To the Editor:

Turnout rates from recent U.S. elections reveal voting is important to older adults. In November 2020, 74% of adults 65 years and older voted. 1 By comparison, 69% of adults aged 35‐ to 64‐year‐old and 57% of adults 18‐ to 34‐year‐old cast ballots. 1 This high turnout among older adults was not just a one‐time occurrence; in 2018, a nonpresidential election year, 65% of older women and 68% of older men voted. 2

Since 2016, Penn Medicine has acknowledged the connection between voting and health and supported nonpartisan initiatives to expand patient voting access. Through voting, patients are able to express views on candidates and issues that impact their health. 3 For example, a vote for a particular candidate could affect health insurance options for an older adult, and a vote against zoning for a factory could prevent pollutants from entering their environment.

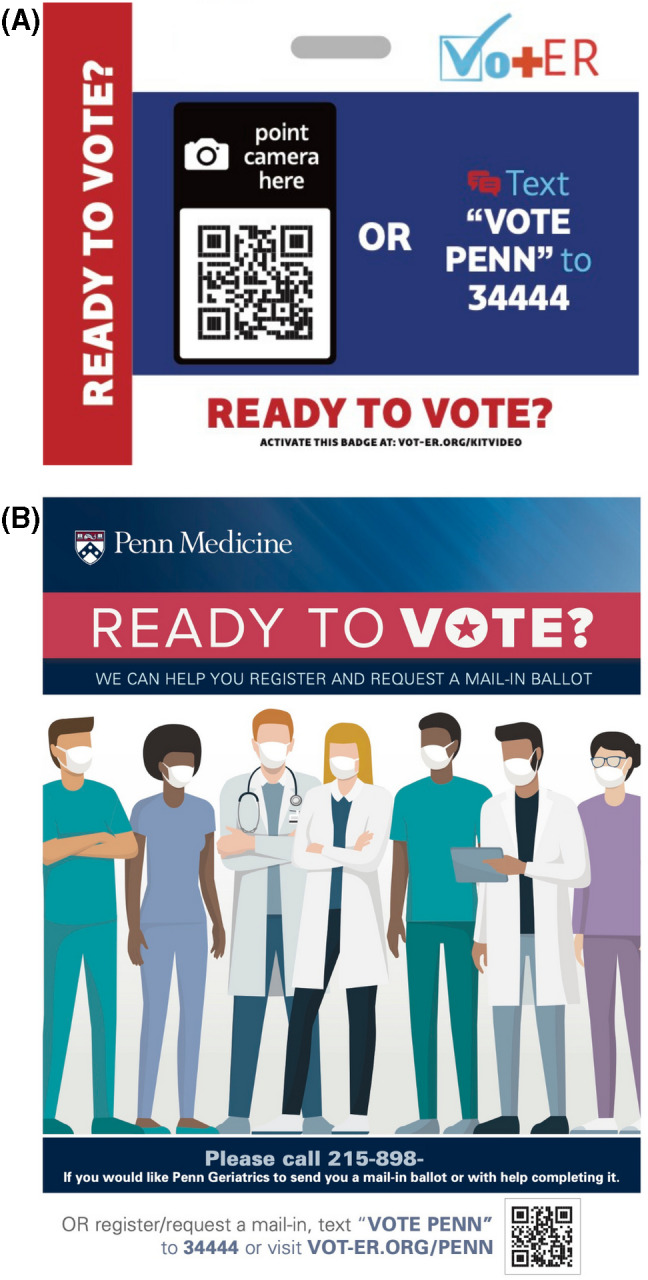

In August 2020, Penn Medicine also recognized the importance of promoting safe voting during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and partnered with Vot‐ER, a nonpartisan nonprofit dedicated to increasing voting access, 4 , 5 to offer clinicians badge backers featuring a QR code that linked to an online voter registration platform (Figure 1A). Interested clinicians used the badge backers to prompt nonpartisan discussions about the voter registration process with patients, who could then scan the QR code with their smartphones and register to vote and/or request a mail‐in ballot if they felt the latter provided a safer alternative to voting in person.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Institution‐specific Vot‐ER badge backer with a QR code that linked to an online voter registration platform. Clinicians could use these badge backers to prompt nonpartisan discussions with patients about registering to vote and voting safely. Interested patients could scan the QR code with their smartphones to access the platform and register to vote and/or request a mail‐in ballot. (B) Flyer mailed to all Penn Medicine Division of Geriatrics patients residing in Pennsylvania in September 2021. Prior to printing the flyer, we inadvertently omitted “application” after “If you would like Penn Geriatrics to send you a mail‐in ballot.” Although a small number of patients called and requested a mail‐in ballot, we provided clarifications over the phone and sent them a mail‐in ballot request application instead

We in the Division of Geriatric Medicine eagerly joined this initiative because our patients faced and continue to face the highest risks of developing and dying from severe COVID‐19. 6 Additionally, Pennsylvania law had just established no‐excuse mail‐in voting in October 2019, 7 making it unlikely all older adults would be aware of this option. However, we soon learned many of our patients lacked a smartphone and home internet connection, which prohibited them from accessing the online platform. With older adults making up nearly 19% of Pennsylvania's population 8 and over 75% of older adults in the state registering to vote in 2019 using paper applications, 9 we realized we needed to modify the existing campaign to meet the needs of our patient population. [Correction added after first online publication on December 07, 2021. The word ‘article’ has been replaced with the word ‘paper’].

Thus, we assembled a team of geriatricians, a retired social worker, and medical students. The geriatricians modified an existing flyer to include a phone number for the division and text offering assistance with voter registration and mail‐in ballot applications (Figure 1B). While we considered including a phone number for a national, nonpartisan election protection hotline, trial calls by one geriatrician revealed long wait times and short call times, which could be challenging for older adults requiring complex assistance. The medical students then repurposed student organization funds allocated for in‐person events prior to the pandemic to print copies of the flyer and volunteers mailed them to all of our patients in Pennsylvania more than a month before the state's voter registration deadline in October.

Patients who called the division phone number could leave a message on a voicemail system that automatically transcribed and e‐mailed the message to one of our geriatricians. That geriatrician or the retired social worker then returned each call within 72 hours and posted voter registration and/or mail‐in ballot applications to patients as needed.

Between mid‐September and mid‐October, we heard from 56 patients. Most asked for information on how to vote by mail, applications for mail‐in ballots for themselves and family, and assistance with checking the status of an application. Several patients stated they felt comfortable calling because they were confident the division would provide accurate and unbiased information.

It is our hope that sharing these experiences will encourage other health systems and geriatricians to consider the link between voting and health and the importance of helping older adults vote safely. Though this patient population consistently demonstrates high civic engagement, it faces disproportionate risks of developing and dying from severe COVID‐19. And although vaccines have helped reduce morbidity and mortality nationwide, 6 the pandemic remains far from over, and the next Election Day is quickly approaching.

As trusted sources of information, geriatricians can discuss with their patients plans for safe voting, including getting vaccinated, masking, social distancing, and considering voting by mail where available and if eligibility criteria are met—much like they already ask about seat belt and smoke detector use and firearm safety as part of the social history. By doing so, geriatricians can help prevent the spread of COVID‐19 and ensure older adults continue to have a say in the matters that affect their health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lesley S. Carson and Lisa M. Walke conceived and supervised the project. Yoonhee P. Ha, Lesley S. Carson, and Lisa M. Walke secured funding, recruited volunteers, and implemented the project. Yoonhee P. Ha and Lisa M. Walke conceived the letter. Yoonhee P. Ha and Sonia Gupta Pandit drafted the letter, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. Zonía R. Moore prepared the images for publication.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

The sponsor does not have a role in the preparation of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Debra Goldstein, Nancy O'Reilly, Carter Greist, Rudmila Rashid, Victoria Lord, Krista Moore, Alister Martin, volunteers with the Penn Medicine Division of Geriatric Medicine, Penn Medicine Votes, Physician Advocacy and Social Medicine, and Vot‐ER for their assistance with this project. Yoonhee P. Ha was supported by the Medical Scientist Training Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Yoonhee P. Ha and Sonia Gupta Pandit are co‐first authors.

Funding information Medical Scientist Training Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Fabina J. Record High Turnout in 2020 General Election. United Census Bureau (online). Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/record‐high‐turnout‐in‐2020‐general‐election.html

- 2. Misra J. Behind the 2018 U.S. Midterm Election Turnout. United States Census Bureau (online). Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/behind‐2018‐united‐states‐midterm‐election‐turnout.html

- 3. Ehlinger EP, Rita Nevarez C. Safe and accessible voting: the role of public health. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):45–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin A, Raja A, Meese H. Health care‐based voter registration: a new kind of healing. Int J Emerg Med. 2021;14(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12245-021-00351-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruxin TR, Ha YP, Grade MM, Brown R, Lawrence C, Martin AF. The Vot‐ER healthy democracy campaign: a national medical student competition to increase voting access. Acad Med. 2021. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Division of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . COVID‐19 Risks and Vaccine Information for Older Adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (online). Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html

- 7.Governor Wolf Signs Historic Election Reform Bill Including New Mail‐in Voting. Governor Tom Wolf (online). Accessed September 16, 2021. https://www.governor.pa.gov/newsroom/governor‐wolf‐signs‐election‐reform‐bill‐including‐new‐mail‐in‐voting/

- 8.Pennsylvania ‐ US Census Bureau QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau (online). Accessed January 12, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PA

- 9. Pennsylvania Department of State . The Administration of Voter Registration in Pennsylvania: 2019 Report to the General Assembly. https://www.dos.pa.gov/VotingElections/OtherServicesEvents/VotingElectionStatistics/Documents/AnnualReportsonVoterRegistration/2019AnnualReport.pdf