Abstract

Deeply rooted on human rights principles, there is a growing international agreement to prohibit non-consensual medical interventions to intersex persons. In contrast, medical protocols for intersex care in the United States are guided by clinical wisdom and guidelines that are not legally binding. But as the medical profession is called to respect and to champion the right to health within human rights principles, expert opinion in the United States has become unsettled when confronted with current standards of intersex care. In this study, we tracked the human rights arguments by international institutions that effectively impacted clinical standards for the care of intersex persons around the globe during this decade, and we studied the use of rhetoric by key policy stakeholders that seek to uphold intersex medical care in the United States to these international standards. We conclude that the medical establishment in the United States does not meet international standards of human rights as it enforces an outdated definition of ‘sex’.

Keywords: Intersexuality, standards of care, clinical guidelines, human rights, sexual rights

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2030 led by the United Nations acknowledges and relies upon the intersections and interdependency of universal human rights including those related to good health and well-being (United Nations General Assembly, 2015; Halonen et al., 2017). Deeply rooted in universal human rights principles, a number of countries have adopted the right to health and well-being in their national constitutions; most notably South Africa, Ecuador and India. Other countries have interpreted these in non-binding policies or have acknowledged them in court decisions (Singh et al., 2007). Historically, the United Sates is parsimonious when pressured to adopt treatises, policies or recommendations championed by international organisations that oversee human rights (Greenberg, 2017). For instance, the Constitution of the United States does not recognise all human rights. For the United States, sexual and reproductive health rights ‘express rights which are not legally binding. Sexual rights are not human rights and they are not enshrined in international human rights law…’ (Erdman, 2015). This position contrasts sharply with recent health policies, administrative or legal mechanisms enforced by the governments of Malta, Germany, Switzerland, Australia, Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Portugal and India to regulate or to prevent the practice of surgical interventions that remove healthy tissues or reconfigure the genitalia of intersex persons.

The medical conception of ‘sex’ relies on the consonant co-expression of chromosomes (46, XX or 46, XY), gonads (ovaries or testes), reproductive apparatus within the pelvic cavity and cosmetic appearance of the external genitalia at birth that can yield to reproduction later in life. Any variation of this biological layout that can potentially hamper reproduction is taken as dissonant to ‘female’ or ‘male’, and referred to as ‘intersexuality’. At the turn of the century, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published their recommendations for the care for intersex newborns (AAP, 2000), but retired their recommendations on October 2006 (AAP, 2007). The same year, a group of 50 biomedical experts published their consensus statement for the clinical management of intersexuality (Lee et al., 2006). Insightful analyses on the politics of re-naming intersexuality as ‘disorders of sex development’ (DSD) by this group of experts are offered by Reis (2007), Machado (2008) and Holmes (2011), for which this work retains the use of ‘intersexuality’ and ‘intersex’ as the preferred terms.

Medical teams that are not guided by health policies, administrative mechanisms or the law to care for intersex persons rely heavily on clinical wisdom and published clinical recommendations, guidelines or consensus statements by biomedical experts. Today, the revised consensus statement for the management of intersexuality by thirty biomedical experts from the United States, France, Belgium, Canada, Italy, Sweden, Qatar, the United Kingdom, Morocco and Rotterdam (Mouriquand et al., 2016) stands as an important source that legally protects medical teams and medical institutions; even though it has been noted that such revision ignores human rights in intersex care (Feder and Dreger, 2016). Taken together, expert opinion with regard to intersex care in the United States is not harmonious.

Given the geopolitical landscape with regard to the clinical management of intersexuality around the globe, we surveyed the evolution of arguments outside the United States that champion the ethical and legal responsibilities of medical teams in the care of intersex persons and second, we studied the use of rhetoric by key policy stakeholders in the United States to champion or to bypass these responsibilities when caring for intersex persons as evidenced by the rhetorical use of language related to international standards of human rights.

Materials and methods

We studied the evolution of arguments that have been used to challenge current practices of intersex care since the publication of ‘Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders: International consensus conference on intersex’ (Lee et al., 2006). The revision of this Consensus was taken as the baseline state-of-knowledge with regard to intersex medical care in the United States (Mouriquand et al., 2016).

Documents for health policy analyses

The following list of documents is the representative of three different linguistic acts with regard to the clinical management of intersexuality. None of these are legally binding. Following critical geopolitical theory (O’Tuathai, 1996), timelines and places of origin were taken into consideration. Analysis of these documents aimed to contrast the rhetorical use of language to address human rights considerations in intersex care within and outside the United States.

Legislative resolution in the United Sates: (i) The Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 110, ‘Relative to sex characteristics’ of the California Legislative Council Bureau (September, 2018).

Human rights advocacy: (i) Heinrich Böll Foundation, Democracy Promotion and Human Rights (Human Rights between the Sexes: A preliminary study in the life of inter*individuals, 2013), (ii) The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (The Fundamental Rights Situation of Intersex People, 2015), (iii) Human Rights Watch and InterACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth (‘I want to be like Nature Made Me’: Medically Unnecessary Surgeries on Intersex Children in the US, 2017), (iv) The Darlington Statement (2017), (v) Reports presented to the Human Rights Council or to the Committee against Torture of the United Nations.

Clinical guidelines or recommendations by medical associations in the United States. (i) The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health and Wellness Group (American Academy of Pediatrics 2014); (ii) The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Adolescent Health Care (2016/2017); (iii) The American Medical Association, Board of Trustees (2018); (iv) a statement by three former Surgeon-General of the United States (2017) was included in this analysis.

Rhetorical criticism and mapping of key terms

The following key terms were surveyed in Resolution No.110 (2018): ‘sex’, ‘gender’, ‘sex/gender’, ‘psychological’, ‘physiological’, ‘human rights’, ‘harm’, ‘cosmetic’, ‘surgery’ or ‘operation’, ‘function’ and ‘disorders of sex development’ in singular, plural or gerund forms where applicable to study the weight given to sex/gender, medical/psychological or human rights considerations when arguing in favour of change of current clinical practices for intersex care. Following rhetorical criticism principles by Black (1978), these terms were also tracked to the other two types of documents; human rights advocacy and clinical guidelines or recommendations. The rationale behind this methodological approach was to determine whether there was a common or a distinct rhetorical ground in their arguments as defined by the relationship of each document with its audience, purpose, ethics, argument, evidence, arrangement, delivery and style.

Guidelines for psychological care

We aimed to determine whether initiatives by the American Psychological Association (APA) underscore human rights principles to champion intersex mental health. The rationale was that, in a broad level of understanding, support for psychological health has represented a common ground of opinion between health professionals and intersex persons. Guidelines by the APA addressing LGBTIQ mental health during the past 15 years were studied.

Results

Rather than referring to standards of care, health practitioners and key stakeholders in the United States often refer to consensus statements, recommendations or guidelines when addressing intersex care. Standards demand practitioners to follow a defined set of clinical algorithms and practices; statements and recommendations leave room for preferences and choices guided by clinical wisdom during decision-making processes, whereas guidelines, for the most part, provide principles to enhance best practices in the effecting of the profession. For the purposes of the following analysis that includes a critical revision of professional consensus statements, clinical recommendations, clinical guidelines, reports or studies, a legislative resolution and expert opinions (n = 21 documents), it is important to keep in mind that all of these types of documents are aspirational and that state and federal law in the United States can override them.

As seen in Table 1, the more recent consensus statement for intersex care during infancy no longer relies on the caliber of the phallus at birth to assign sex, a fact that was reiterated in recommendation number six by Mouriquand and collaborators (2016). Similarly, it was believed that tissues with lost reproductive capacity due to atypical sex development ought to be removed during sex reassignment surgery. This view has changed over the years as reflected in: recommendation number 2 (no removal of gonads in cases with non-functional androgen receptors), recommendation number 4 (no removal of embryological tissues that typically would have differentiated into female reproductive organs) and recommendation number 5 (no removal of gonads that have not fully differentiated into testicles following histological criteria). In alignment with, now widely, accepted opinions on the psychological impact of repeated and painful genital procedures on intersex children (Preves, 2003), the same group of experts also provided recommendation number 3, to avoid vaginal dilations.

Table 1.

Revision of clinical guidelines for the management of intersexuality in the USA.

| Clinical recommendations 10 years after The Consensus of Chicago |

|---|

|

If not surgically corrected shortly after birth, cloacal exstrophy is most likely incompatible with life. Recommendation deemphasises penile size. Verbatim text (Mouriquand et al., 2016).

Around the globe, self-identified intersex persons and persons who identify themselves as being born with genital variance share their life experiences through the internet and social media. Their voices have found a common resonance, albeit not exclusively, in the universal principles set forth by The Yogyakarta Principles (Alston et al., 2006, 2017).

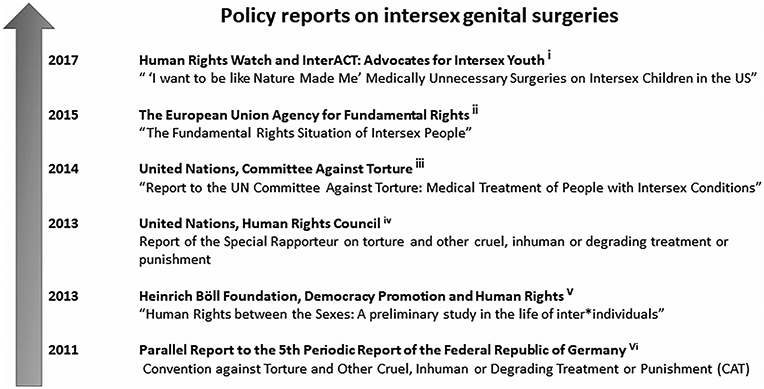

Figure 1 shows the timeline and sponsoring foundations or non-government organisations (NGOs) that have recently produced reports raising serious concerns about intersex medical care as well as reports presented to the Committee against Torture of the United Nations. The notions of bodily autonomy, free self-determination and body integrity have become key human rights concepts in these global discussions about intersex medical care.

Figure 1.

Policy reports during this decade that make reference to human rights principles to address intersex genital surgeries. i. This report includes verbatim statements of: (i) intersex people from California, New York, Massachusetts, Texas, Florida, Maryland, Illinois, Wisconsin and New Jersey, (ii) parents of intersex children from California, Florida, Texas, Iowa, Wisconsin, Massachusetts, and New York, and (iii) providers from seven undisclosed State of origin to meet their request of anonymity. ii. This report opines that their Member States ‘…should avoid non-consensual ‘sex-normalising’ medical treatments on intersex people.’ iii. Tamar-Mattis (2014). This report concludes that ‘Intersex people in the USA suffer significant harm as a result of genital-normalising surgery in childhood, involuntary sterilisation, excessive genital exams and medical display, human experimentation and denial of needed medical care. Such treatment constitutes a violation of human rights as recognised by multiple international bodies’ (p. 4). iv. Méndez (2013). As previously argued by Veith (2011), this report validates the use of the term ‘torture’ when referring to the practice of medical procedures that were not consent to by affected individuals. In reference to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex persons, ‘The Special Rapporteur calls upon all States to repeal any law allowing intrusive and irreversible treatments, including forced genital-normalising surgery, involuntary sterilisation, unethical experimentation, medical display, “reparative therapies” or “conversion therapies”, when enforced or administered without the free and informed consent of the person concerned. He also calls upon them to outlaw forced or coerced sterilisation in all circumstances and provides special protection to individuals belonging to marginalised groups’ (p. 23). v. Ghattas, (2013). This report examines human rights across countries for whom the author denominates ‘inter* individuals’ in Western/Central Europe, Eastern Europe/The Balkans, Africa, South America, Oceania and Asia. vi. Veith (2011). This report delineates several aspects of medical treatment of intersexuality in Germany as torture. Although the term is usually used in the context of interrogation, punishment or intimidation of a captive, the report expands this definition to include ‘medically unnecessary genital ‘normalising’ surgeries and hormone treatments that were not legally consented to by the patient’ (p. 16).

Emerging medical opinions in the United States with regard to intersex genital surgeries

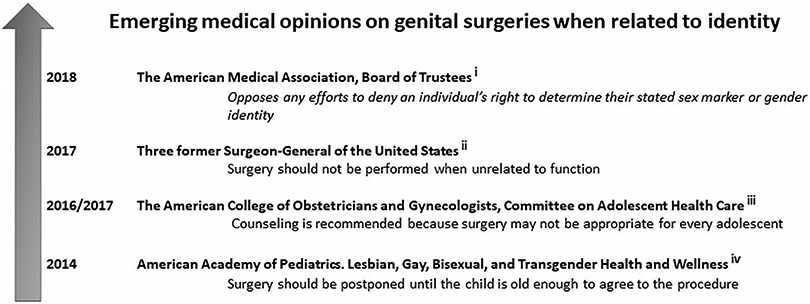

Figure 2 shows emergent medical opinion in the United States that proposes a deferral of intersex genital surgeries until the affected child is able to participate in medical decision processes. A concise, but powerful, 10-paragraph statement by 3 former Surgeon General of the United States makes a clear distinction between surgical procedures that aim to preserve function versus those that aim to change cosmetic appearance. Elders, Satcher, and Carmona (2017) are of the opinion that,

Figure 2.

Emerging medical opinions during this decade on genital surgeries when related to identity. i. Verbatim text. It refers to sex reassignment medical procedures for trans* individuals. ii. Elders, Statcher, & Carmona (2017). iii. Committee Opinion, Number 686, January 2017 is a revised version of Committee Opinion Number 662, May 2016. iv. This opinion by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness Committee was published 8 years after the retraction of the original clinical guideline by the American Academy of Pediatrics that recommended surgical intervention shortly after birth (AAP, 2000, 2007).

While we do not doubt that doctors who support and perform these surgeries have the best interests of patients and their parents at heart, our review of the available evidence has persuaded us that cosmetic infant genitoplasty is not justified absent a need to ensure physical functioning, and we hope that professionals and parents who face this difficult decision will heed the growing consensus that the practice should stop. (p. 2)

Their opinion is supported by three principles.

First, there is insufficient evidence that growing up with atypical genitalia leads to psychosocial distress. […] Second, while there is little evidence that cosmetic infant genitoplasty is necessary to reduce psychological damage, evidence does show that the surgery itself can cause severe and irreversible physical harm and emotional distress. […] Finally, these surgeries violate an individual’s right to personal autonomy over their own future. […] Those whose oath or conscience says ‘do no harm’ should heed the simple fact that, to date, research does not support the practice of cosmetic infant genitoplasty. (pp. 2–3)

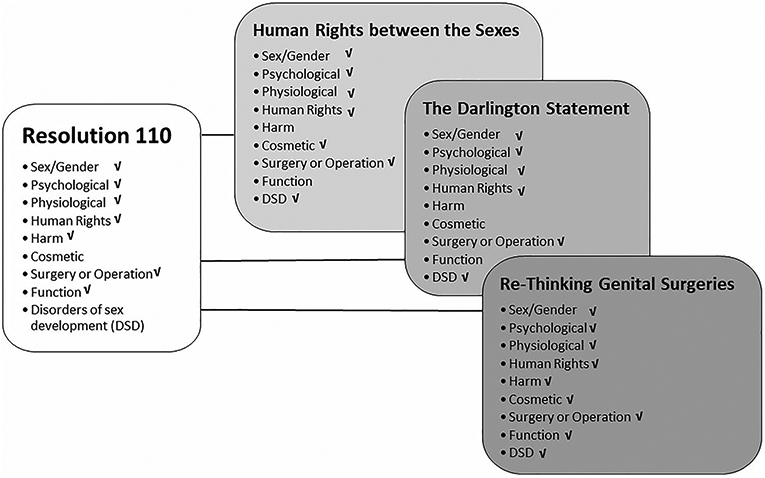

We noted that their use of the term ‘cosmetic infant genitoplasty’ was repeated six times in their 996-word statement. Therefore, we tracked the use of the terms ‘sex’, ‘gender’, ‘sex/gender’, ‘psychological’, ‘physiological’, ‘human rights’, ‘harm’, ‘cosmetic’, ‘surgery’ or ‘operation’, ‘function’ and ‘disorders of sex development’ in four types of documents with distinct targeted audiences (Black, 1978); namely, a legislative resolution in the United States, a study by a Germany-based international advocacy foundation, a statement by a group of NGOs and self-identified intersex persons in Australia and New Zealand, and the statement by these former Surgeon-General of the United States. Figure 3 shows some overlap in the use of selected key terms in these documents. Of significance, Resolution 110 did not use the term ‘disorders of sex development’ while The Darlington Statement made reference to the term only once to oppose its use. In addition, although Resolution 110 did not make reference to cosmesis, it refers to functional considerations when addressing genital surgeries. The statement by the three former Surgeon-General of the USA is the only one that makes reference to all tracked terms. To investigate further if the differential use of these terms reflects a shared or distinct rhetorical use of language to support change in current medical practices of intersex care, the following domains were assessed in these documents: audience, purpose, ethics, argument, evidence, arrangement, delivery and style following Black (1978). With regard to these domains, we found that the documents by the Germany-based international foundation and the one produced by NGOs and self-identified intersex individuals from Australia and New Zealand were more similar between them than the legislative resolution and the statement by medical experts in the United States (see Table 2). Therefore, these two documents outside the United States share a common rhetorical ground based on human rights principles and the law whereas this expert medical opinion in the United States made a succinct reference to personal autonomy without raising legal considerations.

Figure 3.

Content analysis of key terms. From left to right: Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 110 – Relative to sex characteristics; Ghattas, 2013; Darlington Statement: Joint consensus statement from the intersex community retreat in Darlington, March 2017; Elders, Statcher & Carmona, 2017. Shared use of the terms ‘sex’, ‘gender’, ‘sex/gender’, ‘psychological’, ‘physiological’, ‘human rights’, ‘surgery’ and ‘operation’ was noted across these documents.

Table 2.

Analysis of arguments that favours change of current standards of care for intersex people.

| Analytical Domains, Rhetorical Criticism | Legislative Resolution Senate of California United Sates1 | Study by Foundation, Germany2 with 30 international offices | Statement by Intersex Community Organizations and Individuals Australia and New Zealand3 | Statement by three Surgeon General United States4 |

| Audience | Stakeholders in the health professions | International; non-governmental organisations (NGOs) | Government stakeholders in Australia and New Zealand | Medical experts (as noted in paragraph 10) |

| Purpose | ‘This measure would, among other things, call upon stakeholders in the health professions to foster the well-being of children born with variations of sex characteristics through the enactment of policies and procedures that ensure individualised, multidisciplinary care, as provided.’ (Introductory statement) | ‘The aim of the study is to specify – and shed light upon – the largely invisible discrimination against intersex individuals.’ (Under ‘1. The aim and time frame of the preliminary study’, p. 11) | Under subheading ‘Health and well-being’, 13 specific calls for action are made and framed within human rights principles. The full document contains a total of 59 statements that recognises state-of-knowledge or calls for action | To re-think genital surgeries on intersex infants (paraphrased title by authors) |

| Ethics | Opposition to prejudice, bias, discrimination, commitment to safety and security, celebration of diversity | ‘ … to call attention to … violations of human rights against intersex individuals.’ (Under ‘Preface’, p.7) | To protect right to self-determination, to eliminate discrimination, stigmatisation and human rights violations, including harmful practices in medical settings. (Under ‘Preamble’) | ‘Do no harm’5 |

| Argument | ‘California should serve as a model of competent and ethical medical care and has a compelling interest in protecting the physical and psychological well-being of minors, including intersex youth…’ (last argument prior to resolutions 1–5) | ‘The study provides points of departure for strategies to improve the human rights situation of intersex individuals and recommends to actors how to develop measures in this area in order to render visible gender diversity as a means of enhancing human rights protection.’ (Under ‘Preface’, p.8) | ‘We note that intersex peer support remains largely unfunded, advocacy funding remains precarious and limited, and intersex-led organisations rely on volunteers to address the many gaps in services left by other, well-resourced health, social services and human rights institutions.’ (Under ‘E. Preamble’) | ‘The U.S. government is one of many that have recently raised questions about infant genitoplasty, cosmetic genital surgery meant to make an infant’s genitals ‘match’ the binary sex category they are assigned by adults entrusted with their care.’ (paragraph 2) |

| Evidence | Report by Human Rights Watch, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2013), The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2015), World Health Organization (2014), The Intersex and Genderqueer Recognition Project in the US, The United States Department of State, The AIS-DSD Support Group in the US, interACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth in the US, San Francisco Human Rights Commission (2005), opinion of a Stanford-educated Urologist and a young intersex San Francisco resident | Questionnaire that consisted of three parts (medical practices and procedures; legal situation [focusing on civil status]; and social situation [focusing on social visibility beyond medical discourses]) was sent to personal contacts, NGOs and offices of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in 24 countries of the global South and East as well as Europe. Sixteen questionnaires were returned from 12 countries (Australia, Belgium, Germany, France, New Zealand, Serbia, South Africa, Taiwan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine and Uruguay). Study results are shown | Data, individual and collective life experiences of intersex community organisations and individuals in New Zealand and Australia | Not specified. ‘…our review of the available evidence has persuaded us that cosmetic infant genitoplasty is not justified absent a need to ensure physical functioning …’ (paragraph 5) |

| Arrangement | 4 pages; Legislative resolution comprised of 25 arguments and 5 resolutions | 64 pages document; data depicted in 7 world maps and a table with raw data as an Annex. Study report divided in 8 sections: ‘Preface; Definition of inter*, intersex; The aim and time frame of the preliminary study; Methodology; Summary of findings; Recommendations for action for international actors; A description of countries; Annex’ | 8-pages with 7 subheadings: ‘Preamble; We acknowledge; Human rights and legal reform; Health and well-being; Peer support; Allies; Education, awareness & employment’. Photo and names of participants on the cover page | 4-pages document; cover page, 2 pages with text and 1 page with 6 footnotes |

| Delivery | Senate Concurrent Resolution – Sate of California | Study sponsored by Heinrich Böll Foundation, Volume 34 of the Publication Series on Democracy | Self-initiated joint statement by intersex community organisations and individuals in Australia and New Zealand | 10 paragraphs. Publication by Palm Center: Blueprints for Sound Public Policy |

| Style | Legal. Preamble to legislation | Advocacy. Academic research | Advocacy. Denouncement of injustice. Call for action to key stakeholders in various government institutions with emphasis to those related to advocacy funding, medicine, law and education | Expert opinion. Inclusive. E.g. ‘While we do not doubt that doctors who support and perform these surgeries have the best interests of patients and their parents at heart…’ (Paragraph 5) |

Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 110 – Relative to sex characteristics. Resolution Chapter 225 (11 September 2018).

The Darlington Statement: Joint consensus statement from the intersex community retreat in Darlington, March 2017.

Lat.: Primum non nocere or primum nil nocere. A close reference to this bioethical principle is found in the Hippocratic Corpus, Epidemics, Book I of the Hippocratic school: ‘Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient’. (Book I, Section 11, trad. Adams, gr.: ἀσκέειν, περὶ τὰ νουσήματα, δύο, ὠφελέειν, ἢ μὴ βλάπτειν).

Quotation marks denote verbatim text from referenced sources.

Guidelines for psychological care

We wanted to determine whether the APA underscores human rights principles in their guidelines to better support intersex health. We found that, in 2005, they created IPsyNet, International Psychology Network for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Issues to:

… facilitate and support the contributions of psychological organizations to the global understanding of human sexual and gender diversity, to the health and well-being of people around the world who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual or intersex (LGBTI), and to the full enjoyment of human rights by people of all sexual orientations, gender expressions, gender identities and sex characteristics. (¶.2)

One year later, they published Answers to Your Questions About Individuals with Intersex Conditions (APA, 2006). They asserted,

… that parents and care providers tell children with intersex conditions about their condition throughout their lives in an age-appropriate manner. Experienced mental health professionals can help parents decide what information is age-appropriate and how best to share it. People with intersex conditions and their families can also benefit from peer support. (p.2)

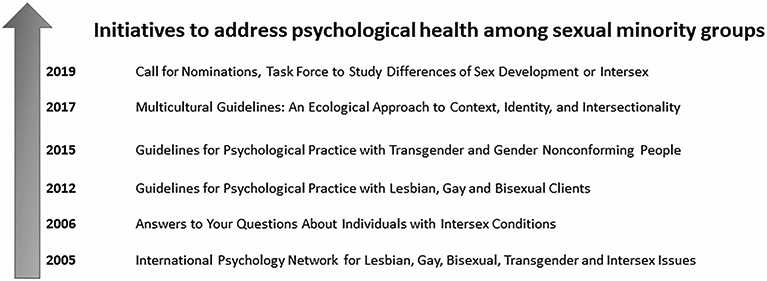

Although specific guidelines for psychological care of intersex individuals and their families by the APA are still lacking, the Association has produced Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Clients (2012) and Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People (2015). Reference to human rights is made once under ‘Appendix A – Internet Resources’ in the 2012 guidelines and once in the text in the 2015 guidelines. They also published the Multicultural Guidelines: An Ecological Approach to Context, Identity, and Intersectionality (2017). In this guideline, reference to intersex persons is made when referring to an LGBTQ+ collective. More recently, this Association (2019) announced a call for nominations to create the Task Force on Differences of Sex Development or Intersex, with the objective of producing a report with recommendations. While their use of the term ‘differences’ instead of ‘disorders’ accentuates a departure from typical clinical language, it remains to be seen whether this upcoming report or guideline will underscore human rights principles. Figure 4 presents the time course of these initiatives.

Figure 4.

Initiatives by the American Psychological Association (APA) to support intersex mental health. In 2019, the APA called for nominations to establish a task force aiming to address intersex mental health. Timelines of previous initiatives addressing sexual minority groups are shown.

Nevertheless, the group of experts who revised the original consensus statement of 2006 (Mouriquand et al., 2016) is of the opinion that,

There is general acknowledgement among experts that timing, the choice of the individual and irreversibility of surgical procedures are sources of concerns. There is, however, little evidence provided regarding the impact of non-treated DSD during childhood for the individual development, the parents, society and the risk of stigmatization. The low level of evidence should lead to design collaborative prospective studies involving all parties and using consensual protocols of evaluation. (p.140)

Discussion

We found that arguments to support the change of current practices of care for intersex people in the United States are unsettled when challenged with international standards of human rights. Although human rights principles have been referenced when arguing in favour of change, the rhetorical use of language privileges medical opinion rather than human rights enforced by law. At the moment, such opinion favours ‘evidence’ and ‘prospective collaborative studies’ (Mouriquand et al., 2016) before eliminating the clinical practice of intersex genital surgeries, which ignores human rights principles (Feder and Dreger, 2016). The withstanding clinical recommendation in the United States is to deploy intersex clinical treatments during infancy or early childhood. But unfortunately, the rights-based approach to guarantee intersex care in the United States has proven ineffective partly because state and federal policies and laws in this country do not match international and regional treaties on the rights to sexuality and sexual health (Miller, Gruskin, et al., 2015; Miller, Kismödi, et al., 2015) and the rights of children (Cohen et al., 2019; Ouellette, 2010).

The European Commission (2012) and the Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics (2012) privilege the rights of the child to take informed decisions when related to intersex care. More recently, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2015) has reiterated that age of consent to receive medical treatments and sterilisation is directly related to the intersections between human rights and the care of intersex children. For persons under the age of 18, the application of human rights standards to promote health follows a developmental framework where, as the child grows older, there is an evolution of the intellectual and emotional capacities to think, to act and to take decisions for oneself. In this context, the decisional powers of the child grow parallel to chronological age as the powers and responsibilities of parents and the state simultaneously decrease over the same time period. With the notable exception of the United States (Child Rights Campaign, 2018), 196 nations have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). A second salient issue directly related to the intersections between human rights and the care of intersex children is sterilisation; the removal of testis or ovaries during infancy with the idea of preventing cancer later in life. But as noted by the proponents of a new clinical algorithm to reach a specific diagnosis within the spectrum of intersex phenotypes (León et al 2019), evidence-based information on the risks of cancer carried by specific intersex diagnoses is still lacking. Although international interagency statements convened by the World Health Organization have called for the elimination of ‘forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilisation’ (World Health Organization, 2014), the United States has not ratified such position either. In the case of Germany, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2014) requested data collection on the frequency of genital surgeries and sterilisation of intersex children along with a plan to end these medical practices. Five years later, the German medical establishment stepped up to the plate and recently adopted a human rights framework in their revision of intersex care, whereby ‘[t]he personal right to self-determination has always to be protected’ (Krege et al., 2019).

A significant departure from the prevalent medical opinion in the United States is made by the 15th-, 16th- and 17th-Surgeon General of the United Sates (Elders et al., 2017). A recent change in one of the American Medical Association (AMA) bylaws with regard to Affirming the Medical Spectrum of Gender may reflect a plausible transition between two ends of the spectrum. In reference to transgender individuals, AMA used to ‘oppose any effort to prohibit the reassignment of an individual’s sex’, and now they ‘oppose any efforts to deny an individual’s right to determine their stated sex marker or gender identity’ (Resolution 005; AMA, 2018). Nevertheless, the California Urological Association (CUA) opposed to the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 110 – Relative to sex characteristics of the State of California (CUA, 2018). From a biomedical research standpoint, the National Institutes of Health of the USA have made significant efforts to fund research on human intersexuality. A multi-centre project aimed to bring biomedical researchers, bioethicists and patient advocates to the table, but this effort failed after key participants, in protest, left the group (Reardon, 2016).

Taking together, the opinions of intersex persons, international advocacy foundations and non-government organisations over the years demand that medical teams in the care of intersex persons in the United States meet their ethical and legal responsibilities within human rights principles. But the American medical establishment is far from meeting these international standards partly because these are not distinctively recognised in state, federal or constitutional law. In addition, we found that the use of rhetoric in the United States on the clinical management of intersexuality avoids human rights and legal considerations while conferring power to clinical wisdom. Such wisdom enforces an outdated definition of sex based on reproduction that ignores the politics of identity, sexuality and desire. In the United States, neoliberal political ideations and embedded cultural constructs that have long been fuelled by western religious thought find a common ground of opinion on what constitutes a righteous person as a (complete) male or a (complete) female with the entitlement to full citizenship and accompanying civil and human rights.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this work was published in abstract form; PRHSJ (2019) 38, 52. This text reflects part of the postdoctoral work by C.E.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alston P, Anmeghichean M, Cabral M, Cameron E, Correa SO, Erturk Y,… Wintemute R (2006). The Yogyakarta principles. Retrieved from http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/official-versions-pdf/. [Google Scholar]

- Alston P, Brands IK, Brown D, Cabral Grispan M, Cameron E, Carpenter M,… Zieselman K (2017). The Yogyakarta principles plus 10. Retrieved from http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/official-versions-pdf/. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2007). AAP Publications retired or Reaffirmed, October 2006. Pediatrics, 119, 405. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Genetics, Section on Endocrinology, Section on Urology. (2000). Evaluation of the newborn with developmental anomalies of the external genitalia. Pediatrics, 106, 138–142. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness. (2014). Explaining disorders of sex development & intersexuality. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health and wellness of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Retrieved from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/genitourinarytract/Pages/Explaining-Disorders-of-Sex-Development-Intersexuality.aspx.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Committee on Adolescent Health Care, Committee Opinion, Number 686. (2017, January). Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Adolescent-Health-Care/Breast-and-Labial-Surgery-in-Adolescents.

- American Medical Association. (2018). American Medical Association House of Delegates (I-18), Report of Reference Committee on Amendments to Constitution and Bylaws. Retrieved from https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2018-11/i18-refcomm-conby-report_0.pdf.

- American Psychological Association. (2005). About IPsyNet. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ipsynet/about.

- American Psychological Association. (2006). Answers to your questions about individuals with intersex conditions. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/sexuality/intersex.pdf.

- American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with Lesbian, gay and bisexual clients. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/amp-a0024659.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/transgender.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Call for nominations for the task force on differences of sex development or intersex. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/call.

- Black E (1978). Rhetorical criticism: A study in method. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- California Urological Association. (2018). RE: SCR 110, Relative to sex characteristics – OPPOSE. Retrieved from https://aacuweb.org/docs/news/2018-03-26_urologists-oppose-ca-scr110.aspx.

- Child Rights Campaign. (2018). Participating countries. Retrieved from http://www.childrightscampaign.org/what-is-the-crc/participating-countries.

- Cohen SS, Frye-Browers E, Bishop-Josef S, O’Neill MK, & Westphaln K (2019). Reframing child rights to effect policy change. Nursing Outlook, 67, 450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Darlington Statement: Joint Consensus Statement from the Intersex Community Retreat in Darlington, March 2017. Retrieved from https://oii.org.au/darlington-statement/ [Google Scholar]

- Elders MJ, Statcher D, & Carmona R (2017). Re-thinking genital surgeries on intersex infants. Retrieved from http://www.palmcenter.org/publication/rethinking-genital-surgeries-intersex-infants/. [Google Scholar]

- Erdman R (2015). Remarks at the UN Women Executive Board, by Richard Erdman, Senior Advisor and Acting ECOSOC Ambassador. New York: United States Mission to the United Nations. Retrieved from http://usun.state.gov/remarks/6831. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Justice. (2012). Trans and intersex people. Discrimination on the grounds of sex, gender identity, and gender expression. XX: XX. Retrieved from https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9b338479-c1b5-4d88-a1f8-a248a19466f1.

- The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2015). The fundamental rights situation of intersex people. Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/publication/2015/fundamental-rights-situation-intersex-people.

- Feder EK, & Dreger A (2016). Still ignoring human rights in intersex care. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 12, 436–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghattas DC (2013). Human rights between the sexes: A preliminary study in the life of inter*individuals. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Publication Series on Democracy, 34, 10. Retrieved from https://www.boell.de/sites/default/files/endf_human_rights_between_the_sexes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JA (2017). Legal. Ethical and human rights considerations for physicians treating children with atypical or ambiguous genitalia. Seminars in Perinatology, 41, 252–255. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen T, Hina Jilani KG, & Bustreo F (2017). Realisation of human rights to health and through health. Lancet, 389, 2087–2089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31359-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M (2011). The intersex enchiridion: Naming and knowledge. Somatechnics, 1, Retrieved from 10.3366/soma.2011.0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Commission of The City & County of San Francisco. (2005). A human rights investigation into the medical “normalization” of intersex people. Retrieved from https://ihra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/sfhrc_intersex_report.pdf.

- Human Rights Watch and InterACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth. (2017). I want to be like nature made me: Medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children in the US. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/07/25/i-want-be-nature-made-me/medically-unnecessary-surgeries-intersex-children-us.

- Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. (2015). Violence against LGBTI persons. XX: XX. Retrieved from http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/ViolenceLGBTIPersons.pdf.

- Krege S, Eckoldt F, Ritcher-Unruh A, Kohler B, Leuschner I, Mentzel H-J,… Richter-Appelt H (2019). Variations of sex development: The first German interdisciplinary consensus paper. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 15, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, & Hughes IA, in collaboration with the participants in the International Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (2006). Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders: International consensus conference on intersex. Pediatrics, 118, 488–500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León NY, Reyes AP, & Harley VR (2019). A clinical algorithm to diagnose differences of sex development. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinolology, 7, 560–574. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30339-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado PS (2008). Intersexualidade e o Consenso de “Chicago”: As vicissitudes da nomenclatura e suas implicações regulatórias. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 23, 109–124. doi: 10.1590/S0102-69092008000300008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Méndez JE (2013). UN Doc. A/HRC/22/53. [SRT 2013]. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Gruskin S, Cottingham J, & Kismödi KE (2015). Sound and Fury – engaging with the politics and the law of sexual rights. Reproductive Health Matters, 23(46), 7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, K., Cottingham E, & Gruskin S,J (2015). Sexual rights as human rights: A guide to authoritative sources and principles for applying human rights to sexuality and sexual health. Reproductive Health Matters, 23, 16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouriquand PD, Gorduza DB, Gay CL, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Baker L, Baskin LS,… Lee P (2016). Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how? Journal of Pediatric Urology, 12, 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Tuathai G (1996). Critical geopolitics. The politics of writing global space. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette A (2010). Shaping parental authority over children’s bodies. Indiana Law Journal (indianapolis, ind, 85, 955–1002. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol85/iss3/5. [Google Scholar]

- Preves S (2003). Intersex and identity: The contested self. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S (2016). Stuck in the middle. Nature, 533, 160–164. doi: 10.1038/533160a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis E (2007). Divergence or disorder? The politics of naming intersex. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 50, 535–543. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2007.0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 110 – Relative to Sex Characteristics. (2018). Resolution Chapter 225. (11 September 2018). State of California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved from https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SCR110. [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Govender M, & Mills EJ (2007). Do human rights matter to health? Lancet, 370, 521–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61236-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics. (2012). On the management of differences of sex development: Ethical issues relating to “intersexuality.” opinion No. 20/2012. Retrieved from https://www.ilgaeurope.org/sites/default/files/swiss_ethics_council_ccl_2012.pdf.

- Tamar-Mattis A (2014). Report to the UN Committee against torture: medical treatment of people with intersex conditions. Advocates for informed choice. Retrieved from https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CAT/Shared%20Documents/USA/INT_CAT_CSS_USA_18525_E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2014). List of issues in relation to the initial report of Germany. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/779629.

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989). Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/uk/4aa76b319.pdf

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. [Google Scholar]

- Veith LG (2011). Parallel report to the 5th periodic report of the Federal Republic of Germany on the convention against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (CAT). Retrieved from http://intersex.shadowreport.org/post/2011/08/20/Shadow-Report-CAT-2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization. An interagency statement. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/eliminating-forced-sterilization/en/. [Google Scholar]