Key Points

Question

Are differences in treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits associated with racial or ethnic disparities in blood pressure (BP) control?

Findings

In this cohort study of 16 114 adults with hypertension, BP control was lowest among Black patients and highest among Asian patients, with White and Latinx patients having intermediate rates of BP control. Treatment intensification was associated with 21% to 26% of the observed racial differences in BP control, and missed visits were associated with 13% to 14% of the differences; scheduled follow-up interval was not a significant factor.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that ensuring that treatment intensification is provided more equitably could be a beneficial health care strategy to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in BP control.

Abstract

Importance

Black patients with hypertension often have the lowest rates of blood pressure (BP) control in clinical settings. It is unknown to what extent variation in health care processes explains this disparity.

Objective

To assess whether and to what extent treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits are associated with racial and ethnic disparities in BP control.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cohort study, nested logistic regression models were used to estimate the likelihood of BP control (defined as a systolic BP [SBP] level <140 mm Hg) by race and ethnicity, and a structural equation model was used to assess the association of treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits with racial and ethnic disparities in BP control. The study included 16 114 adults aged 20 years or older with hypertension and elevated BP (defined as an SBP level ≥140 mm Hg) during at least 1 clinic visit between January 1, 2015, and November 15, 2017. A total of 11 safety-net clinics within the San Francisco Health Network participated in the study. Data were analyzed from November 2019 to October 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Blood pressure control was assessed using the patient’s most recent BP measurement as of November 15, 2017. Treatment intensification was calculated using the standard-based method, scored on a scale from −1.0 to 1.0, with −1.0 being the least amount of intensification and 1.0 being the most. Scheduled follow-up interval was defined as the mean number of days to the next scheduled visit after an elevated BP measurement. Missed visits measured the number of patients who did not show up for visits during the 4 weeks after an elevated BP measurement.

Results

Among 16 114 adults with hypertension, the mean (SD) age was 58.6 (12.1) years, and 8098 patients (50.3%) were female. A total of 4658 patients (28.9%) were Asian, 3743 (23.2%) were Black, 3694 (22.9%) were Latinx, 2906 (18.0%) were White, and 1113 (6.9%) were of other races or ethnicities (including American Indian or Alaska Native [77 patients (0.4%)], Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander [217 patients (1.3%)], and unknown [819 patients (5.1%)]). Compared with patients from all racial and ethnic groups, Black patients had lower treatment intensification scores (mean [SD], −0.33 [0.26] vs −0.29 [0.25]; β = −0.03, P < .001) and missed more visits (mean [SD], 0.8 [1.5] visits vs 0.4 [1.1] visits; β = 0.35; P < .001). In contrast, Asian patients had higher treatment intensification scores (mean [SD], −0.26 [0.23]; β = 0.02; P < .001) and fewer missed visits (mean [SD], 0.2 [0.7] visits; β = −0.20; P < .001). Black patients were less likely (odds ratio [OR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.89; P < .001) and Asian patients were more likely (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; P < .001) to achieve BP control than patients from all racial or ethnic groups. Treatment intensification and missed visits accounted for 21% and 14%, respectively, of the total difference in BP control among Black patients and 26% and 13% of the difference among Asian patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that racial and ethnic inequities in treatment intensification may be associated with more than 20% of observed racial or ethnic disparities in BP control, and racial and ethnic differences in visit attendance may also play a role. Ensuring more equitable provision of treatment intensification could be a beneficial health care strategy to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in BP control.

This cohort study assesses whether and to what extent differences in treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits are associated with racial and ethnic disparities in blood pressure control among adults with hypertension.

Introduction

Approximately one-half of the US population has hypertension.1 Black populations are more likely than White populations to have hypertension, equally likely to be aware of hypertension and receive treatment for it, but less likely to achieve blood pressure (BP) control while receiving treatment.2,3 This racial disparity has been associated with higher rates of stroke and cardiovascular death among Black populations in the US.4,5 The underlying mechanisms associated with racial and ethnic disparities in BP control among patients with hypertension receiving routine primary care are not well understood.6 Differences in health care processes, such as treatment intensification for uncontrolled BP, frequency of follow-up visits scheduled by clinicians, and missed visits by patients, may play a substantial role and could present opportunities to design health care system interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. However, it is unclear to what extent variation in these 3 health care processes is associated with racial and ethnic disparities in BP control.

Other studies have previously assessed health care processes and their relative importance in improving BP control among patients with hypertension.7,8,9,10 Optimizing treatment intensification and follow-up interval could have a beneficial impact for improving BP control,11,12,13,14 but racial and ethnic variations in these factors have been underexamined, and their associations with racial and ethnic disparities in BP control have not been addressed. For example, the San Francisco Health Network has implemented ongoing interventions that have been associated with improvements in BP control among all patients, regardless of racial or ethnic group; however, the network continues to report lower BP control among Black patients.2 Hence, we do not know the extent to which racial or ethnic disparities in BP control are associated with differences in follow-up or treatment intensification.

In this study, we examined race- and ethnicity-specific differences in important health care processes that were system or practitioner dependent (scheduled follow-up interval and treatment intensification) and patient dependent (missed clinic visits), and we assessed the extent to which these processes were associated with racial or ethnic disparities in BP control.

Methods

This cohort study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco. Informed consent was waived because the study involved no more than minimal risk to participants, the waiver would not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the participants, and it would not have been practicable to obtain consent from such a large number of patients for a retrospective study. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Study Setting and Population

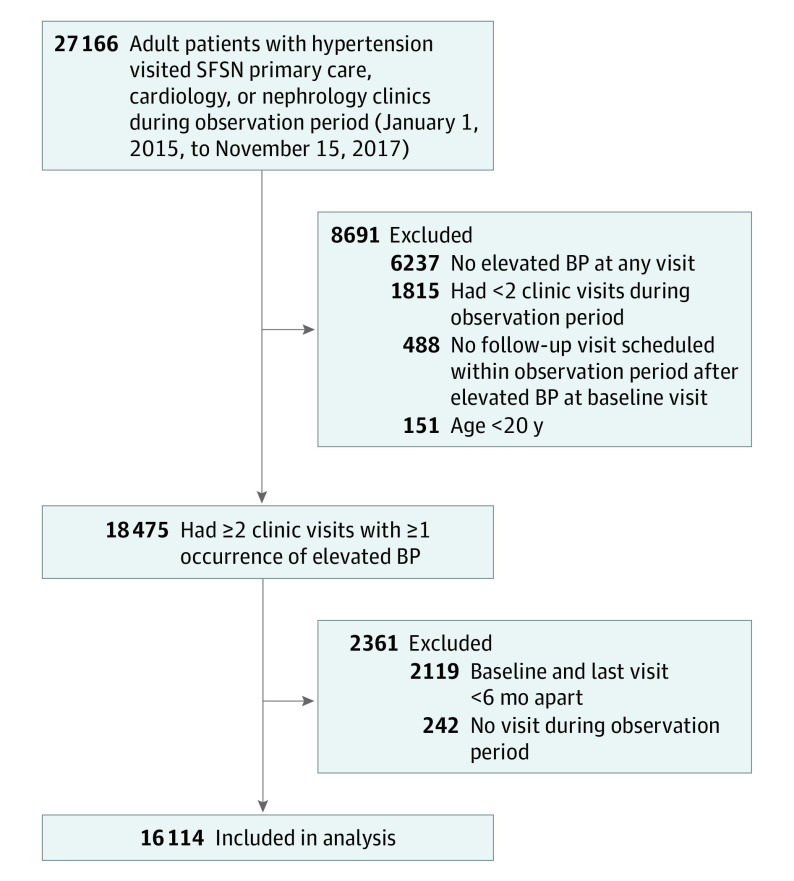

The study population comprised active patients who received care at 11 clinics within the San Francisco Health Network, a county-operated network of safety-net clinics, between January 1, 2014, and November 15, 2017. We included adult patients 20 years or older with either (1) a diagnosis of hypertension (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] code I10) in the electronic medical record (EMR) that was made either at their first visit or any time before their first visit or (2) at least 2 elevated BP measurements (defined as a systolic BP [SBP] level ≥140 mm Hg) between January 1, 2014, and January 1, 2015. Patients included in the study were also required to have attended at least 2 visits at San Francisco Health Network primary care, cardiology, or nephrology clinics during the observation period (January 1, 2015, to November 15, 2017), with elevated BP recorded during at least one of those visits. We defined the baseline visit as the first visit within the observation period during which elevated BP was recorded. Consistent with previous hypertension studies, we excluded patients with baseline and last visits that were less than 6 months apart,15,16 which ensured an appropriate follow-up period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram.

Elevated blood pressure (BP) was defined as a systolic BP level of 140 mm Hg or higher. SFSN indicates San Francisco Safety Network.

Measurements and Outcomes

Primary Outcome and Health Care Processes

The primary outcome was BP control, defined as an SBP level lower than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) level lower than 90 mm Hg at the most recent clinic visit within the observation period. Blood pressure levels were measured in the clinics using automated sphygmomanometers (OMRON 7 series; OMRON Healthcare, Inc), and measurements were repeated within 1 to 3 minutes whenever the first measurement indicated elevated BP. Fidelity to this protocol across sites was not assessed. We examined treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits, 3 health care processes that could potentially be associated with racial or ethnic disparities in BP control.

Treatment Intensification

Treatment intensification was measured using the standard-based method (SBM). We calculated the treatment intensification score as the number of visits during which medication changes occurred minus the number of visits during which elevated BP was recorded divided by the total number of clinic visits. Medication changes were defined as EMR prescription orders for new classes of antihypertensive medications or increases in dosing either at a visit during which elevated BP was recorded or between a visit during which elevated BP was recorded and the subsequent visit. Treatment intensification scores ranged from −1.0 to 1.0. A value of 0 indicated that treatment was intensified once for each visit during which elevated BP was recorded. A score greater than 0 signified that the number of visits during which treatment was intensified was greater than the number of visits during which elevated BP was recorded; a negative score signified that the number of visits during which elevated BP was recorded was greater than the number of visits during which treatment was intensified. A unit of 0.1 on this scale indicated either 1 more or 1 less occurrence of treatment intensification than expected per 10 visits. This measure has been reported to be the most consistently associated with BP control among commonly used treatment intensification measures.13

Scheduled Follow-up Interval and Missed Visits

The scheduled follow-up interval was defined as the mean number of days between a visit during which elevated BP was recorded and the next scheduled visit at any San Francisco Health Network primary care, cardiology, or nephrology clinic, regardless of whether the patient attended that visit. A missed visit was defined as nonattendance without notification (ie, a no-show) for a primary care, cardiology, or nephrology clinic visit within 4 weeks after any visit during which elevated BP was recorded and before the next visit. A canceled or rescheduled appointment was not considered a missed visit. Based on hypertension clinical guidelines, which recommend a follow-up interval of 2 to 4 weeks,17,18 our measure aimed to capture visits that were scheduled by the practitioner at the recommended follow-up interval but missed by the patient.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patients were classified into 5 racial and ethnic groups (Asian, Black, Latinx, White, and other race or ethnicity [including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unknown]) based on races and ethnicities recorded in the EMR. Other demographic characteristics included sex and age. We identified diabetes diagnoses based on ICD-10-CM codes in the EMR and the number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed at baseline. The primary care clinic to which the patient made the most visits during the observation period was considered the patient’s clinic.

Statistical Analysis

We reported summary statistics for all patients and for each racial and ethnic group separately (Table 1 and Table 2) using proportions for categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables. Analysis of variance and Pearson χ2 tests were used to assess differences between racial and ethnic groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension Within a Network of Safety-Net Clinics in San Franciscoa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Asian | Black | Latinx | White | Other race or ethnicityb | |

| Total patients, No.c | 16 114 | 4658 | 3743 | 3694 | 2906 | 1113 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.6 (12.1) | 62.1 (11.1) | 56.7 (11.4) | 57.1 (13.8) | 58.2 (10.8) | 57.0 (12.6) |

| 20-34 | 606 (3.8) | 82 (1.8) | 156 (4.2) | 217 (5.9) | 89 (3.1) | 62 (5.6) |

| 35-64 | 11 015 (68.4) | 2865 (61.5) | 2831 (75.6) | 2457 (66.5) | 2079 (71.5) | 783 (70.4) |

| 65-79 | 3837 (23.8) | 1434 (30.8) | 666 (17.8) | 823 (22.3) | 684 (23.5) | 230 (20.7) |

| ≥80 | 656 (4.1) | 277 (5.9) | 90 (2.4) | 197 (5.3) | 54 (1.9) | 38 (3.4) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 8098 (50.3) | 2769 (59.4) | 1675 (44.8) | 2044 (55.3) | 1053 (36.2) | 557 (50.0) |

| Male | 8016 (49.7) | 1889 (40.6) | 2068 (55.2) | 1650 (44.7) | 1853 (63.8) | 556 (50.0) |

| Diabetes | 5653 (35.1) | 1789 (38.4) | 1181 (31.6) | 1542 (41.7) | 719 (24.7) | 422 (37.9) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 150.1 (13.3) | 150.4 (12.5) | 151.3 (14.6) | 149.7 (13.0) | 148.8 (12.2) | 150.4 (14.9) |

| Diastolic | 86.8 (18.3) | 84.6 (21.0) | 89.4 (18.1) | 86.2 (20.9) | 87.0 (10.6) | 87.6 (11.2) |

| Stage of uncontrolled hypertensiond | ||||||

| 1 | 12 578 (78.1) | 3735 (80.2) | 2676 (71.5) | 2960 (80.1) | 2345 (80.7) | 862 (77.4) |

| 2 | 2759 (17.1) | 757 (16.3) | 793 (21.2) | 579 (15.7) | 447 (15.4) | 183 (16.4) |

| Severe | 777 (4.8) | 166 (3.6) | 274 (7.3) | 155 (4.2) | 114 (3.9) | 68 (6.1) |

| Antihypertensive medication classes prescribed, No. | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.3) |

| 0 | 4841 (30.0) | 1192 (25.6) | 996 (26.6) | 1243 (33.6) | 1098 (37.8) | 312 (28.0) |

| 1 | 4326 (26.8) | 1369 (29.4) | 921 (24.6) | 1014 (27.4) | 743 (25.6) | 279 (25.1) |

| 2 | 3680 (22.8) | 1156 (24.8) | 866 (23.1) | 793 (21.5) | 588 (20.2) | 277 (24.9) |

| 3 | 2113 (13.1) | 628 (13.5) | 567 (15.1) | 431 (11.7) | 332 (11.4) | 155 (13.9) |

| ≥4 | 1154 (7.2) | 313 (6.7) | 393 (10.5) | 213 (5.8) | 145 (5.0) | 90 (8.1) |

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Baseline was defined as the date of the patient’s first visit during which elevated BP was recorded.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native (77 patients [0.4%]), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (217 patients [1.3%]), and unknown (819 patients [5.1%]).

Includes adult patients with diagnosed hypertension who had 1 or more visit during which elevated SBP (≥140 mm Hg) was recorded between 2015 and 2017 and at least 2 visits during which elevated BP was recorded in the last 12 months.

Uncontrolled hypertension was defined as an SBP level of 140 mm Hg or higher. Stage 1 was defined as a systolic BP (SBP) level of 140 mm Hg to 159 mm Hg; stage 2 as an SBP level of 160 mm Hg to 179 mm Hg; and severe hypertension as an SBP level of 180 mm Hg or higher.

Table 2. Health Care Processes Associated With Racial Differences in Blood Pressure and Blood Pressure Control Among Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension at Baselinea.

| Health care process | Mean (SD) | P valuec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 16 114) | Asian (n = 4658) | Black (n = 3743) | Latinx (n = 3694) | White (n = 2906) | Other race or ethnicity (n = 1113)b | ||

| Total visits completed | 12.3 (9.0) | 11.9 (7.8) | 13.1 (10.1) | 12.6 (9.4) | 12.1 (9.0) | 11.6 (8.3) | <.001 |

| Patients with controlled BP, No. (%) | |||||||

| At last visit | 11 587 (71.9) | 3527 (75.7) | 2475 (66.1) | 2682 (72.6) | 2095 (72.1) | 808 (72.6) | <.001d |

| At last 3 visits | 11 580 (71.9) | 3532 (75.8) | 2427 (64.8) | 2667 (72.2) | 2163 (74.4) | 791 (71.1) | <.001 |

| Change in SBP, mm Hge | 17.5 (18.8) | 18.5 (17.8) | 16.8 (20.5) | 17.1 (18.2) | 17.1 (18.4) | 17.5 (19.6) | <.001 |

| Change in DBP, mm Hgf | 8.2 (19.0) | 8.0 (21.0) | 8.8 (19.6) | 7.9 (21.3) | 7.9 (12.4) | 8.4 (12.7) | .16 |

| Scheduled follow-up interval, dg | 67.2 (75.4) | 71.5 (73.1) | 56.9 (62.7) | 66.3 (75.5) | 73.2 (87.3) | 71.3 (85.7) | <.001 |

| Missed visits within 4 wk after elevated BP | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.8 (1.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Treatment intensification scoreh | −0.29 (0.25) | −0.26 (0.23) | −0.33 (0.26) | −0.30 (0.24) | −0.30 (0.26) | −0.30 (0.25) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Blood pressure control (SBP <140 mm Hg) was defined based on the BP level measured at the last clinic visit attended by the patient within the observation period of January 1, 2015, to November 15, 2017. Uncontrolled hypertension was defined as an SBP level of 140 mm Hg or higher.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unknown race or ethnicity.

The P value was calculated using an analysis of variance to test the difference in means between the 5 different racial and ethnic groups.

Because BP control at the last visit was a categorical variable, the P value was calculated using a Pearson χ2 test.

Change in SBP was calculated as the difference in SBP between the baseline and last visits.

Change in DBP was calculated as the difference in DBP between the baseline and last visits.

Scheduled follow-up interval was calculated as the mean number of days between a visit during which elevated BP was recorded and the next scheduled visit.

Treatment intensification score was calculated based on the standard-based method (ie, visits with medication changes minus visits with elevated BP divided by number of clinic visits).

Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the association between race or ethnicity and BP control at the last clinic visit. We adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis of diabetes, baseline SBP level, and baseline number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed. Clinic fixed effects were included to account for correlation within clinics and heterogeneity in observable and unobservable clinic characteristics, such as size, patient demographic characteristics, and practice patterns, that did not change during the observation period. With the inclusion of fixed effects, our estimates represented mean within-clinic estimates of the association between race or ethnicity and BP control. The 3 health care processes of interest (treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits) were subsequently added as covariates to the logistic regression model to examine the attenuation of the association between race or ethnicity and the primary outcome.

To assess the association of treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits with racial or ethnic differences in BP control, we used a generalized structural equation model with 100-replication bootstrapping.19 Our model was built as a system of 3 linear regression models that estimated the association between race and/or ethnicity and each of the 3 health care processes and 1 logistic regression model that assessed the association between race and/or ethnicity and BP control, adjusted for the 3 health care processes. Each equation was also adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis of diabetes, baseline SBP level, number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed, and clinic fixed effects. The analysis allowed calculation of mediation effects, including direct effects (ie, effect of race or ethnicity on BP control), indirect effects (ie, effect of race or ethnicity on health care processes, then health care processes on BP control), and total effects (ie, direct plus indirect effects). The proportion explained was calculated as the indirect mediation effect divided by the total mediation effect.20

To ensure the reliability of our primary outcome, we compared it with a commonly recommended alternative definition of BP control (mean BP level across the last 3 visits).21 We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who achieved BP control without any treatment intensification to account for potential misidentification of uncontrolled hypertension (ie, incorrect identification of elevated BP). We also excluded patients who had at least 2 visits at cardiology or nephrology clinics during the observation period as potential proxy measures for cardiac or chronic kidney disease. This exclusion was made because patients with heart failure and end-stage kidney disease, in particular, may have different BP goals and require special treatment considerations. We then replicated our analyses excluding Asian patients, the group with the highest BP control rate.

All data were analyzed between November 2019 and October 2020, using Stata software, version 15 (StataCorp LLC). The significance threshold was P = .05.

Results

Among 27 166 adult patients with hypertension who visited SFSN primary care, cardiology, or nephrology clinics during the observation period, 18 475 had 2 or more clinic visits with 1 or more occurrence of elevated BP. Of those, 16 114 patients (mean [SD] age, 58.6 [12.1] years; 8098 women [50.3%] and 8016 men [49.7%]) who had baseline and last visits that were 6 or more months apart were included in the analysis (Figure 1; Table 1). A total of 4658 patients (28.9%) were Asian, 3743 (23.2%) were Black, 3694 (22.9%) were Latinx, 2906 (18.0%) were White, and 1113 (6.9%) were of other races and ethnicities (American Indian or Alaska Native [77 patients (0.4%)], Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander [217 patients (1.3%)], and unknown [819 patients (5.1%)]). At baseline (ie, the first visit during which elevated BP was recorded), the mean (SD) SBP level was 150.1 (13.3) mm Hg, the mean (SD) DBP level was 86.8 (18.3) mm Hg, and 12 578 patients (78.1%) had stage 1 hypertension (SBP level of 140-159 mm Hg or DBP level of 90-99 mm Hg) (Table 1). Black patients had higher stages of uncontrolled hypertension at baseline compared with the overall study population, with a lower prevalence of stage 1 hypertension (2676 patients [71.5%] vs 12 578 patients [78.1%]) and a higher prevalence of severe hypertension (274 patients [7.3%] vs 777 patients [4.8%]). Racial and ethnic distribution varied by clinic. Among the primary care clinics included in the study, the highest proportion of Asian patients in a clinic was 92.8%; this clinic also had the highest reported BP control rate at 80.2% (eFigure 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Over a mean (SD) observation period of 25.2 (7.6) months (median, 27.3 months; IQR, 19.7-31.7 months), 11 587 patients (71.9%) had BP control at their last visit, a higher percentage than the mean BP control rate of 48.2% among the general population of adults in the US.22 In general, Black patients attended more visits than patients from all racial and ethnic groups (mean [SD], 13.1 [10.1] visits vs 12.3 [9.0] visits; P < .001) (Table 2). At the last visit, Black patients had the lowest rate of BP control (2475 patients [66.1%]), and Asian patients had the highest rate of BP control (3527 patients [75.7%]; P < .001). A similar difference was observed using an alternative definition of BP control that was based on mean BP measurements across 3 visits (2427 Black patients [64.8%] vs 3532 Asian patients [75.8%]; P < .001). Black patients had the smallest change in SBP between baseline and the last observed visit (16.7 mm Hg), and Asian patients had the largest (18.5 mm Hg; P < .001).

Significant racial and ethnic differences were observed in scheduled follow-up intervals, missed visits, and treatment intensification. Compared with all patients, Black patients had the shortest interval to scheduled follow-up (mean [SD], 56.9 [62.7] days vs 67.2 [754] days; P < .001) (Table 2). The number of missed visits was highest among Black patients (mean [SD], 0.8 [1.5] visits; β = 0.35) and lowest among Asian patients (mean [SD], 0.2 [0.7] visits; β = −0.20) compared with all patients (mean [SD], 0.4 [1.1] visits; P < .001). The treatment intensification score was highest among Asian patients (mean [SD], −0.26 [0.23]; β = 0.02) and lowest among Black patients (mean [SD], −0.33 [0.26]; β = −0.03) compared with all patients (mean [SD], −0.29 [0.25]; P < .001). Summary statistics for the different components of the SBM treatment intensification score (eTable 2 in the Supplement) revealed that the number of visits during which elevated BP was recorded but treatment intensification did not occur was highest among Black patients (mean [SD], 3.9 [4.1] visits) compared with White patients (mean [SD], 3.0 [3.1] visits; P < .001).

After adjusting for baseline BP, the number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed, age, sex, diabetes status, and clinic (model 1), Black patients were less likely than White patients to have BP control at the last visit (odds ratio [OR], 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.90; P < .001) (Table 3). In contrast, Asian patients were more likely than White patients to have BP at goal levels (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.05-1.33; P = .005). These differences were attenuated by adding treatment intensification score, missed visits, and scheduled follow-up interval (model 2). After adjusting for these 3 health care processes, the likelihood of BP control remained significantly lower among Black vs White patients (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.98; P = .02), but the difference between Asian and White patients was no longer statistically significant (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.99-1.27; P = .06). Overall, patients with higher baseline SBP levels were less likely to achieve BP control (model 1: OR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.98-0.98; P < .001]; model 2: OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < .001]) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Likelihood of Blood Pressure Control by Race at the Last Visit During the Observation Perioda.

| Race or ethnicity | BP control, OR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1c | Model 2d | |

| Asiane | 1.18 (1.05-1.33) | 1.12 (0.99-1.27) |

| Black | 0.80 (0.72-0.90)f | 0.87 (0.77-0.98)g |

| Latinx | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other race or ethnicityh | 1.08 (0.92-1.27) | 1.08 (0.92-1.27) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; OR, odds ratio.

Results from logistic regression analyses estimating the association between race and the probability of having controlled BP (systolic BP <140 mm Hg) at the last observed primary care visit between January 1, 2015, and November 15, 2017.

Odds ratios for all variables in the models are available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Model 1 was adjusted for baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed, age, sex, presence of diabetes, and clinic fixed effects.

Model 2 was adjusted for all variables in model 1 plus scheduled follow-up interval, treatment intensification score, and missed visits.

P = .005.

P < .001.

P = .02.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unknown race or ethnicity.

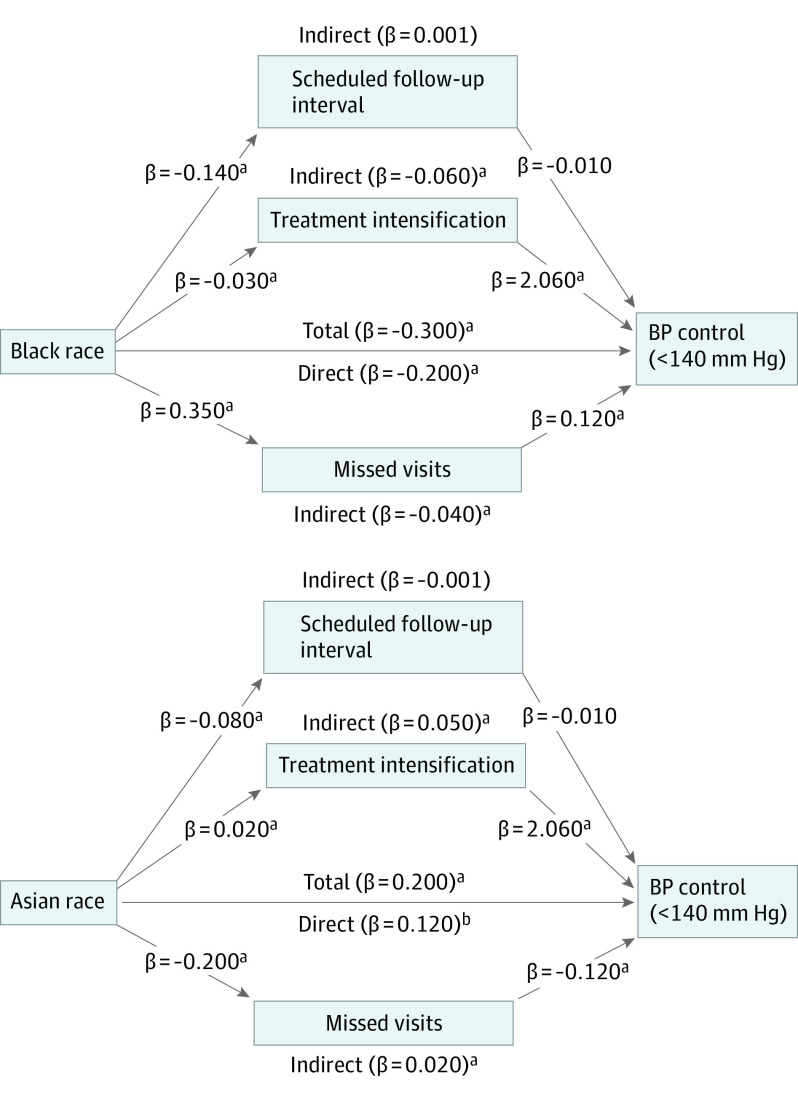

Our mediation analysis revealed that both treatment intensification and missed visits were significant factors in the association between Asian and Black race and BP control (Figure 2). Black race was associated with a lower probability of BP control compared with all other races and ethnicities (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.89; β = −0.30; P < .001); 21% of the total mediation effect was associated with treatment intensification and 14% was associated with missed visits. Treatment intensification accounted for 26% of the total mediation effect in the association between Asian race and BP control (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; β = 0.20; P < .001), whereas missed visits accounted for 13%. The scheduled follow-up interval was longer among Asian patients (β = 0.08; P < .001) and shorter among Black patients (β = −0.14; P < .001) compared with the other racial and ethnic groups but was not a significant factor in the association between Asian or Black race and BP control (Asian race: OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 1.00-1.00]; Black race: OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 1.00-1.00]). An additional analysis (eFigure 5 in the Supplement) revealed that Black patients also had a significantly lower reduction in SBP level between baseline and the last visit compared with the other racial and ethnic groups (β = −1.03; P = .003). In contrast, the difference in SBP reduction between baseline and last visit was not statistically significant (β = 0.46; P = .16).

Figure 2. Association of Black and Asian Race With Blood Pressure Control.

Coefficients from a generalized structural equation model estimating the association of Black and Asian race (vs all other races and ethnicities, including Latinx, White, and other [American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unknown]) with blood pressure (BP) control at the last clinic visit, mediated by treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed visits.

aP < .001.

bP = .009.

In the prespecified sensitivity analyses, we found similar results after excluding patients who had at least 2 visits at cardiology or nephrology clinics (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement) and patients who achieved BP control without any treatment intensification (eTable 6 and eTable 7 in the Supplement). Results from the logistic regression analyses are presented in eTable 8, eTable 9, eFigure 2, and eFigure 3 in the Supplement. We also found similar results after excluding the Asian patient subgroup (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This cohort study examined the extent to which 3 health care processes (treatment intensification, scheduled follow-up interval, and missed clinic visits) were associated with racial or ethnic disparities in achieving BP control among patients with elevated BP receiving care at 11 SFHN safety-net clinics. We found that disparities in treatment intensification by race may be an important health care process associated with racial or ethnic disparities in BP control. Missed visits by patients were also associated with disparities, albeit to a lesser extent. Black patients had the lowest rates of BP control, which persisted after controlling for higher baseline severity of elevated BP, whereas Asian patients had the highest rates of BP control; however, the association between race and BP control was attenuated among Black patients and no longer statistically significant among Asian patients when controlling for treatment intensification.

Although clinical inertia (ie, missed opportunities for treatment intensification among practitioners) has been documented as an important barrier to achieving higher rates of BP control, the evidence for racial bias in clinical inertia is mixed, and the association between clinical inertia and racial or ethnic disparities in BP control has not been well examined.6 In contrast to our findings, 2 studies have reported no difference in clinical inertia based on patient race.3,23 This difference in findings may be explained by the fact that our study used the SBM to measure treatment intensification, which performs better than other methods for measuring the association of treatment intensification with BP control.13,24 Consistent with our findings, a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial that implemented a physician educational intervention at a single clinic reported lower treatment intensification among Black patients compared with White patients using the SBM.6

Our study made several additions to the literature. We examined racial and ethnic differences in treatment intensification using the SBM and assessed the association of clinical inertia with racial or ethnic disparities in BP control.25 We found differences in BP control and treatment intensification for hypertension in both Asian and Black patients compared with patients from other racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that disparities in treatment intensification may be the primary factor associated with both better and worse BP control rates. Ensuring equity in treatment intensification may be a reasonable focus for both clinicians and health care systems in their efforts to improve BP control in an equitable manner.

Addressing inequities in treatment intensification, however, requires a better understanding of why differences in treatment intensification exist. It is possible that Black patients disproportionately receive care from clinicians who are less likely to intensify treatment. Clinicians may be less likely to intensify medication therapy for Black patients because of bias in their beliefs about patients’ nonadherence to medications, financial strain, or lifestyle risk factors.6,26 Black patients may also have greater distrust of clinicians and might be more likely to resist medication for the treatment of elevated BP.27,28 Based on many cultural traditions, Asian patients may show greater deference to physicians and health care institutions with regard to treatment decisions.29,30 Given these challenges, efforts to address racial and ethnic inequities in treatment intensification may need to consider cultural differences and take a 2-pronged approach that addresses clinicians’ prescribing behavior and assists patients in understanding and participating in treatment decisions for elevated BP. A potential solution may be the use of EMR-embedded clinical decision support tools. Such tools could facilitate team-based care and empower patients to participate, communicate, and nudge their clinicians toward more frequent and individualized treatment intensification.31,32

Our finding that racial differences in missed visits were associated with disparities in BP outcomes was not unexpected. Previous studies have reported higher rates of no-shows among Black patients.33,34,35 However, it is worth noting that Black patients in our sample attended more total visits at shorter intervals than patients from other racial and ethnic groups, despite the higher rate of missed visits. We therefore suspect that missed visits were not directly associated with racial or ethnic disparities in BP control. Rather, higher rates of missed visits among Black patients may be a marker for other factors that are generally associated with worse health and may be more directly associated with BP control. For example, medication nonadherence has been associated with low visit attendance.36 Low literacy levels, limited transportation, lack of insurance or suboptimal medication coverage, and competing health care priorities because of comorbid conditions have also been reported as important risk factors associated with missed visits among Black patients34,36; however, it is unclear the extent to which these factors differed by race and ethnicity within our study population of patients with low income receiving care at safety-net clinics.6,25 To address the issue of missed visits, health care systems and clinics have adopted interventions, such as mail and telephone reminders, text messages, patient educational programs, and incentives for attending appointments, with some success.36 However, our findings in the context of previous studies suggest that more effort is needed to address underlying risk factors for missed visits rather than simply focusing on reducing the number of no-shows. To this end, strategic efforts might include providing weekend clinic hours, transportation reimbursement, and patient-centered approaches that emphasize team-based care delivery whereby patients can receive treatment for hypertension via telehealth visits, in the communities where they live (eg, neighborhood pharmacies, barber and beauty shops, and churches), or during visits with specialists or nonphysician practitioners, such as nurses or pharmacists.37,38,39,40

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths. The longitudinal cohort design enabled us to account for baseline BP, mitigating potential confounding from the higher baseline severity of elevated BP among Black patients.

This study also has limitations. Our data could not capture medication adherence, which has been reported to be lower among Black patients and potentially associated with BP control.3,27,41 Although future analyses may assess the relative importance of medication adherence to racial disparities in BP control, multiple studies have found that treatment intensification and visit frequency are important factors associated with BP control, independent of medication adherence.13,42 Our study was not designed to examine factors associated with treatment intensification, including medication adherence. Although a previous study found that medication adherence was not independently associated with treatment intensification,33 the interaction between clinician decisions and medication adherence as well as other socioeconomic factors, such as access to transportation, life stressors, and the ability to pay for health services, warrant further investigation. Additional studies are needed to understand how socioeconomic differences, even within low-income populations receiving care at safety-net clinics, could partially explain differences in treatment intensification and missed visits.

Because our data did not capture comorbid conditions other than diabetes, we did not account for racial and ethnic differences in heart failure and end-stage kidney disease. However, our findings were replicated in sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who had consistently received care from cardiologists or nephrologists. In addition, although our analyses were adjusted for age and the number of antihypertensive medication classes prescribed at baseline, we did not have data regarding when patients were first diagnosed with hypertension, which may be associated with BP control.

It is beyond the scope of this analysis to consider the differences in the processes of care and BP control rates that may exist between individual practitioners within a clinic. Our data were limited by the inability to reliably identify individual practitioners. Furthermore, our clinic network generally uses team-based models, in which patients often receive care from other practitioners in the care team, which may affect decisions about treatment intensification and follow-up. In addition, our data do not include demographic and other characteristics of clinicians that would be important to investigate practitioner-level differences in racial and ethnic inequities. Our study was conducted in a single health care network within a single city, thereby potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings, particularly with regard to rural areas.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, inequities in treatment intensification and missed visits were associated with racial disparities in BP control. The findings suggest that prescribing appropriate medication therapy to Black patients when they present with elevated BP could substantially reduce racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension control. Interventions that target factors associated with missed visits may also be important. Taken together, these 2 strategies could substantially reduce racial and ethnic disparities in BP control.

eTable 1. Blood Pressure Control and Health Care Processes by Clinic

eTable 2. Process Measurements for Treatment Intensification (TI), Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Likelihood of Blood Pressure Control (<140/90 mm Hg) at the Last Visit During the Observation Period After Adjusting for Race

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension (HTN) Within a Network of Safety-Net Clinics in San Francisco, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 5. Racial Differences in Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) and Potential Mediators of BP Control Among Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension at Baseline, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension (HTN) Within a Network of Safety-Net Clinics in San Francisco, Excluding Patients Whose Blood Pressure (BP) Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eTable 7. Racial Differences in Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) and Potential Mediators of BP Control Among Patients With Hypertension at Baseline, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eTable 8. Likelihood of Blood Pressure Control (<140/90 mm Hg) by Race at the Last Visit During the Observation Period, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 9. Likelihood of Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) by Race at the Last Visit During the Observation Period, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eFigure 1. Racial Distribution by Clinic

eFigure 2. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black and Asian Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eFigure 3. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black and Asian Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eFigure 4. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits, Excluding Asian Patients

eFigure 5. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black Race With Change in Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits

References

- 1.American Heart Association. 2021 Heart disease and stroke statistics update fact sheet at-a-glance. American Heart Association; 2021. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://www.heart.org/-/media/phd-files-2/science-news/2/2021-heart-and-stroke-stat-update/2021_heart_disease_and_stroke_statistics_update_fact_sheet_at_a_glance.pdf

- 2.Fontil V, Gupta R, Moise N, et al. Adapting and evaluating a health system intervention from Kaiser Permanente to improve hypertension management and control in a large network of safety-net clinics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(7):e004386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umscheid CA, Gross R, Weiner MG, Hollenbeak CS, Tang SSK, Turner BJ. Racial disparities in hypertension control, but not treatment intensification. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(1):54-61. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES. Trends in mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease among hypertensive and nonhypertensive adults in the United States. Circulation. 2011;123(16):1737-1744. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lackland DT. Racial differences in hypertension: implications for high blood pressure management. Am J Med Sci. 2014;348(2):135-138. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kressin NR, Orner MB, Manze M, Glickman ME, Berlowitz D. Understanding contributors to racial disparities in blood pressure control. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):173-180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.860841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellows BK, Ruiz-Negron N, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Clinic-based strategies to reach United States Million Hearts 2022 blood pressure control goals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(6):e005624. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant KB, Sheppard JP, Ruiz-Negron N, et al. Impact of self-monitoring of blood pressure on processes of hypertension care and long-term blood pressure control. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(15):e016174. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chale-Rush A, Guralnik JM, Walkup MP, et al. Relationship between physical functioning and physical activity in the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders pilot. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1918-1924. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03008.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontil V, Bibbins-Domingo K, Nguyen OK, Guzman D, Goldman LE. Management of hypertension in primary care safety-net clinics in the United States: a comparison of community health centers and private physicians’ offices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):807-825. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W, Goldberg SI, Shubina M, Turchin A. Optimal systolic blood pressure target, time to intensification, and time to follow-up in treatment of hypertension: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthmann R, Davis N, Brown M, Elizondo J. Visit frequency and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(6):327-332. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04371.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan BM, Li J, Sutherland SE, Rakotz MK, Wozniak GD. Hypertension control in the United States 2009 to 2018: factors underlying falling control rates during 2015 to 2018 across age- and race-ethnicity groups. Hypertension. 2021;78(3):578-587. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper LB, Lu D, Mentz RJ, et al. Cardiac transplantation for older patients: characteristics and outcomes in the septuagenarian population. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(3):362-369. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chenier M, Patel KK, Svensson LG, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with postoperative cardiovascular pseudoaneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(1):43-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.08.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McManus RJ, Mant J, Bray EP, et al. Telemonitoring and self-management in the control of hypertension (TASMINH2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):163-172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60964-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal A, Bornstein WA. Health system–wide quality programs to improve blood pressure control. JAMA. 2013;310(7):695-696. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaney T, Schutte AE, Stergiou GS, et al. ; MMM Investigators . May Measurement Month 2019: the global blood pressure screening campaign of the International Society of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76(2):333-341. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593-614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ditlevsen S, Christensen U, Lynch J, Damsgaard MT, Keiding N. The mediation proportion: a structural equation approach for estimating the proportion of exposure effect on outcome explained by an intermediate variable. Epidemiology. 2005;16(1):114-120. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147107.76079.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential U.S. population impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):109-118. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana J, Oldroyd J, Islam MM, Tarazona-Meza CE, Islam RM. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension among United States adults: evidence from NHANES 2017-18 survey. Int J Cardiol Hypertens. 2020;7:100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shelley D, Tseng TY, Andrews H, et al. Predictors of blood pressure control among hypertensives in community health centers. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(12):1318-1323. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):345-351. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200702.76436.4b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings DM, Adams A, Halladay J, et al. Race-specific patterns of treatment intensification among hypertensive patients using home blood pressure monitoring: analysis using defined daily doses in the Heart Healthy Lenoir study. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(4):333-340. doi: 10.1177/1060028018806001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Hanratty R, et al. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):987-995. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2795-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenthaler A, Montague E, Baier Manwell L, Brown R, Schwartz MD, Linzer M. Patient-physician racial/ethnic concordance and blood pressure control: the role of trust and medication adherence. Ethn Health. 2014;19(5):565-578. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.857764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin KD, Roter DL, Beach MC, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Physician communication behaviors and trust among Black and White patients with hypertension. Med Care. 2013;51(2):151-157. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827632a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(2):116-126. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.2.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilchaikovit T, Hill JM, Holland JC. The effects of culture on illness behavior and medical care. Asian and American differences. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15(1):41-50. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90090-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omboni S, Caserini M, Coronetti C. Telemedicine and m-health in hypertension management: technologies, applications and clinical evidence. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2016;23(3):187-196. doi: 10.1007/s40292-016-0143-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vuppala S, Turer CB. Clinical decision support for the diagnosis and management of adult and pediatric hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(9):67. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01083-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(1):100-108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimotsu S, Roehrl A, McCarty M, et al. Increased likelihood of missed appointments (“no shows”) for racial/ethnic minorities in a safety net health system. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):38-40. doi: 10.1177/2150131915599980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685-1687. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0747-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nwabuo CC, Dy SM, Weeks K, Young JH. Factors associated with appointment non-adherence among African-Americans with severe, poorly controlled hypertension. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazi DS, Wei PC, Penko J, et al. Scaling up pharmacist-led blood pressure control programs in Black barbershops: projected population health impact and value. Circulation. 2021;143(24):2406-2408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryant KB, Moran AE, Kazi DS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension treatment by pharmacists in Black barbershops. Circulation. 2021;143(24):2384-2394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakanishi M, Mizuno T, Mizokami F, et al. Impact of pharmacist intervention for blood pressure control in patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(1):114-120. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omboni S, McManus RJ, Bosworth HB, et al. Evidence and recommendations on the use of telemedicine for the management of arterial hypertension: an international expert position paper. Hypertension. 2020;76(5):1368-1383. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bosworth HB, Dudley T, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):e9-e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heisler M, Hogan MM, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, Pladevall M, Kerr EA. When more is not better: treatment intensification among hypertensive patients with poor medication adherence. Circulation. 2008;117(22):2884-2892. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Blood Pressure Control and Health Care Processes by Clinic

eTable 2. Process Measurements for Treatment Intensification (TI), Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Likelihood of Blood Pressure Control (<140/90 mm Hg) at the Last Visit During the Observation Period After Adjusting for Race

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension (HTN) Within a Network of Safety-Net Clinics in San Francisco, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 5. Racial Differences in Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) and Potential Mediators of BP Control Among Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension at Baseline, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension (HTN) Within a Network of Safety-Net Clinics in San Francisco, Excluding Patients Whose Blood Pressure (BP) Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eTable 7. Racial Differences in Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) and Potential Mediators of BP Control Among Patients With Hypertension at Baseline, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eTable 8. Likelihood of Blood Pressure Control (<140/90 mm Hg) by Race at the Last Visit During the Observation Period, Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eTable 9. Likelihood of Blood Pressure (BP) Control (<140/90 mm Hg) by Race at the Last Visit During the Observation Period, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eFigure 1. Racial Distribution by Clinic

eFigure 2. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black and Asian Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits Excluding Patients Seen at Least Twice in Cardiology or Nephrology Clinics Between January 2015 and November 2017

eFigure 3. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black and Asian Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits, Excluding Patients Whose BP Normalized Without Any Treatment Intensification

eFigure 4. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black Race With Blood Pressure (BP) Control Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits, Excluding Asian Patients

eFigure 5. Path Diagram and Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Association of Black Race With Change in Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) Mediated by Treatment Intensification, Follow-up Interval, and Missed Visits