Abstract

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder with unclear mechanisms. While hypersensitivity to angiotensin II via vasoconstrictive angiotensin type-1 receptor (AT1R) is observed in preeclampsia, the importance of vasodilatory angiotensin type-2 receptor (AT2R) in the control of vascular dysfunction is less clear. We assessed whether AT1R, AT2R, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression are altered in placental vessels of preeclamptic women and tested if ex vivo incubation with AT2R agonist Compound 21 (C21; 1 μM) could restore AT1R, AT2R, and eNOS balance. Further, using a rat model of gestational hypertension induced by elevated testosterone, we examined whether C21 (1 μg/kg/day, oral) could preserve AT1R and AT2R balance and improve blood pressure, uterine artery blood flow, and vascular function. Western blots revealed that AT1R protein level was higher while AT2R and eNOS protein were reduced in preeclamptic placental vessels, and AT2R agonist C21 decreased AT1R and increased AT2R and eNOS protein levels in preeclamptic vessels. In testosterone dams, blood pressure was higher, and uterine artery blood flow was reduced, and C21 treatment reversed these levels similar to those in controls dams. C21 attenuated the exaggerated Ang II contraction and improved endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in uterine arteries of testosterone dams. These C21-mediated vascular effects were associated with decreased AT1R and increased AT2R and eNOS protein levels. C21 also increased serum nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin production in testosterone dams and attenuated the fetoplacental growth restriction. Thus, AT1R upregulation and AT2R downregulation are observed in preeclampsia and testosterone model, and increasing AT2R activity could help restore AT1R and AT2R balance and improve gestational vascular function.

Keywords: angiotensin, AT2 receptors, pregnancy, preeclampsia, vascular function, endothelium, blood flow, fetus, testosterone

AT1R/AT2R balance is tilted toward vasoconstrictive AT1R in preeclampsia; restoring this balance using AT2R agonist mitigates vascular dysfunction in hypertensive pregnant rats, providing a new approach in managing gestational vascular dysfunction.

Introduction

A successful pregnancy requires major hemodynamic adaptations in the mother to meet the metabolic needs of the fetus. Pregnancy-associated hemodynamics changes include increased plasma volume and cardiac output, decreased vascular resistance and blood pressure, and a 20-fold increase in uterine artery (UA) blood flow [1–5]. Preeclampsia (PE) is a major disorder affecting about 5–8% of pregnancies in the United States and 8 million pregnancies worldwide and accounts for 50, 000–60, 000 deaths per year globally [6–9]. PE is characterized by endothelial dysfunction with decreased expression and activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [10–12]. Clinically, PE is presented with maternal hypertension and may be associated with intrauterine growth restriction, leading to long-term programming of adult-onset cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [13–19].

Although PE poses serious consequences to the health of mother and fetus, the mechanisms involved are unclear. A growing body of evidence supports a role for the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in the pathogenesis of PE. One of the major effectors of the RAS is angiotensin II (Ang II). Ang II activates Ang II type-1 receptor (AT1R) and type-2 receptor (AT2R). AT1R is mainly expressed in vascular smooth muscle and induces vasoconstriction, whereas AT2R is predominately expressed in endothelial cells and induces vascular relaxation through the release of vasodilator substances such as nitric oxide (NO) and bradykinin [20–22]. Enhanced AT1R-mediated hypersensitivity to Ang II is proposed to play a role in PE pathogenesis. For example, AT1R is upregulated in PE [23], and PE women exhibit enhanced vascular contractile sensitivity to Ang II [24–26]. In fact, the hypersensitivity to Ang II is shown to persist for several years, even after delivery [24]. In addition, genetic polymorphism of AT1R, 1166C, is shown to be associated with an increased risk of PE [27]. Because of the difficulty to perform mechanistic studies in pregnant women, we utilize animal models of PE. Others and we have shown that exposure of pregnant rats to elevated testosterone (T), at levels similar to that observed in PE women, recapitulates the PE phenotype. The T-exposed pregnant rat exhibits hypertension, exaggerated vascular contractile responses to Ang II, proteinuria, endothelial dysfunction, decreased spiral artery elongation, placental hypoxia, and fetal growth restriction [27–33]. Studies have shown that T-exposed pregnant rats exhibit increased expression of AT1R in the mesenteric arteries and UA, and treatment with an AT1R antagonist decreases blood pressure, suggesting a role for AT1R in gestational hypertension [33, 34]. However, the reduced blood pressure in T dams treated with AT1R antagonist can also be explained by the possibility that most Ang II would be directed toward AT2R to promote vasodilation.

We have recently shown that Ang II-induced vasoconstriction is reduced and that AT2R expression and AT2R-mediated vasodilation and blood flow are enhanced in the UA of normal pregnant rats [35]. Total knockout of AT2R in mice induced late-pregnancy hypertension [36], and AT2R blockade decreased UA blood flow [35], emphasizing the role of AT2R in blood pressure and UA blood flow regulation during normal pregnancy. However, the direct effect of activating the vasodilator AT2R in controlling blood pressure and UA blood flow during gestational hypertension is not clear. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that activation of AT2R is an important mechanism to restore blood pressure and UA blood flow in gestational hypertension. First, we determined whether AT1R upregulation and AT2R and eNOS downregulation are observed in placental vessels isolated from PE women and if enhancing AT2R activity restores AT1R and AT2R balance and increases eNOS expression. Then, we used the T-exposed pregnant rat model to determine whether enhancing AT2R activity reverses the increase in blood pressure, promotes UA blood flow, and reduces vascular dysfunction. The effects of AT2R activation on plasma nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin levels were also measured. Finally, the impact of AT2R activation on placental and fetal weights was examined.

Materials and methods

Isolation of chorionic plate vessels from the placenta of control and PE women

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The tissue collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UnityPoint Health-Meriter Hospital (Madison, WI) and the Health Sciences Institutional Review Boards of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Protocol#2017-0975). All subjects gave written, informed consent. The obstetricians at the UnityPoint Health-Meriter Hospital Birth Center diagnosed patients with uncomplicated and PE pregnancies. PE was defined according to the standard American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists criteria [37]: systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mmHg on two occasions at least 4 h apart after 20 weeks of gestation in a woman with previously normal blood pressure. The other criterion is a protein/creatinine ratio greater than or equal to 0.3. Placenta was collected immediately after deliveries from uncomplicated and PE pregnancies (n = 6 each; Table 1). All patients are Caucasian due to the local demographic distribution. Small arterial branches of the maternal side chorionic plate arteries (100–200 μm diameter) were identified under a stereomicroscope and carefully dissected free from the surrounding connective tissue within 30 min of delivery. The vessels were cut into rings of 2 mm length and incubated with and without an AT2R agonist Compound 21 (C21, 1 μM) for 24 h in a culture dish containing phenol red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in 37°C humidified incubators. Following treatment, vessels were processed for Western blotting for AT1R, AT2R, and eNOS quantification.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of normal pregnant women and patients with PEa

| Variable | Control | PE |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 25.4 ± 3 | 26.1 ± 2.4 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.6 ± 0.6 | 37.6 ± 0.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 115.3 ± 3.4 | 145.4 ± 5.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 71.7 ± 6.7 | 90.8 ± 5.1 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3457 ± 461 | 3134 ± 549 |

| Fetal sex (male/female) | 3/3 | 4/2 |

aAll patients are Caucasians and without current or history of other major complications.

Animals

All animal studies were carried out as per National Institutes of Health guidelines (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) with approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (IACUC protocol#V005847). Timed-pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats were purchased from Envigo Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and were maintained on 12L/12D cycles in a temperature-controlled room (23°C) and provided with food and water ad libitum. On day 15 of pregnancy, rats were divided into two groups with n = 12 in each group. The control group received sesame oil (vehicle) subcutaneously, and the treatment group received T propionate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) (0.5 mg/kg) subcutaneously from day 15 to 20 of gestation, as previously described [32, 34, 38]. This dose and duration of T propionate were selected to mimic the pattern and increases in T levels as in PE pregnancies [33, 39, 40]. A subset of control (n = 6) and T-treated dams (n = 6) were gavaged with AT2R agonist compound 21 (C21, VicorePharma, GÖteborg, Sweden; 1 mg/kg/day) [41] from day 15 to day 20 of gestation. C21 has 4000-fold higher selectivity to AT2R than AT1R [42], and this dose of C21 is shown to effectively activate AT2R without affecting AT1R [41, 43, 44]. On gestation day (GD) 20, blood pressure and UA blood flow were measured. Then, rats were sacrificed with CO2 asphyxiation, and blood and UA were isolated. Placental and fetal weights were also recorded. A portion of the UA was used for vascular reactivity studies, and the remaining was used for measuring mRNA and protein expression of AT1R, AT2R, and eNOS. The placenta was used to measure hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α protein expression. Serum was used to measure bradykinin and nitrate/nitrite levels.

Blood pressure

Mean blood pressure was recorded using a computerized noninvasive CODA system (Kent Scientific, Litchfield, CT, USA) as in our previous studies [45, 46]. Rats were acclimatized for 2 days in a pre-warmed plexiglass restrainer for 15 min, and then blood pressure was measured the following day. An occlusion cuff and a volume pressure-recording cuff were applied to the base of the tail. The cuff was programmed to inflate and deflate automatically within 90 s. Average results obtained from the last 5 cycles were taken as the individual mean blood pressure for that rat. All recordings and data analyses were done using Kent Scientific Software.

Uteroplacental blood flow

A noninvasive high-resolution pulsed-wave Doppler ultrasonography was performed using Vevo 2100 Imaging System (FUJIFILM VisualSonics Inc. Toronto, ON, Canada) as described in our previous studies [35, 39]. In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in dorsal recumbency with paws on electrode gel on a heated monitoring platform (FUJIFILM VisualSonics Inc.). Body temperature, heart rate, electrocardiogram traces, and respiration rates were controlled all the time. The eye cream was used to prevent dry eyes. The abdominal fur was clipped and then completely removed by applying a depilatory cream. Pre-warmed ultrasound gel was applied, and Doppler ultrasonography was performed using a 30-MHz transducer (FUJIFILM VisualSonics Inc.). Anatomical structures were visualized using B-Mode, and UA blood flow was traced by using Color Doppler Mode. Blood flow through vessels was quantified by Pulse-Wave Doppler mode. Peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end-diastolic velocity (EDV), the area under the peak velocity-time curve, and R-R interval were measured from three consecutive cardiac cycles, and the results were averaged. The angle between the ultrasound probe and the flow direction was kept at less than 50° (33° on average) during the velocity waveform recordings. All measurements and analyses were performed using Vevo LAB software (v.1.7, FUJIFILM VisualSonics Inc.) by researchers blinded to the experimental groups. Mean velocity (MV) over the cardiac cycle was calculated by dividing the area under the peak velocity-time curve by the R-R interval. Blood flow velocity distribution was determined using the following formula: F = 1/2 MVπ (D/2)2 (where MV = mean peak velocity over the cardiac cycle [cm/s], D = diameter [cm], and F = blood flow [mL/min]). UA resistance index (RI = [PSV – EDV]/PSV) and pulsatility index (PI = [PSV – EDV]/MV) were calculated to quantify the pulsatility of blood velocity waveforms.

Ex vivo vascular reactivity studies

The uterine horn was removed by laparotomy, and the tissue was placed directly into ice-cold Krebs buffer (in mM: NaCl, 119; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.17; NaHCO3, 25; KH2PO4, 1.18; EDTA, 0.026; and d-glucose, 5.5; pH 7.4). Under a dissecting microscope, the main UA was identified and dissected free from fat and connective tissue at the midpoint of the uterine arcade. Arteries were cut into 1.5 mm segments, and two 25 μm wires were inserted through the lumen. One wire was attached to stationary support driven by a micrometer, while the other was attached to an isometric force transducer (Multi Myograph, Model 610 M Danish Myo Technologies, Aarhus, Denmark). The myograph organ bath (6 mL) was filled with Krebs buffer maintained at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2–5% CO2. The vessels were washed and incubated for 30 min under zero force before normalization (Powerlab, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO) [47, 48]. The vessels were allowed to equilibrate for 1 h, and the arterial preparations were exposed to 80 mM KCl until reproducible and maximal depolarization-induced contractions were achieved. The presence or absence of intact endothelium was confirmed by observing the relaxation response to 1 μM acetylcholine (ACh, Sigma) in rings precontracted with 1 μM phenylephrine (PE, Sigma), as described previously [34, 35]. After washing, vascular contractile responses to cumulative additions Ang II (10−11 to 3 × 10−8 M) were determined in endothelium-denuded UA. Since tachyphylaxis develops to repeated Ang II cumulative dose-response curves, only one dose-response curve was obtained per tissue [47]. Endothelium-dependent relaxation was assessed with ACh (10−9–10−5 M) induced relaxation in PE-precontracted endothelium-intact arteries. A submaximal PE concentration was used for precontraction. Endothelium-independent relaxation was determined with sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (10−9–10−6 M) induced relaxation in PE-precontracted endothelium-denuded arteries.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) was used to isolate total RNA from human and rat tissues as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration and integrity were determined using the DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix, Wilmington, DE, USA), and cDNA synthesis was done with 1 μg of total RNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After reverse transcription, cDNA was diluted and amplified using FAM (Invitrogen) as the fluorophore in a CFX96 real-time thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). TaqMan assays were carried out in 10 μl volumes for real-time PCR (RT-PCR) at a final concentration of 250 nM TaqMan probe and 900 nM of each primer. PCR conditions for TaqMan Gene Expression Assay were 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C for one cycle, then 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C for 50 cycles. Assays for rat (AT2R-Rn00560677_s1, AT1R-Rn02758772_s1, eNOS-Rn02132634_s1, β-actin-Rn00667869_ m1) and human (AT2R-Hs02621316_s1, AT1R-Hs00258938_m1, eNOS-Hs01574659_m1, β-actin-Hs01060665_ g1) were obtained by Assay-on-Demand (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Scientific). Results were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method and expressed in fold change of the gene of interest in treated versus control samples. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and β-actin was used as an internal control.

Western blotting

Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) containing a protease inhibitor tablet and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail-2 and -3 (Sigma) and kept on ice for 20–30 min with intermittent tapping for proper lysis. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14 000g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by a BCA assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Loading samples were prepared by mixing 40 μg proteins with NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer and reducing agent (Invitrogen; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein bands were resolved on 4%–12% gradient NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 100 V for 2–3 h at room temperature alongside negative control and Precision Plus Standard (Kaleidoscope; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After separation on the gel, proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) at 20 V for 1 h. The membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried milk for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with respective primary antibodies against AT1R (ab124505; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), AT2R (ab92445; Abcam), eNOS (cst32027; Cell Signaling Technology), HIF1α (cst14179; Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (cst4970; Cell Signaling Technology). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h and then developed using the Pierce ECL detection kits (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The densitometric analysis was done using ImageJ software. Results are expressed as ratios of the intensity of a specific band to that of β-actin.

Nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin measurement

Serum levels of nitrate/nitrite (NOx) (780001; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) and bradykinin (ADI-900-206; Enzo Life Sciences AG, Basel, Switzerland) were determined as per the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM with “n” representing the number of patients/rats per group. Data analysis was done using GraphPad Prism for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For vascular reactivity experiments, cumulative concentration-response curves were analyzed by computer fitting to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve. Contraction responses to Ang II were calculated as a percent of its maximal contraction and as a percent of 80 mM KCl contraction. Relaxant responses to ACh were calculated as percent inhibition of the PE-induced contraction. Emax (maximal responses) and pD2 (negative log molar concentration that produces 50% effect) values were determined by regression analysis. Two-way analysis of variance tests were conducted, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. Differences are considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

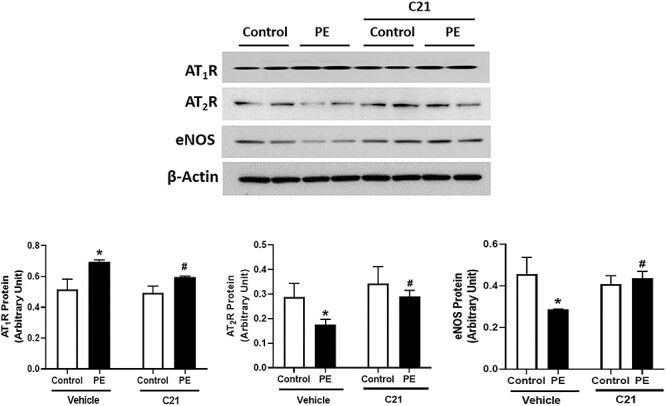

Ang II receptors and eNOS protein levels in PE placental vessels

Western blots revealed that AT1R protein level was increased while AT2R protein was reduced in placental vessels isolated from PE women versus controls (Figure 1; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). Also, the eNOS protein level was significantly decreased in placental vessels from PE women versus controls (Figure 1; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Figure 1.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on Ang II receptor and eNOS expression in placental vessels isolated from control and PE women. Placental vessels were incubated with and without AT2R agonist C21 (1 μM) for 24 h in phenol red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum and then processed for protein quantification. Representative Western blots for AT1R, AT2R, eNOS, and β-actin are shown at top; blot density obtained by densitometric analysis normalized to β-actin is shown at bottom. Values are means ± SEM of six patients per group. *P ≤ 0.05 versus Vehicle control. #P ≤ 0.05 versus PE without C21.

Ex vivo application of AT2R agonist C21 to control vessels did not alter AT1R, AT2R, and eNOS protein levels compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 1; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). Application of C21 to PE vessels significantly decreased AT1R protein but increased AT2R and eNOS protein levels compared with vehicle-treated PE vessels (Figure 1; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Blood pressure and UA blood flow in pregnant rats

We next examined the in vivo effect of AT2R agonist C21 on blood pressure and UA blood flow using a rat model of T-exposure. Blood pressure was higher, and AT2R agonist C21 reduced blood pressure in T dams (Figure 2A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 did not alter blood pressure in the control group (Figure 2A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Figure 2.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on mean arterial pressure and UA blood flow, resistance, and pulsatility index in control and T dams. On GD 20, (A) mean arterial pressure and (B) UA blood flow, resistance index, and pulsatility index were measured using noninvasive CODA system and Doppler ultrasound, respectively, in control and T dams with and without C21 treatment. Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group. *P ≤ 0.05 versus Vehicle control. #P ≤ 0.05 versus T without C21.

UA blood flow was significantly reduced, but the resistance and pulsatility indices were significantly increased in T dams compared to controls (Figure 2B; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). Administration of C21 abrogated the T-induced decrease in UA blood flow and normalized resistance and pulsatility indices. C21 had no significant effect on UA blood flow, resistance index, and pulsatility index in control dams (Figure 2B; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Vasoconstrictor response

We then assessed Ang II receptor-induced vasoconstriction in ex vivo studies in control and T dams with and without C21 treatment. Ang II-induced contractile responses in endothelium-denuded UA were greater with increased sensitivity and maximal response in T dams than controls (Figure 3 and Table 2; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). Administration of C21 attenuated the T-induced exaggerated Ang II contraction with a decrease in sensitivity and maximal response (Figure 3 and Table 2; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 did not affect Ang II vasoconstriction in controls (Figure 3 and Table 2; n = 6).

Figure 3.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on Ang II-mediated vascular contraction in endothelium-denuded UA from control and T dams. On GD 20, UA rings were isolated from control and T dams with and without C21 administration, and the vascular contractile responses to cumulative addition of Ang II were determined. Ang II contraction was presented as percent of maximal contraction (top panel) and as percent of contraction induced by 80 mM KCl (bottom panel). Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group.

Table 2.

Vascular function in control and T dams

| Variable | Control | Control+C21 | T | T + C21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang II pD2 | 8.69 ± 0.039 | 8.66 ± 0.032 | 9.05 ± 0.064* | 8.76 ± 0.020# |

| Ang II Emax | 120.45 ± 4.203 | 111.62 ± 3.917 | 133.43 ± 4.241* | 120.61 ± 5.161# |

| Ach pD2 | 6.27 ± 0.156 | 6.43 ± 0.166 | 5.342 ± 0.169* | 6.12 ± 0.208# |

| Ach Emax | 96.848 ± 1.194 | 97.208 ± 0.086 | 57.30 ± 5.080* | 87.665 ± 3.798# |

| SNP pD2 | 7.697 ± 0.075 | 7.714 ± 0.036 | 7.748 ± 0.047 | 7.645 ± 0.599 |

| SNP Emax | 97.253 ± 1.723 | 99.167 ± 0.833 | 99.231 ± 0.769 | 98.75 ± 1.125 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 10–12 mesenteric arterial rings from six rats in each group. pD2 is presented as –log [mol/L] and Emax is presented as percent of maximal contraction or relaxation. All abbreviations are defined in the text.

* P ≤ 0.05 compared to control group.

# P ≤ 0.05 compared to T without C21.

Vascular contractile responses to KCl (80 mM), a determination of depolarization-induced contraction, was similar in T and control dams (Figure 4; n = 6). C21 treatment caused no significant alteration in the KCl-induced contraction in T and control dams (Figure 4; n = 6).

Figure 4.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on depolarization-induced vascular contractile responses to KCl in control and T dams. On GD 20, endothelium-denuded UA rings were isolated from control and T dams with and without C21 administration, and the vascular contraction to 80 mM KCI was determined. Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group.

Vasodilator response

ACh-induced relaxation was significantly reduced in endothelium-intact UA with a decrease in ACh sensitivity and maximal response in T dams than in controls (Figure 5A and Table 2; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 treatment restored the decrease in ACh relaxation in T dams by increasing ACh sensitivity and maximal relaxation (Figure 5A and Table 2; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 did not alter ACh-induced relaxation in control dams Figure 5A and Table 2; n = 6).

Figure 5.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on vascular relaxation in the UA from control and T dams. On gestational day 20, UA rings were isolated from control and T dams with and without C21 administration. UA rings were precontracted with phenylephrine (PE) and (A) endothelium-dependent acetylcholine (ACh)-induced relaxation and (B) endothelium-independent sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced relaxation was measured. Values are given as means ± SEM of 6 rats per group.

To test the responsiveness of vascular smooth muscle to vasodilators, the NO donor SNP was used. SNP caused concentration-dependent relaxation and was equally potent in inducing relaxation in control and T dams with and without C21 treatment (Figure 5B and Table 2; n = 6).

Ang II receptors and eNOS protein levels

At the mRNA level, rodents possess two AT1R receptor isoforms, designated as AT1aR and AT1bR. AT1aR has a dominant expression in blood vessels with a significant role in blood pressure regulation, whereas the role of AT1bR is not well known [49, 50]. AT1aR mRNA was higher, while AT2R and eNOS mRNA were reduced in UA of T dams compared to controls (Figure 6A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). There was no difference in AT1bR mRNA expression between control and T dams (data not shown). C21 treatment restored the T-induced changes in Ang II receptor expression by decreasing AT1aR and increasing AT2R mRNA expression (Figure 6A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). Also, C21 increased eNOS mRNA expression in T dams. C21 did not affect AT1aR, AT2R, and eNOS mRNA expression in controls (Figure 6A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on Ang II receptor and eNOS expression in UA from control and T dams. On GD 20, UA was isolated from control and T dams with and without C21 administration and processed for (A) quantitative RT-PCR analysis for mRNA and (B) Western blotting for protein expression of AT1R, AT2R, and eNOS. Representative blots for AT1R, AT2R, eNOS, and β-actin are shown on the top and normalized densitometric analysis are shown at the bottom. Both mRNA and protein expression were normalized to β-actin. Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group. *P ≤ 0.05 versus Vehicle control. #P ≤ 0.05 versus T without C21.

As shown in Figure 6B, Western blotting showed that AT1R protein levels were significantly increased, and AT2R and eNOS protein levels were significantly decreased in T dams compared to controls (Figure 6B; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 treatment decreased AT1R protein levels and increased AT2R and eNOS protein levels in T dams but did not affect in controls (Figure 6B; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Serum nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin levels

To investigate the effect of AT2R activation on the release of endogenous vasodilators, serum levels of nitrate/nitrite (a proxy measure of NO production) and bradykinin were examined. As shown in Figure 7A and B, serum nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin levels were significantly decreased in T dams compared to controls (P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 treatment restored the T-mediated decrease in serum nitrate/nitrite and bradykinin levels, but these levels were not altered in control dams (Figure 7A and B; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Figure 7.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on serum bradykinin and nitrate levels in control and T dams. On GD 20, blood serum was isolated through cardiac puncture following CO2 inhalation from control and T dams with and without C21 administration. (A) NOx and (B) bradykinin levels were determined using enzyme immunoassay. Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group. *P ≤ 0.05 versus Vehicle control. #P ≤ 0.05 versus T without C21.

Placental HIF1α expression and placental and fetal weight

We next determined the effect of AT2R stimulation on HIF1α expression (a proxy measure of placental perfusion) and placental and fetal biometrics. Western blotting revealed increased placental HIF1α protein levels in the T dams compared to controls (Figure 8A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 treatment decreased HIF1α levels in T dams but did not affect HIF1α levels in control dams (Figure 8A; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6).

Figure 8.

Effect of AT2R agonist C21 on placental hypoxia and fetal and placental weights in control and T dams with and without C21 administration. On GD 20, (A) HIF1α protein expression was determined in the placenta. Representative Western blots of HIF1α and β-actin are shown on the top and blot densities obtained by densitometric values normalized to β-actin are shown at the bottom. (B) Fetal weight and (C) placental weight were also measured. Placental and fetal weights in each dam were averaged, and each dot represents the mean data per dam/litter. Values are means ± SEM of six rats per group. *P ≤ 0.05 versus Vehicle control. #P ≤ 0.05 versus T without C21.

As shown in Figure 8B and C, elevated maternal T resulted in placental and fetal growth restriction. C21 significantly attenuated T-mediated effects by restoring placental and fetal weight (Figure 8B and C; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 did not impact the placental and fetal weights in controls (Figure 8B and C; P ≤ 0.05; n = 6). C21 treatment did not alter litter size in control and T dams (data not shown).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are as follows: (1) AT1R expression was increased, and AT2R and eNOS expression were reduced in placental vessels isolated from PE women, and ex vivo incubation with AT2R agonist C21 restored balance by decreasing AT1R and increasing in AT2R and eNOS levels in PE vessels, (2) in an in vivo rat model of gestational hypertension, administration of AT2R agonist C21 abolished hypertension and enhanced UA blood flow by attenuating Ang II-mediated vascular contraction and increasing endothelium-dependent relaxation to levels comparable to those in control pregnant rats, (3) the C21-mediated suppression of Ang II contractile responses in hypertensive dams was related with increased AT2R and decreased AT1R levels, (4) the enhanced endothelium-dependent vasodilation in C21 administered hypertensive dams was associated with increased eNOS expression, NO production, and serum bradykinin levels, and (5) C21 ameliorated placental hypoxia and improved fetoplacental growth in hypertensive dams, which could possibly be due to improved vasodilation and enhanced UA blood flow.

PE is manifested as hypertension and often intrauterine growth restriction [9, 51]. There is an urgent need to develop safe, effective, and targeted therapies for PE to reduce maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Evidence in humans indicates that RAS is activated during PE with exaggerated vascular sensitivity to Ang II [52–55]. Ang II activates AT1R to cause vasoconstriction and AT2R to cause vasodilation [56–59]. Our findings of increased AT1R and decreased AT2R levels in the placental vessels suggest that Ang II receptor balance is tilted toward vasocontractile effect as most of the Ang II would be directed toward AT1R. These data are different from reports that AT1R is similar and AT2R increases in PE women versus control pregnancies [52]. The differences may be related to regional differences (uterus [52] vs. the present isolated placental chorionic plate arteries) or the method of measuring Ang II receptors (mRNA expression [52] vs. the present protein levels). However, our finding is in agreement with the report that immunohistochemical localization of AT1R is higher than AT2R in the blood vessels of placental villi of PE women [60]. Based on the finding of increased levels of vasocontractile AT1R in the placental vasculature of PE women, it is logical to rationalize that Ang II hypersensitivity could be prevented by using AT1R antagonists. Since AT1R antagonists are contraindicated in pregnancy [61–63], direct activation of AT2R could be an alternative strategy. Our observations that ex vivo incubation of PE placental vessels with AT2R agonist C21 restored Ang II receptor balance by decreasing AT1R and increasing AT2R protein levels, support this premise. C21 also restored the decrease in eNOS protein levels in PE vessels, suggesting that AT2R activation could also improve endothelial function.

We evaluated the in vivo pressor and vascular effects of C21 using the pregnant rat model of T exposure. The pregnant rats with elevated T exhibited increased blood pressure and decreased UA blood flow, consistent with previous reports [64–66]. The increase in blood pressure in T dams was associated with exaggerated vasoconstriction to Ang II, similar to the Ang II hyperreactivity reported in PE women [26, 54, 55, 67, 68]. In the present study, administration of AT2R agonist C21 to T dams abolished the hypertensive response, improved UA blood flow, and reversed the exaggerated vasoconstriction to Ang II to levels similar to those in control pregnant rats, providing evidence for a role for AT2R activation in restoring hemodynamics and vascular function in gestational hypertension. The response to KCl, which causes contraction due to membrane depolarization, was not different with and without C21 treatment in endothelium-denuded UA, suggesting that the attenuated Ang II vasoconstriction in T + C21 dams is more likely related to Ang II receptor changes and not due to generalized nonreceptor-mediated changes like altered hypertrophy or hyperplasia of vascular smooth muscle cells. Further, the attenuated Ang II contractions in T + C21 dams are noted in endothelium-denuded UA; this suggests that the subdued Ang II contractions in T + C21 dams are related to decreased arterial sensitivity to Ang II rather than to the confounding effects of the endothelium. In support of this, the uterine arteries from T dams exhibited increased AT1R mRNA and protein levels and decreased AT2R mRNA and protein levels, and C21 treatment reversed the balance of angiotensin receptors in uterine arteries of T dams. Thus, the reduced blood pressure and UA resistance index in T dams treated with C21 can be explained by the possibility that most Ang II would be directed toward AT2R to promote vasodilation.

It was interesting to note that C21 treatment upregulated AT2R expression. This increase occurred at the mRNA level, suggesting that AT2R activation can increase transcription of its own receptor, similar to previous reports [69, 70]. In addition, AT2R activation also downregulated AT1R expression, suggesting a complex cross-regulatory mechanism between the AT2R and AT1R. Several lines of evidence support this notion. It was reported that AT1R expression was significantly higher in AT2R knockout mice than in controls [71]. Overexpression and activation of AT2R downregulated AT1R expression in rat vascular smooth muscle cells through the activation of bradykinin/NO pathway [72]. Moreover, the transfection of the AT2R gene in rat vascular smooth muscle cells inhibited AT1R-mediated signaling [73]. Since C21 restored Ang II receptor balance ex vivo in PE vessels, this suggests that the C21 effect on AT2R transcription could be direct, not secondary to changes in endocrine factors. The exact mechanism of how AT2R activation regulates its own transcription and extents control over AT1R expression needs to be investigated in future studies.

To examine the impact of C21 on endothelial function, we examined the endothelium-dependent relaxation response to ACh. ACh induced less relaxation in UA of T dams, indicating that endothelium-dependent control of vascular tone is compromised in T dams, consistent with the previous report [34]. The findings that C21 treatment potentiated ACh-induced relaxation in UA from T dams but had minimal effects in control dams suggests that the vascular relaxation responses to ACh have been preserved in T + C21 dams. Vascular relaxation to the NO donor SNP was not different in T + C21 versus T dams, suggesting that the differences are not related to smooth muscle vasodilating capability but likely related to endothelial function. Consistently, C21 has been shown to improve endothelium-dependent NO-mediated relaxations in the mesenteric arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats [74]. These results indicate that AT2R activation could improve NO synthesis by endothelial cells. This concept is reinforced with the observation that eNOS mRNA and protein levels were augmented in the UA, and nitrate/nitrite production was enhanced in the serum of T + C21 dams. It is not clear how C21 triggers eNOS expression, but C21 could directly stimulate eNOS expression in the endothelial cells based on the previous reports of C21 increasing eNOS expression in cultured cardiomyocytes via the calcineurin/NF-AT pathway [75]. AT2R activation also increased bradykinin production, consistent with the report in mice [21]. Since bradykinin is known to induce vasodilation through increased NO, prostacyclin, and EDHF production, the improvement in vasodilation and UA blood flow in T + C21 dams could also be secondary to the increase in bradykinin levels [20, 76, 77]. Taken together, these findings support a role for AT2R activation in preserving the endothelium-dependent vasodilation in T dams.

The present study shows that the placentas from T dams have higher expression of HIF1α. Since HIF1α is a key transcription factor responding to low oxygen, the increased HIF1α levels suggest that the placenta may be underperfused and hypoxic in T dams, consistent with the observation of decreased UA blood flow. C21 treatment effectively decreased HIF1α expression and partially improved placental and fetal weights in T dams, indicating that C21-mediated improvement in UA blood flow and placental perfusion and oxygenation could have contributed to the beneficial effect in T dams.

In conclusion, upregulation of AT1R and downregulation of AT2R may explain the increased blood pressure and Ang II hypersensitivity in PE pregnancies. Activation of AT2R, using pharmacological agonist, restored Ang II receptor balance and reinstated optimal blood pressure and UA blood flow with attenuated Ang II vasoconstriction, enhanced endothelial-mediated relaxation, and improved fetoplacental growth in T model of gestational hypertension. The present data should be interpreted with caution, as there are forms of gestational hypertension and PE that may not be adequately represented by the T model. Also, this study demonstrates only the preventive effect of C21 in the rat model; it would be interesting to examine in the future the potential effect of C21 in reversing PE-like characteristics. Nevertheless, the results suggest that increasing AT2R activity, using pharmacological agonists or genetic manipulation, may represent a novel approach in managing PE and long-term fetal health.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any potential or actual conflicts of interest with respect to the work reported in the article.

References

- 1. Sanghavi M, Rutherford JD. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation 2014; 130:1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chapman AB, Abraham WT, Zamudio S, Coffin C, Merouani A, Young D, Johnson A, Osorio F, Goldberg C, Moore LG, Dahms T, Schrier RW. Temporal relationships between hormonal and hemodynamic changes in early human pregnancy. Kidney Int 1998; 54:2056–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Browne VA, Julian CG, Toledo-Jaldin L, Cioffi-Ragan D, Vargas E, Moore LG. Uterine artery blood flow, fetal hypoxia and fetal growth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 2015; 370:20140068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osol G, Cipolla M. Pregnancy-induced changes in the three-dimensional mechanical properties of pressurized rat uteroplacental (radial) arteries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168:268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palmer SK, Zamudio S, Coffin C, Parker S, Stamm E, Moore LG. Quantitative estimation of human uterine artery blood flow and pelvic blood flow redistribution in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 80:1000–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Health OW. The World Health Report 2005 - Make Every Mother and Child Count. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2010; 376:631–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tan J, Yang M, Liao Y, Qi Y, Ren Y, Liu C, Huang S, Thabane L, Liu X, Sun X. Development and validation of a prediction model on severe maternal outcomes among pregnant women with pre-eclampsia: a 10-year cohort study. Sci Rep 2020; 10:15590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R, Ayoubi JM. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2011; 7:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaheen G, Jahan S, Ain QU, Ullah A, Afsar T, Almajwal A, Alam I, Razak S. Placental endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and role of oxidative stress in susceptibility to preeclampsia in Pakistani women. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020; 8:e1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Du L, He F, Kuang L, Tang W, Li Y, Chen D. eNOS/iNOS and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in the placentas of patients with preeclampsia. J Hum Hypertens 2017; 31:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhavina K, Radhika J, Pandian SS. VEGF and eNOS expression in umbilical cord from pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disorder with different severity. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:982159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMillen IC, Robinson JS. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: prediction, plasticity, and programming. Physiol Rev 2005; 85:571–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bateson P, Barker D, Clutton-Brock T, Deb D, D'Udine B, Foley RA, Gluckman P, Godfrey K, Kirkwood T, Lahr MM, McNamara J, Metcalfe NB et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature 2004; 430:419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lane SL, Doyle AS, Bales ES, Lorca RA, Julian CG, Moore LG. Increased uterine artery blood flow in hypoxic murine pregnancy is not sufficient to prevent fetal growth restriction. Biol Reprod 2020; 102:660–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cotechini T, Komisarenko M, Sperou A, Macdonald-Goodfellow S, Adams MA, Graham CH. Inflammation in rat pregnancy inhibits spiral artery remodeling leading to fetal growth restriction and features of preeclampsia. J Exp Med 2014; 211:165–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson CM, Lopez F, Zhang HY, Pavlish K, Benoit JN. Reduced uteroplacental perfusion alters uterine arcuate artery function in the pregnant Sprague-Dawley rat. Biol Reprod 2005; 72:762–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Konje JC, Howarth ES, Kaufmann P, Taylor DJ. Longitudinal quantification of uterine artery blood volume flow changes during gestation in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. BJOG 2003; 110:301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carey RM, Jin X, Wang Z, Siragy HM. Nitric oxide: a physiological mediator of the type 2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor. Acta Physiol Scand 2000; 168:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsutsumi Y, Matsubara H, Masaki H, Kurihara H, Murasawa S, Takai S, Miyazaki M, Nozawa Y, Ozono R, Nakagawa K, Miwa T, Kawada N et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor overexpression activates the vascular kinin system and causes vasodilation. J Clin Invest 1999; 104:925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gohlke P, Pees C, Unger T. AT2 receptor stimulation increases aortic cyclic GMP in SHRSP by a kinin-dependent mechanism. Hypertension 1998; 31:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leung PS, Tsai SJ, Wallukat G, Leung TN, Lau TK. The upregulation of angiotensin II receptor AT(1) in human preeclamptic placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001; 184:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saxena AR, Karumanchi SA, Brown NJ, Royle CM, McElrath TF, Seely EW. Increased sensitivity to angiotensin II is present postpartum in women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy. Hypertension 2010; 55:1239–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, Lindschau C, Horstkamp B, Jupner A, Baur E, Nissen E, Vetter K, Neichel D, Dudenhausen JW, Haller H et al. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest 1999; 103:945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gant NF, Daley GL, Chand S, Whalley PJ, PC MD. A study of angiotensin II pressor response throughout primigravid pregnancy. J Clin Invest 1973; 52:2682–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nalogowska-Glosnicka K, Lacka BI, Zychma MJ, Grzeszczak W, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Poreba R, Michalski B, Kniazewski B, Rzempoluch J, Group PIHS . Angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene A1166C polymorphism is associated with the increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Med Sci Monit 2000; 6:523–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gopalakrishnan K, Mishra JS, Chinnathambi V, Vincent KL, Patrikeev I, Motamedi M, Saade GR, Hankins GD, Sathishkumar K. Elevated testosterone reduces uterine blood flow, spiral artery elongation, and placental oxygenation in pregnant rats. Hypertension 2016; 67:630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sathishkumar K, Elkins R, Chinnathambi V, Gao H, Hankins GD, Yallampalli C. Prenatal testosterone-induced fetal growth restriction is associated with down-regulation of rat placental amino acid transport. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2011; 9:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sathishkumar K, Elkins R, Yallampalli U, Balakrishnan M, Yallampalli C. Fetal programming of adult hypertension in female rat offspring exposed to androgens in utero. Early Hum Dev 2011; 87:407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chinnathambi V, Selvanesan BC, Vincent KL, Saade GR, Hankins GD, Yallampalli C, Sathishkumar K. Elevated testosterone levels during rat pregnancy cause hypersensitivity to angiotensin II and attenuation of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in uterine arteries. Hypertension 2014; 64:405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chinnathambi V, Balakrishnan M, Ramadoss J, Yallampalli C, Sathishkumar K. Testosterone alters maternal vascular adaptations: role of the endothelial NO system. Hypertension 2013; 61:647–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chinnathambi V, More AS, Hankins GD, Yallampalli C, Sathishkumar K. Gestational exposure to elevated testosterone levels induces hypertension via heightened vascular angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling in rats. Biol Reprod 2014; 91:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chinnathambi V, Blesson CS, Vincent KL, Saade GR, Hankins GD, Yallampalli C, Sathishkumar K. Elevated testosterone levels during rat pregnancy cause hypersensitivity to angiotensin II and attenuation of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in uterine arteries. Hypertension 2014; 64:405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mishra JS, Gopalakrishnan K, Kumar S. Pregnancy upregulates angiotensin type 2 receptor expression and increases blood flow in uterine arteries of rats. Biol Reprod 2018; 99:1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mirabito KM, Hilliard LM, Wei Z, Tikellis C, Widdop RE, Vinh A, Denton KM. Role of inflammation and the angiotensin type 2 receptor in the regulation of arterial pressure during pregnancy in mice. Hypertension 2014; 64:626–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. American College of Obstetricians, Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy . Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 122:1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mishra JS, Blesson CS, Kumar S. Testosterone decreases placental mitochondrial content and cellular bioenergetics. Biology (Basel) 2020; 9: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gopalakrishnan K, Mishra JS, Chinnathambi V, Vincent KL, Patrikeev I, Motamedi M, Saade GR, Hankins GD, Sathishkumar K. Elevated testosterone reduces uterine blood flow, spiral artery elongation, and placental oxygenation in pregnant rats. Hypertension 2016; 67:630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sathishkumar K, Elkins R, Chinnathambi V, Gao H, Hankins GD, Yallampalli C. Prenatal testosterone-induced fetal growth restriction is associated with down-regulation of rat placental amino acid transport. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2011; 9:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ali Q, Patel S, Hussain T. Angiotensin AT2 receptor agonist prevents salt-sensitive hypertension in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol 2015; 308:F1379–F1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bosnyak S, Jones ES, Christopoulos A, Aguilar MI, Thomas WG, Widdop RE. Relative affinity of angiotensin peptides and novel ligands at AT1 and AT2 receptors. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011; 121:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carey RM, Howell NL, Jin XH, Siragy HM. Angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated hypotension in angiotensin type-1 receptor-blocked rats. Hypertension 2001; 38:1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ali Q, Wu Y, Hussain T. Chronic AT2 receptor activation increases renal ACE2 activity, attenuates AT1 receptor function and blood pressure in obese Zucker rats. Kidney Int 2013; 84:931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mishra JS, Hankins GD, Kumar S. Testosterone downregulates angiotensin II type-2 receptor via androgen receptor-mediated ERK1/2 MAP kinase pathway in rat aorta. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst 2016; 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sathishkumar K, Elkins R, Yallampalli U, Yallampalli C. Protein restriction during pregnancy induces hypertension in adult female rat offspring--influence of oestradiol. Br J Nutr 2012; 107:665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hannan RE, Davis EA, Widdop RE. Functional role of angiotensin II AT2 receptor in modulation of AT1 receptor-mediated contraction in rat uterine artery: involvement of bradykinin and nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 140:987–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mulvany MJ, Aalkjaer C. Structure and function of small arteries. Physiol Rev 1990; 70:921–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nguyen MJ, Hashitani H, Lang RJ. Angiotensin receptor-1A knockout leads to hydronephrosis not associated with a loss of pyeloureteric peristalsis in the mouse renal pelvis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2016; 43:535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo DF, Sun YL, Hamet P, Inagami T. The angiotensin II type 1 receptor and receptor-associated proteins. Cell Res 2001; 11:165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension 2005; 46:1243–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Anton L, Merrill DC, Neves LA, Diz DI, Corthorn J, Valdes G, Stovall K, Gallagher PE, Moorefield C, Gruver C, Brosnihan KB. The uterine placental bed renin-angiotensin system in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Endocrinology 2009; 150:4316–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Langer B, Grima M, Coquard C, Bader AM, Schlaeder G, Imbs JL. Plasma active renin, angiotensin I, and angiotensin II during pregnancy and in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 91:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stanhewicz AE, Jandu S, Santhanam L, Alexander LM. Increased angiotensin II sensitivity contributes to microvascular dysfunction in women who have had preeclampsia. Hypertension 2017; 70:382–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shah DM. The role of RAS in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep 2006; 8:144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Danyel LA, Schmerler P, Paulis L, Unger T, Steckelings UM. Impact of AT2-receptor stimulation on vascular biology, kidney function, and blood pressure. Integr Blood Press Control 2013; 6:153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Akazawa H, Yano M, Yabumoto C, Kudo-Sakamoto Y, Komuro I. Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor-induced cell signaling. Curr Pharm Des 2013; 19:2988–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Savoia C, D'Agostino M, Lauri F, Volpe M. Angiotensin type 2 receptor in hypertensive cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2011; 20:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Guthrie GP Jr. Angiotensin receptors: physiology and pharmacology. Clin Cardiol 1995; 18:III 29–III 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Judson JP, Nadarajah VD, Bong YC, Subramaniam K, Sivalingam N. A preliminary finding: immunohistochemical localisation and distribution of placental angiotensin II receptor subtypes in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. Med J Malaysia 2006; 61:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Buawangpong N, Teekachunhatean S, Koonrungsesomboon N. Adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with first-trimester exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2020; 8:e00644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wegleiter K, Waltner-Romen M, Trawoeger R, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Griesmaier E. Long-term consequences of fetal angiotensin II receptor antagonist exposure. Case Rep Pediatr 2018; 2018:5412138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moretti ME, Caprara D, Drehuta I, Yeung E, Cheung S, Federico L, Koren G. The fetal safety of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. Obstet Gynecol Int 2012; 2012:658310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gatford KL, Andraweera PH, Roberts CT, Care AS. Animal models of preeclampsia: causes, consequences, and interventions. Hypertension 2020; 75:1363–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Marshall SA, Hannan NJ, Jelinic M, Nguyen TPH, Girling JE, Parry LJ. Animal models of preeclampsia: translational failings and why. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys 2018; 314:R499–R508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cushen SC, Goulopoulou S. New models of pregnancy-associated hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2017; 30:1053–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Irani RA, Xia Y. Renin angiotensin signaling in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Semin Nephrol 2011; 31:47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gant NF, Worley RJ, Everett RB, MacDonald PC. Control of vascular responsiveness during human pregnancy. Kidney Int 1980; 18:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Matavelli LC, Huang J, Siragy HM, Angiotensin AT. (2) receptor stimulation inhibits early renal inflammation in renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 2011; 57:308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shibata K, Makino I, Shibaguchi H, Niwa M, Katsuragi T, Furukawa T. Up-regulation of angiotensin type 2 receptor mRNA by angiotensin II in rat cortical cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 239:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tanaka M, Tsuchida S, Imai T, Fujii N, Miyazaki H, Ichiki T, Naruse M, Inagami T. Vascular response to angiotensin II is exaggerated through an upregulation of AT1 receptor in AT2 knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999; 258:194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jin XQ, Fukuda N, Su JZ, Lai YM, Suzuki R, Tahira Y, Takagi H, Ikeda Y, Kanmatsuse K, Miyazaki H. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor gene transfer downregulates angiotensin II type 1a receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 2002; 39:1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Horiuchi M, Hayashida W, Akishita M, Tamura K, Daviet L, Lehtonen JY, Dzau VJ. Stimulation of different subtypes of angiotensin II receptors, AT1 and AT2 receptors, regulates STAT activation by negative crosstalk. Circ Res 1999; 84:876–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rehman A, Leibowitz A, Yamamoto N, Rautureau Y, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Angiotensin type 2 receptor agonist compound 21 reduces vascular injury and myocardial fibrosis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2012; 59:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Brede M, Roell W, Ritter O, Wiesmann F, Jahns R, Haase A, Fleischmann BK, Hein L. Cardiac hypertrophy is associated with decreased eNOS expression in angiotensin AT2 receptor-deficient mice. Hypertension 2003; 42:1177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yayama K, Okamoto H. Angiotensin II-induced vasodilation via type 2 receptor: role of bradykinin and nitric oxide. Int Immunopharmacol 2008; 8:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Carey RM, Jin XH, Siragy HM. Role of the angiotensin AT2 receptor in blood pressure regulation and therapeutic implications. Am J Hypertens 2001; 14:98S–102S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]