Abstract

Background

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis resulting from the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in and around joints. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to treat acute gout. This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2014.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (including cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors (COXIBs)) for acute gout.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, and Embase for studies to 28 August 2020. We applied no date or language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing NSAIDs with placebo or another therapy for acute gout. Major outcomes were pain, inflammation, function, participant‐reported global assessment, quality of life, withdrawals due to adverse events, and total adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included in this update 28 trials (3406 participants), including 5 new trials. One trial (30 participants) compared NSAIDs to placebo, 6 (1244 participants) compared non‐selective NSAIDs to selective cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors (COXIBs), 5 (712 participants) compared NSAIDs to glucocorticoids, 13 compared one NSAID to another NSAID (633 participants), and single trials compared NSAIDs to rilonacept (225 participants), acupuncture (163 participants), and colchicine (399 participants). Most trials were at risk of selection, performance, and detection biases.

We report numerical data for the primary comparison NSAIDs versus placebo and brief results for the two comparisons ‐ NSAIDs versus COX‐2 inhibitors and NSAIDs versus glucocorticoids.

Low‐certainty evidence (downgraded for bias and imprecision) from 1 trial (30 participants) shows NSAIDs compared to placebo. More participants (11/15) may have a 50% reduction in pain at 24 hours with NSAIDs than with placebo (4/15) (risk ratio (RR) 2.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 6.7), with absolute improvement of 47% (3.5% more to 152.5% more). NSAIDs may have little to no effect on inflammation (swelling) after four days (13/15 participants taking NSAIDs versus 12/15 participants taking placebo; RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.5), with absolute improvement of 6.4% (16.8% fewer to 39.2% more). There may be little to no difference in function (4‐point scale; 1 = complete resolution) at 24 hours (4/15 participants taking NSAIDs versus 1/15 participants taking placebo; RR 4.0, 95% CI 0.5 to 31.7), with absolute improvement of 20% (3.3% fewer to 204.9% more). NSAIDs may result in little to no difference in withdrawals due to adverse events (0 events in both groups) or in total adverse events; two adverse events (nausea and polyuria) were reported in the placebo group (RR 0.2, 95% CI 0.0, 3.8), with absolute difference of 10.7% more (13.2% fewer to 38% more). Treatment success and health‐related quality of life were not measured.

Moderate‐certainty evidence (downgraded for bias) from 6 trials (1244 participants) shows non‐selective NSAIDs compared to selective COX‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs). Non‐selective NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in pain (mean difference (MD) 0.03, 95% CI 0.07 lower to 0.14 higher), swelling (MD 0.08, 95% CI 0.07 lower to 0.22 higher), treatment success (MD 0.08, 95% CI 0.04 lower to 0.2 higher), or quality of life (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐6.7 to 6.3) compared to COXIBs. Low‐certainty evidence (downgraded for bias and imprecision) suggests no difference in function (MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.25) between groups. Non‐selective NSAIDs probably increase withdrawals due to adverse events (RR 2.3, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.1) and total adverse events (mainly gastrointestinal) (RR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.8).

Moderate‐certainty evidence (downgraded for bias) based on 5 trials (712 participants) shows NSAIDs compared to glucocorticoids. NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in pain (MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐2.7 to 3.0), inflammation (MD 0.3, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.6), function (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐2.2 to 1.8), or treatment success (RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.2). There was no difference in withdrawals due to adverse events with NSAIDs compared to glucocorticoids (RR 2.8, 95% CI 0.5 to 14.2). There was a decrease in total adverse events with glucocorticoids compared to NSAIDs (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.5).

Authors' conclusions

Low‐certainty evidence from 1 placebo‐controlled trial suggests that NSAIDs may improve pain at 24 hours and may have little to no effect on function, inflammation, or adverse events for treatment of acute gout. Moderate‐certainty evidence shows that COXIBs and non‐selective NSAIDs are probably equally beneficial with regards to improvement in pain, function, inflammation, and treatment success, although non‐selective NSAIDs probably increase withdrawals due to adverse events and total adverse events. Moderate‐certainty evidence shows that systemic glucocorticoids and NSAIDs probably are equally beneficial in terms of pain relief, improvement in function, and treatment success. Withdrawals due to adverse events were also similar between groups, but NSAIDs probably result in more total adverse events. Low‐certainty evidence suggests no difference in inflammation between groups. Only low‐certainty evidence was available for the comparisons NSAID versus rilonacept and NSAID versus acupuncture from single trials, or one NSAID versus another NSAID, which also included many NSAIDs that are no longer in clinical use. Although these data were insufficient to support firm conclusions, they do not conflict with clinical guideline recommendations based upon evidence from observational studies, findings for other inflammatory arthritis, and expert consensus, all of which support the use of NSAIDs for acute gout.

Plain language summary

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for acute gout

What is an acute gout flare, and what are NSAIDs?

Gout results from the deposition of monosodium urate crystals within and around joints and presents usually as self‐limited episodes of acute arthritis.

NSAIDs (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs) are drugs that reduce pain and inflammation but may increase the risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding. Cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 selective inhibitors (COXIBs) are a subgroup of NSAIDs that lead to fewer stomach ulcers.

Study characteristics

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2014 and updated on 28 August 2020, which revealed 28 trials (3406 participants). Most participants were men (69% to 100%) aged 44 to 66 years, with acute gout lasting less than 48 hours.

One trial (30 participants) compared placebo to an NSAID, 13 trials (518 participants) compared an NSAID to another NSAID, 6 trials (1244 participants) compared NSAIDs to COXIBs, 5 trials (772 participants) compared glucocorticoids to NSAIDs, 1 trial compared interleukin‐1 inhibitors to NSAIDs (225 participants), 1 trial compared acupuncture plus infrared irradiation to NSAIDs (163 participants), and 1 trial compared colchicine to NSAIDs (399 participants). We present key results for the primary comparison, NSAIDs versus placebo, as follows.

Key results

NSAID versus placebo

Pain improvement by more than 50% after 24 hours

47 more people out of 100 who took NSAIDs reported more than 50% improvement in pain compared to those given placebo

‐ 73 people out of 100 who took NSAIDs reported more than 50% improvement in pain

‐ 26 people out of 100 who took placebo reported more than 50% improvement in pain

Swelling improvement by more than 50% after 24 hours

6 more people out of 100 who took NSAIDs had more than 50% improvement in swelling compared to those given placebo

‐ 86 people out of 100 who took NSAIDs reported more than 50% improvement in swelling

‐ 80 people out of 100 who took placebo reported more than 50% improvement in swelling

Function improvement at 24 hours

20 more people out of 100 who took NSAIDs had improvement in function compared to those given placebo

‐ 27 people out of 100 who took NSAIDs reported improvement in function

‐ 7 people out of 100 who took placebo reported improvement in function

Side effects

10 fewer people out of 100 who took NSAIDs reported side effects compared to those given placebo

‐ 3 people out of 100 who took NSAIDs had side effects

‐ 13 people out of 100 who took placebo had side effects

There were no withdrawals due to side effects.

Quality of the evidence

Low‐certainty evidence from 1 study suggests that NSAIDs may improve pain after 24 hours compared to placebo.

Moderate‐certainty evidence shows that NSAIDs probably were equal to COXIBs in reducing pain and inflammation but with more side effects, and NSAIDs probably are equally beneficial as glucocorticoids with regards to pain but are probably less beneficial with regards to swelling, with more side effects. Only low‐certainty evidence from single trials was available for the comparisons NSAID versus rilonacept and NSAID versus acupuncture, or one NSAID versus another NSAID, which included NSAIDs no longer in use.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. NSAIDs compared to placebo for acute gout.

| NSAIDs compared to placebo for acute gout | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute gout Setting: Department of Rheumatology and Immunology of a general hospital Intervention: NSAIDs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without NSAIDs | With NSAIDs | Difference | ||||

| Pain: ≥ 50% improvement in pain (spontaneous pain at 24 hours) assessed with a 4‐point scale, 1 = no pain to 4 = worst pain Follow‐up: mean 11 days №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | RR 2.75 (1.13 to 6.72) | 26.7% | 73.3% (30.1 to 100) | 46.7% more (3.5 more to 152.5 more) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | Clinically important difference. Absolute change 47% more (3.5% more to 152.5% more) with NSAIDs. NNTB 3 (95% CI 2 to 12). NSAIDs may result in a decrease in pain (higher proportion of patients achieving ≥ 50% improvement in pain) |

| Inflammation: swelling assessed with a 4‐point scale, 1 = complete resolution to 4 = increase in inflammation at 4 days Follow‐up: mean 11 days №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) |

RR 1.08 (0.79 to 1.49) | 80.0% | 86.4% (63.2 to 100) | 6.4% more (16.8 fewer to 39.2 more) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | The difference is not statistically significant (95% CI includes both improvement in swelling and no improvement). Absolute change 6.4% more patients (16.8% fewer to 39.2% more). NSAIDs may have no effect on inflammation (swelling) |

| Function: ≥ 50% improvement in pain with movement at 24 hours assessed with a 4‐point scale, 1 = complete resolution to 4 = increase in pain intensity Follow‐up: mean 11 days №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | RR 4.00 (0.50 to 31.74) | 6.7% | 26.7% (3.3 to 100) | 20.0% more (3.3 fewer to 204.9 more) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | The difference is not statistically significant (95% CI includes both improvement in function and no improvement). Absolute change 20% more (3.3% fewer to 204.9% more). NSAIDs may have no effect on function (pain with movement) |

| Participants' global assessment of treatment: not measured №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | not estimable | 0.0% | 0.0% (0 to 0) | 0.0% fewer (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | No studies measured the outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life: not measured №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | not estimable | 0.0% | 0.0% (0 to 0) | 0.0% fewer (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | No studies measured the outcome |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events assessed with reported withdrawals Follow‐up: mean 11 days №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | not estimable | 0.0% | 0.0% (0 to 0) | 0.0% fewer (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb | No events reported in both groups; NSAIDs may have no effect on withdrawals due to adverse events |

| Total adverse events assessed with reported adverse events Follow‐up: mean 11 days №. of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | RR 0.20 (0.01 to 3.85) | 13.3% | 2.7% (0.1 to 51.3) | 10.6% fewer (13.2 fewer to 38 more) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | Evidence suggests that NSAIDs result in little to no difference in adverse events. The difference is not statistically significant (95% confidence intervals include both an increase and a decrease in adverse events). Absolute change 10.6% fewer (13.2% fewer to 38% more) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aTrial at unclear risk of selection bias and reporting bias, hence downgraded for bias.

bEvidence from one small trial (30 participants) with wide confidence intervals, downgraded for imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Non‐selective NSAIDs versus selective cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibitors.

| NSAIDs compared to cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs) for acute gout | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute gout Setting: hospital Intervention: NSAIDs Comparison: cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without NSAIDs | With NSAIDs | Difference | ||||

| Pain: mean change from baseline on 5‐point (0 to 4, 0 no pain) Likert scale Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 1044 (6 RCTs) | ‐ | Mean change in pain from baseline without NSAIDs was 1.99 points | Mean change in pain from baseline with NSAIDs was 2.02 points | MD 0.03 points higher (0.07 lower to 0.14 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in mean change from baseline pain compared to COXIBs |

| Inflammation (swelling): mean change from baseline on 4‐point (0 to 3, 0 no swelling) Likert scale Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 1044 (6 RCTs) | ‐ | Mean change in inflammation from baseline without NSAIDs was 1.92 points | Mean change in inflammation from baseline with NSAIDs was 2 points | MD 0.08 points higher (0.07 lower to 0.22 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in inflammation (swelling). The 95% confidence intervals included both an increase and a decrease in swelling |

| Function: mean change in pain with movement from baseline on 4‐point (0 to 3, 0 best function) Likert scale Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 91 (1 RCT) | ‐ | Mean change in function from baseline without NSAIDs was 0 | Mean change in function from baseline with NSAIDs was 0.04 | MD 0.04 higher (0.17 lower to 0.25 higher) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | NSAIDs may result in little to no difference in function. The 95% confidence intervals included both an improvement and a reduction in function |

| Participants' global assessment of treatment success on 5‐point (0 very good) Likert scale Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 730 (4 RCTs) | ‐ | Mean participant's global assessment of treatment success without NSAIDs was 1.36 points | Mean participant's global assessment of treatment success with NSAIDs was 1.44 points | MD 0.08 points higher (0.04 lower to 0.21 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably do not increase participants' global assessment of treatment success. The 95% confidence intervals include both treatment success and no success |

| Health‐related quality of life on SF‐36 (mental health component) Scale from 0 to 100 (0 worst quality of life) Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 222 (1 RCT) | ‐ | Mean health‐related quality of life without NSAIDs was 51.11 points | Mean health‐related quality of life with NSAIDs was 50.93 points | MD 0.18 point lower (6.7 lower to 6.34 higher) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | NSAIDs may result in little to no difference in health‐related quality of life. The 95% confidence intervals include both improvement and no improvement in quality of life |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 1243 (6 RCTs) | RR 2.34 (1.33 to 4.14) | 2.9% | 6.7% (3.8 to 11.9) | 3.9% more (1 more to 9 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably increase withdrawals due to adverse events. Absolute change 4% more (1% more to 9% more). NNTH 26 (NNTH 11 to 105)c |

| Total adverse events Follow‐up: 7 days №. of participants: 1232 (6 RCTs) | RR 1.94 (1.36 to 2.78) | 23.1% | 44.8% (31.4 to 64.2) | 21.7% more (8.3 more to 41.1 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably increase adverse events. Absolute change 22% more (8% more to 41% more). NNTH 5 (NNTH 3 to 13)c |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SF‐36: 36‐Item Short Form questionnaire. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aXu 2016 was at high risk of bias regarding blinding of participants and personnel; Rubin 2004 and Willburger 2007 had unclear risk of bias for these domains. In three trials (Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007), the role of funding by the pharmaceutical industry might have biased the results. Only 1 out of 6 trials was at low risk of bias (Li 2013).

bNumber needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) = n/a when result is not statistically significant. NNT for dichotomous data was calculated using Cates NNT calculator (http://www.nntonline.net/ebm/visualrx/help.asp).

cEvidence from one single trial with a small number of participants (45 in each arm), downgraded for imprecision.

Summary of findings 3. NSAIDs compared to glucocorticoids for acute gout.

| NSAIDs compared to glucocorticoids for acute gout | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute gout Setting: hospital Intervention: NSAIDs Comparison: glucocorticoids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without NSAIDs | With NSAIDs | Difference | ||||

| Pain: mean decrease per hour on a VAS scale (0 to 100, 0 no pain) Follow‐up: mean 7 days №. of participants: 584 (3 RCTs) | ‐ | Mean pain without NSAIDs was 18.8 points | Mean pain without NSAIDs was 18.95 points | MD 0.15 points higher (2.71 lower to 3.02 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in mean pain reduction on visual analogue scale per 1 to 6 hours. The 95% confidence intervals include both a reduction and an increase in pain |

| Inflammation: swelling mean difference in change from baseline to 14 days assessed with 4‐point Likert scale from 0 (no inflammation) to 3 (bulging beyond margin) Follow‐up: mean 14 days №. of participants: 69 (1 RCT) | ‐ | Mean change in swelling without NSAIDs was 0 | Mean change in swelling with NSAIDs was 0.33 | MD 0.33 higher (0.07 higher to 0.59 higher) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | NSAIDs may result in little to no difference in inflammation (swelling) |

| Function: walking disability during first 6 hours assessed with 0 to 100 VAS scale ‐ 0, no disability Follow‐up: mean 7 days №. of participants: 485 (2 RCTs) | ‐ | Mean function: walking disability without NSAIDs was 70 points | Mean function: walking disability with NSAIDs was 70.21 points | MD 0.21 points lower (2.22 lower to 1.8 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in function. The 95% confidence intervals include both a reduction and an increase in function |

| Patients' global assessment of treatment success at day 3 to 4 assessed with 5‐point Likert scale Follow‐up: mean 4 days №. of participants: 129 (2 RCTs) | RR 0.92 (0.70 to 1.22) | 69.8% | 78.2% (64.3 to 95.7) | 8.4% more (5.6 fewer to 25.8 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in treatment success; 95% confidence intervals include both an increase and a decrease in the proportions of those reporting treatment success. Absolute change 8.4% more (5.6% fewer to 25.8% more). NNTB n/ac |

| Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) Not reported | not estimable | 0.0% | 0.0% (0 to 0) | 0.0% fewer (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ‐ | Not assessed |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events Follow‐up: mean 7 days №. of participants: 772 (5 RCTs) | RR 2.80 (0.55 to 14.22) | 0.8% | 2.2% (0.4 to 11.1) | 1.4% more (0.4 fewer to 10.4 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in little to no difference in withdrawals due to adverse events. The 95% confidence intervals include both an increase and a decrease in proportions of withdrawals. Absolute change 1.4% more (0.4% fewer to 10.4% more). NNTH n/ac |

| Total adverse events Follow‐up: mean 7 days №. of participants: 753 (5 RCTs) | RR 1.62 (1.03 to 2.55) | 52.1% | 84.5% (53.7 to 100) | 32.3% more (1.6 more to 80.8 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | NSAIDs probably result in more total adverse events. Absolute change 32% more (1.6% more to 80.8% more). NNTH 5 (4 to 19)c |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aUnclear risk of bias for allocation concealment ‐ Janssens 2008a ‐ and for selective reporting ‐ Man 2007; Rainer 2016. Xu 2016 was at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel and had unclear risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment. Zhang 2014 had high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel and for blinding of outcomes assessment; random sequencing and allocation concealment were at unclear risk of bias.

bNumber needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) = n/a when result is not statistically significant. NNT for dichotomous data was calculated using Cates NNT calculator (http://www.nntonline.net/ebm/visualrx/help.asp) and for continuous data using the Wells calculator.

cEvidence from one single trial with a small number of participants (68 in both arms).

Background

Description of the condition

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis that is characterised by the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals within synovial fluid and other tissues. The natural history of articular gout is generally characterised by two different states: a preclinical state consisting of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and a clinical state of gout defined by the presence of flares, with or without tophi and bone erosions (Bursill 2019). Gout often heralds its presence by an exquisitely painful acute monoarthritic flare of sudden onset; oligoarticular and polyarticular flares are less common and often occur in patients with poorly controlled disease or during hospitalisation (Dalbeth 2021). Gout occurs in the backdrop of hyperuricaemia, which is necessary but not sufficient to cause gout (Dalbeth 2021). Hyperuricaemia itself is most commonly caused by insufficient secretion of uric acid, rarely by overproduction, and sometimes by both (Dalbeth 2021). Lower limb joints, particularly the big toe, are the most commonly involved, followed by the mid‐tarsal, ankle, knee, and upper limb joints. Subsequent acute flares tend to be longer lasting and polyarticular and tend to affect upper limb joints, such as wrist or elbow (Dalbeth 2021).

Description of the intervention

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors are commonly used to treat inflammatory conditions (Garner 2009; Garner 2010; Wienecke 2008). Published guidelines recommend their use for treating acute attacks, with maximum doses given for a short time (Jordan 2007; Khanna 2012; Zhang 2006). These guidelines state that all NSAIDs are equally effective.

How the intervention might work

NSAIDs inhibit inflammation by binding cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) enzymes. Evidence has shown that COX‐2 expression in monocytes is induced in response to MSU microcrystal formation (Pouliot 1998). Therefore, it is likely that NSAIDs exert their beneficial effects in gout by inhibiting the production of COX‐2‐mediated pro‐inflammatory prostaglandins. Most NSAIDs are non‐selective inhibitors; this means they inhibit both COX‐1 and COX‐2. Because non‐selective NSAIDs also act on COX‐1, they may decrease protective stomach prostaglandin levels, which explains the main adverse event of NSAIDs: ulcers and eventually bleeding. A newer class of NSAIDs are the COXIBs: they selectively inhibit COX‐2, which is not involved in the formation of prostaglandins for the stomach and, therefore, may have fewer adverse effects on the gastric mucosa; they are recommended for people at risk for development of ulcers. The main problem with the use of NSAIDs, including COXIBs, is the potential risk of cardiovascular and renal disease (Feenstra 2002; Kearney 2006; Marks 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Acute gout is an extremely painful condition that has a significant impact on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), as well as on productivity and ability to function (Rhody 2007; Singh 2006). Without treatment, flares resolve on average only after seven days (Bellamy 1987). Therefore, it is important to rapidly relieve the symptoms caused by acute gout. NSAIDs are known to be among the physician's first choice for treatment of acute gout, but due to potential adverse effects, their use is limited in people with comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, renal impairment, and a history of peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding (Borer 2005). The benefits and harms of NSAIDs in treating acute gout were systematically reviewed in 2014 (van Durme CMPG 2014); it is important to update this review to include relevant new evidence.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (including cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors (COXIBs)) for acute gout.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐randomised controlled clinical trials (CCTs) that compared NSAIDs to another therapy (active or placebo, including non‐pharmacological therapies) for acute gout. We included only trials that were published as full articles or were available as full trial reports.

Types of participants

We included studies of adults (aged 18 years or older) with a diagnosis of acute gout. We excluded populations that included a mix of people with acute gout and other musculoskeletal pain unless results for the acute gout population could be separately analysed.

Types of interventions

All trials that evaluated NSAIDs were included, other than those for NSAIDs that are no longer available (e.g. rofecoxib (trademark: Vioxx)).

Comparator treatments could be:

placebo;

no treatment;

paracetamol;

colchicine;

systemic or intra‐articular glucocorticoids;

interleukin‐1 (IL‐1) inhibitors;

non‐pharmacological treatments;

one NSAID versus another NSAID; or

combination therapy (any of the above in combination).

Types of outcome measures

For the purposes of this review, we included outcome measures that were considered to be of greatest importance to people with acute gout and the clinicians who care for them.

OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials) has proposed a set of recommended outcome measures to be used for evaluation of resolution of acute attacks (Grainger 2009; Schumacher 2009). Intense pain is the hallmark of an acute gout attack, hence pain has been proposed as an OMERACT outcome measure; it also has been a consistent outcome measure in clinical trials involving acute gouty arthritis, although the instruments and time intervals used to measure pain vary (Grainger 2009). Other proposed OMERACT outcome measures include joint swelling and tenderness, participant global assessment, and harms (Grainger 2009; Schumacher 2009).

It is recognised that interpreting the meaning of mean changes in continuous measures of pain (e.g. mean change on a 100‐mm visual analogue scale (VAS)) is hampered when participants report either very good or very poor pain relief (Moore 2010). For trials of interventions for chronic pain, the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) has recommended that dichotomous pain outcomes (the proportion of participants improved by 30% or greater and by 50% or greater) be reported (Dworkin 2008), although no recommendations have yet been published for acute pain. Therefore, we elected to include a dichotomous pain outcome measure (the proportion of participants reporting 30% or greater pain relief) as the primary benefit measure in this review. However, as most trials of interventions for acute gout report continuous measures, we included mean change in pain score as a secondary benefit measure.

Major outcomes

Pain: the proportion of participants who reported pain relief of 50% or greater; if not found, the following data were extracted: proportion of participants who achieved pain relief of 30% or greater, or proportion of participants achieving a pain score below 30/100 on VAS, or pain measured as a continuous outcome (e.g. VAS, numerical rating scale)

Inflammation (joint swelling, erythema, tenderness): if more than one measure was reported in an individual trial, we extracted only one according to the following hierarchy: swelling, erythema, and tenderness. We extracted data (when applicable) both for an index joint and for the total number of inflamed joints

Function of target joint (e.g. measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ))

Participants' global assessment of treatment success

HRQoL as reported by generic questionnaires (e.g. 36‐Item Short Form (SF‐36)) or by disease‐specific questionnaires (e.g. Gout Assessment Questionnaire (GAQ), Gout Impact Scale (GIS))

Study participant withdrawal due to adverse events (AEs)

Total number of adverse events

Minor outcomes

Serious adverse events

We planned to include outcomes at all time points measured in the included trials. We planned to pool available data into short‐term (up to two weeks), medium‐term (two to six weeks), and long‐term (more than six weeks) outcomes, but only short‐term data were available. When available, we chose to include the earliest time point for the outcome pain, swelling, and function, as this was more clinically relevant. For the other outcomes (participants' global assessment of treatment success and HRQoL), we chose the latest time point/end of treatment, as we also considered this to be more clinically relevant.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched a registry of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in gout, established by Cochrane Musculoskeletal to facilitate the updates of a series of reviews of interventions for gout, including this review update. The search for the gout registry was designed not to include terms for any interventions, to establish a registry of all randomised trials in this condition, regardless of the intervention. The following electronic databases were searched to establish the registry. The search strategy combined standard Cochrane search filters for 'gout' and 'randomised trial', with no language restrictions.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library, via Ovid, to 28 August 2020 (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE via Ovid, 1948 to 28 August 2020 (Appendix 2).

Embase via Ovid, 1980 to 28 August 2020 (Appendix 3).

We also searched the clinical trials register clinicaltrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) trials register for relevant trials, using the search term 'gout'. Details of search strategies used for the previous version of this review are given in van Durme CMPG 2014.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the bibliographies of all included papers for information on any other relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Editorial staff from Cochrane Musculoskeletal initially screened titles and abstracts in the gout registry and retrieved full texts for all records that they identified as RCTs of an intervention for people with gout. Editorial staff annotated the population, intervention, and comparator for each full‐text article and assigned it to the appropriate gout review. They imported relevant records to Covidence to select studies eligible for inclusion in this review update (www.covidence.org).

Two review authors (CD and MW) independently screened each title and abstract for suitability for inclusion in the review. They decided independently of each other upon the eligibility of each article according to the pre‐determined selection criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). If more information was required to establish whether inclusion criteria were met, we obtained the full text of the paper. We documented all reasons for excluding studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus after review of the full‐text article. A third review author (RL) resolved differences when necessary. We translated studies into English when necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CD and MW) independently extracted data from included trials, including study design, characteristics of the study population, treatment regimen and duration, relevant outcomes, timing of outcome assessment, and duration of follow‐up. We extracted data using a standardised form.

We extracted raw data (means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous outcomes, number of events or participants for dichotomous outcomes) for the outcome of interest. We resolved differences in data extraction by referring back to the original articles. When needed, we consulted a third review author (RL).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CD and MW) assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the methods recommended by Cochrane for the following items (Higgins 2017): random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, care provider, and outcome assessor for each outcome measure; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other sources of bias such as deviation from the study protocol in a way that did not reflect clinical practice, inappropriate administration of an intervention, presence of unequal co‐interventions, or funding by pharmacological industry.

We assessed these criteria as showing low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Review authors discussed disagreements at a consensus meeting. A third review author (RL) made the final decision when consensus could not be reached.

Measures of treatment effect

To assess benefit, we extracted, if available from published reports, raw data for outcomes of interest (means and SDs for continuous outcomes, numbers of events for dichotomous outcomes) as well as numbers of participants. If we needed to convert or impute reported data, we recorded this in the notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table. We plotted the results of each trial as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We planned to present point estimates as risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes and as mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes. An RR greater than 1.0 indicates a beneficial effect of NSAIDs (Deeks 2020). RRs are considered clinically relevant if the 95% CI is smaller than 0.7 in favour of the intervention, or larger than 1.5 in favour of the control. This resembles an absolute difference of 25%.

For continuous data, we analysed MD results between intervention and comparator groups, with corresponding 95% CIs. The MD between groups was weighted by the inverse of the variance in the pooled treatment estimate. However, if different scales were used to measure the same conceptual outcome (e.g. functional status, pain), we calculated standardised mean differences (SMD) instead, with corresponding 95% CIs. SMDs were calculated by dividing the MD by the SD, resulting in a unit‐less measure of treatment effect (Deeks 2020). SMDs greater than zero indicate a beneficial effect in favour of NSAIDs for management of symptoms in acute gout attacks. We computed a 95% CI for the SMD when needed. The SMD can be interpreted as described by Cohen (Cohen 1988), that is, an SMD of 0.2 is considered to indicate a small beneficial effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect of NSAIDs for management of symptoms in acute gout attacks. SMDs are considered to indicate a clinically relevant effect if they are larger than 0.5. Upon completion of the analysis, we had planned to translate the SMD back into an MD, using the control group SD at baseline to represent the population SD on a common scale (e.g. 0‐ to 10‐point pain scale), which can be better appraised by clinicians.

In the Effects of interventions section under Results and in the 'Comments' column of the 'Summary of findings' table, we provided the absolute percentage difference and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (NNTB or NNTH only for dichotomous outcomes with a clinically significant difference). For dichotomous outcomes, the absolute percentage change was calculated from the difference in risk between intervention and control groups using GRADEpro (GRADEpro 2015), expressed as a percentage. We calculated the NNTB or the NNTH from the control group event rate and the RR by using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2008).

Unit of analysis issues

We did not expect unit of analysis problems in this review. In the event that we had identified cross‐over trials in which reporting of continuous outcome data precluded paired analysis, we did not plan to include these data in a meta‐analysis, to avoid unit of analysis error. When carry‐over effects were thought to exist, and when sufficient data were found, we planned to include only data from the first period in the analysis (Higgins 2020a). When outcomes were reported at multiple follow‐up times, we planned to extract data at the following time points: short term (up to two weeks), medium term (more than two weeks to six weeks), and long term (more than six weeks). However, in the included trials, only short‐term outcomes were presented. If more than one time point was reported within the time frame (e.g. at one‐week follow‐up, at two‐week follow‐up), we planned to extract the later time point (i.e. two weeks).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors when important data were missing.

In case individuals were missing from reported results and no further information was forthcoming from the study authors, we assumed missing values to indicate a poor outcome. For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. number of withdrawals due to adverse events), we planned to calculate the withdrawal rate using the number of participants randomised in the group as the denominator (worst‐case analysis). For continuous outcomes (e.g. mean change in pain score), we planned to calculate the MD or the SMD based on the number of participants analysed at that time point. If the number of participants analysed was not presented for each time point, we planned to use the number of randomised participants in each group at baseline.

When possible, we computed missing SDs from other statistics such as standard errors, confidence intervals, or P values, according to the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2020). If we could not calculate SDs, we planned to impute them (e.g. from other studies in the meta‐analysis).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed studies for clinical homogeneity with respect to intervention groups (type of NSAID), control groups, timing of outcome assessment, and outcome measures. For any studies judged as clinically homogeneous, we planned to assess statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic based on the following approximate guide (Deeks 2020): 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity. In cases of considerable heterogeneity (defined as I² greater than 75%), we planned to explore the data further, including subgroup analyses, in an attempt to explain the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned an assessment of reporting biases through screening of the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the WHO to determine whether the protocol of the RCT had been published before study participant recruitment was started (DeAngelis 2004).

Furthermore, we planned a comparison between the fixed‐effect estimate and the random‐effects model (to assess the possible presence of small‐sample bias), as well as a funnel plot (to assess the possible presence of reporting bias), if data were available (Page 2020). However, data were insufficient to permit these analyses.

Data synthesis

If we considered studies sufficiently homogeneous, we pooled data in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model, irrespective of I² statistic results. We performed analyses using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2020), and we produced forest plots for all analyses for the following comparisons: NSAIDs versus placebo; non‐selective NSAIDs versus COXIBs; and NSAIDs versus glucocorticoids.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When sufficient data were available, we planned the following three subgroup analyses.

Disease severity (monoarticular versus polyarticular).

Presence or absence of comorbidities (such as cardiovascular or renal disease, history of peptic ulcer).

Duration of treatment: short term (up to two weeks) versus long term (longer than six weeks).

If trial data were available, we planned to extract major outcomes for the above subgroups within each trial (e.g. monoarticular versus polyarticular) and to informally compare the magnitude of effects between subgroups by assessing the overlap of CIs for the effect estimate (for the main benefit outcome only). Non‐overlap of CIs indicates statistically significant responses between subgroups. However, data were insufficient for any subgroup analyses to be performed.

Sensitivity analysis

When sufficient studies existed, we planned sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of any bias attributable to inadequate or unclear treatment allocation (including studies with quasi‐randomised designs) or to lack of blinding. However, data were insufficient for sensitivity analyses to be performed.

Interpreting results and reaching conclusions

We followed the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 15 (Schunemann 2020a), when interpreting results, and we were aware of distinguishing lack of evidence of effect from lack of effect. We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative synthesis of studies included in this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice; our implications for research suggest priorities for future research and outline remaining uncertainties in this area.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We produced 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2015). These tables include an overall grading of evidence based on the GRADE approach as recommended by Cochrane (Schünemann 2020). We produced a summary of available data on the following seven major outcomes: mean improvement in pain, reduction of inflammation measured by swelling, function of target joint, participant global assessment, HRQoL, number of withdrawals due to adverse events, and total adverse events. We have presented three SoF tables for the following comparisons: NSAIDs versus placebo; and two of the most clinically relevant comparisons with multiple trials that allowed pooling of outcomes (non‐selective NSAIDs versus COXIBs and NSAIDs versus glucocorticoids). We did not produce SoF tables for comparisons with single trials of only low‐certainty evidence (NSAID versus rilonacept, NSAID versus acupuncture), nor for comparison of one NSAID versus another NSAID, as these were mostly single‐trial comparisons and included many NSAIDs that are no longer in clinical use.

We originally intended to include in the SoF tables the proportions of participants who reported pain relief of 50% or greater. However, as this information was not included for most trials, we included a continuous measure of pain instead because this is how most trials measured pain.

Two people (CD and MW) used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to independently assess the certainty of a body of evidence related to studies that contributed data to the meta‐analyses for prespecified outcomes, and we reported the certainty of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. We used methods and recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2020). We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of studies by using footnotes, and we made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review when necessary. We provided the NNTB or the NNTH and absolute percentage change in the Comments column of the SoF table for dichotomous outcomes, as described in the Measures of treatment effect section above.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

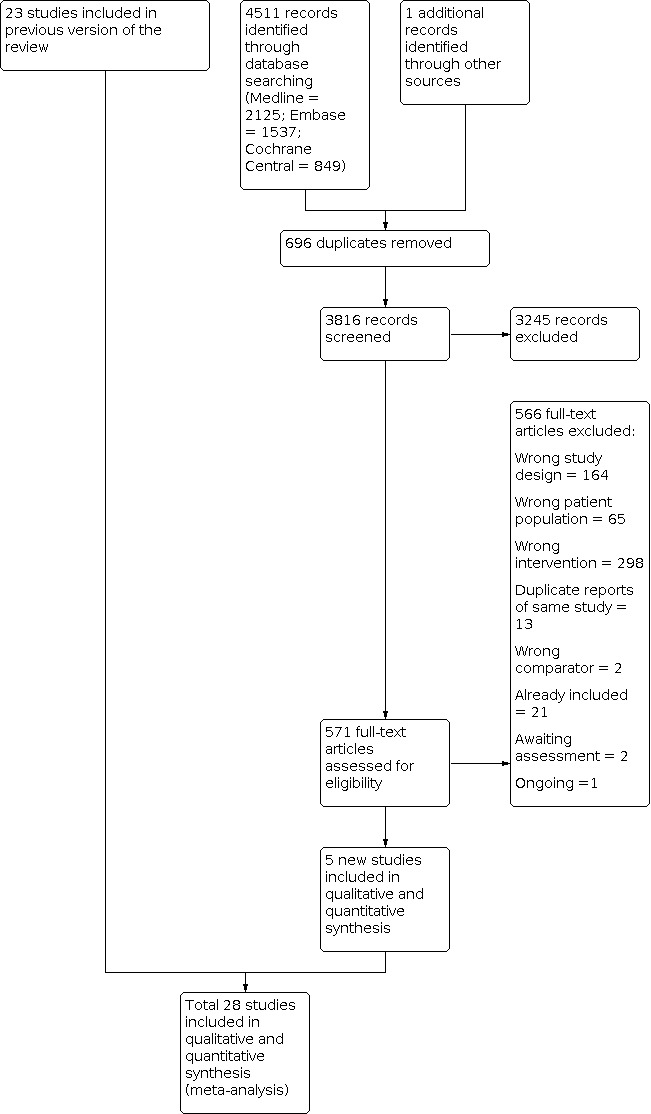

Cochrane Musculoskeletal updated the search for all gout review updates on 28 August 2020, searching for studies from July 2011 to August 2020. Searches for this update yielded a total of 4511 new records from the following databases: MEDLINE (2125), Embase (1537), and Cochrane CENTRAL (849). We also identified 1 eligible study from the references of other studies. After removing duplicates, we excluded 3245 records based on title and abstract screening. We then assessed 571 full‐text articles for eligibility. Of these, we included 5 new studies in this review update (Li 2013; Rainer 2016; Roddy 2020; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014). We excluded 566 full‐text articles for the following reasons: 164 because of wrong study design, 65 because of wrong patient population, and 298 because of wrong intervention. Thirteen reports were duplicates from the same studies, and 2 studies used the wrong comparator. A total of 21 studies were already included in the previous version of this review, 2 studies are awaiting classification, and 1 study is ongoing.

A flow diagram summarising the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The 28 included trials involved 3406 participants (mean 122 participants; range 20 to 416, with study duration ranging from 90 hours to 14 days). A full description of the included studies is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. Twenty‐six trials were reported in English, 1 in Portuguese (Klumb 1996), and 1 in German (Siegmeth 1976).

Diagnosis of gout and participant features

All included trials were RCTs. The diagnosis of gout was made on clinical grounds in 8 trials (Butler 1985; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Maccagno 1991; Roddy 2020; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977). Ten trials used the 1977 classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR 1977) (Cheng 2004; Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014), and 1 trial included only participants with gout confirmed by identification of MSU crystals in synovial fluid (Janssens 2008a). Eight trials used either clinical inclusion criteria (a clear history ‐ or the observation ‐ of at least two attacks of acute arthritis with abrupt onset and remission, history/observation of podagra, presence of tophi, history/observation of response to colchicine within 48 hours of therapy) or positive identification of MSU crystals in the synovial fluid for inclusion (Altman 1988; Axelrod 1988; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Siegmeth 1976). Zhou 2012 used the Criteria of Diagnosis and Therapeutic Effect of Diseases and Syndromes in Traditional Medicine (Traditional Chinese Medicine 1994).

All included studies recruited adults, and all but 1 study reported mean age of the study population (Lomen 1986); mean age of the whole study population ranged from 44 to 66 years. Twenty‐one trials included both males and females (Altman 1988; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Lederman 1990; Li 2013; Maccagno 1991; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Roddy 2020; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014). In these trials, the proportion of males varied between 69% and 97%. Five trials included only males (Axelrod 1988; Eberl 1983; Klumb 1996; Siegmeth 1976; Zhou 2012), and 2 trials did not describe gender distribution (Butler 1985; Lomen 1986).

Seven trials reported the mean duration of disease, which ranged from 5 to 17 years (Douglas 1970; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986; Siegmeth 1976; Terkeltaub 2013; Xu 2016; Zhou 2012). Four trials included only participants with monoarthritis (Janssens 2008a; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991). Two trials included participants with monoarthritis and oligoarthritis (maximum three joints involved) (Schumacher 2012; Terkeltaub 2013). Nine trials included participants regardless of the number of joints involved: 66% to 96% of participants had monoarthritis, and 5% to 34% had more than one joint involved (Axelrod 1988; Eberl 1983; Klumb 1996; Man 2007; Roddy 2020; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Willburger 2007; Zhang 2014). Nine trials described affected sites: the first metatarsophalangeal joint was affected in 27% to 100%, the knee in 18% to 47%, the ankle in 19% to 27%, the thumb in 5%, the wrist in 5% to 14%, and the elbow in 3% to 10% of participants (Axelrod 1988; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Klumb 1996; Li 2013; Roddy 2020; Schumacher 2002; Xu 2016).

Comparisons

Only 1 trial compared an NSAID (tenoxicam 40 mg) to placebo (Garcia de la Torre 1987).

Thirteen trials compared one NSAID to another NSAID (Altman 1988; Butler 1985; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Klumb 1996; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Shrestha 1995; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977). Although many of the studied NSAIDs are still registered, many are no longer commonly used in practice: NSAIDs studied included diclofenac (Cheng 2004), etodolac (Lederman 1990; Maccagno 1991), flufenamic acid (Douglas 1970), flurbiprofen (Butler 1985; Lomen 1986), ketorolac (Shrestha 1995), ketoprofen (Altman 1988; Siegmeth 1976), meclofenamate (Eberl 1983), meloxicam (Cheng 2004), nimesulide (Klumb 1996), and phenylbutazone (Butler 1985; Douglas 1970; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977). The duration of treatment ranged from 5 days in Altman 1988, Lomen 1986, and Shrestha 1995 to 10 days in Butler 1985; follow‐up ranged from 24 hours in Maccagno 1991 to 14 days in Altman 1988 and Eberl 1983.

Six trials compared a non‐selective NSAID (indomethacin, 50 mg 3 times daily) to a selective COX‐2 inhibitor (etoricoxib 120 mg once daily; celecoxib 50, 200, or 400 mg twice daily, or lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily) (Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). Treatment was given for 4 days in Xu 2016, 7 days in Willburger 2007, and 8 days in Rubin 2004Schumacher 2002 and Schumacher 2012; follow‐up ranged from 4 days in Xu 2016 to 14 days in Schumacher 2012.

Four trials compared NSAIDs (naproxen 500 mg twice daily or indomethacin 50 mg 3 times daily) to oral glucocorticoids (prednisolone 30 or 35 mg once daily) (Janssens 2008a; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Xu 2016). Drugs were given for 4 days in Xu 2016, Janssens 2008a, and Rainer 2016 and for 6 days in Man 2007; follow‐up ranged from 90 hours in Janssens 2008a and Xu 2016 to 14 days in Man 2007 and Rainer 2016.

One trial compared NSAIDs (diclofenac 75 mg twice daily for 7 days) to intramuscular glucocorticoids (betamethasone 7 mg once intramuscularly) (Zhang 2014). Participants were followed up for 7 days.

One trial compared an NSAID (indomethacin 50 mg 4 times daily) to adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) (40 international units (IU) intramuscularly in a single dose) (Axelrod 1988). Participants were followed for 1 year, and every attack during that year was treated with either indomethacin or ACTH.

One trial compared an NSAID (indomethacin 50 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 25 mg 3 times daily for up to 9 days) to rilonacept (320 mg subcutaneously) and to NSAID plus rilonacept (Terkeltaub 2013).

One trial compared an NSAID (indomethacin 25 mg 3 times daily for 5 days) to acupuncture combined with infrared irradiation (Zhou 2012).

One trial compared an NSAID (naproxen 250 mg 3 times daily) to colchicine (500 mcg 3 times daily) (Roddy 2020).

Outcomes

Four trials included our primary benefit endpoint of proportion of participants improved by 50% or more (Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986), and 20 trials included our primary harms endpoint of withdrawal due to adverse events (Altman 1988; Axelrod 1988; Butler 1985; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Lederman 1990; Li 2013; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Man 2007; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). Other endpoints were variably reported.

NSAID versus placebo (1 trial)

The primary outcomes of this trial were time to improvement and time to resolution; pain and the presence of inflammation were assessed as secondary outcomes. In addition, both of our primary outcomes were reported (Garcia de la Torre 1987).

One NSAID versus another NSAID (13 trials)

Only 3 trials reported proportions of participants improved by 50% or more (Eberl 1983; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986). All trials used ordinal scales to report pain, with the exception of Klumb 1996, which used a VAS.

Seven trials assessed 'inflammation' as an outcome, but the method of assessment varied across trials (Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Smyth 1973). Cheng 2004 used an inflammatory score that assessed tenderness, swelling, and restriction of function of the inflamed joint. Douglas 1970 reported the number of days needed for the redness, swelling, tenderness, or heat to resolve. Eberl 1983 reported numbers of participants who had no redness, swelling, or function restriction at the end of treatment. Lederman 1990 and Lomen 1986 assessed pain, swelling, erythema, and tenderness on a 5‐point scale.

Five trials assessed function (Altman 1988; Cheng 2004; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Maccagno 1991). Altman 1988 and Cheng 2004 assessed function as part of a total 'inflammatory' score. The other 3 trials reported whether there was a limitation in motion of the index joint (absent/none or present).

Five trials included a measure of participants' global assessment (Altman 1988; Cheng 2004; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991), and no trials included a measure of HRQoL.

Twelve trials included the numbers of participants with AEs and provided a description of the AEs (Altman 1988; Butler 1985; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Klumb 1996; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Shrestha 1995; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977).

Non‐selective NSAIDs versus selective cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibitors (6 trials)

None of these trials measured our primary benefit endpoint, but they all reported withdrawals due to AEs. All 6 trials measured pain as a primary outcome, using a Likert scale (Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016), or a 5‐point ordinal scale (Schumacher 2002). FIve trials measured inflammation and participants' global assessment as secondary outcomes (Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). One trial assessed function (Xu 2016). Willburger 2007 was the only trial that measured HRQoL as a secondary outcome, using SF‐36 and EuroQoL Group Quality of Life Questionnaire based on 5 dimensions (EQ‐5D) questionnaires. Six trials included numbers of participants with AEs and provided a description of the AEs (Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016).

NSAIDs versus oral glucocorticoids (4 trials) or intramuscular (IM) glucocorticoids (1 trial) or adrenocorticotropin hormone (1 trial)

Neither of the 4 trials comparing NSAID versus oral glucocorticoid included our primary benefit endpoint; all trials included numbers of withdrawals due to AEs (Janssens 2008a; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Xu 2016). All 4 trials measured pain as mean pain reduction. Three trials measured function (Janssens 2008a; Rainer 2016; Xu 2016). Two trials included measures of inflammation (redness, tenderness, and swelling) (Rainer 2016; Xu 2016). Rainer 2016 and Xu 2016 assessed participants' global assessment. Only Rainer 2016 assessed HRQoL (SF‐36) but did not report the results of this outcome (these also were not obtained from study authors). All trials included the numbers of participants with AEs and provided a description of the AEs. Three trials reported withdrawals due to AEs (Janssens 2008a; Man 2007; Xu 2016).

The trial that compared NSAIDs to intramuscular glucocorticoids reported our main benefit outcome (number of patients without pain) after assessing pain on a Likert scale (Zhang 2014). Other outcomes that were assessed were measures of inflammation (swelling, tenderness) and patients' and physicians' assessments of global response to therapy.

The trial that compared NSAIDs to ACTH did not include any of our main benefit outcomes but did assess pain as the number of hours needed to achieve complete pain relief (Axelrod 1988). This trial also reported withdrawals due to AEs and numbers and types of adverse events.

NSAIDs versus rilonacept (interleukin‐1 inhibitors) (1 trial)

One trial compared NSAID to rilonacept (Terkeltaub 2013). This trial measured change in pain from baseline using both Likert and numerical scales and withdrawals due to adverse events but none of the other relevant measures in this review.

NSAIDs versus acupuncture (1 trial)

One trial compared NSAID to acupuncture. This trial measured only mean change in pain (Zhou 2012).

NSAIDs versus colchicine (1 trial)

Roddy 2020 compared NSAID to colchicine. This trial measured change in pain intensity from baseline as a primary outcome on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale (NRS). No measure of inflammation was included. Quality of life was assessed using the EuroQoL Group Quality of Life Questionnaire based on 5 dimensions and a 5‐level scale (EQ‐5D‐5L). Adverse events and descriptions of adverse events were provided.

Excluded studies

We excluded 20 trials after detailed review. Reasons for exclusion are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Nine studies were not RCTs (Arnold 1988; Bach 1979; Cunovic 1973; Cuq 1973; Ecker‐Schlipf 2009; Janssens 2009; Navarra 2007; Steurer 2016; Werlen 1996).

We excluded 1 study because participants with renal insufficiency, history of gastrointestinal AEs to NSAIDs, peptic ulcer or gastritis, or any other contraindication to indomethacin were placed in the triamcinolone group (non‐randomised), and other participants were randomised (Alloway 1993). Data for randomised participants were not reported separately.

One trial did not include participants with acute gout (Kudaeva 2007). We excluded 3 trials because the NSAIDs used (feprazone, proquazone, and fenoprofen) are no longer available (Reardon 1980; Ruotsi 1978; Weiner 1979). We excluded 1 trial because the inclusion population consisted of patients with peptic haemorrhage ulcers who were having an acute gout flare (Xu 2015).

We excluded 2 trials because they compared two different doses of the same drug (Tumrasvin 1985; Valdes 1987).

We identified an additional trial comparing apremilast to indomethacin from the trial registry search, but the trial had been withdrawn (NCT00997581).

Studies awaiting classification

For one trial, only the conference abstract was available at the time of publication of this review (Katona 1988). Another study is written in Chinese and is awaiting translation (Yin 2005). We categorised trials as awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table).

Ongoing studies

One ongoing trial ‐ ChiCTR1800019612 ‐ is recruiting participants to study effects of NSAID plus ozone treatment of autologous blood versus ozone treatment of autologous blood.

Risk of bias in included studies

We judged most trials (26/28; 93%) as having unclear ‐ Altman 1988; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007 ‐ or high risk of bias ‐ Axelrod 1988; Butler 1985; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Roddy 2020; Sturge 1977; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012. We judged only 2 trials (8%) as having low risk of bias (Li 2013; Shrestha 1995).

A description of the risk of bias of included studies is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. Summaries of the risk of bias of individual trials are shown in Figure 2 and of included trials as a group in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Sequence generation (selection bias)

Fourteen trials reported an appropriate sequence generation (Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Janssens 2008a; Li 2013; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Roddy 2020; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Smyth 1973; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016; Zhou 2012). For 12 trials, the method of sequence generation was unclear (Altman 1988; Butler 1985; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Rubin 2004; Siegmeth 1976; Sturge 1977; Terkeltaub 2013; Zhang 2014). We judged 2 trials as having high risk of bias for the item sequence generation: 1 trial because participants were alternately assigned to one of the two treatment groups (Axelrod 1988), and the other trial because although stated as randomised with no description of the randomisation method, baseline characteristics were significantly different between the two treatment groups (Lederman 1990).

Allocation

For 17 trials, concealment of drug allocation was inappropriately described or was not described at all, and we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Altman 1988; Butler 1985; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Klumb 1996; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Siegmeth 1976; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007; Zhang 2014). We assigned 3 trials to be at high risk of allocation bias because the treatment was not concealed (Axelrod 1988; Sturge 1977; Zhou 2012). Eight trials were at low risk of selection bias, as the method of allocation concealment was clearly described (Li 2013; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Roddy 2020; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Smyth 1973; Xu 2016).

Blinding

We judged 8 trials as having unclear risk of performance bias regarding blinding of study personnel (Altman 1988; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977). For 6 trials (Axelrod 1988; Cheng 2004; Roddy 2020; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012), we considered risk of performance bias to be high because participants were not blinded. We judged 14 trials to be at low risk of performance bias, as the method of blinding participants and study personnel was adequately described (Butler 1985; Douglas 1970; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Klumb 1996; Li 2013; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007)

We judged 8 trials as having unclear risk of detection bias for self‐reported outcomes because blinding of participants was not described or was unclear (Altman 1988; Eberl 1983; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977). We assigned 6 trials high risk of bias because the trials were not blinded (Axelrod 1988; Cheng 2004; Roddy 2020; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012). We judged 14 trials to be at low risk of detection bias for self‐reported outcomes, as the method used to blind participants was adequately described (Butler 1985; Douglas 1970; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Janssens 2008a; Klumb 1996; Li 2013; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007).

We judged 13 trials to be at unclear risk of detection bias for assessor‐reported outcomes because blinding of outcome assessors was not described or was unclear (Altman 1988; Butler 1985; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Lederman 1990; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977; Terkeltaub 2013). We assigned 5 trials high risk of detection bias for assessor‐reported outcomes because the trials were not blinded (Axelrod 1988; Roddy 2020; Xu 2016; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012). We judged 10 trials to be at low risk of detection bias for assessor‐reported outcomes, as the method of blinding outcome assessors was adequately described (Cheng 2004; Janssens 2008a; Li 2013; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Willburger 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 12 trials as having unclear risk of bias for incomplete outcome data because they did not report if there were withdrawals or missing data, or how withdrawals or missing data (or both) were handled (Altman 1988; Axelrod 1988; Butler 1985; Eberl 1983; Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Roddy 2020; Schumacher 2002; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). We judged the remaining 16 trials to be at low risk of attrition bias (Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Janssens 2008a; Lederman 1990; Li 2013; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Siegmeth 1976; Terkeltaub 2013; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012).

Selective reporting

Twenty trials were at low risk of reporting bias (Altman 1988; Axelrod 1988; Cheng 2004; Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983; Janssens 2008a; Lederman 1990; Li 2013; Lomen 1986; Maccagno 1991; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Shrestha 1995; Siegmeth 1976; Smyth 1973; Sturge 1977; Terkeltaub 2013; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). We assigned 6 trials unclear risk of selective reporting bias (Garcia de la Torre 1987; Klumb 1996; Man 2007; Rainer 2016; Zhang 2014; Zhou 2012). Man 2007 reported secondary outcomes, but not in the prespecified manner. Klumb 1996 did not provide a clear description of outcomes and provided inappropriate between‐group comparisons (only status scores). Garcia de la Torre 1987 and Rainer 2016 did not report all prespecified outcomes. Zhang 2014 reported an outcome that was not prespecified and did not report anywhere whether there was a statistically significant difference in this reported outcome. Other prespecified outcomes were reported, but again, it was not reported whether differences were statistically significant. Zhou 2012 did not report inflammation but named it in the methods section, so it is unclear if this was going to be a separate outcome.

We judged 1 trial as having high risk of bias for this criterion because it did not report one prespecified outcome ‐ pain measured on an ordinal scale (Butler 1985).

Other potential sources of bias

Two trials were judged to be at high risk of other bias (Douglas 1970; Eberl 1983). Eberl 1983 used a higher initial meclofenamate dose compared with the indomethacin dose used in the control group, which may have biased the results in favour of the meclofenamate group. In Douglas 1970, the mean age of participants was significantly higher in the flufenamic acid group (57.2 years) than in the phenylbutazone group (47.6 years).

In Sturge 1977, there was also a difference in age between the two groups: participants in the naproxen group were older (mean age 58.8 years, range 34 to 84) than those in the phenylbutazone group (mean age 50.4 years, range 30 to 73).

Four studies were subject to funding by manufacturers, but these relationships did not appear to affect reporting of study results, and it is unclear if there was any bias in the study design as a result of the funding relationships.

The rilonacept study was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceutics Inc. (manufacturers of rilonacept); employees of Regeneron Pharmaceutics Inc. participated in study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript (Terkeltaub 2013). It is unclear if this relationship resulted in any biased conduct in the trial.

For Schumacher 2002, Merck Research Laboratory provided funding to all participating investigators to cover the costs of patient procedures and investigations; one study author was on the Merck advisory board, one was a consultant for Merck, and four were employed by Merck and owned shares of Merck common stock.

Editorial support was funded by Pfizer for Schumacher 2012.

Four authors of Willburger 2007 were employed by Novartis Pharma; one author was a speaker for Novartis. It is unclear if this relationship resulted in any biased reporting of results in the trial.

Roddy 2020 reported a difference in length of treatment; naproxen was given for 4 days and colchicine for 7 days.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

NSAIDs versus placebo

Benefits

One trial of 30 participants compared an NSAID (tenoxicam 40 mg) with placebo (Garcia de la Torre 1987). All results are summarised in Table 1. NSAIDs may result in decreased pain (higher proportion of participants achieving ≥ 50% improvement in pain). Low‐certainty evidence downgraded for bias and imprecision suggests there may be a clinically significant improvement in the number of patients who achieve more than 50% reduction in overall pain (reported as 'spontaneous pain') at 24 hours (11/15 in the tenoxicam group, 4/15 in the placebo group; risk ratio (RR) 2.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1, 6.7), with absolute change of 47% more (3.5% more to 152.5% more) with NSAIDs and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 3 (95% CI 2 to 12; Analysis 1.1). There was no difference in the number of participants who achieved more than 50% reduction in pain with movement at 24 hours (4/15 in the NSAIDs group versus 1/15 in the placebo group; RR 4.0, 95% CI 0.5 to 31.7) and at day 4 (13/15 in the NSAIDs group versus 14/15 in the placebo group; RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.2; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: NSAIDs versus placebo, Outcome 1: Pain: ≥ 50% improvement in pain

Low‐certainty evidence downgraded for bias and imprecision suggests no reported between‐group differences in the proportions of participants with more than 50% improvement in joint swelling at 24 hours (5/15 in the NSAIDs group versus 2/15 in the placebo group; RR 2.5, 95% CI 0.6 to 10.9) or at day 4 (13/15 in the NSAIDs group versus 12/15 in the placebo group; RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.5), with absolute change of 6.4% more patients (16.8% fewer to 39.2% more).

NSAIDs may have no effect on function (≥ 50% improvement in pain with movement at 24 hours assessed on a 4‐point scale (1 = complete resolution to 4 = increased pain); RR 4.0 (95% CI 0.5 to 31.7)), with absolute change of 20% more (3.3% fewer to 204.9% more).

The trial did not measure global assessment of treatment success nor health‐related quality of life (HRQoL).

Harms

There were no withdrawals due to adverse events in either group in this trial and no significant between‐group differences in numbers of adverse events (0/15 in the NSAIDs group versus 2/15 in the placebo group; RR 0.2, 95% CI 0.0 to 3.8), with absolute change of 10.6% fewer (13.2% fewer to 38% more; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: NSAIDs versus placebo, Outcome 3: Withdrawals due to adverse events

Non‐selective NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibitors

Six trials including 1266 participants compared NSAIDs (indomethacin 50 mg 3 times daily or 75 mg twice daily) to COXIBs (etoricoxib 120 mg once daily; celecoxib 50, 200, or 400 twice daily; or lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily), and data could be pooled (Li 2013; Rubin 2004; Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007; Xu 2016). Two trials were at unclear risk of selection bias (Rubin 2004; Willburger 2007), 1 was at high risk of performance and detection bias (Xu 2016), and it is unclear whether funding in 3 trials provided by the manufacturer resulted in any bias (Schumacher 2002; Schumacher 2012; Willburger 2007). One trial was at low risk of bias (Li 2013). All results are summarised in Table 2.

Benefits

Six trials (1044 participants) showed no between‐group differences with respect to mean pain change from baseline on a 0 to 4 Likert scale (where 0 is no pain) at day 1 or 2 (mean difference (MD) 0.0, 95% CI ‐0.1 to 0.1; Analysis 2.1). There was no statistically or clinically significant difference between NSAIDs and COXIBs with regards to inflammation measured on a 0 to 3 Likert scale (0 is no swelling; MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐0.1 to 0.2; 6 trials with 1044 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence downgraded for bias; Analysis 2.2). Xu 2016 assessed function as pain with activity. There was no mean difference from baseline between the two groups (MD ‐0.0, 95% CI ‐0.2 to 0.2; low‐certainty evidence downgraded for bias and imprecision; Analysis 2.3). Moderate‐certainty evidence (downgraded for bias) from 4 trials (730 participants) showed no between‐group differences with respect to patients' global assessment of treatment success (MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐0.0 to 0.2; Analysis 2.4). One trial with 222 participants reported no between‐group differences with respect to HRQoL measured by the 36‐Item Short Form questionnaire (SF‐36) Mental Health component (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐6.7 to 6.3; low‐certainty evidence downgraded for bias and imprecision; Analysis 2.5; Willburger 2007).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs), Outcome 1: Pain: mean change difference from baseline on a 5‐point Likert scale

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs), Outcome 2: Inflammation: mean change difference in swelling from baseline

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs), Outcome 3: Function: mean change difference in pain with activity from baseline

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs), Outcome 4: Participants' global assessment of treatment success

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: NSAIDs versus cyclo‐oxygenase (COX)‐2 inhibitors (COXIBs), Outcome 5: Health‐related quality of life measured by 36‐item Short Form

Harms