Abstract

Rationale, Aims, and Objectives

Addressing wellbeing among learners, faculty, and staff during the COVID‐19 pandemic is a challenge for many clinical departments. Continued and systemic supports are needed to combat the pandemic's impact on mental health and wellbeing. This article describes an iterative approach to conducting a needs assessment and implementing a COVID‐19‐related wellness initiative in a psychiatry department.

Methods

Development of the initiative followed the Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) quality improvement cycle and was informed by Shanafelt and colleagues' framework for supporting healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Key features included the establishment of a Wellness Working Group, the curation of relevant resources on the Department's website, and the deployment of regular, monthly surveys that informed the creation of further supports, such as a weekly online drop‐in support group.

Results

Survey response rates ranged from 22% to 32% (n = 90‐127) throughout our initiative. Across multiple surveys, approximately 80% of respondents reported feeling supported or very supported by the Department, and 90% were satisfied or very satisfied with the quantity and quality of information provided. Our support group and resources page were accessed by nearly one‐quarter and one‐third of respondents, respectively, with satisfaction rates of 81% or higher. Consistent with the Department's mandate, ensuring equity was a key focus of the Working Group throughout its operations.

Conclusions

There is potential for this model to be scaled to create a faculty‐wide, institution‐wide, or regional approach to addressing wellbeing. Other departments may also wish to adopt similar approaches to supporting their members during this challenging time.

Keywords: evaluation, health services research, healthcare, medical research

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has placed an immense strain on healthcare systems around the world. Frontline clinicians have had to be nimble in adapting to a growing volume of patient care while coping with rapidly changing clinical guidelines and unfamiliar working environments. 1 Potential exposure to the virus has led to heightened anxiety around providing clinical care, and in some cases, moral distress and injury. 1 , 2 Physicians who are not on the front lines have also experienced disruption, with many having to transition to providing virtual or distanced care or contend with the possibility of redeployment. 3 In a study of healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic, specific concerns reported by physicians and other frontline healthcare workers included access to personal protective equipment, exposure to the virus at work and transmission to family members, inadequate access to testing, uncertainty about organizational support should they become ill, access to childcare, support for other personal and family needs, redeployment, and a lack of access to up‐to‐date information and communication. 4

Besides faculty, clinical departments at academic centres comprise diverse members from a multitude of professional backgrounds whose lives have also been altered by the pandemic. 5 Examples include researchers, whose research programs have been put on hold or who have had to pivot quickly to alternate forms of data collection; learners whose education has been rapidly transitioned to an online format; and support staff whose roles may have been changed or adjusted. Working conditions have dramatically changed as many individuals are now working from home where there may be less separation between work and personal time. 6

More than ever, the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic has reinforced the need for continued and systemic efforts to create a healthy workplace environment and facilitate wellbeing. 1 , 7 As one of the basic units of institutional organization, academic departments have a duty to support their members through times of difficulty. However, to date, much of the focus has been on adaptations to meet the needs of learners as opposed to faculty and staff. 5 Moreover, the acuity and rapid evolution of the COVID‐19 pandemic have likely made it challenging for some programs and departments to conduct needs assessments related to their members' psychological wellbeing and respond adequately to any identified concerns. These represent important gaps in both the literature and in practice that need to be addressed in order to ensure the sustainability of the healthcare and academic workforce during these challenging times.

In this article, we use the Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) quality improvement cycle 8 to describe an iterative approach to conducting a needs assessment and implementing a COVID‐19‐related wellness initiative in a psychiatry department. The overarching goal of our initiative was to maintain an up‐to‐date pulse on Department members' needs as they evolved throughout the pandemic, as well as to inform broader supports within the Department. Recognizing our role as a psychiatry department and anticipating significant and widespread mental health‐related issues due to COVID‐19, we felt a responsibility to be prepared, knowing that others could be looking to us to provide expertise. Mobilizing quickly was important given the rapid onset of the pandemic and the lack of an existing knowledge base to draw upon. In disseminating our approach to promoting departmental wellbeing during a global pandemic, we hope that other departments and institutions can use our experiences as a model to help inform needs assessments and support programs in their own contexts.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context

The Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences (DPBN) at McMaster University is a clinical department comprising approximately 400 members. The Department is home to clinical and non‐clinical learners and faculty, as well as a range of research and support staff. The DPBN has made a commitment to the deliberate fostering of wellbeing for all faculty, learners, and staff. Wellness is a key component of the Department's equity, diversity, and inclusivity (EDI) mandate, and is in the portfolio of the Vice‐Chair of the Department.

2.2. Evaluation framework

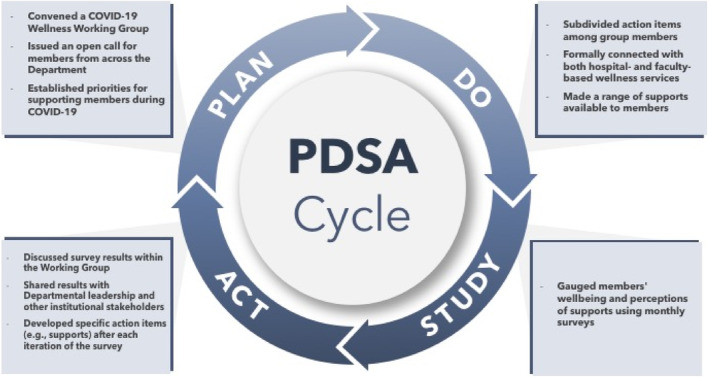

The PDSA cycle was originally conceptualized by Shewhart and Deming for application to quality improvement processes in industry. 8 Over the years, it has increasingly been applied to healthcare settings to address complex clinical problems in a systematic manner. 9 The model consists of four components (plan, do, study, act) that mirror the various stages of the scientific method. 8 We selected PDSA as our evaluation framework because of its focus on an iterative cycle of development, 8 an element we felt was critical to the success of our initiative (see Figure 1). A criticism of PDSA has been that reporting of initiatives tends to be vague and lacking in the contextual details needed to understand its effectiveness. 8 Thus, in writing this article, we used SQUIRE 2.0 as a guideline to ensure clear reporting and improve the ease with which our initiative can be adopted in other contexts. 10

Figure 1.

Schematic of the PDSA cycle as it applied to the development and deployment of the DPBN COVID‐19 Wellness Working Group

2.2.1. Plan

Shortly after the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, the DPBN quickly mobilized to convene a COVID‐19 Wellness Working Group. An open call for members was sent out, allowing all interested parties within the Department to take part. Initially, the group consisted of 17 members, including administrators, clinician‐educators in both psychology and psychiatry, learners, and PhD‐trained researchers, and met virtually on a weekly basis to establish a plan for supporting Department members during the pandemic. We decided early on that the deployment of monthly surveys to gauge departmental needs and the curation of a new resources page on the DPBN website would be core foci of the Working Group. Meetings also provided members with the opportunity to share site‐specific updates, discuss topics of interest (eg, news articles related to the pandemic), and recommend action items.

2.2.2. Do

We divided and distributed tasks among members with the available time and expertise, as Working Group members volunteered their time and did not have their workload reduced as a result of their participation. A core group of members trained in assessment and research methods worked together to produce drafts of the surveys, which were shared with other members for input. These questions were based on hypothesized issues of concern to Department members and were refined with each iteration of the survey. Another subgroup worked together to curate COVID‐19‐related resources for inclusion on the DPBN website, including communication updates, useful links from professional organizations, and articles on clinical practice, education, research, and wellbeing. Technical aspects of this work (ie, updating the website) were supported by administrative staff within the Department. Following the first set of survey results, we convened a weekly online drop‐in support group, which was facilitated by the Chair of the Working Group (also the DPBN Vice‐Chair), a senior resident, and on one occasion, a clinical psychologist. We also formally connected with both hospital‐ and faculty‐based wellness support services to ensure the coordination of resources.

2.2.3. Study

Regular, anonymous, web‐based surveys programmed in LimeSurvey and sent to all Department members via the DPBN listserv were critical for understanding members' needs as they evolved during the pandemic. Surveys were sent out approximately once every month for 3 months. In addition to evaluating members' level of satisfaction with the supports being offered and inviting suggestions for improvement, the surveys also provided a way of monitoring members' current stressors, levels of coping, and mental wellbeing using a combination of locally developed items and the Short Warwick‐Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale 11 (see [Link], [Link], [Link]). Each survey contained a mix of open‐ and closed‐ended response options and was kept relatively short (ie, 5 minutes) so as to maximize participation. As noted earlier, the survey was modified at each iteration to ensure that the topics remained relevant as departmental needs evolved. Certain questions (ie, related to coping, stressors, and wellbeing) were kept consistent to allow comparisons of responses across time.

2.2.4. Act

The results of each survey were summarized using descriptive statistics and taken back to the Working Group for discussion. They were subsequently shared with departmental leadership, who provided a high‐level summary at monthly Department meetings. Specific action items were developed following each survey, representing an iterative feedback loop. For example, the establishment of the support group was the direct result of a need identified by the first survey. As needs evolved and participation waned, the group was moved to a biweekly format and later put on hold. The Working Group continued to support Department members in other ways, such as by sharing links to online resources, other peer support groups, and telephone helplines.

2.3. Theoretical framework

In addition to the PDSA cycle, Shanafelt and colleagues' framework 4 for supporting healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic was used as a sensitizing concept 12 to help guide the development of our needs assessment and initiative from a theoretical perspective. This framework, which is based on evidence from listening sessions with 69 healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic, recommends the following five levels of support: hear me, protect me, prepare me, support me, and care for me. 4 Thus, our approach to supporting Department members during the COVID‐19 pandemic was designed to hear their concerns through an iterative data collection process; support members by offering a weekly online drop‐in support group and connecting them with relevant resources; and care for members by recognizing the broader challenges that they were facing during the pandemic (eg, related to childcare). In Shanafelt and colleagues' framework, 4 protecting and preparing are related to ensuring members' physical safety and providing rapid training to prepare members for the clinical care of patients during COVID‐19, which were not directly within the purview of our Working Group. Nonetheless, where possible, we attempted to connect Department members with the appropriate resources (eg, from our hospital partners) to help address these issues.

3. RESULTS

Survey response rates ranged from 22% to 32% (n = 90‐127) throughout our initiative. As shown in Table 1, a range of stressors was identified that ebbed and flowed throughout the course of the pandemic. Early concerns were mostly related to addressing clinical issues and providing safe patient care during COVID‐19, as well as the need for rapid information sharing. Department members, especially those with a role in clinical care, were concerned about contracting the virus and/or transmitting it to their families. As the pandemic waned on and safety protocols were established, fears around contracting and transmitting the virus became less pronounced and were replaced by the effects of a loss of routine/structure and difficulty maintaining productivity. Department members also reported being challenged by a loss of income due to reduced clinical loads, childcare issues, and loneliness. During the summer months, when there was a brief relaxation of pandemic restrictions, respondents reported concerns around return‐to‐work protocols and uncertainty about what the future would hold.

Table 1.

Key pandemic‐related concerns reported by participants

| March 2020 Survey (n = 127 respondents) | April 2020 Survey (n = 109 respondents) | May 2020 Survey (n = 90 respondents) |

|---|---|---|

|

Loss of routine/structure (57%) Difficulty maintaining productivity (53%) Loss of income (34%)

Fear of contracting COVID (30%) Loneliness (26%) Fear of passing on COVID (25%) Childcare issues (18%) Impact on academic career (11%) |

|

Across multiple surveys, approximately 80% of respondents felt supported or very supported by the Department, and 90% were satisfied or very satisfied with the quantity and quality of information provided. Nearly a quarter (23%; n = 15) reported attending the support group at least once, with an average of 3 to 12 participants per meeting. Close to a third (29%; n = 37) of respondents reported accessing the online resources page. Department members who made use of the aforementioned resources found them to be helpful (81% and 100%, respectively); however, even members who did not use them commented that they felt reassured knowing that supports were available should they be needed.

Supports evolved to remain current with Department members' needs during the pandemic. A detailed online resources page was created at the onset of the pandemic when the need for rapid information sharing was highest. The resources on this page were refined and condensed over time to ensure they remained up‐to‐date and reflective of the best available evidence. The support group was also most useful in the first few months of the pandemic, as it gave participants a chance to share emotions such as sadness, guilt, anger, loneliness, fear, and uncertainty, as well as experiences, such as the challenges with providing virtual care or difficulty dividing time between work and home. Participants also discussed silver linings, such as pleasures to look forward to and examples of resilience, self‐compassion, and renewed optimism. Facilitators encouraged participants to share strategies for managing wellbeing during the pandemic, some of which included making a schedule to support work‐family integration, starting a new hobby or making time to work on existing hobbies, humour, online games to play with friends and relatives at a distance, and healthy venting. Participants also discussed how they might help others during the pandemic and curated a list of community resources. Attendance at the support group waned approximately 6 months into the pandemic, at which time the Working Group decided to transition efforts into the provision of continued support in the form of relevant online resources, other peer support groups, and telephone helplines.

An unintended consequence of our approach to supporting departmental wellbeing during the COVID‐19 pandemic was that our surveys revealed not only concerns related to the pandemic, but also other departmental and societal issues affecting members' wellbeing. One example was the Black Lives Matter Movement, which had led to a renewed focus on EDI. In light of their importance, these issues became part of the conversations had by the Working Group. An area of focus was ensuring equity within the Working Group's own practices by expanding membership to include diverse voices, making supports available at multiple time points to increase accessibility, and coordinating with other groups aimed at promoting EDI in the Department such as the Indigenous Mental Health Working Group and the LGBTQ2S+ Working Group. We also provided Department members with individual support options (eg, online resources, telephone helplines) in case they were not comfortable accessing group‐based supports due to concerns about privacy and confidentiality.

4. DISCUSSION

This article used the PDSA quality improvement cycle 8 to describe an iterative approach to conducting a needs assessment and implementing a COVID‐19‐related wellness initiative in a psychiatry department. From a theoretical perspective, our approach was guided by Shanafelt and colleagues' framework 4 for supporting healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic, which consists of the following five levels of support: hear me, protect me, prepare me, support me, and care for me.

Overall, we consider our needs assessment and initiative to have been a success. While our survey response rates reflected only a quarter to a third of our Department, this engagement is higher than we have experienced with other Departmental initiatives and should be considered in light of the many demands on members' time, as well as the relaxation of pandemic restrictions in the summer months of 2020. The supports we provided were well received by those who responded to the survey, with some respondents noting that they did not experience this level of support from other Departments to which they are appointed. Furthermore, aside from Working Group members' time administrative support with respect to scheduling meetings and updating the website, this initiative was not associated with any other costs and may therefore be feasible to implement in lower‐resource settings.

Several contextual factors were important in ensuring the success of our initiative. Although the stressors uncovered during our needs assessment were similar to those reported in other articles, 4 , 7 the iterative nature of our approach identified how quickly needs could shift over time and helped ensure that supports remained relevant over time. Another factor that critical for ensuring success was the engagement of stakeholders in the dissemination of findings. Having senior leaders share the survey results and resulting action items at Department meetings showed members that their input was valued and contributed to their willingness to continue sharing their opinions in subsequent surveys. A third factor was the Working Group's coordination with other units, which helped streamline the provision of services and ensure the long‐term sustainability of our initiative. Finally, a number of Department members and support group members were licensed therapists, which was helpful for ensuring the success of the support group and coordinating with hospital‐ and faculty‐wide supports.

Like any initiative, ours is not without limitations. The Working Group felt that anonymous responses were the best way of ensuring that respondents would feel comfortable sharing their opinions; however, this meant that we were unable to track individual responses over time or to recommend individualized supports based on participants' responses. We attempted to mitigate this challenge by providing options for one‐on‐one support at the end of the surveys and through regular communication updates. Furthermore, it was not possible to gauge how representative our samples were of the Department as we did not collect demographic information for confidentiality reasons. We do not know if the characteristics of those who responded to the survey differed from those who did not respond.

Moreover, we recognize that some Department members did not access the supports provided (eg, the support group) because they did not feel comfortable sharing personal issues with colleagues. Our survey responses suggested that privacy and confidentiality were a concern among fewer than 20% of respondents; however, these issues are nonetheless important and remain a topic of ongoing discussion within the Working Group. Finally, it is possible that departments without access to trained facilitators or whose institutions do not actively promote mental health may find it more challenging to implement initiatives of a similar nature.

Next steps for the Working Group include discussing ways in which it can continue supporting the Department in the coming months, particularly given that many countries, including Canada, are facing second and third waves of the pandemic, and will likely be faced with other global health crises in the future. 13 The Working Group has recently become a more permanent fixture of our Department through the development of terms of reference that will enable it to tackle issues related to wellbeing more broadly. We are currently working on convening a speaker series that can help create opportunities for connectivity and provide Department members with additional strategies for maintaining wellbeing. Although a more concerted effort will be required to address broader stressors such as childcare, we have been encouraged by our membership to invite speakers with expertise in child psychology and wellbeing so as to initiate a conversation on ways of supporting family wellbeing among members of our Department.

There is also the potential for our model to be scaled in order to create a faculty‐wide, institution‐wide, or regional approach to addressing wellbeing. An area of interest has been the establishment of a regional mentorship and support network that could see support expanded beyond the institution. Such an initiative could increase the capacity to provide support and help address issues of confidentiality as participants would be less likely to have existing professional relationships with one another. The Working Group also remains focused on how it can continue to promote EDI through its membership, operations, and collaboration with other groups.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As a quality improvement initiative, this work was deemed exempt from the ethics approval process by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: supporting information

Appendix S2: supporting information

Appendix S3: supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Jillian Lopes for preparing Figure 1 and Lisa Kennedy for providing details about the weekly online drop‐in support group.

Acai A, Gonzalez A, Saperson K, on behalf of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences COVID‐19 Wellness Working Group . An iterative approach to promoting departmental wellbeing during COVID‐19. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28:57-62. 10.1111/jep.13601

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wald HS. Optimizing resilience and wellbeing for healthcare professions trainees and healthcare professionals during public health crises—Practical tips for an ‘integrative resilience’ approach. Med Teach. 2020;42(7):744‐755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID‐19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132‐1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133‐2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sullivan G, Simpson D, Artino AR Jr, Deiorio NM, Yarris LM. Medical education scholarship during a pandemic: time to hit the pause button, or full speed ahead? J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(4):379‐383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qian Y, Fuller S. COVID‐19 and the gender employment gap among parents of young children. Can Public Policy. 2020;46(S2):S89‐S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the emotional well‐being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1136‐1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan‐do‐study‐act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):290‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Redick EL. Applying FOCUS‐PDCA to solve clinical problems. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1999;18(6):30‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (standards for QUality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):986‐992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart‐Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R, Platt S, Parkinson J, Weich S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick‐Edinburgh mental well‐being scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blumer H. What is wrong with social theory. Am Sociol Rev. 1954;19(1):3‐10. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we got to COVID‐19. Cell. 2020;182(5):1077‐1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: supporting information

Appendix S2: supporting information

Appendix S3: supporting information

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.