INTRODUCTION

Though the COVID‐19 pandemic has led to substantial decline in cancer screening rates, studies have not focused on older adults.1, 2, 3 Older adults are at higher risk for severe COVID‐19 infection and have been recommended to take extra caution to reduce exposure. Therefore, older adults may be more likely than younger adults to postpone cancer screening during the pandemic. The delay in screening and the pandemic experience as an unprecedented public health crisis may also have affected older adults' attitudes and intentions towards cancer screening. Better understanding the pandemic's impact on older adults' attitudes and intentions towards cancer screening can inform efforts to remedy negative effects from the pandemic and optimize post‐pandemic cancer screening practices.

METHODS

In a cross‐sectional survey (November 19, 2020–December 4, 2020) using a nationally representative online panel (KnowledgePanel – details in Supporting information), 4 we examined self‐reported screening behaviors and attitudes since the COVID‐19 pandemic for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screenings. Panel members aged 65 and older were invited to one of three survey versions by cancer type. The response rate was 72.2% (68.5% breast cancer, 73.8% colorectal cancer, 74.4% prostate cancer). Participants were categorized as choosing to “screen” or “delay”; “screen” included those who have been screened during the pandemic or were not due for screening but hypothetically would choose screening; “delay” included those who have delayed or would delay screening.

We asked about reasons for delaying screening, the impact of the pandemic on interest in screening and perceived value of screening, and intentions to resume screening. We collected information on demographics, political affiliation, a single‐item Medical Maximizer–Minimizer question (MM1), 5 perceived cancer risk, 6 enthusiasm towards cancer screening, 7 concern about COVID‐19, health literacy, 8 health/functional status which were used to predict 10‐year mortality risk, 9 and perceived safety of getting screening. We used national data to calculate county‐level COVID‐19 case rates 2 weeks before the study. 10 We used univariable and multivariable logistic regression to identify characteristics associated with choosing “screen” versus “delay”; due to sample size constraints, regression models pooled data across cancer types. Survey weights were applied to adjust for nonresponse.

RESULTS

Of 585 participants (breast cancer: 212 women; prostate cancer: 205 men; colorectal cancer: 84 women, 84 men), the majority were white (76.5%) with mean age 73.8 years; 30.0% perceived screening at the time of the survey to be less safe than pre‐pandemic (Table S1). Enthusiasm about cancer screening was high, among the 413 participants who had not already stopped screening, 69.1% agreed with screening for cancer for as long as one lives.

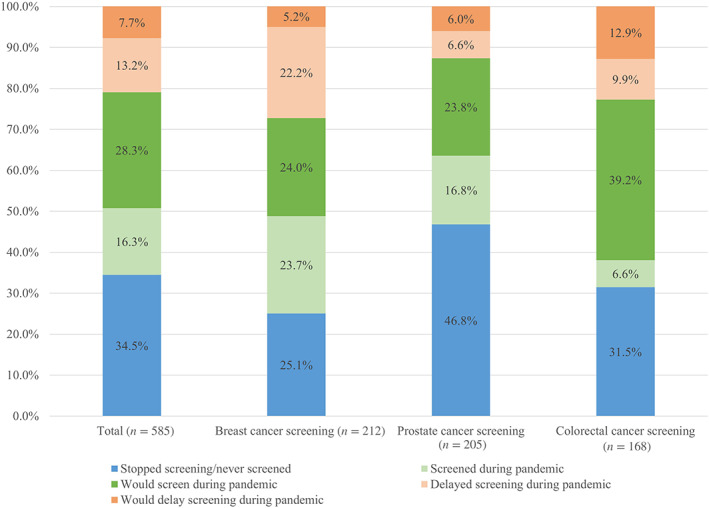

Overall, 293 (44.6%) participants either were screened (16.3%) or would choose screening (28.3%) during the pandemic whereas 120 (20.8%) participants either delayed (13.2%) or would delay screening (7.7%); the rest had stopped screening before the pandemic (Figure 1). In univariable models, age, predicted 10‐year mortality risk, race, education, health literacy, local COVID‐19 case rate, or concern about COVID‐19 were not significantly associated with choosing “screen” versus “delay,” whereas screening enthusiasm, perceived screening safety, and response to the MM1 were significantly associated with the outcome (Table S2). These three variables were then included in a multivariable model. High screening enthusiasm was associated with higher odds (odds ratio [OR] 1.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–3.00) of choosing “screen” versus “delay,” compared with lower levels of enthusiasm. Those who perceived that screening was same or more safe than pre‐pandemic were also more likely to choose “screen” versus “delay” (ORs 4.15 [95% CI 2.49–6.92] and 4.78 [95% CI 2.14–10.67]) compared with perceiving screening as less safe. Response to the MM1 no longer reached statistical significance in multivariable model.

FIGURE 1.

Older adults' self‐reported screening behaviors and intentions during the COVID‐19 pandemic

Among the 120 participants who delayed or would delay screening, the most common reasons were concern about COVID‐19 exposure (45.8%), not having seen the doctor during pandemic (21.1%), and not having thought about screening (15.5%). The majority (63.4%) of these planned to resume screening, 25.9% were neutral and 13 participants (10.8%) did not plan to resume screening.

Interest in screening and perceived value of screening were largely unchanged. Among the 413 participants who had not already stopped screening; 7.1% reported less interest in cancer screening long‐term, 11.1% reported more interest; 4.3% considered cancer screening less worthwhile than pre‐pandemic whereas 18.4% considered screening more worthwhile.

DISCUSSION

Despite studies describing decline in cancer screening rates earlier in the pandemic,1, 2, 3 for most older adults, the pandemic did not dampen interest in cancer screening and may enhance enthusiasm about cancer screening overall. One possible explanation is that the pandemic has highlighted the importance of health and health care. Given the numerous uncertainties during the pandemic, older adults may be more inclined to do what they can to optimize their health and cancer screening is one such action. It will be important to assess whether the findings persist long‐term.

For older patients who are appropriate candidates for cancer screening, our results suggest that clinicians can and should recommend continuing or resuming cancer screening without much worry about patient reluctance. Highlighting safety of screening may be important in counseling. In older patients for whom screening cessation is appropriate, clinicians should recognize that the enhanced screening enthusiasm may contribute to hesitancy about stopping screening and adapt discussion about screening cessation accordingly.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Pollack has stock ownership in Gilead Sciences, Inc. Dr. Cynthia Boyd received a small payment from UptoDate for having coauthored a chapter on multimorbidity. We do not believe any of the above has resulted in any conflict with the design, methodology, or results presented in this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Schoenborn had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Design of the study: Nancy L. Schoenborn, Cynthia M. Boyd, and Craig E. Pollack. Data analysis: Nancy L. Schoenborn. Data interpretation: Nancy L. Schoenborn, Cynthia M. Boyd, and Craig E. Pollack. Preparation of the manuscript: Nancy L. Schoenborn. Review and revision of the manuscript: Nancy L. Schoenborn, Cynthia M. Boyd, and Craig E. Pollack.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

This project was made possible by the K76AG059984 grant from the National Institute on Aging. In addition, Dr. Boyd was supported by 1K24AG056578 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting information.

Funding information National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: 1K24AG056578, K76AG059984

REFERENCES

- 1. Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh Q‐D. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:458‐460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. London JW, Fazio‐Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, Sankey P, McNair C. Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on cancer‐related patient encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:657‐665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:878‐884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ipsos . KnowledgePanel – a methodological overview. Accessed March 2021. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ipsosknowledgepanelmethodology.pdf

- 5. Scherer LD, Zikmund‐Fisher BJ. Eliciting medical maximizing–minimizing preferences with a single question: development and validation of the MM1. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(4):545‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Health Information National Trends Survey . Survey instruments. Accessed March 2021. https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Instruments/HINTS5_Cycle2_Annotated_Instrument_English.pdf

- 7. Lewis CL, Kistler CE, Amick HR, et al. Older adults' attitude about continuing cancer screening later in life: a pilot study interviewing residents of two continuing care communities. BMC Geriatr. 2006;5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561‐566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, Stijacic‐Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Predicting 10‐year mortality for older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(9):874‐876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The New York Times . Coronavirus (COVID‐19) data in the United States. Accessed January 14, 2021. https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting information.