Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are known to be modulated by membrane cholesterol levels, but whether or not the effects are caused by specific receptor-cholesterol interactions or cholesterol’s general effects on the membrane is not well-understood. We performed coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) simulations coupled with structural bioinformatics approaches on the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) and the cholecystokinin (CCK) receptor subfamily. The β2AR has been shown to be sensitive to membrane cholesterol and cholesterol molecules have been clearly resolved in numerous β2AR crystal structures. The two CCK receptors are highly homologous and preserve similar cholesterol recognition motifs but despite their homology, CCK1R shows functional sensitivity to membrane cholesterol while CCK2R does not. Our results offer new insights into how cholesterol modulates GPCR function by showing cholesterol interactions with β2AR that agree with previously published data; additionally, we observe differential and specific cholesterol binding in the CCK receptor subfamily while revealing a previously unreported Cholesterol Recognition Amino-acid Consensus (CRAC) sequence that is also conserved across 38% of class A GPCRs. A thermal denaturation assay (LCP-Tm) shows that mutation of a conserved CRAC sequence on TM7 of the β2AR affects cholesterol stabilization of the receptor in a lipid bilayer. The results of this study provide a better understanding of receptor-cholesterol interactions that can contribute to novel and improved therapeutics for a variety of diseases.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of integral membrane proteins in eukaryotic cells. Characterized by a conserved seven transmembrane helical bundle, GPCRs are classified into five distinct phylogenetic families: class A/rhodopsin, class B/secretin, class C/glutamate, class F/frizzled, and Adhesion, with the vast majority of receptors being found in class A [1] (Fig. 1A). GPCRs play essential roles in physiological pathways and cell signaling events, making them important potential drug targets [2].

Figure 1. Location and conservation of important residues across Class A GPCRs.

(A) Snake plot shows the location of well-conserved residues and motifs in class A GPCRs in the transmembrane bundle. (B) Cartoon visualization of the most conserved residues on each transmembrane helix as well as well-conserved motifs. Eleven well-studied GPCRs are shown.

GPCRs are commonly found residing in lipid rafts, which are highly ordered regions of the bilayer due to their high cholesterol content [3]. GPCR sequestration to these ordered microdomains had led to the hypothesis that cholesterol acts as an allosteric modulator for GPCR functions. Studies involving membrane cholesterol depletion showed specific altered signaling for the β2–Adrenergic Receptor (β2AR) [4] the cannabinoid receptor CB1 [5], and serotonin receptor 5HT1A [6, 7]; while cholesterol presence is required for the high affinity active state of the oxytocin receptor [8, 9]. Molecular spatial distribution analysis showed high density distribution of cholesterol around Pro7.48 (Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering) [10] at the bottom of TM7 of rhodopsin associated with receptor activation [11] (Fig. 1A).

Additional evidence suggested that other receptors (e.g. Smoothened, chemokine receptor CXCR2, and GPR183) may directly bind cholesterol through specific interactions [12–15] with multiple specific GPCR-cholesterol interaction sites having been identified [16–18]. The CCM motif, first characterized from a structure of the β2AR, is strictly conserved in 21% of class A GPCRs with 44% of class A receptors containing a slightly relaxed form of the motif [19]. CRAC sequences, defined as (−(L/V)-(X1–5)-Y-(X1–5)-(R/K)-), where X1–5 represents 1–5 residues of any amino acid, are considered the most well-known cholesterol recognition motif in literature and are found on many GPCRs [17]. Cholesterol molecules were clearly resolved in the crystal structures of numerous receptors [18], but questions remain regarding whether the cholesterol molecules found in these crystal structures represent physiologically relevant and specific interactions, or if they are simply crystallization artifacts due to the abundance of cholesterol in the lipid bilayer and proximity to receptor molecules.

Alternatively, there is evidence suggesting that the observed cholesterol effects arise indirectly through the physical effects of cholesterol on the lipid bilayer [20]. Cholesterol is known to alter membrane fluidity [21], thickness [22], and curvature [23]. Membrane fluidity was shown to have a direct effect on ligand binding at the 5HT1A [24] and the type-1 cholecystokinin receptor (CCK1R) [8]. Similarly, membrane thickness and curvature is known to affect the active/inactive equilibrium of Rhodopsin [25]. Taken together, there is a critical need to address and reconcile the apparent ambiguities in how cholesterol exerts its effect on GPCR functions.

Here, we set out to probe the specificity of cholesterol-GPCR interactions through a combination of coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) simulations [26, 27] with structural bioinformatics and experimental validation using β2AR as the model system and apply the structural dynamics and bioinformatics approaches to the CCK receptor family. CGMD has been widely used to predict and elucidate detailed interactions of GPCRs with lipids [27–29], in particular the interaction of cholesterol with GPCRs [30–33]. The MARTINI CG model that we are using here constrains the secondary structure and prevents conformational changes [34]; therefore, our results report on cholesterol-protein interactions with protein conformations close to the experimental crystal structures or models and do not include either conformational changes induced by cholesterol or different conformational states of the receptors. All-atom MD simulations do not share the same limitations but are computationally much more expensive and thus limited in the length of achievable simulations and sampling of protein-lipid interactions [33]. Given the previous successes of CGMD simulations [30–33] and the need to collect statistics to obtain reasonable estimates of long cholesterol binding times, we chose CGMD as the appropriate level of approximation that generates sufficient sampling. Further, we focus the study on the CCK receptor family due to the differential effects cholesterol exerts: the CCK1R ligand binding and downstream signaling are both modulated by membrane cholesterol levels, while the highly homologous (53% identity overall, and 69% in the transmembrane regions) gastrin receptor (CCK2R) is unaffected by cholesterol [35]. Even though both CCK receptor subtypes share cholesterol recognition motif sites, the functional implications of membrane cholesterol composition are quite distinct. Our results show that the CCK receptors interact with cholesterol through different motifs despite similar recognition sequences on the primary level. The CRAC motif at the bottom of TM3 has been identified as the functionally important site in CCK1R [36]. The CCK1R has been implicated as a potential therapeutic target to treat metabolic syndrome and obesity, with an allosteric modulator designed that can prevent the inhibitory effects of the high cholesterol environment associated with obese patients [37, 38].

Lastly, we discover a new CRAC motif near the end of transmembrane-helix seven (TM7) that is conserved across 38% of class A GPCRs (Fig. 1A). The results reported herein elucidate GPCR-cholesterol interactions in greater detail and could prove insightful in the development of additional allosteric therapeutics specifically targeting the CCK1R.

Results:

We performed CGMD simulations of β2AR and the two CCK receptors in a mixed POPC:cholesterol membrane and analyzed the residency times of cholesterols at a per-residue resolution. Simulations were performed in 20% and 40% cholesterol. The 20% simulations appeared to better discriminate residues with long residency times from ones with shorter times and we therefore present the results for 20% cholesterol while results for 40% cholesterol are shown in the Supplementary Information. In the following discussion we focus on computational results that are consistent between the 20% and 40% simulations as the most robust findings. For the β2AR , residues from the CCM motif including I1534.45 and W1584.50 showed peaks just below the labeling cutoff of our analysis (τslow= 140 and 86 ns, respectively). I551.54 also showed prolonged interaction times with cholesterol molecules (τslow=84 ns just below the labeling cutoff in Fig. 2A). In certain structure models (e.g., PDB: 2RH1) a cholesterol molecule is found within 5 Å from this residue. Some of the strongest signals arose from V1574.49, T1644.56, and W3137.40 (Fig. 2A). Though not observed in crystal structures, these residues have been implicated to interact with cholesterol as well [30, 39, 40].

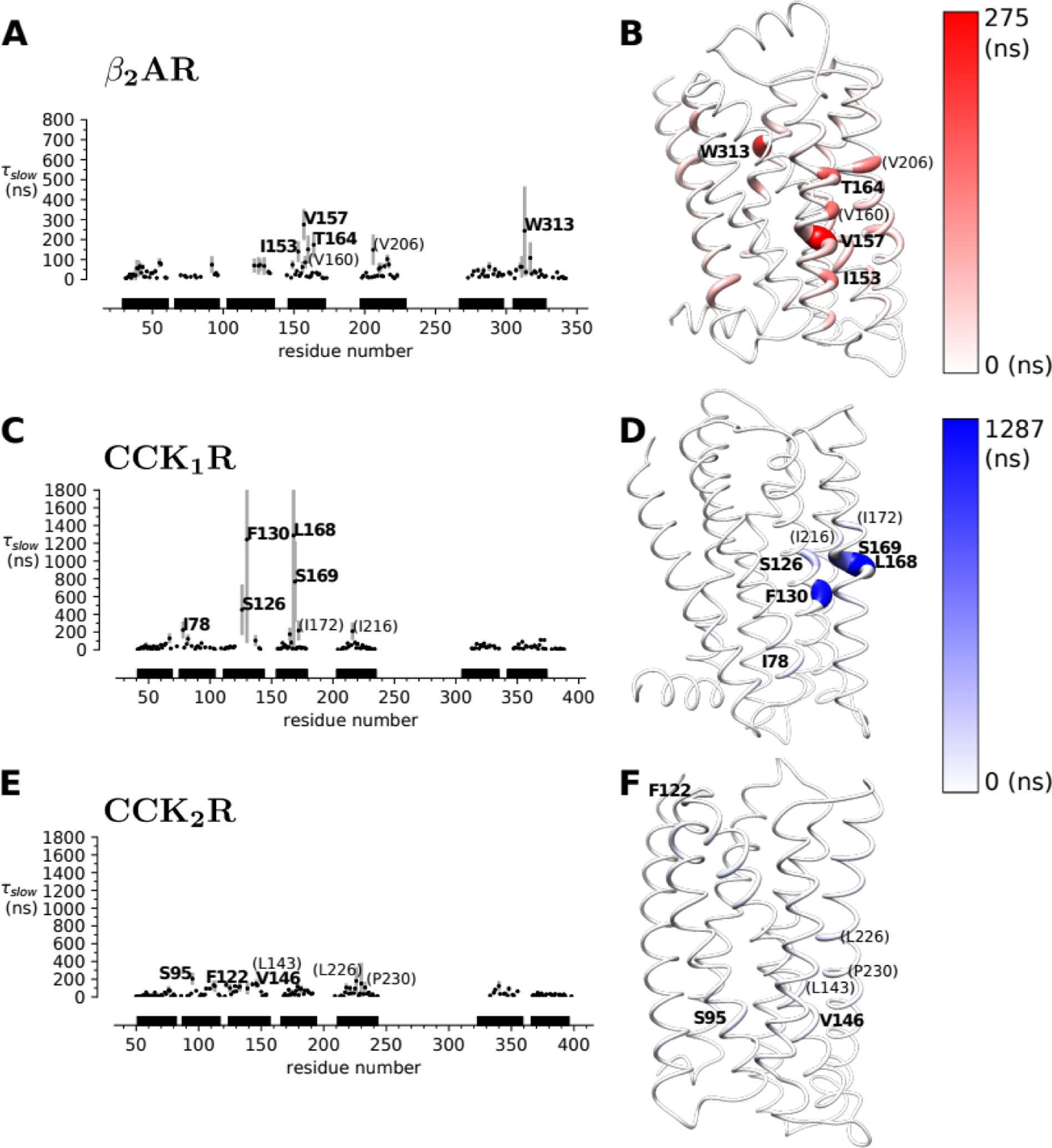

Figure 2. Cholesterol residency times τslow by residue from CGMD simulations with 20% cholesterol.

(A), (C), (E): Residency times at the β2AR, CCK1R, and CCK2R. Data points are the means over multiple simulation repeats and approximately 20-μs simulation blocks, with the standard deviation shown as a symmetric bar. Residues for which the mean τslow is at least three times the overall mean over all residency times in the protein are explicitly labelled. Residues that show consistently high residency times in the 20% and 40% cholesterol simulations are bold-faced whereas other residues that are only apparent in either simulation set are shown in parentheses in normal typeface. In C, the error bars of F130 and L168 are truncated at high values to focus the range of the plot on the means (which is set to to be comparable between the 20% data here and the 40% data in Supplementary Fig. S2). (B), (D), (F): Structure models highlight residues with long residency times. The radius of the ribbon is scaled proportional to the average residency time and colored according to the color scale.

With the successful application of our CGMD approach to β2AR, we next used the same methods to study the CCKRs. On the CCK1R, we observed strong receptor-cholesterol interactions surrounding TM3 with the highest residency time out of all of the receptor targets in this study. Furthermore, few CCK1R residues have residency times higher than the background signal. A binding pocket at TM3 is further supported by long interactions at F1303.41, L1684.52, and S1694.53 (Fig. 2). While the CCK1R-cholesterol interactions were mainly centered around TM3, the CCK2R interactions were more spread throughout the receptor and residency times were all close to background. However, some interactions (such as at S952.45) suggest that CCK2R may also interact with cholesterol molecules via the CCM motif mentioned above (Fig. 2, 3C). Direct comparison of the residency times for structurally equivalent residues between the two receptors demonstrated that residues in the CCK1R typically bound cholesterol longer than the corresponding residues in CCK2R (Fig. 3B). These results were consistent between the simulations with 20% and 40% cholesterol concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S3), implying that the CGMD simulations are able to differentiate which of the two homologous receptors interacts preferentially with cholesterol.

Figure 3. Differential interactions with cholesterol in the CCK subfamily.

(A) Structure models of the CCK receptors. CRAC sequences are shown in blue and the CCM motif is shown in red. Spheres represent residues that showed differential cholesterol residency during the simulation and are colored by Δτ. (B) Difference in residency times Δτ = τslow(CCK1R) − τslow(CCK2R) for equivalent residues according to the sequence alignment. Maroon represents residues residues that bind cholesterol for longer times (higher τslow) in CCK1R whereas cyan represents residues with higher τslow in CCK2R than in CCK1R. Error bars on the differences represent the standard deviation. (C) Sequence alignment of the two CCK receptors. The CCM motif is highlighted in red and CRAC sequences are highlighted in blue. Arrows highlight the residues that make the recognition sequence. The specific fixed residues of these motifs are annotated with their canonical residue numbers.

During our analysis of the interactions observed on the β2AR, we noticed a CRAC sequence made up of residues L3247.51, Y3267.53, and R3287.55 on the intracellular side of TM7. This CRAC site is centered around the highly conserved NPxxY motif in class A GPCRs [41]. Thus, we aligned all class A GPCRs (excluding olfactory receptors) using the structure-based alignment tool from the GPCR database [42] to see if this new CRAC site is also present in other class A GPCRs [42]. In all, 38% of the 285 class A GPCRs that were aligned and analyzed were found to contain a CRAC sequence surrounding the NPxxY motif (Supplementary File S1). On the CCK receptors, this novel CRAC sequence consists of V3657.48, Y3707.53, and K3747.57 on the CCK1R, and V3857.48, Y3907.53, and R3947.57 on the CCK2R (Fig. 3C).

To better understand possible cholesterol interactions on TM7, we performed a series of mutations on the β2AR and used the LCP-Tm assay to quantify the stabilizing effects of cholesterol binding to the receptor [43]. We analyzed single point mutations at the newly discovered CRAC sequence along with other residues on TM7. A summary of all mutations tested is shown in Table 1. Two mutations, Y326A7.53 and F336A8.54, nearly abolished protein expression completely. Of the β2AR constructs with reasonable expression, four of the seven remaining mutants were highly aggregated after purification in the presence of the high-affinity ligand timolol (Table 1). Due to poor protein expression and aggregation of most of the mutants, we were only able to collect LCP-Tm data on two mutant receptors alongside an unmutated receptor control sample. The first, F321A7.48 (located two helix turns near W3137.40) was included as it could potentially interact with cholesterol molecules on the TM7 CRAC site. This residue has also been implicated to interact with cholesterol in previous studies [30]. Similarly, R328A7.55 was incorporated due to its position in the TM7 CRAC sequence (Fig. 4C). Previous studies showed the unmutated β2AR to be stabilized by 2.3°C when 10% (w/w) cholesterol was added to the host lipid monoolein relative to the monoolein-only sample [43]. In our experiments, the Tm of unmutated β2AR is 43.45 ± 0.65 °C (monoolein-only) and 45.15 ± 0.54 °C (monoolein with 10% cholesterol) resulting in a ΔTm of 1.71 ± 0.85°C (Fig. 4A/B). The F321A and R328A mutations showed similar transition temperatures to the unmutated control in cholesterol-free assays, with Tm values of 42.65 ± 0.21 and 43.10 ± 0.74 °C, respectively. In cholesterol, the F321A mutant had a very slight increase in stability with a ΔTm value of 0.46 ± 0.77 °C. Surprisingly, the R328A mutant had the largest ΔTm value at 5.75 ± 1.65 °C with the addition of cholesterol into the host lipid (Fig. 4). Given that CGMD simulations showed a clear pattern of differential cholesterol binding in the CCKRs, we performed CGMD simulations of the R328A mutant to test if the mutation would have a strong effect on cholesterol binding as measured by our residence time analysis. The difference in residence times between WT and mutant receptor were not significantly different from 0 (Supplementary Fig. 4), unlike the case for CCK1R vs CCK2R.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the mutations on the β2AR and their results.

| Construct | Purpose | Behavior | ΔTm(°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmutated | Control | Good | 1.71±0.85 |

| W313A | Flagged in simulation | High Aggregation | - |

| S319A | Control mutation | Slight aggregation. Biphasic data could not be fit to Boltzmann curve in LCP-Tm |

- |

| I319A | Control mutation | Heavily Aggregated | - |

| F321A | Theoretical interaction with cholesterol on TM7 | Good | 0.46±0.77 |

| L324A | Part of CRAC sequence on TM7 | Heavily Aggregated | - |

| I325A | Control Mutation | Heavily Aggregated | - |

| Y326A | CRAC sequence | Expression Abolished | - |

| R328A | CRAC sequence | Good | 5.75±1.65 |

| F336A | Theoretical interaction with cholesterol | Expression Abolished | - |

Figure 4. A conserved CRAC sequence modulates cholesterol-induced stability on the β2AR.

(A) Mean transition temperatures from LCP-Tm assay with and without cholesterol in the LCP. (B) ΔTm values for each mutant. (C) Alignment of CB1R, β2AR, and the CCK receptors. The conserved NPxxY motif on helix 7 is shown in blue. Residues fulfilling the CRAC sequence are shown in red.

Discussion:

The β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) was initially used as the model system to initially test and validate the methods outlined in this study. The structure, function, and cholesterol sensitivity of the β2AR have been extensively characterized with multiple cholesterol recognition motifs (CCM, CRAC) already identified on this receptor [31]. Overall, we found that our CGMD simulations on the β2AR revealed receptor-cholesterol interactions consistent with previously published literature results [19, 31, 39, 40].

Our simulations on the CCK receptor family showed differential cholesterol binding despite a high sequence homology between these receptors. Experiments on chimeras of the two receptors showed that the CRAC motif at the bottom of TM3 is responsible for the differential cholesterol sensitivity between the two receptors [35], consistent with our simulation data. Furthermore, the CCK1R Y140A mutation at the bottom of TM3 within this CRAC motif has been shown to mimic the wildtype CCK1R conformation in a high cholesterol environment along with the loss of cholesterol sensitivity [35, 44]. Our simulations predict that the CCK1R mainly interacts with cholesterol molecules via F1303.41. Taken together, our results along with the previously published data suggest that cholesterol binds the CCK1R on TM3. Strong cholesterol interactions around position 3.41 are intriguing as mutation of this position to tryptophan is commonly performed during receptor engineering for structural studies, and has been included in the thermo-stabilization of numerous receptors for crystallization [45–47]. Initially discovered on β2AR, mutation of the residue at this position (3.41) decreased affinity for small molecule ligands 2-fold while increasing recombinant expression by nearly 4-fold and purified monomer yield by 5-fold [46]. Position 3.41 mutations to tryptophan have also been successfully extended to chemokine, serotonin, and dopamine receptor structural studies [45]. Taken together, the ability to affect receptor expression, yield, and stability as well as broadly being applicable to other GPCRs underscore the potential importance of this residue in GPCR physiology. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to presume that cholesterol interactions at 3.41 could be responsible for the cholesterol sensitivity of the CCK1R (without necessarily affecting the expression levels, given that tryptophan may lead to a stronger interaction with lipid or detergent headgroups that may compensate for missing stabilizing protein-cholesterol interactions) [48, 49].

The CCK2R seems to mainly interact with cholesterol via the CCM as one of the strongest signals was from S952.45 at the bottom of TM2 but it appears to interact with cholesterol with lower specificity and affinity than CCK1R. In the CGMD simulations, CCK1R interacted with cholesterol for much longer and at more specific residues than its insensitive homolog CCK2R (Fig. 3B). These results imply that specific cholesterol-receptor binding and interaction could be responsible for the difference in physiological effects between the two CCK receptors seen in a high cholesterol environment. Although indirect effects of cholesterol on membrane curvature could be responsible for modulating receptor functions, our data suggest that CCKRs bind cholesterol specifically and differentially. Thus, the CCKRs may be insensitive to the global effects of cholesterol on lipid bilayer curvature, fluidity, and microdomain-receptor sequestration. Our simulations agree with previous literature results that TM3, and specifically F130, is responsible for the differential effect of membrane cholesterol on the CCK receptors [35, 44].

Additionally, we discovered a new CRAC site on TM7 that overlaps with the highly conserved class A GPCR NPxxY motif; subsequent sequence alignment with all 285 class A GPCRs showed that 38% share a CRAC sequence in this region (Supplementary Fig. S1). Tyr7.53 of the NPxxY motif plays an essential role in class A GPCR activation, as mutation of Tyr7.53 on numerous receptors has shown a decrease or elimination of downstream signaling [50]. Upon ligand binding, conformational changes in the transmembrane helices result in the formation of a water-mediated hydrogen-bond network that links Tyr7.53 to Tyr5.58. This interaction helps facilitate the outward swing of helix VI which in turn allows for the Gα subunit to bind the receptor and activate the signaling cascade [50]. The importance of both the NPxxY motif and cholesterol in GPCR physiology have been extensively supported in the literature and it is well established that the NPxxY motif plays a significant role in stabilizing active state receptors [50]. Our mutations on the β2AR reinforce the importance of this region in receptor stability and function as mutations to Y326A7.53 and F336Ahelix8 nearly abolished expression of the protein (Table 1).

Our LCP-Tm assay on the unmutated receptor showed that incorporating 10% cholesterol into the host lipid increased the Tm by 1.71 ± 0.85°C. F3217.48 is located on TM7 three amino acids above the novel CRAC sequence. We expected that mutating this residue (F321A) would alter cholesterol binding at this location and would thus decrease the ΔTm value in the LCP-Tm assay. However, our ΔTm value of 0.46 ± 0.77 °C from the unmutated receptor was not found to be statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval (p = 0.1310). R3287.55 is a key part of the CRAC sequence outlined above. Like our F321A mutation, we hypothesized that the R328A mutation would inhibit cholesterol interactions and lower the ΔTm value of the receptor. Surprisingly, the R328A mutant’s Tm value increased from 44.39 ± 0.76 to 50.14 ± 1.47°C with the addition of cholesterol, yielding a ΔTm 5.75 ± 1.65 °C. This result was found to be significant at a 95% confidence interval (p=0.0194). This result is counterintuitive as we expected that the positively charged arginine residue should interact favorably with the hydroxyl group of cholesterol molecules, and thus the R328A mutation would result in a smaller ΔTm than the unmutated control. CGMD simulations of the mutant receptor did not show a significantly increased binding of cholesterol compared to WT, although the large standard deviations of the residence times leaves open the possibility that with much longer sampling times (well in excess of 100 μs) more subtle effects might be discovered. In the absence of reliable molecular data we may speculate that the ΔTm of R328A could be explained by the physical impact of cholesterol on lipid bilayers [21, 51, 52]. A mismatch between the length of the hydrophobic transmembrane helix and the width of the lipid bilayer is known to destabilize proteins [47] (an effect that cannot be captured by the MARTINI CG model because of its inherent secondary structure restraints). Hypothetically, these physical changes in the bilayer upon the addition of cholesterol could place the charged arginine residue into an environment that destabilizes the receptor (i.e., deeper into the hydrophobic membrane). Therefore, mutation to alanine would remove the potentially destabilizing effect of the charged arginine in the bilayer. Nevertheless, the difference in the experimental ΔTm values between the R328A mutant and the unmutated control were found to be statistically significant. Although our results from the biochemical assay and simulations were unexpected, and do not definitively show cholesterol binding at this CRAC, the data does suggest that R3287.55 may affect the receptor’s behavior in a membrane with modulated cholesterol levels. Additionally, studies have shown that mutation of this CRAC sequence at the type-1 cannabinoid receptor inhibited the cholesterol sensitivity of the receptor [5], which may support the importance of this CRAC sequence in other receptors besides the β2AR and the CCKRs.

It should be noted that CRAC sequences, as well as CCM and other cholesterol-recognition motifs, provide little predictive value in how cholesterol will interact with the protein [17, 53]. CRAC sequences are ubiquitous in membrane proteins and the presence of a CRAC sequence does not ensure cholesterol binding. A case for this can be seen in our simulation data as the CCK receptors, though containing CRAC sequences in various locations (TM3, TM5, and TM7), were not found to bind cholesterol at all of these locations. Instead, cholesterol molecules may have an affinity for the region surrounding a CRAC sequence as the correct hydrophobic, aromatic, and polar groups are in place to facilitate protein-cholesterol interactions [16, 17, 53], and in some cases, these interactions can have profound physiological effects.

Our study has shown that cholesterol interacts stronger with specific regions of cholesterol-sensitive receptors compared to their insensitive homologs. These data imply that specific receptor-cholesterol interactions play an important role in the modulation of receptors as a function of membrane cholesterol content. More detailed experimentation to determine the conformational changes associated with cholesterol binding would be very helpful in understanding these phenomena. We have identified a CRAC sequence that is conserved at the bottom of TM7 in 38% of class A GPCRs. Due to its overlap with the NPxxY motif, it is interesting to hypothesize that receptor-cholesterol interactions at TM7 could play an important role in cholesterol-mediated modulation throughout this family and detailed studies on other cholesterol sensitive receptors could yield more information. Additionally, downstream signaling assays could shed light on how these CRAC sequences affect receptor function. Regarding the CCK subfamily, our data agrees with previously published literature and could be helpful in the development of allosteric modulators to treat metabolic syndrome and obesity.

Materials and Methods:

Model Preparation and Simulations

Models for CCK1R and CCK2R were generated using Modeller [54, 55] with the orexin receptors 1 and 2 (OX1R and OX2R) as templates (PDB codes: OX1R: 4zj8 and 4zjc [72];OX2R: 4s0v [56], 5wqc and 5ws3 [57]). Fusion protein inserts were removed from the crystal structures and a multi-sequence alignment was performed using Jalview [58] with the CCK1R and CCK2R sequences (Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org) accession numbers P32238 and P32239, respectively) independently. Modeller was used to create twenty models for each protein and the structure with the lowest normalized DOPE score [59] for each was chosen (−0.52 and −0.40 for CCK1R and CCK2R, respectively). The system setup for the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) began with removing the T4-lysozyme fusion from the third intracellular loop (ICL3) in the crystal structure (PDB 2rh1 [73]). Modeller was used to fix the resulting gap in the structure by joining the short loop segments left after removing the insert. Using the CHARMM-GUI server [60], each of the three models was coarse-grained using the MARTINI force field [34, 61] with the ElNeDyn secondary structure restraints and inserted into a membrane. Two separate systems were created for each protein: one with a 1:4 cholesterol:1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) membrane (“20% cholesterol”) and one with a 2:3 cholesterol:POPC membrane (“40% cholesterol”). Coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) was performed using Gromacs 2019 [62] at 303.15 K and 1 bar using semiisotropic Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling [63] and stochastic velocity-rescale temperature coupling [64] with a 20 fs time step. A reaction-field with a 1.1 nm cutoff was used for the electrostatic interactions and a single cutoff of 1.215 nm was used for the van der Waal interactions [65]. Constraints were added according to the MARTINI force field [66]. Simulation lengths for each system are reported in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Run times for the simulations in microseconds (μs)

| 20% Cholesterol | β2AR | β2AR_R328A | CCK1R | CCK2R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 3 | 123.8 | 122.1 | ||

| Total | 366.2 | 363.7 | 100.3 | 103.3 |

| 40% Cholesterol | ||||

| Run 3 | 122.4 | 124.6 | ||

| Total | 364.8 | 366.4 | 101.3 | 81.1 |

Time series of the cholesterol-protein contacts were collected on a per residue basis for each trajectory using functionality in the MDAnalysis package [67], where a contact was defined with a 7 Å cutoff. Survival functions were calculated from a histogram of the waiting times for each residue. The survival functions were least-square-fitted with relative weights to a two-term hyperexponential with the form

| (1) |

using the curve_fit() function in SciPy [68]. Artifacts from the cutoff manifest themselves as spurious contacts with short waiting times, i.e., higher rates, so only the slower rates from the longer waiting times were taken to be indicative of cholesterol-protein interactions. Specifically, the slower of the two rates was used to calculate a mean waiting time τslow for each residue, termed the “residency time”, as

| (2) |

Further technical details on the methods will be published elsewhere (Sexton et al, in preparation). τslow was plotted against the residue number to compare mean waiting times across the protein using Matplotlib [69]. Errors for τslow values were obtained by dividing the trajectories into non-overlapping contiguous blocks of at least 20 μs and less than 21 μs and performing the contact analysis for each block. The mean and standard deviation were calculated from the τslow values over all blocks. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 – 13, a block length of ~20 μs provided a consistent picture compared to fewer but longer blocks and was chosen for its conservative (large) error estimate while still providing a sufficient number of events for the fitting procedure to converge. When we plotted residence times we only automatically labelled residues with a residence time at least three times greater than the overall background as computed by the mean over all residence times (excluding residues without data or with insufficient data for the hyperexponential fit to converge). The residence times for the CCK homologues were compared by performing a sequence alignment and taking the difference (CCK1R - CCK2R) of the τslow values obtained, which was called Δτ. The standard deviation of the difference was calculated from error propagation of the individual standard deviations of the τslow values. VMD [70] and Chimera [71] were used for molecular visualizations.

Mutant Receptor Preparation

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on β2AR using primers with internal mismatches (IDT) and Phusion polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mutant receptors were verified via Sanger sequencing (Genewiz). Receptors were expressed and purified as previously described [19]. Receptors were analyzed for total and surface expression on a Guava flow cytometer (Millipore). Purified receptors were analyzed for purity and homogeneity via analytical size exclusion chromatography. Homogeneous receptors were further analyzed using the LCP-Tm assay.

LCP-Tm Assay

Cholesterol binding to mutant receptors was quantified via a thermal denaturation assay in LCP as described [43]. Briefly, purified receptors were mixed in an approximately 35% (v/v) ratio with molten monoolein (Nu-check) containing either 0 or 10% cholesterol. Final protein concentrations were 0.015 mg/mL for each assay. Fluorescence signal was recorded using a Cary Eclipse Emission Spectrophotometer (Agilent). Background signal from a blank LCP sample was subtracted from the protein sample and the inner filter effect was corrected for as described [43]. CPM (7-Diethylamino-3-(4’-Maleimidylphenyl)-4-Methylcoumarin (Sigma)) probe was added to the protein at a final concentration of 0.004 mg/mL and allowed to incubate on ice, and in the dark, for 30 minutes before incorporation into the LCP matrix. The excitation wavelength for fluorescence was 387 nm and emissions were recorded via scanning between 400 and 500 nm with a step size of 1 nm. Mathematical fitting and statistics were carried out in Prism version 8.3.1(GraphPad) as described [43]. The effects of cholesterol were quantified as the change in denaturation temperature as a function of the addition of cholesterol into the LCP matrix. ΔTm values for mutant receptors were compared to an unmutated control.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The Cholecystokinin receptors bind cholesterol specifically and differentially.

Interactions at F1303.41 may cause cholesterol sensitivity at the CCK1R.

A newly discovered CRAC sequence is conserved across 38% of class-A GPCRs.

The conserved CRAC sequence overlaps the highly conserved NPxxY motif on TM7.

LCP-Tm assay supports the importance of this CRAC sequence at the β2AR.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1R15GM124623-01A (O.B.), the National Institutes of Health grants R21DA042298 (W.L.) and R01GM124152 (W.L.), the STC Program of the National Science Foundation through BioXFEL (No. 1231306; W.L.), a Mayo Clinic ASU Collaborative Seed Grant Award (W.L.), and the Flinn Foundation Seed Grant (W.L.) The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Fredriksson R, Lagerström MC, Lundin L- G, Schiöth HB. The G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in the Human Genome Form Five Main Families. Phylogenetic Analysis, Paralogon Groups, and Fingerprints. 2003;63(6):1256–72. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256 %J Molecular Pharmacology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2017;16(12):829–42. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villar VAM, Cuevas S, Zheng X, Jose PA. Chapter 1 - Localization and signaling of GPCRs in lipid rafts. In: Shukla A K, editor. Methods in Cell Biology. 132: Academic Press; 2016. p. 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paila YD, Jindal E, Goswami SK, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol depletion enhances adrenergic signaling in cardiac myocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2011;1808(1):461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oddi S, Dainese E, Fezza F, Lanuti M, Barcaroli D, De Laurenzi V, et al. Functional characterization of putative cholesterol binding sequence (CRAC) in human type-1 cannabinoid receptor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2011;116(5):858–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pucadyil TJ, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol modulates ligand binding and G-protein coupling to serotonin1A receptors from bovine hippocampus. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2004;1663(1):188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pucadyil TJ, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol modulates the antagonist-binding function of hippocampal serotonin1A receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2005;1714(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimpl G, Burger K, Fahrenholz F. Cholesterol as Modulator of Receptor Function. Biochemistry. 1997;36(36):10959–74. doi: 10.1021/bi963138w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimpl G, Wiegand V, Burger K, Fahrenholz F. Chapter 4 Cholesterol and steroid hormones: modulators of oxytocin receptor function. Progress in Brain Research. 139: Elsevier; 2002. p. 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. In: Sealfon SC, editor. Methods in Neurosciences. 25: Academic Press; 1995. p. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khelashvili G, Grossfield A, Feller SE, Pitman MC, Weinstein H. Structural and dynamic effects of cholesterol at preferred sites of interaction with rhodopsin identified from microsecond length molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins. 2009;76(2):403–17. doi: 10.1002/prot.22355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benned-Jensen T, Norn C Fau - Laurent S, Laurent S Fau - Madsen CM, Madsen Cm Fau - Larsen HM, Larsen Hm Fau - Arfelt KN, Arfelt Kn Fau - Wolf RM, et al. Molecular characterization of oxysterol binding to the Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene 2 (GPR183). (1083–351X (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Byrne EFX, Sircar R, Miller PS, Hedger G, Luchetti G, Nachtergaele S, et al. Structural basis of Smoothened regulation by its extracellular domains. (1476–4687 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Luchetti G, Sircar R, Kong JH, Nachtergaele S, Sagner A, Byrne EF, et al. Cholesterol activates the G-protein coupled receptor Smoothened to promote Hedgehog signaling. Elife. 2016;5:e20304. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sensi C, Daniele S, Parravicini C, Zappelli E, Russo V, Trincavelli ML, et al. Oxysterols act as promiscuous ligands of class-A GPCRs: in silico molecular modeling and in vitro validation. (1873–3913 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bukiya AN, Dopico AM. Common structural features of cholesterol binding sites in crystallized soluble proteins. 2017;58(6):1044–54. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R073452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fantini J, Barrantes F. How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013;4:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimpl G Interaction of G protein coupled receptors and cholesterol. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 2016;199:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Griffith MT, Roth CB, Jaakola V- P, Chien EYT, et al. A Specific Cholesterol Binding Site Is Established by the 2.8 A Structure of the Human beta2-adrenergic Receptor. Structure. 2008;16(6):897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafurulla M, Aditya Kumar G, Rao BD, Chattopadhyay A. A Critical Analysis of Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Membrane Cholesterol Sensitivity of GPCRs. In: Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Bukiya AN, editors. Cholesterol Modulation of Protein Function: Sterol Specificity and Indirect Mechanisms. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 21–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper RA. Influence of increased membrane cholesterol on membrane fluidity and cell function in human red blood cells. Journal of Supramolecular Structure. 1978;8(4):413–30. doi: 10.1002/jss.400080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nezil FA, Bloom M. Combined influence of cholesterol and synthetic amphiphillic peptides upon bilayer thickness in model membranes. biophysical Journal 61(0006–3495 (Print)):1176–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Rand RP. The influence of cholesterol on phospholipid membrane curvature and bending elasticity. (0006–3495 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pal S, Chakraborty H, Bandari S, Yahioglu G, Suhling K, Chattopadhyay A. Molecular rheology of neuronal membranes explored using a molecular rotor: Implications for receptor function. Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2016;196:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soubias O, Gawrisch K. The role of the lipid matrix for structure and function of the GPCR rhodopsin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2012;1818(2):234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ingólfsson HI, Lopez CA, Uusitalo JJ, de Jong DH, Gopal SM, Periole X, et al. The power of coarse graining in biomolecular simulations. WIREs Computational Molecular Science. 2014;4(3):225–48. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stansfeld PJ, Sansom MSP. Molecular simulation approaches to membrane proteins. Structure. 2011;19(11):1562–72. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedger G, Sansom MSP. Lipid interaction sites on channels, transporters and receptors: Recent insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2016;1858(10):2390 – 400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta D, Chattopadhyay A. Molecular dynamics simulations of GPCR–cholesterol interaction: An emerging paradigm. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2015;1848(9):1775 – 82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genheden S, Essex JW, Lee AG. G protein coupled receptor interactions with cholesterol deep in the membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2017;1859(2):268 – 81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jafurulla M, Tiwari S, Chattopadhyay A. Identification of cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif in G-protein coupled receptors. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2011;404(1):569–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasanna X, Chattopadhyay A, Sengupta D. Cholesterol modulates the dimer interface of the β2 -adrenergic receptor via cholesterol occupancy sites. Biophysical journal. 2014;106(6):1290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouviere E, Arnarez C, Yang L, Lyman E. Identification of Two New Cholesterol Interaction Sites on the A\textsubscript2A Adenosine Receptor. Biophysical Journal. 2017;113(11):2415 – 24. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Periole X, Cavalli M, Marrink S- J, Ceruso MA. Combining an Elastic Network With a Coarse-Grained Molecular Force Field: Structure, Dynamics, and Intermolecular Recognition. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2009;5(9):2531–43. doi: 10.1021/ct9002114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter RM, Harikumar KG, Wu SV, Miller LJ. Differential sensitivity of types 1 and 2 cholecystokinin receptors to membrane cholesterol. 2012;53(1):137–48. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desai AJ, Lam PCH, Orry A, Abagyan R, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, et al. Molecular Mechanism of Action of Triazolobenzodiazepinone Agonists of the Type 1 Cholecystokinin Receptor. Possible Cooperativity across the Receptor Homodimeric Complex. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;58(24):9562–77. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller LJ, Desai AJ. Metabolic Actions of the Type 1 Cholecystokinin Receptor: Its Potential as a Therapeutic Target. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2016;27(9):609–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller LJ, Holicky EL, Ulrich CD, Wieben ED. Abnormal processing of the human cholecystokinin receptor gene in association with gallstones and obesity. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(4):1375–80. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cang X, Du Y, Mao Y, Wang Y, Yang H, Jiang H. Mapping the Functional Binding Sites of Cholesterol in β2-Adrenergic Receptor by Long-Time Molecular Dynamics Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2013;117(4):1085–94. doi: 10.1021/jp3118192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee AG. Interfacial Binding Sites for Cholesterol on G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Biophysical Journal. 2019;116(9):1586–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirzadegan T, Benkö G, Filipek S, Palczewski K. Sequence Analyses of G-Protein-Coupled Receptors: Similarities to Rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 2003;42(10):2759–67. doi: 10.1021/bi027224+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pándy-Szekeres G, Munk C, Tsonkov TM, Mordalski S, Harpsøe K, Hauser AS, et al. GPCRdb in 2018: adding GPCR structure models and ligands. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;46(D1):D440–D6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1109 %J Nucleic Acids Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, Hanson MA, Stevens RC, Cherezov V. LCP-Tm: An Assay to Measure and Understand Stability of Membrane Proteins in a Membrane Environment. Biophysical Journal. 2010;98(8):1539–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai AJ, Harikumar KG, Miller LJ. A Type 1 Cholecystokinin Receptor Mutant That Mimics the Dysfunction Observed for Wild Type Receptor in a High Cholesterol Environment. 2014;289(26):18314–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.570200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heydenreich FM, Vuckovic Z, Matkovic M, Veprintsev DB. Stabilization of G protein-coupled receptors by point mutations. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2015;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roth CB, Hanson MA, Stevens RC. Stabilization of the Human β2-Adrenergic Receptor TM4–TM3–TM5 Helix Interface by Mutagenesis of Glu1223.41, A Critical Residue in GPCR Structure. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;376(5):1305–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Webb RJ, East JM, Sharma RP, Lee AG. Hydrophobic Mismatch and the Incorporation of Peptides into Lipid Bilayers: A Possible Mechanism for Retention in the Golgi. Biochemistry. 1998;37(2):673–9. doi: 10.1021/bi972441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez KM, Kang G Fau - Wu B, Wu B Fau - Kim JE, Kim JE. Tryptophan-lipid interactions in membrane protein folding probed by ultraviolet resonance Raman and fluorescence spectroscopy. Biophysical Journal. 100:2121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sansom MS, Bond Pj Fau - Deol SS, Deol Ss Fau - Grottesi A, Grottesi A Fau - Haider S, Haider S Fau - Sands ZA, Sands ZA. Molecular simulations and lipid-protein interactions: potassium channels and other membrane proteins. (0300–5127 (Print)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Ragnarsson L, Andersson Å, Thomas WG, Lewis RJ. Mutations in the NPxxY motif stabilize pharmacologically distinct conformational states of the α1B- and β2-adrenoceptors. Science Signaling. 2019;12(572):eaas9485. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aas9485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cherezov V, Clogston J, Misquitta Y, Abdel-Gawad W, Caffrey M. Membrane Protein Crystallization In Meso: Lipid Type-Tailoring of the Cubic Phase. Biophysical Journal. 2002;83(6):3393–407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75339-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raffy S, Teissié J. Control of Lipid Membrane Stability by Cholesterol Content. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76(4):2072–80. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baier CJ, Fantini J, Barrantes FJ. Disclosure of cholesterol recognition motifs in transmembrane domains of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Scientific Reports. 2011;1(1):69. doi: 10.1038/srep00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fiser A, Do RKG, Šali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Science. 2000;9(9):1753–73. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Šali A, Blundell TL. Comparative Protein Modelling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1993;234(3):779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin J, Mobarec JC, Kolb P, Rosenbaum DM. Crystal structure of the human OX2 orexin receptor bound to the insomnia drug suvorexant. Nature. 2015;519(7542):247–50. doi: 10.1038/nature14035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suno R, Kimura KT, Nakane T, Yamashita K, Wang J, Fujiwara T, et al. Crystal Structures of Human Orexin 2 Receptor Bound to the Subtype-Selective Antagonist EMPA. Structure. 2018;26(1):7–19.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1189–91. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eramian D, Eswar N, Shen M- Y, Sali A. How well can the accuracy of comparative protein structure models be predicted? Protein Science. 2008;17(11):1881–93. doi: 10.1110/ps.036061.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi Y, Ingólfsson HI, Cheng X, Lee J, Marrink SJ, Im W. CHARMM-GUI Martini Maker for Coarse-Grained Simulations with the Martini Force Field. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2015;11(9):4486–94. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Jong DH, Singh G, Bennett WFD, Arnarez C, Wassenaar TA, Schäfer LV, et al. Improved Parameters for the Martini Coarse-Grained Protein Force Field. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2013;9(1):687–97. doi: 10.1021/ct300646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. Journal of Applied Physics. 1981;52(12):7182–90. doi: 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bussi G, Donadio D Fau - Parrinello M, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. Journal of Chemical Physics 126(1). doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Jong DH, Baoukina S, Ingólfsson HI, Marrink SJ. Martini straight: Boosting performance using a shorter cutoff and GPUs. Computer Physics Communications. 2016;199:1 – 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2015.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monticelli L, Kandasamy SK, Periole X, Larson RG, Tieleman DP, Marrink S-J. The MARTINI Coarse-Grained Force Field: Extension to Proteins. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2008;4(5):819–34. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gowers ML RJ, Barnoud J, Reddy TJE, Melo MN, Seyler SL, Dotson DL, Domanski J, Buchoux S, Kenney IM, and Beckstein O. . MDAnalysis: A Python package for the rapid analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. . Proceedings of the 15th Python in Science Conference,. 2016:98/105. doi: 10.25080/majora-629e541a-00e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods. 2020;17(3):261–72. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hunter JD. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science Engineering. 2007;9(3):90–5. doi: 10.1109/MCSE.2007.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14(1):33–8. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(13):1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yin J, Mobarec JC, Kolb P, Rosenbaum DM, Crystal structure of the human OX2 orexin receptor bound to the insomnia drug suvorexant, Nature 2015;519(7542):247–250, 10.1038/nature14035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SGF, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi H-J, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, and Stevens RC, “High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor,” Science, vol. 318, pp. 1258–1265, November 2007. 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.