Abstract

A rapid phenotypic screening method for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) thymidine kinase (TK) genes was developed for monitoring acyclovir-resistant viruses. This method determines the biochemical phenotype of the TK polypeptide, which is synthesized in vitro from viral DNA using a procedure as follows. The TK gene of each sample virus strain is amplified and isolated under the control of a T7 promoter by PCR. The PCR products are transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase and translated in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. Using this method, enzymatic characteristics and the size of the TK polypeptides encoding HSV and VZV DNA were defined in less than 2 days without virus isolation. The assay should be a powerful tool in monitoring drug-resistant viruses, especially in cases in which virus isolation is difficult.

Acyclovir (ACV) possesses potent and selective antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and has been widely used in the treatment and prophylaxis of HSV and VZV infections. In addition to describing safe and effective ACV treatment, published case reports have described the isolation of ACV-resistant (ACVr) viruses, predominantly from immunocompromised patients and, in only five cases, from immunocompetent individuals (14, 23, 24, 32, 38, 39). Since the virus-encoded thymidine kinase (TK) and DNA polymerase are the specific targets of ACV, the ACVr phenotype of HSV and VZV is related to one of following mechanisms: (i) deficiency in viral TK activity or a low level of TK polypeptide expression (TK−; approximately 95 to 96% of ACVr HSV), (ii) a TK polypeptide with altered substrate specificity (TKA; 4 to 5% of ACVr HSV isolates) (5, 12, 23, 27), or (iii) viral DNA polymerase with altered substrate specificity in rare cases (4, 25, 28).

Most ACVr mutants show decreased neurovirulence due to their deficient or low TK activity and cause self-limited infections in patients with normal immunity (10, 26). However, infection with ACVr mutants can result in locally progressive mucocutaneous lesions in immunocompromised patients, becoming a source of severe pain and bacterial superinfection. In these cases, switching the antiviral therapy to foscarnet, which does not require phosphorylation by viral TK, is necessary, although side effects are frequently observed in patients receiving foscarnet (29). Therefore, the phenotypic screening of the virus in skin lesions has become increasingly important when choosing the appropriate therapy, especially in the case of patients who have a risk factor(s) for ACVr viral infection, such as immunodeficiency and long duration of ACV treatment (9, 23).

As standard methods, the plaque reduction assay and plaque autoradiography have been employed to estimate drug sensitivity and the phenotype of TK activity for HSV and VZV isolates. These assays take a long time, usually 1 or 2 weeks for characterization of HSV or VZV, respectively, although they possess several merits, such as the ability to identify the characteristic of each virion in a sample containing mixed virus populations and to set the standard criteria for virus phenotyping (5, 13, 41). Therefore, we developed and here describe a novel rapid method based on PCR for phenotypic characterization of HSV and VZV TK genes in less than 2 days.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human embryo lung (HEL) fibroblasts and Vero cells were cultivated in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum (MEM-CS10). The KOS and KOSdlsactk strains of HSV type 1 (HSV-1) and the 186 strain of HSV-2 were generously provided by D. M. Coen, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass., and by Y. Nishiyama, Nagoya University School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan, respectively. The SC16, SC16 S1, DM21, BW-S, BW-R, and 11334 strains of HSV-1 and the 8702, 8708, 8713, 11571, 11572, 11575, 11785, and 4365-9 strains of HSV-2 were kindly supplied by J. Hill, Glaxo Wellcome Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C. The KH52, KH54, and WT51 strains of HSV-1 isolated from Japanese patients with herpetic skin lesion were supplied by H. Machida, Yamasa Co., Choshi, Japan. The VRTK−, TAS, and TAR strains of HSV-1, the UWTK− strain of HSV-2, and the YS and YSR strains of VZV were isolated by our group (2, 30, 33, 36). The characteristics of these strains and the original papers describing these strains are summarized in Table 1. Each strain was grown in HEL fibroblasts and stored at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of virus strains used in this study

| Strain | IC50 (μg/ml) for:

|

TK

|

Isolation | Reference(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACVa | PAAa | Activityb | Mutationc | Sized | Phenotype | |||

| HSV-1 | ||||||||

| VR-3 | 0.088 | 19.5 | 11.8 | 376 | WT | 36, 37 | ||

| VRTK− | >100 | 52.1 | 1.6 | R281Stop | 280 | TK− | In vitro from the VR-3 | 36, 37 |

| KOS | 0.012 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 376 | WT | |||

| KOSdlsactk | >100 | 23.3 | 1.3 | 4-bp del. at codon 149 and 150 | 180 | TK− | In vitro from the KOS | 3 |

| SC16 | 0.10 | 7.7 | 13.0 | 376 | WT | |||

| SC16 S1 | 46.1 | 19.8 | 3.1 | C336Y | 376 | TKA | In vitro from the SC16 | 6 |

| DM21 | >100 | 35.7 | 1.2 | 816-bp del. | TK− | In vitro from the SC16 | 7 | |

| TAS | 0.089 | 10.5 | 12.7 | 376 | WT | 2, 31 | ||

| TAR | >100 | 11.4 | 1.3 | One-nucleotide del. at codon 355 | 407 | TK− | In an immunodeficient child from the TAS | 31 |

| BW-S | 0.14 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 376 | WT | 34 | ||

| BW-R | 35.3 | 13.4 | 1.8 | One-nucleotide ins. at codon 185 | 227 | TK− | In an immunodeficient child from the BW-S | 34 |

| KH52 | 0.056 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 376 | WT | 17 | ||

| KH54 | 0.042 | 9.0 | 13.4 | 376 | WT | 17 | ||

| WT51 | 0.052 | 28.4 | 11.9 | 376 | WT | 17 | ||

| 11334 | >100 | 15.3 | 0.9 | One-nucleotide del. at codon 146 | 181 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 12 |

| HSV-2 | ||||||||

| UW268 | 0.67 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 375 | WT | 36, 37 | ||

| UWTK− | 56.2 | 14.2 | 1.1 | One-nucleotide ins. at codon 186 | 228 | TK− | In vitro from the 286 | 36, 37 |

| 186 | 0.43 | 23.5 | 5.8 | 376 | WT | |||

| 8702 | 0.67 | 19.7 | 7.7 | 376 | WT | From an AIDS patient | 8 | |

| 8708 | 55.0 | 24.1 | NT | R223H | 376 | TKA | From an AIDS patient | 8 |

| 8713 | >100 | 13.5 | 1.3 | One-nucleotide del. at codon 73 | 85 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 8 |

| 11571 | >100 | 21.7 | 1.2 | One-nucleotide ins. at codon 266 | 390 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 12 |

| 11572 | >100 | 27.7 | 1.0 | D274G | 376 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 12 |

| 11575 | >100 | 27.4 | NT | One-nucleotide ins. at codon 186 | 228 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 12 |

| 11785 | 32.8 | 25.4 | 1.4 | N78D, R223H | 376 | TK− | From an AIDS patient | 12 |

| 4365-9 | 66.4 | 27.6 | 6.8 | N78D, L140F, R177W, R220K | 375 | TKA | From a healthy adult | 14 |

| VZV | ||||||||

| YS | 0.65 | 7.0 | 64.6 | 341 | WT | 15, 33 | ||

| YSR | 13.5 | 4.7 | 1.2 | One-nucleotide del. at codon 164 | 170 | TK− | In vitro from the YS | 15, 33 |

| Cell (HEL) | 74.1 | 48.2 | 1.0 | |||||

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ACV and phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) was determined by a plaque reduction assay on HEL fibroblasts.

Thymidine kinase activity in mock- or virus-infected HEL fibroblasts at 8 h postinfection was measured and expressed as fmol/cell/min.

The mutation sites of the BW-R, 11334, 11571, 11572, 11575, and 11785 were determined in this study, and other data are cited from previous reports which listed in the “Reference(s)” column.

Predicted size of the TK polypeptides from the nucleotide sequence of the TK gene were expressed as the number of amino acids.

Plaque reduction assay.

The susceptibility of viruses to ACV and phosphonoacetic acid was assayed with a 50% plaque reduction assay in HEL fibroblasts as described previously (16).

PCR.

The TK genes of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV, under the control of a T7 promoter, were prepared by PCR using primer sets T7-HSV1-TK and HSV1-TK-Dw, T7-HSV2-TK and HSV2-TK-Dw, and T7-VZV-TK and VZV-TK-Dw, respectively (Fig. 1). PCR was performed with 100 μl of reaction mixture containing 1 μl of the sample DNA, which corresponded to approximately 10 infected cells, using an Expand Hi-Fi PCR system (Roche Molecular Systems). Initial denaturation was at 94°C for 2 min followed by 10 cycles of denaturation (20 s at 94°C), annealing (2 min at 58°C for the HSV TK gene or at 60°C for the VZV TK gene), and extension (1 min 20 s at 72°C), and then 20 cycles of denaturing, annealing, and extension (1 min 20 s plus 5 s/cycle extension at 72°C) with an additional 20 min at 72°C after the last cycle. The PCR products were purified and dissolved in 30 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, with a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and stored at −20°C.

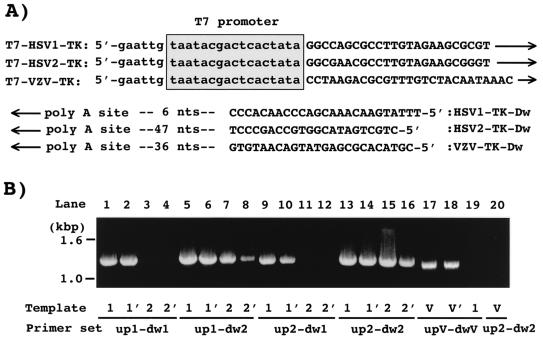

FIG. 1.

(A) Sequences of primers used in this study. (B) Primer specificities in PCR for TK genes of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV. Genomic DNA of the VR-3 (1) and TAS (1′) strains of HSV-1, the UW-268 (2) and 4365-9 (2′) strains of HSV-2, and the YS (V) and YSR (V′) strains of VZV were used in the PCR as template DNA. Abbreviations: up1, T7-HSV1-TK; dw1, HSV1-TK-Dw; up2, T7-HSV2-TK; dw2, HSV2-TK-Dw; upV, T7-VZV-TK; dwV, VZV-TK-Dw.

In vitro translation.

TK polypeptides of the HSV and VZV strains were synthesized directly from TK genes amplified with PCR using a Single Tube Protein System 3 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 50 to 100 ng of PCR products dissolved in 1 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, were mixed with 4 μl of transcription mixture and incubated at 30°C for 15 min. One microliter of the transcribed samples was mixed with 3 μl of the translation mixture (rabbit reticulocyte extracts) and 1 μl of 125 μM methionine or 8 μCi of [35S]methionine (>1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd.), and the entire mixture was incubated at 37°C for 60 min.

TK assay.

The samples of HSV-infected cells were obtained as follows. Confluent HEL fibroblast monolayers in 24-well tissue culture plates were either mock infected or infected with HSV at a multiplicity of infection of 1. After incubation for 8 h, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed once with MEM, and suspended in 0.2 ml of 200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. The cells were disrupted by sonication, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

TK activity was determined by previously described methods with some modifications (35). The reaction mixture in a total volume of 10 μl containing 1 or 0.1 μM thymidine, 0.1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (70 to 86 Ci/mmol), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, and 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was incubated at 37°C for 20 or 90 min for TK samples prepared from infected cells or by in vitro translation, respectively.

Fluorography.

The molecular weights of the TK polypeptides translated in vitro with [35S]methionine were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. After electrophoresis of the samples on 12% polyacrylamide gels, the polypeptides were fixed by immersing the gels in a 45% ethanol–10% acetic acid solution, and then the gels were processed for fluorography with En3 Hance (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, dried, and exposed to X-ray films for 2 days at −80°C.

RESULTS

Design of a phenotypic screening method for herpesvirus TKs.

To establish a novel screening method based on PCR and in vitro translation, primer sets for amplifying the TK genes of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV under the control of a T7 promoter were designed (Fig. 1A). In each primer for the upstream region of the TK gene, nucleotide sequences of the T7 promoter and the immediately upstream region of the TK gene were designed with six additional nucleotides at the 5′ site. The other primers were targeted to the downstream region of the poly(A) signal for the TK gene.

The specificity of the primers was estimated under the PCR conditions described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1B). With PCR using T7-HSV1-TK and HSV1-TK-Dw (lanes 1 to 4) or T7-HSV2-TK and HSV1-TK-Dw (lanes 9 to 12), a specific DNA fragment of 1,273 bp from HSV-1 DNA and no fragment from HSV-2 DNA were observed, indicating that HSV1-TK-Dw is type specific for HSV-1 but T7-HSV2-TK is not specific for HSV-2. The DNA fragments were amplified from both HSV-1 and HSV-2 DNAs by primer sets T7-HSV1-TK and HSV2-TK-Dw (lanes 5 to 8) and T7-HSV2-TK and HSV2-TK-Dw (lanes 13 to 16), indicating that T7-HSV1-TK and HSV2-TK-Dw hybridize both types of HSV DNA. The hybridization site for HSV2-TK-Dw in the HSV-1 genome was identified by analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the PCR product and was in the region 5′-GTatcGAcAgaGTGCCAGCCCT (nucleotides 46,560 to 46,539 of the HSV-1 genome; capital letters show nucleotide identity with the primer) (20).

The primer set T7-VZV-TK and VZV-TK-Dw specifically amplified the VZV TK gene from VZV DNA samples (lanes 17 and 18) but not from HSV-1 DNA (lane 19). Therefore, the primer set for the VZV TK gene is specific for the VZV TK gene. The common primer set T7-HSV2-TK and HSV2-TK-Dw for HSV TK genes, described above, was unable to amplify the TK gene from VZV DNA (lane 20).

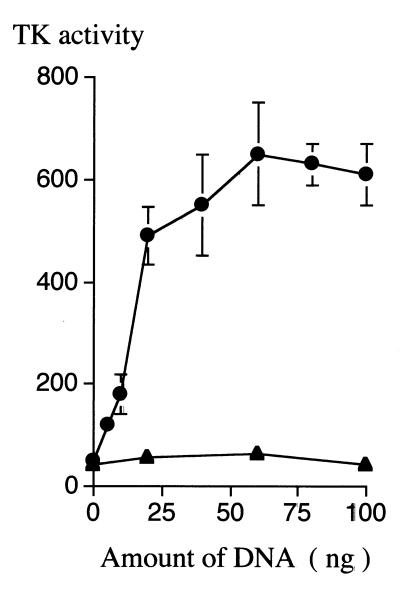

The conditions of in vitro transcription and translation for the PCR products of the TK genes was estimated on the basis of the TK activity (Fig. 2). Low TK activity rabbit reticulocytes was detected in a control reaction. Viral TK activity was expressed even with the addition of 5 ng of PCR products in the final 5 μl of the transcription mixture, and the highest activities were expressed with the addition of 60 to 80 ng of the PCR products. However, a statistically significant difference was not observed in TK activities expressed with the addition of 20 to 100 ng of DNA (P < 0.05 [χ2 test]), suggesting that the system does not require a strictly quantified amount of applied DNA. No viral TK activity was expressed with the addition of up to 100 ng of PCR products from the TK− strain, VRTK− (P < 0.001 [χ2 test]).

FIG. 2.

Correlation between amount of PCR products (nanograms of DNA) applied to an in vitro transcription-translation reaction and expressed TK activity (in picomoles per minute per microliter of mixture). The PCR conditions and purification of PCR products are described in detail in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the means ± standard errors [error bars] of triplicate experiments. Symbols: ●, HSV-1 VR-3 strain; ▴ VRTK− strain.

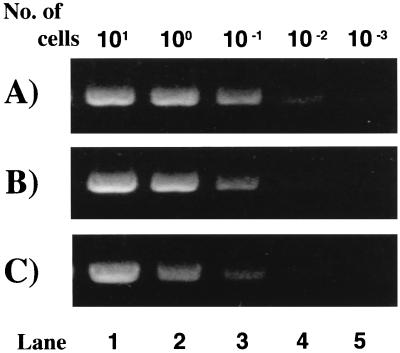

The sensitivities of PCR were estimated (Fig. 3). The signal of the amplified TK gene was detected in mixtures containing sample DNA corresponding to not less than 0.01 HSV-1-, 0.1 HSV-2-, and 0.1 VZV-infected cell. To accomplish in vitro transcription-translation of the TK gene, the minimum requirement of sample viral DNA was that contained in approximately 0.1 HSV-1-, HSV-2-, or VZV-infected cell.

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of PCR to HSV-1 TK (A), HSV-2 TK (B), and VZV TK (C) genes. The sample DNA, calculated to correspond to 10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 virus-infected cell, was added to 100 μl of PCR mixture, and PCR was carried out under the conditions described in Materials and Methods. After purification of PCR products with a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, 1 μl of the total 30-μl DNA suspension was analyzed on agarose gels. The amount of VZV TK gene in 1 μl of purified PCR products, amplified from 0.1 infected cell, was measured to be 40 ng by absorbance at 260 nm (panel C, lane 3).

Evaluation of the method.

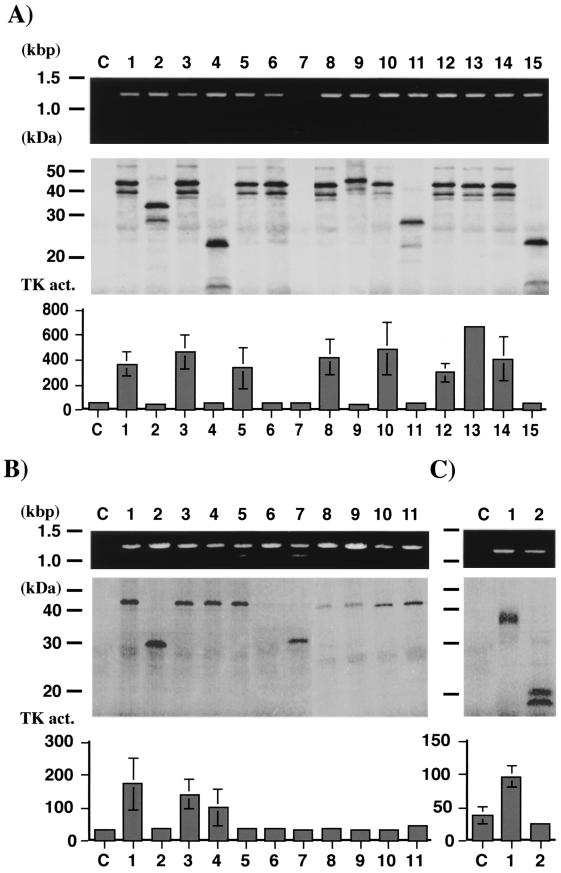

In order to evaluate the practicality of the method, 15 HSV-1, 11 HSV-2, and 2 VZV strains were analyzed. The strains used in these experiments are characterized in detail and summarized in Table 1. Wild-type HSV-1 TK genes expressed a major 43-kDa polypeptide and two minor polypeptides of 39 and 38 kDa, which may result from translational initiation at the second and third AUG codon as described previously (Fig. 4A) (11, 18, 19). Mutant TK genes coding for smaller or larger (TAR strain [Table 1]) polypeptides expressed polypeptides of the predicted size. A 6- to 14-fold enhanced TK activity compared with that in the control mixture was detected in the mixture expressing wild-type HSV-1 TK, but no increase was observed in the mixture expressing mutant TKs, even in the TKA mutant (the SC16 S1 strain) (Fig. 4A, lane 6). Similar results were observed in HSV-2 and VZV TK except for some differences as follows (Fig. 4B and C). (i) The VZV TK gene expressed two polypeptides (35 and 34 kDa) as described previously (18), but the HSV-2 TK gene expressed just one 43-kDa polypeptide. (ii) The TK activities expressed from the HSV-2 and VZV TK genes were lower than that from the HSV-1 TK gene. (iii) TK activity was not detected in the mixture expressing the TKA mutant (the 8708 and 4365-9 strains) (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 11), the same as HSV-1 TK.

FIG. 4.

Size of PCR products and size and activity (act.) of translated TK polypeptides in vitro. (A) HSV-1 TK. Lanes: C, control reaction without viral DNA; 1, VR-3; 2, VRTK−; 3, KOS; 4, KOSdlsactk; 5, SC16; 6, SC16 S1; 7, DM21; 8, TAS; 9, TAR; 10, BW-S; 11, BW-R; 12, KH52; 13, KH54; 14, WT51; 15, 11334. (B) HSV-2 TK. Lanes: C, control reaction without viral DNA; 1, UW268; 2, UWTK; 3, 186; 4, 8702; 5, 8708; 6, 8713; 7, 11575; 8, 11572; 9, 11571; 10, 11785; 11, 4365-9. (C) VZV TK. Lanes: C, control reaction without viral DNA; 1, YS; 2, YSR. The conditions of PCR and in vitro transcription-translation were described in Materials and Methods. TK activity is expressed as means ± standard errors (error bars) of triplicate experiments.

In conclusion, the method established in this study could identify HSV and VZV strains as wild type or mutant on the basis of the molecular mass and enzymatic activity of the TK polypeptide encoded by the strain, although the classification of ACVr mutant TKs as TK− or TKA was impossible.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have described a novel rapid screening method based on PCR technology for analyzing the TK gene phenotype. Using this method with PCR-directed sequencing, the genotype and phenotype of TK from HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV strains could be identified in 2 days, and this speed would allow the timely and appropriate selection of antiviral chemotherapy.

Another important merit of the method is that the phenotype of viral TK can be identified without virus isolation. In the case of HSV encephalitis, HSV was isolated from only 4% of cerebrospinal fluid samples, but DNA was detected by PCR in about 98% of cerebrospinal fluid samples from individuals positive for HSV by brain biopsy (22). This result led to the reluctance of clinicians to perform a highly invasive diagnostic procedure, brain biopsy, and the laboratory diagnosis of HSV encephalitis was greatly facilitated by PCR without virus isolation (1, 42). Even in these cases, PCR-based in vitro translation of the TK gene can clarify the TK phenotype and provide information with which to determine the best course of antiviral chemotherapy. Moreover, by virtue of this method, it is expected that the study of the virulence of ACVr mutants could be enhanced. Because all reported ACVr strains were isolated from skin or mucosal regions, including corneas and a larynx, it is not clear that these strains can replicate in other tissues or if they are neurovirulent in humans. Phenotypic analysis of the TK gene, which can be amplified from various tissues under various conditions, including fixed samples, could produce novel information.

In some clinical cases, ACVr strains were isolated as mixed populations with the wild-type strain (4, 28, 38). Our method could identify different TK polypeptide sizes from a sample containing a mixture of a wild-type (VR-3) strain and a premature truncated TK mutant (the VRTK− strain) in various ratios. However, no significant results suggesting the coexistence of the TK mutant in wild-type populations were observed by enzymatic assay (data not shown). This is one limitation of the method, and in this case virus isolation and plaque purification are required before analysis of the virus strain is carried out.

At present, a plaque reduction assay or a dye uptake assay in Vero cells is the most popular and standard assay with a cut-off value between ACV-sensitive and -resistant viruses (5, 21), although these may be replaced by the modified plaque reduction assay developed by Tebas et al. (40). Plaque autoradiography using TK-negative cell lines is the most sensitive assay for analysis of viral TK activity and identification of each virion in mixed populations (13, 41). We have established and reported a novel assay in this paper that makes up for the shortcomings of current standard methods, in terms of length of time required and difficulties in virus isolation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Donald M. Coen, Jack Hill, Haruhiko Machida, and Yukihiro Nishiyama for providing the HSV strains.

This work was supported by a grant from the Charitable Trust Clinical Pathology Research Foundation of Japan in 1999.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aurelius E, Johansson B, Skoldenberg B, Staland A, Forsgren M. Rapid diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by nested polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. Lancet. 1991;337:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiba A, Suzutani T, Saijo M, Koyano S, Azuma M. Analysis of nucleotide sequence variations in herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, and varicella-zoster virus. Acta Virol. 1998;42:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coen D M, Kosz-Vnenchak M, Jacobson J G, Leib D A, Bogard C L, Schaffer P A, Tyler K L, Knipe D M. Thymidine kinase-negative herpes simplex virus mutants establish latency in mouse trigeminal ganglia but do not reactivate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4736–4740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins P, Larder B A, Oliver N M, Kemp S, Smith I W, Darby G. Characterization of a DNA polymerase mutant of herpes simplex virus from a severely immunocompromised patient receiving acyclovir. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:375–382. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-2-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins P, Ellis M N. Sensitivity monitoring of clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus to acyclovir. J Med Virol Suppl. 1993;1:58–66. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darby G, Field H J, Salisbury S A. Altered substrate specificity of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase confers acyclovir-resistance. Nature. 1981;289:81–83. doi: 10.1038/289081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efstathiou S, Kemp S, Darby G, Minson A C. The role of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase in pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:869–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-4-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis M N, Keller P M, Fyfe J A, Martin J L, Rooney J F, Straus S E, Lehrman S N, Barry D W. Clinical isolate of herpes simplex virus type 2 that induces a thymidine kinase with altered substrate specificity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1117–1125. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Englund J A, Zimmerman M E, Swierkosz E M, Goodman J L, Scholl D R, Balfour H H., Jr Herpes simplex virus resistant to acyclovir. A study in a tertiary care center. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:416–422. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-3-112-6-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field H J, Darby G. Pathogenicity in mice of strains of herpes simplex virus which are resistant to acyclovir in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:209–216. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haarr L, Marsden H S, Preston C M, Smiley J R, Summers W C, Summers W P. Utilization of internal AUG codons for initiation of protein synthesis directed by mRNAs from normal and mutant genes encoding herpes simplex virus-specified thymidine kinase. J Virol. 1985;56:512–519. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.2.512-519.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill E L, Hunter G A, Ellis M N. In vitro and in vivo characterization of herpes simplex virus clinical isolates recovered from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2322–2328. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horsburgh B C, Chen S-H, Hu A, Mulamba G B, Burns W H, Coen D M. Recurrent acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex in an immunocompromised patient: can strain differences compensate for loss of thymidine kinase in pathogenesis? J Infect Dis. 1998;178:618–625. doi: 10.1086/515375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kost R G, Hill E L, Tigges M, Straus S E. Recurrent acyclovir-resistant genital herpes in an immunocompetent patient. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1777–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacey S F, Suzutani T, Powell K L, Purifoy D J M, Honess R W. Analysis of mutations in the thymidine kinase genes of drug-resistant varicella-zoster virus populations using the polymerase chain reaction. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:623–630. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machida H. Comparison of susceptibilities of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:524–526. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machida H, Nishitani M, Suzutani T, Hayashi K. Different antiviral potencies of BV-araU and related nucleoside analogues against herpes simplex virus type 1 in human cell lines and Vero cells. Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35:963–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1991.tb01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahalingam R, Cabirac G, Wellish M, Gilden D, Vafai A. In-vitro synthesis of functional varicella zoster and herpes simplex viral thymidine kinase. Virus Genes. 1990;4:105–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00678403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsden H S, Haarr L H, Preston C M. Processing of herpes simplex virus proteins and evidence that translation of thymidine kinase mRNA is initiated at three separate AUG codons. J Virol. 1983;46:434–445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.2.434-445.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGeoch D J, Dalrymple M A, Davison A J, Dolan A, Frame M C, McNab D, Perry L J, Scott J E, Taylor P. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1991;69:1531–1574. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaren C, Ellis N M, Hunter G A. A colorimetric assay for the measurement of the sensitivity of herpes simplex viruses to antiviral agents. Antivir Res. 1983;3:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(83)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahmias, A. J., R. J. Whitley, A. N. Visintine, Y. Takei, C. A. Alford, Jr., and The Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. 1982. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis: laboratory evaluations and their diagnostic significance. J. Infect. Dis. 145:829–836. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Nugier F, Colin J N, Aymard M, Langlois M. Occurrence and characterization of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus isolates: report on a two-year sensitivity screening survey. J Med Virol. 1992;36:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890360102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyquist A-C, Rotbart H A, Cotton M, Robinson C, Weinberg A, Hayward A R, Berens R L, Levin M J. Acyclovir-resistant neonatal herpes simplex virus infection of the larynx. J Pediatr. 1994;124:967–971. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker A C, Craig J I O, Collins P, Oliver N, Smith I. Acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus infection due to altered DNA polymerase. Lancet. 1987;ii:1461. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parris D S, Harrington J E. Herpes simplex virus variants resistant to high concentrations of acyclovir exist in clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22:71–77. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pottage J C, Kessler H A. Herpes simplex virus resistance to acyclovir: clinical relevance. Infect Agents Dis. 1995;4:115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacks S L, Wanklin R J, Reece D E, Hicks B A, Tyler K L, Coen D M. Progressive esophagitis from acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex. Clinical roles for DNA polymerase mutants and viral heterogeneity? Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:893–899. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safrin, S., C. Crumpacker, P. Chatis, R. Davis, R. Hafner, J. Rush, H. A. Kessler, B. Landry, J. Mills, and other members of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. 1991. A controlled trial comparing foscarnet with vidarabine for acyclovir-resistant mucocutaneous herpes simplex in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 325:551–555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Saijo M, Suzutani T, Murono K, Hirano Y, Itoh K. Recurrent acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex in a child with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:311–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saijo M, Suzutani T, Itoh K, Hirano Y, Murono K, Nagamine M, Mizuta K, Niikura M, Morikawa S. Nucleotide sequence of thymidine kinase gene of sequential acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus type 1 isolates recovered from a child with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: evidence for reactivation of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. J Med Virol. 1999;58:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakuma S, Yamamoto M, Kumano Y, Mori R. An acyclovir-resistant strain of herpes simplex virus type 2 which is highly virulent for mice. Arch Virol. 1988;101:169–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01310998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakuma T. Strains of varicella-zoster virus resistant to 1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-E-5-(2-bromovinyl)uracil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:742–746. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibrack C D, Gutman L T, Wilfert C M, McLaren C, St. Clair M H, Keller P M, Barry D W. Pathogenicity of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus type 1 from an immunodeficient child. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:673–682. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzutani T, Machida H, Sakuma T. Efficacies of antiherpesvirus nucleosides against two strains of herpes simplex virus type 1 in Vero and human embryo lung fibroblast cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1046–1052. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.7.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzutani T, Machida H, Sakuma S, Azuma M. Effects of various nucleosides on antiviral activity and metabolism of 1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-E-5-(2-bromovinyl)uracil against herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1547–1551. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.10.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzutani T, Koyano S, Takada M, Yoshida I, Azuma M. Analysis of the relationship between cellular thymidine kinase activity and virulence of thymidine kinase-negative herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:787–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swetter S M, Hill E L, Kern E R, Koelle D M, Posavad C M, Lawrence W, Safrin S. Chronic vulvar ulceration in an immunocompetent woman due to acyclovir-resistant, thymidine kinase-deficient herpes simplex virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:543–550. doi: 10.1086/514229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka S, Toh Y, Mori R. Molecular analysis of a neurovirulent herpes simplex virus type 2 strain with reduced thymidine kinase activity. Arch Virol. 1993;131:61–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01379080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tebas P, Scholl D, Jollick J, McHarg K, Arens M, Olivo P D. A rapid assay to screen for drug-resistant herpes simplex virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:217–220. doi: 10.1086/517357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tenser R B, Jones J C, Ressel S J, Fralish A. Thymidine plaque autoradiography of thymidine kinase-positive and thymidine kinase-negative herpesviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:122–127. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.1.122-127.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitley R J, Lakeman F. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:414–420. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]