS, Kamath A. Quality of life of family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2014;3:70–5. doi: 10.9790/1959-03217075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Rodriguez C. The stress process in palliative cancer care: A qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2009;27:111–6. doi: 10.1177/1049909109350176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antony L, George LS, Jose TT. Stress, coping and lived experiences among caregivers of cancer patients on palliative care: A mixed-method research. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:313–9. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_178_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H. How do informal caregivers of patients with cancer cope: A descriptive study of the coping strategies employed. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:258–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enyert G, Burman ME. A qualitative study of self-transcendence in caregivers of terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1999;16:455–62. doi: 10.1177/104990919901600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sunkarapalli G, Agarwal A, Agarwal S. Hope and quality of life in caregivers of cancer patients. Int J Indian Psychol. 2016;4:20160401. [Google Scholar]