1. Abstract

Background

Bile reflux gastropathy is caused by the backward flow of duodenal fluid into the stomach. A retrospective cohort study was performed to declare if the therapeutic biliary interventions cause bile reflux gastropathy, and to estimate its prevalence and risk factors, and to evaluate the gastric mucosa endoscopic and histopathologic changes.

Methods

62 patients, with epigastric pain and/or dyspeptic symptoms, were grouped into, Group 1: (34) patients that had undergone cholecystectomy and Group 2: (28) patients who had undergone at least one of the following procedures for the treatment of benign pathology: endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic stenting. Their ages ranged from 27 to 59 years. All participants had undergone gastroscopy for gastric aspirate analysis as well as gastric mucosa biopsy for histopathological examination.

Results

the prevalence of bile reflux gastropathy was (21.34%) after therapeutic biliary interventions with a P-value of 0.000. In both groups, diabetes, obesity, increased gastric bilirubin, and increased gastric pH were risk factors for bile reflux gastropathy (r = 0.27, 0.31, 0.68, 0.59 respectively), while age, sex, epigastric pain, heartburn, vomiting were mot.

Conclusion

bile reflux gastropathy is common after therapeutic biliary interventions being more among obese and diabetic patients.

Keywords: Bile reflux, Cholecystectomy, ERCP, Bilirubin

Highlights

-

•

Endoscopic and histologic findings, and elevated gastric aspirate bilirubin and pH, were diagnostic for biliary gastropathy.

-

•

Bile reflux gastropathy prevalence post- cholecystectomy and post-ERCP was 61.76% and 71.43% respectively.

-

•

Diabetes, obesity, increased gastric bilirubin, and increased gastric pH were risk factors for bile reflux gastritis.

1. Introduction

Bile reflux gastropathy is a pathological condition in the form of the backward flow of duodenal fluid that consists of bile, pancreatic juices, and secretions of the intestinal mucosa into the stomach and esophagus [1], causing mucosal lesions [2]. Bile acids, in combination with gastric acid, have been shown to cause bile reflux gastropathy symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, epigastric pain, etc.) [3].

Bile reflux gastropathy frequently occurs after gastric surgeries that damage the pyloric sphincter, (2) and after biliary surgeries and procedures as cholecystectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), endoscopic stenting, or choledochoduodenostomy that cause the sphincter of Oddi malfunction [4]. Bile gastropathy is a normal physiological event in a prolonged fasting period (primary bile reflux gastropathy) [5]. In non-responsive individuals to PPI medication, the total prevalence of biliary reflux was 68.7%. These people have acid and bile reflux at the same time and have never had biliary surgery [6].

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) became an increasingly popular modality for both the diagnosis and the treatment of biliary tract disorders [7]. It represents one of the most demanding and technically challenging procedures in gastrointestinal endoscopy, which must be performed effectively and safely by operators with substantial training and experience to maximize success and safety [8]. Cholecystectomy is a surgical operation of gallbladder removal. It can be performed either laparoscopically, using a video camera, or via an open surgical technique. Pain and complications caused by gallstones are the most common reasons for cholecystectomy [9].

The study hypothesized that therapeutic biliary procedures may followed by biliary gastropathy and aimed at identifying the prevalence and possible risk factors for biliary gastropathy after therapeutic biliary procedures.

2. MATERIALS and METHODS

2.1. Subjects

After The Zagazig University Hospital institutional and ethical committee approved this study protocol (Approval Date: 1.1.2018 and Approval Number 4238), a retrospective cohort study was performed from January 1, 2018, to December 15, 2020. Informed consent was taken from all patients. The article has been registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov research registry (NCT05131802) and the work has been also reported in line with the STROCSS criteria [10].

The study started with 288 patients who were admitted to Zagazig university hospitals, Zagazig, Egypt with inclusion criteria of refractory epigastric pain and dyspeptic symptoms with a history of poor response to prokinetics, mucosa-protective medicines, H2-blockers and/or proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), after therapeutic biliary interventions. The patients enrolled in the study stated that they had no such complaints before the biliary interventions. A total of 96 patients were eliminated because of the study exclusion criteria or because they refused to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or cardiovascular status, other causes of biliary diseases (CBD strictures, and hepatolithiasis), structural abnormalities of the esophagus, stomach, or small intestine, patients who underwent bariatric surgery out of the scope of the study, patients on long-term non-steroidal analgesics, patients on oral contraceptive drugs, and H. pylori stool antigen-positive patients. Gastroscopy was performed on 192 patients who met the study inclusion criteria and accepted to participate in the study. Another 130 patients were eliminated because of the presence of findings other than bile gastritis such as hiatus hernia, biliary dyskinesia, and psychosomatic patients. Hence, the study was performed on 62 patients who were diagnosed grossly as gastritis for a full assessment of the cause of gastritis. Their age ranged from 24 to 67 years with a mean age ±SD of 41.6 ± 10.01. They were 35 Female (56.5%) and 27 Male (43.5%). Patients were split into two groups; Group 1: (Postcholecystectomy group) which included (34) patients that had undergone cholecystectomy. Their ages ranged from 24 to 67 years with mean age ±SD of 43.53 ± 11.45. They were 20 Female (58.8%) and 14 Male (41.2%). Group 2: (Biliary intervention group) which included (28) patients who had undergone at least one of the following procedures for the treatment of benign pathology: endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and endoscopic stenting. Their ages ranged from 27 to 59 years with mean age ±SD of 39.25 ± 7.47. They were 15 Female (53.6%) and 13 Male (46.4%).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Diagnostic techniques of bile reflux gastropathy

2.2.1.1. Gastroscopy

Esophageal mucosa alterations as erythema, presence of bile into the esophagus, edema, GERD (Gastroesophageal reflux disease), incompetent cardia, and petechiae were recorded using the gastroscope (Olympus single-channel CLK-4). Gastric mucosa alterations as erythema, bile existence in the stomach, gastric folds thickening, erosions, and petechiae were also recorded.

2.2.1.2. Histopathology

Multiple biopsies were taken from gastric mucosa via disposable flexible endoscopic biopsy forceps, 2 cup-shaped jaws with a central spike (Boston Scientific®) for histopathological study.

2.2.1.3. Gastric aspirate analysis

Via Triple Lumen ERCP Cannula, 5.5 F (Boston Scientific®), immediately after insertion of the scope into the stomach, 5 mL of gastric fluid was aspirated through the suction channel of the endoscope and collected in a sterile trap placed in the suction line, to be sent for analysis. Quantitative determination of gastric aspirate total bilirubin level was performed (Gen.3® kit and Cobas 8000 analyzer). The pH monitoring of gastric aspirate was performed during the gastroscopy just after collection with a glass electrode pH meter (Adwa®).

2.2.2. Statistical analysis

The obtained data were statistically analyzed using SPSS program version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (‾X ± SD) in quantitative variables, and numbers and percentages for qualitative variables. Independent-Sample (T) test was used to compare quantitative variables means of two groups. Chi-Square test (X2) was used to compare qualitative variable means. The results were considered statistically significant if the P-value was <0.05. Correlation between variables was done using the Person correlation coefficient (r).

3. Results

The demographic data of the patients with bile reflux gastropathy in group 1 ranged from 24 to 67 years with mean age ± SD of 43.53 ± 11.45 years. Bile reflux gastropathy was noted in 14 males (41.2%) and 20 females (58.8%). The demographic data of the patients with bile reflux gastropathy in group 2 ranged from 27 to 59 years with mean age ±SD of 39.25 ± 7.47. Bile reflux gastropathy was noted in 13 males (46%) and 15 females (53.6%).

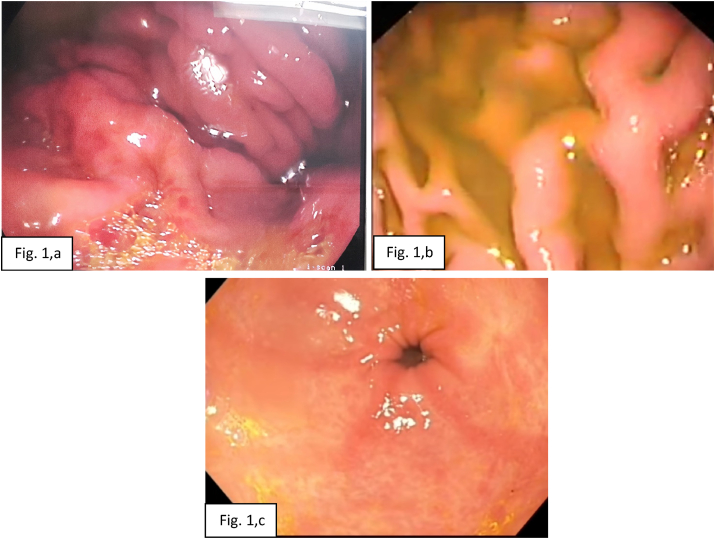

In group 1, the endoscopic findings of esophageal mucosa included GERD in 22 cases (64.7%), incompetent cardia in 12 cases (35.3%), and mucosal changes in 10 cases (29.4%). While, the endoscopic findings of gastric mucosa included erythema in 18 cases (52.9%), presence of bile in 17 cases (50%), thick gastric fold in 12 cases (35.3%), erosions in 8 cases (23.5%), edema in 8 cases (23.5%), and petechiae in 7 cases (20.6%). In group 2, the endoscopic findings of esophageal mucosa included GERD in 12 cases (42.9%), mucosal changes in 11 cases (39.3%), and incompetent cardia in 7 cases (25%). While, the endoscopic findings of gastric mucosa included erythema in 18 cases (64.3%), presence of bile in 16 cases (57.1%), thick gastric fold in 13 cases (46.4%), petechiae in 8 cases (28.6%) erosions in 6 cases (21.4%), and edema in 5 cases (17.9%) (Table 1, Fig. 1, a-c).

Table 1.

Endoscopic findings of our study.

| Parameter | Group No. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 |

Group 2 |

||||

| No. of case | % | No. of case | % | ||

| Esophageal | GERD | 22 | 64.7% | 12 | 42.9% |

| incompetent cardia | 12 | 35.3% | 7 | 25% | |

| Fluid regurgitation | 15 | 44.1% | 8 | 28.6% | |

| Mucosal changes | 10 | 29.4% | 11 | 39.3% | |

| Gastric | Erythema of gastric mucosa | 18 | 52.9% | 18 | 64.3% |

| Presence of bile | 17 | 50% | 16 | 57.1% | |

| Thick gastric fold | 12 | 35.3% | 13 | 46.4% | |

| Erosions | 8 | 23.5% | 6 | 21.4% | |

| Petechiae | 7 | 20.6% | 8 | 28.6% | |

| Edema | 8 | 23.5% | 5 | 17.9% | |

GERD; Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Fig. 1.

Upper GIT endoscopic picture showing (a): gastric petechiae and presence of bile in the stomach, (b): thinking of gastric folds and presence of bile in the stomach, (c): antral gastritis with mucosal erythema and erosions with the presence of bile in the stomach.

In our study, bilirubin levels in gastric aspirate in group 1 ranged from 0.15 to 10.40 mg/dl (mean 3.60 ± 3.55 mg/dl). The gastric aspirate pH of such group ranged from 5.5 to 8 (mean 6.94 ± 0.78). Meanwhile, bilirubin levels in gastric aspirate in group 2 ranged from 0.45 to 19.15 mg/dl (mean 7.43 ± 5.70 mg/dl). The gastric aspirate pH of such group ranged from 5.50 to 8 (mean 7.17 ± 0.88).

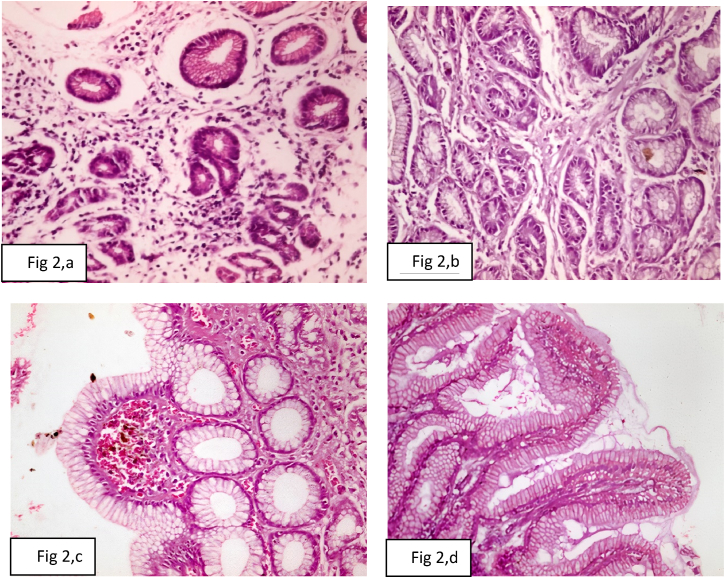

The histopathological finding of gastric mucosa biopsies in group 1 included chronic inflammation in 18 cases (52.9%), foveolar hyperplasia in 11 cases (32.3%), chronic Atrophic gastritis in 9 cases (26.4%), bile stasis in 8 cases (23.5%), interstitial inflammation in 8 cases (23.5%), edema in 7 cases (20.6%), intestinal metaplasia in 6 cases (17.6%), and acute inflammation in 2 cases (5.9%). The histopathological finding of gastric mucosa biopsies in group 2 included chronic inflammation in 18 cases (64.3%), foveolar hyperplasia in 13 cases (46.4%), bile stasis in 9 cases (32.1%), intestinal metaplasia in 8 cases (28.6%), chronic atrophic gastritis in 6 cases (21.4%), interstitial inflammation in 6 cases (21.4%), edema in 6 cases (21.4%), and acute inflammation in 2 cases (7.1%) (Table 2, Fig. 2, a-d).

Table 2.

Gastric mucosa histopathological findings of our study.

| Parameter | Group No. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 |

Group 2 |

|||

| No. of case | % | No. of case | % | |

| Chronic inflammation | 18 | 52.9% | 18 | 64.3% |

| Acute inflammation | 2 | 5.9% | 2 | 7.1% |

| Chronic Atrophic gastritis | 9 | 26.4% | 6 | 21.4% |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 6 | 17.6% | 8 | 28.6% |

| Bile stasis | 8 | 23.5% | 9 | 32.1% |

| Interstitial inflammation | 8 | 23.5% | 6 | 21.4% |

| Foveolar hyperplasia | 11 | 32.3% | 13 | 46.4% |

| Edema | 7 | 20.6% | 6 | 21.4% |

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of (a): chronic atrophic gastritis with per glandular fibrosis, chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and mild dysplasia (H&E X400), (b): chronic gastritis with per glandular fibrosis and mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate (H&E X400), (c): chronic gastritis with focal bile stasis (H&E X400), (d): chronic gastritis with diffuse intestinal metaplasia and interstitial inflammation (H&E X400).

As regards the presence of bile reflux gastropathy, it was present in 21 cases in group 1 patients with a percentage of (61.76%). However, it was present in 20 cases in group 2 patients with a percentage of (71.43%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of bile reflux gastropathy and non- bile reflux gastropathy in our study.

| Parameter | Group 1 |

Group 2 |

X2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 34 | % | N = 28 | % | |||

| bile reflux gastropathy | 21 | 61.76 | 20 | 71.4 | 0.64 | 0.59 |

| Non- bile reflux gastropathy | 13 | 38.24 | 8 | 28.6 | ||

The risk factors for bile reflux gastropathy in group 1 included increased gastric bilirubin (17cases), and alkaline gastric pH (20cases), diabetes (14 cases), obesity (17 cases), and Helicobacter pylori infection (3 cases). However, the risk factors in group 2 included increased gastric bilirubin (19 cases), and alkaline gastric pH (20 cases), diabetes (13 cases), obesity (17 cases), and Helicobacter pylori infection (4 cases).

The study revealed statistically significant positive correlations between increased gastric bilirubin, increased gastric aspirate pH, diabetes, obesity, and the presence of bile reflux gastropathy in both studied groups (r = 0.68, 0.59, 0.27, 0.31 respectively). There were no correlations between age, sex, epigastric pain, heartburn, vomiting, and the presence of bile reflux gastropathy in both groups of our study (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between risk factors and presence of bile reflux gastropathy in studied groups.

| Bile Reflux Gastropathy |

||

|---|---|---|

| r | P | |

| BMI | 0.31b | 0.16 |

| Gastric pH | 0.59a | 0.00 |

| Gastric Bilirubin | 0.68a | 0.00 |

| RBS | 0.27b | 0.03 |

| Epigastric pain | 0.07 | 0.57 |

| Heart burn | −0.10 | 0.43 |

| Vomiting | −0.007 | 0.96 |

| Age | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| sex | 0.15 | 0.25 |

BMI: Body mass index, RBS: Random blood sugar, GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

4. Discussion

Bile reflux gastropathy is a disease characterized by upper abdominal pain, frequent heartburn, nausea, and vomiting of bile. Such disease appears to be caused by the backward flow of duodenal fluid into the stomach and esophagus. This fluid contains bile, pancreatic juices, and duodenal secretion [1]. The diagnosis was based on clinical findings, pH monitoring of the aspirated gastric juice on the assumption that the bile reflux would cause an increase of pH over 7 as a result of the alkaline nature of duodenal juice [11], with the aid of endoscopic and pathologic findings [12].

In this study, the esophageal endoscopic findings were GERD, incompetent cardia, fluid regurgitation, and mucosal changes. The most frequent esophageal endoscopic finding was GERD in both groups 1 and 2 with the percentage of (64.7%) and (42.9%) respectively. However, the gastric endoscopic findings were erythema of gastric mucosa, presence of bile, thick gastric fold, erosions, petechiae, and edema (Fig. 1a–c). The most frequent gastric endoscopic finding was erythema of gastric mucosa in both groups 1 and 2 with the percentage of (52.9%) and (64.3%) respectively (Table 1). Such findings were similar to that of former studies. Martamala and Rani diagnosed bile reflux gastropathy endoscopically, based on the presence of bile in the gaster, with adherence of bile on the gastric mucous membrane in the form of crusts and changes in the mucous membrane that becomes hyperemic, frail, and erosive [13]. In a Romanian endoscopic study of bile reflux gastropathy, the endoscopic gastric mucosa changes were erythema, bile existence in the stomach, over thickening of gastric folds, erosions, atrophic mucosa, petechiae, intestinal metaplasia, and polyp. [2] Al-Bayati and Alnajjar conducted that the endoscopic findings were erythema, gastric erosion, thickening of gastric folds, and gastric atrophy. The most common gastric endoscopic finding was erythema of the gastric mucosa (50%). All the patients had bile in the stomach [12].

Shenouda et al. [14] found that mean normal bilirubin levels in gastric aspirate was 1.3 mg/dl. The normal pH of gastric juice was 1.5–3.5 in the human stomach lumen [15]. In our study, the alkaline gastric aspirate in both groups 1 and 2 (6.94 ± 0.78 and 7.17 ± 0.88 respectively) with a high level of gastric bilirubin level (3.60 ± 3.57 and 7.43 ± 5.70 respectively) was supposed to be the cause of esophageal and gastric mucosal damage although the exact mechanisms were still unclear [16]. Some studies indicated that interaction of bile acid, a component of bile; with M3 muscarinic receptor subtype expressed in chief cells might contribute to mucosal damage, manifested as active inflammation, intestinal metaplasia, glandular atrophy and focal hyperplasia, and other pathophysiological consequences of bile reflux. [17] Apoptosis and redox reactions had been reported to be associated with bile acid-induced gastritis. [18] Some studies reported that bile acids and other contents of the duodenum would act synergistically in the development of chronic gastritis with gastric acid and Helicobacter pylori infection. [16]

The most frequent histopathological finding in our study was chronic inflammation in both groups 1 and 2 with the percentage of (52.9%) and (64.3%) respectively. However, the least frequent histopathological finding was acute inflammation in both groups 1 and 2 with the percentage of (5.9%) and (7.1%) respectively (Table 2). Our results agreed with a previous study that proved that the histopathological changes of tissues samples were chronic gastritis, foveolar hyperplasia, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, acute gastritis, chronic atrophic gastritis, polyps, benign ulcers, and edema. The most frequent histopathological finding was chronic inflammation (84.06%) [2]. The histopathologic changes due to bile reflux gastropathy in children were characterized by chronic inflammation with foveolar hyperplasia in both the gastric corpora and antrum, vascular congestion, edema of lamina propria, and smooth muscle hyperplasia [19].

In our study, bile reflux gastropathy was present in (21) cases out of the (34) cases and in (20) out of (28) cases in group 1 and group 2 respectively (Table 3). The prevalence of bile reflux gastropathy was (61.76%) in group 1, while it was (71.43%) in group 2. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of bile reflux after therapeutic biliary interventions was 60% [20].

Our study showed that there were statistically significant positive correlations between obesity, increased gastric aspirate pH, increased gastric bilirubin, RBS, and bile reflux gastropathy occurrence in both groups. Such findings went with that of the former studies. Obesity was a risk factor for bile reflux gastropathy [21]. Deenadayalu et al. [22] demonstrated a significantly higher rate of post-ERCP complications in obese patients (BMI≥30 kg/m2) in comparison to overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2), normal-weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2), and underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2) patients. Shenouda et al. [14] declared that increased gastric aspirate bilirubin level and pH are confirmatory tools to diagnose biliary gastropathy with a significant relationship between the level of gastric bilirubin and the degree of inflammation. The gastric bilirubin level above 20 mg/dL could indicate severe esophagitis, erosive gastritis, or gastroesophageal metaplastic changes. In fact, more severe biliary gastritis was associated with higher bilirubin levels in the gastric aspirates. [23]

Diabetes mellitus was considered a risk factor for bile gastritis [2]. Barakat et al. [5] reported that diabetes mellitus might be considered a risk factor for primary biliary gastritis. Prevalence of type II diabetes mellitus was associated with gastroduodenal dysmotility. [24] Diabetes gastroparesis was a condition where persistent hyperglycemia, in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, could cause Vagus nerve damage, which was responsible for proper gastric movement resulting in delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction. [25] Severe bile reflux gastropathy was a consequence of diabetes gastroparesis [26,27].

Our study showed that there were no correlations between age, sex, epigastric pain, heartburn, vomiting, and the presence of bile reflux gastropathy (Table 4). A few previous research had looked into the relationship between age and biliary gastritis. Byrne et al. [28] stated that there was no evidence of a connection between age and bile reflux gastropathy. Bollschweiler et al. [29] also could not prove any significant difference between the patient's age and occurrence of bile reflux gastropathy.

In our study, histopathological examination of gastric mucosa revealed chronic atrophic gastritis showing per glandular fibrosis, chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and mild dysplasia (Fig. 2, a), chronic gastritis showing per glandular fibrosis and mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2, b), chronic gastritis showing focal bile stasis (Fig. 2, c), and chronic gastritis showing diffuse intestinal metaplasia and interstitial inflammation (Fig. 2, d). The former studies reported histopathological alterations because of bile gastritis similar to our findings in form of chronic gastric mucosa inflammation, lamina propria edema, foveolar hyperplasia, antral atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia [30]. Vere et al. [2] observed chronic gastritis, foveolar hyperplasia, intestinal metaplasia, gastric dysplasia, acute inflammation, chronic atrophic gastritis, polyps, benign ulcers, and edema. The histologic alterations owing to bile reflux gastritis in form of foveolar hyperplasia, edema, smooth muscle fibers in the lamina propria, and paucity of acute or chronic inflammatory cells were similar to those seen in chemical (reactive) gastritis [24].

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Therapeutic biliary interventions (group 1: cholecystectomy) and (group 2: ERCP) cause bile reflux gastropathy with the prevalence of (61.76%) in group 1 and (71.43%) in group 2. Diabetes, obesity, increased gastric bilirubin, and increased gastric pH were risk factors for bile reflux gastropathy in both groups. However, there were no correlations between age, sex, epigastric pain, heartburn, vomiting, and the presence of bile reflux gastropathy in both groups.

Patients diagnosed with bile reflux gastropathy were advised for lifestyle changes such as weight loss, avoiding GERD triggers, waiting at least 3 hours after eating before laying down, head of the bed elevation, and smoking cessation. Medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-type 2 receptor blockers (H2RBs) might be used if patients' symptoms persist. Patients with bile reflux gastropathy are often treated similarly to those with classic GERD because there are no formal guidelines for treating them. PPIs, H2RBs, prokinetics (metoclopramide), and baclofen (to reduce relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter) are some of the treatment possibilities. It's also crucial to go over a patient's medication list and minimize drugs like opioids and anticholinergics that can decrease gastroduodenal motility. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), cholestyramine, misoprostol, and sucralfate have all been researched, but there isn't enough evidence to recommend them [24].

Study limitations

The limitation of our study was the relatively small final number of fully investigated patients, owing to numerous exclusion of patients besides patients who refused to participate.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from Zagazig University Scientific Research and Publications Ethics Committee (Approval Date: 1.1.2018 and Approval Number 4238). After a thorough description of the study's benefits, each study participant gave verbal informed consent. Anyone who did not want to participate in the study was told that they had the right to do so at any time. Confidentiality was ensured by keeping personal identification information private and storing completed surveys and findings in a secure location.

Fund

None.

Authors' contributions

All authors the concept and design of the study; Amira Othman, Amal Dwedar, and Hany ElSadek data acquisition; Amira Othman statistical analysis; Amira Othman, Hesham Radwan, and Abeer Fikry interpreted the results; Amira Othman and Hany ElSadek analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Registration of research studies

Trial registry: ClinicalTrials.gov.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: NCT05131802.

Guarantor

Amira Ahmed Othman

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethics committee approved

The Zagazig University Scientific Research and Publications Ethics Committee approved the study (Approval Date: 1.1.2018 and Approval Number 4238).

Declaration of competing interest

None for all authors.

Acknowledgement

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.103168.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Eldredge T.A., Myers J.C., Kiroff G.K., Shenfine J. Detecting bile reflux—the enigma of bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018;28(2):559–566. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vere C., Cazacu S., Comănescu V., Mogoantă L., Rogoveanu I., Ciurea T. Endoscopical and histological features in bile reflux gastritis. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2005;46(4):269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun D., Wang X., Gai Z., Song X., Jia X., Tian H. Bile acids but not acidic acids induce Barrett's esophagus. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8(2):1384–1392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuran S., Parlak E., Aydog G., Kacar S., Sasmaz N., Ozden A., Sahin B. Bile reflux index after therapeutic biliary procedures. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barakat E.A., Abbas N.F., El-Kholi N.Y. Primary bile reflux gastritis versus Helicobacter pylori gastritis: a comparative study. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2018;30(1):23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monaco L., Brillantino A., Torelli F., Schettino M., Izzo G., Cosenza A., Di Martino N. Prevalence of bile reflux in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients not responsive to proton pump inhibitors. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG. 2009;15(3):334–338. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrasekhara V., Khashab M.A., Muthusamy V.R., Acosta R.D., Agrawal D., Bruining D.H., Eloubeidi M.A., Fanelli R.D., Faulx A.L., Gurudu S.R. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017;85(1):32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjiconstanti A.C., Messaris G.A., Thomopoulos K.C., Panayiotakis G.S. Patient radiation doses in therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in Patras and the key role of the operator. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 2017;177(3):243–249. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncx037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham S., Rivero H.G., Erlikh I.V., Griffith L.F., Kondamudi V.K. Surgical and nonsurgical management of gallstones. Am. Fam. Physician. 2014;89(10):795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha R., Abdall-Razak A., Crossley E., Dowlut N., Iosifidis C., Mathew G. The STROCSS 2019 guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2019;72:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckxstaens G.E., Smout A. Systematic review: role of acid, weakly acidic and weakly alkaline reflux in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2010;32(3):334–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Bayati S., Alnajjar A.S. Evaluation of the gastrointestinal clinical, endoscopic, and histological findings in patients with bile reflux diseases: a cross-sectional study. Mustansiriya Med. J. 2019;18(1):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martamala R., Rani A.A. The pathogenesis and diagnosis of bile reflux gastropathy. Indones. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Dig. Endosc. 2001;2(1):14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenouda M.M., Harb S.E., Mikhail S.A., Mokhtar S.M., Osman A.M., Wassef A.T., Rizkallah N.N., Milad N.M., Anis S.E., Nabil T.M. Bile gastritis following laparoscopic single anastomosis gastric bypass: pilot study to assess significance of bilirubin level in gastric aspirate. Obes. Surg. 2018;28(2):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marieb E., Hoehn K. Pearson Education; 2018. Human Anatomy & Physiology. 9780134580999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuhisa T., Tsukui T. Relation between reflux of bile acids into the stomach and gastric mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia in biopsy specimens. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2011:217–221. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park M.J., Kim K.H., Kim H.Y., Kim K., Cheong J. Bile acid induces expression of COX-2 through the homeodomain transcription factor CDX1 and orphan nuclear receptor SHP in human gastric cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(12):2385–2393. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y., Watanabe T., Tanigawa T., Machida H., Okazaki H., Yamagami H., Watanabe K., Tominaga K., Fujiwara Y., Oshitani N. Bile acids induce cdx2 expression through the farnesoid x receptor in gastric epithelial cells. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2009;46(1):81–86. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.09-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang P., Cui Y., Li W., Ren G., Chu C., Wu X. Diagnostic accuracy of diffusion-weighted imaging with conventional MR imaging for differentiating complex solid and cystic ovarian tumors at 1.5 T. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto N. Duodenogastric reflux after biliary procedure. Open Access Libr. J. 2014;1(7):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maguilnik W. Neumann, Sonnenberg A., Genta R. Reactive gastropathy is associated with inflammatory conditions throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2012;36(8):736–743. doi: 10.1111/apt.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deenadayalu V.P., Blaut U., Watkins J.L., Barnett J., Freeman M., Geenen J., Ryan M., Parker H., Frakes J.T., Fogel E.L. Does obesity confer an increased risk and/or more severe course of post-ERCP pancreatitis?: a retrospective, multicenter study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008;42(10):1103–1109. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318159cbd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lasheen M., Mahfouz M., Salama T., Salem H.E.-D.M. Biliary reflux gastritis after mini gastric bypass: the effect of Bilirubin level. 2019;3:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCabe M.E., Dilly C.K. New causes for the old problem of bile reflux gastritis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;16(9):1389–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petri M., Singh I., Baker C., Underkofler C., Rasouli N. Diabetic gastroparesis: an overview of pathogenesis, clinical presentation and novel therapies, with a focus on ghrelin receptor agonists. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2021;35(2):107733. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roses R.E., Fraker D.L. Gastrointestinal Surgery; Springer: 2015. Bile Reflux and Gastroparesis; pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weston A., Menguer R., Giordani D., Cereser C. A severe alkaline gastritis in type 1 diabetes gastroparesis: a case report. J. Gastrointest. Dig. Syst. 2017;7(540):2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrne J.P., Romagnoli R., Bechi P., Attwood S.E., Fuchs K.H., Collard J.-M. Duodenogastric reflux of bile in health: the normal range. Physiol. Meas. 1999;20(2):149–158. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/20/2/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bollschweiler E., Wolfgarten E., Pütz B., Gutschow C., Hölscher A.H. Bile reflux into the stomach and the esophagus for volunteers older than 40 years. Digestion. 2005;71(2):65–71. doi: 10.1159/000084521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genta R.M. Elsevier; 2005. Differential Diagnosis of Reactive Gastropathy, Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology; pp. 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article.