Abstract

A spiral-shaped bacterium with bipolar, single, nonsheathed flagella was isolated from the feces of Syrian hamsters. The bacterium grew as a thin spreading film at 37°C under microaerobic conditions, did not hydrolyze urea, was positive for catalase and alkaline phosphatase, reduced nitrate to nitrite, did not hydrolyze hippurate, and was sensitive to nalidixic acid but resistant to cephalothin. Sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and biochemical and phenotypic criteria indicate that the novel bacterium is a helicobacter. The novel bacterium is most closely related to the recently described mouse enteric helicobacter, Helicobacter rodentium. This is the first urease-negative Helicobacter species with nonsheathed flagella isolated from feces of asymptomatic Syrian hamsters. We propose to name this novel helicobacter Helicobacter mesocricetorum. The type strain is MU 97-1514 (GenBank accession number AF072471).

Helicobacter is a rapidly expanding bacterial genus whose members have been identified in numerous host animals. The type species, Helicobacter pylori, colonizes the human stomach and was initially associated with chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease (15, 16); however, gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoma (2, 26) are now also known sequelae of infection. Since the discovery of H. pylori, a growing number of pathogenic and commensal helicobacters have been isolated from the digestive tracts of a wide variety of domestic animals. The majority of helicobacters have been associated with infection of the gastrointestinal tract; however, several recently described helicobacters have been isolated from the livers and associated with hepatic diseases of mice and hamsters (6, 9).

Numerous Helicobacter species and the closely related bacterium “Flexispira rappini” have been isolated from laboratory rodents (6, 8, 9, 14, 17, 20, 21). Several of these newly emerging digestive tract pathogens, including H. hepaticus, H. bilis, and H. rodentium, have been associated with lesions (22, 25) that could potentially interfere with biomedical research. A newly described urease-negative Helicobacter species has been associated with colitis and typhlitis in interleukin 10-deficient mice and moderate to severe typhlocolitis in immunodeficient CB17 scid/scid mice (8a, 9a). H. muridarum, H. trogontum, H. rodentium and “F. rappini” have been isolated from both asymptomatic and diseased mice or rats; however, their true pathogenic potential awaits additional study.

In contrast to the growing characterization of the helicobacter flora of these mice and rats, the helicobacter flora of Syrian hamsters is not well described. H. cinaedi was isolated from the intestinal tracts of hamsters (10), and even though this bacterium is a human pathogen that is associated with enteritis, proctocolitis, and asymptomatic rectal infections in immunocompromised people (24), no lesions have been detected in hamsters. Gebhart et al. (10) have proposed that hamsters serve as a reservoir species for zoonotic infection of humans by H. cinaedi. Recently, a newly recognized helicobacter, H. cholecystus, was isolated from the gallbladders of hamsters with cholangiofibrosis and centrilobular pancreatitis by Franklin and colleagues (9). During preliminary studies designed to investigate the pathogenesis of H. cholecystus, we found that hamsters were infected by a number of previously uncharacterized helicobacters. In this report we describe the isolation of a novel helicobacter from the feces of asymptomatic Syrian hamsters. We propose to name this bacterium Helicobacter mesocricetorum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Eight asymptomatic Syrian hamsters, from two different genetic stocks, were obtained from two geographically separate sources: one in Europe (four hamsters) and the other in the United States (four hamsters). While at the University of Missouri, all hamsters were individually housed in polycarbonate microisolator cages on Paperchip laboratory animal bedding (Canbrands International, Ltd., Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada) and were fed autoclavable laboratory rodent diet 5010 (Purina Mills, Inc., Richland, Ind.) and tap water ad libitum. Microisolator cages, bedding, feed, and water were autoclaved prior to use, and all cage changes were performed in a laminar flow hood. Sentinel hamsters from each group were submitted to the University of Missouri Research Animal Diagnostic and Investigative Laboratory for comprehensive necropsy evaluation. Serologic analyses for Sendai virus, pneumonia virus of mice, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, simian virus 5, reovirus 3, Clostridium piliforme, and Encephalitozoon cuniculi were negative. Examination for internal and external parasites and culture of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts for adventitious pathogenic bacteria was also negative. Hamsters were housed in an animal care facility accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International in accordance with a University of Missouri Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol.

Bacterial isolation.

Several fecal pellets were aseptically collected from each hamster, solubilized in 1.5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and centrifuged at low speed (approximately 500 × g) for 5 min. The fecal supernatants were collected and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate filters (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.) and streaked onto multiple plates of Trypticase soy agar that contained 5% sheep blood (blood agar). Plates were incubated for 48 to 72 h at 37°C in a microaerobic environment (6) that was created by flushing a vented jar with a gas mixture of 90% N2, 5% CO2, and 5% H2 for 1 min. Pinpoint colonies were harvested with a sterile bacterial loop and subcultured on blood agar plates to ensure that each isolate represented a pure culture. Additionally, an inoculating loop of bacteria was suspended in a drop of sterile PBS and motility was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy.

Biochemical characterization.

To identify the bacterial isolates, phenotypic tests commonly used to characterize helicobacters were performed (6). Growth was examined under aerobic, microaerobic, and anaerobic conditions at 37°C, and tolerance to 1% (wt/vol) glycine and 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium chloride was determined as previously described (8). Bacteria were Gram stained, tested for urease activity by a selective rapid urea test (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.), and tested for the enzymes catalase and alkaline phosphatase utilizing the An-Ident system (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.). Dihydrogen sulfide production, γ-glutamyltransferase activity, hippurate hydrolysis, and nitrate reduction were determined with the Campy identification system (bioMerieux Vitek). Antibiotic sensitivity was determined by the Kirby-Bauer method (1).

Electron microscopy.

Bacteria from two separate fecal isolates were grown for 24 to 48 h on blood agar plates at 37°C in a microaerobic environment. An inoculating loop was used to gently scrape a small amount of bacteria off the blood agar plate; the bacteria were then suspended in 150 μl of sterile PBS. A drop of the bacterial suspension was stained with an equal volume of 4% phosphotungstic acid solution, adsorbed onto a carbon-coated copper grid, and examined with a Hitachi H-6700 transmission electron microscope.

DNA isolation and generic Helicobacter PCR.

Representative pinpoint colonies from the fecal isolates of all eight hamsters were subcloned on blood agar and grown for 24 to 48 h at 37°C in a microaerobic environment. An inoculating loop of bacteria was gently scraped from each of the blood agar plates and individually suspended in 150 μl of sterile PBS. Bacterial DNA was then extracted from this suspension with a QiAmp tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's directions. To determine if the isolates were helicobacters, bacterial DNA was amplified utilizing PCR with the Helicobacter genus-specific primers H276f and H676r as previously described (Table 1) (18). PCR products were visualized on a 1.25% (wt/vol) NuSieve agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) stained with ethidium bromide.

TABLE 1.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene sequence of H. mesocricetorum

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Positionb |

|---|---|---|

| Broad range bacterial | ||

| C70f | AGA GTT TGA TYM TGG C | 8–23 |

| B37r | TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG A | 1513–1495 |

| Helicobacter sequencing | ||

| H419r | AAT CCT AAA ACC TTC ATC CTC | 419–406 |

| H593f | TAA GTC AGA TGT GAA ATC C | 593–611 |

| Helicobacter genus specific | ||

| H276f | TAT GAC GGG TAT CCG GC | 277–293 |

| H676r | ATT CCA CCT ACC TCT CCC A | 676–658 |

| H. mesocricetorum specific | ||

| Hm197f | GAG GGA AAG TTT TTC GCT ATG A | 197–225 |

| Hm859r | TGC ATT ACT GCA AAG ACA AGC TT | 859–844 |

Standard International Union of Biochemistry codes for bases and ambiguity.

The positions within the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene sequence that correspond to the 5′ and 3′ ends of each primer are shown. Approximate positions are given for Helicobacter-specific primers.

16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene was performed as previously described (9). Briefly, DNA templates were prepared by PCR amplification of bacterial DNA using the primer sets (i) C70f and H676r and (ii) H276f and B37r (Table 1), followed by isolation on 3.5% polyacrylamide gels. Sequencing reactions were performed by PCR using gel-purified 16S rRNA gene templates, the primers in Table 1, and a commercially available Taq dideoxy chain termination sequencing kit (Taq Dye Terminator Cycle sequencing kit; Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequence analyses were performed with the GCG software package (Genetics Computer Group, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Sequences of closely related bacteria were obtained from GenBank and compared to the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the hamster fecal isolates (Table 2). Evolutionary distances between aligned sequences and corrected distances, calculated using the Jukes-Cantor method, were determined, and a similarity matrix was constructed (13). A bootstrapped phylogenetic tree was created using the neighbor-joining method (19).

TABLE 2.

Sources and accession numbers of the strains used

| Taxon | Strain | Other designation(s) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helicobacter mesocricetorum | MU 97-1514 | ATCC 700932 | AF072471 |

| Helicobacter mesocricetorum | MU 97-5506 | AF072334 | |

| Helicobacter sp. hamster B | Hamster B | AF072333 | |

| “Flexispira rappini” | ATCC 43879 | M88138 | |

| “Gastrospirillum hominis” | Isolate 1 | L10079 | |

| Helicobacter sp. Bird B | Seymour B10 | CCUG 29256, ATCC 51480 | M88139 |

| Helicobacter sp. Bird C | Seymour B52 | CCUG 29561, ATCC 51482 | M88144 |

| Helicobacter acinonychis | Eaton 90-119-3 | ATCC 51101, CCUG 29263 | M88148 |

| Helicobacter bilis | Fox Hb1 | ATCC 51630 | U18766 |

| Helicobacter bizzozeronii | 865-2 | AF103883 | |

| Helicobacter canis | NCTC 12739 | L13464 | |

| Helicobacter cholecystus | Hkb-1 | U46129 | |

| Helicobacter cinaedi | CCUG 18818 | ATCC 35683 | M88150 |

| Helicobacter felis | Lee CS1 | ATCC 49179 | M57389 |

| Helicobacter fennelliae | CCUG 18820 | ATCC 35684 | M88154 |

| Helicobacter hepaticus | Fox Hh-2 | ATCC 51448 | U07574 |

| Helicobacter muridarum | Lee ST1 | CCUG 29262, ATCC 49282 | M80205 |

| Helicobacter mustelae | Fox R85-13-6 | ATCC 43772 | M35048 |

| Helicobacter nemestrinae | ATCC 49396 | X67854 | |

| Helicobacter pametensis | Seymour B9 | CCUG 29255, ATCC 51478 | M88147 |

| Helicobacter pullorum | NCTC 12824 | L36141 | |

| Helicobacter pylori | ATCC 43504 | M88157 | |

| Helicobacter rodentium | MIT 95-1707 | ATCC 700285 | U96296 |

| Helicobacter salomonis | Inkinen | U89351 | |

| Helicobacter trogontum | LRB 8581 | ATCC 700114 | U65103 |

| “Helicobacter typhlonicus” | MU 96-1 | AF061104 | |

| Wolinella succinogenes | Tanner 602W | ATCC 29543 | M88159 |

| Campylobacter coli | CCUG 11283 | L04312 |

Identification of strains by PCR with specific primers.

Species-specific PCR primers were designed to amplify a 630-bp segment of the 16S rRNA gene of H. mesocricetorum. All reactions were performed in a 50-μl final volume using a Perkin-Elmer 2400 thermocycler. PCR mixtures contained each oligonucleotide primer, Hm197f and Hm859r (Table 1), at a final concentration of 0.8 μM, 200 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl [pH 8.3]), 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim), and approximately 5 ng of bacterial DNA. Samples were heated to 94°C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 2 s, 63°C for 2 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. PCR products (15 μl) were electrophoretically separated using a 1.25% NuSieve agarose gel (FMC BioProducts), stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV transillumination. Standardized DNA molecular weight markers were used to estimate the lengths of PCR amplicons. For comparison, 16S rRNA genes from other helicobacters were amplified with the generic PCR primers H276f and H676r as previously described (18).

Histopathology.

Infected and uninfected Syrian hamsters were euthanatized by inhalant overdose of carbon dioxide and necropsied. Biopsies of the liver and lower digestive tract were collected and preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Longitudinal sections of the liver, jejunum, ileocecocolonic region, cecal tip, and colon were trimmed and paraffin embedded. The paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were cut into 5-μm-thick sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined by a laboratory animal veterinarian experienced in comparative pathology.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences for H. mesocricetorum strains MU 97-1514 and MU 97-5506 are available from the GenBank under accession numbers AF072471 and AF072334, respectively. A single isolate of an additional uncharacterized helicobacter was recovered from one of the hamsters in this study and tentatively called Helicobacter sp. hamster B. The 16S rRNA sequence of this isolate, which contains an intervening sequence, was determined and is available from GenBank under accession number AF072333.

RESULTS

Bacterial isolation and growth characteristics.

Pure cultures of bacteria were identified in filtered 37°C microaerobic fecal cultures of all eight hamsters. The isolates grew as pinpoint colonies or as thin spreading films. Slight to no growth was noted under similar anaerobic conditions. The bacteria grew well under microaerobic conditions at 42°C but did not grow under similar conditions at 25°C. No growth was noted under aerobic conditions at 37°C. Phase-contrast microscopy indicated that all bacteria were spiral in shape and had characteristic darting motility. Results from biochemical and growth analyses commonly used to characterize helicobacters suggested that all isolates were members of the Helicobacter genus (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Biochemical and morphologic characteristics of H. mesocricetorum in comparison to those of closely related helicobacters

| Characteristic | H. mesocricetoruma | H. rodentium | H. pullorum | H. pametensis | H. cholecystus | H. cinaedi | H. hepaticus | H. muridarum | H. trogontum | H. bilis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalase | 7/7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Urease | 0/7 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 7/7 | − | − | + | + | − | NDc | + | − | ND |

| γ-Glutamyltransferase | 0/7 | − | − | − | − | − | ND | + | + | ND |

| H2S production | 0/7 | ND | ND | − | − | − | + | + | ND | + |

| Hippurate hydrolysis | 0/7 | ND | ND | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND |

| Nitrate reduction | 6/7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Periplasmic fibers | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| No. of flagella | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1–2 | 2 | 10–14 | 5–7 | 3–14 |

| Location | Bipolar | Bipolar | Polar | Bipolar | Polar | Polar, bipolar | Bipolar | Bipolar | Bipolar | Bipolar |

| Flagellar sheath | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1% glycine | 0/7 | + | ND | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| 1.5% NaCl | 0/7 | ND | ND | − | − | −b | + | − | − | − |

| 37°C | 7/7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cephalothind | 6/6 | R | S | S | R | I | R | R | R | R |

| Nalidixic acidd | 1/6 | R | R | S | I | S | R | R | R | R |

| Reference | 21 | 23 | 5 | 9 | 10, 12 | 6 | 14 | 17 | 8 |

Number of strains positive or resistant/number of strains tested.

Growth in 2% NaCl.

ND, not determined.

R, resistant; S, susceptible; I, intermediate.

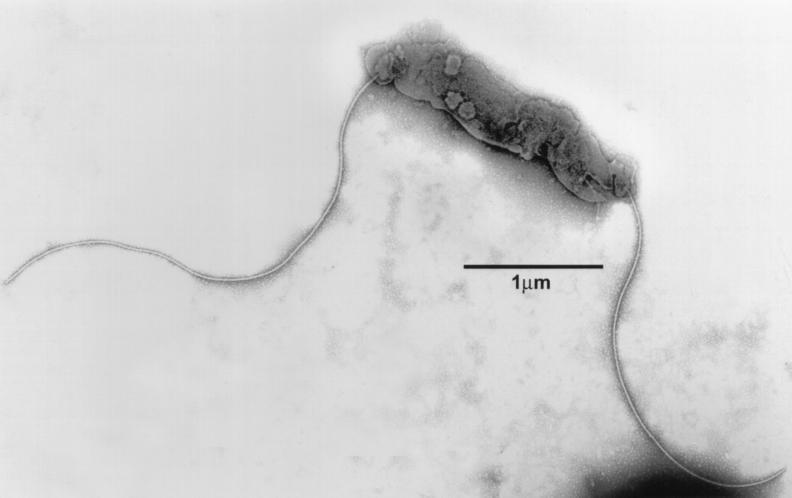

Ultrastructure.

Approximately 95% of bacteria were spirally curved rods with singular bipolar nonsheathed flagella (11) and no periplasmic fibers (Fig. 1). The rods averaged 2.5 μm in length and 0.5 μm in diameter. The general morphology and flagellar number and location were used to compare to other known helicobacters (Table 3). The remaining 5% of bacteria were coccoid forms similar to those described for other in vitro-cultured helicobacters (3, 4).

FIG. 1.

Electron micrograph of a negatively stained preparation of H. mesocricetorum. Note that the spirally curved cell has single bipolar nonsheathed flagella.

Biochemical and physiological characteristics.

Biochemical and physiological properties of seven H. mesocricetorum isolates were compared with similar properties of previously described Helicobacter spp. (Table 3). H. mesocricetorum was negative for the enzymes urease and γ-glutamyltransferase, did not hydrolyze hippurate, and did not produce H2S. H. mesocricetorum was positive for the enzymes catalase and alkaline phosphatase and reduced nitrate to nitrite. All H. mesocricetorum strains tested were resistant to the antibiotic cephalothin, while five of six strains tested were sensitive to nalidixic acid.

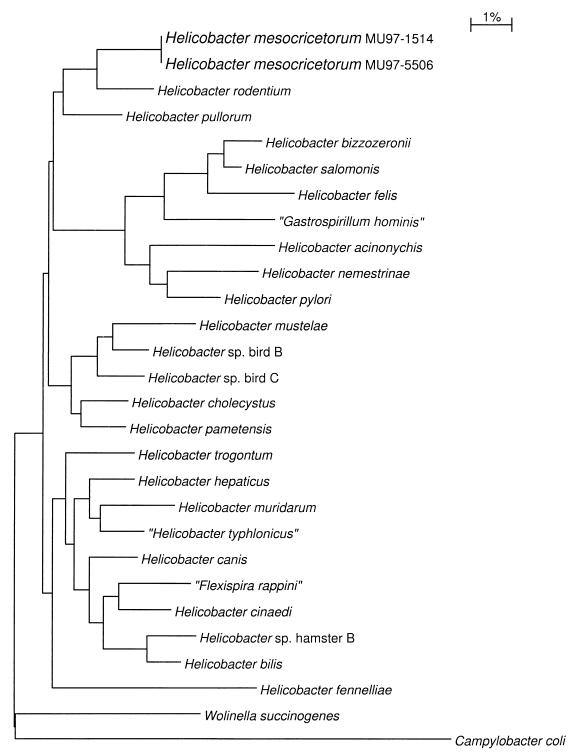

Phylogenetic analysis.

PCR amplification of DNA from all eight isolates, utilizing Helicobacter genus-specific primers (18), resulted in appropriately sized amplicons, providing additional evidence that the bacterial isolates were helicobacters. A partial sequence of the 16S rRNA gene from all eight isolates was determined. Six of eight isolates were isogenic, the seventh isolate varied by a single nucleotide (99.93% similarity), and the eighth isolate was genetically distinct from the other seven helicobacter strains. Isolates 1 to 7 were considered a single species that we have tentatively named Helicobacter mesocricetorum. The genetically distinct isolate was 94.71% identical to H. mesocricetorum, and because of the relatively low percent identity between 16S rRNA genes, this isolate was not considered a member of the H. mesocricetorum species. We have provisionally called this additional helicobacter isolate Helicobacter sp. hamster B. Novel helicobacter 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared to similar sequences from 26 members of the genera Helicobacter, Wolinella, and Campylobacter (Table 2). These data were used to construct a similarity matrix based on the method of Jukes and Cantor (13) and an uncorrected difference matrix (Table 4). These data were also used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method (19) (Fig. 2). Sequence analysis revealed that Helicobacter mesocricetorum is most closely related to H. rodentium (96.97% similar); H. mesocricetorum also clustered in the same group with H. pullorum (96.32% similar).

TABLE 4.

Similarity matrix based on 16S rRNA sequence comparisons

| Taxona | % Similarity or % differenceb

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. mesocricetorum | H. rodentium | H. pullorum | H. hepaticus | H. muridarum | H. trogontum | “F. rappini” | H. cinaedi | H. canis | H. bilis | H. fennelliae | Helicobacter sp. Bird B | H. mustelae | Helicobacter sp. Bird C | H. cholecystus | H. pametensis | H. salomonis | H. acinonychis | H. pylori | H. nemestrinae | |

| H. mesocricetorum | 97.0 | 96.4 | 94.6 | 93.4 | 95.3 | 93.0 | 94.2 | 94.8 | 93.8 | 92.1 | 94.5 | 93.7 | 94.6 | 95.0 | 96.0 | 91.7 | 91.7 | 93.7 | 92.2 | |

| H. rodentium | 3.0 | 96.2 | 95.1 | 93.7 | 95.0 | 93.4 | 94.4 | 95.3 | 94.0 | 91.8 | 94.5 | 93.3 | 94.4 | 95.5 | 95.2 | 92.2 | 91.3 | 93.3 | 92.2 | |

| H. pullorum | 3.7 | 3.9 | 96.0 | 94.4 | 96.2 | 94.0 | 94.5 | 96.2 | 94.6 | 93.0 | 95.4 | 94.1 | 95.5 | 96.8 | 97.0 | 93.7 | 92.5 | 94.3 | 92.9 | |

| H. hepaticus | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 96.6 | 97.2 | 95.2 | 95.8 | 96.9 | 95.4 | 92.6 | 95.7 | 94.7 | 95.7 | 96.3 | 95.8 | 92.6 | 91.6 | 92.6 | 92.0 | |

| H. muridarum | 6.9 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 95.5 | 94.2 | 94.1 | 95.2 | 93.6 | 92.0 | 95.4 | 94.0 | 95.9 | 95.3 | 95.4 | 91.0 | 91.3 | 92.0 | 90.5 | |

| H. trogontum | 4.8 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 93.9 | 95.5 | 96.2 | 94.9 | 93.0 | 96.3 | 95.1 | 95.5 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 92.1 | 90.8 | 92.2 | 91.5 | |

| “F. rappini” | 7.3 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 97.0 | 95.7 | 94.8 | 91.6 | 94.2 | 93.7 | 95.0 | 94.4 | 94.8 | 90.8 | 90.6 | 91.8 | 90.6 | |

| H. cinaedi | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 96.6 | 95.5 | 92.6 | 94.2 | 93.6 | 94.4 | 94.8 | 94.3 | 91.7 | 90.7 | 91.8 | 91.3 | |

| H. canis | 5.3 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 96.7 | 92.3 | 95.9 | 94.6 | 96.0 | 96.5 | 95.7 | 92.5 | 91.3 | 92.7 | 91.8 | |

| H. bilis | 6.5 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 91.3 | 94.0 | 93.0 | 94.3 | 95.0 | 94.6 | 90.6 | 89.4 | 91.0 | 90.4 | |

| H. fennelliae | 8.3 | 8.7 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 91.3 | 90.8 | 91.3 | 92.1 | 92.3 | 90.1 | 88.7 | 90.2 | 89.0 | |

| Helicobacter sp. Bird B | 5.8 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 9.3 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 96.6 | 97.3 | 92.6 | 92.1 | 93.2 | 92.1 | |

| H. mustelae | 6.6 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 96.2 | 94.9 | 95.6 | 92.2 | 91.6 | 92.8 | 91.8 | |

| Helicobacter sp. Bird C | 5.6 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 96.6 | 97.3 | 92.2 | 92.4 | 93.7 | 92.6 | |

| H. cholecystus | 5.2 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 97.7 | 93.7 | 92.0 | 93.2 | 92.9 | |

| H. pametensis | 4.1 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 93.2 | 92.6 | 94.0 | 92.7 | |

| H. salomonis | 8.8 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 93.8 | 94.0 | 93.8 | |

| H. acinonychis | 8.8 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 95.9 | 93.7 | |

| H. pylori | 6.6 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 96.5 | |

| H. nemestrinae | 8.2 | 8.3 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 12.0 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 3.6 | |

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of members of the genera Helicobacter, Campylobacter, “Flexispira,” “Gastrospirillum,” Wolinella, and Arcobacter prepared by the neighbor-joining method. Phylogenetic distances between bacteria were calculated as the sum of horizontal branches between bacteria. The bar represents one base substitution per 100 nucleotides (1%).

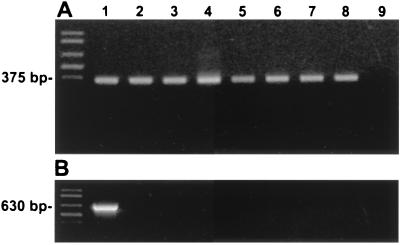

PCR identification of strains.

PCR amplification of DNA from eight Helicobacter species, representing a wide variety of helicobacters, was tested with genus-specific primers H276f and H676r. All bacteria tested produced the expected 375-bp amplicon (Fig. 3A), confirming that they were helicobacters. A similar PCR utilizing H. mesocricetorum-specific primers Hm197f and Hm859r produced only the expected 630-bp amplicon in the H. mesocricetorum reaction (Fig. 3B). All seven H. mesocricetorum isolates tested produced the expected 630-bp amplicon when tested with the species-specific primer set.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis profiles of helicobacter PCR amplicons using Helicobacter genus-specific primers (A) and H. mesocricetorum species-specific primers (B). Far left, DNA molecular weight markers; lane 1, H. mesocricetorum; lane 2, H. cholecystus; lane 3, H. hepaticus; lane 4, H. bilis; lane 5, H. muridarum; lane 6, “H. typhlonicus”; lane 7, “Flexispira rappini”; lane 8, H. pylori; lane 9, no template (control).

Histologic review.

Comparison of digestive tract and liver sections from H. mesocricetorum-infected and uninfected Syrian hamsters revealed no significant histologic differences. Thus, we believe that this bacterium is a novel nonpathogenic commensal organism of the lower digestive tract of Syrian hamsters that does not cause any significant histologic lesions.

DISCUSSION

In this report we describe the isolation of a urease-negative, spirally curved bacterium from the feces of asymptomatic Syrian hamsters. Analysis of biochemical traits and morphologic characteristics and genetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene identify this bacterium as a novel member of the genus Helicobacter. This bacterium was cultured from the feces of hamsters from the United States and Europe, indicating that it is distributed widely among hamsters. There are two previous publications describing isolation of helicobacters from Syrian hamsters. Gebhart et al. (10) reported the isolation of H. cinaedi, a bacterium associated with enteritis, proctocolitis, and asymptomatic rectal infections in humans (24), and suggested that hamsters serve as a reservoir for this bacterium (10). Franklin et al. (9) reported the isolation of H. cholecystus from the gallbladders of hamsters with cholangiofibrosis and centrilobular pancreatitis. The 16S rRNA gene from H. mesocricetorum is 95.99 and 94.83% similar, respectively, to those of the two previously mentioned hamster helicobacters.

H. mesocricetorum is most closely related phylogenetically and biochemically to H. rodentium (96.97% similar), which was recently isolated from laboratory mice (21), and to H. pullorum (96.32% similar), which has been isolated from both humans and chickens with gastroenteritis (22). Like H. rodentium, H. mesocricetorum is unusual among murine helicobacters in that it lacks the enzyme urease. The biological advantage that urease confers to helicobacters is unknown; however, it has been postulated that urease serves to increase bacterial survival within the low-pH environment of the stomach (7). We believe that H. mesocricetorum is a commensal organism of the intestinal tract, where the pH is more neutral, and thus the lack of urease is most likely not detrimental to the bacterium. In contrast to H. rodentium, H. mesocricetorum was able to hydrolyze phosphate, was unable to grow in the presence of 1% glycine, and was sensitive to the antibiotic nalidixic acid.

H. mesocricetorum can be differentiated from H. pullorum by morphology, as H. pullorum has a single monopolar flagellum while H. mesocricetorum has single bipolar flagella. Further, H. pullorum lacks the enzyme alkaline phosphatase, while H. mesocricetorum is positive for this enzyme.

H. mesocricetorum lacks a flagellar sheath, an unusual characteristic that it shares with two other helicobacters with which it clusters: H. rodentium (21) and H. pullorum (23). The phylogenetic significance of sheathed flagella is unknown, yet it is an unusual characteristic of most of the members of this subgroup. It is interesting that all of the known helicobacters that lack a flagellar sheath are nongastric, suggesting that the flagellar sheath may provide a means of protecting the flagellum in the acidic environment of the stomach. Histologic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tracts of H. mesocricetorum-infected Syrian hamsters did not reveal any unusual lesions; thus, this microbe is most likely a nonpathogenic enteric bacterium.

We have also developed a specific PCR assay for H. mesocricetorum. The PCR assay can be used for rapid and specific differentiation of H. mesocricetorum from other common rodent helicobacter species.

In conclusion, we have described the isolation of a novel Helicobacter species, which we have designated H. mesocricetorum, from the feces of asymptomatic Syrian hamsters. The identification of this bacterium adds to the growing list of helicobacters found in the gastrointestinal tracts of rodents. The absence of disease in these hamsters suggests that this helicobacter may be a commensal organism; however, assessment of the pathogenic potential of H. mesocricetorum awaits further study.

Description of Helicobacter mesocricetorum sp. nov.

Helicobacter mesocricetorum (the species name describes the monotypic genus from which this bacterium was first isolated). The type strain is a gram-negative, non-spore-forming, spirally curved rod-shaped bacterium (0.4 to 0.6 by 2 to 3 μm) with singular nonsheathed bipolar flagella. Bacteria grew as pinpoint colonies or as a thin spreading film in microaerobic environments at both 37 and 42°C. No growth was noted in a microaerobic environment at 25°C, and no growth occurred in aerobic or anaerobic environments at 37°C. There is no growth in the presence of 1% glycine or 1.5% sodium chloride. The bacterium has the enzymes catalase and alkaline phosphatase but lacks urease and γ-glutamyltransferase. The bacterium does not produce H2S and does not hydrolyze hippurate; however, it does reduce nitrate to nitrite. Cells are resistant to cephalothin but sensitive to nalidixic acid. The bacterium has been isolated from the feces of asymptomatic Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus). The type strain is MU 97-1514.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ana-Maria Fernandez and Beth Livingston for laboratory technical assistance, Howard Wilson for assistance with graphics layout, and Preston Stogsdill for assistance with electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer A W, Kirby W M, Sherris J C, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser M J, Kobayashi K, Cover T L, Cao P, Feurer I D, Perez-Perez G I. Helicobacter pylori infection in Japanese patients with adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:799–802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cellini L, Allocati N, Angelucci D, Iezzi T, Di Campli E, Marzio L, Dainelli B. Coccoid Helicobacter pylori not culturable in vitro reverts in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cellini L, Allocati N, Di Campli E, Dainelli B. Helicobacter pylori: a fickle germ. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewhirst F E, Seymour C, Fraser G J, Paster B J, Fox J G. Phylogeny of Helicobacter isolates from bird and swine feces and description of Helicobacter pametensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:553–560. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox J G, Dewhirst F E, Tully J G, Paster B J, Yan L, Taylor N S, Collins M J, Jr, Gorelick P L, Ward J M. Helicobacter hepaticus sp. nov., a microaerophilic bacterium isolated from livers and intestinal mucosal scrapings from mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1238–1245. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1238-1245.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox J G, Lee A. Gastric helicobacter infection in animals: natural and experimental infections. In: Goodwin C S, Worsley B W, editors. Biology and clinical practice. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 407–430. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox J G, Yan L L, Dewhirst F E, Paster B J, Shames B, Murphy J C, Hayward A, Belcher J C, Mendes E N. Helicobacter bilis sp. nov., a novel Helicobacter species isolated from bile, livers, and intestines of aged, inbred mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:445–454. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.445-454.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Fox J G, Gorelick P L, Kullberg M C, Ge Z, Dewhirst F E, Ward J M. A novel urease-negative Helicobacter species associated with colitis and typhlitis in IL-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1757–1762. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1757-1762.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin C L, Beckwith C S, Livingston R S, Riley L K, Gibson S V, Besch-Williford C L, Hook R R., Jr Isolation of a novel Helicobacter species, Helicobacter cholecystus sp. nov., from the gallbladders of Syrian hamsters with cholangiofibrosis and centrilobular pancreatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2952–2958. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2952-2958.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Franklin C L, Riley L K, Livingston R S, Beckwith C S, Hook R R, Jr, Besch-Williford C L, Hunziker R, Gorelick P L. Enteric lesions in SCID mice infected with “Helicobacter typhlonicus,” a novel urease-negative Helicobacter species. Lab Anim Sci. 1999;49:496–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebhart C J, Fennell C L, Murtaugh M P, Stamm W E. Campylobacter cinaedi is normal intestinal flora in hamsters. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1692–1694. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1692-1694.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geis G, Leying H, Suerbaum S, Mai U, Opferkuch W. Ultrastructure and chemical analysis of Campylobacter pylori flagella. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:436–441. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.436-441.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han Y H, Smibert R M, Krieg N R. Occurrence of sheathed flagella in Campylobacter cinaedi and Campylobacter fennelliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:488–490. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A, Phillips M W, O'Rourke J L, Paster B J, Dewhirst F E, Fraser G J, Fox J G, Sly L I, Romaniuk P J, Trust T J, Kouprach S. Helicobacter muridarum sp. nov., a microaerophilic helical bacterium with a novel ultrastructure isolated from the intestinal mucosa of rodents. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:27–36. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall B J. Campylobacter pylori: its link to gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl. 1):S87–S93. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_1.s87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall B J, Warren J R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;i:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendes E N, Queiroz D M, Dewhirst F E, Paster B J, Moura S B, Fox J G. Helicobacter trogontum sp. nov., isolated from the rat intestine. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:916–921. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley L K, Franklin C L, Hook R R, Besch-Williford C. Identification of murine helicobacters by PCR and restriction enzyme analyses. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:942–946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.942-946.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schauer D B, Ghori N, Falkow S. Isolation and characterization of “Flexispira rappini” from laboratory mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2709–2714. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2709-2714.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen Z, Fox J G, Dewhirst F E, Paster B J, Foltz C J, Yan L, Shames B, Perry L. Helicobacter rodentium sp. nov., a urease-negative Helicobacter species isolated from laboratory mice. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:627–634. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shomer N H, Dangler C A, Schrenzel M D, Fox J G. Helicobacter bilis-induced inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice with defined flora. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4858–4864. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4858-4864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanley J, Linton D, Burnens A P, Dewhirst F E, On S L, Porter A, Owen R J, Costas M. Helicobacter pullorum sp. nov.—genotype and phenotype of a new species isolated from poultry and from human patients with gastroenteritis. Microbiology. 1994;140:3441–3449. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Totten P A, Fennell C L, Tenover F C, Wezenberg J M, Perine P L, Stamm W E, Holmes K K. Campylobacter cinaedi (sp. nov.) and Campylobacter fennelliae (sp. nov.): two new Campylobacter species associated with enteric disease in homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:131–139. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward J M, Fox J G, Anver M R, Haines D C, George C V, Collins M J, Jr, Gorelick P L, Nagashima K, Gonda M A, Gilden R V, et al. Chronic active hepatitis and associated liver tumors in mice caused by a persistent bacterial infection with a novel Helicobacter species. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1222–1227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.16.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wotherspoon A C, Doglioni C, Diss T C, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson P G. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]