Key Points

Question

What is the association of surgeon and patient sex concordance with postoperative outcomes?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 1 320 108 patients treated by 2937 surgeons, sex discordance between surgeon and patient was associated with a small but statistically significant increased likelihood of adverse postoperative outcomes. This was driven by worse outcomes for female patients treated by male physicians without a corresponding association among male patients treated by female physicians.

Meaning

This study found that sex discordance between surgeons and patients (particularly male surgeons and female patients) may contribute to worse surgical outcomes.

This cohort study examines the association between surgeon-patient sex discordance and postoperative outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Surgeon sex is associated with differential postoperative outcomes, though the mechanism remains unclear. Sex concordance of surgeons and patients may represent a potential mechanism, given prior associations with physician-patient relationships.

Objective

To examine the association between surgeon-patient sex discordance and postoperative outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this population-based, retrospective cohort study, adult patients 18 years and older undergoing one of 21 common elective or emergent surgical procedures in Ontario, Canada, from 2007 to 2019 were analyzed. Data were analyzed from November 2020 to March 2021.

Exposures

Surgeon-patient sex concordance (male surgeon with male patient, female surgeon with female patient) or discordance (male surgeon with female patient, female surgeon with male patient), operationalized as a binary (discordant vs concordant) and 4-level categorical variable.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Adverse postoperative outcome, defined as death, readmission, or complication within 30-day following surgery. Secondary outcomes assessed each of these metrics individually. Generalized estimating equations with clustering at the level of the surgical procedure were used to account for differences between procedures, and subgroup analyses were performed according to procedure, patient, surgeon, and hospital characteristics.

Results

Among 1 320 108 patients treated by 2937 surgeons, 602 560 patients were sex concordant with their surgeon (male surgeon with male patient, 509 634; female surgeon with female patient, 92 926) while 717 548 were sex discordant (male surgeon with female patient, 667 279; female surgeon with male patient, 50 269). A total of 189 390 patients (14.9%) experienced 1 or more adverse postoperative outcomes. Sex discordance between surgeon and patient was associated with a significant increased likelihood of composite adverse postoperative outcomes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09), as well as death (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13), and complications (aOR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11) but not readmission (aOR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.98-1.07). While associations were consistent across most subgroups, patient sex significantly modified this association, with worse outcomes for female patients treated by male surgeons (compared with female patients treated by female surgeons: aOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10-1.20) but not male patients treated by female surgeons (compared with male patients treated by male surgeons: aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.95-1.03) (P for interaction = .004).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, sex discordance between surgeons and patients negatively affected outcomes following common procedures. Subgroup analyses demonstrate that this is driven by worse outcomes among female patients treated by male surgeons. Further work should seek to understand the underlying mechanism.

Introduction

Surgical outcomes reflect a combination of preoperative decision-making, technical proficiency, and early identification and rescue of postoperative adverse events, which are highly integrated with clinical knowledge, communication skills, and clinical judgment.1 Patients treated by female surgeons may have better postoperative outcomes than those treated by male surgeons,2 although the mechanism has yet to be elucidated.

In primary care, sex or gender discordance between patients and physicians (particularly among male physicians and female patients) is associated with worse rapport, lower certainty of diagnosis, lower likelihood of assessing patient’s conditions as being of high severity, concerns of a hidden agenda,3 and disagreements regarding advice provided.4 These negative effects on interpersonal interactions have been shown to adversely affect process measures, such as adherence to preventive care protocols (eg, cancer screening5), and clinical outcomes, such as mortality following myocardial infarction.6

We postulated that sex discordance between surgeons and patients may contribute to differences in postoperative outcomes, with worse outcomes in female patients treated by male surgeons. To test this hypothesis, we performed a population-based, retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing common surgical procedures in Ontario, Canada, assessing the association between surgeon-patient sex discordance and 30-day postoperative outcomes, including death, complications, and readmissions.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of adults undergoing common procedures in Ontario, Canada, between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2019. Eligible Ontario residents receive insurance for physician and hospital services through a single government payer, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. We included patients who underwent 1 of 21 common elective and emergent procedures, including coronary artery bypass grafting, femoral-popliteal bypass, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, gastric bypass, colon resection, liver resection, spinal surgery (decompression and arthrodesis), craniotomy, knee replacement, hip replacement, open repair of the femoral neck, total thyroidectomy, neck dissection, lung resection, radical cystectomy, and carpal tunnel release, performed across a variety of subspecialties to ensure generalizability, including both open and laparoscopic approaches, when relevant.2 Multidisciplinary consultation was used for procedure selection. Unlike prior analyses of this cohort,2,7 we excluded sex-specific procedures to ensure sex-concordant and sex-discordant dyads were possible for all procedures. This study was reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline8 and the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) statement.9 The Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board approved this study. Based on the administrative nature of data used, individual patient consent was waived.

Data Sources

Using unique, patient-specific encrypted identifiers (Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences [ICES] key number), we linked the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, which tracks claims paid for physician billings, laboratories, and out-of-province clinicians10; the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), which contains records for hospitalizations11; the CIHI National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, which contains records for emergency department visits; the Registered Persons Database for demographic information12; and the Corporate Provider Database for surgeon-level data.

Cohort Derivation

We identified patients who underwent 1 of the 21 index procedures during the study interval (n = 1 870 221). We limited this to the first procedure for each patient (n = 1 459 600) and excluded patients treated by physicians whose primary declared specialty was nonsurgical (n = 6197), patients younger than 18 years (n = 40 290), those who were not Ontario residents (n = 432), those where the date of death preceded the date of surgery (n = 411), and those for whom we could not reliably link to DAD data to allow for assignment of treating institution (n = 70 766). Finally, we excluded patients with multiple surgical procedures on the same day (n = 18 752) and those with unreliable combinations of surgical specialty and procedure (eg, urology and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair; n = 2644), as these represent uncommon situations or miscoding and thus would diminish the generalizability of results. The overall study cohort included 1 320 108 unique patients.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was a composite adverse postoperative outcome, defined as death, readmission, or complication within 30 days after surgery.13 We used a previously used definition of surgical complications representing major morbidity, including reoperation.13 Outcomes were ascertained from health administrative data using a combination of uniformly collected procedural and diagnostic codes for all hospitals and patients in Ontario.13,14 Our secondary outcomes were individual components of the composite outcome and hospital length of stay.

Exposure

On an a priori basis, we assessed patient and surgeon sex concordance in 2 ways. First, we considered a binary variable indicative of sex discordance or concordance. Second, we considered a multilevel categorical variable with the 4 permutations of patient and surgeon sex: male surgeon and male patient, male surgeon and female patient, female surgeon and male patient, and female surgeon and female patient.

Covariates

Patient age, sex, geographic location (local health integration network15), geographically derived socioeconomic status, rurality, and general comorbidity (Johns Hopkins aggregate disease group16) were obtained. We also collected data regarding surgeon sex, years in practice, specialty, and surgical volume. Surgical volume was determined for each surgeon and the specific procedure by identifying the number of identical procedures the operating surgeon performed in the previous year, operationalized in quartiles. Hospital institution identifiers were used to account for facility-level variability.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the characteristics of patients, surgeons, and hospitals by patient-surgeon dyad sex concordance groups using Wilcoxon and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical data, respectively. We used multivariable generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an independent correlation structure and logit link to estimate the association between patient-surgeon sex concordance and outcomes, accounting for patient-, surgeon- and hospital-level covariates (as listed above), while clustering on the specific procedure performed. For analyses using the binary discordant variable, patient and surgeon sex were included in the models. To examine the association between patient-surgeon sex discordance and length of stay, a similar approach was conducted using Poisson regression. The unit of analysis was the patient.

We performed subgroup analyses to assess for an interaction between procedure, patient, surgeon, and hospital characteristics and the association between surgeon-patient sex concordance and outcomes. Based on the a priori hypothesis that outcomes may be worse for female patients treated by male surgeons, we examined for effect modification by patient sex. In terms of procedural characteristics, we performed preplanned stratified analysis based on elective or emergent procedures (classified using the CIHI-DAD database admission variables) and by case complexity (low vs high complexity; eTable 1 in the Supplement). We considered all same-day or outpatient surgery procedures to be elective. Finally, we considered era of surgery (2007 to 2012 vs 2013 to 2019).

Statistical significance was set at P < .05 based on a 2-tailed comparison. All analyses were performed using Enterprise Guide version 6.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

Among 1 320 108 patients treated by 2937 surgeons, 602 560 were sex concordant with their surgeon (509 634 male surgeon with male patient and 92 926 female surgeon with female patient) while 717 548 were sex discordant (667 279 male surgeon with female patient and 50 269 female surgeon with male patient). Baseline characteristics of the 4 groups are provided in Table 1; female surgeons in both relevant dyads were younger and had lower annual surgical volumes than male surgeons. Similarly, female surgeons treated younger patients with less comorbidity than male surgeons. Overall, 189 390 patients (14.9%) experienced an adverse postoperative outcome: 22 931 (1.7%) died, 88 132 (6.7%) were readmitted, and 114 421 (8.7%) had significant complications in the 30-day following surgery.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Cohort Stratified by Surgeon and Patient Sex.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant surgeon and patient | Discordant surgeon and patient | Total | ||||

| Male surgeon with male patient | Female surgeon with female patient | Male surgeon with female patient | Female surgeon with male patient | |||

| Patients, No. | 509 634 | 92 926 | 667 279 | 50 269 | 1 320 108 | NA |

| Surgeon characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (9.6) | 43.9 (8.1) | 49.0 (9.6) | 43.7 (8.2) | 48.4 (9.6) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 48 (41-56) | 43 (37-49) | 48 (41-56) | 42 (37-49) | 48 (41-55) | <.001 |

| Time in practice, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.9 (9.0) | 10.7 (8.1) | 14.8 (8.9) | 10.5 (8.6) | 14.4 (9.0) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (7-22) | 9 (4-17) | 15 (7-22) | 8 (3-17) | 15 (6-22) | <.001 |

| Surgical volume (quartiles) | ||||||

| 1 (Lowest) | 94 874 (18.6) | 24 551 (26.4) | 101 116 (15.2) | 15 584 (31.0) | 236 125 (17.9) | <.001 |

| 2 | 118 391 (23.2) | 30 572 (32.9) | 181 389 (27.2) | 13 996 (27.8) | 344 348 (26.1) | |

| 3 | 116 939 (22.9) | 23 670 (25.5) | 195 199 (29.3) | 9725 (19.3) | 345 533 (26.2) | |

| 4 (Highest) | 179 430 (35.2) | 14 133 (15.2) | 189 575 (28.4) | 10 964 (21.8) | 394 102 (29.9) | |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Cardiothoracic surgery | 71 026 (13.9) | 1854 (2.0) | 19 089 (2.9) | 6143 (12.2) | 98 112 (7.4) | <.001 |

| General surgery | 174 069 (34.2) | 64 304 (69.2) | 285 859 (42.8) | 30 756 (61.2) | 554 988 (42.0) | |

| Neurosurgery | 35 479 (7.0) | 1986 (2.1) | 29 497 (4.4) | 1683 (3.3) | 68 645 (5.2) | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 189 298 (37.1) | 14 636 (15.8) | 282 752 (42.4) | 6574 (13.1) | 493 260 (37.4) | |

| Otolaryngology | 11 715 (2.3) | 2974 (3.2) | 16 563 (2.5) | 1179 (2.3) | 32 431 (2.5) | |

| Plastic surgery | 13 920 (2.7) | 6005 (6.5) | 22 502 (3.4) | 2982 (5.9) | 45 409 (3.4) | |

| Thoracic surgery | 7470 (1.5) | 1097 (1.2) | 8875 (1.3) | 795 (1.6) | 18 237 (1.4) | |

| Urology | 1630 (0.3) | 30 (0.0) | 589 (0.1) | 21 (0.0) | 2270 (0.2) | |

| Vascular surgery | 5027 (1.0) | 40 (0.0) | 1553 (0.2) | 136 (0.3) | 6756 (0.5) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.2 (15.9) | 52.9 (18.1) | 59.8 (18.3) | 56.6 (17.5) | 59.7 (17.5) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 63 (52-73) | 53 (39-66) | 61 (47-74) | 59 (45-70) | 62 (48-73) | <.001 |

| Comorbidity, ADG score | ||||||

| 0-5 | 162 722 (31.9) | 22 273 (24.0) | 160 303 (24.0) | 17 866 (35.5) | 363 164 (27.5) | <.001 |

| 6-7 | 121 580 (23.9) | 22 174 (23.9) | 155 927 (23.4) | 11 704 (23.3) | 311 385 (23.6) | |

| 8-10 | 137 951 (27.1) | 29 726 (32.0) | 207 023 (31.0) | 12 853 (25.6) | 387 553 (29.4) | |

| ≥11 | 87 381 (17.1) | 18 753 (20.2) | 144 026 (21.6) | 7846 (15.6) | 258 006 (19.5) | |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Urban | 428 958 (84.2) | 81 273 (87.5) | 571 451 (85.6) | 43 250 (86.0) | 1 124 932 (85.2) | <.001 |

| Rural | 80 676 (15.8) | 11 653 (12.5) | 95 828 (14.4) | 7019 (14.0) | 195 176 (14.8) | |

| Income quintile | ||||||

| 1 (Lowest) | 92 881 (18.2) | 18 680 (20.1) | 137 800 (20.7) | 9417 (18.7) | 258 778 (19.6) | <.001 |

| 2 | 100 667 (19.8) | 18 955 (20.4) | 138 398 (20.7) | 9967 (19.8) | 267 987 (20.3) | |

| 3 | 102 689 (20.1) | 18 543 (20.0) | 134 110 (20.1) | 10 020 (19.9) | 265 362 (20.1) | |

| 4 | 105 899 (20.8) | 18 635 (20.1) | 132 060 (19.8) | 10 376 (20.6) | 266 970 (20.2) | |

| 5 (Highest) | 107 498 (21.1) | 18 113 (19.5) | 124 911 (18.7) | 10 489 (20.9) | 261 011 (19.8) | |

| Practice setting | ||||||

| Community hospital | 305 584 (60.0) | 61 967 (66.7) | 458 495 (68.7) | 28 758 (57.2) | 854 804 (64.8) | <.001 |

| Academic hospital | 204 050 (40.0) | 30 959 (33.3) | 208 784 (31.3) | 21 511 (42.8) | 465 304 (35.2) | |

| Year of index surgery | ||||||

| 2007 | 43 526 (8.5) | 5662 (6.1) | 58 217 (8.7) | 3272 (6.5) | 110 677 (8.4) | <.001 |

| 2008 | 41 202 (8.1) | 5714 (6.1) | 54 471 (8.2) | 3150 (6.3) | 104 537 (7.9) | |

| 2009 | 39 735 (7.8) | 5978 (6.4) | 53 674 (8.0) | 3242 (6.4) | 102 629 (7.8) | |

| 2010 | 38 628 (7.6) | 6164 (6.6) | 51 813 (7.8) | 3173 (6.3) | 99 778 (7.6) | |

| 2011 | 38 562 (7.6) | 6075 (6.5) | 51 760 (7.8) | 3326 (6.6) | 99 723 (7.6) | |

| 2012 | 38 117 (7.5) | 6668 (7.2) | 50 995 (7.6) | 3354 (6.7) | 99 134 (7.5) | |

| 2013 | 38 807 (7.6) | 6995 (7.5) | 51 889 (7.8) | 3699 (7.4) | 101 390 (7.7) | |

| 2014 | 38 409 (7.5) | 7434 (8.0) | 50 178 (7.5) | 3728 (7.4) | 99 749 (7.6) | |

| 2015 | 38 341 (7.5) | 7944 (8.5) | 49 740 (7.5) | 4287 (8.5) | 100 312 (7.6) | |

| 2016 | 38 723 (7.6) | 8125 (8.7) | 49 507 (7.4) | 4512 (9.0) | 100 867 (7.6) | |

| 2017 | 38 438 (7.5) | 8430 (9.1) | 48 298 (7.2) | 4532 (9.0) | 99 698 (7.6) | |

| 2018 | 38 639 (7.6) | 8743 (9.4) | 48 858 (7.3) | 4833 (9.6) | 101 073 (7.7) | |

| 2019 | 38 507 (7.6) | 8994 (9.7) | 47 879 (7.2) | 5161 (10.3) | 100 541 (7.6) | |

Abbreviation: ADG, aggregate disease group.

We first considered the association of surgeon-patient sex discordance while accounting for both patient and surgeon sex independently as well as other procedure-, patient-, surgeon-, and hospital-level factors. Sex discordance between the operating surgeon and the patient was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of a composite adverse postoperative outcome (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09). Sex discordance was further associated with increased likelihood of each secondary outcome; this was significant for death (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13) and complications (aOR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11) but not for readmission (aOR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.98-1.07) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Sex discordance was also associated with longer length of stay (adjusted relative rate, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15).

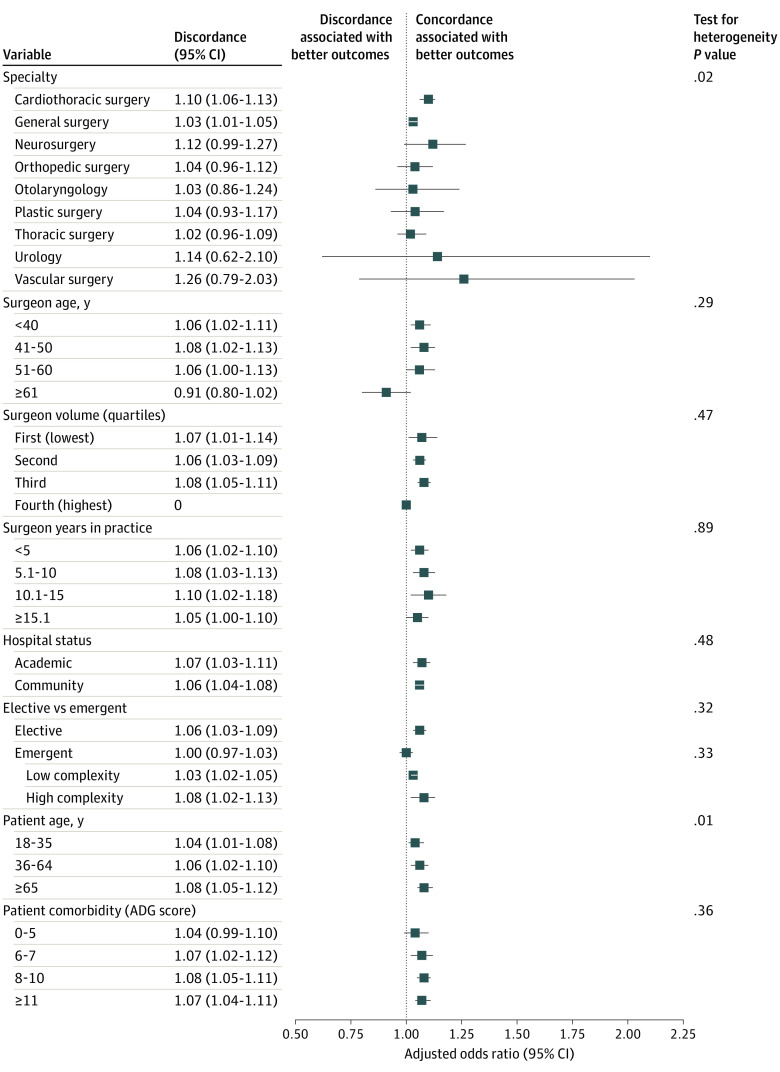

In stratified analyses according to surgeon, patient, procedural, and hospital characteristics while assessing the primary composite adverse postoperative outcome, we found significant heterogeneity in the association of sex discordance with development of adverse postoperative outcomes by patient sex: sex discordance was associated with worse outcomes for female patients (aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06-1.16) but better outcomes for male patients (aOR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.93-0.99) (P for interaction = .004). Among other subgroups, while statistical power was diminished and some of the confidence intervals crossed 1, all but 1 (patients treated by surgeons 61 years and older) demonstrated an increased likelihood of adverse postoperative outcomes for patients who are sex discordant with their surgeons (Figure 1). There was significant heterogeneity between surgical specialties; however, the effect estimate indicated that sex discordance was associated with higher event rates for all specialties. There was further significant heterogeneity according to patient age, with an increasing magnitude of the association of sex discordance with increasing patient age. While there was no significant heterogeneity of effect between elective and emergent surgery, the effect estimate was null for those undergoing emergent surgery (aOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.97-1.03; P for interaction = .32). We found no change in the association of sex discordance whether patients were treated early in the cohort accrual (2007 to 2012; aOR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.08) or later (2013 to 2019; aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11) (P for interaction = .87).

Figure 1. Likelihood of Adverse Postoperative Outcomes (Death, Readmission, and Complications) According to Surgeon and Patient Sex Concordance, Stratified by Physician, Patient, Hospital, and Procedural Factors.

ADG indicates aggregate disease group.

Second, on an a priori basis and supported by the evidence of effect modification according to patient sex described above, we examined adjusted absolute rates of each of outcome across 4 categories of surgeon-patient sex concordance and discordance, stratified by surgical subspecialty and adjusted for relevant patient-, physician-, and hospital-level variables while clustering on procedure type. While male patients consistently had higher rates of postoperative events (eFigure in the Supplement), there were relatively small differences in rates of composite adverse postoperative outcomes among male patients treated by male and female surgeons (range in difference between male and female surgeons, 0.1% to 0.4% among specialties), while female patients treated by male surgeons had consistently higher adjusted rates of postoperative events compared with those treated by female surgeons (range in difference between male and female surgeons, 0.6% to 2.5% among specialties) (Table 2).

Table 2. Adjusted Rates of Postoperative Outcomes Stratified to Examine the Interaction Between Surgeon and Patient Sex on Postoperative Outcomes, by Surgeon Specialtya.

| Surgeon-patient sex pair | % | Length of stay, mean, d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite end point | Death | Readmissions | Complications | ||

| General surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 23.5 | 0.9 | 10.1 | 15.4 | 3.8 |

| Female patient | 18.0 | 0.6 | 8.1 | 11.2 | 3.3 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 23.1 | 0.8 | 9.6 | 15.5 | 3.8 |

| Female patient | 16.0 | 0.5 | 7.3 | 9.8 | 2.7 |

| Cardiothoracic surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 26.4 | 1.9 | 13.5 | 15.5 | 9.3 |

| Female patient | 20.2 | 1.4 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 8.3 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 26.0 | 1.6 | 12.8 | 15.6 | 9.4 |

| Female patient | 18.0 | 1.0 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 6.8 |

| Neurosurgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 17.0 | 1.6 | 11.2 | 7.4 | 6.0 |

| Female patient | 13.0 | 1.2 | 9.0 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 16.8 | 1.4 | 10.6 | 7.4 | 6.1 |

| Female patient | 11.6 | 0.9 | 8.1 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Orthopedic surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 10.3 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Female patient | 7.9 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 10.2 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Female patient | 7.0 | 0.4 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| Otolaryngology | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 13.4 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 4.1 |

| Female patient | 10.3 | 0.3 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 3.6 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 13.3 | 0.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 4.1 |

| Female patient | 9.2 | 0.2 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.0 |

| Plastic surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 7.4 | 0.1 | 7.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Female patient | 5.6 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 7.2 | 0.1 | 7.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Female patient | 5.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Thoracic surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 17.1 | 0.8 | 10.8 | 8.4 | 4.5 |

| Female patient | 13.0 | 0.6 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 4.0 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 16.8 | 0.7 | 10.3 | 8.4 | 4.5 |

| Female patient | 11.6 | 0.4 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 3.3 |

| Urology | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 30.6 | 0.8 | 22.1 | 15.0 | 6.1 |

| Female patient | 23.4 | 0.6 | 17.6 | 10.9 | 5.4 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 30.1 | 0.7 | 20.9 | 15.1 | 6.1 |

| Female patient | 20.9 | 0.4 | 16.0 | 9.5 | 4.4 |

| Vascular surgery | |||||

| Male physician | |||||

| Male patient | 25.5 | 1.7 | 9.8 | 17.1 | 5.2 |

| Female patient | 19.5 | 1.2 | 7.8 | 12.4 | 4.6 |

| Female physician | |||||

| Male patient | 25.1 | 1.5 | 9.3 | 17.2 | 5.3 |

| Female patient | 17.4 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 3.8 |

Adjusted absolute rates derived from using Poisson generalized estimating equation model dealing with clustering based on procedure fee code, adjusted for surgeon volume, surgeon specialty, surgeon age, patient age, comorbidity, rurality, income quintile, and hospital setting. The rates were estimated using surgeon volume (quartile 3), surgeon age (median age), patient age (median age), comorbidity (aggregate disease group score of 8 to 10), rurality (urban), income quintile (quintile 3), and hospital setting (academic) for each surgeon specialty.

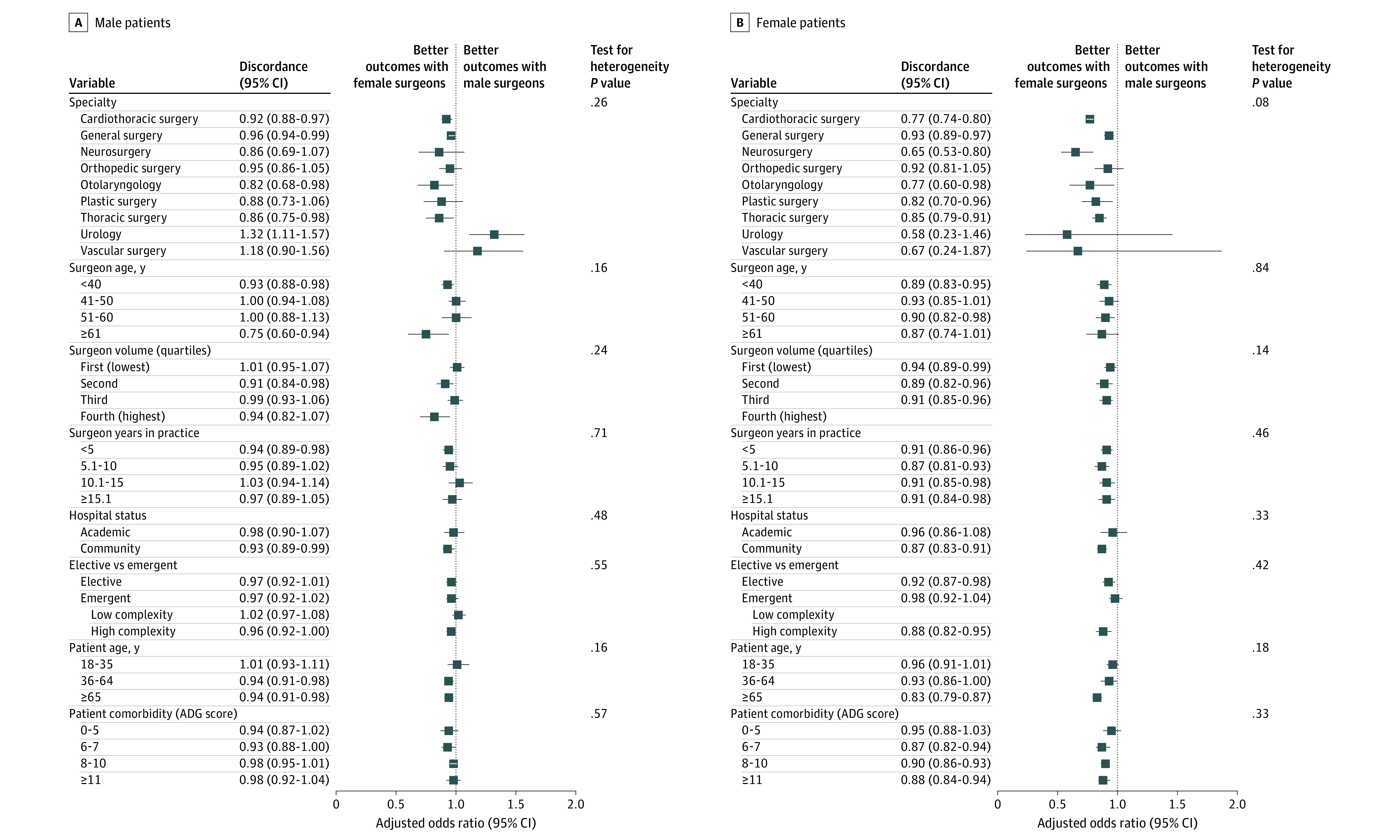

We then performed multivariable modeling using this 4-level variable operationalization of patient-surgeon sex discordance: male surgeons with male patients, male surgeons with female patients, female surgeons with male patients, and female surgeons with female patients. As patient sex was a significant independent predictor of outcomes in all models, we examined these outcomes stratified by patient sex. The association of sex discordance was limited to female patients treated by male surgeons compared with female patients treated by female surgeons (composite end point: aOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10-1.20) and was not found among male patients treated by female surgeons compared with male patients treated by male surgeons (composite end point: aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.95-1.03) (P for interaction = .004). A similar pattern emerged for each end point: outcomes for discordant female surgeon/male patient dyads were comparable or better than those of the male surgeon/male patient dyads, while discordant male surgeon/female patient dyads had consistently statistically significantly worse outcomes than female surgeon/female patient dyads (Table 3). As with the first binary operationalization of sex discordance, we performed stratified subgroup analyses according to surgeon, patient, procedural, and hospital, again with the cohort stratified according to patient sex. Within each group, we examined the association between male and female surgeons and the primary composite adverse postoperative outcome, for each subgroup. While we found consistent evidence of comparable or somewhat better outcomes for male patients treated by female surgeons, this association was significantly larger for female patients and consistent across subgroups (Figure 2).

Table 3. Stratified Analysis According to Patient Sex to Examine the Association of Patient and Surgeon Sex Concordance on Adverse Postoperative Outcomes, Using Multivariable Generalized Estimating Equation Regression Models, With Clustering Based on Procedure Fee Code.

| Surgeon-patient sex pair | aOR (95% CI)a | Length of stay, aRR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite end point | Death | Readmissions | Complications | ||

| Among male patients | |||||

| Male physician (concordant) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female physician (discordant) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | 0.94 (0.88-1.00) | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) |

| Among female patients | |||||

| Female physician (concordant) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Male physician (discordant) | 1.15 (1.10-1.20) | 1.32 (1.14-1.54) | 1.11 (1.04-1.19) | 1.16 (1.11-1.22) | 1.20 (1.11-1.30) |

| P value for test for heterogeneity | .004 | .003 | .01 | .02 | .01 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratios; aRR, adjusted relative rates.

Models adjusted for physician age, years in practice, surgical volume, surgical subspecialty, patient age, patient comorbidity, patient income quintile, region of residency, rurality, hospital designation, and year of surgery.

Figure 2. Likelihood of Adverse Postoperative Outcomes (Death, Readmission, and Complications) According to Surgeon Sex, Stratified by Physician, Patient, Hospital, and Procedural Factors Among Male and Female Patients.

ADG indicates aggregate disease group.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort, we found consistent evidence that adverse postoperative outcomes, defined as the composite of death, readmission, or complications in the 30 days following surgery, were significantly more common when there was a discordance between surgeon and patient sex after accounting for both patient and surgeon sex as well as the specific procedure being performed and other procedure-, patient-, surgeon-, and hospital-level factors, although the absolute magnitude of this association was relatively small. This association was robust to subgroup analyses assessing procedure-, patient-, physician-, and hospital-level characteristics. However, it varied significantly based on patient sex; while sex discordance was associated with worse outcomes for female patients (aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06-1.16), it was associated with better outcomes for male patients (aOR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.93-0.99). Further analyses support that worse outcomes among female patients treated by male surgeons drives the observed association of sex discordance.

To our knowledge, this represents the first analysis assessing the association of surgeon and patient sex concordance with surgical outcomes. While a number of other studies have examined the association of sex discordance with process measures (with somewhat inconsistent results),3,4,5,17,18,19 only one other study we are aware of has examined the association of sex discordance on clinical outcomes.6 Among patients admitted to Florida hospitals for myocardial infarction, Greenwood and colleagues6 demonstrated that female patients treated by male physicians had higher morality, although mortality was similar for both men and women treated by female physicians. Notably, these authors demonstrated lower mortality in female patients regardless of treating physician sex, in parallel to our findings.

Understanding the causes underlying these observations offers the potential to improve the care for all patients. While predominantly assessed in the primary care setting, available literature suggests that sex or gender discordance may adversely affect the physician-patient relationship and interaction,3,4 in a particularly negative manner for female patients and male physicians. These data, combined with prior observations regarding disparities in cardiac care20 and pain treatment,21 suggest an underappreciation for the severity of symptoms in female patients, particularly among male physicians. However, work has also shown that patients may report less postoperative pain to male assessors.22 In addition to a patient preference for sex concordance of their surgeon in situations of sensitive examinations,23 sex discordance may lead to incomplete examinations in the postoperative setting. These issues may contribute to a failure to rescue when patients have minor deviations from expected postoperative pathways.24 Failure to appropriately identify and intervene when these deviations are minor leads to higher rates of serious adverse postoperative outcomes.25,26 Ongoing work is aimed at quantitatively assessing whether this underpins the observed association but is beyond the scope of this article. Potentially important unmeasured patient and physician sociocultural factors, unconscious bias, and communication styles that may contribute meaningfully to differences in surgeon-patient interactions are unable to be captured in the administrative data sets, as used in this analysis.

In parallel to the effect of gender or sex concordance, recent work has demonstrated the importance of racial concordance between patients and physicians on clinical outcomes.27 Higher Press Gainey scores among racially concordant pairs suggest that a better patient-physician relationship may drive this observation.28 Further, work has shown that the patient-physician relationship is strengthened by a shared identity, which may be driven by sex, race and ethnicity, or other personal beliefs and values.29 However, physician’s use of patient-centered communication may mitigate differences due to sex or race.29

In this cohort, patient sex was significantly associated with postoperative morbidity and mortality, despite accounting for other procedure-, patient-, surgeon-, and hospital-level factors. This is consistent with multiple prior analyses among patients undergoing surgery in Ontario2,7 as well as other comparative analyses of mortality between men and women.30

Limitations and Strengths

Owing to the observational nature of this study, there are limitations. First, we captured biologic sex and are unable to assess gender, which may more meaningfully affect interpersonal interactions. Second, while we specifically accounted for the procedure performed (as defined by billing codes) in our GEE, as granular metrics of case complexity were not available, it is possible that, within each procedure examined, male surgeons may perform more complex or high-risk cases. This would contribute to unmeasured confounding. However, a stratified analysis by case complexity did not show heterogeneity of effect, and there is not an underlying rationale to support that male surgeons are more likely to perform a more complex subset of each procedure. Third, we are unable to account for the potential influence of residents, nurses, and other physicians apart from the primary billing surgeon of record on patients’ outcomes. This represents a valuable avenue of future work to understand how these additional members of the health care team may either strengthen or impair the patient-surgeon relationship. We noted a consistent association of sex discordance across academic and community hospitals, suggesting that resident teams are unlikely to dissipate this effect. Fourth, newer technologies, such as robotic-assisted surgery, were not widely disseminated in Ontario during the study interval and were thus excluded. However, there is not strong underlying rationale to suspect that the association of surgeon-patient sex discordance with outcomes would be meaningfully affected by advances in surgical technology. Fifth, in addition to GEE models (clustered on procedure), we attempted hierarchical modeling for this data at 2 or more levels (eg, clustering by surgeon and institution), but these models could not be fitted because of computational constraints.

Nonetheless, this study has many strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to address the question of the association between surgeon-patient sex concordance and surgical outcomes and uses a large, generalizable population-based cohort. Second, because of the variety of surgical specialties and both elective and emergent procedures included, the results are generalizable across the spectrum of surgical practice. Third, the single-payer health care system in Ontario, Canada, provides generalizable results owing to the inclusion of almost all patients undergoing the selected surgical procedures. Fourth, the use of administrative data allows the comprehensive identification of readmissions or complications following surgery occurring anywhere in the province, whether at the initial hospital where the patient underwent surgery or elsewhere.

Conclusions

This large, population-based study demonstrates a small but significant increase in rates of adverse postoperative outcomes, defined as the composite of death, complications, or readmission in the 30 days following surgery when there is a sex discordance between surgeons and patients. This is driven by worse outcomes among female patients treated by male surgeons. These findings support examinations of surgical outcomes and mechanisms as they relate to physicians and the underlying process and patterns of care to improve outcomes for all patients. Further sociologic research to evaluate how sex concordance, among other factors, influences patient-physician relationships, communication, and trust are warranted.

eFigure. Association of patient sex with composite complication rates across included surgical procedures.

eTable 1. Definition of low- and high-complexity surgical procedures for subgroup analyses.

eTable 2. Result of multivariable generalized estimating equation regression models, with clustering based on procedure fee code, to examine the interaction between surgeon and patient sex discordance and postoperative outcomes.

References

- 1.Thomas WE. Teaching and assessing surgical competence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(5):429-432. doi: 10.1308/003588406X116927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallis CJ, Ravi B, Coburn N, Nam RK, Detsky AS, Satkunasivam R. Comparison of postoperative outcomes among patients treated by male and female surgeons: a population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross R, McNeill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P. The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians’ perceptions of their patients. Women Health. 2008;48(2):123-144. doi: 10.1080/03630240802313464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schieber AC, Delpierre C, Lepage B, et al. ; INTERMEDE group . Do gender differences affect the doctor-patient interaction during consultations in general practice? results from the INTERMEDE study. Fam Pract. 2014;31(6):706-713. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra J, Rotter D, Tsui J, Llanos AAM, Balasubramanian BA, Demissie K. Impact of patient-provider race, ethnicity, and gender concordance on cancer screening: findings from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(12):1804-1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(34):8569-8574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800097115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satkunasivam R, Klaassen Z, Ravi B, et al. Relation between surgeon age and postoperative outcomes: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2020;192(15):E385-E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee . The Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JI, Young W. A summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, Blackstien-Hirsch P, Fooks C, Naylor CD, eds. Patterns of Health Care in Ontario: The ICES Practice Atlas. Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences; 1996:339-345. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: A Validation Study. Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iron K, Zagorski BM, Sykora K, Manuel DG. Living and Dying in Ontario: An Opportunity for Improved Health Information. Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govindarajan A, Urbach DR, Kumar M, et al. Outcomes of daytime procedures performed by attending surgeons after night work. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):845-853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1415994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urbach DR, Govindarajan A, Saskin R, Wilton AS, Baxter NN. Introduction of surgical safety checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):1029-1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1308261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Home and Community Care Support Services . Homepage. Accessed April 16, 2021. http://www.lhins.on.ca/

- 16.The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health . The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Reference Manual Version 7.0. The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jerant A, Bertakis KD, Fenton JJ, Tancredi DJ, Franks P. Patient-provider sex and race/ethnicity concordance: a national study of healthcare and outcomes. Med Care. 2011;49(11):1012-1020. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31823688ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583-589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women. does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):478-482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nabel EG. Coronary heart disease in women—an ounce of prevention. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(8):572-574. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann DE, Tarzian AJ. The girl who cried pain: a bias against women in the treatment of pain. J Law Med Ethics. 2001;29(1):13-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2001.tb00037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer-Frießem CH, Szalaty P, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. A prospective study of patients’ pain intensity after cardiac surgery and a qualitative review: effects of examiners’ gender on patient reporting. Scand J Pain. 2019;19(1):39-51. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2018-0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groutz A, Amir H, Caspi R, Sharon E, Levy YA, Shimonov M. Do women prefer a female breast surgeon? Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0094-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lafonte M, Cai J, Lissauer ME. Failure to rescue in the surgical patient: a review. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25(6):706-711. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston M, Arora S, Anderson O, King D, Behar N, Darzi A. Escalation of care in surgery: a systematic risk assessment to prevent avoidable harm in hospitalized patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):831-838. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1368-1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21194-21200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913405117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198-205. doi: 10.1370/afm.821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu YT, Niubo AS, Daskalopoulou C, et al. Sex differences in mortality: results from a population-based study of 12 longitudinal cohorts. CMAJ. 2021;193(11):E361-E370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Association of patient sex with composite complication rates across included surgical procedures.

eTable 1. Definition of low- and high-complexity surgical procedures for subgroup analyses.

eTable 2. Result of multivariable generalized estimating equation regression models, with clustering based on procedure fee code, to examine the interaction between surgeon and patient sex discordance and postoperative outcomes.