Abstract

Since Lyme arthritis was first described in the United States, it has now been reported in many countries of Europe. However, very few strains of the causative bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, have been isolated from synovial samples. For this reason, different molecular direct typing methods were developed recently to assess which species could be involved in Lyme arthritis in Europe. We developed a simple oligonucleotide typing method with PCR fragments from the flagellin gene of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, which is able to differentiate seven different Borrelia species. Among 10 consecutive PCR-positive patients with Lyme arthritis from the northeastern France, two species were identified in synovial samples: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in 9 cases and B. garinii in 1 case. Conversely, all B. burgdorferi sensu lato species detected in 10 consecutive PCR-positive biopsies from a second set of patients with erythema migrans from the same geographical area were identified as either B. afzelii or B. garinii (P < 0.001). These results indicate that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the principal but not the only Borrelia species involved in Lyme arthritis in northeastern France.

Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme borreliosis which typically presents as brief attacks of mono- or oligoarthritis with objective joint swelling (44). Some atypical presentations have been reported, however, such as septic arthritis (14, 26) or chronic erosive polyarthritis (20). Lyme arthritis was first reported in the United States, where it represents the most frequent disseminated manifestation of this spirochete infection (43). The disease has since been documented in many countries in Europe (5, 6, 11, 13, 18, 21, 22, 24, 25, 33, 45, 47).

In recent years, molecular studies based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, 16S rRNA and flagellin gene sequencing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, arbitrarily primed PCR, restriction polymorphism of PCR products, and DNA-DNA hybridization have led to the division of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species into several genomic groups (2, 3, 7, 16, 17, 32, 37, 40, 51). Lyme borreliosis is commonly associated in Europe with three of these species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii, whereas only B. burgdorferi sensu stricto has been implicated in human disease in the United States. A new species, B. valaisiana, was recently detected by PCR in cutaneous samples from patients in The Netherlands (39), and likewise, nine Borrelia strains related to B. bissettii were obtained from cutaneous samples in Slovenia (46).

Some clinical manifestations, such as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and lymphocytoma, are very rare in the United States and occur almost exclusively in Europe. Although the real incidence of Lyme arthritis in Europe is unknown, it seems to be less frequent than neuroborreliosis. Thus, in one prospective study conducted over a 2-year period in southern Sweden, neuroborreliosis was found to be twice as frequent as Lyme arthritis (4). These findings have led to speculation that each clinical manifestation could be triggered by a separate species (1). A number of studies have been carried out to investigate this point, using either indirect methods (Western blot analysis) or direct methods (identification of the isolates or PCR-based typing assays). Using direct methods, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans has been associated mainly but not exclusively with B. afzelii (36, 39, 52), while neuroborreliosis was shown to be caused by B. garinii in 58% of cases, B. afzelii in 28%, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in 11% (9). Erythema migrans (EM) can result from infection by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, B. afzelii, and probably also B. valaisiana (8, 39, 52). Recently, several molecular studies analyzed the involvement of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in synovial samples from European patients. Different methods were used: DNA sequencing (15), reverse line blot hybridization of PCR products (49), or PCR with primers specific for each species (50). Among these reports, two German groups indicated that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii could all be involved in Lyme arthritis (15, 50), whereas a Dutch group (49) found only B. burgdorferi sensu stricto as a causative agent of Lyme arthritis.

The aim of our study was to develop a simple direct assay based on typing of PCR products and capable of detecting most of the known species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and then to apply this method to two sets of clinical samples. The first set consisted of consecutive synovial samples from Lyme arthritis patients from northeastern France; the second set consisted of consecutive cutaneous biopsies of EM lesions from patients from the same area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. burgdorferi strains.

Ten B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains, including strains belonging to all species presently known to be potentially pathogenic to humans, were used as controls to evaluate the spectra of the primers and the specificity of the different probes: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains 297 and B 31, B. garinii strains 20047 and P/Bi, B. afzelii strain VS 461, B. japonica strain HO 14, B. andersonii strain 21123, B. valaisiana strain VS 116, B. lusitaniae strain Poti B2, and B. bissettii strain DN127. All strains were grown in BSK-H medium (Sigma, Saint-Quentin, France) under the usual conditions (43).

Other bacterial strains.

The specificity of the PCR method was assessed with DNA templates from the following bacterial species isolated from clinical specimens: Aeromonas hydrophila, Bacteroides fragilis, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter aerogenes, Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi A, Serratia marcescens, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Xanthomonas maltophilia, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Borrelia hermsii, Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum (strain Nicols), and Leptospira biflexa serovar Patoc were also employed as templates. Tests were performed with DNA from a single strain of each bacterial species.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers of B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains used.

Flagellin gene sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu lato used in this study were from the EMBL/GenBank database, as follows: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 (X16833), HB19 (X75200), and GeHo (X56334); B. garinii 20047 (D82846), HT19 (D63371), HT22 (D63367), HT37 (D63369), JEM3 (D63372), JEM4 (D63364), JEM5 (D63370), and Ip90 (X75203); B. afzelii VS461 (D63365), HT61 (D63366), and ACA1 (X75202); B. japonica HO14 (D82852) and NT112 (D82853); B. andersonii 21123 (D83764), 21038 (D83763), and 19857 (D83762); B. valaisiana VS116 (D82854); B. lusitaniae PotiB2 (D82856); B. bissettii DN127 (D82857) and CA127 (D82858); B. turdi Hk501 (D82847) and OR2eL (D82848); Borrelia group Ya501 Ya501 (D82849), Ac502 (D82850), and Kt501 (D82851); and Borrelia Am501 (D82855). The number of sequences selected is representative of the known intraspecies variability of the flagellin gene sequences as reported in the phylogenetic study of Fukunaga and Koreki (17). An average of two to three sequences was selected, except for the B. garinii species, which have greater intraspecies heterogeneity, or when fewer sequences were available from the EMBL/GenBank database.

DNA extraction and amplification.

DNA was extracted from synovial specimens and Borrelia strains as previously described (28). Amplification targeting DNA of the central part of the flagellin gene was carried out by standard procedures (28), using as primers two oligonucleotides, Bbs1-1 and Bbsl-3c, specific for all B. burgdorferi sensu lato species as previously checked by comparison with nucleotide sequences from the EMBL/GenBank database. Bbs1-1 (5′-AACACACCAGCATCACTTTCAGG-3′) is located at nucleotides 475 to 496 of the coding strand, and Bbsl-3c (5′-GAGAATTAACTCCGCCTTGAGAAGG-3′) is located at nucleotides 685 to 709 complementary to the coding strand. The same precautions as in earlier work (28) were taken to avoid DNA contamination during amplification.

Oligonucleotides specific for Borrelia species.

Flagellin gene nucleotide sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu lato from the EMBL/GenBank database were aligned using MEGALIGN software (DNASTAR program; DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.) and the CLUSTAL method (23). After comparison of these sequences with those of relapsing fever borreliae, seven species-specific oligonucleotides were designed and synthesized for the following B. burgdorferi sensu lato species: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, B. afzelii, B. japonica, B. andersonii, B. valaisiana, and B. bissettii (Table 1). No probes were designed for B. lusitaniae or the remaining Borrelia genomic groups because their flagellin gene sequences did not differ enough from the other B. burgdorferi sensu lato species sequences to design a specific oligonucleotide probe. An oligonucleotide able to hybridize with all B. burgdorferi sensu lato species was also synthesized.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of the specific probes for B. burgdorferi sensu lato species

| Probe | Borrelia species | Nucleotide sequence from initiation of probe | Nucleotide location from initiation codon |

|---|---|---|---|

| BbssSD | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | GGTTCAAGAGGGTGTTCAACAGG | 630–652 |

| BgSD | B. garinii | AGGAGCTCAGGCTGCTCAGA | 603–622 |

| BafSD | B. afzelii | CTCAAGAAGAAGGAGCTCAGCAA | 644–666 |

| BjSD | B. japonica | GCCTGTTCAAGAAGGCATTCAACAG | 627–651 |

| BandSD | B. andersonii | TGTTCAAGAGGGTATTCAACAG | 630–651 |

| BvSD | B. valaisiana | ACACCTGTTCAAGAAGGTGCTCAACAG | 625–652 |

| BgpDN127SD | B. bissettii | GAAGGTGTTCAGCAAGAAGG | 637–656 |

| BbslSD | B. burgdorferi sensu lato | GCTGTAAATATTTATGCAGCTAATGTTGC | 556–584 |

Dot blot hybridization.

DNA probes were 5′ labeled with [γ32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) as described by Sambrook et al. (41). Aliquots (5 μl) from each PCR tube were spotted onto positively charged nylon membrane filters (Boehringer Mannheim), and DNA denaturation and fixation were performed as previously described (27).

A prehybridization step was carried out for 30 min at 55°C in 6× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7])–0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–0.08% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin–0.08% (wt/vol) Ficoll (Mr, 400,000)–0.08% (wt/vol) polyvinylpyrrolidone. Hybridization was then performed for 2 h in fresh prehybridization solution containing 0.5 pmol of labeled probe per ml, using hybridization temperatures ranging from 50 to 70°C depending on the probe (Table 2). The filters were then washed twice for 10 min in 2× SSPE buffer containing 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate at temperatures of 35 to 70°C (Table 2), air dried, and exposed overnight at −70°C to an X-ray film (Fujifilm NIF; Fuji) with two intensifying screens.

TABLE 2.

Hybridization and wash conditions for probes

| Probea | Hybridization temp (°C) | Wash temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| BbssSD | 64 | 50 |

| BgSD | 60 | 60 |

| BafSD | 60 | 55 |

| BjSD | 62 | 62 |

| BandSD | 60 | 63 |

| BvSD | 70 | 70 |

| BgpDN127SD | 57 | 57 |

| BbslSD | 50 | 35 |

BbssSD, BgSD, BafSD, BjSD, BandSD, BvSD, BgpDN127SD, and BbslSD, probes for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, B. afzelii, B. japonica, B. andersonii, B. valaisiana, B. bissettii, and B. burgdorferi sensu lato, respectively.

Patients and samples.

(i) Over a 4-year period (from January 1994 to October 1998), synovial fluid and/or synovium was obtained by needle puncture from a set of 12 consecutive patients with typical Lyme arthritis. Ten of the 12 patients analyzed were positive for B. burgdorferi sensu lato in synovial samples by PCR assay (28), and all cases satisfied the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the surveillance of Lyme arthritis (38). These patients had positive immunoglobulin G serology (EIA Enzygnost borreliosis; Behring, Marburg, Germany), as was confirmed by Western blot analyses using B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain 297 as an antigen (10). Five of these 10 patients had a previous history of EM, and 9 of them lived in northeastern France. Lyme disease is endemic in this area in France (34); the tick infection rate is the highest of any area in France, with an average nympheal infestation rate of 7.5% (19).

(ii) Over the same time period, cutaneous biopsies were taken from a second set of 25 patients with typical EM. Ten of these biopsies were positive for B. burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in cutaneous samples by PCR assay. The size of the analyzed samples was based on convenience.

Statistics.

Typing results for patients with Lyme arthritis and with EM were compared by Pearson's test using the Yates correction.

RESULTS

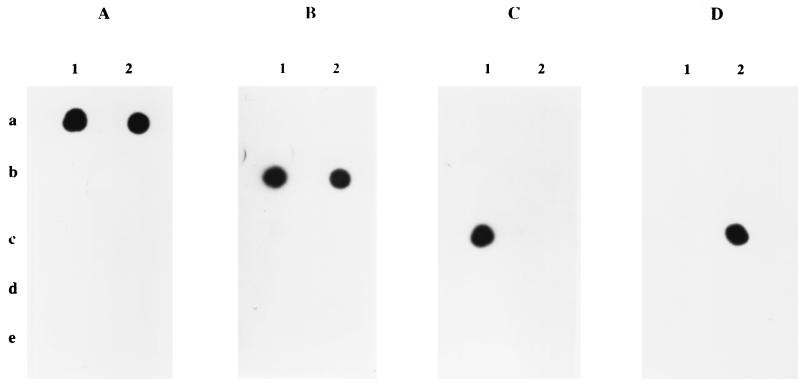

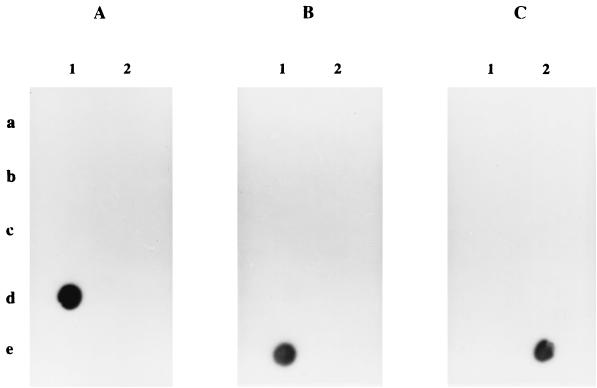

Using Bbs1-1 and Bbsl-3c as primers, DNAs from all B. burgdorferi sensu lato control strains were amplified and gave positive signals of the same intensity in hybridization tests with the Bbsl SD probe, which is specific for B. burgdorferi sensu lato (Fig. 1). No amplification was observed using other bacterial species (data not shown). The seven species-specific probes gave strong hybridization signals and negligible background levels with the DNAs of the homologous strains but no signal with the DNAs of heterologous species (Fig. 2 and 3). Stringent hybridization and wash temperatures varied from 35 to 70°C depending on the probe (Table 2), and under these conditions, the method was reliable and specific for all probes, including those corresponding to pathogenic species (Fig. 2 and 3).

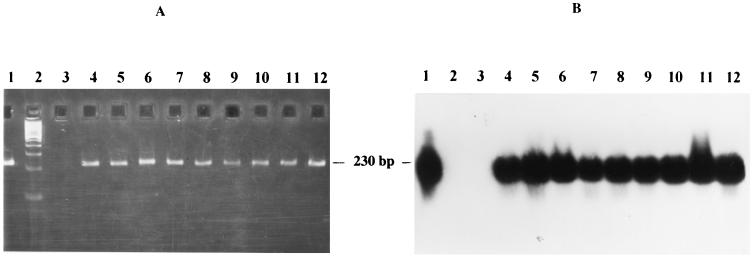

FIG. 1.

Specificity of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato PCR assay, showing agarose gel electrophoresis (A) and Southern blot analysis (B) of amplified DNAs (40 cycles) from different B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains using Bbs1-1 and Bbsl-3c as primers and BbslSD as the detection probe. DNA templates: lanes 1, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B 31; lanes 2, 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL) as DNA molecular size marker; lanes 3, B. hermsii strain HS1; lanes 4, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain 297; lanes 5, B. garinii strain 20047; lanes 6, B. garinii strain P/Bi; lanes 7, B. afzelii strain VS 461; lanes 8, B. japonica strain HO 14; lanes 9, B. andersonii strain 21123; lanes 10, B. valaisiana strain VS 116; lanes 11, B. lusitaniae strain Poti B2; lanes 12, B. bissettii strain DN 127. For each of these strains, 10 pg of DNA was used as the initial template.

FIG. 2.

Hybridization with probes specific for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (A), B. garinii (B), B. afzelii (C), and B. japonica (D). PCR products were from 10 pg of DNA as follows: 1a, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297; 2a, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31; 1b, B. garinii 20047; 2b, B. garinii P/Bi; 1c, B. afzelii VS 461; 2c, B. japonica HO14; 1d, B. bissettii; 2d, B. lusitaniae PotiB2; 1e, B. andersonii 21123; 2e, B. valaisiana VS 116.

FIG. 3.

Hybridization with probes specific for B. bissettii (A), B. andersonii (B), and B. valaisiana (C). PCR products were from 10 pg of DNA as follows: 1a, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297; 2a, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31; 1b, B. garinii 20047; 2b, B. garinii P/Bi; 1c, B. afzelii VS 461; 2c, B. japonica HO14; 1d, B. bissettii; 2d, B. lusitaniae PotiB2; 1e, B. andersonii 21123; 2e, B. valaisiana VS 116.

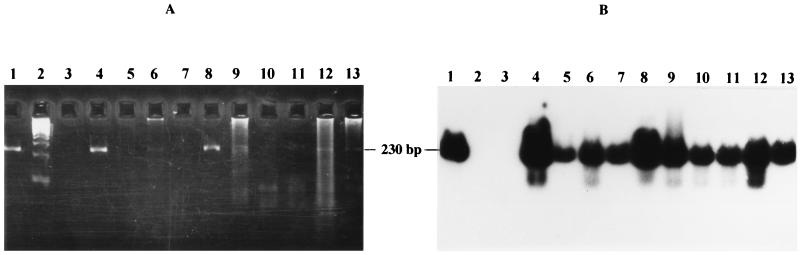

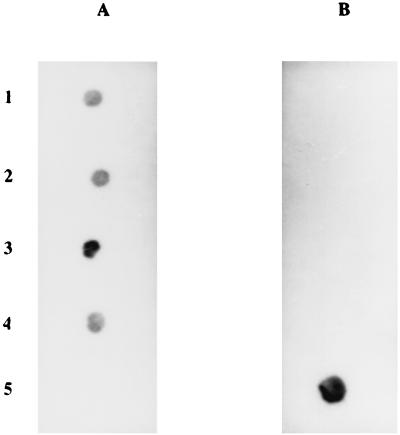

This assay was then applied to the PCR products obtained by in vitro amplification of B. burgdorferi sensu lato DNA from synovial samples (Fig. 4). Although such samples are generally considered to contain low numbers of bacteria, all tissue or liquid specimens gave easily readable signals after hybridization. Synovial samples from 9 of the 10 patients hybridized only with the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto probe (Fig. 5A), while the sample from one patient hybridized only with the B. garinii probe (Fig. 5B). This patient lives and participates in outdoor activities in northeastern France near Strasbourg. No mixed infections were observed, and no signals were obtained when hybridization was performed with probes specific for B. afzelii, B. japonica, B. andersonii, B. valaisiana, or B. bissettii (data not shown). When this typing method was applied to PCR products from the EM biopsies, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was never detected, whereas B. afzelii was detected in eight cases and B. garinii was detected in two cases. The difference between the typing results for synovial samples and for EM erythema biopsies from the same geographical area was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity of the PCR method for the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in joint samples. (A) Analysis of PCR products by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining after 40 amplification cycles; (B) Southern blot analysis after hybridization with probe Bbs1SD. Lanes 1, 300 fg of purified DNA of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain 297; lanes 2, 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL) as DNA molecular size marker; lanes 3, rheumatoid arthritis synovial sample; lanes 4 to 12, Lyme arthritis synovial samples.

FIG. 5.

Dot blots of B. burgdorferi sensu lato species with PCR products from synovial samples from five patients with Lyme arthritis. (A) Hybridization with the probe specific for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. (B) Hybridization with the probe specific for B. garinii.

DISCUSSION

We report here that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto seems to be the main etiological agent of Lyme arthritis in northeastern France. These results are in accordance with a previous serological study done by Assous et al. In that study (1), sera from 8 of 16 patients with arthritis collected over a 7-year period throughout France and tested by Western blot analysis using B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii antigens showed preferential reactivity in immunoblots with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Our results are also in accordance with those of a very recent Dutch molecular study (49). Other results were obtained in two German studies (15, 50), which reported the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii from synovial samples without any prevalence of a certain genospecies. Prior to molecular analysis, only two strains have, to our knowledge, been isolated from synovial samples in Europe, and both were identified as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (42; E. Ruzic-Sabljic, personal communication).

The number of Borrelia species known to be involved in human disease in Europe has increased since the original description of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (29). B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii have been identified (2), and more recently B. valaisiana and B. bissettii have also been implicated (39, 46). An assay allowing the detection of more than three different genospecies, including all those involved in European disease, is thus of potential interest for clinical purposes. Several methods have been described for the direct typing of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in clinical samples. Targets were the flagellin gene (35), the ospA gene (15, 50), the spacer between the 5S and 23S rRNA genes (39, 49), and the gene coding for a 26-kDa protein (50). These assays generally identify only three species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and require separate amplification for each species or DNA sequencing. Our procedure requires only one amplification for the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, after which species typing is based on a simple dot blot assay. The flagellin gene was selected as the target on account of its proven efficiency in clinical samples (28, 36) and because flagellin sequences for many known species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato were available in databases compared to plasmid target sequences. No ospA sequence for B. valaisiana, B. japonica, B. lusitaniae, or B. bissettii was available from the EMBL/GenBank database.

Typing techniques based on PCR technology have two major advantages for the clinical identification of Borrelia species involved in clinical infections. First, it is possible to detect mixed infections, as was demonstrated in two recent studies of neuroborreliosis and cutaneous manifestations (12, 39), where disease was found to reflect the infection of some ticks by several Borrelia species (30, 31). Second, there is no need to isolate the causative bacterium. Hence, these assays have the potential to detect species which could be more difficult to culture than others. In this context, it is interesting that B. valaisiana was not isolated among 58 strains obtained during an extensive 4-year Dutch study of skin samples (48), whereas this species was detected by PCR in 6 of 26 positive cutaneous samples collected in the same country (39). Our results confirm the PCR approach as a powerful method for the detection and typing of Borrelia infections in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. Postic (Paris, France) for providing the B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains, to M. Kubina for statistical analysis, to D. Herb and C. Barthel for excellent technical assistance, and to P. Dietz for photographs.

Part of this work was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique 1995.

REFERENCES

- 1.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Nevot P, Baranton G. Western blot analysis of sera from Lyme borreliosis patients according to the genomic species of the Borrelia strains used as antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01967256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belfaiza J, Postic D, Bellenger E, Baranton G, Saint Girons I. Genomic fingerprinting of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2873–2877. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2873-2877.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berglund J, Eitrem R, Ornstein K, Lindberg A, Ringner A, Elmrud H, Carlsson M, Runehagen A, Svanborg C, Norrby R. An epidemiologic study of Lyme disease in southern Sweden. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1319–1324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi G, Rovetta G, Monteforte P, Fumarola D, Trevisan G, Crovato F, Cimmino M A. Articular involvement in European patients with Lyme disease. A report of 32 Italian patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1990;29:178–180. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/29.3.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaauw I, Nohlmans L, Vandenbergloonen E, Rasker J, Vanderlinden S. Lyme arthritis in The Netherlands. A nationwide survey among rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1819–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boerlin P, Peter O, Bretz A G, Postic D, Baranton G, Piffaretti J C. Population genetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi isolates by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1677–1683. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1677-1683.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch U, Hizo-Teufel C, Bohmer R, Fingerle V, Rossler D, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains isolated from cutaneous Lyme borreliosis biopsies differentiated by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:583–589. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch U, Hizoteufel C, Boehmer R, Fingerle V, Nitschko H, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V. Three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii) identified from cerebrospinal fluid isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1072-1078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chary-Valckenaere I, Guillemin F, Pourel J, Schiele F, Heller R, Jaulhac B. Seroreactivity to Borrelia burgdorferi antigens in early rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:945–949. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.9.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper C, Muhlemann M, Wright D J, Hutchinson C A, Armstrong R, Maini R N. Arthritis as manifestation of Lyme disease in England. Lancet. 1987;1:1313–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demaerschalck I, Benmessaoud A, Dekesel M, Hoyois B, Lobet Y, Hoet P, Bigaignon G, Bollen A, Godfroid E. Simultaneous presence of different Borrelia burgdorferi genospecies in biological fluids of Lyme disease patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:602–608. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.602-608.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dournon E, Assous M. Lyme disease in France. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1986;263:464–465. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(87)80109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eichenfield A H, Goldsmith D P, Benach J L, Ross A H, Loeb F X, Doughty R A, Athreya B H. Childhood Lyme arthritis: experience in an endemic area. J Pediatr. 1986;109:753–758. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eiffert H, Karsten A, Thomssen R, Christen H J. Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi strains in Lyme arthritis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:265–268. doi: 10.1080/00365549850160918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foretz M, Postic D, Baranton G. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:11–18. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukunaga M, Koreki Y. A phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates associated with Lyme disease in Japan by flagellin gene sequence determination. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:416–421. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerster J C, Guggi S, Perroud H, Bovet R. Lyme arthritis appearing outside the United States: a case report from Switzerland. Br Med J. 1981;283:951–952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6297.951-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilot B, Degeilh B, Pichot J, Doche B, Guiguen C, Boero L, Pawlack C, Lebourdeles S. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) in Ixodes ricinus populations in France, according to a phytoecological zoning of the territory. Eur J Epidemiol. 1996;12:395–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00145304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez J, Palermo M, Maroto M C, Abellan M. Atypical bilateral symmetric erosive chronic polyarthritis in the course of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:787–789. doi: 10.1007/BF02098473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammers-Berggren S, Andersson U, Stiernstedt G. Borrelia arthritis in Swedish children: clinical manifestations in 10 children. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81:921–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzer P, Wilske B. Lyme arthritis in Germany. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1986;263:268–274. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huaux J P, Sindic C, Meunier H, Sonnet J, Bigaignon G, Hantson P, Collard P. Lyme arthritis in Belgium. Report of three cases. Clin Rheumatol. 1987;6:399–402. doi: 10.1007/BF02206839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huppertz H I. Lyme arthritis-experience in Germany. Rev Rhum (Engl Ed) 1997;64:205S–206S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs J C, Stevens M, Duray P H. Lyme disease simulating septic arthritis. JAMA. 1986;256:1138–1139. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380090066019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaulhac B, Bes M, Bornstein N, Piémont Y, Brun Y, Fleurette J. Synthetic DNA probes for detection of genes for enterotoxins A, B, C, D, E and for TSST-1 in staphylococcal strains. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaulhac B, Chary-Valckenaere I, Sibilia J, Javier R M, Piémont Y, Kuntz J L, Monteil H, Pourel J. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi by DNA amplification in synovial tissue samples from patients with Lyme arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:736–745. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson R C, Schmid G P, Hyde F W, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J. Borrelia burgdorferi sp. nov.: etiological agent of Lyme disease. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:496–497. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirstein F, Rijpkema S, Molkenboer M, Gray J S. The distribution and prevalence of B. burgdorferi genomospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Ireland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:67–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1007360422975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirstein F, Rijpkema S, Molkenboer M, Gray J S. Local variations in the distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genomospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1102-1106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeFleche A, Postic D, Girardet K, Peter O, Baranton G. Characterization of Borrelia lusitaniae sp. nov. by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:921–925. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macallan D C, Hughes C A, Bradlow A. Lyme arthritis in southern England. Br Med J. 1987;294:1062–1063. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6579.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monteil H, Jaulhac B, Piémont Y. Lyme disease and Borrelia burgdorferi infections in Europe. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1989;47:428–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Picken M M, Picken R N, Han D, Cheng Y, Strle F. Single-tube nested polymerase chain reaction assay based on flagellin gene sequences for detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:489–498. doi: 10.1007/BF01691317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picken R N, Strle F, Picken M M, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Cimperman J. Identification of three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii) among isolates from acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:211–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S) rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahn D W, Malawista S E. Lyme disease: recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:472–481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rijpkema S G T, Tazelaar D J, Molkenboer M J C H, Noordhoek G T, Plantiga G, Scouls L M, Schellekens J F P. Detection of Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii and group VS116 by PCR in skin biopsies of patients with erythema migrans and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;3:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosa P A, Hogan D, Schwan T G. Polymerase chain reaction analyses identify two distinct classes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:524–532. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.524-532.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidli J, Hunziker T, Moesli P, Schaad U B. Cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi from joint fluid three months after treatment of facial palsy due to Lyme borreliosis. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:905–906. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steere A C, Grodzicki R L, Kornblatt A N, Craft J E, Barbour A G, Burgdorfer W, Schmid G P, Johnson E, Malawista S E. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:733–740. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steere A C, Schoen R T, Taylor E. The clinical evolution of Lyme arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:725–731. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stiernstedt G, Granstrom M. Borrelia arthritis in Sweden. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1986;263:285–287. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strle F, Picken R N, Cheng Y, Cimperman J, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Picken M M. Clinical findings for patients with Lyme borreliosis caused by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with genotypic and phenotypic similarities to strain 25015. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:273–280. doi: 10.1086/514551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valesova M, Mailer H, Havlik J, Hulinska D, Hercogova J. Long-term results in patients with Lyme arthritis following treatment with ceftriaxone. Infection. 1996;24:98–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01780670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Dam A P, Kuiper H, Vos K, Widjojokusumo A, de Jongh B M, Spanjaard L, Ramselaar A C, Kramer M D, Dankert J. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Heijden I M, Wilbrink B, Rijpkema S G T, Schouls L M, Heymans P H M, van Embden J D A, Breedveld F C, Tak P P. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by reverse line blot in the joints of Dutch patients with Lyme arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1473–1480. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1473::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasiliu V, Herzer P, Rössler D, Lehnert G, Wilske B. Heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato demonstrated by an ospA-type-specific PCR in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1998;187:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s004300050079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welsh J, Pretzman C, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Baranton G, McClelland M. Genomic fingerprinting by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction resolves Borrelia burgdorferi into three distinct phyletic groups. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:370–377. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wienecke R, Zochling N, Neubert U, Schlupen E M, Meurer M, Volkenandt M. Molecular subtyping of Borrelia burgdorferi in erythema migrans and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:19–22. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12388947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]