Abstract

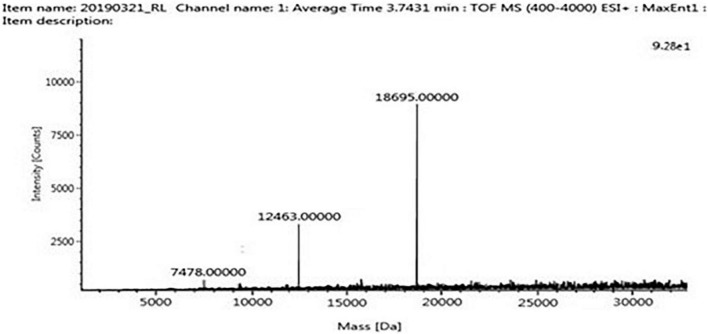

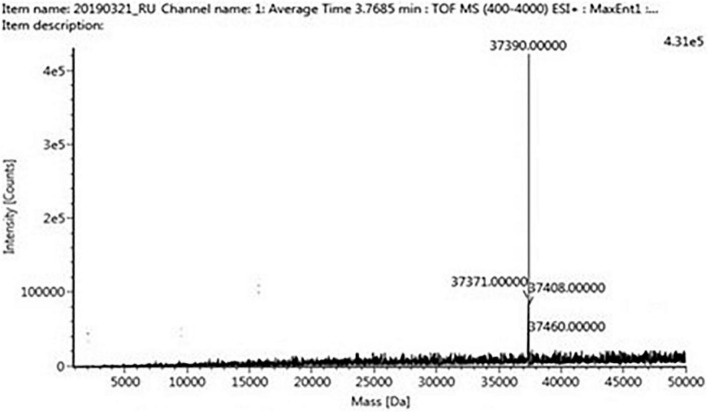

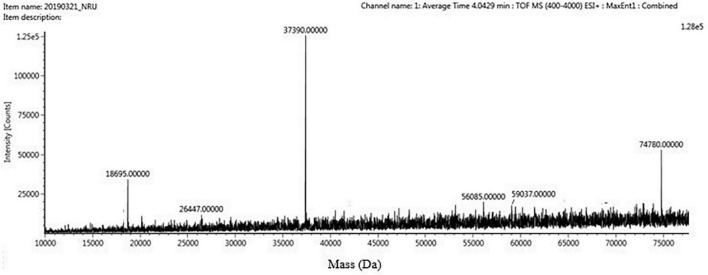

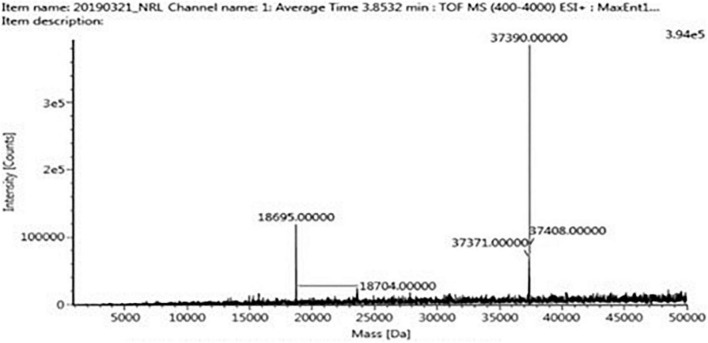

A Bowman-Birk protease, i.e., Mucuna pruriens trypsin inhibitor (MPTI), was purified from the seeds by 55.702-fold and revealed a single trypsin inhibitor on a zymogram with a specific activity of 202.31 TIU/mg of protein. On sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) under non-reducing conditions, the protease trypsin inhibitor fraction [i.e., trypsin inhibitor non-reducing (TINR)] exhibited molecular weights of 74 and 37 kDa, and under reducing conditions [i.e., trypsin inhibitor reducing (TIR)], 37 and 18 kDa. TINR-37 revealed protease inhibitor activity on native PAGE and 37 and 18 kDa protein bands on SDS–PAGE. TINR-74 showed peaks corresponding to 18.695, 37.39, 56.085, and 74.78 kDa on ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled with electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (ESI/QTOF-MS). Similarly, TINR-37 displayed 18.695 and 37.39 kDa peaks. Furthermore, TIR-37 and TIR-18 exhibited peaks corresponding to 37.39 and 18.695 kDa. Multiple peaks observed by the UPLC-ESI/QTOF analysis revealed the multimeric association, confirming the characteristic and functional features of Bowman-Birk inhibitors (BBIs). The multimeric association helps to achieve more stability, thus enhancing their functional efficiency. MPTI was found to be a competitive inhibitor which again suggested that it belongs to the BBI family of inhibitors, displayed an inhibitor constant of 1.3 × 10–6 M, and further demonstrates potent anti-inflammatory activity. The study provided a comprehensive basis for the identification of multimeric associates and their therapeutic potential, which could elaborate the stability and functional efficiency of the MPTI in the native state from M. pruriens.

Keywords: anti-inflammatory activity, multimeric association, Bowman-Birk inhibitor, seed proteins, Mucuna pruriens

Introduction

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are small proteins or peptides that inhibit the proteolytic activity of enzymes by forming high-affinity stoichiometric complexes (Bode and Huber, 2000). PIs are widely distributed in plants, animals, and microorganisms. Furthermore, they are mostly abundant in seeds and tubers of plants belonging to the Fabaceae, Solanaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Poaceae families (Connors et al., 2002). PIs have been grouped into various classes, depending on their inhibitory specificity, of which serine-type PIs (SPIs) are most comprehensively studied and characterized (Rawlings et al., 2018). Moreover, several types of SPIs have been extensively purified, characterized, and assessed for their biological potential from various sources (Clemente et al., 2019). In plants, these proteins are involved in many physiological processes, such as the regulation of endogenous and exogenous proteolysis, delaying senescence, and acting as defensive molecules, thereby protecting against pathogens (Pak and Van Doorn, 2005; Joshi et al., 2014; Yasin et al., 2014, 2020). Additionally, they are involved in signal transduction, mobilization of storage proteins, and morphogenesis during plant development (Yasin et al., 2014, 2020; Rustgi et al., 2017).

Recently, SPIs have garnered substantial attention for potential application in biomedicine and biotechnology. They act as efficient tools to control unwanted proteolysis and to treat conditions, such as AIDS, respiratory diseases, hypertension, cancer, microbial infections, and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, SPIs regulate blood coagulation, inflammation, signal cascade in the immune system and cell cycle. Therefore, SPIs can be the potent candidates for drug design and development (Fumagalli et al., 1996; Thompson and Palmer, 1998; Kato, 1999; Kataoka et al., 2002; Nyberg et al., 2006; Srikanth and Chen, 2016; Cristina Oliveira de Lima et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020). The Bowman-Birk inhibitor (BBI) family is a type of SPIs with the characteristic features of two reactive sites, independent and simultaneous inhibition of two serine proteases with different specificity, rigid compact structure, stability to extreme pH, and temperature conditions (Hellinger and Gruber, 2019). It is believed that dicot BBIs could have been evolved from a single-headed ancestral BBI via internal gene duplication, fusion, and mutation processes. This suggested that a higher molecular weight (MW) of 16 kDa BBIs might have been evolved from a small MW of 8 kDa BBIs (Song et al., 1999). This hypothesis gets credence by the presence of intramolecular sequence homology in BBIs. At present, the sequences of numerous BBIs from various plant sources are available at the plant PIs database accessible at the MEROPS database1 and the NCBI database.2 BBI has potential pharmaceutical properties and therapeutic applications (Hellinger and Gruber, 2019; Gitlin-Domagalska et al., 2020).

The association of SPIs in legumes is a natural, fundamental process. The appropriate association of the monomers to multimeric forms helps in the sustained/retained activity of the inhibitor in its native state. If the monomers do not associate and form the stable multimeric structure, the inhibitor is rendered inactive, thereby reducing its biological activity (Catalano et al., 2003). Reportedly, the BBI type commonly exhibits this kind of association (Arentoft et al., 1993; Prasad et al., 2010). Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS) is a high resolution, less elution time MS (in a column with a non-porous particle size below 2 mm) for proteins (Eschelbach and Jorgenson, 2006). Furthermore, UPLC is a pivotal tool for analyzing associated proteins in bulk coupled with good retention time, thereby more number of proteins with higher molecular mass can be efficiently observed (Everley and Croley, 2008). However, adequate information regarding the utilization of UPLC-based MS to identify the monomeric forms of BBIs is lacking. In this regard, we attempted to identify the association of monomeric forms of a BBI from Mucuna pruriens seeds through UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS.

The genus Mucuna of the Fabaceae family includes numerous plants of diverse habitats. M. pruriens is an underutilized forage and medicinal plant primarily used by tribal communities of India, China, and African countries for treating snakebites as an antagonist to the venom (Naja spp., Echis, Calloselasma, and Bungarus). In addition, the plant has shown potential in prophylactic treatment (Guerranti et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2009; Meenatchisundaram and Michael, 2010). M. pruriens seeds can be used to cure Parkinson’s disease and depressive neurosis (Katzenschlager et al., 2004). Recent studies on M. pruriens resulted in successful isolation and purification of various biological compounds such as carboxylesterase and amylase inhibitor (Chandrashekharaiah et al., 2011; Bharadwaj et al., 2018). SPIs are putative targets in pharmaceutics; however, their multimeric associations are yet to be characterized. In view of their contemporary importance, the present investigation was undertaken to study SPIs from a potential source, i.e., M. pruriens seeds. This study illustrates the purification and characterization of a BBI and the multimeric associations of its monomers by UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The M. pruriens seeds were collected from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Indian Institute of Horticultural Research Center, Bangalore, India.

Purification of Mucuna pruriens Trypsin Inhibitor

The M. pruriens seeds were soaked for 12 h at room temperature; the seed coats were removed; and a 10% butanol cake of the cotyledons was prepared (Wetter, 1957). The cake obtained was dried, powdered, and stored at 4°C until used. Furthermore, 10% crude “trypsin inhibitor” extract was prepared by stirring the powder in 0.1 N HCl on a magnetic stirrer at 4°C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation (Remi C-24 Plus, Vasai, India) at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatant was collected and subjected to 0–25%, 25–50%, and 50–90% ammonium sulfate fractionation (Bollag et al., 1996). Pellets obtained after fractionation were dissolved separately in sodium acetate buffer (0.025 mM; pH 5.7) and dialyzed for 1.3 h against the same buffer at 4°C. A fraction containing the 25–50% dialysate was loaded onto the carboxymethyl cellulose (CM)-cellulose column (2.3 × 7.5 cm) preequilibrated with sodium acetate buffer (0.025 mM; pH 5.7). The column was washed with start buffer (0.025 mM sodium acetate buffer; pH 5.7) at a flow rate of 60 ml/h with a fraction volume of 10 ml. Bound proteins were eluted stepwise using 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 M NaCl. The column-bound fraction exhibiting trypsin inhibitor activity was pooled and concentrated. Furthermore, the concentrated CM-cellulose fraction was subjected to Sephadex G-75 gel filtration chromatography (1.0 × 1.5 cm) preequilibrated with sodium acetate buffer (0.025 mM; pH 5.7). Fractions of 2 ml were collected at a flow rate of 10 ml/h. Fractions exhibiting trypsin inhibitor activity were pooled and concentrated using Centricon tubes (MilliporeMerck, Darmstadt, Germany) (MW cutoff of 5 kDa). The concentrated Sephadex G-75 fraction was further subjected to preparative gel electrophoresis as follows: 10% non-denaturing preparative cationic PAGE performed at pH 4.3 (10% T and 5% C) (Reisfeld et al., 1962). Following electrophoresis, a native zymogram was performed to identify bands containing trypsin inhibitor activity; such bands were sliced, transferred, and macerated in a glass homogenizer at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant obtained was stored for further analysis.

Protein Estimation

Total protein was determined as reported previously, using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard (Lowry et al., 1951). The protein content of all the CM-cellulose fractions was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer serine protease (SP 3000-Plus, Optima, Tokyo, Japan).

Trypsin Activity and Trypsin Inhibitory Activity

Trypsin activity assay was performed using N-Benzoyl-DL-arginine-4-nitroanilide hydrochloride (BAPNA) as the substrate (Shibata et al., 1986). Trypsin was dissolved in 0.001 N HCl containing 20 mM CaCl2 at a concentration of 200 μg/ml. BAPNA (200 mg) was dissolved in 3 ml dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the volume was made up to 100 ml with 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.2). The assay mixture (containing 500 μl trypsin, 500 μl 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.2, and 1.25 ml BAPNA) was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.4 ml of 30% acetic acid. The absorbance was read at 410 nm against reagent blank and converted to trypsin unit (TU; one TU increases optical density (OD) by 0.01 at 410 nm).

Trypsin inhibitory activity was measured as reported previously (Shibata et al., 1986). The assay mixture (500 μl trypsin, 400 μl 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.2, and 100 μl purified inhibitor) was incubated at 37°C for 15 min followed by the addition of 1.25 ml BAPNA and again incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.4 ml of 30% acetic acid. The absorbance was measured at 410 nm against reagent blank and converted to trypsin inhibitor unit (TIU; one TIU decreases OD by 0.01 at 410 nm).

Electrophoresis

Cationic native PAGE was performed with 10% T and 5% C as previously described (Reisfeld et al., 1962). After electrophoresis, the gel was stained for proteins with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (w/v) in 3.5% (w/v) perchloric acid for 1 h and washed several times with distilled water. The gel was destained with 25% methanol and 10% acetic acid solution.

The inhibitory activity was quantified by reverse zymography on gelatin-PAGE, wherein 1% gelatin was copolymerized with the polyacrylamide matrix (Felicioli et al., 1997). After electrophoresis, the gel was incubated with Tris–HCl buffer (0.1 M; pH 7.6) for 30 min, followed by trypsin treatment (100 μg/ml) for 30 min. The gel was washed with distilled water, stained, and destained as prescribed earlier (Felicioli et al., 1997). Colored bands appeared against a transparent background correspond to trypsin inhibition.

The SDS–PAGE was carried out using a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel (12.5% T and 5% C) with or without β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) (Laemmli, 1970). After the electrophoretic run, the gel was removed, stained, and destained as described earlier. The non-reducing band corresponding to 37 kDa (TINR-37) was sliced, transferred, and macerated in a glass homogenizer at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant obtained was subjected to native PAGE for both protein and inhibitor staining. The homogeneity of the purified trypsin inhibitor (TINR-37) was analyzed on the SDS–PAGE in the presence or absence of β-ME, as described earlier.

Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization/Quadrupole Time-of-Flight-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The SDS was removed from both non-reducing and reducing SDS–PAGE gels by treating them with Triton X-100. PI bands [i.e., M. pruriens trypsin inhibitor (MPTI)] corresponding to the MWs of 74 and 37 kDa from the non-reducing gel (i.e., TINR-74 and TINR-37) and that of 37 and 18 kDa from the reducing gel (i.e., TIR-37 and TIR-18) were sliced and transferred to a glass homogenizer separately. The gels were homogenized at 4°C with sodium acetate buffer (0.025 M; pH 5.7) with an equal volume of 1 M CaCl2 (Zhou et al., 2012). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected and filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter papers. The filtrates were analyzed using UPLC (Acquity UPLC, Waters Corporation, Milford, CT, United States) coupled with ESI/QTOF-MS (Synapt G2-Si, Waters Corporation, Milford, CT, United States). Separations were carried out using an ethylene-bridged hybrid C4 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) with 0.1% formic acid in double distilled water and acetonitrile as the mobile phase. All acquisitions were performed on positive polarity with the following ESI settings: capillary voltage = 3 kV, cone voltage = 40 V, source temperature = 120°C, desolvation gas = 350°C, and the instrument was tuned for protein analysis. The MS data were acquired with a mass range from 400 to 4,000 m/z on the UPLC-based ESI/QTOF-MS. The instrument was operating on a resolution of 40,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM). The charge state spectra were subject to deconvolution using the maximum entropy 1 algorithm on the UVIFI informatics platform (Wang et al., 2018).

Determination of km, Vmax, and Inhibitor Constant (ki)

The km and Vmax of trypsin for BAPNA in the presence of MPTI were determined from the Lineweaver–Burk plot; the inhibition constant (ki) was calculated from the plots (Lineweaver and Burk, 1934). The residual inhibitory activities were determined using BAPNA as a substrate, as described earlier.

Determination of Anti-inflammatory Activity Using the Hemolytic Assay

The hemolytic assay with slight modifications was performed (Mizushima and Kobayashi, 1968). Goat blood samples (20 ml at 0–4°C) were collected using anticoagulants from a slaughterhouse. The suspension solution of red blood cells (RBC) was prepared by centrifuging the blood sample at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, followed by three washes with 0.85% NaCl solution. The volume of the suspension was made up to 20 ml with isosaline. The assay mixture of 1 ml (100, 200, 300, and 400 μg) of MPTI with 2 ml hyposaline and 0.5 ml RBC suspension was incubated for 30 min and then centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and its absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a spectrophotometer. Control was prepared using hyposaline and the RBC suspension. Diclofenac (1 mg/ml) was used as the standard drug.

| (1) |

where A1 = absorption of control and A2 = absorption of test sample.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in replicates. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and Excel. The data shown are mean ± SE/SD. Results are expressed as graphs prepared using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., California, United States) and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Purification Analysis

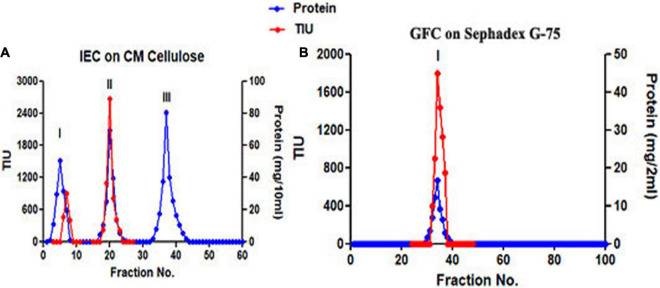

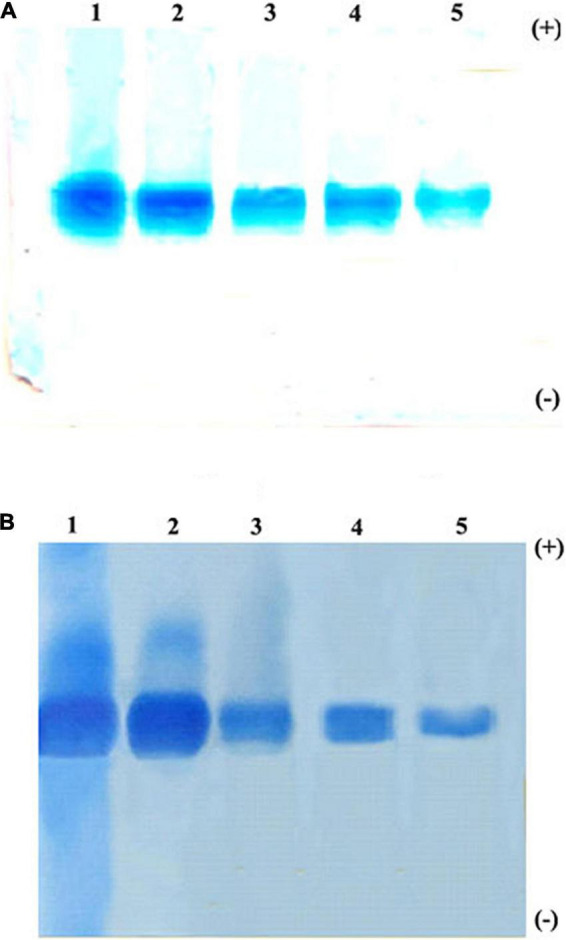

The trypsin-specific PI was purified to homogeneity from M. pruriens seeds using different conventional techniques such as acid extraction, salt fractionation, CM-cellulose chromatography, Sephadex G-75 gel filtration chromatography, and preparative gel electrophoresis. The purification results showing recovery, fold purification, and specific activity at each stage are given in Table 1. The crude PI extract was subjected to 0–25% and 25–50% ammonium sulfate fractionation. The pellet obtained from 25 to 50% saturation was dialyzed and subjected to CM-cellulose chromatography. The elution profile of CM-cellulose chromatography is shown in Figure 1A. Three protein peaks were eluted and designated as Fraction-I, -II, and -III. Fraction-I was not adsorbed onto the CM-cellulose column at pH 5.7 and hence eluted along the start buffer. Fraction-II and Fraction-III were eluted with 0.1 and 0.3 M NaCl in the start buffer at pH 5.7. Fraction-II containing appreciable levels of PI activity was pooled, concentrated, and subjected to Sephadex G-75 gel filtration chromatography. The elution profile of Sephadex G-75 chromatography at pH 5.7 is shown in Figure 1B. Both the protein and PI were eluted together in a single fraction, followed by subjecting this fraction to preparative PAGE. Fold purification of the resultant PI on preparative PAGE was nearly 56%, whereas its specific inhibitor activity was 202.31 TIU/mg (Table 1). The analysis of the purification profile of the PI on reverse zymography and cationic native PAGE showed a single PI activity band corresponding to a single protein band (Figures 2A,B).

TABLE 1.

Purification profile of cationic serine protease inhibitor from Mucuna pruriens seeds.

| Purification steps | Protein (mg) | TIU | Specific inhibitory activity (TIU/mg) | % yield | Fold of purification |

| Crude | 4735.5 | 17,200 | 3.6 | 100 | 1 |

| ASF 25–50% | 571.3 | 7,200 | 10.7 | 42 | 3 |

| CM-cellulose chromatography | 170.5 | 5,430 | 32 | 31.6 | 8.7 |

| Sephadex G-75 chromatography | 50.1 | 3,680 | 73.5 | 21.4 | 20.2 |

| Preparative PAGE (MPTI) | 5.2 | 1,050 | 202.3 | 6.1 | 55.7 |

TIU, Trypsin inhibitor units; ASF, ammonium sulfate fraction; MPTI, Mucuna pruriens trypsin inhibitor; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

FIGURE 1.

Separation of protease inhibitors (PIs) during ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography. (A) Elution profile on CM-cellulose chromatography and (B) elution profile on Sephadex G-75 chromatography.

FIGURE 2.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) pattern of proteins and PI profile of Mucuna pruriens seeds. (A) Protein staining and (B) protease inhibitor(PI) staining. Lanes in gel: 1. crude inhibitor extract, 2. ammonium sulfate fraction (25–50%), 3. CM-cellulose fraction-II, 4. Sephadex G-75 fraction, and 5. preparative PAGE fraction.

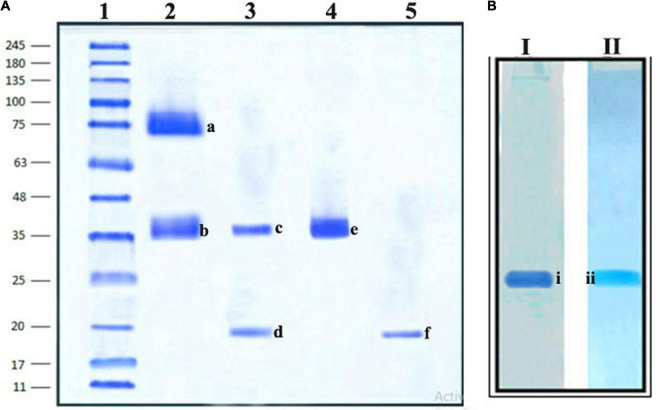

Electrophoretic Analysis: Criteria of Purity

The homogeneity of the purified trypsin inhibitor was established using native PAGE and SDS–PAGE. The preparative PAGE fraction was subjected to SDS–PAGE under both non-reducing and reducing conditions. The non-reducing SDS–PAGE showed the presence of two protein bands corresponding to 74 kDa (TINR-74) and 37 kDa (TINR-37) bands. In contrast, the reducing SDS–PAGE showed the presence of two protein bands corresponding to 37 (TIR-37) and 18 kDa (TIR-18). TINR-37 band was eluted from the gel and further subjected to SDS–PAGE under both reducing and non-reducing conditions. Accordingly, the presence of 37 and 18 kDa proteins in the non-reducing and reducing gels, respectively, confirmed the dimeric nature of the purified PI. Cationic native PAGE of the TINR-37 inhibitor showed a single PI activity corresponding to a single protein band (Figures 3A,B).

FIGURE 3.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–PAGE and Native PAGE of Mucuna pruriens trypsin inhibitor (MPTI). (A) SDS–PAGE of preparative PAGE fraction. Lanes: 1. standard marker proteins (kDa), 2. preparative PAGE fraction (non-reducing), 3. preparative PAGE fraction (reducing), 4. SDS–PAGE fraction b (non-reducing), and 5. SDS–PAGE fraction b (reducing). a: Trypsin inhibitor non-reducing (TINR)-74 kDa, b and e: TINR-37 kDa, c: trypsin inhibitor reducing (TIR)-37 kDa, d and f: TIR-18 kDa. (B) Native PAGE of SDS–PAGE fraction, (i) native protein PAGE and (ii) native zymogram PAGE.

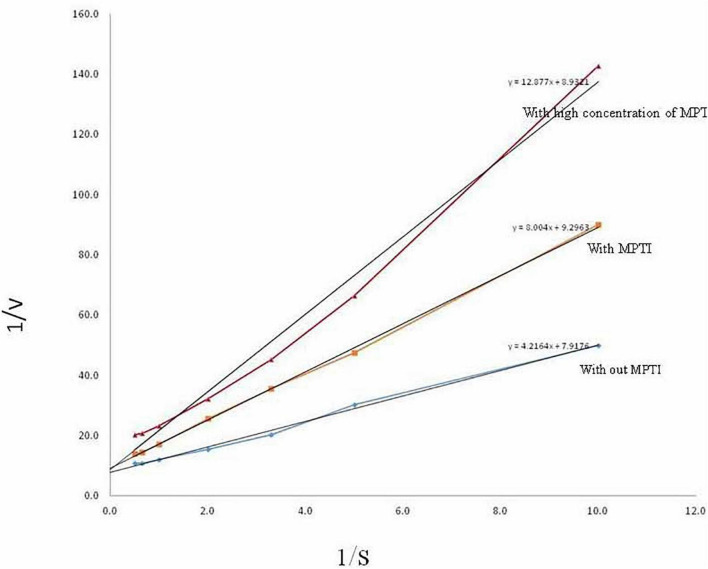

Determination of km, Vmax, and ki

The inhibitory activity of MPTI was determined against bovine trypsin by measuring the residual activity toward BAPNA as a substrate. km and Vmax of trypsin were determined as 0.126 mM and 0.532 μmol/min, respectively, using the Lineweaver–Burk plots (Figure 4). The altered km and Vmax of trypsin at low and high concentrations of MPTI were 0.862 and 1.443 mM, as well as 0.108 and 0.113 μmol/min, respectively. The increased km in the presence of MPTI indicated that MPTI acts as a competitive inhibitor. ki was found to be 1.3 × 10–6 M.

FIGURE 4.

Determination of km and Vmax of trypsin in the presence of Mucuna pruriens trypsin inhibitor (MPTI).

Characterization of Multimeric Forms of Purified TI Based on Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization/Quadrupole Time-of-Flight-Mass Spectrometry

The four trypsin inhibitor bands (i.e., TINR-74, TINR-37, TIR-37, and TIR-18) were extracted from the electrophoretic gels and subjected to UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS. TIR-18 and TIR-37 revealed the presence of 37.39 and 18.695 kDa peaks (Figures 5, 6), respectively. TINR-74 was observed to contain multiple peaks of varying MWs, i.e., 18.695, 37.39, 56.085, and 74.78 kDa (Figure 7), whereas TINR-37 revealed the presence of peaks at 18.695 and 37.39 kDa (Figure 8). These results indicated that the purified PI fraction showed an association of multimeric forms under native conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS) analysis of TIR-18.

FIGURE 6.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS) analysis of TIR-37.

FIGURE 7.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS) analysis of TINR-74.

FIGURE 8.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS) analysis of TINR-37.

Anti-inflammatory Activity

The purified MPTI was used to test the stabilization of the RBC membrane, whereby MPTI showed maximum stabilization at a concentration of 300 μg/ml MPTI (Supplementary Figure 1). This revealed that the purified PI can act as a potent anti-inflammatory agent, which indicates that the presence of multimeric association may assist in increased efficiency and stability to the MPTI.

Discussion

The PIs are the proteolytic enzyme inhibitors reported from several legumes and explored for many applications in agriculture and biotechnology (Srikanth and Chen, 2016; Clemente et al., 2019). M. pruriens, being an underutilized legume, is rich in protein and contains various bioactive molecules such as PIs (Lone et al., 2021). Although PI is present, the acid-resistant PI with its multimeric forms is yet to be explored. On this basis, the proteinaceous PI was purified and characterized from M. pruriens.

The PI was isolated from M. pruriens by acid extraction and partially purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation. It was found that 30–60% ammonium sulfate saturation obtained here contained the highest content of protease inhibitory activity. Previously, PIs (30–40 kDa) have been fractionated with 50% ammonium sulfate saturation from the Australian wattle seed Acacia victoriae Bentham (Ee et al., 2008). Further purification was performed by employing CM-cellulose and Sephadex G-75 chromatography. PI with an MW of 43 kDa was isolated and purified from duck egg albumin using salt fractionation, affinity, and gel filtration chromatography techniques (Quan and Benjakul, 2019). Protein recovery and fold can be increased by combining different purification methods. The fold purification obtained in this study is comparatively higher when compared to Acacia nilotica seeds (Babu et al., 2012). PIs reported from various legumes ranged from 19- to 489-fold purification level (Godbole et al., 1994; Hajela et al., 1999; Oliveira et al., 2002; Rai et al., 2008).

The purification of PI from the seeds of M. pruriens showed satisfactory specific activity when isolated through acid extraction, and during all stages of the purification, it revealed a single protein band on native PAGE with their corresponding trypsin inhibitor on native reverse zymography PAGE, which confirmed that only acid-resistant PI is present. SDS–PAGE under non-reductive and reducing conditions revealed the MWs of 37 and 18 kDa of purified PI, which confirmed the presence of monomer and dimeric forms. Earlier, a 34-kDa PI has been characterized using SDS–PAGE from Putranjiva roxburghii seeds previously (Chaudhary et al., 2008). The presence of this self-association to form multimers was identified by UPLC-ESI/QTOF-based MS. This analysis confirmed that the purified MPTI exhibited multimeric forms that are essential for its molecular packing and assembly as a storage protein in seeds (Chaudhary et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2010). In addition, these analyses showed that the purified MPTI fraction belongs to the BBI family. BBIs are well-known to undergo spontaneous self-associations to form homodimers, trimers, or even more complex oligomers, which constitute multimeric forms (Gennis and Cantor, 1976; Odani and Ikenaka, 1978; Terada et al., 1994; Catalano et al., 2003; Kumar et al., 2004, 2015; Silva et al., 2005; Rao and Suresh, 2007; Brand et al., 2017). Traditionally, the BBIs have rich cysteine residues and have multiple hydrophobic groups, which favor them in forming various intermolecular interactions. Such interactions exist in their native state. The light-scattering method has been used to establish the association of monomers and several multimers (i.e., dimers, trimers, tetramers, and hexamers) in BBIs (de Freitas et al., 1997). The association of subunits in BBIs is due to a strong network of hydrogen bonds between the buried charged residues and exposed hydrophobic surface patches; this helps in the self-association of the protein and stabilizes the disulfide bonds by forming an electrically charged, constrained, rigid monomeric structure (Silva et al., 2005; Rao and Suresh, 2007; Joshi et al., 2013). Some studies reported the pivotal role of charged interactions in the case of monomer/dimer equilibria (Kumar et al., 2004). During the MS analyses, the non-covalent interactions break down, resulting in separate peaks, thereby confirming the multimeric association. It has been reported that the multimeric association between peptides/proteins is due to the formation of ionic bonding between Ca2+ ions and glutamate (E) and aspartate (D) residues or hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups (OH) of threonine (T) and/or serine (S) with the neighboring or asparagine (N) and tyrosine (Y) residues. Moreover, peptides/proteins with more number of asparagine (N) and tyrosine (Y) residues can help in increasing binding potential (Jamalian et al., 2014). In horse gram, the stabilization of dimers is due to the electrostatic interaction between Lys-24 and Asp-75 = 76 residues of N- and C-terminal ends (Kumar et al., 2004; Muricken and Gowda, 2010). However, the mechanism of self-association may vary among various BBI molecules. The multimeric states of trypsin inhibitor were too identified by the atomic force microscopy analysis, which indicated that the inhibitor adopts stable and well-packed self-associated states in monomer-dimer-trimer-hexamer forms with globular-ellipsoidal shapes (Silva et al., 2005). The absence of a more hydrophobic core and the presence of the high content of disulfide bonds result in a constrained conformation that may be responsible for the remarkable stability and association exhibited by this inhibitor (da Silva et al., 2001), in covenant with other BBIs (Voss et al., 1996). It has been reported that the reactive sites that show interaction with proteases are generally located on the surface of the dimer, which most likely indicates that the dimeric form is the functional state of the molecule (Li de la Sierra et al., 1999). The multimeric association shown by the BBI type of inhibitors is a natural fundamental characteristic feature that helps them to achieve more stability, thus enhancing their functional efficiency. Due to this association, BBIs are more resistant to extreme acidic extraction. Furthermore, the self-association tendency to form the multimeric forms is mostly related to the physiological function of BBI as it acts as a plant storage protein, which facilitates their tight packing in seeds (Catalano et al., 2003; Hogg, 2003; Kumar et al., 2015). In this study, UPLC coupled with ESI/QTOF-MS confirmed the multimeric association of purified SPI belonging to the BBI family of PIs.

The molecular masses determined by both SDS–PAGE and UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS were found higher as compared to reported BBIs. This is in accordance with those found for BBIs from other species (Gladysheva et al., 1994; Yan et al., 2009; Chevreuil et al., 2014; Al-Maiman et al., 2019). Regarding the existence of multiple forms or higher MWs, it may be possible that this happens due to the evolution through gene duplication, where it has been reported that 16 kDa inhibitor was evolved by gene duplication from 8 kDa inhibitor (Song et al., 1999). This suggested that the purified PI from the seeds of M. pruriens is a novel BBI.

Furthermore, the kinetic analysis suggests that MPTI forms a more stable complex with trypsin by increased km in the presence of MPTI, which indicated that MPTI acts as a competitive inhibitor. The tendency of forming a high-affinity complex toward trypsin interestingly indicated that most BBI belongs to competitive inhibition. MPTI exhibited a ki value of 1.3 × 10–6 M. PIs with ki values ranging between 0.0001 and 5.2 mM are the characteristics of BBIs (Prasad et al., 2010). Earlier, it was reported that the ki value of PIs from different plant sources (5.3 × 10–10 M in Dimorphandra mollis, 1.7 × 10–9 M in D. mollis, 2.5 × 10–10 M in Archidendron ellipticum, and 1.4 × 10–11 M in P. roxburghii seeds) was quite less as compared to MPTI (Macedo et al., 2000; Mello et al., 2001; Bhattacharyya et al., 2006; Chaudhary et al., 2008).

Proteases, being clinically important molecules, are putative drug targets among which serine proteases comprise a major portion. Model SPs such as chymotrypsin, trypsin, pancreatic elastase, or several blood coagulation factors became the hotspots for the drug target and discovery of PIs (López-Otín and Matrisian, 2007; Drag and Salvesen, 2010). Most of the animal proteases are still unexplored as drug targets. Several studies have reported that various proteases are involved in arthritic reactions and tissue damage during inflammation. Among them, serine protease is the most actively involved in inflammation, causing the stimulation of eosinophils through protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) response (King et al., 2000; Miike et al., 2001). On this basis, we analyzed the role of MPTI in inhibiting the membrane disruption on RBC hemolysis. It was found that MPTI exhibited potent anti-inflammatory activity. BBIs have been used to cure the inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, which manifest that the chronic inflammation of tissues results in elevating the activity of plasma proteases (Juritsch and Moreau, 2018). In addition, inflammation can also be caused by the denaturation of proteins. The anti-inflammatory drugs, such as phenylbutazone and salicylic acid, have been reported, which inhibit protein denaturation (Selvi and Bhaskar, 2012). It has also been studied that Plant PIs may inhibit the action of proteinases, bactericidal enzymes, and neutrophils released from lysosomes at the site of inflammation, which, on extracellular release, cause further tissue inflammation and damage (Armstrong, 2001; Pham, 2006). Therefore, this extracellular inhibition of the protease can help in directing specific drug targets and will result in the development of novel natural drug therapeutics.

Conclusion

The UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS is a powerful technique for the exact mass calculation of proteins. The cationic SPI was identified, purified, and characterized from the seeds of an underutilized legume, i.e., M. pruriens employing acid extraction, salt precipitation, CM-cellulose, Sephadex G-75 chromatography, preparative native, and SDS–PAGE. The homogeneity of the purified inhibitor was established by native and SDS–PAGE. The MW of the purified inhibitor was determined to be 18.3 kDa in monomeric form and 37.63 kDa in dimeric form, via UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS. Furthermore, the multimeric association of the purified PI was characterized by UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS. This self-association may arise due to non-covalent interactions between the intact proteins. This characterization study revealed the association of multimeric forms of cationic trypsin inhibitors in the seeds of M. pruriens, which specified its nature toward the BBI family. Furthermore, the purified inhibitor was determined as a competitive inhibitor and exhibited potent anti-inflammatory activity. Apart from pest resistance in plants, purified MPTI can be used in the medical field to evaluate its potential as a curative measure for inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

JL conducted the research and wrote the manuscript. ML, RB, and FA performed the data analyses and reviewed the manuscript. SW, MP, and JY edited and reviewed the manuscript. KC planned, supervised, and organized the experiment and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged the Department of Biochemistry, Jnana Kaveri Campus Mangalore University for providing the research facility. We are thankful to Hima Bindu K., ICAR-Indian Institute of Horticulture Research, Bangalore, India, for providing the M. pruriens seeds.

Abbreviations

- PI

Protease inhibitor

- SPIs

serine protease inhibitors

- BBI

Bowman-Birk inhibitor

- MPTI

Mucuna pruriens trypsin inhibitor

- TIR

trypsin inhibitor reducing

- TINR

trypsin inhibitor non-reducing

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- UPLC-ESI/QTOF-MS

ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry

- CaCl2

calcium chloride

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- km

substrate concentration

- Vmax

velocity maximum

- RBC

red blood cells.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.772046/full#supplementary-material

Anti-inflammatory activity of MPTI.

References

- Al-Maiman S. A., Gassem M. A., Osman M. A., Ahmed I. M., Al-Juhaimi F. Y., Rahman I. A., et al. (2019). Bowman-Birk proteinase inhibitor from tepary bean (Phaseolusacutifolius) seeds: purification and biochemical properties. Int. Food Res. J. 26 1123–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Arentoft A. M., Frøkiær H., Michaelsen S., Sørensen H., Sørensen S. (1993). High-performance capillary electrophoresis for the determination of trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors and their association with trypsin, chymotrypsin and monoclonal antibodies. J. Chromatogr. A 652 189–198. 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80659-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong P. B. (2001). The contribution of proteinase inhibitors to immune defense. Trends Immunol. 22 47–52. 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01803-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu S. R., Subrahmanyam B., Santha I. M. (2012). In vivo and in vitro effect of Acacia nilotica seed proteinase inhibitors on Helicoverpaarmigera (Hübner) larvae. J. Biosci. 37 269–276. 10.1007/s12038-012-9204-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj R. P., Raju N. G., Chandrashekharaiah K. S. (2018). Purification and characterization of alpha-amylase inhibitor from the seeds of underutilized legume, Mucuna pruriens. J. Food Biochem. 42:e12686. 10.1111/jfbc.12686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A., Mazumdar S., Leighton S. M., Babu C. R. (2006). A Kunitz proteinase inhibitor from Archidendron ellipticum seeds: purification, characterization, and kinetic properties. Phytochemistry 67 232–241. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode W., Huber R. (2000). Structural basis of the endoproteinase–protein inhibitor interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1477 241–252. 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00276-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag D. M., Edelstein S. J., Rozycki M. D. (1996). Proteins Methods. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brand G. D., Pires D. A. T., Furtado J. R., Jr., Cooper A., Freitas S. M., Bloch C., Jr. (2017). Oligomerization affects the kinetics and thermodynamics of the interaction of a Bowman-Birk inhibitor with proteases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 618, 9–14. 10.1016/j.abb.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano M., Ragona L., Molinari H., Tava A., Zetta L. (2003). Anticarcinogenic Bowman Birk inhibitor isolated from snail medic seeds (Medicago scutellata): solution structure and analysis of self-association behavior. Biochemistry 42 2836–2846. 10.1021/bi020576w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekharaiah K. S., Swamy N. R., Murthy K. S. (2011). Carboxylesterases from the seeds of an underutilized legume, Mucuna pruriens; isolation, purification and characterization. Phytochemistry 18, 2267–2274. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N. S., Shee C., Islam A., Ahmad F., Yernool D., Kumar P., et al. (2008). Purification and characterization of a trypsin inhibitor from Putranjiva roxburghii seeds. Phytochemistry 69 2120–2126. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevreuil L. R., Gonçalves J. F. D. C., Calderon L. D. A., Souza L. A. G. D., Pando S. C. (2014). Partial purification of trypsin inhibitors from Parkia seeds (Fabaceae). Hoehnea 41 181–186. 10.1590/S2236-89062014000200003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente M., Corigliano M. G., Pariani S. A., Sánchez-López E. F., Sander V. A., Ramos-Duarte V. A. (2019). Plant serine protease inhibitors: biotechnology application in agriculture and molecular farming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:1345. 10.3390/ijms20061345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors B. J., Laun N. P., Maynard C. A., Powell W. A. (2002). Molecular characterization of a gene encoding a cystatin expressed in the stems of American chestnut (Castaneadentata). Planta 215 510–514. 10.1007/s00425-002-0782-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristina Oliveira de Lima V., Piuvezam G., Leal Lima Maciel B., Heloneida de Araújo Morais A. (2019). Trypsin inhibitors: promising candidate satietogenic proteins as complementary treatment for obesity and metabolic disorders? J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 34 405–419. 10.1080/14756366.2018.1542387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva L., Sa Leite J. R., Bloch C., Jr., de Freitas S. (2001). Stability of a black eyed pea trypsin chymotrypsin inhibitor (BTCI). Protein Pept. Lett. 8 33–38. 10.2174/0929866013409715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas S. M., de Mello L. V., da Silva M. C. M., Vriend G., Neshich G., Ventura M. M. (1997). Analysis of the black-eyed pea trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitor-α-chymotrypsin complex. FEBS Lett. 409 121–127. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00419-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drag M., Salvesen G. S. (2010). Emerging principles in protease-based drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9 690–701. 10.1038/nrd3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ee K. Y., Zhao J., Rehman A., Agboola S. (2008). Characterisation of trypsin and α-chymotrypsin inhibitors in Australian wattle seed (Acacia victoriae Bentham). Food Chem. 107 337–343. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eschelbach J. W., Jorgenson J. W. (2006). Improved protein recovery in reversed-phase liquid chromatography by the use of ultrahigh pressures. Anal. Chem. 78 1697–1706. 10.1021/ac0518304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everley R. A., Croley T. R. (2008). Ultra-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry of intact proteins. J. Chromatogr. A 1192 239–247. 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.03.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felicioli R., Garzelli B., Vaccari L., Melfi D., Balestreri E. (1997). Activity staining of protein inhibitors of proteases on gelatin-containing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 244 176–179. 10.1006/abio.1996.9917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli L., Businaro R., Nori S. L., Toesca A., Pompili E., Evangelisti E., et al. (1996). Protease inhibitors in mouse skeletal muscle: tissue-associated components of serum inhibitors and calpastatin. Cell Mol. Biol. 42 535–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennis L. S., Cantor C. R. (1976). Double-headed protease inhibitors from black-eyed peas. III. Subunit interactions of the native and half-site chemically modified proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 251 747–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin-Domagalska A., Maciejewska A., Dêbowski D. (2020). Bowman-Birk Inhibitors: insights into family of multifunctional proteins and peptides with potential therapeutical applications. Pharmaceuticals 13:421. 10.3390/ph13120421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladysheva I. P., Sharafutdinov T. Z., Larionova N. I. (1994). High molecular weight soy isoinhibitors of the Bowman-Birk type. Isolation, characteristics, and kinetics of interaction with proteinases. Bioorg. Khim. 20 281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbole S. A., Krishna T. G., Bhatia C. R. (1994). Purification and characterisation of protease inhibitors from pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan (l) millsp) seeds. J. Sci. Food Ayric. 64 87–93. 10.1002/jsfa.2740640113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerranti R., Aguiyi J. C., Leoncini R., Pagani R., Cinci G., Marinello E. (1999). Characterization of the factor responsible for the antisnake activity of Mucuna pruriens seeds. J Prev Med Hyg. 1 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hajela N., Pande A. H., Sharma S., Rao D. N., Hajela K. (1999). Studies on a double headed protease inhibitor from Phaseolus mungo. J. Plant Biochem. Biotech. 8 57–60. 10.1007/bf03263059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger R., Gruber C. W. (2019). Peptide-based protease inhibitors from plants. Drug Discov. Today 24 1877–1889. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg P. J. (2003). Disulfide bonds as switches for protein function. Trends Biochem Sci. 28 210–214. 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamalian A., Sneekes E.-J., Dekker L. J., Ursem M., Luider T. M., Burgers P. C. (2014). Dimerization of peptides by calcium ions: investigation of a calcium-binding motif. Int. J. Proteomics 2014:153712. 10.1155/2014/153712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R. S., Mishra M., Suresh C. G., Gupta V. S., Giri A. P. (2013). Complementation of intramolecular interactions for structural–functional stability of plant serine proteinase inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830 5087–5094. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R. S., Tanpure R. S., Singh R. K., Gupta V. S., Giri A. P. (2014). Resistance through inhibition: ectopic expression of serine protease inhibitor offers stress tolerance via delayed senescence in yeast cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 452 361–368. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juritsch A. F., Moreau R. (2018). Role of soybean-derived bioactive compounds in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutr. Rev. 76 618–638. 10.1093/nutrit/nuy021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H., Itoh H., Koono M. (2002). Emerging multifunctional aspects of cellular serine proteinase inhibitors in tumor progression and tissue regeneration. Pathol. Int. 52 89–102. 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G. J. (1999). Human genetic diseases of proteolysis. Hum. Mutat. 13 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenschlager R., Evans A., Manson A., Patsalos P. N., Ratnaraj N., Watt H., et al. (2004). Mucuna pruriens in Parkinson’s disease: a double blind clinical and pharmacological study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75 1672–1677. 10.1136/jnnp.2003.028761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. K., Turner R., Khazan N., Kodza A., Jones A., Singh R. K., et al. (2020). Role of trypsin and protease-activated receptor-2 in ovarian cancer. PLoS One 15:e0232253. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. E., Critchley H. O., Kelly R. W. (2000). Presence of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in human endometrium and first trimester decidua suggests an antibacterial protective role. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 6 191–196. 10.1093/molehr/6.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Rao A. A., Hariharaputran S., Chandra N., Gowda L. R. (2004). Molecular mechanism of dimerization of Bowman-Birk inhibitors: pivotal role of Asp76 in the dimerzation. J. Biol. Chem. 279 30425–30432. 10.1074/jbc.M402972200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Murugeson S., Vithani N., Prakash B., Gowda L. R. (2015). A salt-bridge stabilized C-terminal hook is critical for the dimerization of a Bowman Birk inhibitor. Arch. Biochem Biophys. 566 15–25. 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227 680–685. 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li de la Sierra I., Quillien L., Flecker P., Gueguen J., Brunie S. (1999). Dimeric crystal structure of a Bowman-Birk protease inhibitor from pea seeds. J. Mol. Biol. 285 1195–1207. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver H., Burk D. (1934). The determination of enzyme dissociation constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 56 658–666. 10.1021/ja01318a036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lone J. K., Lekha M. A., Ali F., Bharadwaj R. P., Chandrashekharaiah K. S. (2021). Comparative study on total soluble proteins of various Mucuna Species and dissecting their role in trypsin inhibition. Appl. Biol. Res. 23 13–20. 10.5958/0974-4517.2021.00002.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C., Matrisian L. M. (2007). Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 800–808. 10.1038/nrc2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo M. L., de Matos D. G. G., Machado O. L., Marangoni S., Novello J. C. (2000). Trypsin inhibitor from Dimorphandra mollis seeds: purification and properties. Phytochemistry 54 553–558. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenatchisundaram S., Michael A. (2010). Antitoxin activity of Mucuna pruriens aqueous extracts against Cobra and Krait venom by in vivo and in vitro methods. Int. J. Pharm. Tech. Res. 2 870–874. [Google Scholar]

- Mello G. C., Oliva M. L. V., Sumikawa J. T., Machado O. L., Marangoni S., Novello J. C., et al. (2001). Purification and characterization of a new trypsin inhibitor from Dimorphandra mollis seeds. J. Protein Chem. 20 625–632. 10.1023/A:1013764118579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miike S., McWilliam A. S., Kita H. (2001). Trypsin induces activation and inflammatory mediator release from human eosinophils through protease-activated receptor-2. J. Immunol. 167 6615–6622. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima Y., Kobayashi M. (1968). Interaction of anti-inflammatory drugs with serum proteins, especially with some biologically active proteins. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 20 169–173. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muricken D. G., Gowda L. R. (2010). Functional expression of horsegram (Dolichos biflorus) Bowman–Birk inhibitor and its self-association. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics 1804 1413–1423. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg P., Ylipalosaari M., Sorsa T., Salo T. (2006). Trypsin and their role in carcinoma growth. Exp. Cell Res. 312 1219–1228. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odani S., Ikenaka T. (1978). Studies on soybean trypsin Inhibitors: XIII. preparation and characterization of active fragments from Bowman-Birk proteinase inhibitor. J. Biochem. 83 747–753. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira A. S., Pereira R. A., Lima L. M., Morais A. H., Melo F. R., Franco O. L., et al. (2002). Activity toward bruchid pest of a Kunitz-type inhibitor from seeds of the algaroba tree (Prosopis juliflora DC). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 72 122–132. 10.1006/pest.2001.2591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C., Van Doorn W. G. (2005). Delay of Iris flower senescence by protease inhibitors. New Phytol. 165 473–480. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham C. T. (2006). Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6 541–550. 10.1038/nri1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad E. R., Dutta-Gupta A., Padmasree K. (2010). Purification and characterization of a Bowman-Birk proteinase inhibitor from the seeds of black gram (Vigna mungo). Phytochemistry 71 363–372. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan T. H., Benjakul S. (2019). Trypsin inhibitor from duck albumen: purification and characterization. J. Food Biochem. 43:e12841. 10.1111/jfbc.12841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai S., Aggarwal K. K., Babu C. R. (2008). Isolation of a serine Kunitz trypsin inhibitor from leaves of Terminalia arjuna. Curr. Sci. 94 1509–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. N., Suresh C. G. (2007). Bowman–Birk protease inhibitor from the seeds of Vigna unguiculata forms a highly stable dimeric structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774 1264–1273. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings N. D., Barrett A. J., Thomas P. D., Huang X., Bateman A., Finn R. D. (2018). The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 D624–D632. 10.1093/nar/gkx1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisfeld R. A., Lewis U., Williams D. E. (1962). Disk electrophoresis of basic proteins and peptides on polyacrylamide gels. Nature 195 281–283. 10.1038/195281a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustgi S., Boex-Fontvieille E., Reinbothe C., von Wettstein D., Reinbothe S. (2017). Serpin1 and WSCP differentially regulate the activity of the cysteine protease RD21 during plant development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114 2212–2217. 10.1073/pnas.1621496114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvi V. S., Bhaskar A. (2012). Characterization of anti-inflammatory activities and antinociceptive effects of papaverine from Sauropus androgynus L. Merr. Global. J Pharmacol. 6 186–192. 10.5829/idosi.gjp.2012.6.3.65179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H., Hara S., Ikenaka T., Abe J. (1986). Purification and characterization of proteinase inhibitors from winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.) seeds. J. Biochem. 99 1147–1155. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva L. P., Azevedo R. B., Morais P. C., Ventura M. M., Freitas S. M. (2005). Oligomerization states of Bowman-Birk inhibitor by atomic force microscopy and computational approaches. Proteins 61 642–648. 10.1002/prot.20646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H. K., Kim Y. S., Yang J. K., Moon J., Lee J. Y., Suh S. W. (1999). Crystal structure of a 16 kDa double-headed Bowman-Birk trypsin inhibitor from barley seeds at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 293 1133–1144. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth S., Chen Z. (2016). Plant protease inhibitors in therapeutics-focus on cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 7:470. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan N. H., Fung S. Y., Sim S. M., Marinello E., Guerranti R., Aguiyi J. C. (2009). The protective effect of Mucuna pruriens seeds against snake venom poisoning. J. Ethnopharmacol. 123 356–358. 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada S., Fujimura S., Kino S., Kimoto E. (1994). Purification and characterization of three proteinase inhibitors from Canavalia lineata seeds. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 58 371–375. 10.1271/bbb.58.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M. G., Palmer R. M. (1998). Signalling pathways regulating protein turnover in skeletal muscle. Cell. Signal. 10 1–11. 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00076-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss R. H., Ermler U., Essen L. O., Wenzl G., Kim Y. M., Flecker P. (1996). Crystal Structure of the Bifunctional Soybean Bowman-Birk Inhibitor at 0.28 nm Resolution: structural peculiarities in a folded protein conformation. Eur. J. Biochem. 242 122–131. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0122r.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Hoi K. M., Stöckmann H., Wan C., Sim L., Bte Kamari Shi Jie Tay N. H., et al. (2018). LC/MS-based Intact IgG and Released Glycan Analysis for Bioprocessing Applications. Biotechnol. J. 13:e1700185. 10.1002/biot.201700185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter L. R. (1957). Some properties of the lipase present in germinating rapeseed. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 34 66–70. 10.1007/BF02638019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K. M., Chang T., Soon S. A., Huang F. Y. (2009). Purification and characterization of Bowman-Birk protease inhibitor from rice coleoptiles. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 56 949–960. 10.1002/jccs.200900139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yasin J. K., Mishra B. K., Pillai M. A., Verma N., Wani S. H., Elansary H. O., et al. (2020). Genome wide in-silico miRNA and target network prediction from stress responsive Horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum) accessions. Sci. Rep. 10:17203. 10.1038/s41598-020-73140-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasin J. K., Nizar M. A., Rajkumar S., Verma M., Verma N., Pandey S., et al. (2014). Existence of alternate defense mechanisms for combating moisture stress in horse gram [Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.]. Legume Res. 1 145–154. 10.5958/j.0976-0571.37.2.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. Y., Dann G. P., Shi T., Wang L., Gao X., Su D., et al. (2012). Simple sodium dodecyl sulfate-assisted sample preparation method for LC-MS-based proteomics applications. Anal. Chem. 84 2862–2867. 10.1021/ac203394r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Anti-inflammatory activity of MPTI.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.