Abstract

Objectives:

The present study aims to determine the attitudes of care providers including obstetricians, paediatricians and midwives working in perinatal, obstetric and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) wards of the selected teaching hospitals in Tehran in 2019. In addition, the challenges of providing palliative care from the perspective of these individuals have been examined.

Materials and Methods:

In this descriptive study, the research population was selected through convenience sampling based on the inclusion criteria. To assess care providers’ attitude toward the perinatal palliative care and the challenges of its implementation, in addition to the questionnaire of demographic characteristics, a researcher-made questionnaire was also used.

Results:

Most of the care providers (90.5%) believed that parents should be involved in decision-making to select the treatment type. Most of the care providers (90%) believed that the lack of prepared infrastructures is one of the major challenges in providing these types of care.

Conclusion:

Care providers have almost positive attitudes toward the various dimensions of providing perinatal palliative care, but it has not been properly implemented yet due to the insufficient knowledge of this type of care, the lack of required infrastructures (appropriate conditions in NICUs to provide this type of care, the sufficient number of staff and experts in this field), as well as the health authorities’ neglecting this type of care.

Keywords: Perinatal care, Palliative care, Hospice care, Attitude, Nurse

INTRODUCTION

Perinatal period is referred to a stage of life which is initiated from the 22nd week of gestation and continues until 7 days after birth.[1] This stage of foetal life is critical due to the numerous physiologic changes needed to adapt to extrauterine life and is associated with high mortality rates.[2,3]

Normally, about 3% of all births are accompanied with life-threatening foetal anomalies which are the main reason of mortality in the perinatal period. According to global reports, the mortality rate in perinatal period is about 8 million deaths annually, 98% of which occur in developing and non-developed countries. The rate of perinatal mortality in Iran has been reported to be 15.29 births per 1000 live births.[2,4]

Nowadays, thanks to advancements in technology and diagnostic and screening methods, the early diagnosis of congenital anomalies and foetal defects in the first trimester of pregnancy is possible, and families can be informed of such problems through pre-birth genetic testing and laboratory assessments. As a result, early diagnosis of these anomalies leads to identifying the foetus, and subsequently, the neonate is in critical conditions and, in case of survival, will need to be hospitalised in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).[5-7] In many cases, there is no definite treatment for a foetus or a neonate with wide anomalies, and just symptomatic treatments, pain control and symptom management can be applied.[7-10]

In such situations, telling the truth to parents that the foetus or the neonate will die in foetal period or a short time after birth leads to their showing reactions expressing fear, anxiety, sadness, grief, hopelessness, anger, the feeling of guilt and depression.[5,9,11,12]

Facing such a situation, a group of them might consider terminating the pregnancy, and consult about it with care providers, which is not regarded as an appropriate choice and is not recommended due to cultural, mental, religious, and, legal, social, reasons. Since the majority of Iranians are Muslims, according to the teachings of Islam, they believe that abortion is unlawful. It is also considered an illegal practice based on the laws of society.[2,13]

Besides, being aware of the foetus status, some parents, especially mothers, would like to continue pregnancy until labour, and ask the care providers for guidance in this regard.[14] On the other hand, some parents may feel frightened due to the uncertainty in pregnancy and its outcomes.[15] Despite the various tendencies of families while facing such conditions, care providers are prepared to offer a wide range of services and care to the foetus and its family. Providing these services must be in the form of a multidisciplinary care provision team, and the family, which intends to continue the pregnancy, will have the opportunity to benefit from the services offered in the modern format of palliative care that is, perinatal palliative care.[5,7,11]

The World Health Organisation defines perinatal palliative care as providing care to a foetus with severe defects leading to death, and its family, and advises to prevent and relieve pain through early diagnosis, precise assessment and performing comprehensive foetus care with the aim of relief.[1] In 2010, England’s palliative care association described perinatal palliative care as programming and providing supportive care during life and in the final life stages for the foetus, the neonate and the family so as to better manage the undesirable conditions.[16] Although in some countries, numerous studies have been conducted on neonatal palliative care, perinatal palliative care is investigated less frequently. There are few studies conducted to identify and assess the possible challenges and problems of providing this type of care.[10]

Given the novelty of perinatal palliative care, especially in Iran, it is predicted that its provision will be accompanied by numerous challenges. Therefore, it seems evident that identifying and prioritising these challenges are of great importance to remove these obstacles and implement the plan,[10,11,17] Since implementing such care depends on the cooperation of care providers, to obtain their cooperation, the first step will be to gain an awareness of their attitudes and viewpoints.[4,14,17] On the other hand, the provision of perinatal palliative care is considered as one of the necessities, and one of the approaches, a feasibility study is an awareness of the viewpoints of the care providers.[4,14,17] Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the attitudes of care providers including obstetricians, paediatricians and midwives working in perinatal, obstetric and NICU wards of selected teaching hospitals in Tehran in 2019. Moreover, the challenges of providing palliative care from the perspective of these individuals have been examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study population included all the paediatricians, nurses and midwives who worked in NICUs, maternity wards and operating rooms. Then, the research samples were studied through convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria consisted of having direct contact with the infant and the family, working in NICUs, maternity wards and operating rooms, being willing to answer questions as well as being familiar with Farsi.

The proper sample size was calculated 385 to be based on Cochran’s sample size formula, with a maximum ratio of 50% and an accuracy of 5%. Finally considering 5% attrition rate, 400 samples were determined.

Study process

To assess the attitude of care providers toward the perinatal palliative care and the challenges of its provision, in addition to the questionnaire of demographic characteristics, a researcher-made questionnaire was used. First, through literature review and searching the keywords, perinatal palliative care, perinatal hospice, life limiting condition, attitude and challenge in the databases PubMed, Ovid and Science Direct, with the aim of finding English papers published in the recent 15 years and related to the current study, relevant studies were selected and reviewed. In addition, to find Farsi articles, literature review was done by searching through Farsi databases including SID and Magiran. Forty-nine articles were obtained, and the ones with available abstracts were used. The items of the questionnaires were developed by reviewing previous studies. At first, 87 items were gathered, 58 of which remained after assessing the validity and the reliability of the questionnaire as well as applying expert opinions. Twenty-six of these items were related to care providers’ attitude on perinatal palliative care questionnaire, and 32 related to the challenges of providing perinatal palliative care from care providers’ viewpoint.

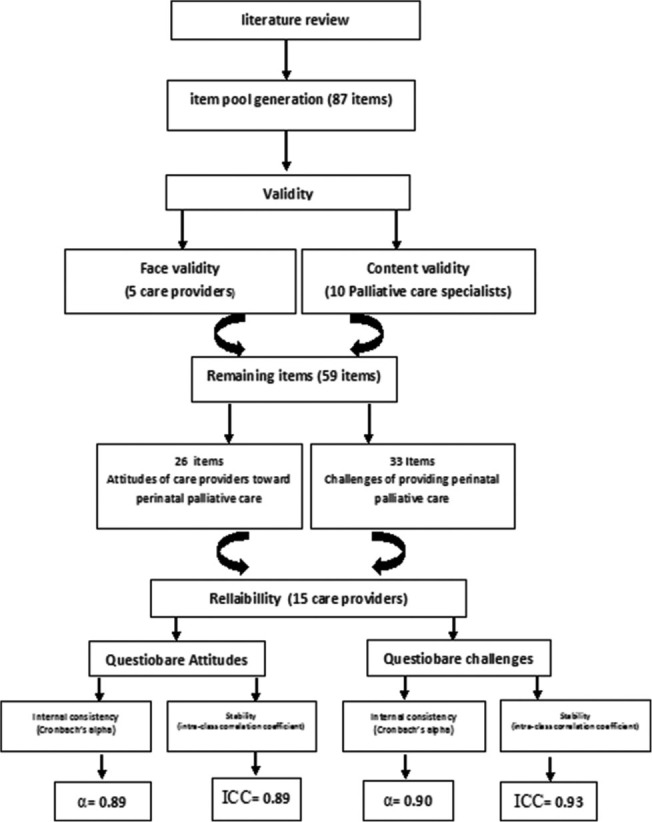

All the questionnaire’s items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from absolutely agree, agree, no idea, disagree and absolutely disagree. To confirm the content validity of the questionnaire, first, the questionnaire was provided to 10 palliative care professors and experts to collect their comments on whether the content of items is consistent with research objectives and it covers all the dimensions of the concept under study. To confirm the face validity, the questionnaire was provided to five subjects so that they would state their opinions regarding the understandability of the items and the ease of answering them. To assess the reliability, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and stability (intraclass correlation or ICC) were calculated on a sample of 15 care providers. To determine the stability of the instrument, the developed questionnaires were provided to 15 care providers within a 10-day interval, and the ICC was measured for the scores of test retest. The stages of developing the questionnaire and its validity and reliability are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of psychometric process two questionnaire attitude of care providers toward perinatal palliative care and challenges of perinatal palliative care providers.

In this study, after obtaining an ethical code and the permission to enter into research fields, the researcher referred to the teaching hospitals affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Mahdieh, Shohadaye Tajrish, Mofid and Imam Hussein hospitals), Tehran (paediatric medical centre) and Iran (Hazrate Ali Asghar hospital). Then, individuals who met the inclusion criteria were selected from among the paediatricians, gynaecologist, nurses and midwives who worked in NICUs, maternity wards and operating rooms. The questionnaires were provided to 385 individuals, and they were asked about the researcher’s next visit to receive the filled out questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

After collecting the questionnaires, the gathered data were entered into SPSS V21. To analyse the data, descriptive and inferential statistical tests were used. Considering the types of variables, Kruskal–Wallis and Chi-square tests were applied.

Ethical considerations

The researchers tried to follow all ethical principles. All study samples completed the questionnaires willingly. Before filling out the questionnaires, the study objectives were explained to them and they were told that they would receive the results by email in case they were willing to. The participants had the freedom to quit the study at any stage of the study. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Medical Sciences the code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1397.178.

RESULTS

Four hundred questionnaires were distributed among the research samples, 390 of which were finally completed. Therefore, the response rate was calculated to be 97.5%. The mean age of subjects was 35.32 ± 8.32 years and their mean working experience, 9.07 ± 7.22 years. Other demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Characteristics of care providers in the selected training hospitals at Tehran at 2019 (n=390).

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 51 | 13/1 | ||

| Female | 339 | 86/9 | ||

| Job | ||||

| Nurse | 205 | 52/5 | ||

| Midwife | 80 | 20/5 | ||

| Paediatrician | 56 | 14/4 | ||

| Gynaecologists | 37 | 9/5 | ||

| Neonatologist | 12 | 3/1 | ||

| Unit | ||||

| NICU | 265 | 67/9 | ||

| Operation room | 17 | 4/4 | ||

| Labour | 108 | 27/7 | ||

| Palliative care course | ||||

| Yes | 112 | 28/7 | ||

| No | 278 | 71/3 | ||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Age (year) | 35.34 | 8.32 | 22 | 60 |

| Work experience (year) | 9.7 | 7.22 | 1 | 30 |

Regarding the attitude of care providers, the results of the study showed that most of the care providers (90.5%) believed that parents should be involved in decision making on selecting the treatment type. In addition, 93.8% believed when a neonate dies, care providers should allocate enough time for speaking and sympathise with its family, and 85.1% believed that perinatal palliative care must be included in the medical curriculum. Besides, 43.1% of the participants did not find the physical environment of NICUs appropriate for the provision of perinatal palliative care. About 32.3% of them believed that there was not a sufficient number of staff in NICUs to provide this type of care. The other cases are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Attitude of the care providers on providing perinatal palliative care in the selected training hospitals at Tehran at 2019 (n=390).

| Items | Agree | No comment | Disagree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| It is necessary that parents be involved on decision making for the type of their neonate’s treatment | 353 | 90.5 | 23 | 5.9 | 14 | 3.6 |

| When the early death of the neonate is predicted, decline in neonate’s pain is preferred rather than other cares. | 329 | 84.4 | 31 | 7.9 | 30 | 7.7 |

| It is needed that palliative care to be a necessary part in the study course of nursery | 310 | 79.5 | 33 | 8.5 | 47 | 12.1 |

| It is needed that palliative care to be a necessary part of study course of medicine | 332 | 85.1 | 25 | 6.4 | 33 | 8.5 |

| When a neonate is expired in the ward, care providers should allocate sufficient time to talk with his/her family | 366 | 93.8 | 15 | 3.8 | 9 | 2.3 |

| It is required that health-care team state their comments, values and believes on perinatal palliative care. | 325 | 84.1 | 28 | 7.2 | 34 | 8.7 |

| It is necessary to provide trainings on communicating with and support neonates’ parents in final stages of life for care providers | 329 | 84.4 | 28 | 7.2 | 33 | 8.5 |

| When a neonate dies, the conditions should be provided for care providers to provide consulting services | 322 | 82.6 | 34 | 8.7 | 34 | 8.7 |

| Physical environment of NICUs is appropriate to provide palliative cares | 114 | 29.2 | 108 | 27.7 | 168 | 43.1 |

| In intensive care units, there are sufficient personnel to perform perinatal palliative care | 89 | 28.8 | 175 | 44.9 | 126 | 32.3 |

| Perinatal palliative care is inconsistent with the values of neonates care | 111 | 28.5 | 132 | 33.8 | 147 | 37.7 |

| The neonate must not die under any circumstances | 115 | 29.5 | 169 | 43.3 | 106 | 27.2 |

NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit

Regarding the challenges of providing perinatal palliative care, most of the care providers (90%) believed that ‘the lack of prepared infrastructures’ is one of the major challenges in providing this type of care.

In addition, 88.7% of the participants considered ‘parents’ insufficient knowledge of perinatal palliative care’ while 85.4% believed ‘the insufficient number of the staff providing this type of care’ to be a major challenge. On the other hand, 41.8% of the participants believed that ‘the inability of care providers in providing this type of care, despite having sufficient knowledge’ is not considered an obstacle to implement palliative care. In addition, 36.7% of them did not consider worrying about ‘the undesirable quality of services in case of providing this type of care’ as an important barrier to providing perinatal palliative care, to be a barrier. And finally, 35.3% of the subjects believed that ‘care providers’ preference to continue pregnancy until birth’ is not a major barrier [Table 3].

Table 3:

Challenges of providing perinatal palliative care from the viewpoint of care providers in selected training hospitals at Tehran at 2019 (n=390).

| Items | Agree | No comment | Disagree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Insufficient access to ethical committees of medicine during facing to ethical challenges | 304 | 77.9 | 35 | 9 | 51 | 13.1 |

| Deficiency of consultants and specialists of palliative cares field | 317 | 81.3 | 40 | 10.3 | 33 | 8.5 |

| Insufficient number of personnel | 333 | 85.4 | 36 | 9.2 | 21 | 5.4 |

| Insufficient knowledge of parents on perinatal palliative care | 346 | 88.7 | 33 | 8.5 | 11 | 2.8 |

| Not being ready of substructures to perform this care | 351 | 90 | 20 | 5.1 | 19 | 4.9 |

| Insufficient knowledge of care providers on perinatal palliative care | 329 | 84.4 | 32 | 8.2 | 29 | 7.4 |

| Insufficient number of physicians to provide perinatal palliative care | 320 | 82.1 | 43 | 11 | 27 | 6.9 |

| Insufficient access of families to psychological cares and spiritual support | 313 | 80.2 | 27 | 6.9 | 50 | 12.8 |

| Preferring continuing pregnancy until birth by the care providers | 137 | 35.1 | 115 | 29.5 | 138 | 35.3 |

| Wasting time in case of not treating diseases leading death with providing perinatal palliative care | 117 | 30 | 136 | 34.9 | 137 | 35.1 |

| Inability of perinatal palliative care providers to provide such services | 121 | 31 | 106 | 27.2 | 163 | 41.8 |

| Undesirable quality of providing perinatal palliative care by the care providers | 136 | 34.9 | 111 | 28.5 | 143 | 36.6 |

DISCUSSION

Although the primary idea of perinatal palliative care was presented in 1980, it was only noticed in recent years through the progress in the science and technology of caring for neonates as well as the development of NICUs.[14] The aim of implementing the perinatal palliative care program is to predict the demands of parents and the family in all the stages of pregnancy including the diagnosis of anomalies and decision-making on continuing pregnancy, planning during the stages of birth and delivery and the postnatal or post death period. Thus, unnecessary care provision and the pain and suffering of the neonate will be prevented, and the family’s quality of life and power of coping with these conditions will increase through providing spiritual, mental, social and physical support for the neonate and the family.[5,11]

Given the importance of care providers’ role, it seems necessary to study their attitudes and investigate the challenges against providing perinatal palliative care from their point of view. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to determine the attitude of care providers toward perinatal palliative care and the existing challenges in the selected teaching hospitals in Tehran in 2019. In this study, efforts have been done to survey all the groups which are in direct contact with the neonate or the foetus with foetal life-threatening defects and are providing them with care. This can be considered as one of the points of strength of the current study. It should be mentioned that just a limited number of studies conducted in the field of palliative care have studied the viewpoints of specific groups of care providers. For instance, in a study conducted in Poland with the aim of studying the viewpoint of care providers on the challenges of perinatal palliative care, just two groups of nurses and paediatricians in charge of NICUs were surveyed.[14] In addition, a study conducted in Australia with similar objectives, only included nurses.[10] Efficient implementation of perinatal palliative care requires communication and coordination among all specialists; therefore, it is necessary to collect comprehensive data on all these individuals.

In this study, most of the participants believed that parents should be involved in care provision and selecting the type of treatment. Besides, many studies conducted with the aim of identifying the challenges of providing palliative care for neonates from the viewpoint of care provision staff have emphasised this issue, too.[10,18,19] Caring for children and neonates should be family centred. It means that the family should be informed of the care process and decide about the way in which it will be provided. Therefore, this issue has been accepted as a caring principle.[8,11,20]

In contrast, in a study conducted, with the same aim, on NICU nurses in Egypt, only, 27.7% of the study samples believed in this principle. In the researchers’ opinion, the reason behind this difference might be the novelty of this type of care in Egypt. Another reason may be that not sufficient attention has yet been paid to this type of care by the care providers and the society.[21] In the present study, more than 90% of the care providers believed that when a neonate dies in the ward, care providers should allocate enough time to speak and empathise with its family. The more care providers connect with the family, the higher the quality of care provision.[19] In some studies, not allocating enough time to speak to the neonate’s family has been considered as one of the challenges in providing this type of care, which is in line with the finding of the present study.[19,22] Besides, in another study, only 38% of the participants believed so, which might be due to care providers’ insufficient time to provide care.[21]

In the present study, 43% of the participants did not find the physical environment of the NICUs appropriate for providing perinatal palliative care. In addition, some studies, such as the review study conducted in Iran, have also emphasised the inappropriateness of the physical environment of NICUs to provide this type of care.[10,11,23] An appropriate intensive care unit should provide enough space for the presence of the treatment team along with the neonate’s family to discuss and decide on the type of treatment. Besides, regarding light and noise, it must provide maximum comfort for the neonate for appropriate sleep, growth and development. Moreover, it needs to have skilled staff and definite guidelines and a private environment for the convenience of the parents and the family to express their feelings to the hospitalised neonate. However, it seems that the wards of the hospitals under study lacked all these properties.[11,12,16]

Most of the participants in the present study believed that when the death of the neonate is imminent, relieving its pain is a priority, which is in line with the viewpoints of most of the participants in the relevant studies.[10,18] In contrast, the findings of some other studies show that the belief that pain management in neonates is a priority at the end-of-life stages is not so much common.[5,8,9] The shortage of narcotics is one of the main obstacles on the way of applying this viewpoint.

Besides, opioid phobia prevents care providers from using this medication most of the time. According to the annual report of INCB committee, regarding the prevalence of narcotic use, Egypt ranks 116th, Kuwait, 86th and Iran, 148th globally. Thus, the shortage of narcotic medicines is considered as an important challenge against pain relief in patients at the end-of-life stages.[18,22] In addition, there are two common myths on neonates’ pain among care providers, claiming that neonates do not feel pain and that prescribing narcotics suppresses the immune system. Therefore, neonatal pain is neglected by care providers. In such cases, the required trainings on pain management and correct and appropriate use of narcotics must be provided for care providers.[5,8,9] Regarding the assessment of the challenges of providing perinatal palliative care, most care providers believed that ‘the lack of required infrastructures’ is one of the main challenges of providing this type of care. This is partially due to NICUs’ lack of preparation, insufficient consultants and specialists in this field, as well as the lack of definite guidelines in wards to provide this type of care.[10,11,24]

In the present study, more than 85% of the samples believed that there is not sufficient staff to perform this type of care, which is almost in line with all the conducted studies.[4,10,11,14,24] Brant et al. in 2019, through publishing an article entitled ‘The Assessment of the Roles, Satisfaction, and Obstacles of Home-Care Nurses in Providing Palliative Care,’ surveyed 532 nurses in 29 countries of the world on the challenges of providing palliative care. Based on their findings, they introduced five items as the important challenges of providing this type of care: The insufficiency of the staff providing care, insufficient budget, the lack of clear policies and guidelines regarding this type of care, the lack of access to care centres for patients at end-of-life stages as well as the society’s values and awareness of this type of care.[24]

The lack of sufficient nurses to provide care in hospitals and in the society is one of the most important challenges of health systems and health authorities in countries all over the world including Iran. Therefore, it is obvious that in such conditions, adding a specialised duty to routine care duties will add to this problem. The deficiency of human resources is considered a serious obstacle. Since it is necessary that care providers pass specialised courses in palliative care to be able to provide this type of care, holding such courses is not possible in all settings.[17] In this regard, more than 82% of the participants in this study believed that the insufficient knowledge of staff and parents is among the important challenges, which has been mentioned in numerous studies.[11,14,18,25] The reasons for the poor knowledge of staff include the lack of a cohesive training course in the curriculum of health care, the lack of time, the cost of passing such courses, the novelty of this type of care and lack of sufficient attention and sensitivity to this type of care.[24,26]

In the present study, about one-third of the participants had passed palliative care courses and had the knowledge. Therefore, it is necessary that health policymakers take the required measures in this regard. In Iran, due to the novelty of this type of care, formal university training in this field has not yet been initiated, and perinatal palliative care is not included in the curriculums of nursing and medicine. Although, in 2008, the master’s program for intensive care nursing was launched, and in spite of the fact that and the graduates of this field play an important role in providing care for neonates in NICUs, palliative care has not yet been incorporated into the curriculum of this discipline.[17,26,27] Regarding other conducted studies,[11,14,18] most of the participants of the present study believed that there is not sufficient access to the medical ethics committees and the experts in the field. When the diagnosis of abnormality in the pregnancy period becomes definite, the families are referred to palliative care team for decision making regarding the treatment. Therefore, this team should guide the families toward decisions which are not against ethical principles to help them. It is obvious that this team will need to consult with the ethics committee while dealing with ethical challenges and to solve them.[14]

One of the limitations of the present study is the lack of sufficient knowledge of the concepts related to palliative care on the part of care providers, which might affect their attitude in some cases. On the other hand, the lack of exposure to some of the criteria of providing palliative care may face them with problems in the identification of challenges.

CONCLUSION

According to the results of the current study, care providers have almost positive attitudes regarding various dimensions of providing perinatal palliative care, but, it has not been properly implemented yet due to the insufficient knowledge of this type of care, the lack of required infrastructures (appropriate conditions in NICUs to provide this type of care, the sufficient number of staff and experts in this field) as well as the health authorities’ neglecting this type of care.

Considering the attitudes and the limitations reported by care providers, it is necessary that the health system authorities pay special attention to this type of care and pave the way for the implementation of this type of care through holding training courses for care providers, recruiting sufficient staff and preparing the required infrastructures.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a Master’s thesis in neonatal intensive care nursing at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Hereby, the researchers appreciate all those who participated in the study.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Mohammadi A, Tahmasebi M, Mojen LK, Rassouli M, Ashrafizadeh H. Evaluation of care providers’ attitude toward perinatal palliative care and its challenges in the selected teaching hospitals of Tehran in 2019. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27:513-20.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors would like to appreciate the research deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Vol. 50. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2020. Improving the Quality of Care for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health in the WHO European Region. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmaelzadehsaeieh S, Zahmatkesh E, Rahimzadeh M, Azami N. Assessing the cause of prenatal mortality in medical centers of Alborz Province. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2016;26:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn P, Dillenseger L, Cojean N, Escande B, Zores C, Astruc D. Palliative care after neonatal intensive care: Contributions of Leonetti Law and remaining challenges. Arch Pediatr. 2016;24:155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghasemi F, Vafaenasab M, Firoozabadi ME, Sardadvar N, Zare M. Evaluating rate and causes of perinatal mortality in hospitals of Yazd Province in 2012. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2015;23:819–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catania TR, Bernardes LS, Benute GR, Cicaroni Gibeli MA, do Nascimento NB, Barbosa TV, et al. When one knows a fetus is expected to die: Palliative care in the context of prenatal diagnosis of fetal malformations. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:1020–31. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosello B, Dany L, Bétrémieux P, Le Coz P, Auquier P, Gire C, et al. Barriers in referring neonatal patients to perinatal palliative care: A French multicenter survey. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wool C, Northam S. The perinatal palliative care perceptions and barriers scale instrument©: Development and validation. Adv Neonatal Care. 2011;11:397–403. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e318233809a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter BS. Pediatric palliative care in infants and neonates. Children. 2018;5:21. doi: 10.3390/children5020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter BS, Brunkhorst J. Seminars in Perinatology. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. Neonatal pain management. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kain V, Gardner G, Yates P. Neonatal palliative care attitude scale: Development of an instrument to measure the barriers to and facilitators of palliative care in neonatal nursing. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e207–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmani N, Rassouli M, Mandegari Z, Bagheri I, Tafti BF. Palliative care in neonatal intensive care units: Challenges and solutions. Iran J Neonatol. 2018;9:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wool C. Clinician confidence and comfort in providing perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2013;42:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole JC, Moldenhauer JS, Jones TR, Shaughnessy EA, Zarrin HE, Coursey AL, et al. A proposed model for perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:904–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, Respondek-Liberska M, Przyslo L, Fendler W, Mlynarski W, Gulczynska E. Perinatal palliative care: barriers and attitudes of neonatologists and nurses in Poland. Sci World J. 2013;2013:168060. doi: 10.1155/2013/168060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wool C. Clinician perspectives of barriers in perinatal palliative care. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2015;40:44–50. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMahon DL, Twomey M, O'Reilly M, Devins M. Referrals to a perinatal specialist palliative care consult service in Ireland, 2012-2015. Arch Dis Childhood Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103:F573–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farahani AS, Rassouli M, Salmani N, Mojen LK, Sajjadi M, Heidarzadeh M, et al. Evaluation of health-care providers' perception of spiritual care and the obstacles to its implementation. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6:122. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_69_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Hajery M, Al-Mutairi H, Ayed A, Ayed M. Perception, knowledge and barriers to end of life palliative care among neonatal and pediatric intensive care physicians. J Palliat Care Med. 2018;8:326. doi: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilcullen M, Ireland S. Palliative care in the neonatal unit: Neonatal nursing staff perceptions of facilitators and barriers in a regional tertiary nursery. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:32. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parravicini E. Neonatal palliative care. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29:135–40. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ismail MS, Mahrous ES, Mokbel RA. Facilitators and barriers for delivery of palliative care practices among nurses in neonatal intensive care unit. Int J Nurs Health Sci. 2020;6:18–28. doi: 10.14445/24547484/IJNHS-V6I1P103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farahani AS, Rassouli M, Mojen LK, Ansari M, Ebadinejad Z, Tabatabaee A, et al. The feasibility of home palliative care for cancer patients: The perspective of Iranian nurses. Int J Cancer Manag. 2018;11:8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarmohammadi H, Mehr AJ, Sohrabi Y, Salimi H, Mohammadi A, Mohammadi E. The attitude of nurses in hospitals of kermanshah towards safety climate. Occup Hyg Health Promot. 2019;3:310–8. doi: 10.18502/ohhp.v3i4.2455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brant JM, Fink RM, Thompson C, Li YH, Rassouli M, Majima T, et al. Global survey of the roles, satisfaction, and barriers of home health care nurses on the provision of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:945–60. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silbermann M, Fink RM, Min SJ, Mancuso MP, Brant J, Hajjar R, et al. Evaluating palliative care needs in Middle Eastern countries. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:18–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forouzi MA, Banazadeh M, Ahmadi JS, Razban F. Barriers of palliative care in neonatal intensive care units: Attitude of neonatal nurses in Southeast Iran. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2017;34:205–11. doi: 10.1177/1049909115616597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadeghifar J, Bahadori M, Baldacchino D, Raadabadi M, Jafari M. Relationship between career motivation and perceived spiritual leadership in health professional educators: A correlational study in Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6:145. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n2p145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]