Conflicts of interest

All authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding source

None declared.

Editor

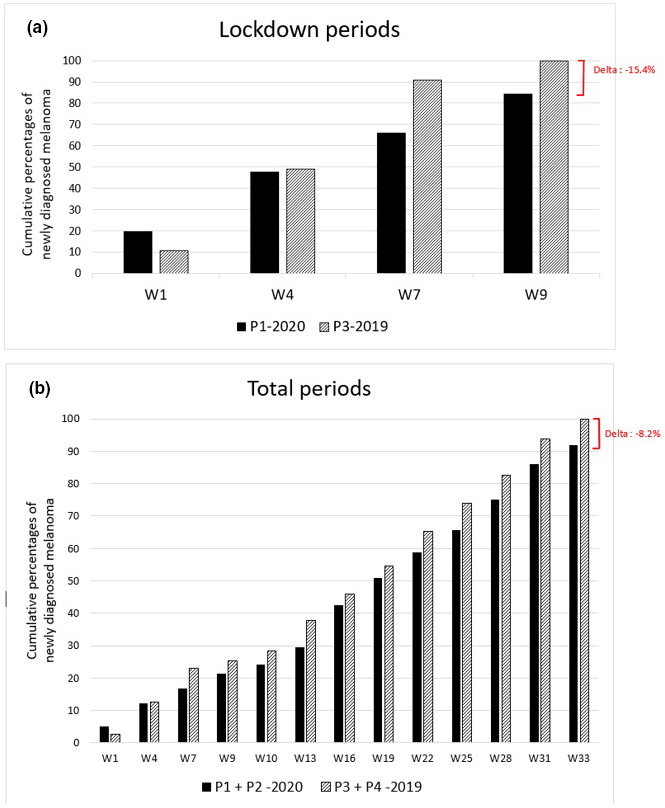

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the healthcare system worldwide, which led to a decrease in the number of melanoma diagnosis, 1 but the consequences of lockdown on newly diagnosed melanomas’ severity have not been widely reported. We aimed to evaluate how the first lockdown in France impacted the incidence and prognostic characteristics of new melanomas, in our skin cancer centre in the Parisian region, highly affected by the pandemic. We conducted a retrospective study including all new diagnosed melanoma referred to our centre, divided into 4 periods: P1 = 2020 lockdown period (17/03‐12/05/2020), P2 = 2020 post‐lockdown period (13/05‐31/10/2020), P3 = 2019 equivalent lockdown period (17/03‐12/05/2019), P4 = 2019 equivalent post‐lockdown period (13/05‐31/10/2019). We evaluated the differences in American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging, Breslow index, ulceration and lymph node (LN) involvement, using logistical regression models, adjusted according to age, gender, performance status, lifestyle, phototype and tumour‐infiltrating lymphocytes. Statistical tests were two‐sided and p‐values<5.0% was considered statistically significant. We included 493 consecutive new melanoma cases, with no difference in baseline patient characteristics between groups. Globally, we observed an 8.2% reduction of new cases in 2020 (P1 + P2) compared with 2019 (P3 + P4) and a 15.4% reduction during lockdown (P1) compared with P3 (Fig. 1). Melanomas diagnosed during P1 had a significantly higher mean Breslow index than during P3 (1.7 mm ± 2.1 vs. 1.5 ± 2.5, P < 0.001). More interestingly, P2 and P4 comparison showed significantly more severe cases at diagnosis after lockdown (P2), both on Breslow index, ulceration and neurotropism than on the AJCC stages (Table 1). Sentinel LN biopsy or LN dissection were more frequently performed (57% vs. 38.5%, P < 0.001); significantly less patients without regional metastasis (i.e. N0) were observed (64.4% vs. 79.7%, P = 0.01) and clinically occult LN involvement (i.e. Nxa) was more frequent (13.5% vs. 5.4%, P = 0.01), leading to more patients with an indication for adjuvant therapy (12.0% vs. 4.7%, P = 0.01). Patients referred during P2 had a higher risk of having melanoma with both a Breslow index ≥ 0.8 mm (OR = 1.75, 95%CI [1.19–2.63], P = 0.006) and ulceration (OR = 1.69, 95%CI [1.05–2.80], P = 0.034), than during P4; the risk of having a LN involvement also seemed to be higher (but not significantly): OR = 1.58, 95%CI [0.99–2.59], P = 0.06. Some similar studies worldwide focusing on the effect on the pandemic on melanoma has also reported the reduction of new cases, 1 , 2 , 3 with increased thickness. 3 , 4 To note, although this reduction was lower in our study (35% 1 to 60% 2 vs. 15.4%), which might be due to different management between countries (our dermato‐oncological activity was kept at the same level throughout the pandemic), we observed significant differences in severity. Reduction in attendance observed during P1 has not been caught up during P3, (Fig. 1) suggesting a delayed impact beyond the study period, which is consistent with previous concerns about subsequent effects of delayed cancer diagnosis on morbi‐mortality. 5 , 6 , 7 To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate both prognostic factors and delayed impact of lockdown on melanoma AJCC 8th staging and adjuvant therapy on a large number of patients, compared to a reference period. We also evaluated the difference in adjuvant treatments, known to be responsible for adverse events and additional health costs. 8 This highlights the challenges of diagnostic strategies in skin cancer, 7 at a time of disputed mass screenings leading to overdiagnosis, 9 with consequences in terms of health cost and patients’ anxiety. 10 Prevention and early melanoma detection are still a cornerstone in melanoma management, and the future’s key challenge will be to find tools, such as teledermatology, to guarantee permanent access to melanoma screening, especially for high‐risk populations.

Figure 1.

Cumulative numbers of new melanoma cases in 2019 and 2020

Table 1.

Comparison of pathologic melanoma characteristics and proportion of melanoma stages according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition staging system between ‘2020 post‐lockdown’ (=P2) and ‘2019 reference post‐lockdown’ (=P4) periods

|

2020 post‐lockdown (P2) N = 181 |

2019 reference post‐lockdown (P4) N = 192 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AJCC 8th edition staging | |||

| In situ | 34 (19) | 36 (19) | 0.99 |

| Stage I | 87 (48) | 117 (61) | 0.01 |

| IA | 64 (35) | 93 (48) | 0.01 |

| IB | 23 (13) | 24 (13) | 0.95 |

| Stage II | 34 (19) | 25 (13) | 0.13 |

| IIA | 12 (7) | 13 (7) | 0.96 |

| IIB | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 0.90 |

| IIC | 14 (8) | 4 (2) | 0.01 |

| Stage III | 24 (13) | 11 (6) | 0.01 |

| IIIA | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.99 |

| IIIB | 8 (4) | 2 (1) | 0.06 |

| IIIC | 14 (8) | 6 (3) | 0.06 |

| IIID | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Stage IV | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.99 |

| Histological subtypes | |||

| SSM | 122 (67) | 133 (69) | 0.70 |

| Nodular | 23 (13) | 17 (9) | 0.23 |

| Acrolentiginous | 8 (4) | 6 (3) | 0.59 |

| LM/LMM | 24 (13) | 26 (14) | 0.94 |

| Mucosal | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.50 |

| Unclassifiable | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 0.29 |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.99 |

| Breslow index mean, mm (±SD) | 2.2 (±2.4) | 1.6 (±2.8) | <0.001 |

| Presence of ulceration | 41 (23) | 18 (9) | 0.001 |

| Presence of mitoses | 58 (32) | 49 (26) | 0.32 |

| Presence of regression | 10 (6) | 11 (6) | 0.73 |

| Presence of neurotropism | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.007 |

| Presence of angiotropism | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.68 |

P: Student or Wilcoxon tests for quantitative/continuous variables, Chi‐Square or Fisher tests for qualitative/categorical variables (R‐studio Version 1.2.5033). Numbers (percentage).

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma; LM, lentigo maligna; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; SD, standard deviation.

R. Molinier and A. Roger contributed equally to this work.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Javor S, Sola S, Chiodi S, Brunasso AMG, Massone C. COVID‐19‐related consequences on melanoma diagnoses from a local Italian registry in Genoa, Italy. Int J Dermatol 2021; 60: e336–e337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barruscotti S, Giorgini C, Brazzelli V et al. A significant reduction in the diagnosis of melanoma during the COVID‐19 lockdown in a third‐level center in the Northern Italy. Dermatol Ther 2020; 33: e14074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ricci F, Fania L, Paradisi A et al. Delayed melanoma diagnosis in the COVID‐19 era: increased Breslow thickness in primary melanomas seen after the COVID‐19 lockdown. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: jdv.16874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shannon AB, Sharon CE, Straker RJ et al. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the presentation status of newly diagnosed melanoma: a single institution experience. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 1096–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tejera‐Vaquerizo A, Nagore E. Estimated effect of COVID‐19 lockdown on melanoma thickness and prognosis: a rate of growth model. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e351–e353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Manoli S‐M et al. Delayed skin cancer diagnosis in 2020 because of the COVID‐19–related restrictions: Data from an institutional registry. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: 721–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dessinioti C, Garbe C, Stratigos AJ. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on diagnostic delay of skin cancer: a call to restart screening activities. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35(12): jdv.17552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomolin T, Cline A, Handler MZ. The danger of neglecting melanoma during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Dermatol Treat 2020; 31: 444–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Welch HG, Mazer BL, Adamson AS. The rapid rise in cutaneous melanoma diagnoses. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Preventive Services Task Force , Bibbins‐Domingo K, Grossman DC et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 316: 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.