Abstract

Background

Knowledge and attitude towards mental illness are poor and neglected as compared to medical illness. However, there is an increasing burden of mental illness in the community. As per the knowledge of the investigators, studies are scarce and not done in the study area about knowledge and attitudes of mental illness. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, and associated factors towards mental illness among, Dessie town residents.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Dessie town, Northeast, Ethiopia from October 27 to November 29/2020. A multi-stage sampling technique was employed. The data were collected from 477 study participants using a standard structured questionnaire, which were Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS) and Community Attitude to Mental Illness Inventory (CAMI) respectively. Data were entered using Epi-data version 3.1 and, then exported to SPSS version 26 for analyses. Bivariable and Multivariable logistic regression analyses was employed.

Results

From 477 study participants the prevalence of poor knowledge and unfavorable attitude towards mental illness were 55.3% (95% CI: 50.9, 60.0) and 45.1% (95% CI: 40.7,49.5) respectively. Being female [AOR = 1.62 (95% CI:1.06,2.47)], could not read and write [AOR = 6.28 (95% CI: 2.56, 15.39)], lack of information about mental illness [AOR = 5.82 (95% CI: 3.78,8.94)] and unfavorable attitude [AOR =1.73 (95% CI: 1.12,2.66)] were variables found statistical significant with poor knowledge. Whereas, income < 2166 [AOR = 1.64, (95% CI: 1.12, 2.41)], poor social support [AOR = 2.04, (95% CI: 1.13, 3.68)], moderate social support [AOR = 2.44, (95% CI: 1.45, 3.97)] and poor knowledge [AOR = 1.66, (95% CI: 1.13,2.43)] were variables significantly associated with unfavorable attitude toward mental illness.

Conclusion

In this study about half of the community have poor knowledge, and less than half of the participants have an unfavorable attitude to wards mental illness. There are many factors associated with poor knowledge and unfavorable attitudes. This having poor knowledge and unfavorable attitude may cause certain problems like a decrease in health care of a person with mental illness. Therefore, we recommend practice-based awareness in the community regarding mental health problems needs to be addressed.

Keywords: Knowledge, Attitude, Mental illness, Factors, Dessie, Ethiopia

Background

Mental illness is a term used to describe a broad range of mental and emotional disturbances affecting individuals thinking, feeling, decision making, mood, daily functioning as well as ability to relate to others [1, 2]. According to Gill, causes of mental illness are not synonymous, but vary widely, from inherited chemical imbalances accountable for the development of such illnesses as depression and bipolar disorder [3]. Globally, 450 million people are predicted to be suffering from psychiatric disorders. However, in our day-to-day activity mental, physical, and social health are the necessary components in every individual [4]. In addition, according to a WHO report, globally more than 25% of people are experienced mental illness at some point in their lifetime. The Nationwide Institution of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States also estimates that 1 in 5 people (20%) would be affected by this condition at some point in their lives [5].

Currently, mental illness is a public health problem in developed as well as developing countries [6]. However, studies suggest that some mental disorders are even common in low income than in developed, it is estimated by the year 2000 there would be 24.4 million schizophrenia in less developed countries [6, 7]. The prevalence of poor knowledge is significantly very high in deferent countries, in Qatar 72.5% [8], in Saudi public 87.5% [9], in Tanzania 85.9% [10], in Kinondoni 61% [3], in Nigeria 51.2% [11], in Moroccan 76% [12], and in Ethiopia 59.2% [13]. Whereas unfavorable attitude, in Tanzania 58.9% [10], in Kinondoni 79.6% [3], Saudi public 54.5% [9] and Nigeria 10.0% [11].

In Ethiopia, there are widespread beliefs that severe mental illness is due to demon possession, or the evil eye has existed for many years, this influence the attitude towards mental illness [14]. In Ethiopia, where preventable infectious diseases are very widespread, has got great attention. But mental health problems, which are regarded as non-life-threatening problems, due to this, are not given attention. However, mental health problems account for 12.45% of the burden of diseases in Ethiopia and 12% of the Ethiopian people are suffering from some form of mental health problems of which, 2% are severe cases [15, 16].

Previous studies reported that there are several identified factors associated with poor knowledge and unfavorable attitude, have low educational attainment, unemployment, age, sex, poor levels of social support, low income, absence of relative with a mental disorder, unemployed history of mental illness who do not have better information access to mental illness [3, 8, 9, 11, 13, 17–25]. About 14% of the global burden of disease have been attributed to mental and related disease, mostly chronically disabling illness, depression and other common mental disorders like psychosis [26]. Of all the health problems, mental illnesses are poorly understood by the universal in the community. Such poor knowledge and negative attitude towards mental illness threaten the success of patient care, rehabilitation, the healing process, unable to use effective treatment, lead to stigmatization, inhibit help-seeking behavior and provide proper holistic care [4, 5]. Furthermore, negative attitudes and discrimination deprive victims of human dignity and prevent social participation. These negative experiences decrease self-esteem and instill feelings of shame and guilt [26].

Despite mental illness is a significant problem globally, especially in Dessie town,Ethiopia [27],and it is on the rise associated with deep-rooted little knowledge and negative attitude toward mental. Even, if there are several studies done on knowledge and attitude towards mental illness in Ethiopia [13, 28–30]. To the best of our knowledge, no study assessed the community knowledge and attitude towards mental illness in Dessie town residents, Ethiopia. Therefore, this study finding will have added greatly to the current knowledge by giving appropriate evidence that will be significantly important for health planners, decision-makers, future researchers, and politicians.

Methods and materials

Study area, design, and period

A Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from October 27 to November 29/2020 in Dessie town, South Wollo zone, North East, Ethiopia. The town is geographically located 401 km from Addis Ababa to the northeast part of Ethiopia. It has five sub-town with a total population of 350,000. Among those populations 186,571 males and 163,429 females according to 2016 to 2017 South Wollo Zone statistics office data.

Source of population

All residents of Dessie town, North East, Ethiopia.

Study population

Households live in the Menafesha sub-town who are in the selected kebele and available during the study period.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All households in selected kebeles,who was > 18 years old, and participants living > 6 months in Dessie Town during the time of the study were included.

Exclusion criteria

Participants who were severely ill and unable to communicate during data collection time were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

Sample size determination

To calculate the maximum estimated sample size, single population proportion formula was used at 95% CI and 5% marginal error and by taking the P-value of 59.2% from the previous study in Mekelle town residents [13]. Then the sample size was calculated as follows.

Where: n = sample size = prevalence of previous study (59.2%), d = degree of precision (assumed to be 5%), (z α/2)2 = 1.96,confidence levels at (95%).

Since we have employed a multi-stage sampling technique, by considering the designing effect, the calculated sample size was multiplied by 1.5 to correct the sampling error. After all, by adding a 5% non-response rate, the final sample size was 584.

Sampling technique and procedure

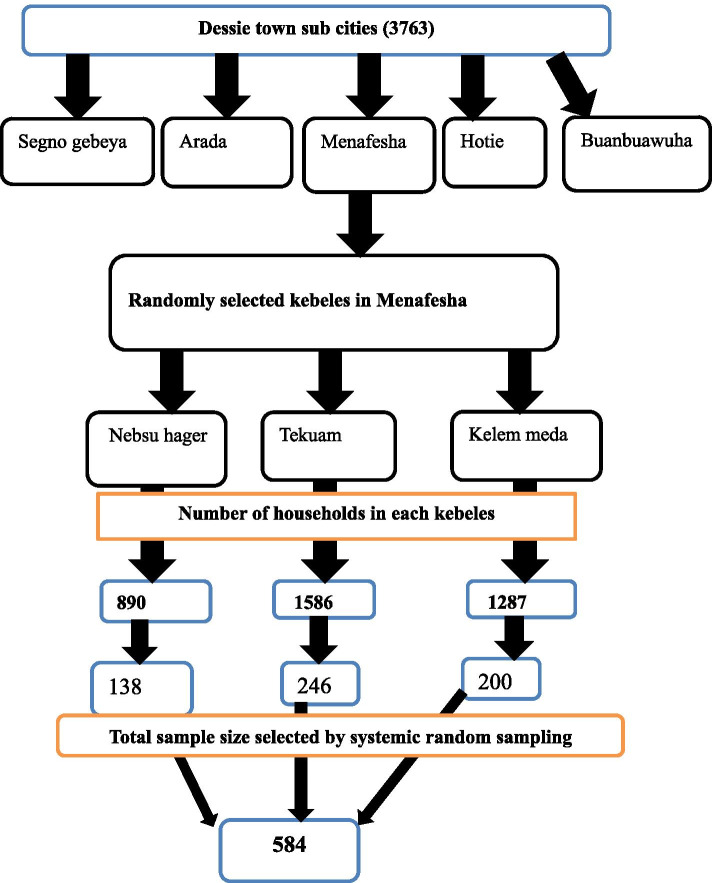

A multi-stage probability sampling technique was employed. There are five sub-cities in Dessie town, and one sub-town was selected from the total, using a simple random sampling technique, then within this chosen sub-town there are three kebeles, and the numbers of participants were selected from each kebele using the proportional allocation of the sample size. Then, a systematic random sampling technique was employed to select study units. The first study unit was selected randomly between 1st and Kth then study subjects were selected in every Kth household. When more than one study subject was found in one household, a lottery method was used to select a participant. If the selected house is closed during data collection, the next household participants were interviewed. i.e. Kj = Nj/nj Where Kj = sampling interval, Nj = total number of households, nj = total number of sample size. There are three kebeles in the Menafesha sub-town and having a total of 3763 households, K or interval was determined by N/n (K = 3763/584 = 7). We were interviewed one individual from every 7 households (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

schematic representation of sampling technique showing the number of selected samples from each sub-city of Dessie town, 2020 G.C

Data collection method and technique

Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. It includes socio-demographic variables, clinical variables, psychosocial factors, and outcome variables are knowledge and attitude towards mental illness. The Mental Health Knowledge Schedule MAKS (6 items) is a standardized instrument adapted and used for this study to assessing knowledge of the mental illness. The five-point scale was used to show total disagreement (scale = 1) and strong agreement (scale = 5). Better mental health literacy was shown by higher scores [31]. To determine the knowledge toward mental illness, similar to another study it became dichotomized [18]. For the cut point, we categorized the knowledge of those respondents with a mean value of 20.23 (poor knowledge < 20.23). In this study, the Cronbach α of the MAKS items was showed 0.71.

Attitudes towards mental illness are measured by the Community Attitude to Mental Illness Inventory (CAMI). It has 4 items with four sub-scales which are authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness, and community mental health ideology. All items are rated according to a 5 Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). It has been used in various countries of Africa including Ethiopia [29]. We categorized respondents as with favorable and unfavorable attitudes based on the mean score which was 117 (Good < 117). Social support was assessed by the Oslo social support 3 item questions with three categories; a score of 3–8 is poor social support, moderate social support 9–11, and strong social support 12–14 [32].

Data quality control

The questionnaire was prepared first in English and translated into the Amharic language then back-translated to English to check the consistency. Furthermore, we use standard tools to determine the outcome variable by giving 2 days of training for data collectors and supervisors. The pre-test was conducted with 5% (n = 28) of the participants in the Buanbuha sub-Town to identify potential problems in data collection tools and modification of the questionnaire. Regular supervision and support were given for data collectors by the supervisor and principal investigator. Data were checked for completeness and consistency by supervisors and principal investigators daily during data collection time for its completeness.

Data processing and analysis

The data was entered into the Epi-Data version 3.1, and then data was exported to SPSS 25.0 version for cleaning and analysis. Descriptive statistics: means, frequency, percentages, and standard deviations were calculated and presented in tables and graphs. Independent predictors were determined using logistic regression modeling. All variables p-value < 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. The model of fitness was checked by Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the strength of the association was measured by an odds ratio of 95% C.I.

Results

Socio-demographic distribution of the participants

This study intended to be included 584 households, despite 477 participated in the study which makes the response rate of 81.67%. The mean age (±SD) of the respondents was 36.26 (±11.7) years, with an age range of 18–70 years. From the total participants, the majority 257(53.9%) were male. The largest proportion of the participants were married 284 (59.5%), Amhara 470 (98.5%), and Muslim 358 (75.1%) in their respective domains. Besides, nearly one third of the participants were merchants 160 (33.5%). . More than half of 268 (56.2%) participants reported that their average monthly income was >=2166 Ethiopian birr (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic factors of Dessie town residents, Ethiopia, 2020 (N = 477)

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 18–24 | 81 | 17.0 |

| 25–34 | 173 | 36.3 | |

| 35–44 | 134 | 28.1 | |

| > 44 | 89 | 18.6 | |

| Sex | Male | 257 | 53.9 |

| Female | 220 | 46.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 284 | 59.5 |

| Single | 139 | 29.1 | |

| Widowed | 33 | 6.9 | |

| Divorced | 21 | 4.4 | |

| Ethinicity | Amhara | 470 | 98.5 |

| Othera | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 358 | 75.1 |

| Orthodox | 97 | 20.3 | |

| Protestant | 22 | 4.6 | |

| Level of education | Unable to read and write | 62 | 13.0 |

| Primary school | 73 | 15.3 | |

| Secondary school(9–12 grade) | 112 | 23.5 | |

| College diploma | 111 | 23.3 | |

| University degree and above | 119 | 24.9 | |

| Occupation | Government employee | 122 | 25.6 |

| Housewife | 78 | 16.4 | |

| Merchant | 160 | 33.5 | |

| Student | 71 | 14.9 | |

| Othersb | 46 | 9.6 | |

| Monthly income | < 2166 ETB | 209 | 43.8 |

| > = 2166 | 268 | 56.2 |

Othersa:-Oromo & Tigre, b:- Retired, NGOs & Farmer, ETB = Ethiopian birr

Source of information about mental health, clinical and psychosocial factors

Among the respondents, 252 (52.8%) had information about mental illness within the last year. Regarding the source of information, 126 (50%) of them were received from mass media. Of the study participants, 58 (12.2%) had a mental illness. All of the respondents know a mentally ill person through their life. Regarding their relationship knowing mentally ill person 106 (22.2%) were relatives, 142(29.8%) were neighbors, 58 (12.2%) were friends and 171(35.8%) of them were know with no relation. Out of the total participants, most of them, 305 (63.9%) respondents were never involved in caring for a person with a mental illness. Nearly one-third of participants 143 (30.0%) were threatened or hurt by a mentally ill person. Besides, 217 (45.5%) of residents witnessed others being hurt. The majority of the study participants 265 (55.6%) had received middle social support (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of information source about mental health, clinical and psychosocial related factors among Dessie town residents 2020 (N = 477)

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percent(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last 1 year, get information | Yes | 252 | 52.8 |

| No | 225 | 47.2 | |

| Source of information | Mass media | 126 | 50.0 |

| Health institution | 96 | 38.0 | |

| Religious institution | 30 | 12.0 | |

| Mental illness history | Yes | 58 | 12.2 |

| No | 419 | 87.8 | |

| Know somebody who has/had mental illness | Yes | 477 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Relationship to the person with mental illness | Relative | 106 | 22.2 |

| Neighbor | 142 | 29.8 | |

| Friends | 58 | 12.2 | |

| Person without relation | 171 | 35.8 | |

| Caring for a person with mental illness | Yes | 172 | 36.1 |

| No | 305 | 63.9 | |

| Threatened or get hurt by mental illness person | Yes | 143 | 30.0 |

| No | 334 | 70.0 | |

| Have you ever seen a mental health apprehension or abuse victim | Yes | 217 | 45.5 |

| No | 260 | 54.5 | |

| Social support | Poor social support | 100 | 21.0 |

| Moderate social support | 265 | 55.6 | |

| Strong social support | 112 | 23.5 |

Knowledge and attitude toward mental illness among Dessie town residents

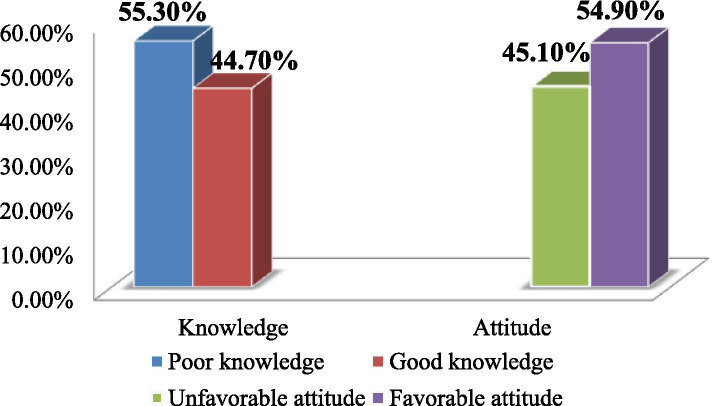

Regarding the overall magnitude of knowledge of participants towards mental illness, about 264 [55.3% (95% CI,50.9, 60.0)] had poor knowledge and 215 [45.1% (95% CI,40.7, 49.5)] had unfavorable attitudes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Magnitude of knowledge and attitude toward mental illness among Dessie town residents 2020 (N= 477)

Help-seeking behavior of the study participants

In this study, from the total respondents 454 (95.2%) of them believe that they will get help from an intimate partner if they were having a mental or emotional problem, 403(84.5%) from the neighborhood, 422(97.7%) from parents, 467(97.9) from relatives, 456(95.6%) from health workers, 409(85.7%) from religious leaders and 195(40.9%) from traditional healers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of help-seeking behavior among Dessie town residents 2020 (N = 477)

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate partner (husband,wife) | Likely | 454 | 95.2 |

| Unlikely | 23 | 4.8 | |

| Neighborhood/close friends | Likely | 403 | 84.5 |

| Unlikely | 74 | 15.5 | |

| Parents | Likely | 467 | 97.9 |

| Unlikely | 10 | 2.1 | |

| Another family member/relatives | Likely | 450 | 94.3 |

| Unlikely | 27 | 5.7 | |

| Health worker(e.g doctors, nurse, psychologist, counselor, social worker | Likely | 456 | 95.6 |

| Unlikely | 21 | 4.4 | |

| Religious leader | Likely | 409 | 85.7 |

| Unlikely | 68 | 14.3 | |

| Traditional healers | Likely | 195 | 40.9 |

| Unlikely | 282 | 59.1 |

Factors associated with knowledge status towards mental illness

Factors associated with poor knowledge in the bivariable analysis such as, age, sex, marital status, educational status, information about mental health, suffered from any mental illness, social support, and unfavorable attitude showed a p-value of < 0.25 and became candidates for multivariable analysis.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, respondents who are female sex, cannot read and write, lack of information about mental health, and have an unfavorable attitude towards mental illness were variables statistically associated with poor knowledge about mental illness at P-value less than 0.05. Accordingly, those being female [AOR = 1.62 (95% CI: 1.06,2.47)],who could not read and write [AOR = 6.28 (95% CI: 2.56, 15.39)], lack of information about mental [AOR = 5.82 (95% CI: 3.78,8.94)] and unfavorable attitude [AOR =1.73 (95% CI: 1.12,2.66)] were variables found statistical significant with poor knowledge towards mental illness (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis of associated factors for poor knowledge towards mental illness among Dessie residents, 2020

| Variables | Category | Knowledge | COR(95%C.I) | AOR(95%C.I) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | |||||

| Age | 18–24 | 52(64.2%) | 29(35.8%) | 1.22(0.65,2.26) | 2.08(0.99,4.37) | 0.052 |

| 25–34 | 84(48.6%) | 89(51.4%) | 0.64(0.38,1.07) | 0.92(0.49,1.74) | 0.811 | |

| 35–44 | 75(56.0%) | 59(44.0%) | 0.86(0.50,1.48) | 0.98(0.51,1.89) | 0.953 | |

| > 44 | 53(59.6%) | 36(40.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sex | Female | 138(62.7%) | 82(37.3%) | 1.75(1.21,2.52) | 1.62(1.06,2.47) | 0.025 |

| Male | 126(49.0%) | 131(51.0%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 161(56.7%) | 123(43.3%) | 1.29(0.86,1.93) | 1.19(0.69,2.05) | 0.533 |

| Widowed | 20(60.6%) | 13(39.4%) | 1.55(0.70,3.28) | 1.47(0.53,4.10) | 0.457 | |

| Divorced | 13(61.9%) | 8(38.1%) | 1.60(0.62,4.11) | 1.36(0.44,4.22) | 0.587 | |

| Single | 70(50.4%) | 69(49.6%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 54(87.1%) | 8(12.9%) | 8.69(3.81,19.87) | 6.28(2.56,15.39) | < 0. 000 |

| Primary school | 45(61.6%) | 28(38.4%) | 2.07(1.14,3.75) | 1.73(0.87,3.42) | 0.114 | |

| Secondary school [9–12] | 60(53.6%) | 52(46.4%) | 1.48(0.88,2.50) | 1.04(0.57,1.89) | 0.883 | |

| College diploma | 53(47.7%) | 58(52.3%) | 1.17(0.70,1.98) | 0.89(0.49,1.62) | 0.703 | |

| University degree and above | 52(43.7%) | 67(56.3%) | 1 | |||

| Any information about mental health | No | 172(76.4%) | 53(23.6%) | 5.644(3.78,8.43) | 5.82(3.78,8.94) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 92(36.5%) | 160(63.5%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Suffered from any mental illness | No | 237(56.6%) | 182(43.4%) | 0.55(0.27,1.13) | 1.36(0.72,2.59) | 0.345 |

| Yes | 27(46.6%) | 31(53.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social support | Poor social support | 63(63.0%) | 37(37.0%) | 2.11(1.22,3.66 | 1.63(0.84,3.14) | 0.143 |

| Moderate social support | 151(57.0%) | 114(43.0%) | 1.64(1.05,2.56) | 1.493(0.88,2.52) | 0.133 | |

| Strong social support | 50(44.6%) | 62(55.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attitude | Negative attitude | 135(62.8%) | 80(37.2%) | 1.74(1.21,2.51) | 1.73(1.12,2.66) | 0.013 |

| Positive attitude | 129(49.2%) | 133(50.8%) | 1 | |||

1 = reference category, Chi square = 8, Hosmer Lemeshow goodness-of-fit 0.56

Factors associated with unfavorable attitude towards mental illness among Dessie residents

In the bivariable analyses, marital status, income, suffered from any mental illness, social support, and knowledge showed a p-value of < 0.25 and became candidates for multivariable analysis. In multivariable binary logistic regression analyses, income, social support and poor knowledge were statistically associated with unfavorable attitude toward mental illness (Table 5).

Table 5.

Bivariable and multivariablelogistic regression analysis of associated factors for unfavorable attitude towards mental illness among Dessie Town residents, 2020

| Character | Attitude | COR(95%C.I) | AOR(95%C.I) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavorable | Favorable | |||||

| Marital status | Married | 130(45.8%) | 154(54.2%) | 1.18(0.78,1.77) | 1.45(0.93,2.26) | 0.102 |

| Widowed | 15(45.5%) | 18(54.5%) | 1.16(0.54,2.50) | 1.18(0.53,2.63) | 0.679 | |

| Divorced | 12(57.1%) | 9(42.9%) | 1.86(0.73,4.71) | 1.87(0.71,4.95) | 0.202 | |

| Single | 58(41.7%) | 81(58.3%) | 1 | |||

| Income | < 2166 | 110(52.6%) | 99(47.4%) | 1.72(1.19,2.48) | 1.64(1.12,2.41) | 0.011 |

| > = 2166 | 105(39.2%) | 163(60.8%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Suffered from any mental illness | Yes | 32(55.2%) | 26(44.8%) | 1.58(0.91,2.75) | 1.73(0.97,3.07) | 0.06 |

| No | 183(43.7%) | 236(56.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social support | Poor social support | 50(50.0%) | 50(50.0%) | 2.61(1.47,4.62) | 2.04(1.13,3.68) | 0.018 |

| Moderate social support | 134(50.6%) | 131(49.4%) | 2.673(1.65,4.31) | 2.44,1.45,3.97) | < 0.0001 | |

| Strong social support | 31(27.7%) | 81(72.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Knowledge | Poor knowledge | 135(51.1%) | 129(48.9%) | 1.74(1.20,2.51) | 1.66(1.13,2.43) | 0.009 |

| Good knowledge | 80(37.6%) | 133(62.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

1 = reference category, Chi square = 8, Hosmer Lemeshow goodness-of-fit 0.32

Discussion

Even if, the prevalence of mental illness growing rapidly in the world, especially in Dessie, Ethiopia, the knowledge, and attitude of people toward mental illness are not well addressed. Therefore, this study was intended to address this gap by assessing the knowledge and attitude towards mental illness in Dessie town residents in Ethiopia.

This study showed that about 55.3% of participants had poor knowledge and 45.1% had unfavorable attitudes towards mental illness. Regarding the level of poor knowledge, our result is in agreement with findings reported from Ethiopia 59.2% [13] and Nigeria 51.2% [11]. However, the prevalence in the current study is lower than the study conducted in Qatar 72.5% [8], Tanzania 85.9% [10], Kinondoni community 61% [3], Saudi public 87.5% [9], and Moroccan 76% [12]. This discrepancy might be due to variation in used inclusion criteria, in the academic qualification of the study participants, study period, study design, sampling size, tools, socioeconomic, sociocultural, and demographic characteristics.

On the other hand, in this study, 45.1% of respondents had reported an unfavorable attitude. The result is in line with a study conducted in Jimma, Ethiopia 46.9% [33]. But it is higher than the study done in Nigeria, the majority (90.0%) had positive attitudes toward mental illness [11]. The finding in the current study was lower than the result reported from Qatar which showed that the prevalence of unfavorable attitude was 53.5% [8], Tanzania 58.9% [10], Kinondoni 79.6% [3], and Saudi public 54.5% [9]. This variation might be due to numerous factors including differences in the characteristics of study participants, geographical location, socio-cultural variation, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria used.

The second objective of our study was to identify factors associated with poor knowledge and unfavorable attitude. A respondent with female in sex 1.62 times more likely to have poor knowledge as compared with males and this was supported by a study done in Ethiopia [13], Qatar [8], and India [19]. The possible explanation might be men are more eager to visit a psychiatrist for their emotional problems which might increase knowledge, while women preferred a traditional healer. Females are more afraid than males to talk about their illness. Furthermore, men obtained more information than women from the media; women favored healthcare staff more than men did [19].

Participants who could not read and write were 6.28 more likely to have poor knowledge as compared with a university degree and above and this was supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia [13, 23, 24], Malaysia [18], and Kinondoni [3]. It suggests that individuals with lower education had poor knowledge relating to mental illness. The possible explanation could be that participants with lower education have less access to health information, or they have a lesser ability understanding of such information as a result of their lower education. Furthermore, as recognized by World Health Organization that less education leads to lesser openness about mental illness [3].

Lack of information about mental health 5.82 more likely to have poor knowledge as compared to those who have information about mental illness. This study was a similar study conducted at Hawasa [28]. Reported that exposure to PWMI and having mental health information reduces stigma against mental illness leading to an overestimation of their information level and resulting from inadequate delivery of information by the public [15, 16].

Another factor associated with poor knowledge was unfavorable attitude, which was 1.73 times more likely to have a poor knowledge toward mental illness than a favorable attitude. Negative attitudes result in impeding requiring knowledge, which leads to discrimination, victims of human dignity, prevent social participation, decrease self-esteem, instill feelings of shame and guilt [26].

Participants with income < 2166 ETB have 1.64 more likely to have unfavorable attitudes as compared to favorable attitudes. This might be related to some negative emotions posed by survival pressure over low-income earners might result in an unfavorable attitude. Also, people with lower socioeconomic status have been hypothesized to get negative social, psychological, and economic skills that against the effect of hardship which would keep the negative attitude. This finding is similar to the study reported in Ethiopia [23] and the Saudi public [9].

Participants with poor knowledge had 1.66 times more likely to have unfavorable attitudes as compared to favorable attitudes. This is supported by a study done in conducted in Dodoma Municipality, Tanzania. lack of knowledge towards MI is significantly associated with attitude towards persons with mental illness [10]. In this case, possessing less knowledge of mental illness that individuals would have less social distancing, less tolerance/support to community care, and more social restrictiveness towards people with mental illness. In Ethiopia, most people beliefs that mental illness is due to demonic possession, bewitchment by the evil spirit and ancestors’ spirits, this influence the attitude towards mental illness and practice associated with mental health problems [14]. Another reason such as cultural variances might also play a significant role in this process [34].

The participant with poor social support were 2.04 times and moderate social support 2.44 times more likely to have unfavorable attitudes as compared to strong social support. This is the supported study conducted in Ethiopia. An individual who has experienced low social support has a poor attitude toward mental illness [13].

Limitations

This study might lack the establishment of the temporal relationship between the dependent and independent variables, because of the cross-sectional nature of the study design. Furthermore, since it was collected by face-to-face interview method, it might prone to social desirability bias. Finally, it was conducted in only Dessie town the study population might not generalizable for other general populations.

Conclusion

The finding of this study showed that, the knowledge and attitude of the community were poor, due to, different factors, such as being female, who could not read and write, lack of information about mental illness, and unfavorable attitude. Whereas, income < 2166, poor social support, moderate social support, and poor knowledge were factors to unfavorable attitude towards mental illness. This showed that a strong need, of community education program to increase awareness regarding mental illness, to improve access to psychiatric care for mentally ill persons, decrease stigma and unfavorable attitude towards mental illness.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Ajusted Odds Ratio

- CAMI

Community Attitude Mental Illness

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CMHI

Community Mental Health Ideology

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- Epi-Data

Epidemiological Data

- GGFRC

Gilgel Gibe Field Research Center

- KA

Knowledge, Attitude

- MASK

MentalHealth Knowledge Schedule

- NGOs

Non-Governmental Organizations

- PWMI

People with Mental Illness

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- USA

United States of American

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

MB and TA contributed to conceptualizing the design, conducting, doing the analyses, writing up, and interpreted the outcome of the analyses. All authors participated in preparing and approving the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data can be accessed from the corresponding author with the email address (mengeshasun@gmail.com).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted after getting ethical clearance from Wollo University, College of medicine and health science, department of community and mental health nursing ethical committee. The respondents were informed about the aim of the study from the study participants before the data collection. The confidentiality and privacy of the respondents were maintained. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before undertaking the interview. Those who did not want to take part in the study were allowed not to participate or to withdraw from the study at any time they want.

The method was done based on the guild line of research protocol prepared by University of Wollo and following all the procedure accordingly, which helps us to meet the international research procedure and show the result of this study by publish on scientific journal.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mengesha Birkie, Email: mengeshasun@gmail.com.

Tamrat Anbesaw, Email: tamratanbesaw@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Marcus M, Yasamy M, Van Ommeren M, Chisholm D, Saxena S. A global public health concern. WHO Department of mental health and substance abuse. 2012. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadock BJ. Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chikomo JG. Knowledge and attitudes of the Kinondoni community towards mental illness. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consortium WWMHS Prevalence, severity and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Jama. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinman A. Mental health in low-income countries. Harvard Review Psychiatry. 1995;3(4):235–239. doi: 10.3109/10673229509017191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain N, Bevc I, Husain M, Chaudhry I, Atif N, Rahman A. Prevalence and social correlates of postnatal depression in a low income country. Archives Women's Mental Health. 2006;9(4):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bener A, Ghuloum S. Gender differences in the knowledge, attitude and practice towards mental health illness in a rapidly developing Arab society. Int J Social Psychiatry. 2011;57(5):480–486. doi: 10.1177/0020764010374415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abolfotouh MA, Almutairi AF, Almutairi Z, Salam M, Alhashem A, Adlan AA, et al. Attitudes toward mental illness, mentally ill persons, and help-seeking among the Saudi public and sociodemographic correlates. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:45–54. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S191676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benedicto M, Mndeme E, Mwakagile D, Mwansisya T. Community knowledge, attitudes and perception towards mental illness in Dodoma municipality, Tanzania. ARC J Public Health Community Med. 2016;1(3):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mojiminiyi I. Knowledge and attitude towards mental disorders among adults in an urban community in south-West Nigeria. Malawi Med J. 2020;32(2):87–94. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v32i2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadri N, Manoudi F, Berrada S, Moussaoui D. Stigma impact on Moroccan families of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatr. 2004;49(9):625–629. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebrekidan Abbay A, Tibebe Mulatu A, Azadi H. Community knowledge, perceived beliefs and associated factors of mental distress: a case study from northern Ethiopia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2423. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishaw M. Promoting traditional medicine in Ethiopia: a brief historical review of government policy. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90180-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdulahi H, Hailemariam D. ke, D. Burden of disease in Butajira, Sout Ethiopia WHO Bulletin 2001.

- 16.Mesfin A, Aboud F. Mental illness in Ethiopia: In Kloos H and Zein AZ. The ecology of health and diseases in Ethiopia. 1993:493–506.

- 17.Song LY, Chang LY, Shih CY, Lin CY, Yang MJ. Community attitudes towards the mentally ill: the results of a national survey of the Taiwanese population. Int J Social psychiatry. 2005;51(2):162–176. doi: 10.1177/0020764005056765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeap R, Low WY. Mental health knowledge, attitude and help-seeking tendency: a Malaysian context. Singap Med J. 2009;50(12):1169–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesh K. Knowledge and attitude of mental illness among general public of southern India. Natl J Community Med. 2011;2(1):175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannigan B. Mental health care in the community: an analysis of contemporary public attitudes towards, and public representations of, mental illness. J Ment Health. 1999;8(5):431–440. doi: 10.1080/09638239917148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadopoulos C. Stigma towards people with mental health problems: an individualism-collectivism cross-cultural comparison. Middlesex University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barke A, Nyarko S, Klecha D. The stigma of mental illness in southern Ghana: attitudes of the urban population and patients' views. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(11):1191–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girma E, Möller-Leimkühler AM, Müller N, Dehning S, Froeschl G, Tesfaye M. Public stigma against family members of people with mental illness: findings from the Gilgel gibe field research center (GGFRC), Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deribew A, Tamirat YS. How are mental health problems perceivedby a community in Agaro town? Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19(2):153–159. doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v19i2.9985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawood E, Modayfer O. Public attitude towards mental illness and mental health services in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Res Hum Soc Sci. 2016;6:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(5):396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habtamu K, Minaye A, Zeleke WA. Prevalence and associated factors of common mental disorders among Ethiopian migrant returnees from the Middle East and South Africa. BMC psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1310-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayano G, Agidew M, Duko B, Mulat H, Alemayew M. Perception, attitude and associated factors on schizophrenia and depression among residents of Hawassa City, South Ethiopia, cross sectional study. Am J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;3(6):116. doi: 10.11648/j.ajpn.20150306.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeshanew B, Yohannis Z, Shumet S, Abebaw D, Belete A. Attitude and its’ associated factors towards mental illness among residents of Mertule Mariam town. Northern Ethiopia: Mixed Method; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunduma G, Girma M, Digaffe T, Weldegebreal F, Tola A. Prevalence and determinants of common mental illness among adult residents of Harari regional state, eastern Ethiopia. Pan African Med J. 2017;28(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Evans-Lacko S, Little K, Meltzer H, Rose D, Rhydderch D, Henderson C, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. Can J Psychiatr. 2010;55(7):440–448. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kocalevent R-D, Berg L, Beutel ME, Hinz A, Zenger M, Härter M, et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3) BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0249-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tesfaye Y, Agenagnew L, Terefe Tucho G, Anand S, Birhanu Z, Ahmed G, et al. Attitude and help-seeking behavior of the community towards mental health problems. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Picco L, Pang S, Shafie S, Vaingankar J, et al. Stigma towards people with mental disorders and its components–a perspective from multi-ethnic Singapore. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2017;26(4):371–382. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data can be accessed from the corresponding author with the email address (mengeshasun@gmail.com).