Abstract

Aims

The overall aim of this evaluation was to look at the impact of the changes in working practices during the pandemic on nurses. This secondary analysis provided an evaluation of virtual care and being able/required to work from home.

Design

This was secondary analysis of an evaluation using semi‐structured interviews.

Methods

Conducted at a single National Health Service (NHS) university hospital in the United Kingdom between May and July 2020. Forty‐eight operational leads and nurses participated in semi‐structured interviews which were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using a framework analysis.

Results

Two overarching themes emerged relating to the patient experience and nursing experience. There were both positive and negative elements associated with virtual care and remote working related to these themes. However, the majority of nurses found that virtual clinics were useful when proper resources were provided, and managerial strategies were put in place to support them. Participants felt that virtual care could benefit many but not all patient groups moving forward, and that flexibility around working from home would be desirable in the future.

Conclusion

Virtual care and remote working were implemented to accommodate the restrictions imposed because of the pandemic. The benefits of these changes to nurses and patients support these being business as usual. However, clear policies are needed to ensure that nurses feel supported when working remotely and there are robust assessments in place to ensure virtual care is provided to patients who have access to the necessary technology.

Impact

This was a study of the move to virtual care and remote working during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Telemedicine and flexible working were not common in the NHS prior to the pandemic but the current evaluation supports the role out of these as standard care with policies in place to ensure that nurses and patients are appropriately supported.

Keywords: COVID‐19, homeworking, nursing, pandemic, patient experience, telemedicine, virtual clinics

1. INTRODUCTION

In the era of the novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) there have been huge changes to everyday life, effectively altering how we currently approach healthcare (Wosik et al., 2020). In the spring of 2020 the Government in the United Kingdom (UK) implemented national and regional lockdowns to minimize the rate of community transmission and protect the National Health Service (NHS) as it attempted to cope with the virus. Due to the pathogenicity and virulence of COVID‐19, face‐to‐face clinical appointments were greatly reduced, and outside of urgent trauma care, significant restrictions were placed on outpatient care to limit hospital footfall, reduce patient to clinician transmission and prevent the spread in the general community (Wosik et al., 2020). To respond to the new demands, virtual care quickly became a necessary surrogate to in‐person care (Bashshur & Shannon, 2020; Murphy et al., 2020). Virtual care reflects a spectrum of interactions between patients and/or members of their healthcare team delivered remotely, wherein the application of information and communication technologies are used to provide elements of healthcare without the need for face‐to‐face contact (Shaw et al., 2018; Speyer et al., 2018).

2. BACKGROUND

Virtual care has been in use throughout the last century, yet full scale adoption into healthcare systems has yet to be achieved (Bashshur & Shannon, 2009). Historically the medical community has been reluctant to fully engage with virtual care, and opinions on its efficacy have been mixed despite the evidence supporting its practicalities and use by a broad range of health professionals (Wosik et al., 2020). Prior to the COVID‐19 outbreak, interest in virtual care was on the rise. In 2018 the World Health Organization (WHO) called on governments to assess the current/potential use of digital technologies in their healthcare systems (WHO, 2018). The NHS responded with a comprehensive digital transformation strategy (NHS England, 2019). However, it was the rapid onset of COVID‐19‐specific restrictions that became the main driver for immediate adoption of virtual care in the UK. Virtual care has the potential to address the on‐going challenge of timely access to health care. For healthcare professionals, virtual care has been shown to provide greater flexibility in their working day, as well as improved autonomy in their provision of patient care (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Hollander & Carr, 2020). For patients, the use of virtual clinics reduces travel costs and has lowered overall admissions to hospitals in certain patient groups, such as the elderly (Lilliecrap et al., 2021). The use of virtual care for some, if not the majority of healthcare appointments, can help provide equitable healthcare to more remote communities (Stokel‐Walker, 2020; Wosick et al., 2020) and contributes to shorter wait lists, which are critical for patients with quickly deteriorating conditions or seeking a timely diagnosis (Murphy et al., 2020). Reducing waiting times consequently allows for higher volumes of patients to be seen by the appropriate professional, thus benefiting the system as a whole (Lilliecrap et al., 2021).

The field of virtual care faces several critical challenges that require attention. Concerns have been raised specific to continuity of care, education and training of healthcare providers, and the potential risk of limited digital health literacy further exacerbating health inequalities (Narasimha et al., 2017). It is argued that virtual care is not suitable for all patients, for example those with complex needs, those who do not have access to or feel comfortable using technology (Narasimha et al., 2017; Wosik et al., 2020). Technological issues, such as poor quality or lagging of video feed can negatively impact the clinician's ability to gauge body language and nonverbal cues and affect their ability to provide adequate consultations (Sinha et al., 2020). Thus, it is critical that virtual care be embedded as a complementary pathway to providing care where appropriate rather than fully replacing face‐to‐face delivery of health services.

Prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic, patients and clinicians were hesitant to engage with virtual care and change well‐established routines (Lilliecrap et al., 2021; Sharma & Clarke, 2014). Yet for those who did engage, satisfaction was high (Azad et al., 2012). During the COVID‐19 pandemic, virtual care offered a way to balance the supply of clinical services during each surge in demand, while also providing healthcare access regardless of physical or geographical boundaries (RGCP, 2020). This further helped protect the available stock of important resources such personal protective equipment and enabled shielding patients to maintain communication with their healthcare team (Hollander & Carr, 2020). Early reports suggested high levels of satisfaction among those who engaged in virtual care in the UK during the pandemic, with 98% reporting a desire to use virtual care again, even after COVID‐19 restrictions were lifted (RGCP, 2020; Sinha et al., 2020).

A secondary element of virtual care highlighted during the pandemic was the ability for healthcare professionals to work remotely. Remote working helps protect staff classed as high risk, such as those who were immunocompromised or caring for vulnerable dependants (Wosik et al., 2020). Working from home presents several challenges and has been met with a level of reservations from a mostly conservative workforce (Giurge & Bohns, 2020; Tawfik et al., 2018). Recent studies indicate that working from home is not only possible but effective, and in many cases, a preference for healthcare professionals if they are given the opportunity (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020; Hoffman et al., 2020). However, negative experiences associated with working from home have also been reported, specifically around lack of separation between work and home life (Giurge & Bohns., 2020), difficulties caring for dependents (e.g. schools being shut resulted in balancing work with childcare), or issues with technology (Hoffman et al., 2020). A study of all professional groups working in the NHS, who were working from home during the pandemic showed that 43.4% felt that their work was undervalued or not acknowledged in comparison to their frontline colleagues, and 48% struggled with feelings of guilt due to being at home during a crisis (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020).

The integration of virtual care into standard practice is well on its way and embodies a new normal for healthcare after the resolution of COVID‐19. In particular, it is believed to be the key to improving communication between healthcare, the patient and their wider systems, which has important implications for their treatment outcomes (Hollander & Carr, 2020). If the benefits of virtual care are to be fully realized in the NHS, a thorough understanding of individuals’ experiences using virtual care during this unique time is needed.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aim

The purpose of this study was to explore nurses’ experiences of utilizing virtual care, alongside remote working to identify what elements could be implemented into a recovery model following the conclusion of the pandemic.

3.2. Design

This was secondary analysis of semi‐structured interview data collected from nurses as part of a wider service evaluation of the changes to delivery of care to accommodate the pandemic, at a single university hospital in the UK.

3.3. Participants

An initial purposive sample of hospital‐wide operational leads were recruited through targeted invitations from a senior nurse, to describe the changes to services across the hospital (n = 17), then a convenience sample of nurses at different levels of seniority were invited to participate through the Trusts group email lists (n = 31). This secondary analysis focused on the experiences of nurse managers (NM; n = 15), clinical nurse specialists (CNS; n = 14) and clinical research nurses (CRN; n = 2).

3.4. Ethical considerations

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the UK Framework for Health and Social Care Research (Health Research Authority (HRA), 2017). The HRA has the Research Ethics Service as one of its core functions and they determined that the evaluation of these data were originally obtained for was exempt from the need to obtain approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/about‐us/committees‐and‐services/res‐and‐recs/. The purpose of the evaluation was explained to participants at the beginning of the video call, who then were given the opportunity to ask questions. If they were happy to continue, they were asked to give a recorded consent. All participants were able to stop the interview at any time and were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. Interviews were transcribed and anonymized. Voice recordings were deleted, and the anonymized transcripts were stored on a password protected NHS computer system. Approval for secondary analysis was provided by the hospital head of research governance.

3.5. Data collection

Data were collected through individual semi‐structured interviews between May and July 2020. The guide for the interviews with operational leads included a description of the changes in service delivery the participant led and their perception of what worked well and what were the challenges. The analysis of these data informed the structure of the interviews with nurses, reflecting on their experiences of the service changes and what they felt worked well or could be improved (Appendix). Interviews were conducted through video conference software and were digitally transcribed. Interviews were performed by three researchers (RMT, LH, AP) with experience of interviewing participants. Participants were separated by banding and divided among interviewers to align with their level of seniority in the hospital. Interviews were between 40 and 60 min long.

3.6. Data analysis

Digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Framework Analysis (Richie & Spence, 1994). The Framework for the evaluation was developed from the interviews with operational leads. This included 10 main themes, each containing three to eight subthemes (Appendix). Virtual care experiences and experiences of working from home emerged as core elements crossing all 10 themes and therefore a secondary framework was developed to focus specifically on virtual care and working from home, to further illuminate the experience. Transcripts were re‐reviewed and additional indexing was applied from the new framework. The main framework was developed by two members of the evaluation team, checked by an independent researcher with expertise in qualitative research; the secondary framework was reviewed by a third member of the evaluation team.

3.7. Rigour

The criteria proposed by Beck (1993) were used to establish methodological rigour. Credibility was established by using a semi‐structured guide for the interviews (Appendix) but also empowering participants to expand on their responses according to their personal experiences. To ensure the fittingness of the findings, the secondary analysis included a purposive sample of nurses whose practice was impacted by the pandemic to require remote working and the move to virtual clinics. To ensure the auditability of the findings, framework analysis was used, which enabled multiple researchers to review the coding to check for accuracy of the interpretation.

4. FINDINGS

There were two overarching themes emerging from interviews: the perceived barring virtual care had on patient experience from a nursing perspective; and nurses’ experiences of virtual care and remote working. It was found that for most themes there existed a duality of positives and negatives.

4.1. Potential barring on patient experience

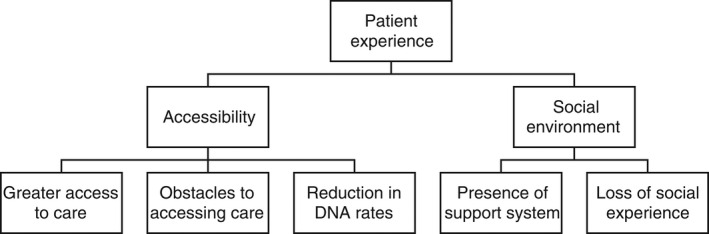

This theme is based on nurses’ perceptions of how virtual care impacted their patients, which comprised of multiple subthemes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Major themes and subthemes for the potential barring on patient experience. DNA, did not attend

4.1.1. Accessibility

Greater access to care

Participants identified areas in which they perceived that the use of virtual care had positive impacts on patient's experiences. In particular, the majority believed that virtual care facilitated greater access to medical care for their patients, while also eliminating various barriers such as travel, finance and having to balance appointments with work schedules. By offering virtual appointments to patients, it allowed for them to attend remotely which was perceived as a benefit for many who would have to make long commutes into the hospital and eradicated their need to take time off of work to attend these appointments.

Some of our patients live quite some distance away with, you know, they might have mobility issues or lots of other comorbidities that make getting to hospital difficult and expensive, of course. So I think I like the idea that we can offer them more choice at the moment. (CNS_P001)

This also eliminated the process of having to return home after making a journey to the hospital, which could be difficult if the appointment involved bad news. This was particularly salient during the pandemic as heavy restrictions on visitor policies meant that many would have had to attend clinics alone. Allowing patients to remain at home with family and access their clinics virtually therefore negated this potentially distressing circumstance.

I think also a lot of patients have preferred not to come in, not doing face to face clinics, a lot of patients, you know, have found telephone clinics very helpful. You know, they've been protected, they’re home. (CNS_P017)

Obstacles to accessing care

Despite the benefits of virtual care, nurses also perceived some negative impacts for their patients. One of the main difficulties was the lack of accessibility of technology for some patients, such as the elderly. Furthermore, for those who had access to technology, they did not necessarily have the capability to use it with confidence, and if they did not have support systems at home to help, this was a potential obstacle for patients to use it. Some nurses noted that there were certain subgroups of patients who were unable to engage at all with virtual appointments during the pandemic and feared that they were at risk of becoming neglected by these advances in technology. Similarly, technological issues inherent to these platforms could frustrate or further aggravate a patient's reluctance to engage. Simple things such as the quality of the video could affect the flow and efficacy of the intervention.

I do know that a lot of people, you know, a lot of patients may not have that capability. The other thing about that is…if there's any technical problems, it can delay things hugely. (CNS_P007)

Reduction in DNA rates

Nursing staff felt that virtual care had clear benefits for protecting vulnerable patients from making unnecessary journeys during the pandemic, and as a result of this, the ‘did not attend’ (DNA) rates were noted to be lower than normal, as patients were able to attend easily without making too much compromise in their day‐to‐day lives. The convenience of not having to attend the hospital also had a financial benefit, as many patients were receiving specialist care so the hospital was not local. The use of virtual care appeared to create a positive feedback cycle in which remote access to their healthcare workers helped to facilitate their care, without much personal or financial cost to themselves.

DNA rates…have been very, very low, you know, typically runs around 14% or so. I think probably it's 5% if that, you know, because people are home usually, and seem to appreciate the call. (CNS_P022)

Staff noted that due to the decrease in DNA rates they were able to see a much higher volume of patients than they would see in face‐to‐face clinics. Nurses felt this made them more productive and removed the necessity for rescheduling patients and delaying elements of their treatment. They also noted that the ability to remotely access patients negated the Trust's need to organize costly travel for those who could not travel by conventional means, which was a further financial and time benefit for the NHS.

Hospital transport, that must be costing the NHS a fortune, I'd be more inclined to say to them now, let’s not go with the hospital transport and everything. Let's do it by telephone. (CRN_P020)

4.1.2. Social environment

Presence of support system

Another benefit highlighted by nurses was that it gave patients the opportunity to have more of their support systems present during their appointments. Prior to use of virtual clinics it could be logistically difficult for patients and their families to attend clinics together. This resulted in some patients attending clinics alone, lacking their support structures and having their family feel excluded in terms of medical developments. Likewise, families may struggle to attend appointments while balancing other life responsibilities. With the option of virtual clinics, patients and their family members could be more easily present, meaning the patient had the added benefit of being in comfortable surroundings with their support structures. Family members could be present to engage with nurses who could address any questions or concerns they had. In doing so this mutually strengthened the relationships between the patient, their support systems and the medical team.

Their partner or family member can join in on the conversation. And certainly from speaking to my colleagues, we've all felt that and doing telephone clinics is a way forward. (CNS_P017)

However, others felt that this may not suit everyone, and that there were patients whom they felt benefited from attending face‐to‐face clinics. This included patients where there were safeguarding concerns, or those who did not wish to have family involved in their care, and therefore finding space and privacy for virtual appointments was more difficult.

Loss of social experience

The inverse of the removal of travelling for appointments, seen by many as a positive outcome, for some patients this was one of their main social outlets. Vulnerable patients or those with complex needs may not get to engage socially as easily as others, particularly during times of social distancing or shielding. Some staff worried that this may isolate those patients further and could have potentially negative effects on their well‐being. Likewise, for some patients where hospital visits were regular parts of their routine, the relationships they built with staff could be minimized by moving towards more virtual based care. Interestingly, this ran parallel to experiences of staff who were working at home remotely, realizing how isolating it can be, and missing the everyday social connections with their co‐workers.

…sometimes it's the only way that they get to leave where they live. That's depriving them of that. (CNS_P008)

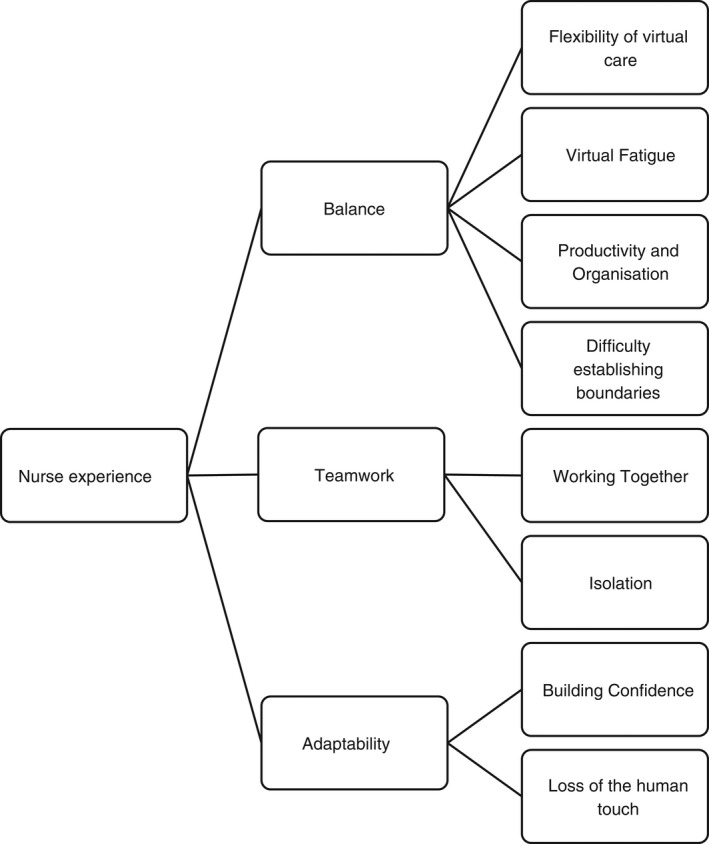

4.2. Nurse's experiences of virtual care and remote working

This theme relates to using virtual care and remote working in the nursing role, and the ways in which it both positively and negatively affected nurses’ experiences. The subthemes are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Major themes and subthemes for nurse's experiences of virtual care and remote working

4.2.1. Balance

Flexibility of virtual care

The majority of nurses felt that virtual care was beneficial for their patients, and in turn beneficial for themselves. A key benefit of using virtual care for outpatient clinics was that they were more likely to run to time, which historically was difficult to achieve in everyday practise. Logistical issues, such as patients being late to clinic due to transport problems were negated. Long waiting times were greatly reduced, and with patients being able to wait for clinics in the comfort of their own homes this was perceived to be much less arduous then spending long amounts of time in hospital waiting rooms. Removing these unavoidable frustrations from clinic days allowed for greater flexibility for both staff and their patients and helped improve rapport and experience for both groups.

One of the issues that we've always had is that our clinics never run to time. And what happens then, is that you get patients who eventually come in for their clinic, they're very distressed, they can be very angry. So before you can even start talking about what they're there to discuss, you have to kind of break down some of those barriers by trying to calm them down, you know, lots of apologies, that sort of thing. So the fact that these people aren't actually making their way to the hospital spending, you know, extended waits in the [location] waiting for their appointment, the fact that they can do that at home and just be getting on with their daily lives. I think for everybody's stress levels, doctors and patients and nurses and clinic staff, who were all patient facing, I think it makes it a lot less stressful for everybody. (CNS_P006)

Virtual fatigue

Fatigue from attending large numbers of online clinics or meetings was noted, which participants felt required a different level of cognition to pay attention to, compared with face‐to‐face interactions, as they lacked much of the stimulation of in‐person presence. Some felt there was a certain level of coldness associated with attending meetings online, particularly if those present did not turn on their cameras. This further reflects staff feeling isolated or cut off from their co‐workers.

I think meetings virtual meetings are much more productive, although I have to say they are exhausting. And I did six the other day. And I was absolutely exhausted because it's all about concentration, isn't it and listening, whereas if you're in a meeting with a roomful of people, you can probably drift off a little bit or look at your emails or you know, you don't have to so much concentrate on the conversation. Whereas if you're doing a virtual meeting, you have to listen. Always, all the way through the meeting to capture what's being said done, decided, etc. (CNS_P017)

Productivity and organization

Having the option to work remotely was noted by many nurses as having a positive impact on their work. They perceived it to be associated with higher levels of productivity and organization. Nurses felt that working in the home environment allowed them to get much more of their paperwork completed than they would in the hospital setting, where they were often distracted.

It has been proven that it was effective. And we managed to cover every single aspects of our job without compromising any single one. And it’s nice; we have a great routine, great organization, etc, etc. So that's the positive side of COVID that I can see…I find myself much more organized. (CNS_P008)

Having the ability to set aside time to get these tasks done without distractions also equated with reduced feelings of stress. Remote working provided a comfortable and quiet environment free from the stressors of onsite work, allowing nurses to engage with tasks they often found difficult to apportion appropriate time to for.

And I think because my mind is much clearer when I'm at home, there's no distraction. So I get things done very quickly… and very effectively. (CRN_P003)

Furthermore, organizational annoyances such as hot desking were essentially eradicated. In normal circumstances, desk space in the hospital was often an area of contention for nurses who were expected to do certain amounts of desk work. This was heightened during times of social distancing. Allowing nurses the option to work from home, for even some of the week, gave them the ability to process these tasks efficiently and therefore allowing them to engage more with clinical work when onsite.

I can plan my day in a much better way …like we were fighting for computers in the office. There was no space for all of us to be, how many times I arrived in the office and I had to go back to the command centre because there was no desk…we were all hot desking (CNS_P005)

Difficulties establishing boundaries

In terms or remote working, while many did find it greatly increased their productivity some felt it actually increased the level of pressure in their role. Some displayed levels of guilt at not being onsite during a crisis and made personal compromises such as a working extra hours or working the time they would have spent commuting– feeling they owed this to their colleagues. Others noted that when working from home they felt increased pressure from onsite colleagues to be able to complete tasks for them quickly, and that there was a perception and expectation that those working from home had more time to get these tasks done rapidly.

I've never spent so much time on the laptop, at home, and even at times, I would go overtime. After five…I can still find myself working, you know, and because they gave me a lot of worksheets to do, like different studies and have to create all of those, and I was really busy. (CRN_P003)

The boundary between work and home life was sometimes difficult to establish. Some nurses noted that when they were working from home indefinitely it could lead to feelings of lower motivation. Lacking the normal everyday experiences of commuting to work, encountering colleagues and meeting patient face‐to‐face meant staff were less stimulated throughout the day. Some felt this lent itself to feelings of loneliness, lethargy and boredom, and that working from home meant the aspects of their life in which they used to relax or enjoy became synonymous with their working days.

What's been at times difficult psychologically is just not getting out the house and not having that kind of clear, clear‐ish division between what's work and what's home. So, you know, I, I come up with stairs, I'm in a spare room/study, and that's my commute to work. And when I’m finished work, straight out of, you know, doing patient stuff…I'm down in the kitchen with the rest of the family. And so, I guess in some ways…strangely, I miss the commute, because it gave me that period of that time and space between work and home. (CNS_P022)

4.2.2. Teamwork

Working together

Another positive aspect of using remote access for staff included the use of virtual platforms for multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs). Many nurses noted the benefits of being able to attend meetings virtually, which allowed for greater flexibility in their working day. MDTs were more likely to be attended by a wider selection of staff involved in patient care, which facilitated the perspectives of different disciplines to be voiced and interactions with one another on a more frequent basis. This helped nurses form a holistic perspective of patient care and was believed to benefit their approaches to treatment. Furthermore, it encouraged more interaction between disciplines which may not have had a chance to meet in person previously often due to conflicting schedules.

I think having more different disciplines working together closely, looking after patients works really, really well. So I think that would be great to take that forward and having staff who don't normally work on the front line or are more in the back sort of clinics or, or in labs, having them come out, and sharing their knowledge with us was really useful. And having them review patients with us as well, bringing their expert knowledge in was really helpful. (CNS_P011)

Isolation

Despite the increase of interdisciplinary communication, nurses who were mostly working remotely voiced feeling isolated from their own teams and missed having the contact they would normally have with their colleagues in person. There was a sense of isolation and loneliness, which some described as feeling not only disconnected from their role and the work with their patients, but also feeling disconnected from the social relationships they had built with their co‐workers. In particular those who were required to shield during the first wave found this experience very psychologically isolating and lonely.

Working from home, you don't have any anyone to talk to that much…and there's because we're not face to face, you know, the human interaction is a bit lost… So there's nobody really to talk to and nowhere to go but the house…the only thing I really miss is the interaction human interaction with my colleagues. (CRN_P003)

4.2.3. Adaptability

Building confidence

Some nurses described reluctance from their colleagues or even themselves to use these new platforms. Many felt this reluctance was eventually overcome when they developed confidence, especially with support from IT (information technology), which was noted to be important. Initially, participants felt that they had always been told that working in this manner would be impractical, which made the experience quite daunting.

Streamlining clinics made it evident they were doing things for years that didn't need to be done; the resistance from doctors previously to do telephone clinics is now over because they have no choice but to do it. (NM_P029)

When it came time to rapidly implement virtual care policies, many found it surprising how easily they could work remotely when given the right resources and support. While there were initial adjustments to be made, the majority did feel confident in their use of virtual platforms. However, it was still felt that further training for professionals on the use of virtual care was needed.

Being able to implement virtual clinics was possible because the IT team attitude went from 'No we can't do that' to implementing everything you needed to make it happen. (NM_P026)

It was also noted that using aspects of remote access allowed them easier access to attend training, which could often be difficult to arrange if it involve nurses leaving the clinical areas—despite the clear benefit of staff participating in new and available training. Use of these technologies could therefore be used to help to solve certain logistical paradoxes often experienced by healthcare staff.

I think that's it’s the not having to go places to train and to have meetings. I think that's, for me, a really good thing. (CNS_P015)

Losing the human touch

The most voiced criticism of using virtual technologies in the nursing role was not being able to see patients in person. Some found it difficult to assess patients thoroughly through virtual care, and that if there was no video link then it could be quite impersonal and hard to build rapport with a patient. Lacking visual cues to how patients were feeling was difficult for some nurses who felt they often relied on these to gain a better understanding of their patient's needs.

You can't really pick up nonverbal cues from people in the same way…that’s harder because you're not firing on all cylinders with your ears and your eyes and watching body language and things. You're just listening to a voice. (CNS_P008)

Similarly, they felt it was still important to be able to see some patients face‐to‐face if there were safeguarding issues or mental health problems, as they needed to be able to check in person to more effectively gauge how they were. Participants were also concerned that patients may not be able to disclose their circumstances if they were home with family present.

I know that when we think about safeguarding with our patients, there's quite a few that we do want to clock eyes on and make sure that we see them or bring them in. But I guess that could be decided on a patient to patient basis. (CNS_P007)

Nurses who were apprehensive using technology, and who often relied on face‐to‐face assessments and the personal touch when dealing with clients, there was a disconnect described in their interactions with their patients. Lacking the visual clues meant that they had to rely more on what patients were telling them, though a positive of this may have been encouraging the patient to use their voice and empowered them to engage more in their care. This perceived distance and disconnect could be aggravated further due to technological issues, such as feeds lagging, freezing or the picture not being clear enough. This highlighted that while some found virtual care more accessible after building their confidence with the technologies, there were still some nurses who felt ill equipped and disconnected from their work.

There's a lot of things with checking out without them knowing it just by looking at them, how they move around the clinic room, how they carry themselves their mood, you can't pick that up on a telephone clinic. So I'm probably missing some quite important things that I wouldn't normally miss. (CNS_P020)

5. DISCUSSION

Our evaluation explored the experiences of nurses utilizing virtual care and remote working during the pandemic in a single hospital, with the aim of identifying elements that could be adopted as common practice. We found that there were several positive and negative aspects associated with virtual care, which lends further credence to past findings that posit virtual care as a system which benefits some but not all. Nurses believed that virtual care impacted the experience of their patients. It was felt that provision of virtual care greatly improved the accessibility of healthcare for some, which also helped to lower the rate of missed appointments and allowed support systems to be more involved in joining in the conversations with the medical team. However, the inverse of this was also voiced, with virtual care potentially posing obstacles for accessing healthcare due to lacking adequate resources, confidence, skill or support. Nurses worried that moving towards virtual care would alienate some patients who enjoyed the social routine of attending hospital appointments and interacting with staff on a regular basis.

In terms of the impact on the nurse's own roles, reactions were somewhat mixed. Some enjoyed the flexibility of remote working while others found that working from home could lead to virtual fatigue. Some nurses felt that remote working increased their productivity and organization, while others struggled to establish boundaries between work and home life, leading to feeling overburdened and stressed. The use of virtual care was seen to improve the level of interdisciplinary working, but inversely could lead to isolation from one's own team as a consequence. Attitudes towards virtual care and remote working were somewhat ambivalent to begin with, and some felt resistance from their co‐workers to fully engage; however, through exposure many found they gained confidence. A grievance that all nurses expressed to some degree was the loss of the human connection when not working face‐to‐face with patients. While some managed to positively adapt, others found that they could not adapt their ways of normally assessing patients for virtual care. The somewhat dyadic findings of this evaluation are in line with previous research on virtual care, which state that it is a system which works very well for some people but not for everyone, which is vital to keep in mind when considering its future applications (Bashshur & Shannon, 2009; Hollander & Carr, 2020; Stokel‐Walker, 2020).

As seen in the literature, virtual care is accredited with greatly improving access to care across various populations (Lilliecrap et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2020). Nurses believed that adopting virtual care during the pandemic was fundamental in maintaining services. It was felt that beyond the pandemic that use of virtual care could enable healthcare to be more equitable, and reach further communities, which has also been shown previously (Wosick et al., 2020). Virtual care has been noted to be acceptable to the general public (Azad et al., 2012; Sinha et al., 2020) and patients were happy that they could still be connected with their healthcare team (RGCP, 2020). This evaluation mirrored these findings, believing that virtual care significantly improved access of care. The lower DNA rates and decrease in the amount of missed appointments positively contributed to shorter waiting lists. This is critical for patients with quickly deteriorating conditions, or those seeking a timely diagnosis (Murphy et al., 2020). Reduced levels of missed appointments allowed for higher volumes of patients to be seen by the appropriate professional, thus benefiting the system as a whole (Lilliecrap et al., 2021).

Despite this, there were fears of alienating subsections of the population and a sense that certain patients were at a higher risk of falling through the gaps. For some it was the use of virtual technology itself which was likely to be an obstacle for engaging. Patient's reluctance or hesitancy to try new technologies has been previously linked to lower success for virtual care (Lilliecrap et al., 2021). While for some it was just a case of practise to help build their virtual literacy skills, there were others who simply could not engage throughout the pandemic which was cause for concern. Populations such as the elderly or those with autism are more likely to encounter obstacles when using virtual care which may act as a deterrent (Narasimha et al., 2017; Wosik et al., 2020). Identifying those most at risk of becoming lost in a system of care is necessary to ensure that these patients continue to have access and engage with their treatment plans.

Increasing the accessibility of virtual care could have a polarizing effect on patient's social support and environment. Allowing patients to access clinics in the comfort of their own home has the advantage of creating safe and comfortable surroundings to maintain calm (Bashshur & Shannon, 2009) while also increasing the likelihood of having their family present. Historically, communication between healthcare staff and family is a source of contention (Newell & Jordan, 2015). Patients may not always take in all the information they are given in clinics and allowing family to be present to engage in real time with nurses has shown to improve the retention of information and benefit patient and family anxieties (Newell & Jordan, 2015). Families frequently experience periods of liminality and powerlessness in the wake of illness; this could be addressed by increasing collaboration between them and the healthcare team through virtual clinics (Clay & Parsh, 2016).

However, the inverse of this is also true; some patients may have a more complex home life or have surroundings in which they do not feel safe or comfortable to discuss their experiences. Some patients may be subject to safeguarding concerns and need to interact with nursing staff away from potentially harmful elements of their home life. Those who have children may also struggle to engage virtually if they have concerns over discussing illness around them (Bashshur & Shannon, 2009). Similarly, interacting with healthcare professionals and discussing sensitive topics may be more difficult for people if they have family or loved ones in their environment, who they do not wish to hear their discussions (McCord et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2015).

Remote working enabled nurses to have flexibility in the way they worked; however, some expressed difficulty with creating a proper work life balance, which has been found previously in other studies of remote working (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020, Giurge & Bohns, 2020). Those who work remotely are still entitled to routine breaks and working only in their agreed hours but some felt that managers and co‐workers increased pressure to work harder or faster merely because they were working remotely. This has been shown previously and should be considered a target of work culture to be dismantled moving forward (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020). A concern of remote working is that it may contribute to burnout, caused by this lack of balance, particularly in people's failure to separate work and home life (Giurge & Bohns, 2020). Pandemics greatly increase the likelihood of staff burnout in general, and well‐being must be closely monitored to avoid a service wide burnout following its resolution (Hoffmann et al., 2020). The majority of participants reported enjoying the experience of working from home as it reduced time commuting and allowed them to spend more meaningful time with family. The ability to work remotely has shown to act as a protective factor mitigating provider burnout (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2020). It would therefore be reasonable to suggest that remote working is at its most effective when it is optional rather than mandatory and having the freedom to choose onsite or remote working, or a mixture of both, is most likely to have protective potential. Given the threat of burnout to healthcare workers during a pandemic, finding avenues to strengthen their practises is critical (Hoffmann et al., 2020).

Virtual care seemed to bolster interdisciplinary teamwork while at the same time alienating individual team connections. Moving MDT clinics to a virtual format made them overall more accessible to a wider range of staff, and nurses benefited from having the perspectives of many different disciplines on patient care. Many felt this was a positive step towards the more holistic model that healthcare has been moving more towards (Stokel‐Walker, 2020). However, nurses who were working remotely felt isolated from their team, particularly when it was mandatory due to shielding. Teamwork is a fundamental cornerstone of the nursing profession and a protective factor against poor mental health and experiences of burnout (Sharma & Clarke, 2014).

When nurses were removed from their teams completely, they were shown to experience more negative emotions than those who had the option of working remotely occasionally throughout the week. Some felt a perception from their colleagues that those working remotely had it easy, and experienced guilt at not being part of the frontline defence of the virus. This is similar to other studies done during the COVID‐19 pandemic, which have shown that staff relegated to home working ran the risk of feeling isolated and under appreciated by their team, despite the work they still contributed (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020). When virtual team meetings were held more frequently it improved team morale, allowed for the maintenance of previous relationships, encouraged further bonding and allowed remote staff to still feel part of the team. It was also found that these meetings had the potential to incorporate some elements of socializing which could further improve mood for both onsite staff and remote staff alike.

5.1. Limitations

The current evaluation has several limitations. First, this was secondary analysis of a wider evaluation; therefore virtual care and remote working were not the sole focus of the interviews. Interviews specific in this area may have included additional probing questions on the barriers and challenges specific to this. Despite this, these themes emerged organically during the interviews, and were explored by the interviewer due its apparent impact on nurse's experiences during COVID‐19. The wide scale and in‐depth discussion of these themes warranted the authoring of this paper, rather than it being a subtheme in a larger evaluation. Second, this was a single centre evaluation and reflected the practices and decisions made in this one organization. However, as a large inner city university hospital, the results may resonate with other organizations. Third, only nursing staff were interviewed, so it does not reflect other professional groups who were using virtual care, for example, medics and allied health professionals, or a large number of administrative and clerical staff who were required to work from home. It is important that their experience and perceptions are elicited to inform any future policy/guidance. Finally, and most importantly, while we present patient experience, this is through the perception of nurses. To fully capture the experience of those utilizing healthcare during the pandemic it would be necessary to engage patients on how they found the experience of interacting with their treatment through virtual care. Despite these limitations, we were able to evaluate changes to service delivery in real time so we have an accurate recollection of nurse's experiences of using virtual care and working from home. It also included nurses in a range of roles so presents multiple perspectives.

6. CONCLUSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is still a dominant feature in the landscape of healthcare and is likely to be so for some time to come. To continue to provide optimal and consistent care to patients, while protecting them, their families and our healthcare workers, use of virtual care is an imperative step forward. However, moving towards business as usual it is clear that virtual remote access has added benefit for being integrated into the way we continue to engage our patients. It is likely there will be many epistemic changes post‐pandemic, and a return to the way in which we once worked is highly unlikely. To embrace what is sure to become the new normal, becoming versed in the use of virtual care seems both progressive and highly pragmatic. Historical reservations around working remotely have been clearly disproven, with a wide varieties of jobs being shown to be possible offsite and approaching this with a level flexibility is key to not only maximizing the way our staff are working during times of social distancing, but beyond this as well. The simultaneous increase in productivity and decrease in perceptions of stress, combined with the readily available forms of technology show that it is capable to not only move forward in how we deliver healthcare, but ultimately to expand in ways which only some years ago would have seemed impractical. Lessons learnt during the pandemic should not be merely restricted to emergency protocols but become long‐term fixtures in how we think about the delivery of healthcare in the future.

6.1. Implications for nursing practice

The use of digital technology is central to the NHS long‐term plan in the UK (NHS England, 2019) and COVID‐19 has highlighted the needed for an integrative approach to nursing practice as we know it. Results from this evaluation emphasized several benefits of virtual care for nurses and patients, which should be considered when integrating virtual care into post‐pandemic nursing practice. In addition, limitations or concerns around virtual care require attention and further investigation. Most notably, the need for a typology to facilitate decision making around appropriateness of virtual care versus face‐to‐face consultation for individual patients and situations. Training programs are also needed to support nurses in how best to delivery virtual care and stay connected with their patients. Identifying patients who are likely to fall through the gaps of virtual care alongside staff who are unconfident or have trouble adapting to new manners of working would need extra support to build their virtual literacy will be very important (Sharma & Clarke, 2014). Akin to past findings, virtual care is as much a ‘some but not all’ experience for staff as much as it is for patients.

After the first wave of the pandemic the NHS launched We are the NHS: People plan for 2020/21 (NHS England, 2020), which outlined what people working in the NHS could expect to “foster a culture of inclusion and belonging” (NHS England, 2020, p. 3). The report outlined the strategy for caring for staff working in the NHS and one of the central recommendations for retaining staff was flexible working. Flexible working can be more easily accommodated in administration, Monday to Friday and non‐clinical roles but can be more challenging for nurses who are working shifts and deliver patient care. When local policies are being developed for flexible working, this needs to be considered and flexible options offered, such as self‐rostering. In addition, pilot training programs have been rolled out aimed at improving skills specific to delivering virtual care. Further research on how patients experienced virtual care will be necessary to ensure that the provision of their care remains as patient centres as possible.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict no interest declared by the authors of this paper.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15050.

Supporting information

Appendix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Nursing and Midwifery Leadership Team for commissioning and supporting the evaluation these data were derived from. We also thank all the participants for giving us their time during the pandemic and for sharing so honestly about the impact of working in a pandemic.

Hughes, L. , Petrella, A. , Phillips, N. , & Taylor, R. M. (2022). Virtual care and the impact of COVID‐19 on nursing: A single centre evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 498–509. 10.1111/jan.15050

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors. The CNMAR is funded through UCLH Charity, Rachel Taylor is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Nurse Research Leader. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of UCLH Charity, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not available.

REFERENCES

- Azad, N. , Amos, S. , Milne, K. , & Power, B. (2012). Telemedicine in a rural memory disorder clinic—Remote Management of Patients with dementia. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 15, 96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashshur, R. , & Shannon, G. W. (2009). History of telemedicine: Evolution, context, and transmission (Vol. 2). MaryAnn Liebert. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. T. (1993). Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 15, 263–266. 10.1177/019394599301500212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, I. , Davies, G. , & Adhiyaman, V. (2020). The contributions of NHS healthcare workers who are shielding or working from home during COVID‐19. Future Healthcare Journal, 7(3), e57–e59. 10.7861/fhj.2020-0096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay, A. , & Parsh, B. (2016). Patient‐ and family‐centered care: It's not just for pediatrics anymore. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(1), 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurge, L. M. , & Bohns, V. K. (2020). 3 tips to avoid WFH burnout. Harvard Business Review. April 3. [Google Scholar]

- Health Research Authority . (2021). Is my study research? Retrieved March 8, 2021, from http://www.hra‐decisiontools.org.uk/research/ [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K. E. , Garner, D. , Koong, A. C. , & Woodward, W. A. (2020). Understanding the intersection of working from home and burnout to optimize post‐COVID19 work arrangements in radiation oncology. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 108(2), 370–373. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, J. E. , & Carr, B. G. (2020). Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(18), 1679–1681. 10.1056/NEJMp2003539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilliecrap, L. , Hunter, C. , & Goldswain, P. (2021). Improving geriatric care and reducing hospitalisations in regional and remote areas: The benefits of virtual care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 27(7), 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord, C. , Bernhard, P. , Walsh, M. , Rosner, C. , & Console, K. (2020). A consolidated model for telepsychology practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76, 1060–1082. 10.1002/jclp.22954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. P. , Dennehy, K. A. , Costello, M. M. , Murphy, E. P. , Judge, C. S. , O'Donnell, M. J. , & Canavan, M. D. (2020). Virtual geriatric clinics and the COVID‐19 catalyst: A rapid review. Age and Ageing, 49(6), 907–914. 10.1093/ageing/afaa191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimha, S. , Madathil, K. C. , Agnisarman, S. , Rogers, H. , Welch, B. , Ashok, A. , Nair, A. , & McElligott, J. . (2017). Designing telemedicine Systems for Geriatric Patients: A review of the usability studies. Telemedicine and e‐Health, 23, 459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell, S. , & Jordan, Z. (2015). The patient experience of patient‐centered communication with nurses in the hospital setting: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 13(1), 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS England . (2019). The NHS long term plan. NHS. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online‐version/chapter‐1‐a‐new‐service‐model‐for‐the‐21st‐century/4‐digitally‐enabled‐primary‐and‐outpatient‐care‐will‐go‐mainstream‐across‐the‐nhs/ [Google Scholar]

- NHS England . (2020) WE ARE THE NHS: People Plan for 2020/21—Action for us all. NHS. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp‐content/uploads/2020/07/We‐Are‐The‐NHS‐Action‐For‐All‐Of‐Us‐FINAL‐March‐21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, L. , Reid, C. , & Dziurawiec, S. (2015). “Going the Extra Mile”: Satisfaction and alliance findings from an evaluation of videoconferencing telepsychology in rural Western Australia. Australian Psychologist, 50(4), 252–258. 10.1111/ap.12126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. , & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman A., & Burgess R. G. (Eds.), Analyzing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of General Practitioners . (2020). RCGP survey provides snapshot of how GP care is accessed in latest stages of pandemic. Retrieved July 30, 2020, from https://www.rcgp.org.uk/about‐us/news/2020/july/rcgp‐survey‐provides‐snapshot‐of‐how‐gp‐care‐is‐accessed‐in‐latest‐stages‐of‐pandemic.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Shah, E. D. , Amann, S. T. , & Karlitz, J. J. (2020). The time is now: A guide to sustainable telemedicine during COVID‐19 and beyond. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(9), 1371–1375. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U. , & Clarke, M. (2014). Nurses’ and community support workers’ experience of virtual care: A longitudinal case study. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 164. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, V. , Malik, M. , Nugent, N. , Drake, P. , & Cavale, N. . (2020). The role of virtual clinics in plastic surgery during COVID‐19 lockdown. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 45, 1–7. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s00266-020-01932-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speyer, R. , Denman, D. , Wilkes‐Gillan, S. , Chen, Y. W. , Bogaardt, H. , Kim, J. H. , Heckathorn, D. E. , & Cordier, R. (2018). Effects of virtual care by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 50(3), 225–235. 10.2340/16501977-2297. PMID: 29257195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokel‐Walker, C. (2020). Why telemedicine is here to stay. BMJ, 371, m3603. 10.1136/bmj.m3603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, D. S. , Profit, J. , Morgenthaler, T. I. , Satele, D. V. , Sinsky, C. A. , Dyrbye, L. N. , Tutty, M. A. , West, C. P. , & Shanafelt, T. D. (2018). Physician burnout, well‐being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93, 1571–1580. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2018). Digital health [draft resolution]. A71/A/CONF./1. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_fles/WHA71/A71_ACONF1‐en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wosik, J. , Fudim, M. , Cameron, B. , Gellad, Z. F. , Cho, A. , Phinney, D. , Curtis, S. , Roman, M. , Poon, E. G. , Ferranti, J. , Katz, J. N. , & Tcheng, J. (2020). Virtual care transformation: COVID‐19 and the rise of virtual care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(6), 957–962. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not available.