Abstract

Periodontitis has been associated with the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis, and previous studies have shown phenotypic differences in the pathogenicities of strains of P. gingivalis. An accurate and comprehensive phylogeny of strains of P. gingivalis would be useful in determining if there is an evolutionary basis to pathogenicity in this species. Previous phylogenies of P. gingivalis strains based on random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) show little agreement. While the 16S ribosomal gene is the standard for phylogenetic reconstruction among bacterial species, it is insufficiently variable for this purpose. In the present study, the phylogeny of P. gingivalis was constructed on the basis of the sequence of the most variable region of the ribosomal operon, the intergenic spacer region (ISR). Heteroduplex analysis of the ISR has been used to study the variability of P. gingivalis strains in periodontitis. In the present study, typing by heteroduplex analysis was compared to ISR sequence-based phylogeny and close agreement was observed. The two strains of P. gingivalis whose heteroduplex types are strongly associated with periodontitis were found to be closely related and were well separated from strains whose heteroduplex types are less strongly associated with disease, suggesting a relationship between pathogenicity and phylogeny.

Periodontitis is a destructive disease that affects a large proportion of the population, resulting in irreversible damage to the attachment of teeth to supporting structures. It has repeatedly been associated with the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis (3, 8, 10). Previous studies have shown phenotypic differences in the pathogenicities of strains of P. gingivalis in animal models (6, 7, 17, 20) and in humans (1, 9). An accurate and comprehensive phylogeny of strains of P. gingivalis would be useful in determining if there is an evolutionary basis to pathogenicity in P. gingivalis. Previous phylogenetic reconstruction of strains of P. gingivalis made with data obtained by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting analysis (16) and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (14) showed little agreement. The standard locus for phylogenetic reconstructions at the species level, the small ribosomal subunit gene, is not sufficiently variable for distinguishing among strains. In this study a phylogeny of P. gingivalis was constructed on the basis of the sequence of the most variable region of the ribosomal operon, the intergenic spacer region (ISR).

Heteroduplex analysis of the ISR has been used to study P. gingivalis strain variability in patients with periodontitis (9). Heteroduplex typing does not resolve all strains, and the agreement between heteroduplex typing and sequence-based phylogeny has not been examined. In this study, ISR heteroduplex typing was compared to ISR sequence-based phylogeny, and the relationship between phylogeny and pathogenicity in humans was examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequencing.

Sequence data for 18 laboratory strains and the amplicons from 19 clinical samples of P. gingivalis were obtained from an ISR sequence database (18). P. gingivalis strain 19A4 was obtained from Denis Mayrand, and the ribosomal ISR was amplified and sequenced as described previously (18). Sequences were assembled in SeqApp (http://IUBIO.BIO.INDIANA.EDU) and were aligned with the ClustalX program (ftp://ftp-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/pub/ClustalX/) for automated alignment and SeqApp for final hand alignment.

Phylogenetic reconstruction.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed with Paup* 4 software (Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.). Distance tree parameters were set so that the objective function was minimum evolution with the Kimura two-parameter correction for multiple hits; missing or ambiguous data were ignored. Parsimony tree parameters were set for accelerated transformations, internal node states were allowed to differ from terminal states, multiple state characters were interpreted as uncertainty, mulpars was in effect, maxtrees was set to 10,000, and gaps were considered to be a fifth state. Each gap was treated as a single event, regardless of length. When performing heuristic parsimony searches, tree bisection and reconnection branch swapping were chosen. Starting trees were chosen by the random stepwise method and were repeated 10 times. A consensus tree was made by using the majority-rule criteria while including other compatible groupings.

Heteroduplex analysis.

Strains 22KN612, B57, DCR2011, ESO/27, HG564, JKG7, and MSM3 were obtained from Christopher Cutler and were typed by heteroduplex analysis as described previously (12). Briefly, heteroduplexes were formed by melting and reannealing a mixture of ISR PCR products from a sample and from a panel of known strains. The formation of heteroduplexes was detected by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

ISR phylogeny.

The phylogenetic relationship between 19 laboratory strains of P. gingivalis was reconstructed using ISR sequence data. The P. gingivalis strains examined showed a maximum divergence in the ISR of 2.5%.

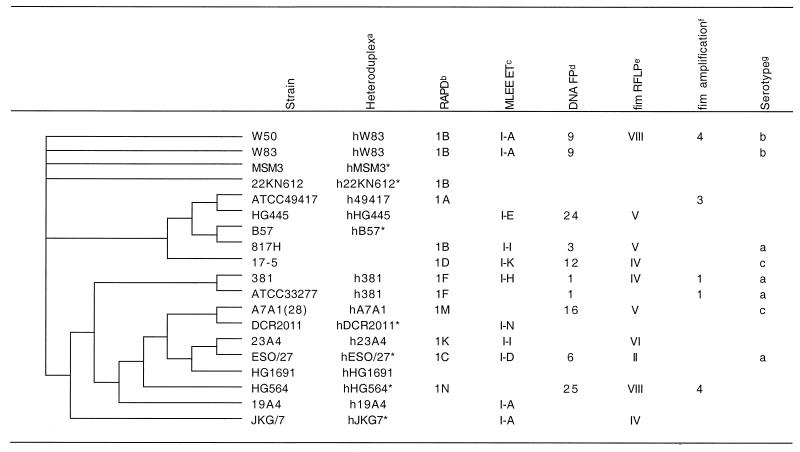

Table 1 shows the consensus heuristic parsimony tree derived from the ISR sequences for 19 laboratory strains of P. gingivalis. While there are sequence differences between MSM3, 22KN612, and W50-W83, they do not provide informative sites for parsimony analysis. The relationship between all other strains was reconstructed. A neighbor-joining distance tree constructed from the same alignment used to generate the parsimony tree is shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of ISR-based parsimony reconstruction to previous methods

Modified from Leys et al. (12). Heteroduplex types marked with an asterisk were determined in the current study.

From Menard and Mouton (16).

MLEEET, electropherotype obtained by MLEE. From Loos et al. (14).

From Loos et al. (15).

From Loos and Dyer (13).

From Amano et al. (1).

From Fisher et al. (5).

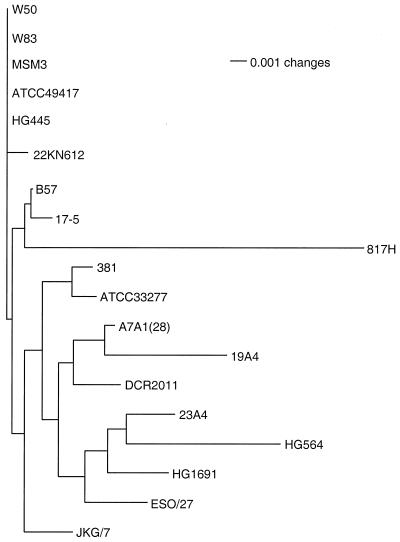

FIG. 1.

Neighbor-joining distance tree constructed from the ribosomal ISR sequences of 19 P. gingivalis laboratory strains. Branch lengths are proportional to phylogenetic distance.

Comparison of ISR sequence-based phylogeny and heteroduplex types.

Heteroduplex types for 12 laboratory strains and amplification products from 19 clinical samples were obtained from a previous study (12, 18). In addition, heteroduplex types were determined for seven strains of P. gingivalis which had not been typed previously. These seven strains are marked by an asterisk in Table 1; all seven strains were found to exhibit novel heteroduplex types.

A heuristic parsimony tree was constructed from the ISR sequences of amplification products from 19 clinical samples and 19 laboratory strains (data not shown) to allow comparison of the ISR sequence-based phylogeny to the groupings determined by heteroduplex analysis. Twelve of the 19 amplicons from clinical samples showed unique heteroduplex types. Examination of the tree showed that two of the remaining seven amplicons were phylogenetically most closely related to the laboratory strain with the same heteroduplex type. Two additional amplicons were equidistant from their heteroduplex type match and a second, nonmatching heteroduplex type. One clinical amplicon was removed from its matching type by a single node. The remaining two amplicons grouped in a clade separate from their heteroduplex type match.

DISCUSSION

While the 16S ribosomal gene is the standard for distinguishing among bacterial species, it is insufficiently variable among P. gingivalis strains for resolution. The ribosomal ISR is the most variable portion of the ribosomal operon and is sufficiently variable within a species to resolve strains (18). This locus also offers a technical advantage since it can be amplified with species-specific and conserved primers in the 16S and 23S ribosomal genes, thus avoiding the need to culture bacteria from clinical specimens. There are four copies of the ribosomal operon in P. gingivalis (P. gingivalis genome project [http://www.forsyth.org/pggp/number_of_rrna_operons.htm]). Ribosomal operons in general, including the ISR, are maintained by concerted evolution (2, 4). This correction minimizes replacement by exogenous sequences, so that the operon should closely reflect the evolutionary history of the organism.

We have previously used the ISR for both sequence-based and heteroduplex type-based P. gingivalis strain identification (12, 18). In the present study we determined the phylogenetic relationships of 19 strains of P. gingivalis and compared the trees to previously published data on strain resolution and grouping using heteroduplex analysis and other methods (Table 1).

Because distance and parsimony analyses extract different information from an alignment, some differences can be expected between the resulting trees. Distance analysis, which uses only base substitutions and ignores gaps, gives information on divergence by indicating the relative number of changes as branch lengths. Parsimony analysis, which interprets gaps as a fifth possible nucleotide state, reconstructs the evolutionary history by using both substitutions and gaps as informative sites. The basic topology of P. gingivalis was similar in both distance (Fig. 1) and parsimony (Table 1) reconstructions. The trees can be broken into two major clades: the W83 clade, which contains strains W83, W50, MSM3, and 22KN612, and a large clade, which contains the remaining strains. Strains HG445 and ATCC 49417, which were members of the W83 clade in the distance reconstruction, were separated from the W83 clade by two nodes in the parsimony analysis but were still very closely linked to one another. Both reconstructions placed strains B57, 817H, and 17-5 in a single group. Strains 381 and ATCC 33277 were closely linked in both trees, as were strains DCR2011 and A7A1(28). With the exception of the placement of strain 19A4, the topologies of the two trees were similar. The greatest confidence can be placed in trees supported by both parsimony and distance phylogenetic reconstruction methods.

Menard and Mouton (16) used RAPD analysis to reconstruct the phylogeny of P. gingivalis strains. Strains closely related by ISR sequencing were also found to be closely related by RAPD analysis, although the overall tree topology showed some rearrangements (Table 1). A MLEE-based phylogeny (14) showed very little similarity to either ISR or RAPD analysis-based reconstructions.

Although sequence analysis of the ISR provides additional resolution compared to that obtained by heteroduplex analysis, it cannot be used directly on clinical samples without cultivation or cloning when multiple strains are present. Samples that contain multiple strains are common (12), and for this reason, heteroduplex analysis provides a better option for clinical epidemiologic studies. To examine the agreement between ISR heteroduplex typing and ISR sequence-based phylogeny, the P. gingivalis ISR heteroduplex types from laboratory strains and those amplified from clinical samples were compared. Strain identification based on ISR heteroduplex typing rarely (2 of 19 strains) disagreed with ISR-based phylogeny. Many clinical amplification products yielded novel heteroduplex types. Of the seven clinical isolates whose heteroduplex types matched known laboratory strains, five grouped within one node of their heteroduplex type strain. The remaining two isolates were farther removed from their type strain. These inconsistencies result from the relatively greater sensitivity of heteroduplex analysis to multiple-base insertion or deletion events than to single-base changes. The ISR-based phylogeny shown in Table 1 weighs both of these events equally.

Strains of P. gingivalis are heterogeneous with respect to tissue damage and mortality in animal models (6, 7, 17, 20). Although these animal studies may not precisely model the etiology of P. gingivalis in human periodontitis (11), they do show that strains of P. gingivalis possess phenotypic differences. Recently, the distribution of P. gingivalis strains in human disease has been examined by Griffen et al. (9). In a study that compared samples from healthy controls and subjects with periodontitis, the strength of association with disease was determined for six different ribosomal ISR heteroduplex types. Heteroduplex types hW83 and h49417 are strongly associated with periodontitis, with odds ratios for their presence in periodontitis of 9.6 and 8.6, respectively (9). Strains W83 and ATCC 49417 were closely linked in the ISR parsimony tree (Table 1) and were found in the same clade in the distance tree (Fig. 1). Heteroduplex types hHG1691, h381, h23A4, and hA7A1 are not as strongly associated with periodontitis (odds ratios, 3.3, 2.3, 2.5, and 1.7, respectively) (9), although the relationship is statistically significant for hHG1691. Strains with these heteroduplex types, h381, h23A4, hA7A1, and hHG1691, were found in a large clade which is well separated from strains W83 and ATCC 49417 in both the distance (Table 1) and the parsimony (Fig. 1) trees. The proximity of the two strains most strongly associated with disease, strains W83 and ATCC 49417, and their separation from less virulent strains suggest a relationship between pathogenicity and phylogeny.

In summary, both distance and parsimony approaches to phylogenetic reconstruction of P. gingivalis strains by using the ISR sequence showed similar topologies. This phylogeny showed some agreement with a previous reconstruction based on RAPD analysis. Strain identification based on ISR heteroduplex typing showed a close although not complete agreement with ISR sequence-based phylogeny. The two strains of P. gingivalis whose heteroduplex types are strongly associated with periodontitis were found to be closely related and well separated from strains whose heteroduplex types are less strongly associated with disease, suggesting a relationship between pathogenicity and phylogeny.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Jeremy Wanzer for technical assistance and Christopher Cutler and Denis Mayrand for providing strains.

This study was supported by grant DE10467 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano A, Nakagawa I, Kataoka K, Morisaki I, Hamada S. Distribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains with fimA genotypes in periodontitis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1426–1430. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1426-1430.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnheim N. Concerted evolution of multigene families. In: Nei M, Koen R K, editors. Evolution of genes and proteins. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1983. pp. 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck J D. Methods of assessing risk for periodontitis and developing multifactorial models. J Periodontol. 1994;65(5 Suppl.):468–478. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.5s.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D D, Wensink P C, Jordan E. A comparison of the ribosomal DNA's of Xenopus laevis and Xenopus mulleri: the evolution of tandem genes. J Mol Biol. 1972;63:57–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher J G, Zambon J J, Genco R J. Identification of serogroup-specific antigens among Bacteroides gingivalis. J Dent Res. 1987;66:222. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genco C A, Cutler C W, Kapczynski D, Maloney K, Arnold R R. A novel mouse model to study the virulence of and host response to Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1255–1263. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1255-1263.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grenier D, Mayrand D. Selected characteristics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:738–740. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.738-740.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffen A L, Becker M R, Lyons S R, Moeschberger M L, Leys E J. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3239–3242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3239-3242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffen A L, Lyons S R, Becker M R, Moeschberger M L, Leys E J. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain variability and periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4028–4033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4028-4033.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffajee A D, Cugini M A, Tanner A, Pollack R P, Smith C, Kent R L, Jr, Socransky S S. Subgingival microbiota in healthy, well-maintained elder and periodontitis subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz J, Ward D C, Michalek S M. Effect of host responses on the pathogenicity of strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:309–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leys E J, Smith J H, Lyons S R, Griffen A L. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains by heteroduplex analysis and detection of multiple strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3906–3911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3906-3911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loos B G, Dyer D W. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the fimbrillin locus, fimA, of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1173–1181. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710050901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loos B G, Dyer D W, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Genetic structure of populations of Porphyromonas gingivalis associated with periodontitis and other oral infections. Infect Immun. 1993;61:204–212. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.204-212.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loos B G, Mayrand D, Genco R J, Dickinson D P. Genetic heterogeneity of Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis by genomic DNA fingerprinting. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1488–1493. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690080801. . (Erratum, 69:1624.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menard C, Mouton C. Clonal diversity of the taxon Porphyromonas gingivalis assessed by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2522–2531. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2522-2531.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roeterink C H, van Steenbergen T J, de Jong W F, de Graaff J. Histopathological effects in the palate of the rat induced by injection with different black-pigmented Bacteroides strains. J Periodontal Res. 1984;19:292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rumpf R W, Griffen A L, Wen B G, Leys E J. Sequencing of the ribosomal intergenic spacer region for strain identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2723–2725. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2723-2725.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swofford D L. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, 3.5p ed. Vol. 1. Champaign: Illinois Natural History Survey; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Steenbergen T J, Kastelein P, Touw J J, de Graaff J. Virulence of black-pigmented Bacteroides strains from periodontal pockets and other sites in experimentally induced skin lesions in mice. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]