Abstract

The yeast CUP1 gene is activated by the copper-dependent binding of the transcriptional activator, Ace1p. An episome containing transcriptionally active or inactive CUP1 was purified in its native chromatin structure from yeast cells. The amount of RNA polymerase II on CUP1 in the purified episomes correlated with its transcriptional activity in vivo. Chromatin structures were examined by using the monomer extension technique to map translational positions of nucleosomes. The chromatin structure of an episome containing inactive CUP1 isolated from ace1Δ cells is organized into clusters of overlapping nucleosome positions separated by linkers. Novel nucleosome positions that include the linkers are occupied in the presence of Ace1p. Repositioning was observed over the entire CUP1 gene and its flanking regions, possibly over the entire episome. Mutation of the TATA boxes to prevent transcription did not prevent repositioning, implicating a chromatin remodeling activity recruited by Ace1p. These observations provide direct evidence in vivo for the nucleosome sliding mechanism proposed for remodeling complexes in vitro and indicate that remodeling is not restricted to the promoter but occurs over a chromatin domain including CUP1 and its flanking sequences.

Regulation of gene expression is best understood in living cells, where access to promoters and other regulatory elements is generally restricted by chromatin structure. Mechanisms have evolved to render these accessible at the appropriate moment (17, 60), including (i) regulated posttranslational modifications of the core histones, particularly acetylation, which alter nucleosome structure; (ii) remodeling of specific regions of chromatin by multisubunit complexes which use ATP to disrupt, displace, or slide nucleosomes; (iii) regulated nucleosome positioning (48); and (iv) contributions of other chromatin proteins.

An ideal approach to studying these interactions would be to examine native chromatin structures in vitro by using the sophisticated techniques available for analysis of reconstituted chromatin and relate these to events in vivo. The main concerns are purity and the amounts of material available. The use of small episomes with high copy number facilitates the separation of large chromosomal fragments from the gene of interest, e.g., simian virus 40 minichromosomes (14). Budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) offers a source of minichromosomes in the form of plasmids, with the advantage that a model gene can be chosen and studied in the context of its molecular genetics (13, 20, 45).

CUP1 encodes a copper metallothionein responsible for protecting yeast cells from the toxic effects of copper (7, 23). It was chosen as a model gene because its regulation is well understood and relatively simple, increasing the likelihood that its activity can be reconstituted in vitro. In the absence of toxic concentrations of copper, CUP1 is not required for growth (18). It is strongly induced when copper ions enter the cell and bind to the N-terminal domain of the transcriptional activator Ace1p (also called Cup2p), which folds and binds specifically to upstream activating sequences (UASs) in the CUP1 promoter (6, 16). Transcription of CUP1 is activated via the C-terminal acidic activation domain (16). Thus, the signal transduction pathway is known in some detail. The only other transcription factor that influences CUP1 expression directly is heat shock factor (33). Current models for transcriptional activation are highly complex, invoking requirements for many proteins (51). However, CUP1 can be induced in vivo in the absence of many of the basal transcription factors: TATA-binding protein (TBP) has been detected at the CUP1 promoter in vivo (25, 31), but induction is independent of TFIIA (32, 42), TFIIE (46), the Kin28 CTD kinase of TFIIH, and some components of the mediator, but not others (28, 29, 36). Furthermore, Ace1p activates transcription independently of most of the TAFs (37). Thus, CUP1 appears to be an example of simplified regulation (27).

We are interested in the process by which a gene in its natural chromatin context is activated for transcription. Here we describe the native chromatin structures of the transcriptionally active and inactive forms of CUP1 in a small episome purified from yeast cells. Activation of CUP1 is accompanied by a gene-wide repositioning of nucleosomes, which requires the presence of Ace1p but is independent of transcription, providing evidence for an activator-dependent remodeling activity that moves nucleosomes on CUP1 and its flanking sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of yeast strains and plasmids.

The CUP1 locus was deleted from BJ5459 (MATa cir+ ura3-52 trp1 lys2-801 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb1Δ1.6R can1 GAL) (21) (Yeast Genetic Stock Center, Berkeley, Calif.) by transformation with the 4.3-kb Bst1107I-SwaI fragment from pΔCup3, with LEU2 flanked by CUP1 locus flanking sequences. pΔCup3: The 828-bp HindIII fragment from cosmid ATCC 71209 containing sequence flanking the CUP1 locus was inserted at the HindIII site of pNEB193 (New England Biolabs) to obtain pΔCup1A. The 1.8-kb DraI fragment from cosmid ATCC 70887 containing sequence on the other side of CUP1 was inserted at the SmaI site in pΔCup1A to obtain pΔCup2A. LEU2 as a 2.0-kb BstYI-SalI fragment from pOF4 (30) (gift of J. Thorner) was inserted into pΔCup2A BamHI/SalI to give pΔCup3. This strain was cured of the 2μm circle plasmid to obtain YDCcup1Δ2 as described previously (3). TRP1 ARS1 as a 1,453-bp HindIII fragment from pTB-B9 (54) (gift of A. Dean) was inserted at the HindIII site of pGEM13zf(+) (Promega), oriented such that ARS1 is closest to the NotI site in the vector, to give pGEM-TRP1ARS1. CUP1 was obtained either as a 1,998-bp KpnI fragment containing the entire CUP1 repeat or as a 925-bp KpnI-NsiI fragment containing just CUP1 from YEp(CUP1)2A (ATCC 53233) and inserted into pUC19 cut with KpnI only or KpnI and PstI to give pCP1A (with CUP1 closest to the XbaI site in the vector) and pCP2, respectively. A 1,060-bp SphI-PvuII CUP1 fragment from pCP2 was inserted into pSP72 (Promega) SphI/PvuII to give pSP72-CUP1. A 1,015-bp EcoRI CUP1 fragment from pSP72-CUP1 was inserted at the EcoRI site in pGEM-TRP1 ARS1 to obtain pGEM-TAC(+), such that CUP1 is transcribed in the opposite direction to TRP1. pGEM-TAC(−) was obtained by cutting pGEM-TAC(+) with HindIII and religating to obtain the opposite orientation. TAC DNA as a 2,468-bp linear HindIII fragment from pGEM-TAC was circularized with ligase and used to transform YDCcup1Δ2. pGEM-TAC with both TATA boxes mutated was constructed by PCR-based mutagenesis: the proximal TATA box, TTATAA, was converted to CCCGGG; the distal TATA box, TATAAA, was converted to GGGCCC. An ace1Δ strain with TAC was constructed as follows. A 1,492-bp SmaI-HindIII ACE1 fragment from pRI-3 (gift of S. Hu and D. Hamer) (16) was inserted into pUC19 SmaI/HindIII to give pUC-ACE1. A BstZ17I-MscI fragment containing the ACE1 open reading frame (ORF) was replaced with URA3 to give pUC-ACE1ΔURA3. YDCcup1Δ2::TAC was transformed with the XbaI-HindIII fragment from pUC-ACE1ΔURA3. The replacement of ACE1 with URA3 was confirmed by Southern blotting. The copy number of TAC was determined by phosphorimager quantitation of the ratio of linearized TAC to chromosomal BglII fragment containing TRP1 in Southern blots of BglII digests of genomic DNA, using the 238-bp HindIII-BglII fragment from TAC as a probe.

Purification of minichromosomes.

The protocol is based on our previous method (3) with alterations resulting in increased yield, reflecting a systematic analysis of losses of TAC at each stage by quantitative Southern blot. Cells were grown at 30°C in synthetic complete medium lacking tryptophan to late log phase in flasks or in a fermenter and stored at −80°C. Cells (2.6 g) were thawed in 50 ml of spheroplasting medium (SM) (6.7 g of yeast nitrogen base with ammonium sulfate and without copper sulfate (Bio101) per liter, 2% d-glucose, 0.74 g of CSM-trp (Bio101) per liter, 1 M d-sorbitol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) with 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and warmed to 30°C for 15 min, with swirling. Lytic enzyme (120 mg) (Sigma L-4025; 1,000 U/mg) was dissolved in 3 ml of SM and added to the cells. Spheroplasting was followed by diluting aliquots of cells into 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and measuring A600. When the A600 reached 5% of the starting value, in about 20 min, spheroplasts were collected (7,500 rpm, 5 min, Sorvall SS34 rotor, 4°C), washed twice with 25 ml of SM (no 2-ME) and resuspended in 50 ml of prewarmed SM with or without 5 mM CuSO4. Spheroplasts were incubated at 30°C for 30 min at 225 rpm, collected as described above, and washed with 25 ml of cold 1 M d-sorbitol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Spheroplasts were lysed by vigorous resuspension with a pipette in 40 ml 18% (wt/vol) Ficoll 400, 40 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.5 [adjusted with phosphoric acid]), with 5 mM 2-ME, 0.1 mM AEBSF [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride], 5 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 15 μg of pepstatin A per ml. Two step gradients were used: 20 ml of lysate layered over 15 ml of 7% (wt/vol) Ficoll–20% (vol/vol) glycerol–40 mM potassium phosphate–1 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.5), with additions as described above, and spun (14,000 rpm, 30 min, SS34 rotor, 4°C). Each nuclear pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–5 mM Na-EDTA with additions as described above. Forty microliters of RNase (Qiagen; DNase free; 100 mg/ml) was added to each resuspension, left for 30 min on ice, and spun (10,000 rpm, 5 min; SS34; 4°C). The cloudy supernatants, containing the minichromosomes, were applied to a 700 μl of 30% sucrose cushion in TAE (pH 7.9) (40 mM Tris, 2 mM Na-EDTA; adjusted to pH 7.9 with acetic acid) containing 10 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Calbiochem; nuclease and protease free) per ml and additions as described above, in SW60 tubes, and spun (60,000 rpm, 2.5 h, SW60 Ti rotor, 4°C). The 30% cushions were pooled, syringe filtered to remove particles (0.45 μm pore diameter, low protein binding), divided between two prewashed Centricon 500 filtration units (Amicon), concentrated (6,000 rpm, SS34 rotor, 4°C) until the volume was 100 μl, and washed twice with wash buffer (WB), which was made up of TAE (pH 7.9) containing BSA and the additions described above. A sample was removed for analysis. (SDS was added to 1% and KOAc was added to 1 M, DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform [1:1] and then chloroform and precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 20 μg of glycogen.) Minichromosomes were frozen on dry ice and stored at −20°C. For electroelution from agarose gels, a 60-ml 0.7% agarose gel (6 cm wide, 10 cm long; SeaKem GTG agarose for nucleic acids >1 kb; FMC) in TAE (pH 7.9) with a central 4.4-cm well (1.5 mm wide) flanked by marker wells was cooled to 4°C in a Bio-Rad Mini-Sub Cell with TAE (pH 7.9) as a running buffer. Marker wells were loaded with sample buffer containing xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue. Minichromosomes were adjusted to 10% sucrose (without dyes) and electrophoresed at 40 V for 1.3 h at 4°C with buffer recirculation. A gel slice defined by the midpoints of the two dye bands in the marker lanes was excised and placed in SpectraPor 7 dialysis tubing (flat width of 24 mm, molecular weight cutoff of 8,000), which had been soaked in TAE (pH 7.9), 0.01% NP-40, 10 μg of BSA per ml at 4°C. The same buffer (2.5 ml) was added, and the tubing was secured with dialysis clips. Electroelution was at 40 V, 1.5 h, 4°C with buffer recirculation. The current direction was reversed for 30 s. The eluate was syringe filtered as described above to remove pieces of agarose, protease inhibitors and 2-ME were added, and the eluate was concentrated to about 100 μl in a prewashed Centricon 30 for 40 min as described above. The preparation was washed twice with 1 ml of WB for 30 min, to a final volume of about 100 μl.

Preparation of RNA and Northern blot analysis.

After induction, spheroplasts from 40 ml of culture were collected and resuspended in 400 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–10 mM EDTA–0.5% SDS, mixed with 400 μl of phenol and incubated at 65°C for 30 min with occasional, brief vortexing. The aqueous phase was extracted again with phenol and then chloroform. RNA was precipitated with ethanol after adding 0.3 M NaOAc (pH 5.3), resuspended in 400 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 1% 2-ME, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and stored at −80°C. Equal amounts (0.25 μg) of RNA were mixed with 27 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid), 6.9 mM NaOAc, 1.4 mM EDTA, 25% formaldehyde, 69% formamide, and 0.01% bromophenol blue to 16.7 μl and incubated for 15 min at 65°C. NH4OAc (3.3 μl, 0.5 M) was added. Samples were electrophoresed at 5 V/cm for 12 h in a 1% agarose gel containing 17% formaldehyde, 20 mM MOPS, 5 mM NaOAc, and 1 mM EDTA. The gel was blotted and hybridized overnight at 68°C with the 600-bp BsaBI-PacI CUP1 fragment from pGEM-TAC as a probe.

Topoisomer analysis.

Purified TAC-DNA was loaded in a 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gel (15 by 10 cm) in the presence or absence of chloroquine diphosphate and electrophoresed at 45 V for 4.6 h with buffer recirculation (9). Gels were blotted and probed with a HindIII digest of pGEM-TAC labeled by random priming. Linking number standards were prepared as described previously (9) using pSP72. For analysis of TAC directly from cells, DNA was isolated by rapid extraction of induced and uninduced spheroplasts with 1% SDS and purified as described above.

Monomer extension.

To prepare core particles, 25 to 40 ng of TAC minichromosomes were incubated in 40 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–35 mM NaCl–3 mM CaCl2, with 2 to 4 U of micrococcal nuclease (MNase) (Worthington) for 2 min at 30°C, and EDTA was added to 5 mM. Core particle DNA was extracted, purified from 3% agarose gels, and end labeled with T4 kinase. Core DNA was denatured with alkali, annealed with excess template, and extended with Klenow enzyme, in the presence or absence of a restriction enzyme (61). With pGEM-TAC(+) as template, BamHI, SapI, XcmI, Bsu36I, and DraIII were used. With pGEM-TAC(−), SapI, BamHI, XcmI, BglII, and BstBI were used. Products were analyzed in 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Primer extension.

Analysis was performed as described previously (56). Nuclei were prepared from 500 ml of cells as described above and resuspended in 4 ml of 10 mM HEPES-Na (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.05 mM CaCl2 with protease inhibitors and 2-ME as described above. MNase (Worthington) was added to 650-μl aliquots of nuclei to 0 to 80 U/ml and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. EDTA was added to 10 mM, SDS was added to 1%, and DNA was purified as described above and dissolved in 80 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer containing RNase. For a free DNA control, pCP1A was digested with MNase to various degrees. MNase-digested DNA (5 μl) was mixed with primer (end labeled with T4 kinase and [γ-32P]ATP) at 10 nM with 1.6 U of Vent polymerase in buffer supplied by the manufacturer (NEB). The primers used were CUP1A (5′-CTTCACCACCCTTTATTTCAGGCTG-3′) and CUP1B (5′-CGAAATCTGGGGATTCTATACAGAG-3′). Multiple rounds of extension were performed as follows. DNA was denatured for 5 min at 95°C; followed by 20 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min; followed by 72°C for 5 min. DNA was purified and analyzed in 6% sequencing gels.

Restriction enzyme accessibility.

TAC minichromosomes (4 ng) were mixed with an appropriate plasmid (4 ng) as an internal control (either pGEM-TAC, pBR322, or pGEM-TRP1ARS1) and a BstEII digest of λ DNA at 1 ng/μl in a mixture of 100 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg of BSA per ml, 5 mM 2-ME, and 0.1 mM AEBSF and incubated at 30°C. A zero-time sample (18 μl) was removed, and then 2 to 20 U of restriction enzyme was added. Aliquots were removed at various times and quenched with an equal volume of 2% SDS–20 mM Na-EDTA. DNA was purified as described above. If the restriction site was not unique in TAC, the DNA was digested with HindIII. DNA was resolved in 0.8% agarose gels, and Southern blots were probed either with pGEM-TAC or, if a second digestion had been performed, with the 238-bp HindIII-BglII fragment from pGEM-TAC. Rates of digestion were determined with a phosphorimager.

Transcription run-on analysis.

Electroeluted minichromosomes (15 to 50 ng) were incubated in a mixture of 90 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 M NH4OAc; 0.6 mM (each) ATP, GTP, and CTP; 5 mM MgCl2; 2.5 mM MnCl2; 1 U of RNase Prime Inhibitor (Eppendorf) per μl; and 45 μCi of [α-32P]UTP at 3,000 Ci/mmol in the presence or absence of 20 μg of α-amanitin per ml for 20 min at 30°C. Na-EDTA was added to 10 mM. Free label was removed with a Sephadex G-50 spin column, and purified RNA was denatured for use as a probe of a Southern blot.

RESULTS

Purification of the TRP1 ARS1 CUP1 (TAC) minichromosome.

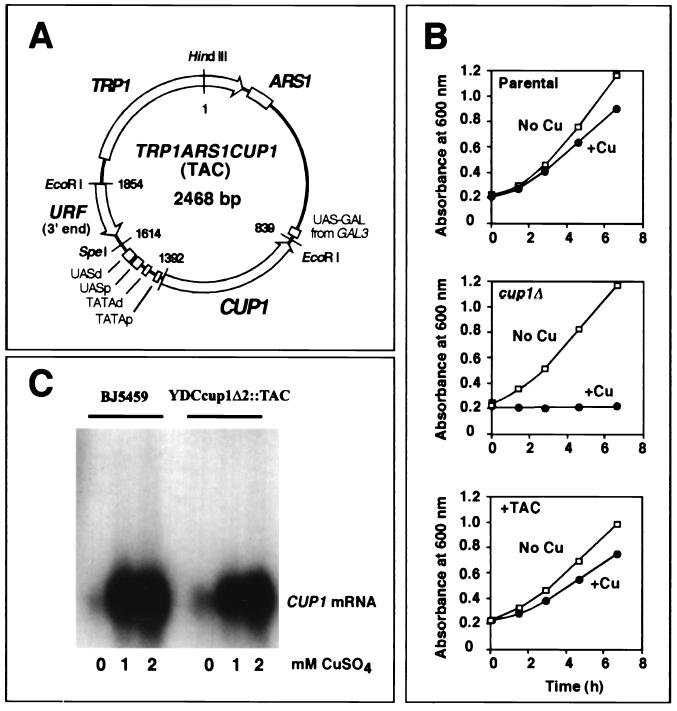

CUP1 is present in multiple copies per haploid genome, and strains with higher copy numbers are more resistant to copper (23). The genes are tandemly reiterated with a 2-kb repeat unit containing CUP1 and another gene of unknown function (URF). The haploid strain BJ5459 was chosen for these studies because it carries protease mutations, which should reduce proteolysis of chromatin during isolation. It is resistant to 1 mM copper and contains about eight copies of CUP1 at a single locus (not shown). These were deleted to obtain a cup1Δ strain, which was then cured of the 2μm circle plasmid (an endogenous yeast plasmid present at high copy number in most laboratory strains) as described previously (3). This strain was transformed with TRP1 ARS1 CUP1 (TAC), a 2,468-bp yeast plasmid based on TRP1 ARS1 (62) (Fig. 1A). To demonstrate that CUP1 in TAC is fully functional, growth was measured in the presence of 1 mM copper (Fig. 1B). The parental strain (BJ5459) grew well in the presence of copper, with a doubling time about 20% longer. The cup1Δ strain grew at the same rate as BJ5459 in the absence of copper, but was inviable in the presence of copper. The introduction of TAC restored growth in 1 mM copper, indicating that CUP1 in TAC is fully functional. The copy number of TAC was measured by Southern blot analysis at an average of 10 per cell (it is likely that asymmetric segregation of ARS plasmids at cell division (45) will result in cells with significantly more or less than 10 copies of TAC). The correlation between the copy number of CUP1 and the degree of resistance to copper (23) suggests that most of the TAC episomes are likely to be active in the presence of 1 mM copper.

FIG. 1.

The TRP1 ARS1 CUP1 (TAC) episome protects yeast cells from the toxic effects of excess copper ions. (A) Map of the TAC episome. TAC is based on TRP1 ARS1, a yeast genomic EcoRI fragment (1,453 bp) capable of autonomous replication. TRP1 encodes an enzyme required for the biosynthesis of tryptophan and is used as a selection marker. ARS1 is the origin of replication. There is a UASGAL from GAL3 within TRP1 ARS1. CUP1 was inserted at the EcoRI site in TRP1 ARS1. The CUP1 promoter contains two UASs: proximal (−106 to −142 [UASp]) and distal (−146 to −220 [UASd]), both of which contain binding sites for Ace1 and HSF. There are two good consensus TATA boxes, at −77 (TATAd) and −33 (TATAp) relative to the transcription start site. The insert also includes the 3′ untranslated region belonging to the URF neighboring CUP1. (B) TAC protects cells from copper toxicity. The growth of yeast cells was monitored by A600. Cells from overnight cultures grown in the absence of copper were inoculated into medium with or without 1 mM copper(II) sulfate to an initial optical density of about 0.2. The parental strain, BJ5459 (doubling times were 160 min without copper and 185 min with copper), and the cup1Δ strain, YDCcup1Δ2 (170 min without copper), were grown in synthetic complete medium. YDCcup1Δ2::TAC was grown in synthetic complete medium lacking tryptophan (185 min without copper and 225 min with copper). (C) Induction of CUP1 in spheroplasts. CUP1 mRNA (about 600 nucleotides) was detected by Northern blot hybridization with a CUP1 probe. Spheroplasts were incubated in SM with copper(II) sulfate added as indicated. RNA was prepared from spheroplasts after 30 min at 30°C with shaking at 225 rpm in an incubator.

A method for the purification of the TAC minichromosome as chromatin was developed. In the first step, cells were resuspended in medium with sorbitol as an osmotic stabilizer and digested with lytic enzyme to obtain spheroplasts, which were then treated with 5 mM copper(II) sulfate to maximize induction of CUP1. The induction of CUP1 under these conditions was followed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1C). CUP1 was strongly induced in both the TAC-containing strain (about sixfold in 2 mM copper) and the parental strain with chromosomal CUP1 (about ninefold). However, this level of induction was significantly less than we were able to measure in intact cells (about 30-fold; not shown), and there was significant expression of CUP1 even in the absence of copper. Why CUP1 is partially induced in spheroplasts is unclear, but it is possible that it is part of a stress response to spheroplasting (1). To obtain a strain containing TAC with inactive CUP1, the gene for its transcriptional activator, Ace1p, was deleted. This strain expressed CUP1 at very low levels (not shown).

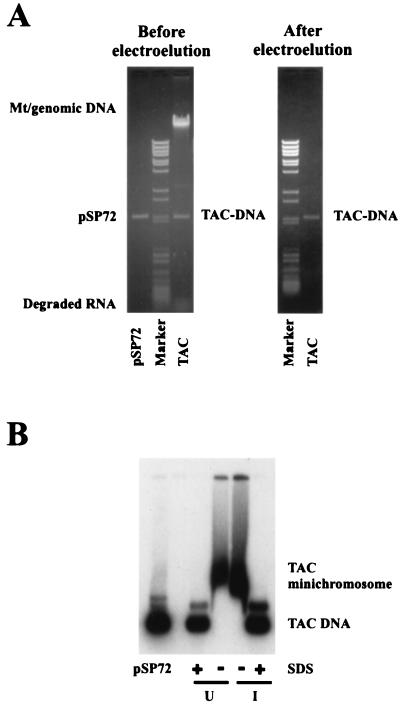

Native TAC chromatin was isolated from copper-induced, uninduced, and ace1Δ cells. Low-ionic-strength buffers were used to prevent nucleosome sliding and to retain proteins. Purity was assessed by analysis of extracted nucleic acids (Fig. 2A): TAC chromatin preparations also contained small amounts of mitochondrial nucleoids, genomic chromatin, and digested ribosomes. TAC DNA was mostly supercoiled, with only a little nicked circle, indicating that TAC chromatin was not damaged by nucleases. This represents a high degree of purity (yields were 40 to 60%, corresponding to about 1 μg of plasmid DNA per liter of cells). This preparation was used for analysis of chromatin structure (see below), but for transcription experiments, TAC was further purified by electroelution from agarose gels (Fig. 2A). Minichromosomes were analyzed in an agarose gel, with or without treatment with SDS to remove the proteins (Fig. 2B). In the absence of SDS, TAC DNA migrated more slowly, as chromatin, with no free TAC DNA present, confirming that the minichromosomes remained substantially intact after purification.

FIG. 2.

Purification of the TRP1 ARS1 CUP1 (TAC) episome. (A) Nucleic acids extracted from a typical preparation of TAC minichromosomes, before and after electroelution, analyzed in a 0.8% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Supercoiled pSP72 (a plasmid of similar size to TAC; 2,472 bp) was used as a marker. Marker, a mixture of λ DNA BstEII and pBR322 MspI digests. (B) Analysis of TAC chromatin in an agarose gel. Electroeluted uninduced (U) and induced (I) TAC minichromosomes were incubated briefly with or without 1% SDS before loading in a 0.8% agarose gel. The gel was blotted and probed with radiolabeled pGEM-TAC.

Topological analysis of TAC minichromosomes in vitro and in vivo.

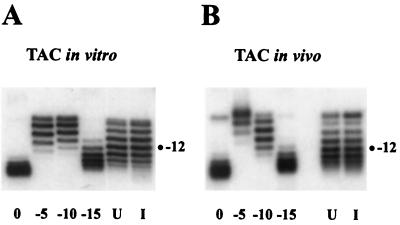

Topological analysis can be used to count nucleosomes on closed circular DNA, using the fact that a nucleosome protects one negative supercoil from relaxation by topoisomerase (49). DNA was extracted from TAC minichromosomes, and topoisomers were resolved in a chloroquine gel (Fig. 3). By comparison with a set of standards of defined linking number, the centers of the linking number distributions were determined (12). The topologies of purified TAC minichromosomal DNA from uninduced and copper-induced cells were very similar, with 12.0 ± 0.2 (n = 2) and 11.8 ± 0.8 (n = 3) negative supercoils, respectively. TAC purified from ace1Δ cells (not shown) contained 11.0 ± 0.9 (n = 3) negative supercoils, about one less than TAC from induced and uninduced cells. However, whether this difference is significant is unclear, because the standard errors overlap. The topologies of TAC purified from uninduced, induced, and ace1Δ cells were compared with those of TAC in vivo by rapid extraction of DNA from spheroplasts: the values were 12.0 ± 0.7 (n = 2), 12.5 ± 0.4 (n = 9), and 12.2 ± 0.6 (n = 3) supercoils, respectively. The values for induced TAC and TAC from ace1Δ cells are slightly higher than those for the purified minichromosomes (although the standard errors overlap). It was also noted that the topoisomer distributions of purified TAC were broader than those of TAC in vivo. An important point here is that the linker DNA in purified TAC chromatin is completely relaxed (it copurifies with topoisomerase activity) (data not shown), but in vivo, TAC minichromosomes might not be completely relaxed, depending on the balance between supercoiling and relaxing activities. In conclusion, topological analysis is consistent with the presence of 10 to 13 nucleosomes in TAC minichromosomes, both in vitro and in vivo. This estimate is sensitive to the possible contributions of RNA polymerase II (Pol II), remodeling complexes, and other factors to DNA supercoiling.

FIG. 3.

Topological analysis of copper-induced and uninduced TAC minichromosomes in vitro and in vivo. (A) Determination of the linking numbers of uninduced and copper-induced TAC minichromosomes in vitro. DNA extracted from preparations of induced (I) and uninduced (U) TAC was electrophoresed in an agarose gel containing 10 μg of chloroquine per ml. Linking number standards with an average of 0 (relaxed), 5, 10, and 15 negative supercoils were prepared by using pSP72. Southern blots probed with pGEM-TAC are shown. (B) Determination of the linking numbers of uninduced and copper-induced TAC minichromosomes in vivo. DNA extracted directly from induced and uninduced spheroplasts was analyzed as in panel A, except that the gel contained 7.5 μg of chloroquine per ml.

RNA Pol II is present on highly purified TAC minichromosomes.

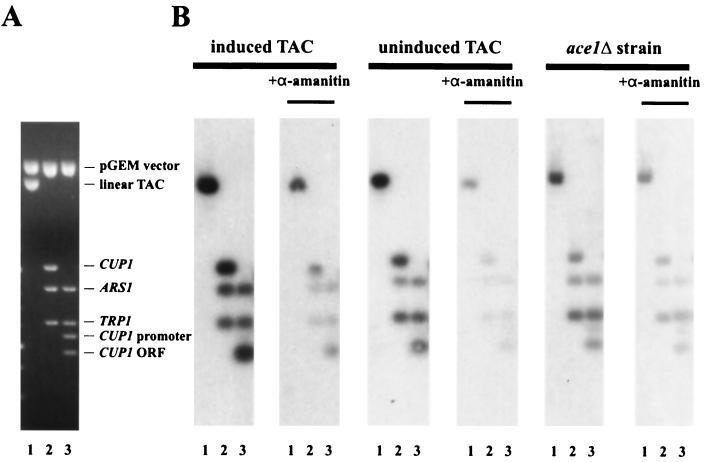

Transcriptionally active chromatin should contain RNA Pol II. Pol II forms stable elongation complexes which stall when nucleotides are removed. Nucleotides (including labeled UTP) were added to electroeluted minichromosomes to allow RNA polymerases to elongate nascent transcripts. To locate the sequences transcribed by Pol II, the labeled RNA was used as probe of a Southern blot of a gel with various restriction digests of pGEM-TAC (Fig. 4A). The digests divided TAC into separate CUP1, TRP1, and ARS1 fragments (lane 2). In lane 3, the CUP1 fragment was cut to give promoter and transcribed (ORF) fragments. The labeled RNA gave a strong signal with the TAC band and did not hybridize at all with the pGEM vector band, indicating that hybridization was specific (Fig. 4B). RNA from copper-induced minichromosomes gave a strong signal with the CUP1 fragment, which was sensitive to α-amanitin (a specific inhibitor of Pol II, at low concentrations), indicating that Pol II is still present on CUP1 after purification. Transcription was not completely inhibited by α-amanitin, probably because this drug inhibits the translocation step in RNA synthesis (58) and would allow the addition of a single nucleotide to the nascent transcript before blocking synthesis; if this nucleotide is UTP, the transcript would be end labeled. The ARS1 fragment contains the 3′ end of TRP1, perhaps accounting for the signal on this fragment, but there might be some readthrough transcription into ARS1 from CUP1. All transcripts hybridizing to CUP1 were derived from the ORF, because the promoter fragment did not hybridize at all. This also shows that Pol II must have terminated transcription before reaching the CUP1 promoter region. TRP1 is transcriptionally active in all TAC preparations and was used to normalize the CUP1 signals: induced TAC synthesized twice as much CUP1 RNA as uninduced TAC and 5 times more than TAC from ace1Δ cells. These differences were less than expected given that CUP1 is induced sixfold in spheroplasts (Fig. 1C), but could be accounted for if there were substantial readthrough from CUP1 into TRP1 in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Presence of RNA Pol II on CUP1 in purified TAC minichromosomes. Electroeluted TAC minichromosomes were incubated with nucleoside triphosphates (including radiolabeled UTP) for synthesis of run-on transcripts in the presence or absence of α-amanitin. (A) Typical gel used for Southern blots (stained with ethidium). pGEM-TAC was digested with HindIII only (lane 1); HindIII and EcoRI (lane 2); or HindIII, EcoRI, and PacI (lane 3). (B) Hybridization with RNA synthesized in the presence or absence of α-amanitin by electroeluted TAC minichromosomes isolated from induced, uninduced, or ace1Δ cells.

In conclusion, TAC minichromosomes can be isolated substantially intact from yeast cells, and retain amounts of RNA Pol II that correlate with the transcriptional activity of CUP1 in vivo.

The induced CUP1 promoter is more accessible to restriction enzymes.

Restriction enzymes were used to probe the accessibility of CUP1 promoter DNA in copper-induced and uninduced TAC minichromosomes. Restriction enzymes cleave nucleosomal DNA at a very slow rate relative to naked DNA. In these experiments, minichromosomes were mixed with a plasmid as internal control and the kinetics of digestion of TAC chromatin and plasmid DNA were compared. This approach gives a quantitative estimate of the degree of protection of a particular restriction site (Fig. 5). This protection is likely to be predominantly due to nucleosomes, but other bound complexes might also contribute.

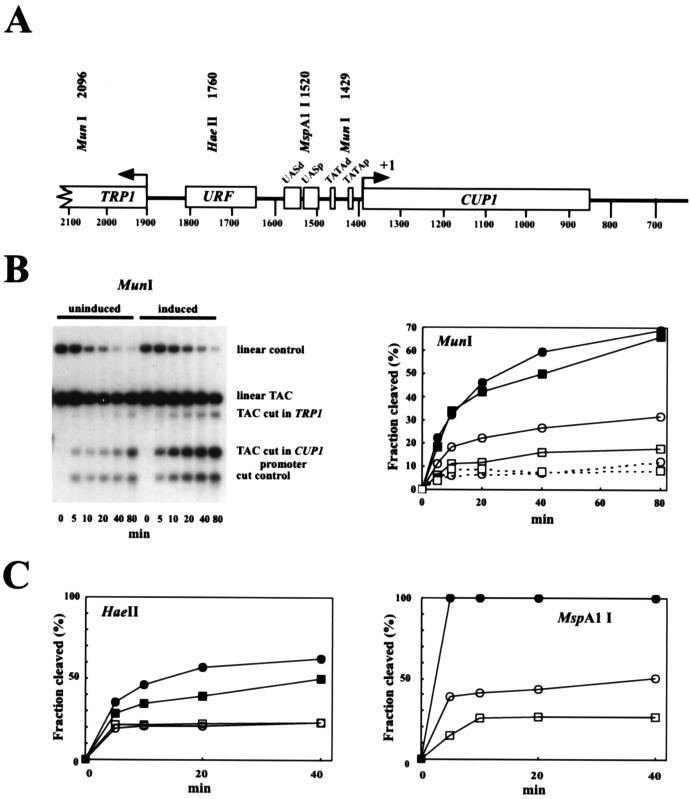

FIG. 5.

Accessibility of restriction sites in the CUP1 promoter in uninduced and induced TAC minichromosomes. (A) Map of relevant restriction sites in TAC. (B) Accessibility of the MunI site in the CUP1 promoter. TAC chromatin (not electroeluted) was mixed with plasmid DNA as an internal control and digested with MunI for the times indicated. DNA was purified and digested with HindIII to linearize both TAC and the control plasmid (pGEM-TAC). A Southern blot was probed with the HindIII-BglII fragment from TAC (the BglII site is at 238). Data were quantitated by phosphorimager analysis and plotted for the uninduced control (■), uninduced TAC (□), induced control (●), and induced TAC (○). The dashed lines show the plots for the other MunI site, in TRP1. (C) Accessibility of the HaeII and MspA1I sites. Plots of data from phosphorimager analysis. These sites are both unique in TAC. Symbols are as in panel B.

There is a MunI site between the putative TATA boxes in the CUP1 promoter. MunI cleaved about 15% of uninduced TAC, reaching a plateau, indicating that 85% of the promoters are inaccessible (Fig. 5B). In contrast, about 35% of induced TAC was accessible. The other MunI site in TAC is located just inside the transcribed region of TRP1 and is strongly and equally protected in uninduced and induced TAC (about 10% cleavage). Similarly, the MspA1I site in the proximal UAS was accessible in 25% of uninduced TAC, whereas about 50% of induced TAC was accessible (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the HaeII site in the 3′ URF region was 20% accessible in both induced and uninduced TAC, indicating that induction had no effect on its accessibility. In summary, induced TAC episomes contained more accessible CUP1 promoters than uninduced TAC, indicating that activation of CUP1 coincides with increased exposure of the promoter, presumably to facilitate formation of the transcription complex.

Chromatin structure of the TAC minichromosome.

The chromatin structures of TAC from induced and uninduced cells were examined initially by the indirect end-labeling method (54) to determine whether CUP1 is present in a highly ordered chromatin structure. However, a cleavage pattern consistent with a more complex chromatin structure was observed (not shown), and nucleosome positions could not be determined. Therefore, the monomer extension method (61) for identifying nucleosome positions was used, which was developed to resolve arrays of overlapping positions in complex reconstituted chromatin structures, without ambiguity (10, 11). This method requires purified chromatin; it is unlikely to be effective with nuclei because of the large excess of nucleosomes from the rest of the genome.

Isolated minichromosomes were completely digested to nucleosome core particles by using MNase. DNA was extracted, and core particle DNA (140 to 160 bp) was purified from a gel and end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. Labeled core DNA was then used as primer for extension by Klenow fragment with single-stranded pGEM-TAC DNA as template. The replicated DNA was digested with different restriction enzymes to resolve different regions of the TAC minichromosome. The lengths of the resulting DNA fragments were determined accurately in sequencing gels: each band defines the distance from the border of a nucleosome to the chosen restriction site. A control for sequence-dependent termination by Klenow enzyme involves omission of the restriction enzyme. The borders of each nucleosome were located precisely, with one using the positive strand as template and the other using the negative strand. The data from one template strand define all of the “upstream” nucleosome borders unambiguously and are sufficient to define the chromatin structure. The other strand should give the same nucleosome positions, this time defined by the “downstream” borders. The degree to which the two sets of positioning data are consistent can be assessed by calculating the average distance between the nucleosome borders, which should be close to 147 bp, the size of the core particle.

Because the monomer extension technique is not yet widely used, it is worthwhile discussing some technical points. A slight underdigestion of chromatin by MNase results in core particles that are not completely trimmed to 147 bp. Consequently, bands within about 20 bp of one another are likely to represent different degrees of trimming of the same positioned nucleosome. In the analysis, clusters of bands within 20 bp were counted as the same nucleosome. If core particles are overdigested by MNase, nicks begin to appear. Labeled core DNA was routinely checked in denaturing gels: the size range was typically 140 to 160 bp, with very little nicking. In any case, nicking would not affect the result, because kinase does not label nicks, and end-labeled nicked DNA strands liberated on denaturation of core DNA would give the correct result on extension. Proteins other than nucleosomes which might be bound to the minichromosome will not interfere with nucleosome mapping unless they protect 140 to 160 bp of DNA against extensive digestion by MNase (because the DNA is subsequently gel purified). The contributions of such proteins would appear as nucleosome-free gaps in the map (see below), but this might not be obvious unless there is close to 100% occupancy of their sites.

Initially, TAC episomes from copper-induced and uninduced cells were compared. A complex but highly reproducible band pattern was obtained with no qualitative differences between the induced and uninduced minichromosomes. Some data for induced TAC are shown in Fig. 6A (ind. lanes), and a summary of many data sets using different restriction enzymes to map different parts of TAC is shown in Fig. 6B. The pattern defined 48 different nucleosome positions on TAC (Table 1). The intensities of the bands indicate that some nucleosomes occur more frequently than others. Many of these positions are overlapping and therefore mutually exclusive. The first impression is that nucleosomes are positioned randomly in TAC, but this is not the case. A truly random distribution would yield 2,468 different positions and bands of equal intensity corresponding to every nucleotide position in the sequencing gel. Instead, 48 relatively strong positions were observed. It is emphasized that this complex pattern of nucleosome positions was highly reproducible; data were obtained from many independent preparations (Table 1). The standard errors were relatively small and reflect a combination of some measurements from the less accurate region at the top of each gel and small differences in the degree of trimming of core DNA by MNase. The average distance between nucleosome borders was 151 ± 8 bp, very close to the 147 bp expected, indicating that the data from the positive and negative strands are in agreement: they both describe the same chromatin structure.

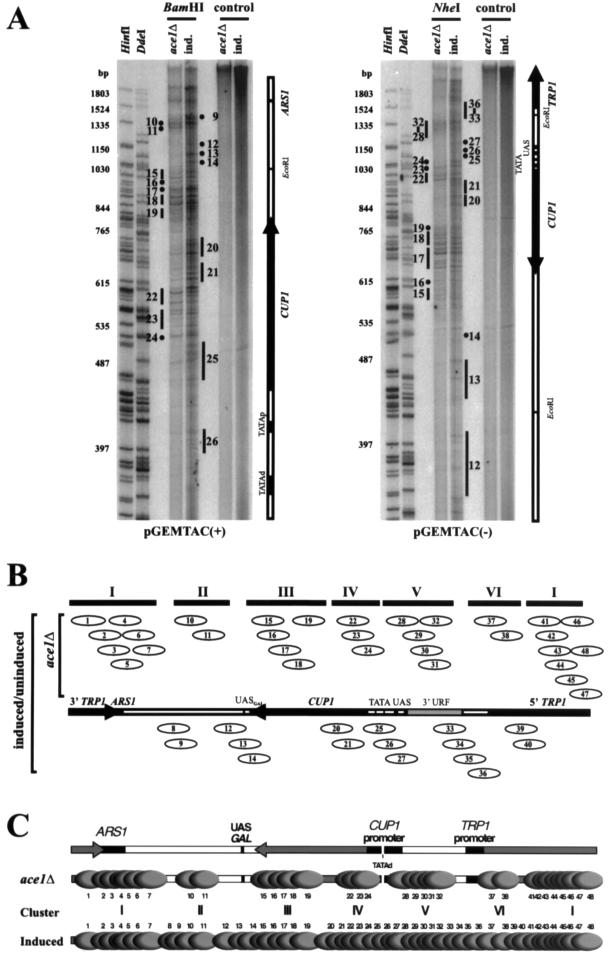

FIG. 6.

Chromatin structure of purified TAC minichromosomes by monomer extension analysis. (A) Typical monomer extension analysis of positioned nucleosomes in TAC from copper-induced (ind.) and ace1Δ cells purified to the stage prior to electroelution. In the examples shown, translational positions were mapped from the BamHI site (at 1833) on the positive strand of pGEM-TAC and the NheI site (at 423) on the negative strand. Controls had extension but no digestion with restriction enzyme. Nucleosome positions are indicated by numbered dots or bars (the latter indicating bands which were included within that nucleosome position, as discussed in the text). They are numbered from 1 to 48 (Table 1), beginning at the HindIII site in TRP1 (Fig. 1A). The markers are HinfI and DdeI digests of λ DNA labeled with T4 kinase; the sizes of some of the bands are indicated to the left. (B) Summary of nucleosome positions in TAC minichromosomes. Nucleosome positions are numbered in the order of their coordinates in TAC relative to the HindIII site in TRP1 (=1). The EcoRI sites mark the boundaries of the CUP1 insert. Positions observed in TAC from ace1Δ cells are shown above the map of TAC, and nonoverlapping position clusters I to VI are indicated. Cluster I includes positions 41 to 48 and 1 to 7. In TAC from uninduced and induced cells, all of the nucleosome positions shown were observed; the novel positions occupying linkers between the clusters are shown below the map of TAC. (C) Distribution of nucleosome positions in TAC. Gray ovals indicate positioned nucleosomes drawn to scale (numbered according to Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Nucleosome positions on TAC minichromosomesa

| Nucleosome | Position

|

Distance (bp) | ace1Δb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + Border | − Border | |||

| 1 | 14 (9) | 164 (12) | 150 | + |

| 2 | 94 (19) | 237 (13) | 143 | + |

| 3 | 131 (1) | 277 (8) | 146 | + |

| 4 | 178 (11) | 321 (8) | 143 | + |

| 5 | 197 (6) | 352 (8) | 155 | + |

| 6 | 244 (7) | 390 (15) | 146 | + |

| 7 | 292 (18) | 453 (26) | 161 | + |

| 8 | 410 (7) | 545 (3) | 135 | − |

| 9 | 441 (10) | 591 (12) | 150 | − |

| 10 | 487 (12) | 642 (15) | 155 | + |

| 11 | 553 (20) | 695 (19) | 142 | + |

| 12 | 666 (12) | 818 (10) | 152 | − |

| 13 | 739 (22) | 889 (13) | 150 | − |

| 14 | 782 (14) | 924 (17) | 142 | − |

| 15 | 840 (11) | 995 (10) | 155 | + |

| 16 | 872 (9) | 1028 (8) | 156 | + |

| 17 | 923 (14) | 1073 (8) | 150 | + |

| 18 | 964 (14) | 1120 (18) | 156 | + |

| 19 | 1028 (15) | 1188 (13) | 160 | + |

| 20 | 1143 (14) | 1291 (20) | 148 | − |

| 21 | 1196 (17) | 1347 (15) | 151 | − |

| 22 | 1238 (7) | 1394 (5) | 156 | + |

| 23 | 1269 (10) | 1429 (9) | 160 | + |

| 24 | 1311 (13) | 1464 (15) | 153 | + |

| 25 | 1367 (14) | 1516 (4) | 149 | − |

| 26 | 1413 (13) | 1552 (8) | 139 | − |

| 27 | 1454 (5) | 1595 (6) | 141 | − |

| 28 | 1479 (10) | 1651 (9) | 172 | + |

| 29 | 1550 (5) | 1690 (17) | 140 | + |

| 30 | 1586 (10) | 1735 (10) | 149 | + |

| 31 | 1624 (6) | 1770 (9) | 146 | + |

| 32 | 1651 (14) | 1810 (12) | 159 | + |

| 33 | 1695 (10) | 1866 (10) | 171 | − |

| 34 | 1748 (16) | 1893 (11) | 145 | − |

| 35 | 1789 (6) | 1939 (15) | 150 | − |

| 36 | 1842 (18) | 2005 (6) | 163 | − |

| 37 | 1903 (17) | 2052 (12) | 149 | + |

| 38 | 1973 (22) | 2106 (12) | 133 | + |

| 39 | 2035 (2) | 2179 (14) | 144 | − |

| 40 | 2071 (10) | 2227 (14) | 156 | − |

| 41 | 2123 (15) | 2268 (13) | 145 | + |

| 42 | 2163 (2) | 2311 (9) | 148 | + |

| 43 | 2185 (7) | 2346 (9) | 161 | + |

| 44 | 2221 (9) | 2373 (6) | 152 | + |

| 45 | 2247 (11) | 2411 (10) | 164 | + |

| 46 | 2270 (1) | + | ||

| 47 | 2300 (1) | + | ||

| 48 | 2350c | + | ||

All band sizes were measured and converted to TAC coordinates, with +1 at the HindIII site, reading clockwise (see Fig. 1A). Data from five separate induced or uninduced minichromosome preparations are included, with analysis using several different restriction enzymes. The standard error is in parentheses and represents the error computed on the average coordinate for each set of bands attributed to a particular positioned nucleosome (due to different degrees of trimming) for the five preparations. The average core particle size is 151 ± 8 bp.

ace1Δ in TAC from ace1Δ cells: +, position occupied; −, position unoccupied.

This nucleosome border was measured only once, for the positive strand only.

Thus, induced and uninduced TAC minichromosomes have qualitatively very similar complex chromatin structures, perhaps representing all possible combinations of the 48 positions observed. They might differ quantitatively in their nucleosome distributions, but it is difficult to compare different monomer extension samples quantitatively, because a control band for normalization is not available. However, the increased accessibility of the restriction sites for MunI and MspA1I in the CUP1 promoter observed on induction (Fig. 5) suggests that nucleosome positions over the promoter are less likely to be occupied after induction. There are multiple ways of arranging the nucleosomes in TAC with respect to one another. Most arrangements give a maximum of 12 or 13 nucleosomes in TAC, consistent with topological measurements in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 3). Thus, TAC chromatin is highly heterogeneous; each minichromosome is likely to have a slightly different chromatin structure from the next.

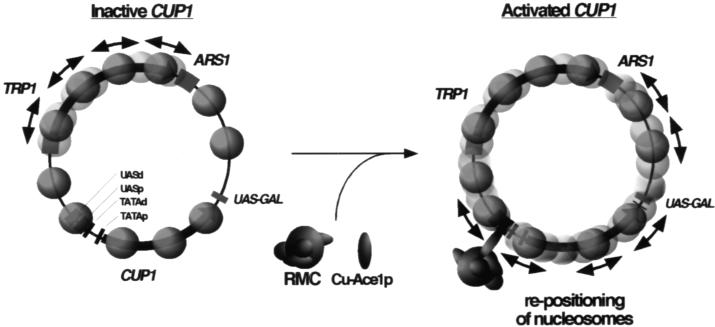

Ace1p-dependent nucleosome repositioning on CUP1 and flanking regions.

To determine the contribution of Ace1p to chromatin structure, TAC isolated from ace1Δ cells was analyzed (Fig. 6A). A simpler chromatin structure was observed in which only 32 of the 48 positions in induced TAC were prominent, i.e., a subset of the same positions (Table 1); the other 16 positions were rarely occupied. The nucleosomes observed can be divided into six clusters of overlapping positions (I to VI in Fig. 4B) separated by linkers of various lengths, some of which contain factor binding sites that could act as nucleosome phasing signals: the 18-bp linker between clusters IV and V contains the distal TATA box in the CUP1 promoter; the very long (151 bp) linker between clusters II and III contains the UASGAL, and the 80-bp linker between clusters V and VI includes the region just upstream of the putative TATA box for TRP1, which might contain an activator binding site. The 41-bp linker between clusters I and II might contain a binding site for an unknown factor, since the function of the DNA between ARS1 and GAL3 remains to be elucidated. However, the 48-bp linker between clusters III and IV and the 22-bp linker between clusters VI and I are within the CUP1 and TRP1 ORFs, respectively, and so are unlikely to represent phasing signals. Nucleosome arrangements indicate a maximum of 11 nucleosomes in TAC from ace1Δ cells (1 or 2 less than TAC from Ace1p-containing cells).

As discussed above, in the presence of Ace1p, more nucleosome positions were observed (Fig. 6; compare ace1Δ and induced lanes), including positions 25, 26, and 27 over the CUP1 promoter and 20 and 21 in the CUP1 ORF. Nucleosome repositioning also occurred over the sequences flanking CUP1, with positions 8, 9, 12, 13, and 14 downstream of the CUP1 insert and positions 33 to 36 and 39 to 40 in the region upstream of CUP1 appearing. These results are summarized in Fig. 6C, in which the nucleosome position clusters observed in ace1Δ cells are shown together with all of the 48 possible positions observed in Ace1p-containing cells. From these observations, it may be concluded that the binding of Ace1p coincides with the repositioning of nucleosomes on CUP1 and its flanking regions from the clusters to the linkers.

TAC also has a complex chromatin structure in nuclei.

A concern in all determinations of nucleosome positions is the possibility of nucleosome sliding. This seems unlikely to be occurring here; sliding requires elevated salt concentrations and temperature (>0.15 M at 37°C in the absence of histone H1) (50), which were avoided throughout purification. Furthermore, sliding would have had to occur to the same precise positions in all preparations. Although sliding seemed unlikely, we addressed the possibility that a single array of precisely positioned nucleosomes was present on CUP1 in nuclei which was disrupted during the subsequent purification step, by analyzing the chromatin structure of TAC minichromosomes in nuclei. The monomer extension method is unlikely to be effective in nuclei, because there would be a very high background from contaminating core particles. Therefore, to examine the chromatin structure of TAC in nuclei, we used primer extension to map MNase-cut sites (56) with primers corresponding to both ends of the CUP1 insert. Nuclei were prepared from uninduced and induced cells containing TAC and digested with increasing amounts of MNase. A typical nucleosomal ladder with a repeat length of about 160 bp was observed (Fig. 7A), as expected for yeast (55). Primer extension analysis of these samples (Fig. 7B) revealed a series of bands unique to chromatin, reflecting cleavage in the linkers, but they are not spaced by 147 bp. The pattern of protected regions of much less than 147 bp was consistent with the complex pattern of overlapping nucleosome positions revealed by monomer extension, and there was no evidence for a single array of positioned nucleosomes. There is almost no difference between induced and uninduced CUP1, although there are some subtle changes in the band pattern and degree of protection in the promoter region. We obtained similar maps for chromosomal CUP1 in nuclei from BJ5459 cells (not shown). Thus, the primer extension map is consistent with the presence of multiple, overlapping positioned nucleosomes in TAC chromatin in nuclei. Furthermore, the fact that TAC minichromosomes from ace1Δ cells isolated in parallel gave a different chromatin structure also suggests that the isolation protocol preserves chromatin structure.

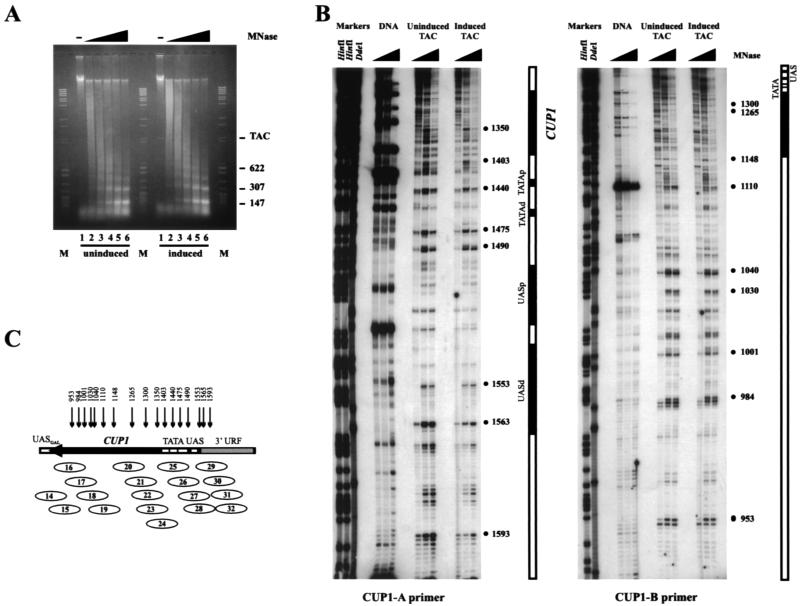

FIG. 7.

Chromatin structure of CUP1 in TAC minichromosomes in nuclei by primer extension analysis. (A) Analysis of DNA from nuclei from copper-induced and uninduced YDCcup1Δ2::TAC digested with MNase in a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Markers were a mixture of λ DNA digested with BstEII and pBR322 digested with MspI (some bands are labeled). (TAC is faintly visible in the undigested control lanes and is mostly nicked under the conditions used for incubation of the nuclei.) The band at the bottom in all lanes is residual RNA. (B) Primer extension mapping of copper-induced and uninduced CUP1 in TAC minichromosomes in nuclei. Samples shown in panel A, lanes 1, 4, and 6, were used. DNA, pCP1A digested with MNase. Major bands are indicated with dots and coordinates in TAC. Markers (DdeI and HinfI) are as in Fig. 6A. (C) Comparison of primer extension data for TAC in nuclei with the nucleosome map obtained for purified TAC by monomer extension (Fig. 6). The arrows indicate the major MNase-cut sites mapped by primer extension; these sites can be fit to linkers between positioned nucleosomes mapped by monomer extension.

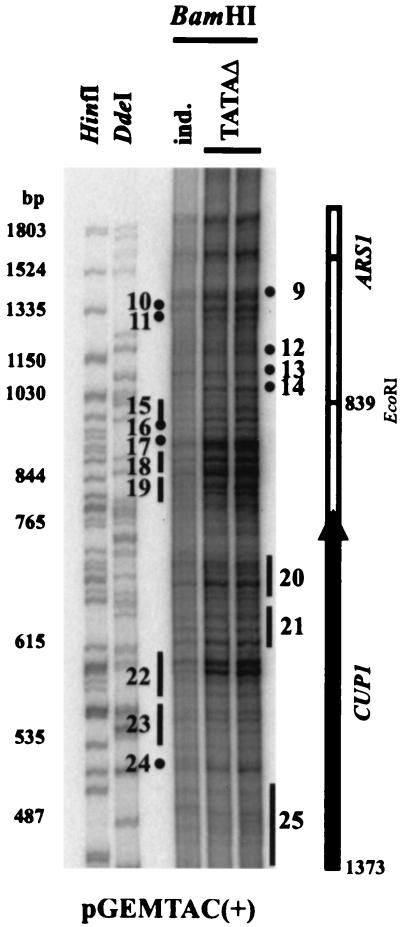

Nucleosome repositioning on CUP1 is independent of transcription.

Ace1p-dependent nucleosome repositioning might be due to transcription by RNA Pol II or to a chromatin remodeling complex recruited by Ace1p. The former seemed unlikely, because nucleosomes were repositioned in untranscribed regions as well as transcribed regions. To distinguish between the two, a yeast strain containing TAC with both TATA boxes in the CUP1 promoter mutated to prevent transcript initiation was used (confirmed by mung bean nuclease mapping of transcripts) (data not shown). Nucleosome positions in these TAC minichromosomes were identical to those in the induced state, indicating that nucleosomes were repositioned in the presence of Ace1p, but in the absence of transcription (Fig. 8). Taken together, our observations constitute strong evidence for the recruitment by Ace1p of a nucleosome repositioning activity which acts over the entire CUP1 gene and some flanking sequences.

FIG. 8.

Chromatin structure of TAC minichromosomes containing TATA box mutations in the CUP1 promoter. Monomer extension analysis to compare nucleosome positions in copper-induced and TATA-mutant TAC minichromosomes. Two independently prepared TATA mutant samples are shown. Labeling is as in the legend to Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

CUP1 was chosen as a model for understanding gene activation in the context of chromatin structure, because its regulation is relatively simple and it has a strongly inducible promoter. An effective method for the purification of episomes was developed, and evidence that their chromatin structures remained substantially intact has been presented, including the retention of RNA Pol II in amounts correlating with transcriptional activity in vivo. The chromatin structures of purified TAC minichromosomes in various states of transcriptional activity were determined by the monomer extension method. A relatively ordered chromatin structure is observed in the absence of the transcriptional activator, Ace1p. In its presence, the clusters of nucleosome positions were disrupted, because nucleosomes were repositioned over linkers. Nucleosome repositioning requires Ace1p, but is independent of transcription, because it occurred even when the TATA boxes in the CUP1 promoter were mutated.

Translationally positioned nucleosomes in TAC.

TAC minichromosomes isolated from cells containing Ace1p are heterogeneous in chromatin structure: 48 differently positioned nucleosomes were identified. Overlapping nucleosome positions were observed over the entire plasmid. These can be occupied in many different combinations to give totals of 11 to 13 nucleosomes, in agreement with the topological analysis. The complexity of the chromatin structure of induced TAC minichromosomes is about what would be expected from in vitro reconstitution experiments. For example, on two 358-bp fragments containing a 5S RNA gene, 6 or 12 positions were observed (41) indicating “position densities” of about 1 per 30 or 60 bp, respectively, and for a 359-bp fragment containing the Drosophila hsp70 promoter, 5 positions were observed (1 per 72 bp) (19). For TAC (2,468 bp), the value is 1 per 51 bp. In fact, the translational positions mapped in native induced TAC chromatin are the same as those formed by reconstitution of nucleosomes from purified components (C.-H. Shen and D. J. Clark, unpublished data). Therefore, DNA sequence determines the possible positions in TAC, but events on the plasmid determine which positions are occupied and when.

Chromatin structure of the TAC minichromosome.

In the absence of Ace1p, the chromatin structure of CUP1 and its flanking sequences is relatively ordered, with clusters of alternative overlapping nucleosome positions separated by linkers that are rarely occupied by nucleosomes. This may represent a relatively undisturbed chromatin structure laid down during nucleosome assembly coupled to DNA replication, which might be determined in part by factors acting as nucleosome phasing signals (15) bound at the TRP1 and CUP1 promoters, at ARS1 (the origin recognition complex), at the UASGAL and perhaps at other sites in TAC. All of these sites except ARS1 are at least partly in the linker in ace1Δ cells. In the case of ARS1, a MNase-hypersensitive site was observed by indirect end labeling (not shown), previously reported by others (54), indicating that ARS1 is accessible in a significant fraction of TAC minichromosomes (presumably those with arrays including nucleosomes 1 and 4 or 6 or 7, placing ARS1 in the linker). In TAC from cells containing Ace1p, the presence of nucleosomes on a fraction of each of these binding sites implies that remodeling might lead to some displacement of these factors.

TRP1 was used as a selection marker for TAC and was therefore in its transcriptionally active state under all conditions examined. The activity of TRP1 was insufficient to disturb the chromatin structure of CUP1 in ace1Δ cells, although it might have had minor effects. The TRP1 promoter in TRP1 ARS1 is truncated and might be missing important regulatory elements which reduce its ability to recruit remodeling complexes as well as its transcriptional activity. Remodeling of CUP1 does have effects on TRP1: in the presence of Ace1p, nucleosomes occupy positions 39 and 40 at the 5′ end of TRP1 and positions 8, 9, and 12 to 14 near ARS1. The chromatin structure of the TRP1 ARS1 minichromosome has been studied in detail by using indirect end labeling (54): three strongly positioned nucleosomes were identified next to ARS1. However, insertion of DNA at the EcoRI site disrupted the positioning of these nucleosomes (44). This is also where CUP1 was inserted and probably accounts for the less ordered structure of the ARS1 region in TAC. Another relevant factor is the much higher copy number of TRP1 ARS1 (100 to 200 per cell) (62) relative to TAC and other TRP1 ARS1 plasmids with inserts (20, 53): most TRP1 genes in TRP1 ARS1-containing cells might be inactive and unremodeled, with more ordered structures.

How does Ace1p target the remodeling complex to CUP1?

In the absence of Ace1p, the chromatin structure of the CUP1 promoter is such that the distal TATA box is placed in the linker between two clusters of overlapping positions, but the UASs (coordinates 1510 to 1612) may be completely open (positions 30 to 32), partly covered (position 29), or completely contained within a nucleosome (position 28). For induction, Ace1p must bind to its site in order to target the remodeling complex. It is not known whether Ace1p, like the thyroid hormone receptor (59), can recognize its binding site in a nucleosome, or whether, like many transcriptional activators (2), it has greatly reduced affinity for its site when in a nucleosome. If the latter is the case, the presence of multiple binding sites for Ace1p (two in each UAS) offers a potential solution: for positions 29 to 32, at least one site is present in the linker and available for Ace1p to bind. In the case of position 28, in which all the sites are covered, the weakened binding of several Ace1p molecules might be sufficient to disrupt the nucleosome (2). In this model, Ace1p should be able to access at least one binding site independently of which nucleosome positions 28 to 32 happen to be occupied. An alternative, “concerted probing,” model postulates the formation of a complex between copper-activated Ace1p and the remodeler, which then “probes” each nucleosome in turn until Ace1p recognizes its binding site.

It is instructive to compare CUP1 with PHO5, for which the relationship between chromatin structure and gene expression in yeast has been most thoroughly studied (reviewed in reference 52). Induction of PHO5 correlates with the disruption of an ordered array of four positioned nucleosomes on the PHO5 promoter and requires the presence of a binding site for the Pho4p activator in the linker between the central pair of nucleosomes. CUP1 has a much less ordered chromatin structure at the promoter, but there are four binding sites for Ace1p, which, as discussed above, could facilitate binding of Ace1p. The large increase in accessibility to nucleases at the PHO5 promoter indicates that nucleosome disruption is likely to involve dramatic conformational changes or displacement of the four nucleosomes rather than just repositioning. For CUP1, relatively modest increases in accessibility to restriction enzymes were observed on induction (not shown). As for CUP1, chromatin remodeling at PHO5 is dependent on the presence of activator, but transcription is not required. Whether remodeling of PHO5 chromatin is confined to the promoter or whether, like CUP1, it involves the rest of the gene and flanking sequences is unclear.

Mechanism of remodeling of CUP1 and its flanking sequences.

It is not known which of the chromatin remodeling activities identified in yeast is involved in CUP1 regulation. Nucleosome repositioning could be the direct result of recruitment by Ace1p of the SWI-SNF complex, RSC (8), or one of the I-SWI-like complexes. Alternatively, it might be the indirect consequence of a targeted histone modification, such as acetylation. Experiments addressing these possibilities are in progress. Current models for the mechanism of chromatin remodeling have been reviewed recently (22, 24, 38, 43). In the “activator model” (43), gene-specific activators recruit a remodeling complex directly to the promoter, which then alters local chromatin structure to facilitate transcription (39, 40). In vitro, remodeling complexes catalyze nucleosome sliding (19, 26, 57) and/or nucleosome transfer (35). Remodeled nucleosomes also have an altered conformation and can form dimer-like particles (4, 34, 47).

Much of the evidence for the mechanism of remodeling is based on biochemical data in vitro. We have provided direct support for the activator model in vivo by isolating and examining the structures of native chromatin: we have shown that remodeling of CUP1 is dependent on its transcriptional activator, Ace1p, that remodeling involves the repositioning of nucleosomes, and that, perhaps surprisingly, remodeling is not confined to the CUP1 promoter, but includes the entire gene and unrelated flanking regions also. While there is much evidence that gene activation is correlated with disruption of a relatively ordered chromatin structure, the structural nature of this disruption has not been elucidated. Our observations suggest that a major part of this structural transition is the dynamic redistribution of nucleosomes. Repositioned nucleosomes protected 147 bp of DNA from digestion by MNase, and so, by this criterion, are not conformationally altered. However, remodeled nucleosomes might be relatively short-lived intermediates in vivo. Furthermore, remodeled nucleosomes might not protect 147 bp of DNA from MNase digestion (they might be relatively unstable or, if a dimer-like particle is formed, they might protect a larger piece of DNA which would not be present in core DNA preparations).

The remodeling activity recruited to CUP1 by Ace1p is apparently capable of reorganizing a domain of chromatin structure defined by the limits of nucleosome repositioning observed. This extends from positions 8 and 9 near ARS1 to positions 39 and 40 at the 5′ end of TRP1. These are outside the CUP1 insert and indicate that the remodeling activity influences nucleosome positions over nearly 2 kb of DNA and perhaps over the entire TAC plasmid. The fact that remodeling is not confined to the promoter suggests that the remodeling complex recruited by Ace1p somehow reorganizes a domain of chromatin structure rather than working only on promoter nucleosomes. How it might achieve this is a matter for speculation, but the looping and tracking models suggested for enhancer action (5) are obvious candidates. Remodeling activity might create a “fluid” chromatin structure (24). Thus, the heterogeneity observed in TAC minichromosomes is likely to reflect a highly dynamic chromatin structure, in which facile nucleosome movement between observed translational positions is catalyzed by the remodeling complex recruited by Ace1p (Fig. 9). The fact that these positions overlap might be important in the mechanism of nucleosome transfer. Facile nucleosome movement should facilitate events such as the formation of a transcription complex at the CUP1 promoter and the passage of RNA Pol II.

FIG. 9.

A fluid chromatin model for the remodeling of the CUP1 gene in TAC. A chromatin structure representative of TAC minichromosomes containing inactive CUP1 (ace1Δ) is shown. TRP1 is transcriptionally active and is shown as undergoing remodeling (double-headed arrows indicate nucleosome repositioning). The first step in activation of CUP1 for transcription is the binding of copper-activated Ace1p to one of its binding sites in the UASs. How Cu-Ace1p might gain access to its sites is discussed in the text. Cu-Ace1p recruits a remodeling complex (RMC) to the CUP1 promoter, which catalyzes nucleosome repositioning on CUP1 and its flanking sequences. The continual free movement of nucleosomes between positions results in a fluid chromatin structure, rendering the underlying DNA transparent and facilitating the formation of a transcription complex at the CUP1 promoter and the passage of RNA Pol II (see text for a discussion of possible mechanisms).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ramin Akhavan for the ace1Δ strain; Carolyn Neal for the mutant strain; Yossi Shiloach and Loc Trinh for fermenter-grown cells; and A. Dean, D. Hu, J. Thorner, and the American Type Culture Collection for plasmids. We thank Chris Szent-Györgyi for useful discussions; Ann Dean, Jurrien Dean, Rohinton Kamakaka, Alan Kimmel, and Alan Wolffe for comments on the manuscript; and Anne Dranginis for communicating unpublished results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams C C, Gross D S. The yeast heat shock response is induced by conversion of cells to spheroplasts and by potent transcriptional inhibitors. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7429–7435. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7429-7435.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams C C, Workman J L. Nucleosome displacement in transcription. Cell. 1993;72:305–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfieri J A, Clark D J. Isolation of minichromosomes from yeast cells. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazett-Jones D P, Côté J, Landel C C, Peterson C L, Workman J L. The SWI/SNF complex creates loop domains in DNA and polynucleosome arrays and can disrupt DNA-histone contacts within these domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1470–1478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwood E M, Kadonaga J T. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science. 1998;281:60–63. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchman C, Skroch P, Welch J, Fogel S, Karin M. The CUP2 gene product, regulator of yeast metallothionein expression, is a copper-activated DNA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4091–4095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt T R, Sternberg E J, Gorman J A, Clark P, Hamer D, Rosenberg M, Crooke S T. Copper metallothionein of yeast, structure of the gene, and regulation of expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3332–3336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairns B R, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg R D. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark D J. Counting nucleosome cores on circular DNA using topoisomerase I. In: Gould H, editor. Chromatin: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey C, Pennings S, Allan J. CpG methylation remodels chromatin structure in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:276–288. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey C, Pennings S, Meerseman G, Wess T J, Allan J. Periodicity of strong nucleosome positioning sites around the chicken adult β-globin gene may encode regularly spaced chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11210–11214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depew R E, Wang J C. Conformational fluctuations of DNA helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4275–4279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducker C E, Simpson R T. The organized chromatin domain of the repressed yeast a cell-specific gene STE6 contains two molecules of the corepressor Tup1p per nucleosome. EMBO J. 2000;19:400–409. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eadara J K, Lutter L C. RNA polymerase locations in the simian virus 40 transcription complex. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22020–22027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedor M J, Lue N F, Kornberg R D. Statistical positioning of nucleosomes by specific protein-binding to an upstream activating sequence in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:109–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fürst P, Hu S, Hackett R, Hamer D. Copper activates metallothionein gene transcription by altering the conformation of a specific DNA binding protein. Cell. 1988;55:705–717. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamer D H, Thiele D J, Lemontt J E. Function and autoregulation of yeast copperthionein. Science. 1985;228:685–690. doi: 10.1126/science.3887570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamiche A, Sandaltzopoulos R, Gdula D A, Wu C. ATP-dependent histone octamer sliding mediated by the chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Cell. 1999;97:833–842. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80796-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haswell E S, O'Shea E K. An in vitro system recapitulates chromatin remodeling at the PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2817–2827. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones E J. Tackling the protease problem in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:428–453. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94034-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadonaga J T. Eukaryotic transcription: an interlaced network of transcription factors and chromatin-modifying machines. Cell. 1998;92:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karin M, Najarian R, Haslinger A, Valenzuela A P, Welch J, Fogel S. Primary structure and transcription of an amplified genetic locus: the CUP1 locus of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:337–341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingston R E, Narlikar G J. ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2339–2352. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuras L, Struhl K. Binding of TBP to promoters in vivo is stimulated by activators and requires Pol II holoenzyme. Nature. 1999;399:609–613. doi: 10.1038/21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Längst G, Bonte E J, Corona D F V, Becker P B. Nucleosome movement by CHRAC and ISWI without disruption or trans-displacement of the histone octamer. Cell. 1999;97:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leblanc B P, Benham C J, Clark D J. An initiation element in the yeast CUP1 promoter is recognized by RNA polymerase II in the absence of TATA-box binding protein if the DNA is negatively supercoiled. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10745–10750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200365097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee D, Lis J T. Transcriptional activation independent of TFIIH kinase and the RNA polymerase II mediator in vivo. Nature. 1998;393:389–392. doi: 10.1038/30770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee D, Kim S, Lis J T. Different upstream transcriptional activators have distinct coactivator requirements. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2934–2939. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin D E, Fields O F, Kunisawa R, Bishop J M, Thorner J. A candidate protein kinase C gene, PKC1, is required for the S. cerevisiae cell cycle. Cell. 1990;62:213–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90360-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X-Y, Virbasius A, Zhu X, Green M R. Enhancement of TBP binding by activators and general transcription factors. Nature. 1999;399:605–609. doi: 10.1038/21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Q, Gabriel S E, Roinick K L, Ward R D, Arndt K M. Analysis of TFIIA function in vivo: evidence for a role in TATA-binding protein recruitment and gene-specific activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8673–8685. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Thiele D J. Oxidative stress induces heat shock factor phosphorylation and HSF-dependent activation of yeast metallothionein gene transcription. Genes Dev. 1996;10:592–603. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorch Y, Cairns B R, Zhang M, Kornberg R D. Activated RSC-nucleosome complex and persistently altered form of the nucleosome. Cell. 1998;94:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorch Y, Zhang M, Kornberg R D. Histone octamer transfer by a chromatin remodeling complex. Cell. 1999;96:389–392. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNeil J B, Agah H, Bentley D. Activated transcription independent of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2510–2521. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moqtaderi Z, Keaveney M, Struhl K. The histone H3-like TAF is broadly required for transcription in yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muchardt C, Yaniv M. ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling: SWI/SNF and Co. are on the job. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:187–198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Natarajan K, Jackson B M, Zhou H, Winston F, Hinnebusch A G. Transcriptional activation by Gcn4p involves independent interactions with the SWI/SNF complex and the SRB/mediator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neely K E, Hassan A H, Wallberg A E, Steger D J, Cairns B R, Wright A P H, Workman J L. Activation domain-mediated targeting of the SWI/SNF complex to promoters stimulates transcription from nucleosome arrays. Mol Cell. 1999;4:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Donohue M F, Duband-Goulet I, Hamiche A, Prunell A. Octamer displacement and redistribution in transcription of single nucleosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:937–945. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozer J, Lezina L E, Ewing J, Audi S, Lieberman P E. Association of transcription factor IIA with TATA binding protein is required for transcriptional activation of a subset of promoters and cell cycle progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2559–2570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson C L, Workman J L. Promoter targeting and chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth S Y, Dean A, Simpson R T. Yeast α2 repressor positions nucleosomes in TRP1/ARS1 chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2247–2260. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roth S Y, Simpson R T. Yeast minichromosomes. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:289–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakurai H, Fukasawa T. Activator-specific requirement for the general transcription factor IIE in yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:734–739. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnitzler G, Sif S, Kingston R E. Human SWI/SNF interconverts a nucleosome between its base state and a stable remodeled state. Cell. 1998;94:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simpson R T. Nucleosome positioning: occurrence, mechanisms and functional consequences. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1991;40:143–184. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson R T, Thoma F, Brubaker J M. Chromatin reconstituted from tandemly repeated cloned DNA fragments and core histones: a model system for study of higher order structure. Cell. 1985;42:799–808. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spadafora C, Oudet P, Chambon P. Rearrangement of chromatin structure induced by increasing ionic strength and temperature. Eur J Biochem. 1979;100:225–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Struhl K. Chromatin structure and RNA polymerase II connection: implications for transcription. Cell. 1996;84:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svaren J, Hörz W. Transcription factors vs nucleosomes: regulation of the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka S, Halter D, Livingstone-Zatchej M, Reszel B, Thoma F. Transcription through the yeast origin of replication ARS1 ends at the ABFI binding site and affects extrachromosomal maintenance of minichromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3904–3910. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thoma F, Bergman L W, Simpson R T. Nuclease digestion of circular TRP1ARS1 chromatin reveals positioned nucleosomes separated by nuclease-sensitive regions. J Mol Biol. 1984;177:715–733. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas J O, Furber V. Yeast chromatin structure. FEBS Lett. 1976;66:274–280. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiss K, Simpson R T. Cell type-specific chromatin organization of the region that governs directionality of yeast mating type switching. EMBO J. 1997;16:4352–4360. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitehouse I, Flaus A, Cairns B R, White M F, Workman J L, Owen-Hughes T. Nucleosome mobilization catalysed by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1999;400:784–787. doi: 10.1038/23506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wieland T, Faulstich H. Fifty years of amanitin. Experientia. 1991;47:1186–1193. doi: 10.1007/BF01918382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolffe A P. Sinful repression. Nature. 1997;387:16–17. doi: 10.1038/387016a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolffe A P. Chromatin. 3rd. ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yenidunya A, Davey C, Clark D J, Felsenfeld G, Allan J. Nucleosome positioning on chicken and human globin gene promoters in vitro. Novel mapping techniques. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:401–414. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zakian V A, Scott J F. Construction, replication, and chromatin structure of TRP1 RI circle, a multiple-copy synthetic plasmid derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomal DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:221–232. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]