Abstract

Low socioeconomic position (SEP) across the lifecourse is associated with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM). We examined whether these economic disparities differ by race and sex. We included 5,448 African American (AA) and white participants aged ≥45 years from the national (United States) REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort without T2DM at baseline (2003–07). Incident T2DM was defined by fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, random glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or using T2DM medications at follow-up (2013–16). Derived SEP scores in childhood (CSEP) and adulthood (ASEP) were used to calculate a cumulative (CumSEP) score. Social mobility was defined as change in SEP. We fitted race-stratified logistic regression models to estimate the association between each lifecourse SEP indicator and T2DM, adjusting for covariates; additionally, we tested SEP-sex interactions. Over a median of 9.0 (range 7–14) years of follow-up, T2DM incidence was 167.1 per 1000 persons among AA and 89.9 per 1000 persons among white participants. Low CSEP was associated with T2DM incidence among AA (OR=1.61; 95%CI 1.05–2.46) but not white (1.06; 0.74–2.33) participants; this was attenuated after adjustment for ASEP. In contrast, low CumSEP was associated with T2DM incidence for both racial groups. T2DM risk was similar for stable low SEP and increased for downward mobility when compared with stable high SEP in both groups, whereas upward mobility increased T2DM risk among AAs only. No differences by sex were observed. Among AAs, low CSEP was not independently associated with T2DM, but CSEP may shape later-life experiences and health risks.

Keywords: Lifecourse socioeconomic position, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, African American, social mobility

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), racial minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM),[1] and the risk for T2DM increases with decreasing socioeconomic position (SEP).[2] The mechanisms by which social gradients in chronic disease risks arise have been conceptualized as operating at different stages across the lifecourse from in utero to adulthood.[3–5] Three theoretical lifecourse hypotheses have been proposed. First, the critical/sensitive period hypothesis posits that during specific periods of development (e.g. childhood), adverse physical and social exposures may have long-lasting effects on the structure and function of systems, organs, and tissues. Such ‘biological programming’ in early life may predispose individuals to increased risk of chronic conditions, such as T2DM, later in life. The ‘accumulation of risk’ hypothesis contends that the frequency and duration of SEP exposures across the lifecourse have a cumulative impact on risk of chronic disease in later life. Finally, the social mobility model proposes that the health effects of childhood/early life SEP may be altered by subsequent SEP trajectories.

The enduring legacy of structural racism and discrimination in our society has maintained socioeconomic inequalities by race for generations. Lost incomes and inheritances due to slavery[6, 7], and segregation[8] and its sequelae (including discriminatory housing[9] and employment[10] policies and racial inequities in education[11]), help to explain why the average Black family’s wealth is less than15 percent of the wealth of the average white family[12]. Given these starkly different experiences, it is critical to understand whether and how the relationship between SEP and health operates differently in these groups. While lifecourse hypotheses have been used to examine the relationship between SEP and T2DM among adults in the US and elsewhere.[13–24] whether this relationship varies by race is unclear.[6, 7] Several prior studies of SEP and T2DM did not report racial or ethnic distribution of participants,[15, 16, 20–22, 24] or only included race as a covariate.[14, 17] Beckles et al used Jackson Heart Study data which consisted of African American (AA) participants only, so comparisons by race could not be made, but reported that childhood SEP was not associated with T2DM.[13] The findings from the Alameda County (CA) study, which reported associations between low early-life SEP and increased risk of incident T2DM for white but not AA participants, may not necessarily extend to larger, more geographically diverse or more recent cohorts. [18]

Prior evidence on sex modifying the effect of lifecourse SEP on T2DM has been equivocal. Several studies reported an association between early life SEP and T2DM among women only.[16, 17, 19]. Similarly, other examinations of lifecourse SEP hypotheses in relation to incident T2DM observed associations for cumulative SEP[21], and social mobility[13, 21] among women only. Conversely, Camelo et al (Brazil) reported associations between both cumulative SEP and social mobility and new-onset DM, particularly for men, as the associations for women were attenuated after adjustment for covariates[14], while Demakkakos’ examination of multiple SEP measures noted that adulthood SEP (wealth and subjective social status) was associated with incident DM among men (and women)[16]. Other analyses did not find interactions by sex in their observed SEP-DM associations. [20, 24].

The purpose of the present study was to test each of the lifecourse SEP hypotheses in a large, prospective cohort of AA and white adults. We examined whether low SEP during childhood or adulthood was associated with increased T2DM incidence, and assessed the association of cumulative lifecourse SEP and social mobility on T2DM incidence by race. Finally, we evaluated whether heterogeneity by sex was present in any lifecourse SEP-T2DM relationships observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and population

The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study is a national, prospective cohort study designed to investigate disparities in the incidence of stroke, cognitive decline, and cardiovascular risk factors among adults in the US.[25] By design, AA individuals and residents of the ‘Stroke Belt’ region (eight southern states with higher stroke mortality than the rest of the US)[25] were oversampled with enrollment of 30,239 community-dwelling individuals, age 45 years and older, between 2003 and 2007. Through a computer-assisted telephone interview, trained interviewers obtained demographic information, medical history and lifestyle factors including a selection of risk factors. A brief in-home physical exam was conducted to collect anthropometric and blood pressure measurements and biological samples. Participants were asked to complete self-administered questionnaires, including (1) a residential history questionnaire, which was used to derive a measure of lifetime residence in the ‘Stroke Belt’ region;[26] and (2) a dietary consumption questionnaire, which was used to derive the Mediterranean Diet score, a measure of adherence to a largely plant-based diet (cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, olive oil and fish).[27]

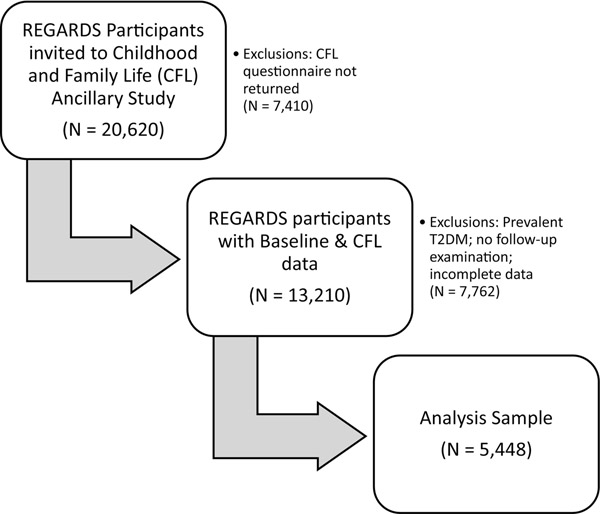

In July 2012, a Childhood and Family Life Factors ancillary study was begun to examine the relationships among early life exposures, family background and stroke. A questionnaire was mailed to the 20,620 participants who were still in active follow-up, and 13,210 were returned (64%). For this analysis we excluded participants with prevalent T2DM (n =2,467) those who did not have a follow-up examination (n=2,278), and those with incomplete data (n=3,017), for a final sample size of 5,448 adults (AA = 1,233; white =4,215) (Figure 1). The parent and ancillary studies were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board and the review boards of all participating institutions, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Study population flowchart.

Main variables

Outcome

Incident T2DM was defined by fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, random glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or use of T2DM medications, as ascertained at the follow-up examination (2013–2016).

Exposures

SEP indicators were conceptualized to represent measures of lifecourse SEP exposures for critical/sensitive periods (i.e. childhood and adulthood SEP), accumulation of risk (cumulative SEP) and changes in SEP trajectory (social mobility) [28].

Childhood SEP (CSEP) was measured by participant’s retrospective report of parent/caregiver 1) educational attainment and 2) material assets. Educational attainment of parent/caregiver was categorized and coded as <high school=0, high school/GED=1, >high school =2; (range, 0 to 2). For participants who lived with both parents, the parental education recorded was based on the highest level attained. Material assets of parent/caregiver during most of childhood was measured by whether or not they owned a house, owned other property, or had a car. Each were coded as yes = 1, no = 0 (range, 0 to 3). A CSEP score was calculated for each participant by summing the response codes for parental educational attainment and material assets (range, 0 to 5), with higher scores indicating higher SEP. CSEP was categorized as low (score = 0–1), medium (score = 2–3), or high (score =4–5).

Adult SEP (ASEP) was derived from 1) educational attainment of participant or of higher educated spouse (<high school, high school/GED, >high school),[29] and 2) annual household income (<$35K, $35K-$74K, ≥$75K) reported at baseline. An ASEP score (range, 0 to 4) was calculated by summing codes for participants’ education (0 to 2) and household income (0 to 2). ASEP was categorized as low (score=0–1), medium (score=2–3), or high (score=4).

Cumulative SEP (CumSEP) was derived by summing the CSEP and ASEP scores (range, 0 to 9), with higher scores indicating higher CumSEP. CumSEP was categorized as low (score=0–4), medium (score=5–6), or high (score=7–9).

Social Mobility.

Consistent with other studies of SEP trajectories and their association with incident T2DM,[13, 14, 17, 21, 22] social mobility was derived from CSEP and ASEP scores. We re-categorized the CSEP and ASEP indicators as binary variables [low (0–1) vs medium/high (2+)]. Then, we derived 4 SEP trajectories: 1) stable low (low CSEP and low ASEP); 2) upwardly mobile (low CSEP to medium/high ASEP); 3) downwardly mobile (medium/high CSEP to low ASEP); 4) stable high (medium/high CSEP and medium/high ASEP).

Covariates

Covariates included baseline demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, percentage of life lived in the Stroke Belt). We used lifetime residence in the Stroke Belt as a contextual variable because an analogous geographic patterning of excess diabetes risk (i.e., a ‘Diabetes Belt’) has been identified.[27] We also included an additional set of covariates for which causal direction is ambiguous i.e., they may have been influenced by past SEP, including T2DM risk factors: biologic (body mass index [BMI], waist circumference, inflammation biomarker high sensitivity C-reactive protein [CRP]); behavioral (physical activity [times/week to work up a sweat], dietary consumption [mean Mediterranean Diet score],[30, 31] cigarette smoking status [current, past, never], and alcohol consumption [current, past, never]).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted to compare the race-specific distributions of the SEP indicators and T2DM risk factors in the analytic sample. We calculated T2DM incidence as number of new cases per total number of respondents, according to each lifecourse SEP indicator and race.

We fit a series of multivariable logistic regression models to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to test the separate and simultaneous associations between SEP indicators and T2DM incidence among AA and white participants, respectively. Models were adjusted for demographic characteristics, and then for T2DM risk factors. To examine whether the lifecourse SEP effects varied by sex, we tested for significant (p <.05) SEP by sex interactions in the full models within each racial group. To handle excluded observations due to missing data, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the iterated chained equations approach to perform multiple imputations (5 imputed datasets) of all variables needed to derive the childhood and adulthood SEP scores and the Mediterranean Diet score. We then repeated the race-specific tests of associations between SEP indicators and incident T2DM and combined the results across the imputed datasets. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics, overall and stratified by race are presented in Table 1. AA participants were more likely than white participants to be younger, female, and to have lived a greater proportion of their lives in the ‘Stroke Belt’. AAs also had higher levels of adiposity and chronic inflammation. Low SEP scores in childhood and adulthood were more common among AAs than white participants; consequently AA participants also had a higher proportion of low CumSEP, and stable low and upwardly mobile SEP trajectories (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Nondiabetic Participants in the REGARDS Study, by Race

| AFRICAN AMERICAN (n =1,233) | WHITE (n = 4,215) | TOTAL (N = 5,448) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Value | (95% CI) | Value | (95% CI) | Value | (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age group (years),% | ||||||

| 45–54 | 16.7 | (14.7, 19.0) | 13.2 | (12.2, 14.2) | 14.0 | (13.1, 14.9) |

| 55–64 | 50.0 | (47.1,52.8) | 43.5 | (42.0, 45.1) | 45.0 | (43.6, 45.3) |

| ≥65 | 33.3 | (30.7, 36.0) | 43.3 | (41.8, 44.8) | 41.1 | (39.7, 42.4) |

| Female Sex, % | 70.5 | (67.8, 73.1) | 50.4 | (48.8, 51.9) | 54.9 | (53.6, 56.2) |

| Mean proportion of life in Stroke Belt | 0.49 | (0.47, 0.52) | 0.43 | (0.42, 0.44) | 0.44 | (0.43, 0.46) |

| T2DM risk factors | ||||||

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 30.5 | (30.2, 30.9) | 27.5 | (27.4, 27.7) | 28.2 | (28.1,28.4) |

| Mean waist circumference (cm) | 94.6 | (93.8, 95.4) | 91.9 | (91.5, 92.4) | 92.5 | (92.2, 92.9) |

| Mean CRP (mg/dL) | 5.0 | (4.6, 5.3) | 3.0 | (2.9, 3.2) | 3.5 | (3.4, 3.6) |

| Physical activity (times/week), % | ||||||

| None | 31.2 | (28.6, 33.9) | 24.2 | (22.9, 25.6) | 25.8 | (24.6, 27.0) |

| 1–3 | 42.4 | (39.6, 45.3) | 41.3 | (39.8, 42.8) | 41.6 | (40.3, 42.9) |

| ≥4 | 26.4 | (23.9, 28.9) | 34.5 | (33.0, 36.9) | 32.6 | (31.4, 33.9) |

| Mean Mediterranean Diet score | 4.7 | (4.6, 4.8) | 4.5 | (4.4, 4.6) | 4.55 | (4.5, 4.6) |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||

| Current | 12.9 | (11.1, 15.0) | 8.2 | (7.4, 9.1) | 9.3 | (8.5, 10.1) |

| Past | 36.9 | (34.1,39.7) | 41.2 | (39.7, 42.8) | 40.3 | (38.9, 41.6) |

| Never | 50.2 | (47.4, 53.1) | 50.6 | (49.0, 52.1) | 50.5 | (49.1,51.8) |

| Alcohol consumption, % | ||||||

| Current | 53.7 | (50.8, 56.5) | 68.6 | (67.2, 70.0) | 65.3 | (64.0, 66.5) |

| Former | 16.2 | (14.2, 18.4) | 9.8 | (8.9, 10.7) | 11.2 | (10.4, 12.1) |

| Never | 30.2 | (27.7, 32.8) | 21.6 | (20.4, 22.9) | 23.5 | (22.4, 24.7) |

Abbreviations: SEP, socioeconomic position; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein

Table 2.

Socioeconomic Position Characteristics of Nondiabetic Participants in the REGARDS Study, by Race

| AFRICAN AMERICAN (n =1,233) | WHITE (n = 4,215) | TOTAL (N = 5,448) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEP Characteristics | Value | (95% CI) | Value | (95% CI) | Value | (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||

| Childhood SEP | ||||||

| Parental educational attainment, % | ||||||

| Less than high school | 55.4 | (52.6, 58.3) | 30.4 | (29.0, 31.8) | 36.0 | (34.7, 37.3) |

| High school/GED | 19.6 | (17.4, 22.0) | 26.6 | (25.2, 27.9) | 25.0 | (23.8, 26.2) |

| More than high school | 24.9 | (22.5, 27.5) | 43.1 | (41.6, 44.6) | 39.0 | (37.7, 40.3) |

| Parent owned house, % | 56.7 | (53.8, 59.5) | 75.0 | (73.7, 76.3) | 70.9 | (69.6, 72.1) |

| Parent owned other property, % | 31.2 | (28.6, 33.9) | 29.7 | (28.4, 31.2) | 30.1 | (28.9, 31.3) |

| Parent had car, % | 68.9 | (66.2, 71.5) | 88.3 | (87.3, 89.3) | 84.0 | (83.0, 84.9) |

| Childhood SEP score, % | ||||||

| Low | 34.6 | (31.9, 37.3) | 13.1 | (12.1, 14.1) | 17.9 | (16.9, 19.0) |

| Medium | 43.0 | (40.2, 45.9) | 46.0 | (44.5, 47.5) | 45.3 | (44.0, 46.7) |

| High | 22.5 | (20.1,24.9) | 40.9 | (39.4, 42.4) | 36.8 | (35.5, 38.1) |

| Adult SEP | ||||||

| Own educational attainment, % | ||||||

| Less than high school | 5.0 | (3.8, 6.4) | 2.8 | (2.3, 3.3) | 3.3 | (2.8, 3.8) |

| High school | 23.2 | (20.8, 24.7) | 18.8 | (17.6, 20.0) | 19.8 | (18.7, 20.9) |

| More than high school | 71.8 | (69.2, 74.4) | 78.5 | (77.2, 79.7) | 77.0 | (75.9, 78.1) |

| Annual household income, % | ||||||

| Less than $35K | 41.7 | (38.9, 44.5) | 27.2 | (25.9, 28.6) | 30.5 | (29.2, 31.7) |

| $35K–74K | 40.9 | (38.1,43.8) | 40.1 | (38.6, 41.6) | 40.3 | (39.0, 41.6) |

| $75K+ | 17.4 | (15.3, 19.7) | 32.7 | (31.3, 34.1) | 29.2 | (28.0, 30.5) |

| Adulthood SEP score, % | ||||||

| Low | 19.2 | (17.0, 21.6) | 11.8 | (10.8, 12.8) | 13.5 | (12.6, 14.4) |

| Medium | 64.7 | (61.9, 67.4) | 58.1 | (56.6, 59.6) | 59.6 | (58.3, 60.9) |

| High | 16.1 | (14.0, 19.0) | 30.1 | (28.7, 31.5) | 26.9 | (25.7, 28.1) |

| Cumulative SEP score, % | ||||||

| Low | 46.3 | (43.5, 49.1) | 23.5 | (22.2, 24.8) | 28.7 | (27.5, 29.9) |

| Medium | 33.7 | (31.1,36.5) | 35.4 | (33.9, 36.9) | 35.0 | (33.8, 36.3) |

| High | 20.0 | (17.8, 22.3) | 41.1 | (39.6, 42.6) | 36.3 | (35.1,37.6) |

| Social mobility, % | ||||||

| Stable low | 10.6 | (9.0, 12.5) | 3.3 | (2.8, 3.9) | 5.0 | (4.4, 5.6) |

| Upwardly mobile | 24.1 | (21.7, 26.6) | 9.7 | (8.8, 10.6) | 12.9 | (12.0, 13.8) |

| Downwardly mobile | 8.7 | (7.2, 10.4) | 8.6 | (7.8, 9.5) | 8.6 | (7.9, 9.4) |

| Stable high | 56.6 | (53.8, 59.4) | 78.4 | (77.2, 79.7) | 73.5 | (72.3, 74.7) |

Abbreviations: SEP, socioeconomic position; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

During a median of 9.0 (range 7–14) years of follow-up, 585 participants developed T2DM, yielding a crude cumulative incidence of 107.4 per 1000 persons (Table 3). Incidence of T2DM was higher in AAs than white participants overall, and at each level of SEP. In the total sample, T2DM incidence showed an inverse gradient with CSEP and ASEP. Stratified by race, a similar pattern was seen in both CSEP and ASEP for AAs and for ASEP among white individuals but the tests for linear trend were not statistically significant. Stratification by social mobility revealed that downwardly mobile participants had the highest T2DM incidence in both groups.

Table 3.

Crude Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes according to Lifecourse Socioeconomic Position Indicators in the REGARDS Study, by Race

| AFRICAN AMERICAN | WHITE | TOTAL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Sample (N) | Cases (n) | Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) | Sample (N) | Cases (n) | Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) | Sample (N) | Cases (n) | Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Total | 1233 | 206 | 167.1 (144.3, 189.9) | 4215 | 379 | 89.9 (80.9, 99.0) | 5448 | 585 | 107.4 (98.7, 116.1) |

| Childhood SEP | |||||||||

| Low | 428 | 85 | 198.6 (156.4, 240.8) | 547 | 46 | 84.1 (59.8, 108.4) | 975 | 131 | 134.4 (111.4, 157.4) |

| Medium | 526 | 84 | 159.7 (125.5, 193.9) | 1946 | 196 | 100.7 (86.6, 114.8) | 2472 | 280 | 113.3 (100.0, 126.5) |

| High | 279 | 37 | 132.6 (89.9, 175.4) | 1722 | 137 | 79.6 (66.2, 92.9) | 2001 | 174 | 87.0 (74.0, 99.9) |

| P for linear trend | 0.066 | 0.869 | 0.040 | ||||||

| Adult SEP | |||||||||

| Low | 238 | 48 | 201.7 (144.6, 258.7) | 502 | 68 | 135.5 (103.3, 167.7) | 740 | 116 | 156.8 (128.2, 185.3) |

| Medium | 795 | 139 | 174.8 (145.8, 203.9) | 2442 | 228 | 93.4 (81.3, 105.5) | 3237 | 367 | 113.4 (101.8, 124.9) |

| High | 200 | 19 | 95.0 (52.3, 137.7) | 1271 | 83 | 65.3 (51.3, 79.4) | 1471 | 102 | 69.3 (55.9, 82.8) |

| P for linear trend | 0.178 | 0.073 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Cumulative SEP | |||||||||

| Low | 571 | 115 | 201.4 (164.6, 238.2) | 990 | 118 | 119.2 (97.7, 140.7) | 1561 | 233 | 149.3 (130.1, 168.4) |

| Medium | 416 | 62 | 149.0 (111.9, 186.1) | 1492 | 130 | 87.1 (72.2, 102.1) | 1908 | 192 | 100.6 (86.4, 114.9) |

| High | 246 | 29 | 117.9 (75.0, 160.8) | 1733 | 131 | 75.6 (62.7, 88.5) | 1979 | 160 | 80.9 (68.3, 93.4) |

| P for linear trend | 0.093 | 0.169 | 0.152 | ||||||

| Social Mobility | |||||||||

| Stable low | 131 | 25 | 190.8 (127.5, 268.7) | 140 | 15 | 107.1 (61.2, 170.6) | 271 | 40 | 147.6 (107.6, 195.5) |

| Upwardly mobile | 297 | 60 | 202.0 (157.8, 252.2) | 407 | 31 | 76.2 (52.3, 106.4) | 704 | 91 | 129.3 (105.4, 156.3) |

| Downwardly mobile | 107 | 23 | 215.0 (141.4, 304.9) | 362 | 53 | 146.4 (111.6, 187.1) | 469 | 76 | 162.0 (129.9, 198.6) |

| Stable high | 698 | 98 | 140.4 (115.5, 168.4) | 3306 | 280 | 84.7 (75.4, 94.7) | 4004 | 378 | 94.4 (85.5, 103.9) |

Cumulative Incidence reported per 1000 population.

Abbreviations: SEP, socioeconomic position; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4 shows the adjusted, race-specific associations between each SEP indicator and incident T2DM. The odds of developing T2DM were higher for AAs with low CSEP compared to those with high CSEP [aOR: 1.61, 95% CI (1.05, 2.46)] (Model 1). After both CSEP and ASEP were included simultaneously (Model 2), the CSEP association was attenuated and no longer statistically significant among AA participants, and was similar after additional adjustment for T2DM risk factors. Lower ASEP was independently associated with T2DM in both racial groups, in both separate (Model 1) and simultaneous (Model 2) models adjusted for demographic characteristics. Further adjustment for T2DM risk factors attenuated the ASEP-T2DM associations in both racial groups, but remained statistically significant (Model 3). No significant interactions were observed between CSEP and sex (AA, p=0.051; white, p=0.47) or between ASEP and sex (AA, p=0.82; white, p=0.57). Participants in both racial groups with low CumSEP had higher odds of developing T2DM compared to those with high CumSEP, and these race-specific associations persisted after further adjustment for T2DM risk factors (Model 3). We did not observe an interaction between CumSEP and sex (AA, p=0.72; white, p=0.60).

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations between Lifecourse Socioeconomic Position Indicators and Incident Type 2 Diabetes, by Race—the REGARDS Study, 2003–16

| AFRICAN AMERICAN | WHITE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Model 1 aOR (95% CI) | Model 2 aOR (95% CI) | Model 3 aOR (95% CI) | Model 1 aOR (95% CI) | Model 2 aOR (95% CI) | Model 3 aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| Childhood SEP | ||||||

| Low | 1.61 (1.05, 2.46) * | 1.44 (0.93, 2.23) | 1.47 (0.93, 2.33) | 1.06 (0.74, 1.51) | 0.89 (0.62, 1.28) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.16) |

| Medium | 1.25 (0.82, 1.91) | 1.16 (0.76, 1.78) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.78) | 1.29 (1.02, 1.63) * | 1.16 (0.92, 1.47) | 1.09 (0.86, 1.40) |

| High | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Adult SEP | ||||||

| Low | 2.44 (1.37, 4.36) * | 2.20 (1.22, 3.98) * | 1.63 (0.87, 3.04) | 2.53 (1.78, 3.61) *** | 2.51 (1.74, 3.61) *** | 1.96 (1.33, 2.87) ** |

| Medium | 2.09 (1.25, 3.51) * | 2.01 (1.20, 3.38) * | 1.89 (1.11, 3.24) * | 1.58 (1.21, 2.06) * | 1.56 (1.19, 2.04) * | 1.36 (1.02, 1.80) * |

| High | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Cumulative SEP | ||||||

| Low | 1.92 (1.23, 3.00) ** | 1.65 (1.04, 2.63) * | 1.78 (1.35, 2.35) *** | 1.40 (1.05, 1.87) * | ||

| Medium | 1.35 (0.84, 2.17) | ---- | 1.22 (0.74, 1.99) | 1.20 (0.93, 1.55) | ---- | 1.05 (0.80, 1.37) |

| High | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 ((referent) | ||

| Social Mobility | ||||||

| Stable low | 1.39 (0.85, 2.27) | 1.08 (0.64, 1.81) | 1.36 (0.78, 2.39) | 1.09 (0.61, 1.93) | ||

| Upwardly mobile | 1.54 (1.08, 2.20) * | ---- | 1.62 (1.12, 2.36) * | 0.89 (0.60, 1.32) | ----- | 0.81 (0.54, 1.21) |

| Downwardly mobile | 1.66 (1.00, 2.77) * | 1.34 (0.79, 2.30) | 1.94 (1.41, 2.68) ** | 1.62 (1.16, 2.27) ** | ||

| Stable high | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

Abbreviations: SEP, socioeconomic position; T2DM, type 2 diabetes; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Model 1 = Each SEP indicator controlled for age, sex, % of life lived in the Stroke Belt;

Model 2 = Childhood SEP + Adult SEP + age, sex + % of life lived in the Stroke Belt;

Model 3 = Previous model + T2DM risk factors (BMI, waist circumference, CRP, physical activity, Mediterranean Diet score, smoking status, alcohol consumption).

p <0.05

p <0.01

p <0.001.

In both groups, participants with stable low SEP did not have significantly higher odds of developing T2DM than their counterparts with stable high SEP. Upward mobility was associated with increased odds of developing T2DM for AA participantsin a model adjusted for demographics [aOR=1.54, 95% CI (1.08, 2.20)] and after adjustment for T2DM risk factors [a)R =1.62, 95% CI (1.12, 2.36)]. Downward mobility was associated with increased odds of developing T2DM in both racial groups, but this association was attenuated after further adjustment for T2DM risk factors, persisting among white individuals [aOR=1.94, 95% (1.41, 2.68)], but not AAs [aOR = 1.34, 95% CI (0.79, 2.30)]. Interaction between social mobility and sex (AA, p=0.45; white, p=0.33) was not observed.

Results from the sensitivity analyses were consistent across all SEP measures and reported in Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort study, we found the association between SEP and incident T2DM differed by lifecourse SEP measure used and race group. We found that the association between low SEP in childhood and T2DM observed among AAs was not independent of SEP in adulthood; however, low SEP in adulthood was independently associated with higher odds of T2DM in both racial groups. The association between low CumSEP and T2DM was driven by the combination of low CSEP and ASEP among AA participants but only by low ASEP among white participants. Finally, we found that stable SEP was not associated with T2DM, whereas change in SEP was associated with increased odds of T2DM. Downward mobility increased odds of T2DM for white participants, while upward mobility increased odds of T2DM for AA participants.

Our result for the association between childhood disadvantage and T2DM was consistent in studies including AA participants,[13, 18] but contrasts with other previous studies supporting the critical/sensitive period hypothesis in T2DM.[16, 17, 19] However, while the findings do not confirm the contribution of low CSEP for AAs the magnitude fo the odds ratios suggest that the association may be mediated through low ASEP as reported in earlier prospective studies.[16, 17, 21, 22] Even if early life social circumstances do not have a direct effect on adult health, they may establish trajectories for ASEP which, in turn, influence specific health risks in later life.[3, 32] In the present cohort, when compared to white participants, AAs were more frequently exposed to low SEP in childhood and adulthood, and had higher levels of T2DM risk factors, suggesting that the pathways to developing T2DM for AAs may be through the potential of childhood disadvantage to shape later-life experiences.[5, 32–34]

Our finding that CumSEP was associated with higher T2DM risk and was explained primarily by low ASEP agrees with several earlier reports.[14, 15, 17, 21, 22] The magnitudes of the associations suggest that, regardless of racial group, the effect of early life disadvantage may be magnified by disadvantage during periods beyond early life.[3, 33, 34]

The association of social mobility with the development of T2DM is consistent with reports from other prospective studies;[13, 14, 17, 21, 22] we found that the association between downward mobility and incident T2DM was independent of T2DM risk factors in adulthood among white participants but not among AAs. This observed contrast may reflect the known racial/ethnic differences in the SEP patterning of T2DM risk factors among US adults.[35, 36] Risk factors for T2DM and low SEP in adulthood were significantly more common in AA than in white participants. The finding that AAs who experienced upward social mobility had increased odds of T2DM was consistent with results seen among women previously [13], although our study observed this association for both women and men. Meanwhile, the odds of T2DM for white participants with upward social mobility was similar to that of those with stable high SEP, which was consistent with other prior work.[22]

This paradox of increased risk of T2DM despite improvements in SEP trajectory among AA participants is further evidence of how the gains typically expected due to improvements in social status are not experienced evenly across racial groups.[37, 38] Black Americans in the middle class experience additional exposure to stressors, including but not limited to higher levels of discrimination at work and/or home, and fewer returns on additional education in terms of income and wealth compared to their white counterparts.[37, 38] Furthermore, residential segregation undermines benefits associated with home ownership and increases exposures to additional stressors.[37, 38] Other research has shown that striving to attain success may itself be a chronic stressor which can induce dysregulation of multiple physiological systems and psychological distress over time.[39–41] Specifically, at every age, AAs have higher levels of allostatic load and psychological distress than their white counterparts.[42, 43] Recent studies indicate that the combination of low socioeconomic status in youth and adoption of high-effort coping styles (e.g.,’John Henryism’) to achieve success may be detrimental to cardiometabolic health in young adulthood.[44, 45] The studies cited above suggest plausible mechanisms for the upward social mobility-DM association observed among AA participants.

This study has several potential limitations. First, we lacked repeat measures of SEP and risk factors, which limited our ability to track SEP trajectories in relation to changes in T2DM risk over time. In addition, different SEP indicators may have differing levels of importance over the lifecourse and within different groups.[46, 47] Although the construction of the SEP measures was somewhat limited by unavailability of occupational data, immigration status and measures of structural factors, this is one of few studies on the relationship between SEP and incident T2DM to also include measures of material assets/income in the calculation of SEP. Second, study participants provided retrospective information on parental social circumstances, which may be subject to recall bias, although some evidence suggests that adult recall of childhood SEP is accurate and not differentially affected by adult SEP.[48] Furthermore, survival bias is a concern as this analysis excluded those participants who died or were lost to follow-up before the second in-home visit. Excluded participants were quite similar to included participants in terms of demographics, T2DM risk factors and most SEP measures (Supplemental Table 2); however, the impact of these losses on the results observed in our main or sensitivity analyses is unclear as we do not have outcome data on this group. Third, as CSEP may influence ASEP, our estimates of the direct effects of CSEP and total effects of ASEP may both be biased by unobserved common causes of ASEP.[49] Nonetheless, the current study exhibits several strengths. We used a large, national cohort and a prospective design that allowed for estimating the direction of associations between lifecourse SEP and DM incidence. Secondly, the race-stratified analysis provides new knowledge about the risk of developing T2DM among AA men and women.

Our results supported the accumulation of risk and social mobility hypotheses, and that adulthood was a critical/sensitive period in both racial groups. We did not confirm the critical period hypothesis for low childhood SEP on T2DM incidence, although the magnitude of the association was suggestive for AAs. Our finding that upward social mobility was associated with higher odds of developing T2DM for AAs but not for white Americans extends prior work done in more homogeneous study populations. In summary, low SEP was associated with incident T2DM, although the associations were generally weaker for childhood SEP and less consistent for social mobility among AA and white participants.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We compared three lifecourse hypotheses as it relates to socioeconomic position and incident type 2 diabetes by race.

Childhood socioeconomic position may shape later-life health risks, especially for African American participants.

Cumulative exposure to low socioeconomic position was associated with increased odds of type 2 diabetes in both groups.

Upward mobility was associated with increased odds of type 2 diabetes among African American participants only.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The REGARDS research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official vews of the NINDS or the NIA. Additional support for the childhood ancillary study was provided by R01 AG039588. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Footnotes

CRediT author statement:

Martin: Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation

Beckles: Writing – Original Draft, Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing

Wu: Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing,

McClure: Formal analysis, Software, Data curation, Writing – Review & Editing

Carson: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision

Bennett: Data curation, Writing – Review & Editing

Bullard: Writing – Review & Editing

Glymour: Funding acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing

Unverzagt: Writing – Review & Editing

Cunningham: Funding acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing

Imperatore: Writing – Review & Editing

Howard: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the NINDS, NIA, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Dr. Carson, Ms. Bennett and Dr. Howard report grants from NIH during the conduct of the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, et al. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):804–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Power C, Hertzman C. Social and biological pathways linking early life and adult disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(1):210–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craemer T, Smith T, Harrison B, et al. Wealth Implications of Slavery and Racial Discrimination for African American Descendants of the Enslaved. The Review of Black Political Economy. 2020;47(3):218–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.White TK. Initial conditions at Emancipation: The long-run effect on black–white wealth and earnings inequality. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 2007;31(10):3370–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massey DS. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. American Journal of Sociology. 1990;96(2):329–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roscigno VJ, Karafin DL, Tester G. The Complexities and Processes of Racial Housing Discrimination. Social Problems. 2014;56(1):49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon D, Maxwell C, Castro A. Systematic Inequality and Economic Opportunity: Center for American Progress; 2019. [Available from: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472910/systematic-inequality-economic-opportunity/.

- 11.Walters PB. Educational Access and the State: Historical Continuities and Discontinuities in Racial Inequality in American Education. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhutta N, Chang AC, Dettling LJ, et al. “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances” Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; 2020. [September 28, 2020:[Available from: 10.17016/2380-7172.2797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckles GL, McKeever Bullard K, Saydah S, et al. Life Course Socioeconomic Position, Allostatic Load, and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes among African American Adults: The Jackson Heart Study, 2000–04 to 2012. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(1):39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camelo LV, Giatti L, Duncan BB, et al. Gender differences in cumulative life-course socioeconomic position and social mobility in relation to new onset diabetes in adults-the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(12):858–64.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cirera L, Huerta JM, Chirlaque MD, et al. Life-course social position, obesity and diabetes risk in the EPIC-Spain Cohort. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(3):439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demakakos P, Marmot M, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic position and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: the ELSA study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(5):367–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lidfeldt J, Li TY, Hu FB, et al. A prospective study of childhood and adult socioeconomic status and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maty SC, James SA, Kaplan GA. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of diabetes mellitus among blacks and whites: the Alameda County Study, 1965–1999. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maty SC, Lynch JW, Raghunathan TE, et al. Childhood socioeconomic position, gender, adult body mass index, and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus over 34 years in the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1486–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pikhartova J, Blane D, Netuveli G. The role of childhood social position in adult type 2 diabetes: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith BT, Lynch JW, Fox CS, et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(4):438–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stringhini S, Batty GD, Bovet P, et al. Association of lifecourse socioeconomic status with chronic inflammation and type 2 diabetes risk: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013;10(7):e1001479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsenkova V, Pudrovska T, Karlamangla A. Childhood socioeconomic disadvantage and prediabetes and diabetes in later life: a study of biopsychosocial pathways. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(8):622–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derks IP, Koster A, Schram MT, et al. The association of early life socioeconomic conditions with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: results from the Maastricht study. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard VJ, Woolson RF, Egan BM, et al. Prevalence of hypertension by duration and age at exposure to the stroke belt. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4(1):32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker LE, Kirtland KA, Gregg EW, et al. Geographic distribution of diagnosed diabetes in the U.S.: a diabetes belt. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(4):434–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, et al. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):778–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown DC, Hummer RA, Hayward MD. The Importance of Spousal Education for the Self-Rated Health of Married Adults in the United States. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2014;33(1):127–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kastorini CM, Panagiotakos DB. Mediterranean diet and diabetes prevention: Myth or fact? World J Diabetes. 2010;1(3):65–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray MS, Wang HE, Martin KD, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean-style diet and risk of sepsis in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. Br J Nutr. 2018;120(12):1415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner RJ, Thomas CS, Brown TH. Childhood adversity and adult health: Evaluating intervening mechanisms. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:114–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pudrovska T, Anikputa B. Early-life socioeconomic status and mortality in later life: an integration of four life-course mechanisms. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(3):451–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang YC, Gerken K, Schorpp K, et al. Early-Life Socioeconomic Status and Adult Physiological Functioning: A Life Course Examination of Biosocial Mechanisms. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2017;63(2):87–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, et al. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):617–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, et al. Socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, and inflammation in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2007;116(21):2383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson PB, Williams DR. The Intersection of Race, Gender, and SES: Health Paradoxes. Gender, race, class, & health: Intersectional approaches. Hoboken, NJ, US: Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2006. p. 131–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, et al. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McEwen BS. Allostasis and the Epigenetics of Brain and Body Health Over the Life Course: The Brain on Stress. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):551–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sellers SL, Neighbors HW, Zhang R, et al. The impact of goal-striving stress on physical health of white Americans, African Americans, and Caribbean blacks. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(1):21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simandan D Rethinking the health consequences of social class and social mobility. Soc Sci Med. 2018;200:258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, et al. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brody GH, Yu T, Miller GE, et al. John Henryism Coping and Metabolic Syndrome Among Young Black Adults. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(2):216–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wickrama KA, O’Neal CW, Lee TK. The Health Impact of Upward Mobility: Does Socioeconomic Attainment Make Youth More Vulnerable to Stressful Circumstances? J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(2):271–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krieger N, Okamoto A, Selby JV. Adult female twins’ recall of childhood social class and father’s education: a validation study for public health research. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):704–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.VanderWeele TJ. Mediation Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.