Abstract

Background

In most developing countries, meeting young people’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs remains a problem. Despite policy initiatives and strategic measures aimed at increasing youth utilization of sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia, its utilization remains very low. Therefore, this study aimed to assess Ethiopia’s youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services’ utilisation and determinants.

Methods

Scopus, Medline, Google Scholar, and CINAHL databases were searched for articles published until March 2021. The pooled prevalence and effect size of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service use and associated factors were estimated using a weighted DerSimonian-laird random effect model. The I2 statistics were used to determine the degree of heterogeneity. The funnel plot and Egger's regression test were used to examine publication bias. Subgroup analyses were performed to reduce underlying heterogeneity.

Results

One thousand one hundred and ninety-one articles were generated from various databases, and a final 26 articles were included in the review, including 16246 participants. Ethiopia’s pooled prevalence of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization was 42.73 % (95% CI: 35.38–50.09). The findings of this study showed that grade level 11–12, grade level 9–10, close to home sexual and reproductive health services, male sex, and discussion of sexual and reproductive health service with family, friends, and groups, ever experience sexual activity were associated with utilization of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. Maternal educational status secondary school and above, age 15–19 years, age 20–24 years, having ever experienced reproductive problems, living with a partner, living alone, knowing about sexual and reproductive health, having a convenient working hour for youth-friendly service, and participation in a school clubs were also associated with the utilization of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services.

Conclusion

We found several determinant factors for adolescent and youth utilization of sexual and reproductive health services. The review highlights the importance of improving service usage through youth education and promotion and the scaling up and institutionalizing of youth-friendly services through extensive capacity building.

Keywords: Youth, Youth-friendly, Sexual and reproductive health, Utilization, Ethiopia

Youth; Youth-friendly; Sexual and reproductive health; Utilization; Ethiopia.

Plain English summary

Ethiopia’s total population is around 45 % under the age of 30. The largest group of Ethiopians to enter adulthood in history is young people aged 10–24. Several factors can be attributed to Ethiopia’s increased emphasis on the well-being of teenagers and youth.

There are inconsistencies in the prevalence and determinants of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization in Ethiopia. As a result, the purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled prevalence of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization and the factors influencing it.

Studies on the use of sexual and reproductive health services and associated factors among Ethiopian young people aged 10 to 24 years were included in this systematic review. The review included published and unpublished papers in Ethiopia from 2010 to 30 March, 2021. The study included 26 trials with a total of 16246 participants.

Overall, 18.4% to 79.5 % of young people use youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. The overall pooled prevalence of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization was 42.73 % (95 % CI, 35.38 % - 50.09%). The findings of this review revealed that the use of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services was associated with grade level 11–12, grade level 9–10, close to home sexual and reproductive health service, male sex, discussion of sexual and reproductive health services with family, friends, and groups, and ever experience sexual activity, maternal educational level secondary school and above, and ever experience sexual activity.

1. Introduction

Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not just the absence of disease or infirmity, in all aspects of the reproductive system and its functions and processes [1]. Young people are classified as those aged 10–24 years, including adolescents (10–19 years) and youths (15–24 years), and they form a crucial stage of transition between childhood and adulthood [2].

Nearly two billion young people in the world today have specific health and development needs, and many face threats to their well-being, such as poverty, a lack of access to health information and services, and unsafe environments [3]. They face several significant sexual and reproductive health challenges, such as limited access to youth-friendly services that provide information on growth, sexuality, and family planning. This has led to youth engaging in risky sexual behaviours, which has resulted in high STI and HIV prevalence, early pregnancy, and vulnerability to delivery complications, all of which have resulted in high rates of death and disability [4].

Consequently, many of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) rely on adolescent sexual and reproductive health rights (ASRHR), and these recommended indicators correspond to three of them: health (Goal 3), education (Goal 4) and gender equality (Goal 5) [5]. The four significant goals of adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) are to create an enabling and supportive environment for young people, improve their knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviours, increase young people’s use of services, and increase their participation in programs [3,6].

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs of young people/youth are frequently underestimated in many African countries, despite their demonstrated need and the urgency of these services [7]. There are significant gaps among youth in terms of receiving information, the effectiveness of the youth-friendly services (YFS), and skills influenced by culture, and governmental and financial policies [8]. Adolescents and youths frequently lack basic reproductive and sexual health information, knowledge, and experience, and they are less comfortable accessing reproductive and sexual health services than adults. Nearly one-third (30%) of Ethiopian healthcare workers had negative attitudes toward providing RH services to unmarried adolescents [9].

The youth-friendly service program has the potential to improve health services for young people and their health outcomes. Youth-friendly services are affordable, acceptable, and relevant. They are in the right spot, at the right price (free if necessary), and presented in the right way for young people to agree. They are efficient, clean, and cost-effective. They cater to the specific needs of young people who return when they need to and refer their friends to them [10]. Ethiopia has a predominantly young population. Around 45% of Ethiopia's total population is under the age of 30. Young people aged 10–24 are the largest Ethiopians to enter adulthood in history [11]. Even though Ethiopia has a cadre of health extension workers (HEWs) who provide primary preventive health care at the community level and a national adolescent and youth reproductive health strategy access and experience with these health services is limited [12].

Gender inequality, sexual coercion, early marriage, high levels of teenage pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV and AIDS, are among many young Ethiopians’ sexual and reproductive health problems. These are further complicated by limited access to reproductive health information and good quality adolescent and youth-friendly reproductive health services [13]. According to the Ethiopian demography and health survey (EDHS) 2016, the national prevalence of early marriage before the age of 18 years was 58% [14]. In Eastern Ethiopia, the prevalence of unmet contraception need was 34.6% among young women aged 14–24 years [15]. According to a multilevel analysis of a study in Ethiopia, out of 2679 participants, 2134 (79.6%) of women aged 20–24 years had a pregnancy during their adolescent years [16]. In Wogedi district, South Wollo zone, Amhara Region and Kersa district, East Hararghe Zone, Oromia Regional State, respectively, the frequency of early pregnancy was 28.6% and 30.2 % [17, 18]. In Ethiopia, 690,000 people were infected with HIV in 2018, while 23, 000 people were newly infected and 11,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses. In Ethiopia, women are disproportionately affected by HIV: 410, 000 (63.08 %) of the 650, 000 HIV-positive adults were women [19]. Adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 are up to three times more likely to be HIV positive as compared to their male counterparts [20].

Ethiopia's increased emphasis on the well-being of adolescents and youth can be attributed to various factors. This demographic makes up a significant portion of the population of the country (33.8 %). Almost one-third of all women between the ages of 15 and 24 live in rural areas [21]. .Healthy adolescents are a valuable asset and resource who can make meaningful contributions to their families, neighbourhoods, and country, both now and in the future, as agents of social change rather than merely beneficiaries of social programs [22]. Ethiopia has focused on improving sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for young people, including the establishing of youth-friendly services (YFS). There are still high rates of child marriage, unmet family planning needs, and early childbearing, particularly in rural areas, where more than 84 % of the population lives [23].

In Ethiopia, there are inconsistencies in the prevalence and determinants of youth-friendly SRH service utilization. As a result, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization and the factors that influence it.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis incorporates relevant articles on the use and determinants of youth-friendly SRH services in Ethiopia. It is PROSPERO-registered (#CR D42021257349). PRISMA guidelines were followed in conducting the review and reporting the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis [24].

2.1. Selection and eligibility criteria

2.1.1. Eligibility criteria

This systematic review included studies on SRH service utilization and associated factors among Ethiopian young people aged 10–24 years. Studies that reported the prevalence and factors influencing the use of SRH services were included. The review included both published and unpublished studies conducted in Ethiopia between 2010 and 30 March, 2021, with all full-text articles written in English.

2.1.2. Exclusion criteria

Editorials, newspaper articles, and other forms of popular media were excluded, as were studies that did not report either prevalence or risk factors for SRH service utilization among adolescents and youth groups.

2.2. Data sources and search strategy

Articles for this systematic review were found through electronic web-based searches on Medline/PubMed, Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and CINAHL. Searches were conducted for Ethiopian-published studies and Grey literature deposited on the websites of universities and research institutes. Our search strategy included key terms and phrases such as “adolescent,” “youth,” “teenagers,” “young,” “sexual and reproductive health service,” “youth-friendly,” “utilization,” “determinant,” “risk,” and “associated factors,” as well as “Ethiopia.” The following search strategy was used to suit the advanced PubMed database: (("sexual behavior" [MeSH Terms] OR ("sexual" [All Fields] AND "behavior" [All Fields]) OR "sexual behavior" [All Fields] OR "sexual" [All Fields]) AND ("reproductive health services" [MeSH Terms] OR ("reproductive" [All Fields] AND "health" [All Fields] AND "services" [All Fields]) OR "reproductive health services" [All Fields]) AND ("statistics and numerical data" [Subheading] OR ("statistics" [All Fields] AND "numerical" [All Fields] AND "data" [All Fields]) OR "statistics and numerical data" [All Fields] OR "utilization" [All Fields]) AND ("ethiopia" [MeSH Terms] OR "ethiopia" [All Fields])) AND (("systematic review" [All Fields] OR "systematic reviews as topic" [MeSH Terms] OR "systematic review" [All Fields]) AND ("meta-analysis" [All Fields] OR "meta-analysis as topic" [MeSH Terms] OR "meta-analysis" [All Fields])). Then we found 583 articles using PubMed, 577 articles using Google Scholar, 21 articles using CINAHL, and 10 articles using other databases. There were a total of 1191 articles retrieved (Additional file 1).

2.3. Operational definitions

Sexual and reproductive health services utilization assessed based on utilization of at least one of SRH services provided to adolescents and youths, which includes counseling, information, and health education, family planning services, HIV counseling and testing, pregnancy test, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted illnesses, abortion and post-abortion care, antenatal, delivery, and postnatal care services [25].

2.4. Study selection

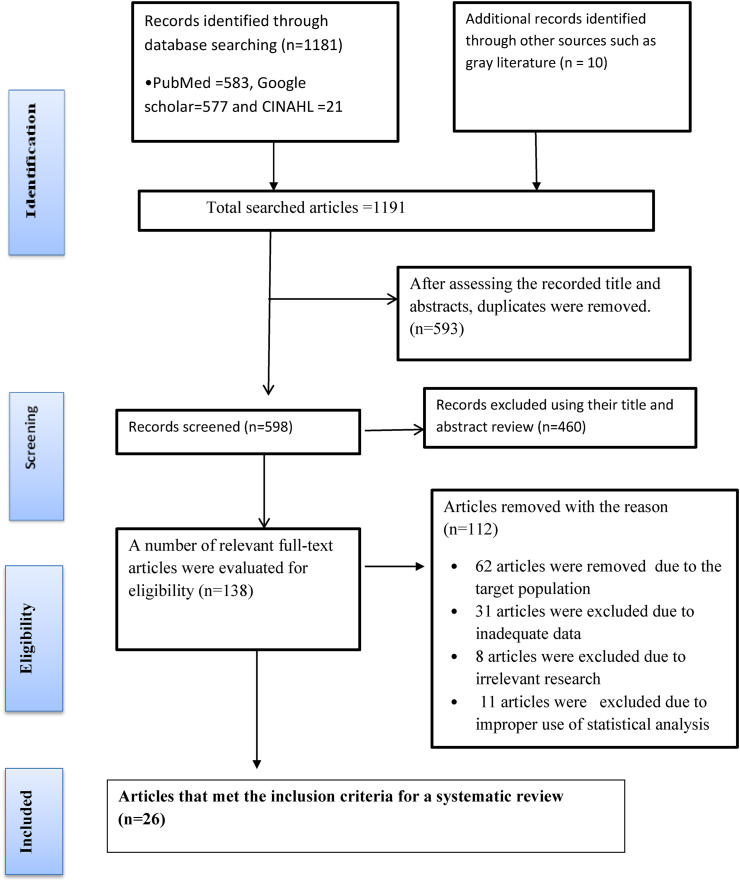

A total of 1191 primary studies were identified using data-driven searching. All retrieved studies were exported to Endnote version 7 reference manager software to eliminate duplicate studies [26]. Due to duplication, 593 of the studies were excluded. Four hundred sixty articles were excluded after reviewing the titles and abstracts of 598 articles. One hundred thirty-eight full-text articles were evaluated for eligibility; of those analyzed, 62 articles were omitted due to the target population, 31 excluded due to inadequate data, eight excluded due to irrelevant research, and 11 excluded due to improper use of statistical analysis. Finally, for the study and meta-analysis, 26 studies were included (Figure 1). The abstract and full-text reviews were carried out by four independent authors (HG, MD, BG, and AD).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for selection of studies publication.

2.5. Data extraction and quality assessment

Each study's scientific quality and strength were assessed using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale quality assessment tool adapted for cross-sectional study quality assessments. (Additional file 2) [27]. The reference management software (Endnote version X7) was initially used to combine database search results and remove duplicate articles manually. The titles and abstracts of the studies were then thoroughly evaluated based on the outcome's relevance. The full text of the remaining articles was reviewed for eligibility using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those primary studies with a score of 8 considered high quality, score = 6–7 moderate quality and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Four reviewers (HG, MD, BG, and AD) extracted data from the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using a standardized data extraction checklist. Uncertainties during the extraction process were resolved through logical consensus among the four authors, and the final consensus was approved with the participation of authors (GA and WN).

2.6. Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 26 articles were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. All articles were cross-sectional studies. 13 studies were institutionally based, and 13 were community-based studies. All articles were assessed from all regions of Ethiopia, and most of the studies were eligible and included from the Amhara region. Included studies were published from 2010-2021. A total of 16246 sample size were included in this review, and the study populations were adolescent (age 10–19 years), youth (age 15–24 years), and young (age 10–24 years) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included articles for systematic review for youth-friendly SRH service utilization in Ethiopia.

| First Author and Year | Region | Study design | Target gender | Study area | Study Population | Sample Size | Response Rate | RHS utilization | Outcome measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abate et al., 2019 | Amhara | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 376 | 94 | 24.6 | RHS utilisation and its associated factors |

| Simegn A et al., 2020 | Amhara | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 696 | 99.1 | 28.8 | Youth-friendly SRH service utilisation |

| Feleke et al., 2013 | Amhara | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 15–19 year | 1300 | 99.23 | 79.5 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Abebe et al., 2014 | Amhara | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 818 | 100 | 32.2 | The utilisation of youth-friendly RHS and associated factors |

| Ayehu et al., 2016 | Amhara | Community -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban and rural | Young 10–24 year | 781 | 95.5 | 41.2 | Young people SRHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Tlaye et al., 2018 | Amhara | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 15–19 year | 682 | 95.01 | 33.8 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Abajobir AA et al., 2014 | Amhara | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 10–19 year | 415 | 92 | 21.5 | RH knowledge and service utilisation |

| Negash W et al., 2016 | Amhara | A community based cross-sectional study using quantitative and qualitative method | Both | Urban and rural | Young 14–24 year | 391 | 100 | 54.7 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Yasine T, 2020 | Amhara | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Rural | Young 15–24 year | 572 | 100 | 34.31 | Youth-friendly service utilisation and associated factors |

| Gurara AM et al, 2020 | Oromia | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 15–19 year | 367 | 97.8 | 34 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Wachamo D et al., 2020 | Oromia | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 519 | 93.7 | 58.6 | SRHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Fikadu A et al., 2020 | Oromia | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 376 | 100 | 20.7 | Youth-friendly RH service utilisation and associated factors |

| Motuma A et al., 2016 | Harar | A community based cross-sectional study using quantitative and qualitative method | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 845 | 100 | 63.8 | The utilisation of youth-friendly service and associated factors |

| Binu W et al., 2018 | Oromia | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 768 | 96 | 21.2 | SRHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Helam D et al., 2017 | SNNP | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban & rural | Youth 15–24 year | 702 | 90.3 | 38.5 | Utilisation and factors affecting adolescent and youth-friendly RHS |

| Ansha MG et al., 2017 | Oromia | A community based cross-sectional study using quantitative and qualitative method | Both | Rural | Adolescent 10–19 year | 402 | 100 | 45.8 | RHS Utilization and associated factors |

| Gebreselassie B et al., 2015 | Oromia | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 15–19 year | 403 | 98.5 | 71.9 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Kerbo AA et al., 2018 | Oromia | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 390 | 97.9 | 46.9 | Youth-friendly SRH service utilisation and associated factors |

| Bilal SM et al., 2015 | Tigray | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Adolescent 15–19 year | 1042 | 99 | 22 | Utilization of SRHS |

| Kahsay K et al., 2016 | Tigray | A community based cross-sectional study using quantitative and qualitative method | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 330 | 100 | 69.1 | The utilisation of Youth friendly service and associated factors |

| Temesgen T, 2017 | SNNP | quantitative cross sectional study supplemented by qualitative method | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 385 | 99 | 59 | Utilization of RHS |

| Dagnew T et al., 2015 | Amhara | Community-based cross-sectional | Both | Urban & rural | Adolescent 15–19 year | 690 | 100 | 45 | Health service utilization and satisfaction |

| Gelagay AA et al., 2018 | Amhara | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Rural | Youth 15–24 year | 574 | 98.4 | 18.4 | SRHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Lejibo TT et al., 2017 | SNNP | Community-based cross-sectional | Females only | Rural | Adolescent 15–19 year | 844 | 96.2 | 47.2 | SRHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Tefera T, 2015 | Addis Ababa | Institutional -based cross-sectional | Both | Urban | Youth 15–24 year | 734 | 94.5 | 28.7 | RHS utilisation and associated factors |

| Gebreyesus H et al., 2019 | Tigray | Community-based cross-sectional | Females only | Rural | Adolescent 15–19 year | 844 | 99.6 | 69.7 | Determinants of RHS utilisation |

2.7. Definition of the outcome of interest

The primary outcome of this systematic review and meta-analysis was the prevalence of sexual and reproductive health service utilization among adolescents aged 10-15 years and youths aged 15-24 years. The review's second goal was to identify the determinants of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization in Ethiopia.

2.8. Data synthesis and analysis

STATA-11 software was used for data entry and statistical analysis. Tables and figures were used to summarize the selected studies and results descriptively. A meta-analysis was performed on studies that provided a comparable classification of the determinants and outcome variables. We used estimates of adjusted odds ratios with confidence intervals (CI) to measure association in the meta-analysis. A random-effect model was used to estimate the pooled estimate of utilization and determinant factors of youth-friendly SRH service utilization, measured by prevalence rates and odds ratio with 95% CI.

2.9. Publication bias and heterogeneity

A random-effects model was used when there was moderate-to-high heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was used when there was no heterogeneity among included studies. We used the I2 statistic to measure study heterogeneity, which defines the percentage of total variation between studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Forest plot, Cochrane's Q statistic (P-value < 0.1), and inverse variance index (I square tests) (>50%) were used to assess statistical heterogeneity. The I2statistic values of zero, 25, 50, and 75%, respectively, denote true homogeneity, low heterogeneity, moderate heterogeneity, and high heterogeneity [28]. A weighted DerSimonian -Laird random-effects model was used for pooled analysis [29].

Egger and Begg's statistical test was used to check the statistical significance of publication bias which showed the presence of publication bias (Egger test, p < 0.05) [30]. The Duval and Tweedie nonparametric trim and fill analysis was performed [31].

3. Results

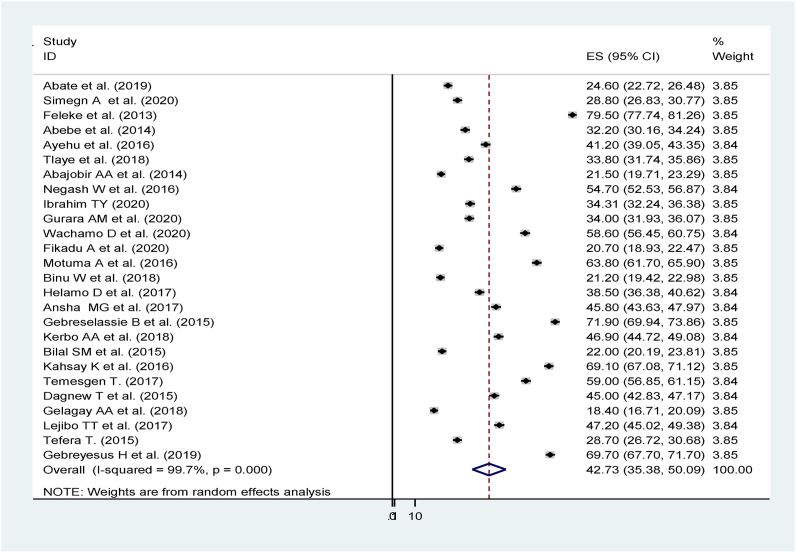

A total of twenty-six studies with 16246 participants were included in the analysis. The use of youth-friendly SRH services varies by region, as well as by study time and location. This frequency varies between 18.4% among preparatory school students in Mecha district, northwest Ethiopia, and 79.5 % among adolescents in Gondar town, Ethiopia [32, 33]. The overall pooled prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization was 42.73 % (95 % CI, 35.38 % - 50.09%), and the heterogeneity test revealed high variability, I2 = 99.7 %, indicating that the random effect model was used in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change as a result of the sensitivity analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the pooled prevalence of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization in Ethiopia.

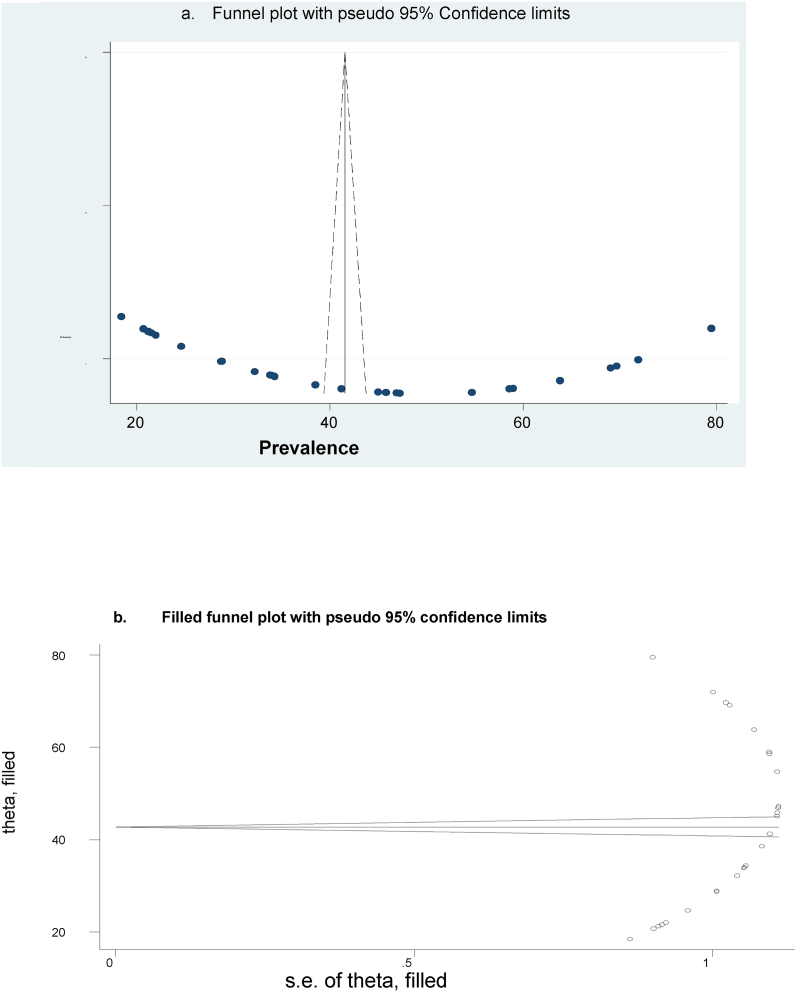

3.1. Publication bias

A funnel plot (subjectively) and the Eggers regression test (objectively) assessed publication bias. A funnel plot revealed symmetrical distribution for this review (Figure 3a). The p-value for Egger's regression test was 0.043, indicating the presence of publication bias (Table2). However, Duval and Tweedie's nonparametric trim and fill analysis did not account for additional studies (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

a) funnel plot was used to examine the publication bias of 26 studies. b) No additional studies were added to the trim and fill analysis to correct for publication bias.

Table 2.

Egger's test.

| Std_Eff | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P > t | [95% Conf. | Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | -51.57797 | 43.83863 | -1.18 | 0.251 | -142.0565 | 38.90052 |

| bias | 92.07797 | 43.19765 | 2.13 | 0.043 | 2.922412 | 181.2335 |

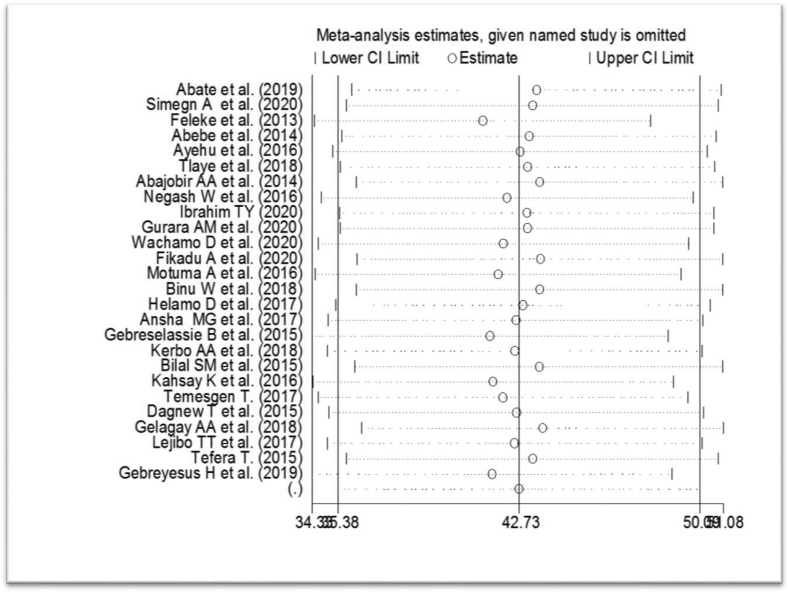

4. Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a random-effects model to find outliers of a single study's impact on the overall meta-analysis outcome. The result revealed no clear evidence for the effect of a single study on the overall meta-analysis result (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analyses for the prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization in Ethiopia.

4.1. Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was done based on the study setting, region, and year of publication. This subgroup analysis revealed that the highest prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization was found in community-based studies, 52.26% [95% CI: 42.11–62.42], and the lowest prevalence was found in institutional base studies 33.20% [95%CI: 26.20–40.37]. The pooled effect of three studies in the Tigray region showed more prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization 53.60 % [95%CI:21.59–85.60] and the lowest prevalence found in 11 studies Amhara region 37.64% [ 95% CI:26.46–48.81]. The pooled prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization from 2010-2015 and 2016–2020 was similar findings 42.97 % [95%CI: 24.75–61.37] and 42.64% [95%CI: 34.93–50.36] respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the youth-friendly SRH service utilisation in Ethiopia.

| Variables | Characteristics | Number of included studies | Prevalence (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study setting | Institutional based | 13 | 33.20 (26.20–40.37) |

| Community-based | 13 | 52.26 (42.11–62.42) | |

| Region | Amhara | 11 | 37.64 (26.46–48.81) |

| Oromo | 7 | 42.72 (28.02–57.43) | |

| SNNP | 3 | 48.23 (36.52–59.95) | |

| Tigray | 3 | 53.60 (21.59–85.60) | |

| Publication year | 2010–2015 | 7 | 42.97 (24.75–61.37) |

| 2016–2020 | 19 | 42.64 (34.93–50.36) |

5. Determinant factors with youth-friendly SRH service utilization

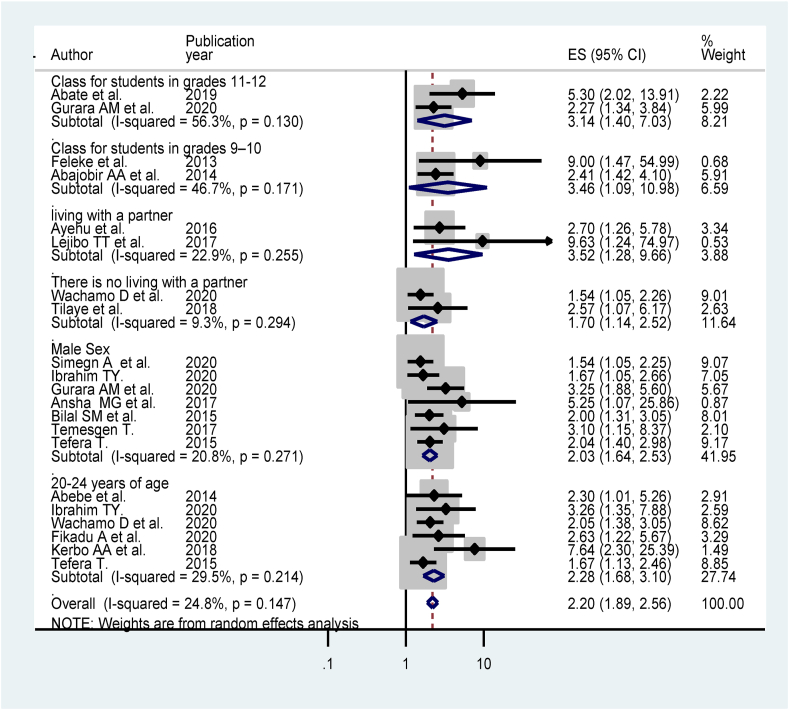

The pooled effect of two studies [34, 35] showed that students who were grade level 11–12 were 3.14 times (AOR = 3.14; 95% CI:1.40–7.03) more likely to utilize SRH services in Ethiopia as compared to students whose grade level 9–10. The pooled effect of two studies [33, 36] showed that students who were grade level 9–10 were 3.46 times more likely to utilize sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia as compared to elementary school students (grade 1-8) (AOR = 3.46; 95% CI:1.09–10.98). The pooled effect of two studies [37, 38] found that living with a partner was significantly associated with the use of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services (AOR = 3.52; 95 % CI:1.28–9.66) as compared to those living alone. The pooled effect of two studies [39, 40] revealed that no living with a partner is 1.7 times more likely to utilize youth-friendly SRH services than those living with family (AOR = 1.70; 95% CI:1.14–2.52). The pooled effect of seven studies [25, 35, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45] showed that the male gender increased two times the odds of youth-friendly SRH services utilization compared to females (AOR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.64–2.53). The pooled effect of six studies [40, 41, 45, 46, 47, 48] showed the association of age groups 20–24 years were increased 2.28 times the odds of youth-friendly SRH services utilization compared to younger age (15–19 years) (AOR = 2.28; 95% CI:1.68–3.10) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the pooled association between a socio-demographic variable and youth-friendly SRH service utilization in Ethiopia.

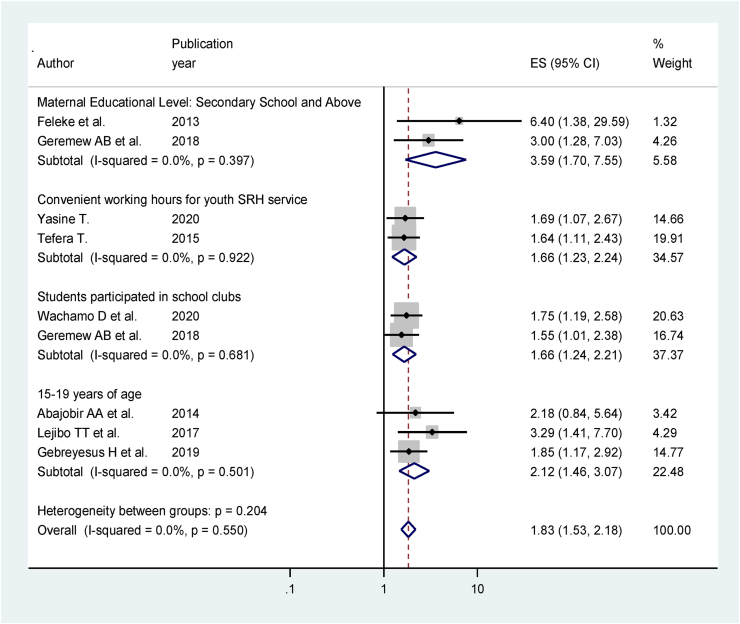

The pooled effect of three studies [36, 38, 49] showed the association of age groups 15–19 years were increased 2.12 times the odds of youth-friendly SRH services compared to younger age 10–15 years (AOR = 2.12; 95% CI:1.46–3.07). The pooled effect of two studies [33, 49] revealed that maternal educational level secondary school and above was increased 3.59 times the odds of youth-friendly SRH services utilization compared to maternal educational level unable to read and write (AOR = 3.59; 95% CI:1.70–5.77). The pooled effect of two studies [32, 40] revealed that students who participated in school clubs were 1.66 times more likely to utilize youth-friendly SRH health services (AOR = 1.66; 95% CI:1.24–2.21). The pooled effect of two studies [41, 45] showed that the convenient working time of SRH service increased 1.66 times the odds of utilizing youth-friendly SRH services (AOR = 1.66; 95 % CI:1.23–2.24). The heterogeneity test indicated I2 = 0.0 %, and hence fixed model was assumed in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change significantly as a result of the sensitivity analysis (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the pooled association between a socio-demographic variable and youth-friendly SRH service utilization in Ethiopia.

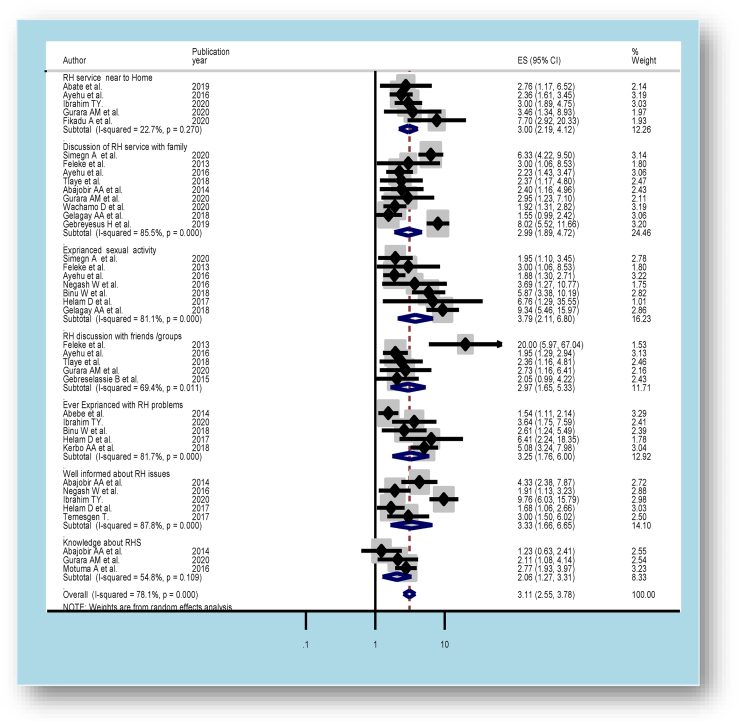

The pooled effect of five studies [33, 35, 37, 39, 50] found that discussing SRH issues with friends or groups increased almost four times the odds of youth-friendly SRH services utilization (AOR = 2.97; 95% CI:1.65–5.33). Heterogeneity test indicated I2 = 69.4 %, and hence random effect model was assumed in the analysis. Sensitivity analysis did not bring significant change in the overall ORs (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot for the pooled association between RH related variables and youth-friendly SRH service utilization in Ethiopia.

The pooled effect of nine studies in Ethiopia found that [25, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 39, 44, 49] discussing SRH issues with family was increased almost three times the odds of the utilization of youth-friendly SRH services (AOR = 2.99; 95% CI:1.89–4.72) The heterogeneity test revealed high variability, I2 = 85.5%, indicating high heterogeneity, so the random effect model was assumed in the analysis. Sensitivity analysis revealed that there was no change in the overall ORs (Figure 7).

The pooled effect of five studies [36, 41, 44, 51, 52] found that being well-informed about RH issues was associated with using youth-friendly SRH services (AOR = 3.33; 95% CI:1.66–6.65). Because the high heterogeneity test revealed I2 = 87.8 %, a random model was assumed in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change significantly as a result of the sensitivity analysis (Figure 7).

The pooled effect of three studies [35, 36, 53] found that knowledge about SRH was two times more likely to utilize youth-friendly SRH services (AOR = 2.06; 95 % CI:1.27–3.31). Because the moderate heterogeneity test revealed I2 = 54.8 %, a random model was assumed in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change significantly as a result of sensitivity analysis (Figure 7).

The pooled effect of seven studies found that [25, 32, 33, 37, 51, 52, 54] having ever engaged in sexual activity was four times more likely to utilize youth-friendly SRH services in Ethiopia (AOR = 3.79; 95% CI:2.11–6.80). The heterogeneity test revealed high variability, I2 = 81.1 %, indicating high heterogeneity, so the random effect model was assumed in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change as a result of the sensitivity analysis (Figure 7).

The pooled effect of five studies [41, 46, 48, 52, 54] revealed that having ever experienced reproductive health problems were significantly associated with utilization of youth-friendly SRH services (AOR = 3.25; 95% CI:1.76–6.00). The high heterogeneity test revealed I2 = = 81.7 %, implying that a random effect model was used in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change significantly as a result of sensitivity analysis (Figure 7).

The pooled effect of five studies [34, 35, 37, 41, 47] showed that youth-friendly SRH services close to home were increased three times the odds of reproductive health service utilization in Ethiopia (AOR = 3.00; 95% CI:2.19–4.12). The heterogeneity test revealed low variability, I2 = 22.7 %, indicating low heterogeneity; thus, the random effect model was used in the analysis. The overall ORs did not change, according to the sensitivity analysis (Figure 7).

6. Discussion

Twenty-six studies with 16,246 participants were analyzed in this review to estimate youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization and determinant factors in Ethiopia. According to this meta-analysis, the national pooled prevalence of youth-friendly SRH service utilization was 42.73 % (95 % CI, 35.38 %–50.09 %). This review finding is low compared to Ethiopian efforts to improve youth-friendly RH services, including numerous multi-sectoral consultative meetings led by the MOH and line ministries, NGOs, UN Agencies, donors, technical organizations, and research institutions [21].

This review showed that grade levels 9-10 and 11-12 were strongly associated with utilizing youth-friendly SRH services. This could be because higher educational status contributed to the free sharing of SRH information with family, friends, or groups, and as their maturity increased, so did the demand for RH services [55]. Compared to adolescents aged 10 to 19, youths aged 20 to 24 years were strongly associated with utilizing SRH services. In addition, adolescent age groups of 15–19 years were associated with SRH service utilization compared to 10–14 years. As they get older, their maturity level rises, as do their sexual behaviours, and they engage in sex. The likelihood of RH service utilization increased to avoid unwanted pregnancy and HIV infection [56].

Youth-friendly SRH service close to home for youth and adolescents was strongly associated with RH service utilization. This is because health facilities are readily available and accessible in the surrounding area, allowing youths to use them conveniently and gain access to RH education [57]. Convenience working hours for utilization of RH services for youth were strongly associated with youth-friendly RH service utilization. This might be in the standard working time of health facilities; students or young people have spent most of their time at school or working on helping their partner. When health facilities are functional at the weekend and lunchtime, and in the evening, the probability of youths utilising the RH service increases[23].

Male sex is associated significantly with youth-friendly SRH service utilization. This may be due to cultural factors in the research field, where young females are often verbally and physically assaulted by males when they go alone. This fair limits their community participation. On the other hand, males are free to engage in society and have a low judgmental attitude from healthcare providers.

Discussion of SRH service with family, friends, and groups was strongly associated with youth-friendly SRH service utilization. Parent-adolescent sexuality communication is critical in informing young people about the risk and protective behaviours, which reduces their likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviours [58, 59]. Parents who are transparent about sexuality with their young children have more robust communication, which is crucial for preventing risky sexual activities like early sexual initiation, unwanted pregnancy, and other reproductive health issues [58].

Ever experience sexual activity and experience RH problems, especially pregnancy-related complications, were strongly associated with youth-friendly SRH service utilization. Since females exposed to sexual intercourse are more likely to have unintended pregnancies, STIs, and HIV and miss school due to pregnancy-related complications, they often use health facilities for family planning and voluntary counselling and testing for HIV testing. Furthermore, those with a history of RH illness are more likely to use RH services to avoid further suffering [60].

Two studies [37, 38] showed that youths who live with their partner increased utilization of SRH services than those who lived away from their family. In contrast, two studies [39, 40] found that youths living away from their families were significantly more likely to use youth-friendly SRH services. This could be because most Ethiopian teenagers are subjected to increased parental supervision, and most youths’ sexual relationships are hidden from their parents. As a result, access to RH services may be restricted. On the other hand, living with their parents increases the likelihood of discussion of RH problems and parental support for RH service use.

Three studies found that young people who had good knowledge about SRH issues [35, 36, 53] and five studies found that well-informed youth about SRH programs were more likely to use youth-friendly SRH services [36, 41, 44, 51, 52]. This is supported by a systematic analysis of a related study in Sub-Saharan Africa [61]. Other similar findings have been reported as the youth's lack of understanding of the importance of sexual and reproductive health care, and their lack of awareness of where to seek care may deter them from using youth-friendly SRH services [62, 63]. This might be because the high level of awareness and knowledge about RH service was more likely to use youth-friendly RH services. This might be because young people who are unaware or have not been informed about SRH may realistically fear the stigma associated with seeking SRH care.

This study also found that secondary school or higher maternal education levels strongly predict youth-friendly SRH service utilization. This might be because maternal education in life skills enables children to protect and promote their health and well-being. Maternal education about RH issues influences their children's ability to freely discuss sexual and reproductive issues and allows them to use RH services.

Youth who were involved in school clubs increased the odds of the utilization of SRH service. This may be because young people who receive SRH education at a school club have a greater understanding of RH issues and a better risk assessment of unsafe sex, unwanted pregnancy, and STI/HIV infections.

7. Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that youth-friendly SRH service utilization was low in Ethiopia. According to the results of this study, grade level 11–12, grade level 9–10, close to home SRH service, male sex, discussion of SRH service with family, friends, and or groups, ever experience sexual activity were significantly associated with youth-friendly SRH services. Similarly, maternal educational status secondary school and above, age 20-14 years, age 15–19 years, ever experience with RH problems, living with a partner, living alone, well informed about RH issues, knowledge about SRH, convenience working time for youth-friendly service, and participation in school club were associated with utilization of youth-friendly SRH service. This result highlights the need for governmental, non-governmental, and other stakeholders to develop an effective intervention in implementing youth-friendly SRH service utilization and promoting of the service to reduce SRH related problems.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Habtamu Gebrehana, Getachew Arage, Alemu Degu, Bekalu Getnet and Mulugeta Dile: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Worku Necho, Enyew Dagnew and Abenezer Melkie: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Tigist Seid, Minale Bezie and Gedefaye Nibret: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the original study's authors and publishers.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Sexual Health and its Linkages to Reproductive Health: an Operational Approach. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258738/9789241512886-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Universal health coverage. In: World Health Organization [website]. Geneva: WHO; no date (https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1, accessed 10 December 2020).

- 3.Fikree F.F., et al. Making good on a call to expand method choice for young people-Turning rhetoric into reality for addressing Sustainable Development Goal Three. Reprod. Health. 2017;14(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra-Mouli V., et al. Twenty years after International Conference on Population and Development: where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56(1):S1–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations . 2017. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabiru C.W., Izugbara C.O., Beguy D. The health and wellbeing of young people in sub-Saharan Africa: an under-researched area? BMC Int. Health Hum. Right. 2013;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geta M.B., Yallew W.W. Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Adv. Public Health. 2017;2017 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geary R.S., Gómez-Olivé F.X., Kahn K., Tollman S., Norris S.A. Barriers to and facilitators of the provision of a youth-friendly health services programme in rural South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tilahun M., et al. Health workers' attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health services for unmarried adolescents in Ethiopia. Reprod. Health. 2012;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olusanya B., et al. The burden and management of neonatal jaundice in Nigeria: a scoping review of the literature. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2016;19(1):1–17. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.173703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olusanya B.O., Osibanjo F.B., Slusher T.M. Risk factors for severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones N., Presler-Marshall E., Hicks J., Baird S., Chuta N., Gezahegne K. A Report on GAGE Ethiopia Baseline Findings. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence. 2019. Adolescent health, nutrition, and sexual and reproductive health in Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health . 2011. Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health. Blended Learning Module for the Health Extension Programme.http://labspace.open.ac.uk/file.php/6716/AYRH_Final_Print-ready_April_2011_.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute, E.P.H. and ICF . EPHI and ICF; Rockville, Maryland, USA: 2019. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dingeta T., Lemessa Oljira A.W., Berhane Y. Unmet need for contraception among young married women in eastern Ethiopia. Open Access J. Contracept. 2019;10:89. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S227260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birhanu B.E., et al. Predictors of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Publ. Health. 2019;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayanaw Habitu Y., Yalew A., Azale Bisetegn T. Prevalence and factors associated with teenage pregnancy, northeast Ethiopia, 2017: a cross-sectional study. J. Pregnancy. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/1714527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezmur H., Assefa N., Alemayehu T. Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in eastern Ethiopia: a community-based study. Int. J. Wom. Health. 2021;13:267. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S287715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ICAP at Columbia University . 2018. Ethiopia Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment.https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3511%E2%80%A2EPHIA-Summary-Sheet_v30.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comins C.A., et al. Vulnerability profiles and prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among adolescent girls and young women in Ethiopia: a latent class analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health M.o. Ministry of Health; 2016. National Adolescent and Youth Health Strategy (2016-2020) [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Adolescent And Youth Health Strategy (2016-2020).Federal Democratic Republic Of Ethiopia Ministry Of Health. October 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323525792 Avialable at. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain A., et al. 2017. Understanding Adolescent and Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health-Seeking Behaviors in Ethiopia: Implications for Youth Friendly Service Programming. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simegn A., et al. Youth friendly sexual and reproductive health service utilization among high and preparatory school students in Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0240033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute J.B. The Joanna Briggs Institute; Australia: 2014. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shea B., et al. 2020. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis Bias and Confounding Newcastle-Ottowa Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Contr. Clin. Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne J.A., Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval S., Tweedie R. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2000;95(449):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelagay A.A. 28th Annual Conference, 2016. 2017. Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among preparatory school students in Mecha district, northwest Ethiopia Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among preparatory school students. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feleke S.A., et al. Reproductive health service utilization and associated factors among adolescents (15–19 years old) in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate A.T., Ayisa A.A. Reproductive health services utilization and its associated factors among secondary school youths in Woreta town, South Gondar, North West Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurara A.M., et al. Vol. 2020. Nursing Practice Today; 2018. Reproductive Health Service Utilization and Associated Factors Among Adolescents at Public School in Adama Town East Shewa Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abajobir A.A., Seme A. Reproductive health knowledge and services utilization among rural adolescents in east Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayehu A., Kassaw T., Hailu G. Level of young people sexual and reproductive health service utilization and its associated factors among young people in Awabel District, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lejibo T.T., et al. Reproductive health service utilization and associated factors among female adolescents in Kachabirra District, South Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Am. J. Biomed. Life Sci. 2017;5(5):103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tlaye K.G., et al. Reproductive health services utilization and its associated factors among adolescents in Debre Berhan town, Central Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health. 2018;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wachamo D., et al. Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among College students at west Arsi zone in Oromia region, Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/3408789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim T.Y. 2020. Youth Friendly Services Utilization And Associated Factors Among Young People In Tehuledere District, Northeast Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ansha M.G., Bosho C.J., Jaleta F.T. Reproductive Health services utilization and associated factors among adolescents in Anchar District, East Ethiopia. J. Fam. Reprod. Health. 2017;11(2):110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bilal S.M., et al. Utilization of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Ethiopia–Does it affect sexual activity among high school students? Sex. Reproduct. Healthc. 2015;6(1):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.T T. 2017. Current Utilization Of Reproductive Health Services Andthe Role Of Peer Influence Among Undergraduate Students Of Wachamo University, Hosanna, Snnpr, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 45.T T. 2015. Assessment Of Reproductive Health Service Utlization And Associated Factors Among High School Youths In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abebe M., Awoke W. Utilization of youth reproductive health services and associated factors among high school students in Bahir Dar, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Open J. Epidemiol. 2014;2014 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fikadu A., et al. Youth friendly reproductive health service utilization and associated factors among school youths in Ambo town, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Am. J. Health Res. 2018;8(4):60–68. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kerbo A., et al. Youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors in Bale zone of Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. J. Wom. Health Reprod. Med. 2018;2(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gebreyesus H., Teweldemedhin M., Mamo A. Determinants of reproductive health services utilization among rural female adolescents in Asgede-Tsimbla district Northern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health. 2019;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0664-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gebreselassie B., et al. Assessment of reproductive health service utilization and associated factors among adolescents (15–19 Years old) in Goba town. Southeast Ethiop. 2015;3(4):203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Negash W., et al. Reproductive health service utilization and associated factors: the case of north Shewa zone youth, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016;25(Suppl 2) doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2016.25.2.9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Helamo D., et al. Utilization and factors affecting adolescents and youth friendly reproductive health services among secondary school students in Hadiya zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region, Ethiopia. Int. J. Publ. Health Sci. 2017;2(141):2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Motuma A., et al. Utilization of youth friendly services and associated factors among youth in Harar town, east Ethiopia: a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Binu W., et al. Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among secondary school students in Nekemte town, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health. 2018;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Napit K., et al. Factors associated with utilization of adolescent-friendly services in Bhaktapur district, Nepal. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2020;39(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41043-020-0212-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris J.L., Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;131:S40–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tilahun T., et al. Assessment of access and utilization of adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health services in western Ethiopia. Reprod. Health. 2021;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mekie M., et al. Parental communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and its associated factors among preparatory school students in Debre Tabor, Northcentral Ethiopia: institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayalew M., Mengistie B., Semahegn A. Adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues among high school students in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reprod. Health. 2014;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haile B., et al. Disparities in utilization of sexual and reproductive health services among high school adolescents from youth friendly service implemented and non-implemented areas of Southern Ethiopia. Arch. Publ. Health. 2020;78(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00508-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonas K., et al. Healthcare workers’ behaviors and personal determinants associated with providing adequate sexual and reproductive healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1268-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asare B.Y.-A., Aryee S.E., Kotoh A.M. Sexual behaviour and the utilization of youth friendly health Services: a cross-sectional study among urban youth in Ghana. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2020;13:100250. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godia P. MOH; Nairobi: 2010. Youth Friendly Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Provision in Kenya: what Is the Best Model; pp. 74–82. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.