Abstract

JC virus (JCV) can cause a lytic infection of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) leading to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). JCV can also infect meningeal and choroid plexus cells causing JCV meningitis (JCVM). Whether JCV also infects meningeal and choroid plexus cells in PML patients and other immunosuppressed individuals with no overt symptoms of meningitis remains unknown. We therefore analyzed archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded brain samples from PML patients, and HIV-seropositive and seronegative control subjects by immunohistochemistry for the presence of JCV early regulatory T Ag and JCV VP1 late capsid protein. In meninges, we detected JCV T Ag in 11/48 (22.9%) and JCV VP1 protein in 8/48 (16.7%) PML patients. In choroid plexi, we detected JCV T Ag in 1/7 (14.2%) and JCV VP1 protein in 1/8 (12.5%) PML patients. Neither JCV TAg nor VP1 protein could be detected in meninges or choroid plexus of HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative control subjects without PML. In addition, examination of underlying cerebellar cortex of PML patients revealed JCV-infected cells in the molecular layer, including GAD 67+ interneurons, but not in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative control subjects without PML. Our findings suggest that productive JCV infection of meningeal cells and choroid plexus cells also occurs in PML patients without signs or symptoms of meningitis. The phenotypic characterization of JCV-infected neurons in the molecular layer deserves further study. This data provides new insight into JCV pathogenesis in the CNS.

Keywords: JCV, Meninges, Choroid plexus, PML

Introduction

The polyomavirus JC (JCV) is the etiologic agent of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an often fatal demyelinating disease of the CNS. JCV has a 5.13 kilobase (Kb) circular DNA genomic structure. Its coding region includes genes for the regulatory proteins (t and T Ag) and the capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3), as well as the agnoprotein. JCV primary infection is asymptomatic and the virus remains quiescent in healthy individuals without causing disease. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, JCV may reactivate and cause a lytic infection of cerebral oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, leading to PML (Gheuens et al. 2013).

We have shown that in addition to glial cells, JCV can also infect cerebellar granule cell neurons, cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons, and meningeal and choroid plexi cells, leading to JCV granule cell neuronopathy (JCV GCN), JCV encephalopathy (JCVE), and JCV meningitis (JCVM), respectively (Miskin and Koralnik 2015).

JCVM was initially described in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with fevers, headaches, and altered mental status, who had JCV DNA detected by polymerase chain reaction in the spinal fluid (Viallard et al. 2005). It was formally characterized as a productive, lytic infection of the meninges and choroid plexus cells in a hydrocephalic HIV-negative patient presenting with gait impairment, cognitive dysfunction, and urinary incontinence (Agnihotri et al. 2014). The incidence of JCVM is unknown because JCV PCR is not routinely tested in the CSF of patients with aseptic meningitis. However, there have been several cases where the diagnosis of JCVM was suspected based on rising titers of anti JCV-IgM (Blake et al. 1992), or because JCV was the only pathogen detected in the CSF of patients with meningeal symptoms (Ballesta et al. 2017). These patients had no parenchymal white matter lesions, cerebellar atrophy, or cortical abnormalities that would otherwise be expected with PML or other JCV-associated syndromes of JCV, and they occurred in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients.

Despite identification of a novel tropism for the epithelial cells of the meninges in JCVM, the prevalence of concomitant meningeal and choroid plexus JCV infection in patients with PML and other immunosuppressed individuals remains unknown. It is also unclear if JCVM can occur in combination with classical PML without any symptoms of meningitis. We sought to determine whether JCV infects meningeal (pia and arachnoid) and choroid plexus cells in PML patients with no overt symptoms of meningitis.

Methods

We analyzed formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) archival brain tissue from 48 PML patients (40 HIV-seropositive and 8 HIV-seronegative) as well as HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative control subjects for the presence of JC virus early regulatory TAg and JC virus late capsid protein VP1. We used immunohistochemistry (IHC), immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and electron microscopy (EM) techniques.

Immunohistochemistry staining

Archived paraffin-embedded patient tissue was cut, deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with the JCV-specific primary antibodies including anti-VP1 (PAB597; mouse) and anti-T Ag (SV40; rabbit). Secondary staining kits such as the mouse IgG and/or rabbit IgG Vectastain Elite ABC Kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were used to detect primary antibody, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence assay

Slides containing FFPE cerebellar samples were incubated in an oven for 2 h at 60 °C. Slides were immediately deparaffinized in xylene followed by rehydration through graded alcohols to dH20. For immunofluorescence staining, two types of antigen retrieval were employed. In an electric pressure cooker, the sections were heated for 15 min in Trilogy solution (cat. 920P, Cell Marque) and steamed for 20 min in Antigen Unmasking Solution (H-3300, Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-VP1 (1:100, PAB597), goat polyclonal anti-GAD67 (cat. ab80589, 1:100, Abcam), and rabbit polyclonal anti-MAP2 (cat.17490-1-AP 1:100, Proteintech). Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat (A11058), Alexa 647 donkey anti-mouse (A31571), and Alexa 488 donkey anti-rabbit (A21206) secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature.

Electron microscopy

Since no brain tissue was initially fixed for specifically for EM, following ABC/DAB immunohistochemistry, selected sections were processed for electron microscopy. Tissue was osmicated, “en bloc” stained using uranyl acetate, dehydrated in graded ethanol steps, infiltrated, and flat-embedded with Araldite 502 resin. Polymerized slivers of choroid plexus were dissected from the flat-embedded slices, re-embedded, and rotated orthogonally to the plane of sectioning. Sections were collected using a Leica UC6 ultra microtome and a diamond knife, followed by counterstaining in 5% aqueous uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate. Images were obtained using a Sigma HD VP scanning electron microscope in scanning-transmission (STEM) mode (Zeiss).

Results

In meningeal cells, we detected JCV T Ag in 11/48 (22.9%) and JCV VP1 protein in 8/48 (16.7%) PML patients. These included a total of 14 positive cases (29%), with 6 having T Ag alone, 3 VP1 alone, and 5 both T Ag and VP1 detection. Neither JCV T Ag nor VP1 protein was detected in the meninges of 26 HIV-seropositive and 17 HIV-seronegative control subjects without PML. In choroid plexus cells, we detected JCV infection in two cases, including JCV T Ag in 1/7 (14.2%) and JCV VP1 protein in 1/8 (12.5%) PML patients. Neither JCV T Ag nor VP1 protein was detected in choroid plexi of 2 HIV-seropositive and 12 HIV-seronegative control subjects without PML. Neither the patients with PML nor the controls had any signs or symptoms of meningitis. These data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detection of JCV large T Ag and capsid protein VP1 in meningeal and choroid plexus cells from PML patients and control subjects

| Meninges | JCV T Ag | JCV VP1 |

| N pos/N tested (%) | N pos/N tested (%) | |

| PML | 11/48 (22.9) | 8/48 (16.7) |

| HIV-positive controls | 0/26 (0) | 0/26 (0) |

| HIV-negative controls | 0/17 (0) | 0/17 (0) |

| Choroid plexus | JCV T Ag | JCV VP1 |

| N pos/N tested (%) | N pos/N tested (%) | |

| PML | 1/7 (14.2) | 1/8 (12.5) |

| HIV-positive controls | 0/2 (0) | 0/2 (0) |

| HIV-negative controls | 0/12 (0) | 0/12 (0) |

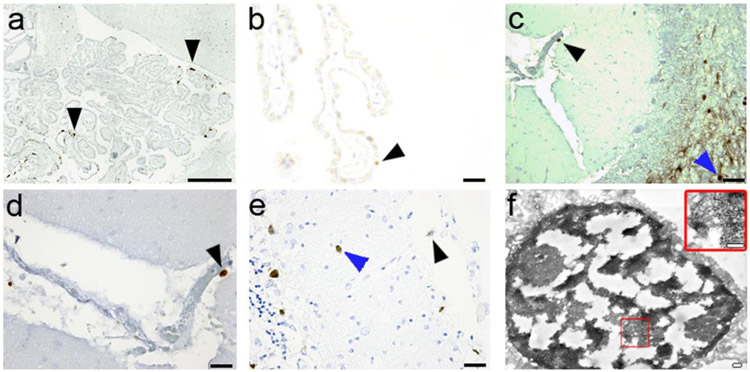

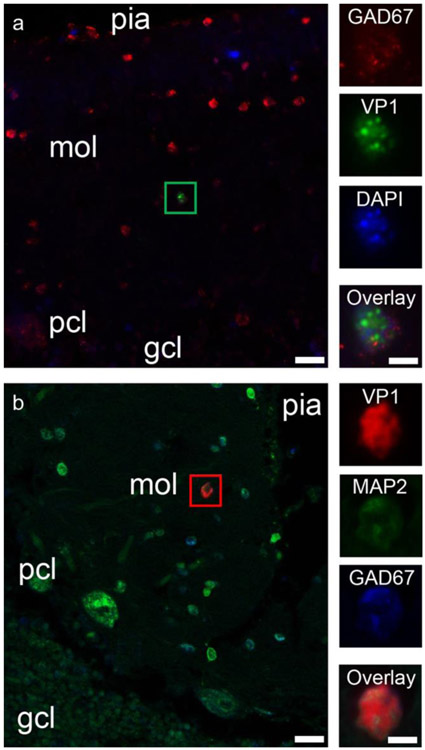

Representative examples of IC staining for JCV early regulatory TAg and JCV VP1 late capsid protein in meningeal and choroid plexus cells of PML patients are shown in Fig. 1. Electron microscopy analysis of a choroid plexus epithelial cell immunostained by JCV VP1 antibody revealed the presence of mature JC virions inside the nucleus (Fig. 1). Since all available samples studied for meningeal infection came from cerebellum, we also had the occasion to examine the underlying cerebellar molecular, Purkinje cell, and granule cell layers. As reported previously (Wuthrich et al., 2009), granule cells were observed to express JCV proteins. Notably, however, of 48 PML patients, 13 (27%) had JCV T Ag and 13 (27%) JCV VP1 expressing cells in the molecular layer, vs none of 26 HIV-seropositive and 5 HIV-seronegative control subjects. Triple immunofluorescence (IF) experiments revealed for the first time glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-67)-positive cerebellar cortical interneurons, expressing JCV VP1 in the molecular layer of a PML patient (GAD67+/DAPI+/VP1+) (Fig. 2a). To confirm our findings, additional triple IF experiments were repeated using antibodies against JCV VP1 and the neuronal marker MAP2 (MAP2+/VP1+/GAD67+; Fig. 2b). This is the first report of inhibitory neurons expressing JCV VP1 in the cerebellar molecular layer from a PML patient, indicative of a productive JCV infection in GABAergic neurons.

Fig. 1.

JCV infection in the meninges and choroid plexus in patients with PML. a JCV T Ag expression in the choroid plexus (arrows). Scale bar = 150 μm. b JCV T Ag expression in the choroid plexus indicating a restrictive infection (arrow). Scale bar = 20 μm. c JCV VP1 expression in the meninges (black arrow) demonstrating a productive JCV infection, with presence of JCV-infected cells in a PML lesion in the underlying cerebellar white matter (blue arrow). Scale bar = 20 μm. d higher magnification of the JCV-infected meningeal cell (black arrow) Scale bar =10 μm. e Concomitant productive JCV infection of the meninges (black arrow) and molecular cell layer of the cerebellum (blue arrow) staining for VP1. Scale bar = 20 μm. f Electron microscopy of choroid plexus containing JCV-infected epithelial cells. JCV VP1 immunoreactivity is demonstrated by electron-dense diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride bound to anti-VP1 antibody within the nucleus. Large amounts of 40 nm viral particles, consistent with the size of polyomaviruses, are present in the nucleus (inset). Scale bars = 200 nm

Fig. 2.

JCV infection of interneurons in the cerebellar molecular layer in PML patients. a JCV VP1 expression in an interneuron of the cerebellar molecular layer of a PML patient. Left—Double immunofluorescence image of the cerebellar cortex from a PML patient, shows numerous GAD-67-positive cerebellar cortical interneurons (red), one of which is also immunopositive for VP1 (noted with a green box). Pial surface of the cerebellar cortex is on the top of the image, with the molecular layer (mol), Purkinje cell layer (pcl), and granule cell layer (gcl) as indicated in the deeper layers. Scale bar = 20 μm. Right column—Higher magnification image of the interneuron marked with the green box. Panels show GAD67 immunopositivity (red), VP1 immunopositivity (green), nuclear staining (DAPI in blue), and then all three channels overlaid (Overlay). Scale bar = 5 μm. b JCV VP1 expression in an interneuron of the cerebellar molecular layer of a PML patient. Pial surface of the cerebellar cortex is on the top right of the image, with the molecular layer (mol), Purkinje cell layer (pcl), and granule cell layer (gcl) as indicated in the deeper layers. Scale bar = 20 μm. Right column—Higher magnification image of the interneuron marked with the green box. Panels show JCV VP1 immunopositivity (red), MAP2 immunopositivity (green), and GAD67 immunopositivity (red), and then all three channels overlaid (Overlay). Scale bar = 5 μm

Discussion

Infection of meningeal and choroid plexi cells

Our results demonstrate that concomitant JCV infection of the meninges and choroid plexus occurs in a subset of patients with PML. Productive infection of these cells is suggested by expression of the capsid protein VP1 indicating a full replication cycle, and production of mature viral particles demonstrated by EM. Of note, areas of cell loss in meninges and choroid plexus, which would confirm the spread of the virus, cannot be demonstrated in FFPE tissues due to the configuration of those structures. However, productive infection of primary meninges and choroid plexus cells was recently readily demonstrated in vitro (O’Hara et al. 2018). We did not detect any JCV infection of the meninges or choroid plexus in patients without PML regardless of their HIV status.

This is reminiscent of infection of granule cell neurons, which in isolation cause JCV GCN, but could also be found in up to 51% of patients with PML, irrespective of whether they have concomitant demyelinating lesions in white matter (Wuthrich et al. 2009). Similarly, JCV infection of cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons causes JCVE, but 50% PML patients also had infection of cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons. Furthermore, 11% of PML patients had cortical pyramidal neurons infected by JCV, in the absence of cortical and subcortical white matter lesions (Wuthrich and Koralnik 2012).

Infection of cells in the cerebellar molecular layer

Since all samples containing intact meninges came from cerebellar tissue, we had the opportunity to observe that JCV-infected cells were also present in the underlying molecular layer in a quarter of PML cases. Whether those cells are astrocytic or neuronal remains to be determined, since quantitative phenotypic analysis of those cells was beyond the scope of the present study. However, we confirmed that JCV may infect GABAergic interneurons in the molecular layer of the cerebellum.

Conclusions

There are limitations to our study. Meninges are frequently damaged during the post mortem extraction of the brain, and the meningeal surface on brain tissue sections is very small. We therefore focused our attention on cerebellar tissue, which had better preservation and more abundant meninges in the cerebellar folia, compared with the meningeal tissue available at the surface of the cerebrum. Furthermore, choroid plexi are frequently discarded at autopsy and only a limited number of samples were available to us for study.

Nevertheless, these data indicate that like cerebellar granule cell neurons and cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons, meningeal and choroid plexi cells can all be infected in patients with PML. This data provides new insight into JCV pathogenesis in the CNS. This suggests that JCV, in some instances, may first reach choroid plexi cells through the bloodstream. These cells may become infected and release JCV in the CSF, leading to infection of meningeal cells. JCV could use these cells as reservoirs. From there the virus may propagate to the underlying brain parenchyma, leading to infection of first neuronal and then glial cells. Indeed, we have observed that both cortical pyramidal and cerebellar granule cell neurons appeared to be the first parenchymal cells to be infected by JCV in absence of any underlying lesion of PML (Wuthrich et al. 2009; Wuthrich and Koralnik 2012). Whether detection of JCV in CSF could be a harbinger of PML in asymptomatic immunosuppressed individuals requires further study. Indeed, we found JCV DNA by PCR in the CSF of 2 of 27 (7.4%) natalizumab-treated MS patients who had no symptoms or MRI lesions consistent with PML. These individuals remained PML disease-free after discontinuation of natalizumab (Chalkias et al. 2014). Others reported JCV DNA in CSF of 2 of 200 natalizumab-treated MS patients without evidence of PML (Sadiq et al. 2010).

JCV DNA can be detected in rare instances in CSF of MS patients not on natalizumab (Iacobaeus et al. 2009; Alvarez-Lafuente et al. 2007) and of HIV-infected patients without PML (Koralnik et al. 1999).

Interestingly, choroid plexi were found to harbor JCV receptors that are required for attachment and entry of virions into susceptible cells (Haley et al. 2015). In addition, JCV can productively infect both primary human choroid plexus epithelial cells and meningeal cells in vitro. These studies suggest that JCV could use these cells as reservoirs for the subsequent invasion of brain parenchyma (O’Hara et al. 2018).

Funding information

This work was supported in part by a research grant from Biogen, and from NIH grants R01 NS074995 and NS047029 to IJK.

References

- Agnihotri SP, Wuthrich C, Dang X, Nauen D, Karimi R, Viscidi R, Bord E, Batson S, Troncoso J, Koralnik IJ (2014) A fatal case of JC virus meningitis presenting with hydrocephalus in a human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative patient. Ann Neurol 76(1):140–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Lafuente R, Garcia-Montojo M, De Las Heras V, Bartolome M, Arroyo R (2007) JC virus in cerebrospinal fluid samples of multiple sclerosis patients at the first demyelinating event. Mult Scler 13(5): 590–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesta B, Gonzalez H, Martin V, Ballesta JJ (2017) Fatal ruxolitinib-related JC virus meningitis. J Neuro-Oncol 23(5):783–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake K, Pillay D, Knowles W, Brown DW, Griffiths PD, Taylor B (1992) JC virus associated meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent girl. Arch Dis Child 67(7):956–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalkias S, Dang X, Bord E, Stein MC, Kinkel RP, Sloane JA, Donnelly M, Ionete C, Houtchens MK, Buckle GJ, Batson S, Koralnik IJ (2014) JC virus reactivation during prolonged natalizumab monotherapy for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 75(6):925–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheuens S, Wuthrich C, Koralnik IJ (2013) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: why gray and white matter. Annu Rev Pathol 8:189–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley SA, O’Hara BA, Nelson CD, Brittingham FL, Henriksen KJ, Stopa EG, Atwood WJ (2015) Human polyomavirus receptor distribution in brain parenchyma contrasts with receptor distribution in kidney and choroid plexus. Am J Pathol 185(8):2246–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobaeus E, Ryschkewitsch C, Gravell M (2009) Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and cerebrospinal fluid cells from patients with multiple sclerosis for detection of JC virus DNA. Mult Scler 15(1):28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, Lord CI, Letvin NI (1999) JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology 52(2):253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskin DP, Koralnik IJ (2015) Novel syndromes associated with JC virus infection of neurons and meningeal cells: no longer a gray area. Curr Opin Neurol 28(3):288–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara BA, Gee GV, Atwood WJ, Haley SA (2018) Susceptibility of primary human choroid plexus and epithelial cells and meningeal cells to infection by JC virus. J Virol 92(8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq SA, Puccio LM, Brydon EW (2010) JCV detection in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. J Neurol 257(6):954–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viallard JF, Ellie E, Lazaro E, Lafon ME, Pellegrin JL (2005) JC virus meningitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 14(12):964–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich C, Cheng YM, Joseph JT, Kesari S, Beckwith C, Stopa E, Bell JE, Koralnik IJ (2009) Frequent infection of cerebellar granule cell neurons by polyomavirus JC in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68(1):15–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich C, Koralnik IJ (2012) Frequent infection of cortical neurons by JC virus in patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71(1):54–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]