Abstract

In a new article published in JID Innovations, Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) show that type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) in the skin of mice with IL-33 overexpression in keratinocytes are heterogeneous and consist of two distinct populations: skin-resident ILC2s and circulating ILC2s. They show that the circulating subset of skin ILC2s migrates to draining lymph nodes during hapten-induced cutaneous inflammation to potentially enhance the adaptive immune response.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common skin inflammatory disease and affects 10–20% of infants in the United States and worldwide (Weidinger et al., 2018). AD lesional skin is characterized by a defective skin barrier and a type-2‒dominated local immune response (Weidinger et al., 2018). AD skin lesions demonstrate increased expression of type-2‒promoting epithelial cytokines IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25 and increased numbers of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) that express high levels of receptors for these cytokines (Alkon et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2013; Salimi et al., 2013; Savinko et al., 2012; Soumelis et al., 2002). IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25, alone or in combination, promote type 2 cytokine production by ILC2s in vitro (Salimi et al., 2013). ILC2s lack distinct lineage markers as well as antigen-specific surface receptors and are enriched at the interfaces between the body and the environment (Spits et al., 2013; Vivier et al., 2018). ILC2s express the transcription factor RORα, which is essential for their development (Wong et al., 2012) and for expression of type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) (Spits et al., 2013; Vivier et al., 2018).

Clinical Implications.

-

•

Skin type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) in skin-specific Il33‒transgenic mice are a heterogeneous population.

-

•

Skin-resident ILC2s and circulating ILC2s exhibit distinctive phenotypes and functions.

-

•

Circulating ILC2s could modulate the adaptive immune response to cutaneously encountered antigens.

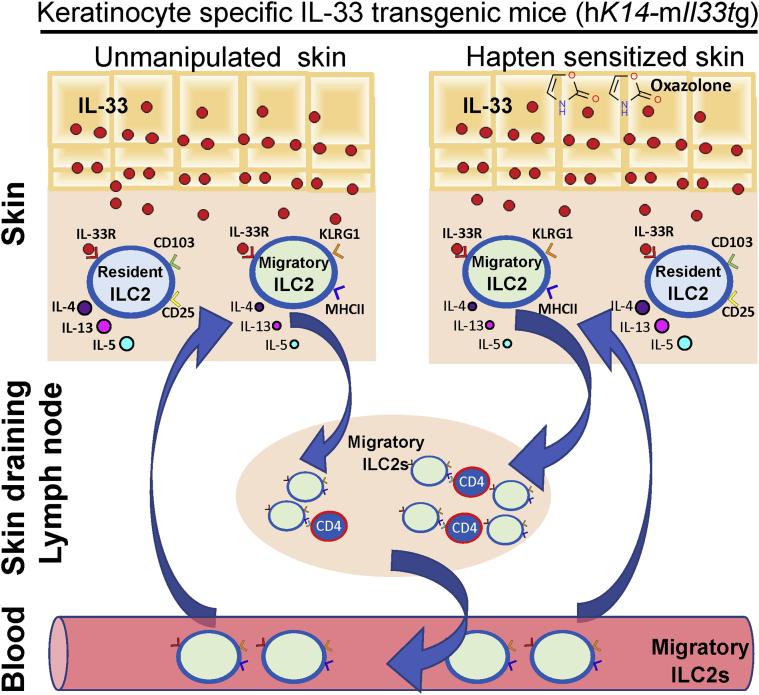

In a new article published in JID Innovations, Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) identify two distinct populations of cutaneous ILC2s by single-cell RNA-sequencing (RNAseq) analysis of skin from hK14-mIl33‒transgenic mice that overexpress IL-33 selectively in keratinocytes (KCs). Analysis of sorted ILC2s from the skin and skin-draining lymph nodes (LNs) of these mice reveals two distinct populations of ILC2s with different gene expression profiles: an ILC2 population restricted to the skin and an ILC2 population present in both the skin and the skin-draining LNs. Skin-resident ILC2s express CD103 and high levels of IL2Rα (CD25) and type 2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13, whereas circulating ILC2s express KLRG1 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules. These differences were confirmed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence. Moreover, Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) elegantly show that circulating ILC2s present in the skin but not skin-resident ILC2s migrate from the skin to draining LNs using double transgenic mice that express IL-33 in KCs as well as the photoconvertible fluorescence protein KikGR. Violet light irradiation of the skin of KikGR-transgenic mice changes the fluorescence spectrum of KikGR in cutaneous cells from green to red, allowing to track resident skin cells at the moment of irradiation. Induction of skin inflammation in oxazolone-sensitized double transgenic mice after cutaneous hapten challenge enhanced the migration of circulating ILC2s from the skin to the draining LNs (Figure 1). Thus, cutaneous ILC2s have the potential to activate the two arms of the immune response, with skin-resident ILC2s being responsible for the activation of local innate immunity, whereas circulating ILC2s present in the skin being able to potentially drive adaptive immunity by their ability to present antigen‒MHC complexes and to secrete cytokines.

Figure 1.

Schematic summary of the heterogeneity of skin ILC2s in hK14-mIl33‒transgenic mice. Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) identify two distinct populations of ILC2s in the skin of mice with keratinocyte-specific expression. Skin-resident ILC2s express CD103, high levels of CD25, and type 2 cytokines, whereas circulating ILC2s express KLRG1 and MHC class II molecules and have the capacity to migrate to draining LNs. Migration of circulating ILC2s from the skin to LNs is enhanced during oxazolone-induced contact dermatitis, raising the possibility that circulating ILC2s modulate the adaptive immune response to cutaneously encountered antigen in the skin-draining LNs. ILC2, type 2 innate lymphoid cell; LN, lymph node; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

There are some limitations to the conclusions of this elegant study. The use of skin-specific Il33-transgenic mice and the sorting strategy to isolate ILC2s for subsequent single-cell RNAseq analysis could bias the nature of ILC2s analyzed. Transgenic overexpression of Il33 in the skin together with the elevated expression of IL-33 receptor that it causes in skin ILC2s and possibly other cells, for example, mast cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and basophils, may influence directly or indirectly the ILC2 recruitment to the skin as well as their phenotype and function.

Activation of ILC2s during calcipotriol (MC903)-induced dermatitis, which is independent of adaptive immunity, highly depends on TSLP in the B6 background, whereas it depends on IL-25 in the BALB/c background (Kim et al., 2013; Salimi et al., 2013). We recently showed that the activation of ILC2s by IL-25 is essential for their IL-13 production in mouse skin epicutaneously sensitized with an allergen (Leyva-Castillo et al., 2020). Whether activation of ILC2s by epithelial cytokines other than IL-33 generates heterogeneous populations of skin ILC2s needs to be determined.

A critical question not addressed by Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) is whether the two distinct populations of cutaneous ILC2s exist in normal mouse skin or in other mouse models of skin inflammation and importantly in normal or inflamed human skin. Single-cell RNAseq analysis of healthy and AD lesional skin shows that skin ILCs are a heterogeneous population, including ILC1s, ILC2s, ILC3s, and ILC precursors, with ILC2s being predominant (Alkon et al., 2021). Furthermore, ILC2s in normal human skin were found to be a homogenous population that expresses type 2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-4 and the transcription factor GATA3, whereas ILC2s present in AD lesional skin were found to be heterogeneous and expressed type 2 as well as type 17 cytokines and the transcription factors that drive these cytokines, including GATA3, AHR, and RORC (Alkon et al., 2021). Similar ILC2 plasticity has been observed in a mouse model of psoriasis induced by recombinant IL-23 injection (Bielecki et al., 2021). These results highlight the important role of the microenvironment in ILC2 activation and plasticity in the skin.

ILC2s control the adaptive immune response locally promoting the activation of dendritic cells, suppressing Treg functions, interacting with CD4+ T cells, and inducing chemoattraction of T helper type 2 cells (Halim et al., 2018, 2016; Leyva-Castillo et al., 2020; Noval Rivas et al., 2016; Oliphant et al., 2014). The expression of MHCII molecules by circulating skin ILC2s and their migratory capacity shown by Nakatani-Kusakabe et al. (2021) raises the exciting possibility that this subpopulation of skin ILC2s modulates the adaptive immune response to cutaneously encountered antigen in skin-draining LNs.

ORCIDs

Juan-Manuel Leyva-Castillo: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7394-4457

Raif S. Geha: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6019-3751

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

See related article 2021;1:100035

Cite this article as: JID Innovations 2021;X:100059

References

- Alkon N., Bauer W.M., Krausgruber T., Goh I., Griss J., Nguyen V., et al. Single-cell analysis reveals innate lymphoid cell lineage infidelity in atopic dermatitis [e-pub ahead of print] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.025. (accessed 2021 August 12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecki P., Riesenfeld S.J., Hütter J.C., Torlai Triglia E., Kowalczyk M.S., Ricardo-Gonzalez R.R., et al. Skin-resident innate lymphoid cells converge on a pathogenic effector state. Nature. 2021;592:128–132. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03188-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim T.Y., Hwang Y.Y., Scanlon S.T., Zaghouani H., Garbi N., Fallon P.G., et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells license dendritic cells to potentiate memory TH2 cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ni.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim T.Y.F., Rana B.M.J., Walker J.A., Kerscher B., Knolle M.D., Jolin H.E., et al. Tissue-restricted adaptive type 2 immunity is orchestrated by expression of the costimulatory molecule OX40L on group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2018;48:1195–1207.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.S., Siracusa M.C., Saenz S.A., Noti M., Monticelli L.A., Sonnenberg G.F., et al. TSLP elicits IL-33-independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:170ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Castillo J.M., Galand C., Mashiko S., Bissonnette R., McGurk A., Ziegler S.F., et al. ILC2 activation by keratinocyte-derived IL-25 drives IL-13 production at sites of allergic skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1606–1614.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani-Kusakabe M., Yasuda K., Tomura M., et al. Monitoring cellular movement with photoconvertible fluorescent protein and single-cell RNA sequencing reveals cutaneous group 2 inate lymphoid cell subtypes, circulating ILC2 and skin-resident ILC2. JID Innovations. 2021;1:100035. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noval Rivas M., Burton O.T., Oettgen H.C., Chatila T. IL-4 production by group 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes food allergy by blocking regulatory T-cell function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:801–811.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliphant C.J., Hwang Y.Y., Walker J.A., Salimi M., Wong S.H., Brewer J.M., et al. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimi M., Barlow J.L., Saunders S.P., Xue L., Gutowska-Owsiak D., Wang X., et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2939–2950. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savinko T., Matikainen S., Saarialho-Kere U., Lehto M., Wang G., Lehtimäki S., et al. IL-33 and ST2 in atopic dermatitis: expression profiles and modulation by triggering factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumelis V., Reche P.A., Kanzler H., Yuan W., Edward G., Homey B., et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spits H., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J.P., Eberl G., et al. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier E., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J.P., Eberl G., et al. Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell. 2018;174:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidinger S., Beck L.A., Bieber T., Kabashima K., Irvine A.D. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.H., Walker J.A., Jolin H.E., Drynan L.F., Hams E., Camelo A., et al. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]