Abstract

A new nonheme iron(II) complex, FeII(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O) (1), is reported. Reaction of 1 with NO(g) gives a stable mononitrosyl complex Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O) (2), which was characterized by Mössbauer (δ = 0.52 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 0.80 mm s−1), EPR (S = 3/2), resonance Raman (RR) and Fe K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopies. The data show that 2 is an {FeNO}7 complex with an S = 3/2 spin ground state. The RR spectrum (λexc = 458 nm) of 2 combined with isotopic labeling (15N, 18O) reveals ν(N-O) = 1680 cm−1, which is highly activated, and is a nearly identical match to that seen for the reactive mononitrosyl intermediate in the nonheme iron enzyme FDPnor (ν(NO) = 1681 cm−1). Complex 2 reacts rapidly with H2O in THF to produce the N-N coupled product N2O, providing the first example of a mononuclear nonheme iron complex that is capable of converting NO to N2O in the absence of an exogenous reductant.

Keywords: iron, nitric oxide, nitrous oxide, nonheme, reduction

Graphical Abstract

We demonstrate the first example of a nonheme, mononuclear {FeNO}7 complex that mediates the conversion of NO to N2O in the absence of an external reductant. A new mononuclear, 5-coordinate FeII complex is synthesized, which binds nitric oxide to form the {FeNO}7 complex. This complex exhibits a highly activated NO ligand as seen by RR spectroscopy, and generates N2O in THF upon addition of H2O.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is produced in mammals in nanomolar concentrations, and participates in a number of critical biological processes, from cell signaling to blood pressure regulation. During pathogenic invasion, the physiological concentration of NO in mammals increases to micromolar levels as part of the immune response. Microbes such as cyanobacteria, archaea and protozoa express enzymes to combat this influx of NO, including a diiron protein that contains a flavin mononucleotide cofactor (FMNH2), and reduces NO to N2O. The overall reaction catalyzed by flavodiiron protein NO reductase (FDPnor) is given in eq 1. [1]

| (1) |

FDPnor contains a nonheme diiron active site with two five-coordinate Fe centers bound to the protein through 2 N(His)/1 O(Asp or Glu) donor ligands, and bridged by carboxylate and water/hydroxo ligands (Figure 1). The sixth coordination site on each Fe remains open for binding of NO, and is surrounded by non-coordinating water molecules.[2] The balanced reaction in eq 1 shows that two reducing equivalents are required for conversion of NO to N2O,[3] but the timing and mechanism of the reducing events during the catalytic reduction of NO by FDPnor remain poorly understood. The enzymatic reaction begins with the initial binding of NO to the diferrous (Fe2II) state, and spectroscopic evidence shows the successive formation of mononitrosyl {FeNO}7 (Enemark-Feltham notation)[4] [FeII{FeNO}7] and dinitrosyl [{FeNO}7]2 species.[5] An important question is whether the reducing electrons provided by the flavin cofactor are transferred to the diiron active site before or after the critical N–N bond formation step. These mechanistic possibilities are outlined in Figure 1. Mechanism A involves reduction of the dinitrosyl [{FeNO}7]2 site, by either one or two electrons, to give {FeNO}8 species prior to N–N coupling, while mechanism B involves N–N bond formation at the {FeNO}7 stage, followed by the transfer of the reducing equivalents to the final diferric state to regenerate the FeII2 active state. In the latter mechanism, N–N bond formation may occur via coupling of two {FeNO}7 units, or possibly by direct attack of free NO on a single {FeNO}7 site. Evidence for mechanism B was obtained from examination of a deflavinated form of FDPnor, which showed that the {FeNO}7 species was competent to produce N2O in a single turnover reaction.[5a, 6] However, the mechanism could be significantly different under catalytic conditions in the presence of FMNH2 as compared to in the absence of FMNH2. For either mechanism A or mechanism B to be operative, it is assumed that the FeNO moiety must be sufficiently activated and/or oriented toward another NO/FeNO to lead to productive N–N coupling.

Figure 1.

Plausible mechanisms for N2O formation by FDPnor.

Only a small number of synthetic nonheme iron complexes are known to mediate the reduction of NO to N2O.[7] Two dinuclear dinitrosyl iron ({FeNO7})2 complexes were shown to produce N2O upon 1e– or 2e– reduction.[7c, 7i, 7o] It was also shown that a dinuclear mononitrosyl iron (FeII{FeNO}7) complex can be reduced chemically or electrochemically to produce N2O.[7h] These studies lend support to mechanism A, in which the {FeNO}7 intermediate(s) are reduced prior to N–N coupling and N2O production. The first example of a nonheme iron model complex that was capable of carrying out the direct reduction of NO to N2O in the absence of an exogenous reductant was reported in 2014.[8] In this study, a dinuclear ({FeNO}7)2 complex, [Fe2(N-Et-HPTB)(O2CPh)(NO)2](BF4)2, was formed by addition of NO to a diiron precursor with 5-coordinate FeII centers, and produced N2O upon illumination with white light. Interestingly, the spectroscopic (infrared and resonance Raman (RR)) data provided strong evidence for the photoproduction of a mononitrosyl [FeII{FeNO}7) intermediate, which then underwent coupling with a second NO molecule to give N2O. A later study in 2018 showed that a dinuclear FeII2 complex was also capable of converting NO to N2O in the absence of exogenous reductant.[9] In this latter study, the saturated, 6-coordinate FeII centers were speculated to undergo dissociation of a carboxylate bridge prior to formation of a putative, reactive [{FeNO}7]2 intermediate. Although low-temperature spectroscopic studies revealed an [{FeNO}7]2 species, it was found to be inactive toward N2O production. It was proposed that the latter low-temperature species was trapped in an unproductive conformation for N–N bond formation. A similar observation was made for an [{FeNO}7]2 complex in which the anti-conformation of the two NO units negated the possibility of N2O release upon 1e– reduction.[10]

We were interested in determining the conditions necessary to carry out NO reduction by nonheme iron centers. It is our hypothesis that establishing these minimal requirements in well-characterized, synthetic complexes will provide knowledge of the critical elements needed for the catalytic, enzymatic process, and will also help support or refute proposed mechanistic pathways.[11] With these goals in mind, we focused our efforts on mononuclear nonheme iron complexes that can mediate the reduction of NO to N2O. We speculated that a mononuclear nonheme iron center, with an appropriate ligand environment, might have the minimal attributes needed to activate NO toward N–N bond formation and N–O cleavage to give N2O, circumventing the need for a dinuclear system by taking advantage of the diffusional reactivity accessible to small molecules. Our initial efforts led to a sulfur-ligated mononuclear iron complex ([FeII(N3PyS)]+) that supported the binding of NO in a rare series of redox-interconvertible {FeNO}6−8 species with identical ligand environments.[12] Reversible one-electron reduction of the {FeNO}7 complex gave an {FeNO}8 complex, which then decayed to produce N2O in sub-stoichiometric yield (54%).[13] This result lent support to the two-electron reduced pathway in mechanism A (Figure 1), which requires reduction to {FeNO}8 prior to N2O formation. It also provided initial evidence that a dinuclear scaffold was not required for reduction of NO to N2O by nonheme iron in a small-molecule system.

Motivated by our success with the 1e– reduced, mononuclear {FeNO}8 complex, we wondered whether NO reduction might be achieved by an appropriate mononuclear {FeNO}7 complex, in the absence of any exogenous reductants. Our criteria for an appropriate system included 1) a five-coordinate FeII precursor with N/O donors in the primary coordinating sphere, 2) enough steric encumbrance to stabilize mononuclear FeNO species, and 3) an electron-donating ligand environment to help activate bound NO toward N–N coupling and N-O cleavage. These criteria were fulfilled by [FeII(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (1), which we have employed to prepare the new {FeNO}7 complex [Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (2). Importantly, complex 2 also rapidly produces N2O in THF upon addition of H2O, providing the first example of a mononuclear, nonheme {FeNO}7 complex that generates N2O in the absence of external reductants. In addition, vibrational analysis by RR reveals that 2 has a dramatically weakened N–O stretch for an {FeNO}7 (S = 3/2) species, and the N-O stretching frequency is nearly identical to that seen for the activated {FeNO}7 unit in the mononitrosyl intermediate of FDPnor.[14]

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of [FeII(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (1).

The synthesis of [FeII(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (1) is shown in Scheme 1. The disiloxide ligand[15] was selected because of the similarities with the anionic O-donors of FDPnor, and because it provides a stable chelate with steric protection by the Ph groups. We hypothesized that the strong σ-donating ability of the disiloxide donors would significantly activate an {FeNO}7 species toward N–N bond-forming reactivity. Mixing of K2[(OSiPh2)2O] in THF with an equimolar purple solution of [FeII(Me3TACN)(CH3CN)3](OTf)2[16] in CH3CN was followed by workup and crystallization in pentane/THF to give pale blue crystals of 1 (35%).

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of Complexes 1 and 2

X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed that 1 is a 5-coordinate, mononuclear FeII complex bound by the Me3TACN and [(OSiPh2)2O]2- ligands in a distorted square pyramidal geometry (τ= 0.29).[17] The two Fe–O distances are nearly identical, and the Fe–NTACN distances are similar to those seen for other FeII(Me3TACN) complexes (Figure 2).[18] The cyclic voltammogram (CV) of 1 in MeCN shows a quasi-reversible wave at E1/2 = –0.90 V (vs Fc+/Fc; ΔEpp = 0.12 mV) (Figure S3), assigned to the FeIII/II redox potential and is consistent with an electron-rich metal center for 1. The zero-field Mössbauer spectrum of a frozen sample of 57Fe-1 in THF is shown in Figure 2. A sharp quadrupole doublet with δ = 0.97 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 1.98 mm s−1 is observed, consistent with a high-spin FeII species.

Figure 2.

(Left) Displacement ellipsoid plot (50% probability level) for 1 at 110(2) K. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å): Fe1–O1, 1.9402(16), Fe1–O2, 1.9458(13), Fe1–N1, 2.265(6), Fe1–N2, 2.280(6), Fe1–N3, 2.212(6). (Top-right) Mössbauer spectrum of 57Fe-1 (80 K). Data: black circles; best fit: red line.

Reactivity of NO(g) with 1 and characterization of [Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (2).

Addition of NO(g) to 1 in THF or 2-MeTHF forms a new species (2) with UV-vis absorption peaks at 446 nm (ε ~ 850 M–1cm–1), 570 nm (ε ~ 350 M–1cm–1), (Figure 3), and a 1H-NMR spectrum with paramagnetically shifted resonances distinct from those of 1. (Figure S4). In contrast to 1, the CV of 2 shows only irreversible redox events at negative potentials (Figure S5). Complex 2 is stable to sparging with Ar(g), indicating that the binding of NO to Fe is not reversible. Complex 2 immediately decays upon exposure to aerobic conditions, and adequate care was thus taken for further characterization.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra for 1 (1.4 mM) (black line) after addition of NO(g) to form 2 (green line) in THF. Inset: EPR spectrum of 2 in 2-MeTHF recorded at 8 K, 9.21 GHz.

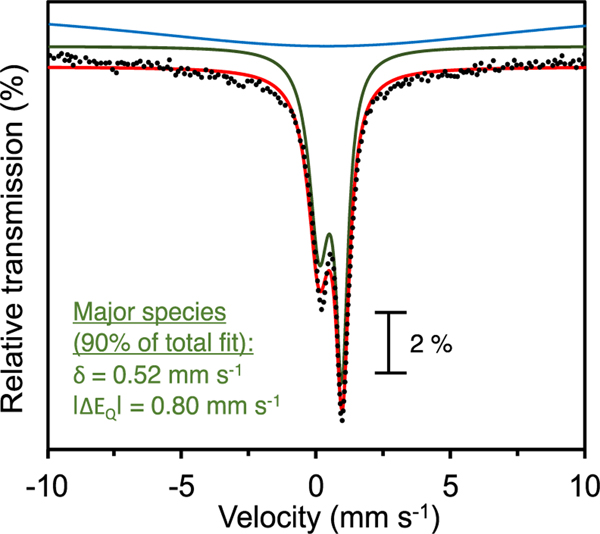

The EPR spectrum obtained for 2 in 2-MeTHF exhibits g-values at g = [4.08, 3.93, 1.99], which are typical of {FeNO}7 (S = 3/2) centers (Figure 3 inset).[19],[11a, 12] Mössbauer spectroscopy for the reaction of 1 with NO(g) shows a broad doublet with δ = 0.52 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 0.80 mm s−1 (Figure 4).[20],[21] The asymmetry in the intensity is due to vibrational anisotropy observed commonly in low symmetry systems.[22] DFT calculations (vide infra) yield theoretical values of δ = 0.44 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 0.99 mm s−1 for the {FeNO}7 complex 2, in reasonable agreement with experiment. The isomer shift for complex 2 is lower than that observed for the {FeNO}7 unit in the deflavo-(FDP)NO (δ = 0.68 mm s−1) suggesting a stronger polarization of the Fe–NO center towards FeIII-NO–.[23]

Figure 4.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum (80 K in frozen THF) of 2. Experimental data are plotted as black dots and best fits are overlaid as solid lines. The major species (δ = 0.52 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 0.80 mm s−1, 90 %) is shown as a green line. A second broad sub-component with δ = 0.6 mm s−1, |ΔEQ|= 1.00 mm s−1, ГR= ГL = 6.0 (blue line) was added to represent the intermediate relaxation of the doublet at 80 K.

A series of RR spectra obtained for 2 are shown in Figure 5. Frozen solutions of 2 in THF reveal a RR band at 1680 cm–1 which shifts to 1648 (Δν = –32 cm–1) and 1609 cm–1 (Δν = –71 cm−1) upon labeling with 15NO and 15N18O, respectively. These downshifts are in good agreement with a simple harmonic oscillator model for ν(NO), and thus, the 1680 cm−1 band is assigned as the ν(NO) mode. Complex 2 displays one of the lowest energy ν(NO) vibrations observed for a high-spin (S = 3/2) {FeNO}7 complex, which typically range between 1700 and 1840 cm−1 (Table 1).[21], [24] The low ν(NO) indicates that 2 contains a highly activated nitrosyl ligand for an {FeNO}7 (S = 3/2) species, and is consistent with our hypothesis that the strongly donating ancillary ligands of the disiloxide chelate would lead to potent activation of the FeNO unit.[14, 25] Complex 2 also provides a relatively rare example of an {FeNO}7 species for which ν(Fe–NO) is observed. The Fe–NO stretch is seen at 460 cm−1 and shifts to 453 and 447 cm−1 with 15NO and 15N18O, respectively. A weaker signal at 915 cm−1, that shifts −40 cm−1 with 15N18O, is assigned to a combination mode of the stretching and bending vibrations indicating that the fundamental δ(Fe-N-O) occurs at 455 cm-1. Similar detection of [ν(Fe–NO)+δ(Fe-N-O)] combination mode was reported previously in Fe(NO)(EDTA) and several nonheme diiron proteins including deflavo-FDP(NO)2.[5a, 8, 26]

Figure 5.

Low-temperature RR spectra of 2-NO (black), 2-15NO (red), and 2-15N18O (blue) in THF obtained with a 458-nm laser excitation. The difference spectra are shown in green.

Table 1.

Vibrational Data for Selected Six-Coordinate Nonheme {FeNO}7 (S = 3/2) Complexes.

| Complex | ν(NO) (cm−1) | ν(Fe–NO) (cm−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)(OSiPh2)2O)] | 1680 | 460 | This work |

| Deflavo-FDP(NO) | 1681 | 451 | [14] |

| [Fe(NO)(SMe2N4(tren)]+ | 1685 | - | [24b] |

| [Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)(N3)2] | 1690 | 436 | [19] |

| [Fe(NO)(BMPA-Pr)(Cl)][a] | 1726 | 484 | [28] |

| Deflavo-FDP(NO)2 | 1749 | 459 | [14] |

| [Fe(NO)N3PyS]BF4 | 1768 | - | [11a, 12, 29] |

| [Fe2(BPMP)(OPr)(NO)2]2+[e] | 1768 | - | [7i] |

| [Fe(NO)(N3PySEtCN2Ph)](BF4)2 | 1776 | - | [11c] |

| [Fe2(N-Et-HPTB)(NO)2(O2CPh)](BF4)2 [f] | 1784 | 492 | [8] |

| [Fe2(N-EtHPTB)(NO)2(DMF)2](BF4)3 | 1798 | - | [7o] |

| [Fe2(N-Et-HPTB)(NO)(DMF)3](BF4)3 | 1810 | 492 | [7h, 8] |

| [Fe(NO)(TPA)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 | 1810 | 502 | [28] |

| Fe(T1Et4iPrIP)(THF)(NO)(OTf)](OTf) | 1831 | - | [30] |

BMPA-Pr = N-propano-ate-N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine

T1Et4iPrIP T1Et4iPrIP = Tris(1-ethyl-4-isopropyl-imidazolyl)phosphine

TPA = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine and BF = benzoylformate

TLA = tris((6-methyl-2-pyridyl)methyl)amine

BPMP = 2,6-bis[[bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amino] methyl]-4-methylphenol

Et-HPTB = N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-(l-ethylbenzimidazolyI))-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane.

Calculations performed on FDPnor, as well as on synthetic models, suggest that a decrease in the energy barrier for N–N bond formation is expected upon enhancement of the nitroxyl (NO–) character of an FeNO center.[27] The weakened N–O vibration of 1681 cm–1 seen for the mononitrosyl form of FDPnor suggests a fairly polarized FeIII-NO– unit.[14] This enhanced nitroxyl character was partly attributed to an interaction of the bound NO group with the second FeII site. The ν(NO) and ν(Fe–NO) values for 2 are in excellent agreement with ν(NO) = 1681 cm–1 and ν(Fe–NO) = 451 cm–1 for deflavo-FDP(NO),[14] and the ν(N–O) mode for 2 is indicative of a same degree of N-O bond activation. We surmise that the mononuclear complex 2 does not require a second metal site to activate NO to the same extent as the protein because of the strongly donating anionic oxygen ligands in the primary coordination sphere. Electronic donation to the Fe center from the ancillary ligands is known to lower the ability of Fe to accept π-donation from π*(NO),[28] which leads to an increase in the π*-antibonding population and weakening of the N–O bond. The decrease in the π*-antibonding donation to the iron also results in a weak Fe–NO bond.[21, 28] Our strategy to use electronically-enriched ligand environments for NO activation by nonheme iron is supported by the vibration data.

Attempts to isolate 2 in a pure crystalline form were unsuccessful. We turned to X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) for geometric and electronic structural characterization of 2. Fitting of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for 2 is consistent with a six-coordinate Fe center with three N/O-scatterers at 2.32 Å and two N/O-scatterers at 1.97 Å (Table S1). An additional Fe–N/O scattering path with a distance of 1.76 Å accords with the Fe–NO distance expected for an S=3/2 {FeNO}7 complex. The pre-edge of 2 is blue-shifted relative to 1 consistent with a strengthened ligand field upon increase of coordination number from 5 to 6. The blue shift of the rising edge for 2 relative to 1 suggests diminished electron density at Fe consistent with delocalization of electron density from Fe to NO (Figure 6). Taken together, the XAS data confirm the structural integrity of 2 in solution as a mononuclear {FeNO}7 complex.

Figure 6.

Fe K-edge X-ray absorption near edge (XANES) spectra of [FeII(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (1, black line) and [Fe(NO)(Me3TACN)((OSiPh2)2O)] (2, red line).

Geometry optimization of 2 by DFT (BP86/6–311g*) yielded an intact six-coordinate structure around the iron center, with three nitrogen atoms, two oxygen atoms, and an axial nitrosyl group, as supported by the experimental results from EXAFS. Frequency calculation predicts a low value of 1629 cm−1 for the NO vibration, and a shift to 1598 cm−1 for the 15N18O isotopomer, in agreement with a simple harmonic oscillator model. The Fe–NO and N–O bond lengths were calculated to be 1.738 Å and 1.199 Å respectively. The Fe–N–O angle (=144.16°) was found to be significantly bent, which accords with the low N–O vibration. A higher negative spin density was observed on the nitrogen atom as compared to the oxygen atom of the NO group.[7j, 7l] The absorption spectrum for 2 was simulated by using the TDDFT method with the CAM-B3LYP range-separated functional (19–65% Hartree-Fock exchange) and an Ahlrichs triple zeta basis set (def2-TZVP).[31] A correction of the simulated spectra by 0.56 eV was required to match the experimental spectral features, to account for the well-established over-estimation of the absolute transition frequency by TDDFT calculations.[32] Transition difference density plots were analyzed for interpretation of the vertical transitions under the major absorption features as shown in Figure 7. The experimental and simulated spectrum are found to be in good agreement with each other. The intense band at 446 nm could be assigned to excitations within the β- spin manifold. However, the less intense band at 570 nm contains a group of excitations occurring within both the α- and β-spin manifolds which coalesce into one due to their closeness in energy. For both cases, the major contribution arises from a ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) originating from the NO-(π*) to an admixture of Fe(III)-dxz/yz orbitals. The band at 570 nm has additional contributions due to the ligand-ligand charge transfer excitations arising from the O(siloxide)/ N(Me3TACN) donors to the NO(π*) within the α-manifold.

Figure 7.

TD-DFT simulated UV-vis absorption spectrum for 2 (dashed purple line) overlaid with the experimental spectrum (red line). The computed spectral excitations are shown as black sticks. Electron difference density map for the computed transition (λmax = 447 nm) is shown with the green and red regions indicating gain and loss of electron density respectively.

Formation of N2O from 2.

The {FeNO}7 complex 2 is stable at room temperature (23 °C) in dry solvent (e.g. THF, CH3CN) for at least 2 h, as seen by UV-vis spectroscopy. However, addition of a small amount of water to a THF solution of 2 (1:10 H2O:THF v:v) results in the rapid decay of 2, as seen by the loss of absorbance at 570 nm (Figure S6). Headspace analysis of the reaction mixture after addition of H2O was carried out by gas chromatography (GC), and revealed the formation of N2O. Quantitation against an N2O calibration curve showed that N2O was formed in 30% yield based on a 2:1 Fe:N2O ratio (Scheme 2). Formation of N2O was observed in similar yield when 2 is generated by the controlled addition of NO(g) pre-dissolved in THF. The controlled addition of solubilized NO in THF helped in limiting excess NO(g) in the reaction mixture, allowing only the minimum amount required to attain full formation of 2. The production of N2O was the same under these conditions, showing that excess NO(g) is not required for N2O formation. In the absence of H2O, no N2O formation was observed, and similarly, no N2O was observed in the absence of the metal complex. We have made efforts to pinpoint the role of water by testing other Bronsted acids (e.g. HCl, HBF4, CF3CO2H, CF3SO2H), but the addition of these acids led to rapid bleaching of the solution. Weaker acids (e.g. HOAc, MeOH) did not give N2O formation. Addition of isotopically labeled 15NO (98% 15N) to give 15NO-labeled 2 and examination of the same reaction by GC mass spectrometry (GC-MS) revealed a major peak at 46 m/z, corresponding to 15N2O. The final reaction mixture was tested for nitrite ion via a Griess assay, which was shown to be negative. This result, along with other control reactions in the absence of iron, provide good evidence that disproportionation of NO to N2O and NO2- may not be occurring. Taken together, the data show that 1 directly converts NO to N2O without the addition of an exogenous reductant. There is only one other example of a mononuclear FeII species in a heme-based environment that produces N2O in a similar manner.[7j]

Scheme 2.

N2O formation from 2.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of the final reaction mixture showed disappearance of 2, and no other well-resolved species could be observed. The Mössbauer spectrum is poorly resolved and appears to contain a mixture of species (Figure S11). The EPR spectrum of the reaction mixture also suggests a potential mixture of products (Figure S12). Attempts to analyze the final reaction mixture by RR spectroscopy was unsuccessful due to high background signals. Thus we are unable to identify the final iron decay products in the reaction mixture, but the production of N2O is reproducible under these conditions.

Formation of N2O from NO in eq 1 requires the presence of H+, consistent with the need for the addition of H2O to trigger production of N2O from 2. The exogenous water may also help facilitate the reaction by activating the FeNO moiety, or enhancing either the formation or decay of related intermediates through hydrogen bonding. Mutation of a Tyr to Phe residue in the active site of FDPnor resulted in loss of catalytic activity, and DFT calculations implicated the Tyr as providing a key hydrogen bond to an N–N coupled hyponitrite (ONNO2-) intermediate during NO reduction.[27c, 33] Hydrogen bonding between the solvent and NO-derived intermediates has also been implicated as an important factor in other synthetic complexes.[7g, 7n]

Conclusion

A new 5-coordinate FeII complex, 1, was synthesized. It was shown that 1 reacts with NO to yield a 6-coordinate, S = 3/2, {FeNO}7 complex 2, which contains a highly activated NO ligand. Complex 2 has been characterized by UV-vis, 1H-NMR, resonance Raman, EPR, Mössbauer, XAS, and DFT studies. The N–O and Fe–NO vibrations for 2 are observed at 1680 cm–1 and 460 cm–1 respectively, close to the ν(NO) = 1681 cm–1 and ν(Fe-NO) = 451 cm–1 observed for the mononitrosyl deflavo-FDP(NO), and indicates a similar degree of NO activation to that observed in the protein. Complex 2 reacts rapidly with excess water in THF to yield N2O, and thus is a rare example of a mononuclear {FeNO}7 complex that can mediate the conversion of NO to N2O without an exogenous reductant. Given that 2 is stable in solution even under vigorous Ar(g) sparging, it is reasonable to assume that NO dissociation from 2 is negligible. The production of N2O is also unaffected by the presence of excess NO(g). Although the mechanism of N2O formation has yet to be studied in detail, these observations suggest the possibility of a bimolecular reaction between intact {FeNO}7 monomers to give N2O. However, further studies will be required to support this proposed mechanism. This work shows that an appropriately designed, electron-rich ligand environment for nonheme iron can promote substantial activation of small molecules like NO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The NSF (CHE1566007 to D.P.G.) and NIH (GM124908 to K.M.L. and GM074785 to P.M.L.) are gratefully acknowledged for financial support. J.B.G. would like to thank JHU for funding through the Sonneborn Fellowship. A.D sincerely thanks Jessica Zarenkiewicz and Prof. J. P. Toscano (JHU Chemistry) as well as Zhuoqun Zhang and Prof. A. S. Hall (JHU Material Science & Engineering) for the use of GC/GC-MS instrumentation (headspace gas analysis). XAS data were obtained at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P30GM133894).

References

- [1].a) Wasser IM, de Vries S, Moënne-Locco P, Schröder I, Karlin KD, Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1201–1234; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Szaciłowski K, Chmura A, Stasicka Z, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 2408–2436; [Google Scholar]; c) Tennyson AG, Lippard SJ, Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1211–1220; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Khatua S, Majumdar A, J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 142, 145–153; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Timmons AJ, Symes MD, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6708–6722; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wright AM, Hayton TW, Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 9330–9341; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Romão CV, Vicente JB, Borges PT, Frazão C, Teixeira M, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 21, 39–52; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Ferousi C, Majer SH, DiMucci IM, Lancaster KM, Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 5252–5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Kurtz JDM, Dalton Trans. 2007, 4115–4121; [Google Scholar]; b) Weitz AC, Giri N, Caranto JD, Kurtz DM, Bominaar EL, Hendrich MP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12009–12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arikawa Y, Onishi M, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Enemark JH, Feltham RD, Coord. Chem. Rev. 1974, 13, 339–406. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Hayashi T, Caranto JD, Wampler DA, Kurtz DM, Moënne-Loccoz P, Biochemistry 2010, 49, 7040–7049; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Caranto JD, Weitz A, Giri N, Hendrich MP, Kurtz DM, Biochemistry 2014, 53, 5631–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Caranto JD, Weitz A, Hendrich MP, Kurtz DM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7981–7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Xu N, Campbell ALO, Powell DR, Khandogin J, Richter-Addo GB, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2460–2461; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wright AM, Wu G, Hayton TW, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9930–9933; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng S, Berto TC, Dahl EW, Hoffman MB, Speelman AL, Lehnert N, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4902–4905; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Berto TC, Xu N, Lee SR, McNeil AJ, Alp EE, Zhao J, Richter-Addo GB, Lehnert N, Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 6398–6414; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Brozek CK, Miller JT, Stoian SA, Dincă M, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7495–7501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Hoerger CJ, La Pierre HS, Maron L, Scheurer A, Heinemann FW, Meyer K, Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 10854–10857; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Wijeratne GB, Hematian S, Siegler MA, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13276–13279; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Jana M, Pal N, White CJ, Kupper C, Meyer F, Lehnert N, Majumdar A, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14380–14383; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) White CJ, Speelman AL, Kupper C, Demeshko S, Meyer F, Shanahan JP, Alp EE, Hu M, Zhao J, Lehnert N, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2562–2574; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Abucayon EG, Khade RL, Powell DR, Zhang Y, Richter-Addo GB, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4204–4207; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Ferretti E, Dechert S, Demeshko S, Holthausen MC, Meyer F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 1705–1709; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Kundu S, Phu PN, Ghosh P, Kozimor SA, Bertke JA, Stieber SCE, Warren TH, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1415–1419; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Wu W-Y, Hsu C-N, Hsieh C-H, Chiou T-W, Tsai M-L, Chiang M-H, Liaw W-F, Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 9586–9591; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Wijeratne GB, Bhadra M, Siegler MA, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17962–17967; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lehnert N, Majumdar A, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6600–6616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jiang Y, Hayashi T, Matsumura H, Do LH, Majumdar A, Lippard SJ, Moënne-Loccoz P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12524–12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dong HT, White CJ, Zhang B, Krebs C, Lehnert N, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13429–13440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kindermann N, Schober A, Demeshko S, Lehnert N, Meyer F, Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 11538–11550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) McQuilken AC, Matsumura H, Dürr M, Confer AM, Sheckelton JP, Siegler MA, McQueen TM, Ivanović-Burmazović I, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3107–3117; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Confer AM, Vilbert AC, Dey A, Lancaster KM, Goldberg DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7046–7055; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Confer AM, Sabuncu S, Siegler MA, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP, Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 9576–9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dey A, Confer AM, Vilbert AC, Moënne-Loccoz P, Lancaster KM, Goldberg DP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13465–13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Confer AM, McQuilken AC, Matsumura H, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10621–10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hayashi T, Caranto JD, Matsumura H, Kurtz DM, Moënne-Loccoz P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6878–6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Schax F, Suhr S, Bill E, Braun B, Herwig C, Limberg C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1352–1356; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wind M-L, Hoof S, Herwig C, Braun-Cula B, Limberg C, Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 5743–5750; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Beckmann F, Kass D, Keck M, Yelin S, Hoof S, Cula B, Herwig C, Krause KB, Ar D, Limberg C, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2021, 647, 960–967. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Blakesley DWP, Sonha C; Hagen, Karl S., Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van Rijn J, Verschoor GC, J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Komuro T, Matsuo T, Kawaguchi H, Tatsumi K, Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 5340–5347; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gordon JB, McGale JP, Prendergast JR, Shirani-Sarmazeh Z, Siegler MA, Jameson GNL, Goldberg DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14807–14822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].C. A. Brown, M. A. Pavlosky, T. E. Westre, Y. Zhang, B. Hedman, K. O. Hodgson, E. I. Solomon, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 715–732. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ye S, Price JC, Barr EW, Green MT, Bollinger JM, Krebs C, Neese F, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4739–4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Berto TC, Speelman AL, Zheng S, Lehnert N, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 244–259. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) McGrath AC, Cashion JD, Hyperfine Interact. 2006, 168, 1103–1107; [Google Scholar]; b) Reguera E, Yee-Madeira H, Demeshko S, Eckold G, Jimenez-Gallegos J, Z. Phys. Chem. 2009, 223, 701–711; [Google Scholar]; c) Kaczmarzyk T, Jackowski T, Dziliński K, Sinyakov GN, Nukleonika 2007, 52, S93–S98; [Google Scholar]; d) Varnek VA, Lavrenova LG, J. Struct. Chem. 1995, 36, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weitz AC, Giri N, Frederick RE, Kurtz DM, Bominaar EL, Hendrich MP, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11704–11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Conradie J, Quarless DA, Hsu HF, Harrop TC, Lippard SJ, Koch SA, Ghosh A, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10446–10456; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Villar-Acevedo G, Nam E, Fitch S, Benedict J, Freudenthal J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bhagi-Damodaran A, Reed JH, Zhu Q, Shi Y, Hosseinzadeh P, Sandoval BA, Harnden KA, Wang S, Sponholtz MR, Mirts EN, Dwaraknath S, Zhang Y, Moënne-Loccoz P, Lu Y, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2018, 115, 6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lu S, Libby E, Saleh L, Xing G, Bollinger JM, Moënne-Loccoz P, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 9, 818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Blomberg LM, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 12, 79–89; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Van Stappen C, Lehnert N, Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4252–4269; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lu J, Bi B, Lai W, Chen H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3795–3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Berto TC, Hoffman MB, Murata Y, Landenberger KB, Alp EE, Zhao J, Lehnert N, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16714–16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McQuilken AC, Ha Y, Sutherlin KD, Siegler MA, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Jameson GNL, Goldberg DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14024–14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li J, Banerjee A, Pawlak PL, Brennessel WW, Chavez FA, Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 5414–5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Weigend F, Ahlrichs R, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Barton D, König C, Neugebauer J, J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 164115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Neese F, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 526–563. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Biswas S, Kurtz DM, Montoya SR, Hendrich MP, Bominaar EL, ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8177–8186. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.