Abstract

Study Objectives:

To explore the association of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) adherence with clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea in a real-world setting.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of patients with type 2 diabetes diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea between 2010 and 2017. CPAP adherence (usage for ≥ 4 h/night for ≥ 70% of nights) was determined from the first CPAP report following the polysomnography. Data including estimated glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin A1c, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lipid panel, and incident cardiovascular/peripheral vascular/cerebrovascular events were extracted from medical records. Mixed-effects linear regression modeling of longitudinal repeated measures within patients was utilized for continuous outcomes, and logistic regression modeling was used for binary outcomes. Models were controlled for age, sex, body mass index, medications, and baseline levels of outcomes.

Results:

Of the 1,295 patients, 260 (20.7%) were CPAP adherent, 318 (24.5%) were CPAP nonadherent, and 717 (55.3%) had insufficient data. The follow-up period was, on average, 2.5 (1.7) years. Compared to those who were CPAP nonadherent, those who were adherent had a significantly lower systolic blood pressure (β = −1.95 mm Hg, P = .001) and diastolic blood pressure (β = −2.33 mm Hg, P < .0001). Among the patients who were CPAP adherent, a 17% greater CPAP adherence was associated with a 2 mm Hg lower systolic blood pressure. Lipids, hemoglobin A1c, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and incident cardiovascular/peripheral vascular/cerebrovascular events were not different between the 2 groups.

Conclusions:

Achieving CPAP adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea was associated with significantly lower blood pressure. Greater CPAP use within patients who were adherent was associated with lower systolic blood pressure.

Citation:

Sheth U, Monson RS, Prasad B, et al. Association of continuous positive airway pressure adherence with complications in patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(8):1563–1569.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, continuous positive airway pressure, compliance, blood pressure, eGFR, hemoglobin A1c

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Continuous positive airway pressure treatment has previously been associated with a reduction in blood pressure and possibly with a slower progression of chronic kidney disease in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. However, data are lacking on the association of continuous positive airway pressure treatment, especially adherence, with clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes in a real-world setting.

Study Impact: Achieving continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes with obstructive sleep apnea was associated with significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, while no associations were found with kidney function, lipids, glycemic control, or cardiovascular events. Greater continuous positive airway pressure use among patients who were adherent was associated with lower systolic blood pressure, suggesting a dose-response relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of complete or partial obstruction of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in intermittent hypoxemia, fragmented sleep, increased oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation. OSA has been linked to increased blood pressure, insulin resistance, incident diabetes, and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). 1–4 In patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), OSA is very prevalent, up to 86% in those with obesity. 4,5 Evidence suggests that patients with T2D with OSA may experience higher rates of complications than those without OSA, including coronary artery disease and stroke 6,7 and microvascular complications (eg, diabetic nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy). 8–10

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is an efficacious therapy for OSA. CPAP use has been shown to improve CVD risk factors, including blood pressure and insulin resistance in the general population, although the effects on cardiovascular events were mixed. 11–14 In patients with T2D with OSA, the effects of CPAP on glycemic control from multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with durations between 1 and 6 months, have been mixed. 15–17 A few RCTs found that CPAP treatment for 3–6 months resulted in a significant reduction in blood pressure (systolic 4–10 mm Hg and diastolic 3–7 mm Hg) in T2D; however, long-term studies are lacking. 17–19 Small observational studies have also investigated the effects of CPAP on diabetic microvascular complications. For example, in moderate to severe OSA, 16 patients with T2D and who were CPAP adherent were observed to have a significantly slower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline over an average of 2.5 years than 31 patients who were nonadherent. 20 Another retrospective cross-sectional study in veterans with T2D and OSA found that diabetic retinopathy was more prevalent in patients who were CPAP nonadherent (n = 110) compared to those who were adherent (n = 211). 21 Collectively, early limited evidence suggests that CPAP use in T2D may be beneficial for blood pressure control and in reducing diabetic vascular complications. However, longer-term data in a larger number of patients with specific consideration of objective CPAP adherence data are lacking.

One key obstacle to consider is the lack of adherence with CPAP treatment, which likely has an impact on outcomes. CPAP nonadherence rates are 30%–40% in nonresearch environments, despite measures taken to increase comfort and convenience. 15 Thus, there exists a gap of knowledge concerning the long-term effects of CPAP treatment incorporating objective adherence data in T2D with OSA on less-studied outcomes including diabetic complications and cardiovascular risk factors. This study aimed to investigate the association of CPAP adherence with clinical outcomes in patients with T2D and OSA utilizing longitudinal data obtained from a real-world setting. Primary outcomes of interest were blood pressure and eGFR during the follow-up period. Other outcomes of interest included lipid levels, glycemic control, and incident CVD. We hypothesized that patients with T2D and OSA who were CPAP adherent would have better clinical outcomes.

METHODS

Study population

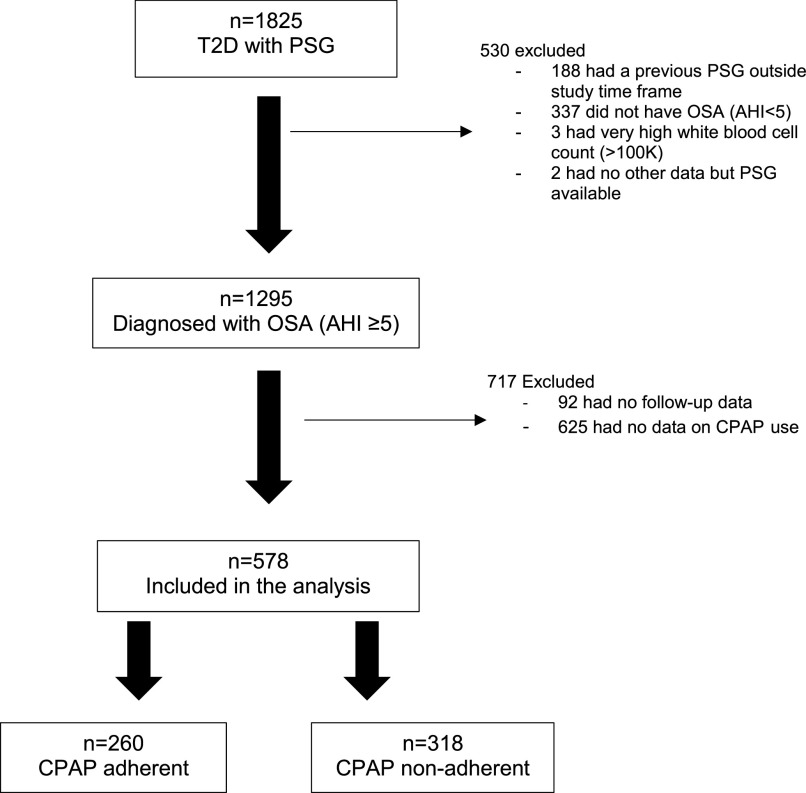

This study is a retrospective review of medical records between January 2010 and December 2017 (average follow-up of 2.5 years). It includes a cohort of adult patients (ages ≥ 18 years) with T2D who underwent attended in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) at the Sleep Science Center, University of Illinois. A diagnosis of T2D was identified using the International Classiciation of Diseases, Ninth and 10th Revisions, while PSG was identified using the Current Procedural Terminology code. This analysis focused on patients diagnosed with OSA with available CPAP use data during a follow-up period ( Figure 1 ). OSA was defined as an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 events/h on PSG.

Figure 1. Study cohort.

CPAP adherence = CPAP use ≥ 4 hours, ≥ 70% of nights. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index (events/h), CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, PSG = polysomnography, T2D = type 2 diabetes.

PSG and CPAP adherence data

The results of the PSG were extracted from medical records. The main variable was the AHI. Other variables included the number of minutes spent under the oxygen saturation of 90% during the recordings, as well as minimum oxygen saturation and arousal index. Data on CPAP usage were extracted from the first download from a newly issued CPAP device during the follow-up at the Sleep Science Center. The downloaded period typically was between 30 and 90 days after initiation of CPAP per the standard clinical practice. CPAP adherence, either obtained remotely or from the device microchip, was defined as ≥ 4 hours usage for ≥ 70% of nights. 22 The first download after initiation of CPAP was considered to be reflective of long-term use. 23,24

Demographics and laboratory data

Demographic information including age at PSG and sex were collected. The following data were collected longitudinally until December 30, 2017: (1) weight, height, and body mass index; (2) systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP); (3) number of antihypertensive medications, including the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers; (4) number of antidiabetic medications, including the use of insulin; (5) use of lipid-lowering agents; (6) laboratory data: complete blood count, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), eGFR, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low density lipoprotein; and (7) history of PSG and incident diagnoses of CVD, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular accident per International Classification of Diseases codes.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Skewed data were log transformed, and influential outliers were excluded. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations or frequencies and percentages) were performed prior to modeling. Baseline data were defined as the average across all data points within 1 year prior to PSG, with 90% being within 6 months prior to PSG. Outcome variables were limited to those collected after the index PSG date. Baseline characteristics were respectively compared between adherent and nonadherent CPAP users using the Student t test (with log transformation of variables when appropriate, but raw data presented) or chi-square. As some outcome data included repeated measures, mixed-effects linear regression was used for repeating continuous outcome variables, while logistic regression was used for nonrepeating binary outcomes. Variables controlled for in all models were body mass index, age at PSG, sex, number of diabetes medications ever used, and insulin use ever. Baseline blood pressures, baseline eGFR, number of hypertension medications ever used, history of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers use specifically, and use of lipid-lowering medications ever were additionally controlled for in selected models (ie, baseline eGFR controlled for in eGFR model). There were too few pre-PSG lipid and HbA1c values to adjust those models for baseline levels. See Table 2 footnotes for specific details.

Table 2.

Differences in outcomes by CPAP adherence.

| Betaa | P | CPAP-Adherent | CPAP-Nonadherent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People With Data (n) | Total Observations (n) | People With Data (n) | Total Observations (n) | |||

| Renal function testsb,c | ||||||

| eGFRd (log) (mL/min/1.73 m2) | –0.03 | .48 | 109 | 438 | 136 | 651 |

| eGFRd ≥ 60 (log) (mL/min/1.73 m2) | –0.03 | .32 | 76 | 220 | 95 | 322 |

| eGFRd ≥ 30 (log) (mL/min/1.73 m2) | –0.05 | .10 | 101 | 374 | 123 | 527 |

| Blood pressureb,e | ||||||

| SBPd (mm Hg) | –1.95 | .001 | 183 | 3,053 | 215 | 3,910 |

| DBPd (mm Hg) | –2.33 | < .0001 | 183 | 3,052 | 215 | 3,906 |

| Lipidsb,f | ||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | –1.22 | .86 | 65 | 97 | 90 | 149 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 0.43 | .94 | 62 | 93 | 88 | 141 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 3.34 | .06 | 64 | 95 | 89 | 148 |

| Triglycerides (log) (mg/dL) | –0.16 | .07 | 64 | 95 | 89 | 147 |

| Glycemic controlb | ||||||

| HbA1c (log) (%) | –0.01 | .73 | 39 | 47 | 59 | 88 |

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Number of Events | Number of Events | |||

| Incidence of vascular diseaseb,e,f | ||||||

| CVD | 1.13 (0.63–2.02) | .68 | 27 | 34 | ||

| PVD | 1.05 (0.54–2.03) | .89 | 19 | 26 | ||

| CVA | 0.85 (0.41–1.79) | .68 | 14 | 23 | ||

aBeta: CPAP-adherent—CPAP-nonadherent. bAdjusted for BMI, age at time of PSG, sex, number of diabetes medications ever used, any history of insulin use. cAdjusted for any history of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use. dAdjusted for baseline value of outcome. eAdjusted for number of hypertension medications ever used. fAdjusted for any history of lipid medication use. BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, CVA = cerebrovascular accident, CVD = cardiovascular disease, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c, HDL = high-density lipoprotein, LDL = low-density lipoprotein, PSG = polysomnography, PVD = peripheral vascular disease, SBP = systolic blood pressure.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the study cohort. Of the 1,825 patients with a diagnosis of T2D who had a PSG between 2010 and 2017, 1,295 were diagnosed with OSA. Of these, 578 patients had sufficient CPAP follow-up data. Two hundred sixty patients (45.0%) were adherent with CPAP, while 318 patients (55.0%) were not adherent. Characteristics between patients with and without sufficient CPAP follow-up data were similar, with the exception that those without sufficient follow-up data had a lower AHI (mean [standard deviation] 39.7 (35.6) vs 45.6 [35.6], P = .003), were more likely to be using insulin (64.4% vs 57.8%, P = .02), and were less likely to have peripheral vascular disease at baseline (8.5% vs 13.0%, P = .01).

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the cohort with sufficient CPAP follow-up data, which were typical of patients with T2D. The mean ages of CPAP-adherent and CPAP-nonadherent groups were 55.4 and 54.9 years, respectively. Almost 70% were taking oral diabetes medications, while almost 80% were taking lipid-lowering therapy. Approximately one-fourth to one-third had a history of CVD at baseline. There were no significant differences between those who were CPAP adherent and nonadherent in age, sex, baseline blood pressure, eGFR, HbA1c, lipid values, comorbidities, or PSG findings. However, those who were CPAP nonadherent were more likely to be using insulin compared with participants who were CPAP adherent (62.9% vs 51.6%, P = .01) and more likely to be using antihypertensive agents (93.4% vs 88.2%, P = .04).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| CPAP-Adherent (n = 260) | CPAP-Nonadherent (n = 318) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Female sex, n (%) | 137 (52.7) | 176 (55.3) | .52 |

| Age at PSG (y) | 55.4 (11.0) | 54.9 (11.7) | .54 |

| Vitals/laboratory results | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 41.2 (9.0), n = 247 | 41.8 (9.8), n = 301 | .53 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 136 (17), n = 194 | 136 (17), n = 226 | .70 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 76 (10), n = 194 | 77 (10), n = 226 | .18 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 75.8 (28.6), n = 177 | 78.0 (32.1), n = 223 | .93 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.4 (1.6), n = 88 | 7.6 (2.0), n = 113 | .50 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 171 (44), n = 96 | 173 (44), n = 135 | .80 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 101 (40), n = 94 | 99 (35), n = 131 | .71 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 42 (13), n = 96 | 44 (11), n = 135 | .31 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 142 (77), n = 96 | 154 (88), n = 135 | .47 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| CVD | 71 (27.3) | 102 (32.1) | .21 |

| PVD | 32 (12.3) | 43 (13.5) | .67 |

| CVA | 31 (11.9) | 42 (13.2) | .64 |

| Medication history, n (%) | |||

| Insulin | 127 (51.6), n = 246 | 190 (62.9), n = 302 | .01 |

| ACEI or ARB | 139 (56.5), n = 246 | 180 (59.6), n = 302 | .46 |

| Lipid medication | 192 (78.0), n = 246 | 230 (76.2), n = 302 | .60 |

| Oral T2D medication | 171 (69.5), n = 246 | 202 (66.9), n = 302 | .51 |

| Anti-HTN medication | 217 (88.2), n = 246 | 282 (93.4), n = 302 | .04 |

| Sleep data | |||

| AHI (events/h) | 48.1 (36.8) | 43.9 (34.6) | .16 |

| T90 (min) | 25.6 (36.8), n = 247 | 23.2 (32.4), n = 312 | .33 |

| Min O2 (%) | 75.9 (11.9), n = 256 | 75.5 (11.8), n = 317 | .71 |

| Arousal index | 25.3 (20.4), n = 230 | 23.0 (18.9), n = 286 | .08 |

| Follow-up (y) | 2.5 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.7) | .98 |

ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI = body mass index, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, CVA = cerebrovascular accident, CVD = cardiovascular disease, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c, HDL = high-density lipoprotein, HTN = hypertension, LDL = low-density lipoprotein, Min O2 = minimum oxygen saturation, PSG = polysomnography, PVD = peripheral vascular disease, SBP = systolic blood pressure, T90 = time spent under an oxygen saturation of 90%, T2D = type 2 diabetes, TG = triglycerides.

Table 2 compares outcomes between the CPAP-adherent and CPAP-nonadherent groups, adjusted for multiple covariates after an average follow-up of 2.5 years. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were significantly lower during follow-up in patients who were CPAP adherent vs CPAP nonadherent (SBP = −1.95 mm Hg, P = .001 and DBP = −2.33 mm Hg, P < .0001), based on 6,963 and 6,958 observations, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates mean SBP during follow-up among baseline CPAP-use groups. Further exploration of data from patients who were adherent revealed that a 17% greater CPAP adherence was associated with a 2 mm Hg lower SBP, adjusted for age at PSG, sex, body mass index, baseline SBP, and number of hypertension medications. With regard to other variables, HDL tended to be higher (+3.34 mg/dL, P = .06, 283 HDL measurements) and TG tended to be lower (−0.16 mg/dL [log], P = .07, 242 TG measurements) in the CPAP-adherent group compared with the nonadherent group. However, there were no significant differences in eGFR, cholesterol, HbA1c, or incident CVD/peripheral vascular disease/cerebrovascular accident between these 2 populations, although the number of observations for some of these variables was relatively small.

Figure 2. Mean SBP during follow-up by baseline CPAP use.

Mean SBP (mm Hg) during follow-up among CPAP use groups (baseline CPAP average use [hours/day]). Note that the total sample size is 411, slightly larger than the 398 included in the adjusted analysis ( Table 2 ), due to a few missing covariates in some participants in the final analysis. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, SBP = systolic blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of patients with T2D and OSA, we aimed to explore if CPAP adherence is associated with better cardiometabolic outcomes, over an average follow-up of 2.5 years. We found that CPAP adherence was associated with significantly lower SBP by 1.95 mm Hg and DBP by 2.33 mm Hg. In addition, a 17% greater CPAP adherence in those who were adherent was associated with a 2 mm Hg lower SBP, suggesting a dose-response relationship. The associations with HDL and TG were borderline, with a trend for higher HDL (+3.34 mg/dL, P = .06) and lower TG (P = .07). However, this study did not reveal a relationship between CPAP adherence and eGFR, glycemic control, or incidence of cardiovascular events. The current study demonstrates the beneficial effects of CPAP adherence on blood pressure among patients with T2D and OSA in real-world clinical practice.

Our findings concerning blood pressure confirm results from studies in the general population, with a similar effect size. In a meta-analysis of 7 RCTs, CPAP use, compared to no CPAP or sham CPAP, was associated with significant reductions in 24-hour ambulatory SBP of 2.32 mm Hg and DBP of 1.98 mm Hg, with more significant improvement in nocturnal SBP than in diurnal SBP. 25 The magnitude of reduction in blood pressure in our study is clinically significant as the data from the Framingham Heart Study revealed that a 2 mm Hg lower DBP was associated with a 15% reduction in cerebrovascular accident and transient ischemic attacks. 26 However, the magnitude of the difference in blood pressure in our study is less than that found in a short-term RCT of CPAP treatment in T2D with OSA. Lam et al 17 investigated the use of 3 months of CPAP in 61 obese patients with T2D and at least moderate OSA (AHI ≥ 15 events/h) and found a significant decrease in SBP and DBP of 10 mm Hg and 6 mm Hg, respectively. However, when analyzing the results without patients who changed antihypertensive therapy during the study, the authors found that only the change in DBP remained significant. 17 The average CPAP usage in this study was only 2.5 ± 2.3 hours a night, and only 37.5% were adherent. In another RCT of patients with T2D newly diagnosed moderate OSA, Myhill et al 19 reported a reduction in SBP and DBP of approximately 9 mm Hg and 7 mm Hg, respectively, after 3 months of CPAP use (averaging 5.4 hours/night). In another retrospective cohort of 221 veterans with newly diagnosed OSA and either diabetes or hypertension being treated with either CPAP or automatic positive airway pressure, there was a significant reduction in blood pressure at a 9- to 12-month follow-up appointment (SBP = −6.81 mm Hg, DBP = −3.69 mm Hg). 27 Our study, focusing only on patients who had CPAP adherence data with a longer follow-up from real-world data, strengthens these findings. Our results further suggest a dose-response relationship between greater CPAP adherence and lower blood pressure. These highlight the importance of CPAP adherence in patients with T2D.

Our study did not show a significant difference in eGFR in patients with T2D who were adherent with CPAP at all levels of baseline eGFR. The retrospective nature of our study did not allow the capture of all factors that could impact chronic kidney disease in patients with T2D, so our results should be interpreted with caution. Some data exist regarding CPAP use and eGFR in the general population. For example, in 1 small prospective study of 27 men with OSA (AHI ≥ 20 events/h), CPAP use for 3 months showed an increase in eGFR from 72.9 to 79.3 mL/min/1.73 m2, although there was no control group. 28 A more recent prospective study of 269 patients with stage 3 or stage 4 chronic kidney disease found that 12 months of CPAP significantly reduced the rate of eGFR decline in both mild and moderate/severe OSA. 29 These data were based on 52 patients who were CPAP adherent. The data in patients with T2D, however, are scarce. In a 2.5-year longitudinal study of patients with T2D with OSA, 16 patients who were CPAP-adherent with moderate/severe OSA had a significantly slower rate of eGFR decline compared with 31 patients who were nonadherent with moderate/severe OSA (7.7% vs 10.0%). 10 It is clear that we need more prospective data in a larger population to determine the effects of CPAP on the progression of chronic kidney disease in this patient group.

Other outcomes in this study, including serum lipids, glycemic control, and incidence of cardiovascular disease, were not different between groups, although there was a favorable trend in lipid profile with adherence (higher HDL and lower TG). The number of observations of HbA1c and the utilization of diagnoses documented in the medical records might have influenced these results. A meta-analysis of 6 RCTs in the general population revealed that CPAP use was associated with decreased total cholesterol, but had no effect on TG, low-density lipoproteins, and HDL. 30 In our study, there was no significant difference in HbA1c between the CPAP-adherent and nonadherent groups. In multiple RCTs, CPAP use between 1 and 6 months showed inconsistent effects on HbA1c in patients with T2D. 15–17 The heterogeneous results could be partly due to differences in adherence, background glycemic control, and antidiabetic medication use. A retrospective case-control study in 300 patients with T2D and OSA from the United Kingdom found that after 5 years of CPAP therapy, HbA1c levels were significantly lower in those who used CPAP compared to those who did not (8.2% vs 12.1%). 31 The benefit was seen by the second year of CPAP and was maintained thereafter. Note that the adherence data were only available for 11 out of the 139 patients on CPAP in this study. Finally, we did not find a significant difference in incident cardiovascular events between the CPAP-adherent vs nonadherent groups, although the number of events was low and the full detail of cardiovascular disease management was not available. However, the same result was also obtained by the SAVE trial, in which 2,717 patients from the general population with moderate to severe OSA and established cardiovascular disease were randomized to receive CPAP therapy or usual care. 32 The duration of the follow-up was 3.7 years, and an average CPAP adherence was 3.3 hours/night. 32 The study did not find significant differences between the 2 groups in cardiovascular outcomes, including cardiovascular death, incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, heart failure, or transient ischemic attack. 32 These similar results suggest that CPAP, despite lowering blood pressure significantly, might not affect cardiovascular outcomes, at least within the duration of the studies.

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature as mentioned. The CPAP adherence data were limited to the first visit only, which could have changed subsequently, although data support that initial use is similar to long-term use. 23,24 In addition, there was a significant number of patients who were diagnosed with OSA but did not have CPAP data in the medical records. It was unclear if these patients received care elsewhere or never started CPAP treatment. Those with missing CPAP data were significantly more likely to be on insulin at baseline, had a lower AHI, and had less prevalent peripheral vascular disease than the included cohort. How this might affect outcomes is unknown. Furthermore, we did not include a potential moderator of blood pressure response to CPAP treatment such as the Epworth Sleepiness Score 33 as it was inconsistently recorded. The number of observations for certain outcomes (eg, lipids, HbA1c, and cardiovascular disease) was small; thus, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn. It is possible that participants with worse baseline glycemic control benefited more from CPAP therapy, but the number of HbA1c observations in this subgroup was too small to conduct a meaningful subgroup analysis. The exact details of their diabetes medication, eg, insulin dose, also were not readily available. The strength of our study is the inclusion of patients with T2D only and a relatively large sample size. Moreover, these results were obtained from a real-world, clinical setting in a longitudinal fashion, suggesting that these outcomes are likely to be seen in clinical practice. It is also alarming that only 44.9% of the participants were adherent with CPAP. This, however, was not different from previous data in the general population. 34

In summary, this study demonstrated that patients with T2D and OSA who were CPAP adherent had lower blood pressure compared to those who were nonadherent. While eGFR and cardiovascular outcomes were not significantly different between the 2 groups, well-designed RCTs with adequate power and follow-up are required to address these important questions in patients with T2D and OSA.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the University of Illinois at Chicago. This study was funded by a grant from the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002003. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. B. Prasad is funded by 1IK2CX001026-01, Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development. S. Reutrakul received a speaker fee from Becton Dickinson, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Subhash Kumar Kolar Rajanna, Biomedical Informatics Core Center for Clinical and Translational Science, the University of Illinois at Chicago, for his assistance in the study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TG

triglycerides

REFERENCES

- 1. Hou H , Zhao Y , Yu W , et al . Association of obstructive sleep apnea with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis . J Glob Health . 2018. ; 8 ( 1 ): 010405 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Punjabi NM , Shahar E , Redline S , Gottlieb DJ , Givelber R , Resnick HE ; Sleep Heart Health Study Investigators . Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: the Sleep Heart Health Study . Am J Epidemiol . 2004. ; 160 ( 6 ): 521 – 530 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shahar E , Whitney CW , Redline S , et al . Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study . Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2001. ; 163 ( 1 ): 19 – 25 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reutrakul S , Mokhlesi B . Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetes: a state of the art review . Chest . 2017. ; 152 ( 5 ): 1070 – 1086 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster GD , Sanders MH , Millman R , et al . Sleep AHEAD Research Group . Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes . Diabetes Care . 2009. ; 32 ( 6 ): 1017 – 1019 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seicean S , Strohl KP , Seicean A , Gibby C , Marwick TH . Sleep disordered breathing as a risk of cardiac events in subjects with diabetes mellitus and normal exercise echocardiographic findings . Am J Cardiol . 2013. ; 111 ( 8 ): 1214 – 1220 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rice TB , Foster GD , Sanders MH , et al . Sleep AHEAD Research Group . The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and self-reported stroke or coronary heart disease in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus . Sleep . 2012. ; 35 ( 9 ): 1293 – 1298 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu Z , Zhang F , Liu Y , et al . Relationship of obstructive sleep apnoea with diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis . BioMed Res Int . 2017. ; 2017 : 4737064 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tahrani AA . Obstructive sleep apnoea in diabetes: does it matter? Diab Vasc Dis Res . 2017. ; 14 ( 5 ): 454 – 462 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tahrani AA , Ali A , Raymond NT , et al . Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetic nephropathy: a cohort study . Diabetes Care . 2013. ; 36 ( 11 ): 3718 – 3725 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Myllylä M , Hammais A , Stepanov M , Anttalainen U , Saaresranta T , Laitinen T . Nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease events in CPAP compliant obstructive sleep apnea patients . Sleep Breath . 2019. ; 23 ( 4 ): 1209 – 1217 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu J , Zhou Z , McEvoy RD , et al . Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis . JAMA . 2017. ; 318 ( 2 ): 156 – 166 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patil SP , Ayappa IA , Caples SM , Kimoff RJ , Patel SR , Harrod CG . Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment . J Clin Sleep Med . 2019. ; 15 ( 2 ): 301 – 334 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iftikhar IH , Hoyos CM , Phillips CL , Magalang UJ . Meta-analyses of the association of sleep apnea with insulin resistance, and the effects of CPAP on HOMA-IR, adiponectin, and visceral adipose fat . J Clin Sleep Med . 2015. ; 11 ( 4 ): 475 – 485 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morariu EM , Chasens ER , Strollo PJ Jr , Korytkowski M . Effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on glycemic control and variability in type 2 diabetes . Sleep Breath . 2017. ; 21 ( 1 ): 145 – 147 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martínez-Cerón E , Barquiel B , Bezos AM , et al . Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on glycemic control in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and Type 2 diabetes. A randomized clinical trial . Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016. ; 194 ( 4 ): 476 – 485 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam JCM , Lai AYK , Tam TCC , Yuen MMA , Lam KSL , Ip MSM . CPAP therapy for patients with sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes mellitus improves control of blood pressure . Sleep Breath . 2017. ; 21 ( 2 ): 377 – 386 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaw JE , Punjabi NM , Naughton MT , et al . The effect of treatment of obstructive sleep apnea on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes . Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016. ; 194 ( 4 ): 486 – 492 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Myhill PC , Davis WA , Peters KE , Chubb SA , Hillman D , Davis TM . Effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea . J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2012. ; 97 ( 11 ): 4212 – 4218 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tahrani AA , Ali A , Raymond NT , et al . Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetic neuropathy: a novel association in patients with type 2 diabetes . Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012. ; 186 ( 5 ): 434 – 441 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith JP , Cyr LG , Dowd LK , Duchin KS , Lenihan PA , Sprague J . The Veterans Affairs Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Use and Diabetic Retinopathy Study . Optom Vis Sci . 2019. ; 96 ( 11 ): 874 – 878 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Decision Memo for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (CAG-00093R2). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=204. Accessed June 25, 2020. .

- 23. Popescu G , Latham M , Allgar V , Elliott MW . Continuous positive airway pressure for sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: usefulness of a 2 week trial to identify factors associated with long term use . Thorax . 2001. ; 56 ( 9 ): 727 – 733 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Budhiraja R , Parthasarathy S , Drake CL , et al . Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy . Sleep . 2007. ; 30 ( 3 ): 320 – 324 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu X , Fan J , Chen S , Yin Y , Zrenner B . The role of continuous positive airway pressure in blood pressure control for patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) . 2015. ; 17 ( 3 ): 215 – 222 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cook NR , Cohen J , Hebert PR , Taylor JO , Hennekens CH . Implications of small reductions in diastolic blood pressure for primary prevention . Arch Intern Med . 1995. ; 155 ( 7 ): 701 – 709 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prasad B , Carley DW , Krishnan JA , Weaver TE , Weaver FM . Effects of positive airway pressure treatment on clinical measures of hypertension and type 2 diabetes . J Clin Sleep Med . 2012. ; 8 ( 5 ): 481 – 487 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koga S , Ikeda S , Yasunaga T , Nakata T , Maemura K . Effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure on the glomerular filtration rate in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome . Intern Med . 2013. ; 52 ( 3 ): 345 – 349 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li X , Liu C , Zhang H , et al . Effect of 12-month nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy for obstructive sleep apnea on progression of chronic kidney disease . Medicine (Baltimore) . 2019. ; 98 ( 8 ): e14545 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu H , Yi H , Guan J , Yin S . Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on lipid profile in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Atherosclerosis . 2014. ; 234 ( 2 ): 446 – 453 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guest JF , Panca M , Sladkevicius E , Taheri S , Stradling J . Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure to manage obstructive sleep apnea in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.K . Diabetes Care . 2014. ; 37 ( 5 ): 1263 – 1271 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McEvoy RD , Antic NA , Heeley E , et al . SAVE Investigators and Coordinators . CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea . N Engl J Med . 2016. ; 375 ( 10 ): 919 – 931 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yorgun H , Kabakçi G , Canpolat U , et al . Predictors of blood pressure reduction with nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and prehypertension . Angiology . 2014. ; 65 ( 2 ): 98 – 103 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russell T . Enhancing adherence to positive airway pressure therapy for sleep disordered breathing . Semin Respir Crit Care Med . 2014. ; 35 ( 5 ): 604 – 612 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]