Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, is a potent activator of macrophages. Besides inducing many transcriptional pathways, LPS also elicits rapid morphological changes such as cell spreading. Here we have investigated the signaling pathway that controls macrophage β2-integrin-dependent spreading in response to LPS. We show that inhibition of the adapter protein MyD88, the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase Irak, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, or the Ras-like GTPase Rap1 blocks LPS-induced spreading. In addition, Irak activates p38 and stimulates p38-dependent spreading. The activation of p38 by Irak requires Irak's kinase activity. We find that p38 controls spreading independently of its role in transcription but rather through activation of Rap1. Together, our results suggest that β2-integrin-dependent spreading of macrophages in response to LPS is controlled by a linear signaling pathway via MyD88, Irak, p38, and Rap1.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or endotoxin, the major constituent of the plasma membrane of gram-negative bacteria, is a strong activator of innate immune responses and one of the main causative substances in the development of septic shock (45, 52, 58). LPS is recognized by most cell types, but its effects are mainly mediated by cells of the immune and inflammatory system, including phagocytes and endothelial cells. Several receptors for LPS that are expressed on the surface of phagocytes have been described, including the glycerophosphatidylinositol-linked protein CD14, β2-integrins, and the macrophage scavenger receptor (14). The scavenger receptor does not seem to function as a signaling receptor for LPS, and although β2-integrins may participate in signaling, there is strong evidence that CD14 is the main mediator of LPS effects (15, 23–25, 27, 28).

In phagocytes, LPS induces many functional as well as morphological alterations. These include the stimulation of transcription via NF-κB, the Jnk and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades, stimulation of nitric oxide (NO) production, activation of phagocytosis via the complement receptor (αMβ2, CR3), and stimulation of cell adhesion and spreading (13, 44, 56). The best-understood signaling pathway induced by LPS is the activation of transcription via NF-κB and MAP kinases. LPS signaling is initiated by the binding of LPS to the plasma protein LBP (LPS-binding protein) which delivers LPS to CD14 (58). CD14 lacks a cytoplasmic domain, and it has recently been suggested that LPS signals are transduced through members of the Toll receptor family (10, 26, 32, 42, 49, 50, 62). Toll was first identified in Drosophila, where it is a key player in the response to fungal infection in adult flies (37). In mammals, several Toll-like receptors have been identified and there is accumulating evidence that TLR4 (hToll) mediates LPS-induced signaling (10, 26, 34, 42, 49, 50). Toll proteins possess a cytoplasmic domain similar to the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor and control NF-κB and MAP kinase activation via a pathway that overlaps in part with that used by the IL-1 receptor (34, 48). This pathway includes the death domain, containing adapter protein MyD88 and the IL-1 receptor-associated Ser/Thr kinase (Irak) (4, 29, 31, 43, 46, 55, 61). In IL-1 signaling MyD88 recruits Irak to the receptor complex in a signal-dependent way (61). Upon recruitment Irak is phosphorylated and then leaves the receptor complex to interact with Traf6 (5). Traf6 is the only downstream target of Irak identified so far, and it mediates IL-1-induced activation of NF-κB, Jnk, and p38 (3, 5). In LPS-Toll signaling, Traf6 is also required for NF-κB induction; however, it does not seem to mediate Jnk activation (43, 46, 63). Whether Traf6 is involved in LPS-Toll-induced p38 activation is not known. Interestingly, several reports have suggested that the kinase activity of Irak is not necessary for activating NF-κB and Jnk (33, 38, 41, 60).

One of the earliest cellular responses to LPS in macrophages is cell spreading, but the signaling pathways involved are poorly defined (22). The β2-integrin family, comprising αLβ2, αMβ2, αXβ2, and αDβ2, plays a pivotal role in mediating adhesion and spreading of leukocytes in response to a variety of stimuli, including bacterial products, cytokines, and chemokines (17). These stimuli activate β2-integrins through a process called “inside-out” signaling, which might involve integrin clustering, increases in integrin affinity, changes in the number of integrins expressed at the cell surface, or cytoskeletal reorganization.

In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which LPS induces β2-integrin-dependent spreading of the mouse macrophage cell line J774.A1. We find that spreading is controlled by a linear signaling pathway via MyD88, Irak, p38, and the Rap1 GTPase. The activation of p38 requires Irak's kinase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

LPS from Escherichia coli strain 055:B5 was obtained from Sigma. SB202190 was from Calbiochem. TcdB-1470 was a gift from C. von Eichel-Streiber (Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Mainz, Germany). Polyclonal antibodies to p38 and to dually phosphorylated p38 (Thr180, Tyr182) were purchased from Santa Cruz and New England Biolabs, respectively. The anti-myc-tag antibody (9E10) was a gift from S. Moss (University College London). Monoclonal antibodies to mouse α4, mouse β2, mouse αM, mouse α5, mouse β3, and mouse αv integrins were from Pharmingen, and antibodies to mouse α5β1 and human αvβ5 (cross-reacting with mouse αvβ5) were purchased from Chemicon. Anti-Rap1 antibody was from Transduction Laboratories, anti-AU1 antibody was from Babco, and anti-HA antibody was from Boehringer Mannheim. Fluorescently and horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch and Pierce. AMCA-streptavidin and biotin-, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-, and Texas red-dextran were from Molecular Probes. Rhodamine-phalloidin was purchased from Sigma.

cDNA constructs.

The pRK5myc expression vector has been previously described (35). pRK5myc::Irak (pAS310) encoding human Irak was constructed by PCR using pcDNA3::Irak as the template (V. Goeddel, Tularik, San Francisco, Calif.). pRK5myc::IrakN (pAS311) is a deletion variant of pAS310, encoding the N-terminal 239 amino acids of human Irak, and was made by PCR with pcDNA3::Irak as the template.

pRK5myc::IrakD358N (pAS323) encodes the Irak kinase-dead protein in which aspartate 358 is replaced by an asparagine residue. pAS323 was reconstituted from two PCR fragments generated with primers 5′-GACACCCAAGCTTGGAAACTTTGGCCTGGCCCGGTTCAGC-3′ and 5′-AGTCTCCAAGCTTGGGTGTCAGCCTCTCATCCAG-3′, each in combination with a flanking primer and with pAS310 as the template. A silent nucleotide substitution that created a HindIII site is indicated in bold, and the point mutations that created the kinase-dead mutation are underlined. pRK5myc::MKK6∗ (pAS328), which encodes a constitutively active human MKK6 protein with serine 207 and threonine 211 replaced by glutamate residues, was made by PCR with pcDNA3::Flag-MKK6(Glu) as the template (R. Davis, University of Massachusetts Medical School). PCRs were done using Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). Constructs were verified by sequencing.

pRK5myc::N17Rap1 containing a dominant-negative allele of Rap1, pGEX-2T::RalGDS-RBD expressing the Rap1-binding domain of Ral GDS fused to Gst, and pRK5myc::N43R-Ras encoding dominant-negative R-Ras were provided by A. Self (University College London). pMT2-HA-RalA (N28) encoding N28RalA was provided by Johannes Bos (University of Utrecht). pcDL-SRα-HA::p38αAGF contains dominant-negative p38 and was provided by E. Nishida (Kyoto University). pcDNA3::HA-p38α contains the human p38α gene (H. Nishitoh, Cancer Institute, Tokyo, Japan). pcDNA3::AU1-MyD88▵ encodes dominant-negative MyD88, which lacks amino acids 1 to 152, and was provided by M. Muzio (Mario Negri Institute, Milan, Italy).

J774.A1 cell culture and microinjection.

J774.A1 macrophages were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HIFCS) (Sigma) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (PEN-STR) at 37°C. Cells for microinjection were plated overnight onto acid-washed glass coverslips (13 mm) in four-well plates at a density of 105 cells/ml per well. FITC- or Texas red-dextran or eukaryotic expression vectors (0.1 μg/μl, unless stated otherwise), together with biotin-dextran, were injected into the nucleus of 50 to 100 cells over a period of 15 min. Cells were returned to the incubator for 2 to 5 h for optimal expression.

J774.A1 spreading assay.

To assay spreading of macrophages in response to LPS, cells were plated overnight onto acid-washed glass coverslips (13 mm) in DMEM, 10% HIFCS, and 1% PEN-STR in four-well plates at a density of 105 cells/ml per well. Cells were then incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min unless stated otherwise, fixed, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (see below). Drugs or blocking antibodies were added prior to LPS addition at the indicated concentrations and for the indicated length of time. On average, 200 cells were counted per coverslip and the percentage of spread cells was calculated.

To assay spreading of macrophages expressing cDNAs, cells were microinjected as described above, then treated or not treated with inhibitors or LPS at the indicated concentrations and for the indicated length of time, fixed, and stained for expression of proteins using anti-myc, anti-HA, or anti-AU1 antibodies before staining with rhodamine-phalloidin (see below). Spreading was assessed in the retrieved cells expressing cDNAs.

All experiments were repeated at least three times and the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations. Representative pictures of cells are shown below.

Immunofluorescence staining protocols.

Microinjected and LPS- and/or drug-treated J774.A1 cells on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100–PBS for 5 min, incubated with NH4Cl in PBS (2.7 mg/ml) for 10 min to remove free aldehyde groups, and then stained as previously described (47). Coverslips were rinsed in PBS between each step of the staining procedure. Primary antibodies were diluted in PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 1 μg of human immunoglobulin G (IgG)/ml and left on the coverslip for 45 min. After washing, the coverslips were incubated for 45 min with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies and AMCA-coupled streptavidine (to retrieve biotin-dextran-injected cells) diluted in PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 1 μg of human IgG/ml. For spreading assays, cells were further incubated with rhodamine-phalloidin (200 ng/ml) for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted on moviol mountant containing p-phenylenediamine as an antibleaching agent. After 1 h at room temperature, the coverslips were examined and the cells were counted on a Zeiss axiophot microscope using Zeiss 63×1.4 oil-immersion objectives. Pictures were taken with a Hamamatsu C5985-10 video camera.

Transfection of COS-1 cells.

COS-1 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS and 1% PEN-STR. Cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 2 ml of medium, incubated overnight, and transfected using Lipofectamine (Gibco-BRL), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1 μg of DNA was used for each transfection. After transfection the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The medium was replaced with 2 ml of DMEM–10% FCS–1% PEN-STR, and the cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and then harvested.

Preparation of cell extracts for phospho-p38 analysis, SDS-PAGE, and Western analysis.

Extracts from J774.A1 or transfected COS-1 cells were prepared as follows. J774.A1 cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 2 ml of DMEM–10% HIFCS–1% PEN-STR and incubated overnight at 37°C before treatment with inhibitors and LPS. COS-1 cells were transfected as described above. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then incubated with 250 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 12 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 20 μg of aprotinin/ml, 20 μg of leupeptin/ml) for 20 min on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Samples were denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western analysis were performed by standard methods. Thirty micrograms of protein extract was loaded in each lane.

Purification of RalGDS-RBD.

pGEX-2T::RalGDS-RBD was transformed into E. coli strain BL21. Protein production was initiated by adding IPTG to the culture. The bacteria were lysed by sonication and fusion protein was affinity purified on glutathione-beads by standard methods.

Rap1 activation assay using RalGDS-RBD.

Rap1 pull-down assays were performed as described (16). J774.A1 cells were seeded in 15-cm-diameter dishes at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells per dish in 20 ml of DMEM–10% HIFCS–1% PEN-STR and grown for 64 h at 37°C before treatment with inhibitors and LPS. Cells were washed twice in cold TBS buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl) and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 20 μg of aprotinin/ml, 20 μg of leupeptin/ml). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C. Twenty micrograms of Gst-RalGDS-RBD coupled to glutathione beads was added to each supernatant, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 45 min on a rotating wheel. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer containing 200 mM NaCl. Samples were denatured for 5 min at 95°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using the anti-Rap1 antibody.

RESULTS

LPS induces spreading of J774.A1 macrophages.

To investigate the effect of LPS on the morphology of the mouse macrophage cell line J774.A1, cells were grown on glass coverslips in the presence of 10% serum and then treated or not treated with LPS (1 μg/ml). Within 10 min of LPS addition, between 60 and 70% of the macrophages had changed their morphology from round to flat and spread, as seen by visualization of the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1 and 2A). Less than 15% of the non-LPS-treated cells exhibited the spreading form. Thus, LPS induces spreading of J774.A1 macrophages.

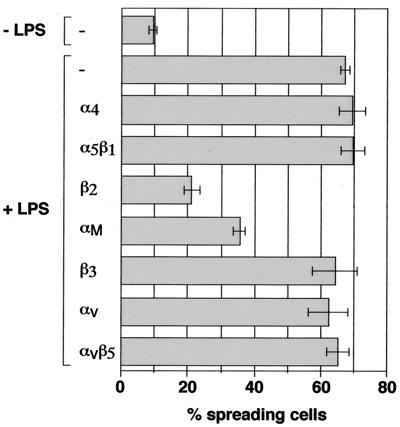

FIG. 1.

Antibodies against β2- and αM-integrins block LPS-induced spreading of J774.A1 macrophages. Macrophages were treated or not treated with blocking antibodies against α4, α5β1, β2, αM, β3, αv, or αvβ5 integrins at a final concentration of 15 μg/ml in the presence of 50 μg of human IgGs for 30 min at 37°C and then were incubated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and the percentage of spreading cells was determined.

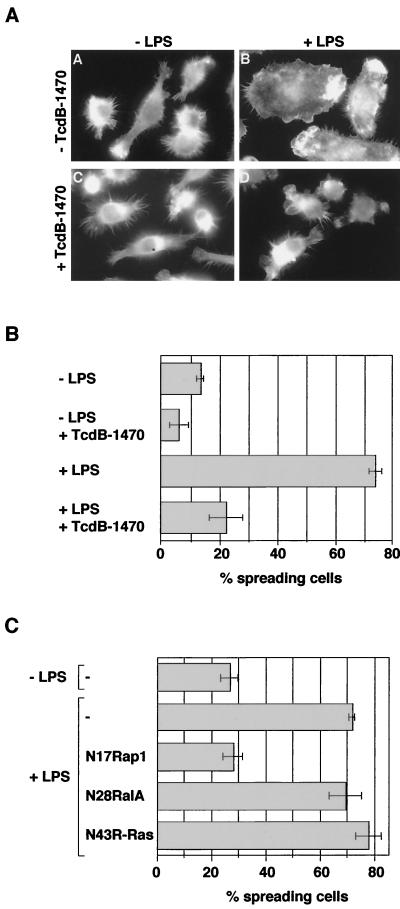

FIG. 2.

Rap1 is required for LPS-induced spreading of J774.A1 macrophages. (A and B) TcdB-1470 inhibits LPS-induced spreading of macrophages. Macrophages were treated with or without TcdB-1470 (10 pg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C and then incubated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and the percentage of spread cells was determined. (C) Expression of dominant-negative Rap1 prevents LPS-induced spreading. Macrophages were microinjected with FITC-dextran or with cDNA constructs encoding myc-tagged N17Rap1 (0.25 μg/μl), myc-tagged N43R-Ras, or HA-tagged N28RalA, returned to the incubator for expression of the constructs, and then treated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Cells were fixed, stained with anti-myc and anti-HA antibody, respectively, and rhodamine-phalloidin, and the percentage of injected or expressing spreading cells was determined. The background of spread cells is usually around 10% higher when cells were microinjected (compare −LPS controls in panels B and C).

LPS-induced spreading is mediated by β2-integrins.

Because LPS-induced spreading is studied using macrophages that are seeded on glass coverslips in the presence of serum, the nature of the cell-matrix interaction is not known. To assess whether LPS-induced spreading is mediated by integrins, EDTA, a divalent cation chelator that is known to block integrin function, was added to macrophages prior to LPS treatment. Pretreatment with EDTA completely inhibited LPS-induced spreading (data not shown). Next, we tested blocking antibodies, directed against various integrin α- and β-subunits, for their ability to inhibit LPS-induced spreading. Preincubation with an antibody against the β2-chain almost completely inhibited spreading induced by LPS (Fig. 1). The anti-αM antibody partially blocked LPS-induced spreading, whereas antibodies against α4, α5β1, β3, αv, or αvβ5 had no effect. This suggests that LPS-induced spreading is mediated by β2-integrins, possibly by the αMβ2-integrin. A role for β2-integrins other than αMβ2 cannot be excluded but could not be tested, as suitable blocking antibodies against these α-chains were not available.

The Rap1 GTPase is required for LPS-induced spreading.

Caron et al. have recently shown that the small Ras-like GTPase Rap1 activates αMβ2 (CR3)-mediated phagocytosis. Furthermore, Rap1 is activated by LPS, and is required for LPS-induced αMβ2 (CR3)-mediated phagocytosis (6). These results have indicated that Rap1 activates the αMβ2-integrin. We therefore investigated whether Rap1 is involved in LPS-induced spreading which is also mediated by β2-integrins. For this purpose we made use of TcdB-1470, a cytotoxin from Clostridium difficile which inhibits Ras-like GTPases including Rap1, R-Ras, and RalA, as well as the Rho-GTPase Rac (9). As seen in Fig. 2A and B, pretreatment with TcdB-1470 (10 pg/ml) fully inhibited LPS-induced spreading.

To determine which GTPase is involved in LPS-induced spreading, cDNAs encoding dominant-negative versions of Rap1, R-Ras, RalA, and Rac were injected into macrophages prior to LPS treatment. Cells expressing N17Rap1 did not spread in response to LPS, whereas injection of control DNA, N43R-Ras, N28RalA, or N17Rac did not impair LPS-induced spreading (Fig. 2C and data not shown). This indicates that Rap1 controls β2-mediated spreading in response to LPS.

LPS-induced spreading is dependent on the p38 MAP kinase.

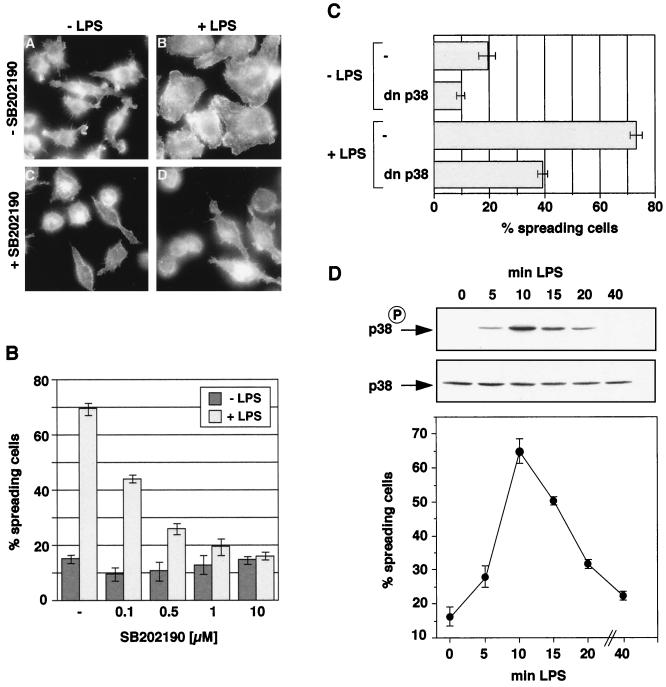

p38 plays an important role in mediating LPS-induced transcription and cytokine production (2, 7, 8, 11, 20, 36, 40), and it also has been implicated in the activation of LPS-induced β2-integrin-dependent adhesion of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to fibrinogen (12). We therefore asked whether activation of p38 is required for LPS-induced spreading of macrophages. J774.A1 cells were pretreated with the p38-specific inhibitor SB202190 and then stimulated with LPS. Pretreatment with SB202190 (0.1 to 10 μM) inhibited macrophage spreading induced by LPS in a dose-dependent way (Fig. 3A and B). A 50% inhibition of spreading was observed at concentrations between 0.1 and 0.5 μM, which is in agreement with the published 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ∼0.3 μM for SB202190. To confirm the involvement of p38 in LPS-induced spreading, a cDNA construct encoding dominant-negative p38 was microinjected into macrophages prior to LPS treatment. Expression of dominant-negative p38 severely decreased the number of spread cells (Fig. 3C). Together these results suggest that p38 is required for LPS-induced spreading.

FIG. 3.

p38 MAP kinase is required for LPS-induced spreading of J774.A1 macrophages. (A and B) SB202190 blocks LPS-induced spreading of macrophages. Macrophages were treated with or without SB202190 (A, 1 μM; B, 0.1 to 10 μM) for 20 min at 37°C, incubated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min, fixed, stained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and then assayed for spreading. (C) Expression of dominant-negative p38 inhibits LPS-induced spreading. Macrophages were microinjected with FITC-dextran (−) or a cDNA construct encoding for HA-tagged dnp38, returned to the incubator for expression of the construct, and then treated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-HA antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin, and the percentage of injected/expressing spread cells was determined. (D) The time course of LPS-induced spreading correlates with the time course of p38 activation. (Top and middle panels) Macrophages were incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times and then lysed. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using anti-p38 (middle) and anti-phospho-p38 (top) antibodies. (Bottom panel) Macrophages were incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times, fixed, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and the percentage of spread cells was determined.

Next, we investigated whether the time course of p38 activation by LPS correlated with the time course of spreading. Macrophages were treated with LPS for various lengths of time and the percentage of spread cells was assessed. Figure 3D shows that LPS stimulates spreading rapidly and transiently. Spread macrophages were seen 5 min after LPS addition; the percentage of spread cells was maximal after 10 min of treatment and declined after 30 to 40 min. We then examined the kinetics of p38 phosphorylation following LPS treatment. Whole cell extracts from cells treated with LPS for various lengths of time were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using an antibody that specifically recognized phosphorylated, i.e., activated, p38 (Fig. 3D). Like spreading, phosphorylated p38 could be detected after 5 min, reached a maximum after 10 min, and declined after 30 to 40 min. The time course for p38 activation was therefore consistent with its participation in LPS-induced spreading.

The above results show that p38 activation and spreading occur within minutes of LPS treatment and that there is no lag phase between the two processes. It is thus unlikely that p38 controls spreading by activating transcription; p38 might have a second function, outside the nucleus and independent of transcription. We therefore wanted to know where activated p38 was localized in LPS-treated cells, and so we performed immunofluorescence on LPS-treated and nontreated cells using the anti-phospho-p38 antibody. In agreement with the biochemical data shown in Fig. 3C, very little activated p38 could be seen in unstimulated cells (see Fig. 5A). In contrast, LPS-treated macrophages contained high levels of activated p38. Interestingly, phosphorylated p38 was found both inside as well as outside the nucleus in LPS-treated cells. Together these data suggest that the role of p38 in LPS-induced spreading is independent of its function in activating transcription.

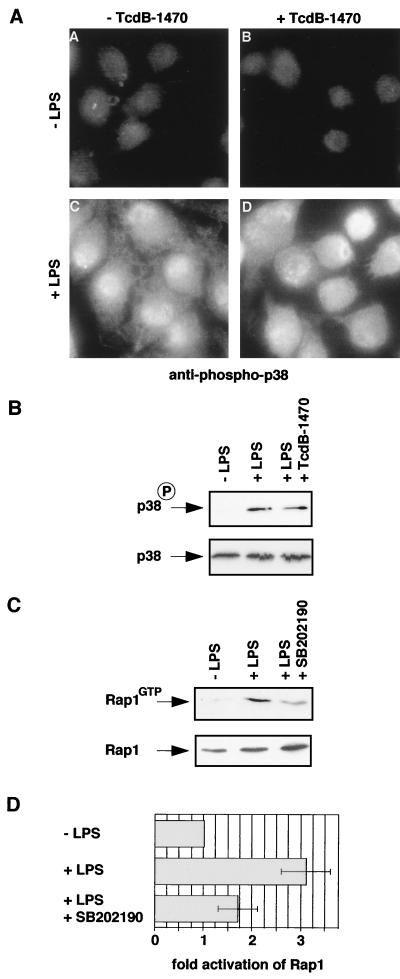

FIG. 5.

Rap1 is downstream of p38. (A and B) TcdB1470 does not inhibit LPS-induced p38 activation in J774.A1 macrophages. Macrophages were treated with or without TcdB-1470 (10 pg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C and then incubated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-phospho-p38 antibody (A), or cells were lysed and whole cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using the anti-phospho-p38 and anti-p38 antibodies (B). (C and D) SB202190 inhibits LPS-induced Rap1 activation in macrophages. Cells were incubated with or without SB202190 (5 μM) for 20 min at 37°C, incubated with or without LPS (0.1 μg/ml) for 15 min, and lysed. Extracts were incubated with 20 μg of Gst-RalGDS-RBD precoupled to gluthathione beads to isolate GTP-bound (activated) Rap1. Levels of activated Rap1 were monitored by Western analysis with anti-Rap1 antibody (upper panel). Levels of Rap1 in total lysates are shown in the lower panel. (D) Western blots of five individual experiments were scanned and quantified. Rap1GTP levels were normalized to total Rap1 levels, and the activation of Rap1 by LPS in the presence or absence of SB202190 was calculated as fold activation of Rap1 compared to non-LPS-treated cells.

Activation of p38 is sufficient to induce spreading of macrophages.

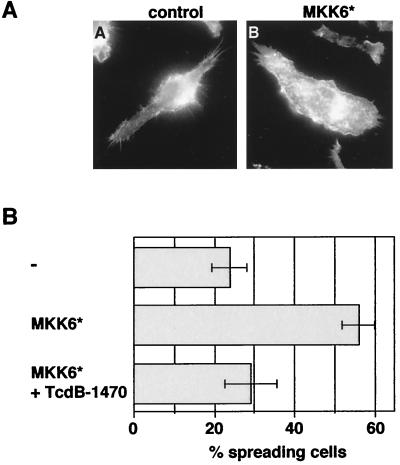

We next wanted to know whether activation of p38 is sufficient to activate spreading. The MAP kinase kinase MKK6 selectively phosphorylates and activates p38 (21). An expression vector encoding a constitutively active, myc-tagged MKK6 (MKK6∗) was microinjected into J774.A1 macrophages. Cells were fixed and stained for phosphorylated p38. MKK6∗-expressing cells showed high levels of phosphorylated p38 compared to control-injected cells, confirming that MKK6 can activate p38 (data not shown). Like LPS, MKK6∗ activated p38 both inside and outside the nucleus (data not shown). We then assayed MKK6∗-injected cells for spreading. As can be seen in Fig. 4A and B, approximately 55% of the cells expressing MKK6∗ were spread compared to only 22% of the control-injected cells. This suggests that activation of p38 is sufficient to induce spreading of macrophages.

FIG. 4.

Activated MKK6 induces Rap1-dependent spreading in J774.A1 macrophages. (A and B) Macrophages were microinjected with FITC dextran (−), or a cDNA construct encoding for myc-tagged activated MKK6 (MKK6∗). Cells were returned to the incubator for expression of the construct, and treated or not treated with TcdB-1470 (10 pg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-myc antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin and the percentage of expressing/injected spread cells was counted.

Rap1 functions downstream of p38.

We next asked whether Rap1 functions upstream or downstream of p38 in controlling macrophage spreading. For this purpose, we analyzed if pretreatment with TcdB-1470 prevents LPS-induced p38 activation as seen by immunofluorescence. Although TcdB-1470 blocked spreading in response to LPS, p38 was still activated (Fig. 5A). TcdB-1470 treatment alone did not activate p38. Also, we prepared protein extracts from cells treated with TcdB-1470 and LPS and subjected them to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis, probing for phosphorylated p38. Consistent with the result obtained by using immunofluorescence, TcdB-1470 did not inhibit LPS-induced p38 activation (Fig. 5B). This suggests that Rap1 is not upstream of p38 in the LPS-spreading pathway. Because p38 activation is sufficient to induce spreading, it is likely that Rap1 is downstream of p38. To gain further evidence for this, we investigated whether TcdB-1470 blocks MKK6∗-induced spreading. Following microinjection of MKK6∗ DNA, cells were treated or not treated with TcdB-1470 and assayed for spreading. Figure 4B shows that the number of MKK6∗-expressing cells which were spread was severely reduced upon treatment with TcdB-1470. Finally, we checked whether activation of Rap1 by LPS was blocked by the p38 inhibitor SB202190. Activation of Rap1 was measured by “pull-down” experiments using the Rap1-binding domain of RalGDS as an activation-specific probe. As described previously, LPS stimulated activation of Rap1 (Fig. 5C and D) (6). However, pretreatment of cells with the p38 inhibitor strongly decreased the activation of Rap1 in response to LPS (Fig. 5C and D). Therefore, Rap1 functions downstream of p38 in the control of spreading.

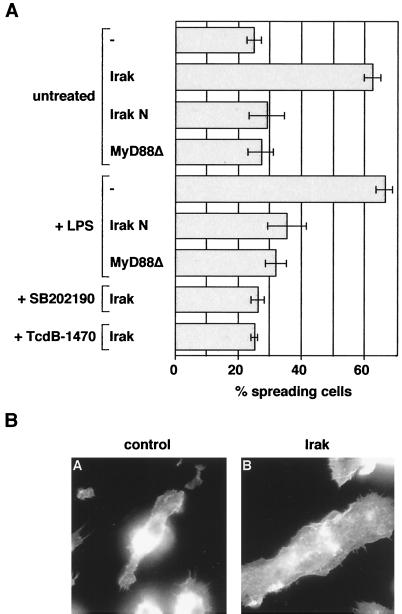

LPS-induced spreading is mediated via MyD88 and Irak.

Irak and MyD88 have been shown to mediate LPS/Toll-induced activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases (31, 43, 46, 55). We therefore wanted to know whether Irak and MyD88 are also required for LPS-induced spreading. For this purpose, Irak and MyD88 deletion constructs (Irak N and MyD88▵, respectively) were made. Such constructs behave as dominant-negative alleles, as shown by their ability to block LPS/TLR4-induced NF-κB activation (43, 46; also data not shown). Irak N and MyD88▵ did not induce significant spreading when microinjected into macrophages (Fig. 6A). When microinjected prior to LPS addition, Irak N and MyD88▵ inhibited the induction of spreading by LPS (Fig. 6A). This suggests that LPS-induced spreading of macrophages is mediated via MyD88 and Irak.

FIG. 6.

(A) LPS-induced spreading requires Irak and MyD88; Irak-induced spreading is dependent on p38 and Rap1. Shown here is the induction of macrophage spreading by Irak and MyD88 constructs in the presence or absence of LPS, SB202190, or TcdB-1470. Macrophages were microinjected with FITC-dextran (−) or cDNAs encoding for myc-tagged Irak wild-type and mutant constructs or AU1-tagged MyD88▵. Cells were returned to the incubator for expression of the constructs and then incubated as indicated either with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 10 min, SB202190 (1 μM) for 20 min, or TcdB-1470 (10 pg/ml) for 2 h. Cells were then fixed, stained with anti-myc or anti-AU1 antibodies and rhodamine-phalloidin, and assayed for spreading. (B) Irak induces spreading in J774.A1 macrophages. Macrophages were microinjected with FITC-dextran (control) or a cDNA construct encoding for myc-tagged Irak. Cells were returned to the incubator for expression of the construct, fixed and stained with anti-myc and rhodamine-phalloidin, and assayed for spreading.

Irak induces p38- and Rap1-dependent spreading.

Next, we asked whether overexpression of Irak was sufficient to induce spreading in macrophages. For this purpose, Irak DNA was microinjected into macrophages and cells were assayed for spreading. Figure 6A and B show that more than 60% of cells expressing Irak were spread compared to control-injected cells.

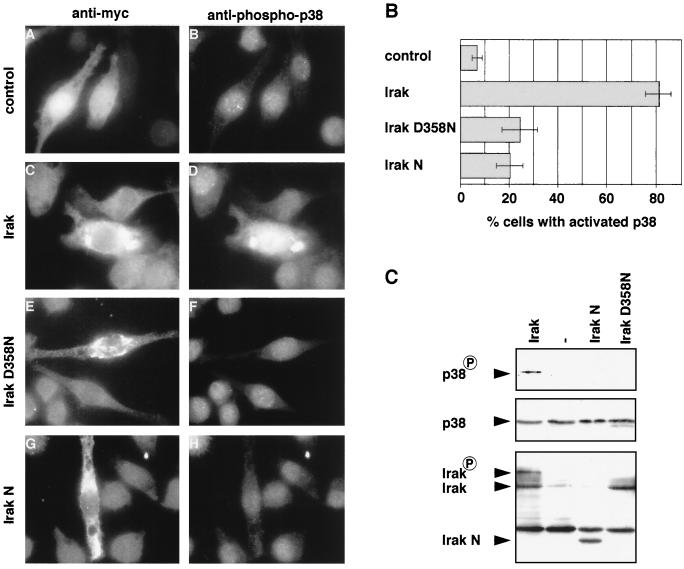

To determine whether Irak was upstream of p38 in mediating spreading, we asked whether Irak could activate p38. Irak DNA was microinjected into macrophages and immunofluorescence was performed using the anti-phospho-p38 antibody. As seen in Fig. 7A and B, unlike control-injected cells, cells expressing Irak showed high levels of phosphorylated p38. Next, we wanted to confirm this result biochemically. Because J774.A1 macrophages cannot be transfected, we transfected COS-1 cells with Irak and control DNA. Cell extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using the anti-phospho-p38 antibody. As shown in Fig. 7C, expression of Irak in COS-1 cells, as in macrophages, stimulated phosphorylation of p38. Next we investigated whether Irak-induced spreading was dependent on p38. Macrophages were microinjected with Irak DNA, treated or not treated with the p38-inhibitor SB202190, and assayed for spreading. Irak-expressing cells that had been treated with SB202190 did not spread (Fig. 6A). These data suggest that Irak is upstream of p38 in mediating LPS-induced spreading. We also tested whether Irak induced spreading via the Rap1 GTPase. Macrophages were microinjected with Irak DNA and treated with TcdB-1470 before the spreading assay. As expected, pretreatment with TcdB-1470 prevented Irak-induced spreading, confirming that Irak is also upstream of Rap1 (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 7.

(A and B) Irak's kinase activity is required for activation of p38 in J774.A1 macrophages. Macrophages were microinjected with Texas red-dextran (control) or cDNAs encoding myc-tagged Irak, Irak D358N, or Irak N. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-myc (C, E, and G) or anti-phospho-p38 (B, D, F, and H) antibodies. The percentage of cells with activated p38 was determined. (C) Irak's kinase activity is required for activation of p38 in COS-1 cells. cDNAs encoding myc-tagged Irak, Irak D358N, or Irak N and control DNA (−) together with cDNA encoding for p38α were transfected into COS-1 cells. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using anti-phospho-p38 (top panel), anti-p38 (middle panel), and anti-myc (bottom panel) antibodies. The band above Irak N, which is visible in all four lanes, is due to cross-reactivity with the secondary antibody.

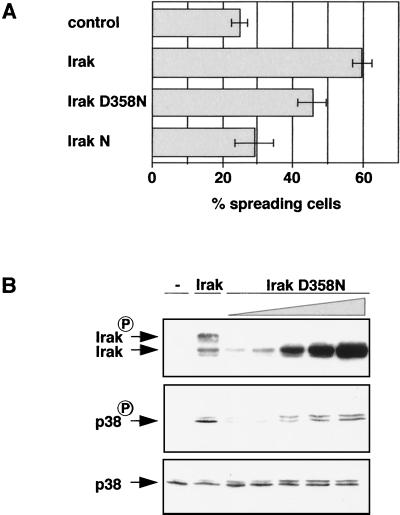

Irak's kinase activity is required for activation of p38.

Several reports have stated that Irak's kinase activity is not needed for the activation of NF-κB and Jnk MAP kinase (33, 38, 41). We therefore wanted to know whether Irak's kinase activity was required for the induction of p38 and spreading. A kinase-dead allele of Irak (Irak D358N) was constructed by introducing a point mutation into the sequence encoding the phosphotransfer site of the kinase motif, changing aspartate 358 to asparagine. Irak D358N was injected into macrophages and cells were stained with the anti-phospho-p38 antibody. In contrast to Irak-expressing cells, very little phosphorylated p38 could be detected in cells expressing Irak D358N (Fig. 7A and B). Phospho-p38 levels were similar to those in cells expressing nonfunctional Irak N or in control-injected cells. To confirm this result biochemically, Irak D358N was transfected into COS-1 cells, extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using the anti-phospho-p38 antibody. Figure 7C shows that in contrast to Irak, Irak D358N did not activate p38 in COS-1 cells, although both proteins were expressed at a comparable level. In addition, whereas the Irak wild-type protein appeared as two bands which presumably correspond to unphosphorylated and autophosphorylated Irak (4, 38, 41), no autophosphorylated form of Irak D358N could be detected, suggesting that Irak D358N indeed is inactive. Therefore, we conclude that Irak's kinase activity is required to activate p38.

Next we examined whether Irak D358N induces spreading of macrophages. Irak D358N was significantly less efficient than wild-type Irak in inducing spreading (Fig. 8A). Since the mutant Irak construct can still dimerize with endogenous, wild-type Irak, it is possible that Irak D358N can induce low levels of p38 activation which might be undetectable in the immunofluorescence assay but sufficient to allow induction of some spreading. To investigate this, we transfected COS-1 cells with increasing amounts of Irak D358N DNA, prepared cell extracts, and subjected them to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis probing for phosphorylated p38 (Fig. 8B). Indeed, when Irak D358N was expressed at very high levels, some activated p38 could be detected.

FIG. 8.

(A) Some residual activity is associated with Irak D358N which is sufficient to induce some spreading of macrophages. Macrophages were microinjected with FITC-dextran (control) or cDNAs encoding myc-tagged Irak, Irak D358N, or Irak N. Cells were then fixed, stained with anti-myc antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin, and assayed for spreading. (B) Overexpression of Irak D358N induces some p38 activation. COS-1 cells were transfected with cDNA encoding for p38α along with control DNA (−), a cDNA construct encoding for myc-tagged Irak, or with increasing amounts of cDNA encoding for myc-tagged Irak D358N. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using anti-phospho-p38 (top panel), anti-p38 (middle panel), and anti-myc (bottom panel) antibodies.

DISCUSSION

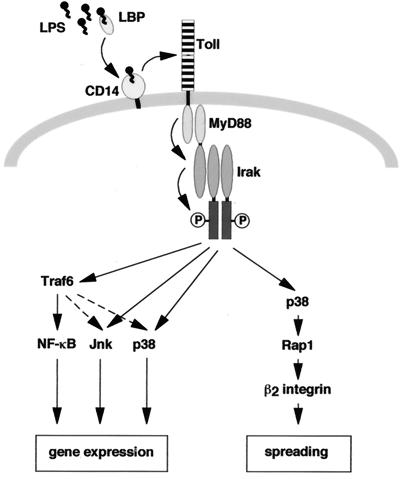

Macrophages respond to LPS by changing their morphology from a round to a spread form (44). Here, we describe several findings concerning the signaling pathway by which LPS stimulates macrophage spreading. First, LPS-induced spreading is inhibited by antibodies against β2-integrins. Second, dominant-negative versions of MyD88, Irak, p38 MAP kinase, or Rap1 block LPS-induced spreading. Third, Irak activates p38 and stimulates p38-dependent spreading. Fourth, the activation of p38 by Irak is dependent on its kinase activity. Fifth, LPS-induced activation of Rap1 requires p38. Together these results suggest that LPS-induced β2-integrin-dependent spreading is mediated by a linear pathway via MyD88, Irak kinase, p38, and Rap1. A model summarizing our data is shown in Fig. 9.

FIG. 9.

Model of LPS-induced signaling pathways leading to activation of transcription and spreading. LPS-induced spreading is mediated by a linear pathway, comprising MyD88, Irak, p38, Rap1, and β2-integrins. See Discussion for further details.

The role of Irak's kinase activity in IL-1 and LPS signaling is unclear at present. The majority of reports have stated that the kinase activity of Irak is not required for the activation of NF-κB and Jnk. Overexpression of an Irak kinase-dead mutant, like overexpression of Irak, leads to activation of NF-κB and Jnk and also restores IL-1 signaling in Irak-deficient cells (33, 38, 41, 60). In contrast, Vig et al. found that overexpression of a kinase-dead mutant of mouse Irak did not activate a NF-κB-dependent reporter gene (59). Furthermore, pelle, the Drosophila homolog of Irak, has been reported to require its kinase activity to rescue pelle null mutants and for the activation of dorsal, the fly NF-κB homolog (18, 54). The role of Irak's kinase activity in inducing p38 MAP kinase has not been investigated. Here we find that an Irak kinase-dead mutant (Irak D358N) is unable to activate p38 MAP kinase in macrophages and COS-1 cells when expressed at levels similar to those of wild-type Irak. This suggests that the kinase activity of Irak is required for the activation of at least some downstream signaling pathways. Although Irak D358N did not induce detectable activation of p38 in macrophages, it still induced some spreading. It is likely that Irak D358N induces some activation of p38 but that the immunofluorescence assay with the phospho-p38 antibody is not sensitive enough to detect small increases. When expressed in COS-1 cells at high levels, Irak D358N is able to induce some p38 activation, and it appears that some catalytic activity is still associated with Irak D358N. This is probably due to its ability to form heterodimers with endogenous wild-type Irak, as shown previously, and such heterodimers might be partially active (60).

What might be downstream of Irak in activating p38? So far the only known downstream target of Irak is Traf6 (5). Traf6 mediates the activation of NF-κB, Jnk, and p38 in response to IL-1 (3, 5) and also is required for the stimulation of NF-κB by LPS/Toll (43, 46, 63). However, in contrast to IL-1 signaling, Traf6 does not mediate the Toll-induced activation of Jnk (46). Our preliminary results show that dominant-negative Traf6 does not block Irak-induced p38 activation in COS-1 cells and reduces LPS-induced spreading of macrophages by only 30%. This relatively small effect suggests that Traf6 is not involved in the activation of p38/spreading by LPS in macrophages (A.S. and A.H., unpublished observations). Thus although the general concept of the IL-1 and LPS/Toll signaling pathways appears to be conserved, individual components of the pathways may differ. It will be interesting to see whether other Irak targets can be identified which mediate the activation of Jnk and p38 in response to LPS/Toll.

The role of p38 MAP kinase in the control of transcription has been studied in detail; however, little is known about functions that p38 can have independently of protein synthesis. Our results suggest that the MAP kinase p38 controls macrophage spreading in response to LPS and that it does so independently of transcription/protein synthesis. First, the p38-specific inhibitor SB202190 or dominant-negative p38 inhibits spreading in response to LPS. Second, activation of p38 by constitutively active MKK6 induces spreading. Third, both p38 activation and spreading occur within minutes of LPS treatment and there is no lag phase between p38 activation and spreading. Fourth, phosphorylated, activated p38 can be found both inside and outside the nucleus following stimulation of macrophages with LPS. In agreement with our findings, Detmers et al. have also reported that p38 is required for the LPS-induced activation of β2 integrin-dependent adhesion of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to fibrinogen and the subsequent oxidative burst and that this does not require protein synthesis (12).

How might p38 control macrophage spreading? The activation of the Ras-like GTPase Rap1 by LPS is inhibited by SB202190, suggesting that p38 controls the GTP loading of Rap1. Hackeng et al. have recently reported that in platelets low-density lipoprotein activates Rap1 and that this is partially dependent on p38 activation and requires the formation of thromboxane A2 (19). Our preliminary results suggest that thromboxane A2 production is not required for macrophage spreading in response to LPS, as the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin does not block LPS-induced spreading (A.S. and A.H., unpublished observations). How might p38 activate Rap1? A simple and attractive possibility would be that p38 directly phosphorylates a Rap1 GDP/GTP exchange factor (GEF) and thereby activates Rap1. Several GEFs for Rap1 have been identified to date, and it remains to be determined whether any of them can be phosphorylated and activated by p38 (64).

Accumulating evidence indicates that the small GTPase Rap1 is involved in the activation of integrin function in response to a variety of stimuli. Caron et al. have shown that Rap1 mediates the activation of phagocytosis via αMβ2-integrin (complement receptor 3) following macrophage stimulation with LPS, phorbol myristate acetate, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and platelet-activating factor (6). Furthermore, SPA-1, a GTPase-activating protein for Rap1, negatively regulates cell adhesion of HeLa cells to fibronectin (57). Rap1 also controls CD31-stimulated T-cell adhesion to ICAM and VCAM via LFA-1 (αLβ2) and VLA-4 (α4β1), respectively (51). Our data show that Rap1 mediates LPS-induced β2-integrin-dependent spreading of macrophages. This suggests that Rap1 is a general activator of integrin function. The mechanism by which Rap1 controls integrin function is not known. Rap1 might regulate integrin clustering, integrin affinity, or integrin interaction with the cytoskeleton. Several effectors for Rap1 have been isolated including several RalGEFs, B-raf, Krit1, and AF6 (39, 53, 64). Whether any of them is involved in the control of integrin activation has yet to be shown.

β2-integrins play a crucial role in mediating leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and the migration into tissues. This is most clearly highlighted by the leukocyte adhesion deficiency disease (LAD), in which leukocytes are deficient in β2-integrin expression and thus are defective in adhesion (1). Patients with LAD suffer from recurrent severe bacterial infections. On the other hand, however, enhanced adhesion of leukocytes as stimulated by LPS during septic shock can lead to vascular and tissue damage and thereby contribute to the development of multiple organ failure (30). In this study we have identified several components of the signaling pathway leading to increased β2-integrin-dependent adhesion and spreading of macrophages in response to LPS. These results may prove important in the development of therapies to fight conditions such as septic shock.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Bos, R. Davis, C. von Eichel-Streiber, D. Goeddel, S. Moss, M. Muzio, E. Nishida, H. Nishitoh, and A. Self for reagents and DNA constructs, and members of the lab for valuable discussion.

A.S. is the recipient of an EMBO long-term fellowship. E.C. is supported by the Wellcome Trust. A.H. thanks the Cancer Research Campaign (UK) for generous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D C, Springer T A. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency: an inherited defect in the Mac-1, LFA-1, and p150,95 glycoproteins. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:175–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldassare J J, Bi Y, Bellone C J. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in IL-1 beta transcription. J Immunol. 1999;162:5367–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baud V, Liu Z G, Bennett B, Suzuki N, Xia Y, Karin M. Signaling by proinflammatory cytokines: oligomerization of TRAF2 and TRAF6 is sufficient for JNK and IKK activation and target gene induction via an amino-terminal effector domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1297–1308. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Z, Henzel W J, Gao X. IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science. 1996;271:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Z, Xiong J, Takeuchi M, Kurama T, Goeddel D V. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caron E, Self A J, Hall A. The small GTPase Rap1 controls functional activation of the macrophage integrin αMβ2 by LPS and other inflammatory mediators. Curr Biol. 2000;10:974–978. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter A B, Knudtson K L, Monick M M, Hunninghake G W. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. The role of TATA-binding protein (TBP) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30858–30863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter A B, Monick M M, Hunninghake G W. Both Erk and p38 kinases are necessary for cytokine gene transcription. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:751–758. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaves-Olarte E, Low P, Freer E, Norlin T, Weidmann M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Thelestam M. A novel cytotoxin from Clostridium difficile serogroup F is a functional hybrid between two other large clostridial cytotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11046–11052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow J C, Young D W, Golenbock D T, Christ W J, Gusovsky F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean J L, Brook M, Clark A R, Saklatvala J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA stability and transcription in lipopolysaccharide-treated human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:264–269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detmers P A, Zhou D, Polizzi E, Thieringer R, Hanlon W A, Vaidya S, Bansal V. Role of stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38) in beta 2-integrin-dependent neutrophil adhesion and the adhesion-dependent oxidative burst. J Immunol. 1998;161:1921–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downey J S, Han J. Cellular activation mechanisms in septic shock. Front Biosci. 1998;3:468–476. doi: 10.2741/a293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenton M J, Golenbock D T. LPS-binding proteins and receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:25–32. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaherty S F, Golenbock D T, Milham F H, Ingalls R R. CD11/CD18 leukocyte integrins: new signaling receptors for bacterial endotoxin. J Surg Res. 1997;73:85–89. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franke B, Akkerman J W, Bos J L. Rapid Ca2+-mediated activation of Rap1 in human platelets. EMBO J. 1997;16:252–259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gahmberg C G, Tolvanen M, Kotovuori P. Leukocyte adhesion—structure and function of human leukocyte beta2-integrins and their cellular ligands. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:215–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosshans J, Schnorrer F, Nusslein-Volhard C. Oligomerisation of Tube and Pelle leads to nuclear localisation of dorsal. Mech Dev. 1999;81:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackeng C M, Franke B, Relou I A, Gorter G, Bos J L, Van Rijn H J, Akkerman J W. Low-density lipoprotein activates the small GTPases Rap1 and Ral in human platelets. Biochem J. 2000;349:231–238. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Jiang Y, Li Z, Kravchenko V V, Ulevitch R J. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature. 1997;386:296–299. doi: 10.1038/386296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han J, Lee J D, Jiang Y, Li Z, Feng L, Ulevitch R J. Characterization of the structure and function of a novel MAP kinase kinase (MKK6) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2886–2891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haslett C, Worthen G S, Giclas P C, Morrison D C, Henson J E, Henson P M. The pulmonary vascular sequestration of neutrophils in endotoxemia is initiated by an effect of endotoxin on the neutrophil in the rabbit. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:9–18. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haworth R, Platt N, Keshav S, Hughes D, Darley E, Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Kodama T, Gordon S. The macrophage scavenger receptor type A is expressed by activated macrophages and protects the host against lethal endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1431–1439. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Lin X Y, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. CD14-deficient mice are exquisitely insensitive to the effects of LPS. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;392:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingalls R R, Arnaout M A, Golenbock D T. Outside-in signaling by lipopolysaccharide through a tailless integrin. J Immunol. 1997;159:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingalls R R, Golenbock D T. CD11c/CD18, a transmembrane signaling receptor for lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1473–1479. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanakaraj P, Ngo K, Wu Y, Angulo A, Ghazal P, Harris C A, Siekierka J J, Peterson P A, Fung-Leung W P. Defective interleukin (IL)-18-mediated natural killer and T helper cell type 1 responses in IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1129–1138. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karima R, Matsumoto S, Higashi H, Matsushima K. The molecular pathogenesis of endotoxic shock and organ failure. Mol Med Today. 1999;5:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirschning C J, Wesche H, Merrill Ayres T, Rothe M. Human toll-like receptor 2 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2091–2097. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knop J, Martin M U. Effects of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) expression on IL-1 signaling are independent of its kinase activity. FEBS Lett. 1999;448:81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kopp E B, Medzhitov R. The Toll-receptor family and control of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamarche N, Tapon N, Stowers L, Burbelo P D, Aspenstrom P, Bridges T, Chant J, Hall A. Rac and Cdc42 induce actin polymerization and G1 cell cycle progression independently of p65PAK and the JNK/SAPK MAP kinase cascade. Cell. 1996;87:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J C, Young P R. Role of CSB/p38/RK stress response kinase in LPS and cytokine signaling mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:152–157. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart J M, Hoffmann J A. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, Commane M, Burns C, Vithalani K, Cao Z, Stark G R. Mutant cells that do not respond to interleukin-1 (IL-1) reveal a novel role for IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4643–4652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linnemann T, Geyer M, Jaitner B K, Block C, Kalbitzer H R, Wittinghofer A, Herrmann C. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of the interaction between the Ras binding domain of AF6 and members of the Ras subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13556–13562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manthey C L, Wang S W, Kinney S D, Yao Z. SB202190, a selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, is a powerful regulator of LPS-induced mRNAs in monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:409–417. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maschera B, Ray K, Burns K, Volpe F. Overexpression of an enzymically inactive interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase activates nuclear factor-kappaB. Biochem J. 1999;339:227–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway C A., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Kopp E, Stadlen A, Chen C, Ghosh S, Janeway C A., Jr MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 1998;2:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morland B, Kaplan G. Macrophage activation in vivo and in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1977;108:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(77)80035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrison D C, Ryan J L. Bacterial endotoxins and host immune responses. Adv Immunol. 1979;28:293–450. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muzio M, Natoli G, Saccani S, Levrero M, Mantovani A. The human toll signaling pathway: divergence of nuclear factor kappaB and JNK/SAPK activation upstream of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) J Exp Med. 1998;187:2097–2101. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nobes C D, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Neill L A, Greene C. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor family: ancient signaling machinery in mammals, insects, and plants. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M Y, Huffel C V, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qureshi S T, Lariviere L, Leveque G, Clermont S, Moore K J, Gros P, Malo D. Endotoxin-tolerant mice have mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) J Exp Med. 1999;189:615–625. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reedquist K A, Ross E, Koop E A, Wolthuis R M, Zwartkruis F J, van Kooyk Y, Salmon M, Buckley C D, Bos J L. The small GTPase, Rap1, mediates CD31-induced integrin adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1151–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schletter J, Heine H, Ulmer A J, Rietschel E T. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin activity. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:383–389. doi: 10.1007/BF02529735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serebriiskii I, Estojak J, Sonoda G, Testa J R, Golemis E A. Association of Krev-1/rap1a with Krit1, a novel ankyrin repeat-containing protein encoded by a gene mapping to 7q21–22. Oncogene. 1997;15:1043–1049. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shelton C A, Wasserman S A. pelle encodes a protein kinase required to establish dorsoventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1993;72:515–525. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90071-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swantek J L, Tsen M F, Cobb M H, Thomas J A. IL-1 receptor-associated kinase modulates host responsiveness to endotoxin. J Immunol. 2000;164:4301–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sweet M J, Hume D A. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsukamoto N, Hattori M, Yang H, Bos J L, Minato N. Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18463–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vig E, Green M, Liu Y, Donner D B, Mukaida N, Goebl M G, Harrington M A. Modulation of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1-dependent NF-kappaB activity by mPLK/IRAK. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13077–13084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wesche H, Gao X, Li X, Kirschning C J, Stark G R, Cao Z. IRAK-M is a novel member of the Pelle/interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19403–19410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wesche H, Henzel W J, Shillinglaw W, Li S, Cao Z. MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity. 1997;7:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang R B, Mark M R, Gray A, Huang A, Xie M H, Zhang M, Goddard A, Wood W I, Gurney A L, Godowski P J. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signalling. Nature. 1998;395:284–288. doi: 10.1038/26239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang F X, Kirschning C J, Mancinelli R, Xu X P, Jin Y, Faure E, Mantovani A, Rothe M, Muzio M, Arditi M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates nuclear factor-kappaB through interleukin-1 signaling mediators in cultured human dermal endothelial cells and mononuclear phagocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7611–7614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zwartkruis F J, Bos J L. Ras and Rap1: two highly related small GTPases with distinct function. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:157–165. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]