Abstract

Introduction

The results of studies of tocilizumab (TCZ) in COVID‐19 are contradictory. Our study aims to update medical evidence from controlled observational studies and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on the use of TCZ in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19.

Methods

We searched the following databases from January 1, 2020 to April 13, 2021 (date of the last search): MEDLINE database through the PubMed search engine and Scopus, using the terms (“COVID‐19" [Supplementary Concept]) AND "tocilizumab" [Supplementary Concept]).

Results

Sixty four studies were included in the present study: 54 were controlled observational studies (50 retrospective and 4 prospective) and 10 were RCTs. The overall results provided data from 20,616 hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: 7668 patients received TCZ in addition to standard of care (SOC) (including 1915 patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) with reported mortality) and 12,948 patients only receiving SOC (including 4410 patients admitted to the ICU with reported mortality). After applying the random‐effects model, the hospital‐wide (including ICU) pooled mortality odds ratio (OR) of patients with COVID‐19 treated with TCZ was 0.73 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.56–0.93). The pooled hospital‐wide mortality OR was 1.25 (95% CI = 0.74–2.18) in patients admitted at conventional wards versus 0.66 (95% CI = 0.59–0.76) in patients admitted to the ICU. The pooled OR of hospital‐wide mortality (including ICU) of COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ plus corticosteroids (CS) was 0.67 (95% CI = 0.54–0.84). The pooled in‐hospital mortality OR was 0.71 (95% CI = 0.35–1.42) when TCZ was early administered (≤10 days from symptom onset) versus 0.83 (95% CI 0.48–1.45) for late administration (>10 days from symptom onset). The meta‐analysis did not find significantly higher risk for secondary infections in COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ.

Conclusions

TCZ prevented mortality in patients hospitalized for COVID‐19. This benefit was seen to a greater extent in patients receiving concomitant CS and when TCZ administration occurred within the first 10 days after symptom onset.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID‐19, meta‐analysis, SARS‐CoV‐2, systematic review, tocilizumab

1. INTRODUCTION

After more than 1 year into the COVID‐19 pandemic, only a few therapies have withstood the inexorable push of scientific evidence. Basically, treatments aimed at blocking the cytokine storm that accompanies COVID‐19 persist, including corticosteroids (CS) and tocilizumab (TCZ).

Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG1 subclass that inhibits signaling of interleukin 6 (IL‐6). A pleiotropic cytokine, IL6, mediates inflammation, immune response, and hematopoiesis and has been implicated in a range of lymphoproliferative and autoimmune diseases. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is a potentially life‐threatening complication of chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T)‐cell therapy and of autoimmune diseases. CRS is characterized by fever, arthralgia, headache, rash, and diarrhea in mild cases, and a systemic inflammatory response with multiple organ involvement in severe cases. The pathophysiology stems from activation of lymphocytes and myeloid cells with the release of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interferon gamma (IFNγ), IL‐1 beta (IL‐1β), IL‐2, IL‐6, IL‐8, and IL‐10. IL‐6 is thought to be a central mediator of toxicity in CRS. Trans‐signaling is particularly important in CRS, with high levels of IL6 leading to enhanced downstream signaling in many cells. 1

Although in the case of CS, there is more unanimity in favor of their benefits, 2 published evidence of TCZ treatment in patients with COVID‐19 has been still controversial, lengthening the debate on its use to this day. Interestingly, there are almost a hundred uncontrolled 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 and controlled 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 observational studies published to date, in which TCZ generally improved survival in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. On the contrary, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of TCZ in COVID‐19 have been reported scarcely, with mixed results. 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107

A few systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (SRMAs) of TCZ in COVID‐19 have been published, also with changing results as new studies are published. 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 Our study aims to update published evidence from controlled observational studies and trials on the effect of TCZ use in different subgroups of patients with COVID‐19 requiring hospitalization.

2. METHODS

This report describes the results of a systematic review and meta‐analysis following the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) statement. 122 The protocol was published in the National Institute for Health Research international register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number CRD42020204934). A clinical question under the Population‐Intervention‐Comparison‐Outcome (PICO) framework format was created (Supporting Information S1).

2.1. Data sources and searches

The search strategy was developed by three investigators (M.R‐R., C.G.F., and X.C.), which was revised and approved by the other investigators (J.M.M‐L., A.M, F.F., N.A.H., J.A‐A, L.S., and J.R.). Preprint articles were not included in the present study. We searched the following databases from January 1, 2020 to April 13, 2021 (date of the last search): MEDLINE database through the PubMed search engine and Scopus, using the terms (“COVID‐19" [Supplementary Concept]) AND "tocilizumab" [Supplementary Concept]).

2.2. Study selection

Full‐text observational studies and trials in any language reporting beneficial or harmful outcomes on the use of TCZ in adults hospitalized with COVID‐19 were included. Six investigators (M.R‐R., J.M.M‐L., A.M., N.A.H., J.A‐A, and L.S.) independently screened each record title and abstract for potential inclusion. Restriction of publication types was manually applied: secondary analyses of previously reported trials, protocols, and abstracts‐only were excluded. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for full‐text review. Two investigators (M.R‐R. and F.F.) read the full text of the abstracts selected. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by a third investigator (X.C.).

Publications were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) the study reported data on adults ≥18 years with COVID‐19, diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and admitted hospital‐wide or in intensive care units (ICUs); (2) the study design was an observational or experimental investigation providing original data on TCZ use in COVID‐19, either intravenous or subcutaneous; and (3) the study data collection finished after January 1, 2020.

Studies reported as “case–control studies,” in which subjects from the control group also presented COVID‐19, just as those from the TCZ group, were also included in the present review. Studies focusing on a sole subgroup of patients (e.g., renal transplant recipients) were excluded. Furthermore, studies with overlapping data (e.g., the same series reported in different studies) were rejected to avoid bias due to data overexpression. In such cases, the latest and/or largest study was selected. For this purpose, a careful revision was performed of patients’ origins included in studies from the same country not to include patients from the same hospital. When patients came from the same hospital, the larger study was chosen. The search was completed by the bibliography review of every article selected for full‐text examination.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators (M.R‐R. and J.M.M‐L.) independently abstracted the following details: study characteristics, including setting; intervention or exposure characteristics, including medication dose and duration; patient characteristics, including the severity of disease; and outcomes, including mortality, admission to the ICU, adverse events such as secondary infections, and length of hospital stay. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion in consultation with a third investigator (X.C.).

Early administration of TCZ was set before Day 10 from symptom onset. The time chosen was arbitrary considering that patients are admitted around Day 7 from symptom onset and that inflammatory escalation usually occurs in the second week of illness. Thus, it would give a margin of 2–3 days for early administration of TCZ on the first days of admission.

Quality assessment was performed by three investigators (M.R‐R., C.G.F., and N.A.H) using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies 123 and the risk of bias for trials. 124 In case of disagreement, a third author (J.R.) independently determined the quality assessments.

2.4. Data synthesis and analysis

Categorical variables were described as sample size‐weighted absolute numbers and percentages. When the number of events and the sample size were small (and followed a Poisson distribution), confidence intervals were estimated using Wilson's method. 125 , 126 We carried out a meta‐analysis of the pooled mortality odds ratio (OR) of mortality in TCZ‐treated patients versus non‐TCZ‐treated patients (OR of 1).

2.5. Statistical analysis

We conducted random‐effects meta‐analysis assuming that there is an underlying effect for each study which varies randomly across studies, with the resulting overall effect an average of these. 127 Studies with 0 events in one arm were not included in the meta‐analysis as recommended, using restricted maximum likelihood (REML), stratified by study design. 128 Aggregated effect sizes were calculated as combined ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Homogeneity across trials was assessed using Cochran's Q test with nominal level 0.05 and quantified the percentage of variability between as indicated by Higgins I2 parameter and between‐study variability by the Tau2. I 2 values over 50% were considered as presenting substantial heterogeneity.

Forest plots were depicted accordingly. Publication bias was assessed visually based on contour funnel plot symmetry, with asymmetry suggesting possible publication bias, and using the Begg and Egger test in the meta‐analysis and p‐values ≤0.05 as indications that publication bias existed. 129 The presence of influential small‐study effects was assessed using Peter's test for log‐odds ratios, and significance would be achieved if there was a correlation between the sample size and odd ratios, indicating potential for publication bias. 130 Statistical significance for treatment effect size and meta‐regression parameters was pre‐defined at p > 0.05. Additionally, potential outlier studies were assessed graphically using L’Abbé plots. 131 When outliers were detected, we conducted sensitivity analysis removing them from the aggregated results. We performed meta‐regression analysis sources of heterogeneity when it occurred. We tested for potential factors adding heterogeneity as covariates using a mixed model (random‐effects meta‐regression model). Factors included patient age, the percentage of male patients, days since symptom onset, length of treatment on corticosteroids, NOS value, and observed risk in the control group. The univariate linear meta‐regression model was as follows: log (ORi) = B0 + B1Xi + µi + ei, where logORi is the effect size in the ith study, B0 is model intercept, B1 is the regression coefficient capturing the association between OR and study variable under examination, Xi is the study variable which is hypothesized associate effect size, µi is the study i random effect, and ei error as estimated in the random‐effects model. Thus, B1 represents the amount of heterogeneity that can be decomposed according to a certain study characteristic and can be interpreted as the logOR (or, if exponentiated, directly as the OR) associated with that effect. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA Statistical Software release 16.0, College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.

3. RESULTS

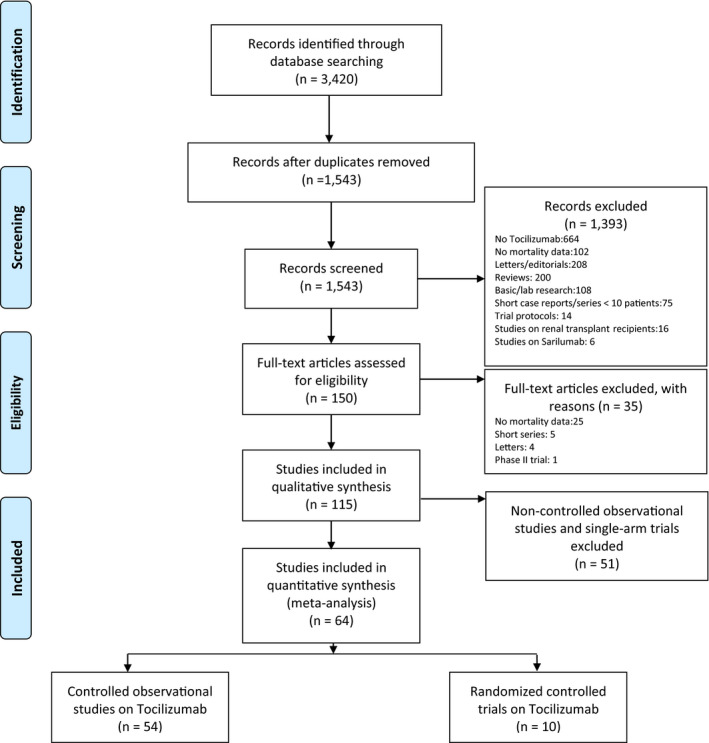

A total of 3420 articles were identified in our search. Of these, 150 qualified for full‐text review following title and abstract screening, of which 64 studies 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 99 , 100 , 103 were included in the analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram is detailed in Figure 1. The majority of included studies were carried out in different hospitals from countries in America and Europe, such as the United States (US) 46 , 47 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 61 , 67 , 68 , 70 , 76 , 82 , 84 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 92 , 94 , Italy (ITA) 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 48 , 49 , 58 , 60 , 69 , 77 , 79 , 91 , 95 , Spain (SPA) 40 , 42 , 63 , 64 , 71 , 75 , 78 , 83 , 85 , and France (FRA). 56 , 57 , 59 , 62 , 96 A lesser number was conducted in Sweden (SWE) 50 , India (IND) 72 , 81 , 93 , 105 , Iran 97 , 98 , Russia (RUS) 66 , Brazil (BRA) 100 , Pakistan (PAK) 80 , Indonesia (IDN) 73 , and China (CHI) 65 , 74 , 106 . The distribution of the studies worldwide is shown in Supporting Information S2.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

3.1. Search results

Of the total 64 studies included, 54 were controlled observational cohort studies (50 retrospective and 4 prospective) and 10 were RCTs. Four single‐arm, open‐label trials have been included in tables but not in the analyses. The risk of bias of the included RCTs is shown in Supporting Information S3. After removing the overlapping studies, 57 studies remained: 47 observational (44 retrospective and 3 prospective) and 10 RCTs.

The overall results provided data from 20,616 hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: 7668 patients treated with TCZ in addition to standard of care (SOC) (including 1915 patients admitted to the ICU with reported mortality) and 12,948 patients only received SOC (including 4410 patients admitted to the ICU with reported mortality). SOC was basically antiviral therapy (remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir), antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine), or azithromycin. As of mid‐2020, CS were accepted as SOC. This is reflected in studies with 100% or close to 100% use of CS in the control group. Anyway, the possible effect due to CS has been adjusted in the present study. A comparison between the TCZ group and the control group is detailed in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Of the TCZ group, 5271 patients (68.8%) were male, with a mean age of 62.4 (standard deviation (SD) 15.1) and median age of 61.8 [interquartile range (IQR) 58–63] years, according to the data provided. TCZ was given as a single dose in 2547/3345 patients (76.1%) and as two or more doses in 798/3345 (23.9%) patients.

TABLE 1.

Controlled studies: General data

| Author | Country | Type of study | NOS | N TCZ/controls | Study period (2020) | TCZ criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez‐Baño et al. 40 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 8 |

88/344 151/344 |

FEB 2‐MAR 31 | ≥38°C + increase in oxygen support to maintain SpO2>92%+ 1 out of: ferritin>2000 ng/ml, D‐dimer>1500 mcg/ml, IL6>50 pg/ml |

| Quartuccio et al. 41 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 42/69 | FEB 29‐APR 6 | High CRP and IL6 |

| Martínez‐Sanz et al. 42 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 260/969 | JAN 31‐APR 23 | NA |

| Guaraldi et al. 43 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 179/365 | FEB 21‐APR 30 | ≥30 bpm+SpO2<93%+PaO2/FiO2<300 mmHg |

| Campochiaro et al. 44 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 32/33 | MAR 13‐MAR 19 | SpO2≤92% + PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg +LDH>220 U/l + CRP≥100 mg/l or ferritin ≥900 ng/ml |

| Colaneri et al. 45 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 21/91 | MAR 14‐MAR 27 | CRP>5 mg/dl+procalcitonin<0.5 ng/mL+PaO2/FiO2<300 mmHg+ALT<500 U/L. |

| Price et al. 46 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 153/86 | MAR 10‐MAR 31 | O2 ≥ 3 l to maintain SpO2>93% or MV |

| Maeda et al. 47 | US | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 23/201 | MAR 13‐MAR 31 | NA |

| Capra et al. 48 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 62/23 | MAR 13‐APR 2 | 1 out of:≥30 bpm+SpO2≤93%+PaO2/FiO2≤300 mmHg |

| Rossotti et al. 49 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 74/148 | MAR 13‐APR 3 | ≥30 bpm + SpO2 ≤ 93% + PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg or ICU + CRP>1 mg/dl or IL−6 > 40 pg/ml or D‐dimer >1.5 mcg/ml or ferritin >500 ng/ml |

| Eimer et al. 50 | SWE | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 22/22 | MAR 11‐APR 15 | SpO2<94 on 5l O2 + 1 out of: CRP > 100 mg/L, LDH > 8 µkat/L, IL6 > 40 ng/L, D‐dimer>2 mg/L, troponin T > 15 ng/L, ferritin>500 µg/L |

| Kimmig et al. 51 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 54/57 | MAR 1‐APR 27 | Progressive clinical deterioration +inflammation markers |

| Tsai et al. 52 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 66/66 | MAR 1‐MAY 5 | SpO2≤94% + ferritin > 300 mcg/ml |

| Kewan et al. 53 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 28/23 | MAR 13‐APR 19 | CRP ≥ 3 g/dl or ferritin>400 ng/ml |

| Patel K et al. 54 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 42/41 | MAR 16‐APR 17 | NA |

| Rojas‐Marte et al. 55 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 96/97 | MAR 8‐APR 25 | O2 mask/HFNC up to 10l to maintain SpO2 ≥ 95% or MV |

| Roumier et al. 56 | FR | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 49/47 | MAR 9‐APR 11 | >6l O2 + high CRP |

| Rossi et al. 57 | FR | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 106/140 | MAR 23‐NA | SpO2≤96%+on 6l O2+non‐ICU |

| Potere et al. 58 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 40/40 | MAR 28‐APR 21 | Pneumonia + CRP ≥ 20 mg/dl + SpO2 < 90% |

| Klopfenstein et al. 59 | FR | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 30/176 | APR 1‐MAY 11 | ≥4 l/min O2 + ≥2 out of: high ferritin/CRP/D‐dimer/LDH and lymphopenia |

| Canziani et al. 60 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 64/64 | FEB 23‐MAY 9 | Respiratory worsening + High CRP, ferritin, CK, ALT, D‐dimer, or lymphopenia |

| Biran et al. 61 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 210/420 | MAR 1‐APR 22 | ICU |

| Albertini et al. 62 | FR | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 22/22 | APR 6‐APR 21 | ≥5l O2 + high CRP |

| Galván‐Román et al. 63 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 58/88 | FEB 24‐MAR 23 | MV+SOFA≥3+IL6>40 pg/ml or D‐dimer >1500 ng/ml |

| Moreno‐Pérez et al. 64 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 77/159 | MAR 12‐MAY 2 | Respiratory failure+IL6>40 pg/ml, ferritin>1000 mg/l, CRP>5 mg/dl, lymphocytes<900/mm3, LDH>300 U/l or D‐dimer>500 mcg/ml |

| Zheng et al. 65 | CHI | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 92/89 | JAN‐FEB | Pulmonary progression + high IL6 |

| Moiseev et al. 66 | RUS | Retrospective cohort | 6 |

83/54 76/115 |

MAR 16‐MAY 5 | Respiratory support + ICU+high CRP |

| Roomi et al. 67 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 32/144 | MAR 1‐MAY 30 | NA |

| Holt et al. 68 | US | Prospective cohort | 6 | 32/30 | NA | NA |

| Menzella et al. 69 | ITA | Prospective cohort | 7 | 41/38 | MAR 10‐APR 14 | NA |

| Gupta et al. 70 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 419/3492 | MAR 4‐MAY 10 | ICU admission |

| Masiá et al. 71 | SPA | Prospective cohort | 7 | 89/121 | MAR 10‐APR 17 | Respiratory progression + inflammation: lymphopenia or high IL6, ferritin, D‐dimer or CRP |

| Gokhale et al. 72 | IND | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 70/91 | APR 20‐JUNE 5 | Inflammatory markers + SpO2 ≤ 94% despite O2 5 l/min or PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg |

| Widysanto et al. 73 | IDN | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 14/16 | NA | NA |

| Tian et al. 74 | CHI | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 65/130 | JAN 20‐MAR 18 | Pneumonia + elevated IL−6 |

| Ruiz‐Antorán 75 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 268/238 | MAR 3‐APR 20 | Pneumonia at ward + Brescia‐COVID scale 2–3 + 1 of: IL6 > 40 pg/ml or LDHx2 or high CRP or D‐dimer > 1500 ng/ml or lymphocytes <1200/µl or ferritin > 500 ng/ml |

| Fisher et al. 76 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 45/70 | MAR 10‐APR 2 | HFNC or higher + cytokine storm |

| Castelnovo et al. 77 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 50/62 | MAR 6‐MAY 30 | CPAP with FiO2 > 40% or VMK > 50% + D‐dimer > 1500 ng/ml or ferritin > 500 ng/ml |

| Buzón‐Martín et al. 78 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 163/211 | MAR 3‐MAY 7 | ARDS + ferritin >1000 ng/ml and/or IL6 > 50 pg/ml |

| Cavalli et al.a 79 | ITA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 55/275 | FEB 25‐MAY 20 | Hyperinflammation |

| Chachar et al. 80 | PAK | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 33/60 | MAY 12‐JUN 12 | Cytokine storm |

| Gokhale et al. 81 | IND | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 151/118 | MAR 31‐JUL 5 | Bilateral pneumonia +high CRP, LDH, ferritin |

| Huang et al. 82 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 55/41 | MAR 1‐MAY 18 | SpO2<90% +2 out of: IL6>10 pg/ml, CRP > 35 mg/l,ferritin > 500 ng/ml, D‐dimer > 1 mcg/l, LDH > 200 U/l |

| López‐Medrano et al. 83 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 80/181 | MAR 3‐MAY 1 | 1 out of: ≥30 bpm + SpO2 <92%, CRP >10 mg/dl IL6 >40 pg/ml, D‐dimer >1000 ng/ml |

| Mehta et al. 84 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 33/74 | MAR 2‐APR 14 | Pneumonia + elevated inflammatory markers |

| Van den Eynde et al. 85 | SPA | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 21/118 | MAR 9‐APR 9 | Severe respiratory illness + 1 out of ferritin >700 ng/ml or D‐dimer >2000 ng/ml |

| Ip et al. 86 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 134/413 | MAR 1‐MAY 5 | ICU admission |

| Hill et al. 87 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 43/45 | MAR 19‐APR 24 | Respiratory failure +IL6x5 |

| Lewis et al. 88 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 497/497 | MAR 1‐APR 24 | NA |

| Petit et al. 89 | US | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 74/74 | MAR 1‐MAY 25 | Progressing hypoxia + D‐dimer > 2 mg/l, CRP > 100 mg/l or ferritin > 600 mcg/l |

| Somers et al. 90 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 78/76 | MAR 9‐APR 20 | Invasive mechanical ventilation |

| Mikulska et al. 91 | ITA | Prospective cohort | 8 | 29/66 | MAR‐MAY | Severe pneumonia + systemic inflammation |

| Okoh et al. 92 | US | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 20/40 | MAR 10‐APR 10 | High ferritin, CRP, LDH or lymphopenia |

| Nasa et al. 93 | IND | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 22/63 | MAR 15‐MAY 15 | ICU |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BRA, Brazil; CHI, China; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; FR, France; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; IDN, Indonesia; IL6, interleukin 6; IND, India; ITA, Italy; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MV, mechanical ventilation; NA, not applicable/available; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; SWE, Sweden; TCZ, tocilizumab; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

aMix of TCZ and Sarilumab.

TABLE 2.

Controlled studies. Drugs and outcomes

| Author |

Age (years) TCZ patients Mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

Males TCZ n (%) |

Days from onset to TCZ infusion Mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

TCZ doses |

TCZ infusion 1/ ≥2 |

CS TCZ/controls n (%) |

Remdesivir TCZ/controls n (%) |

Follow‐up, days Mean (SD) or median [IQR] |

Mortality TCZ/controls n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez‐Baño et al. 40 | 66 [56–72] | 64 (72.7) | 10 [8–13] | NA | NA | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 21 [16–21] | 2 (2.3) vs. 41 (11.9) |

| 65 [58–74] | 109 (71.9) | 11 [8–13] | 88 (100) vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 20 [11–21] | 19 (12.6) vs. 41 (11.9) | |||

| Quartuccio et al. 41 | 62.4 (11.8) | 33 (78.6) | 8.4 (3.7) | 8 mg/kg iv | 42/0 | 16 (38.1) vs. 0 | 3 (7.1) vs. 0 | NA | 4 (9.5) vs. 0 |

| Martínez‐Sanz et al. 42 | 65 [55–76] | 191 (73) | NA | 600–800 mg iv | NA | 242 (93) vs. 340 (35) | 0 vs. 0 | 13 [10–17] | 61 (23) vs. 120 (12) |

| Guaraldi et al. 43 | 64 [54–72] | 127 (71) | 7 [4–10] | 8 mg/kg iv or 162 mg sc | 0/179 | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 12 [6–17] | 13 (7) vs. 73 (20) |

| Campochiaro et al. 44 | 64 [53–75] | 29 (91) | 11 [8–14] | 400 mg iv | 23/9 | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 28 (NA) | 5 (16) vs. 11 (33) |

| Colaneri et al. 45 | 62.3 [18–68] | 19 (90.5) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | 21/0 | 21 (100) vs. 91 (100) | 0 vs. 0 | 7 (NA) | 5 (23.8) vs. 19 (20.9) |

| Price et al. 46 | 65 [NA] | 88 (58) | 7 [4.5–10] | 8 mg/kg iv | NA | 47 (31) vs. 1 (1.2) | 0 vs. 0 | 12 [8–22] | 23 (15) vs. 10 (11.6) |

| Maeda et al. 47 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 8 (33.3) vs. 33 (16.4) |

| Capra et al. 48 | 63 [54–73] | 45 (73) | NA | 400 mg iv | 62/0 | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 9 [5–19] | 2 (3.2) vs. 11 (47.8) |

| Rossotti et al. 49 | 59 [51–71] | 61 (82.4) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | NA | 0 vs. 0 | 7(9.5) vs. 12 (8.1) | 7 (NA) | 8 (11.8) vs. NA |

| Eimer et al. 50 | 60.5 [48.5–64] | 21 (95.5) | 10.5 [8–13.5] | 8 mg/kg iv | NA | 5 (22.7) vs. 8 (36.3) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 5 (22.7) vs. 7 (31.8) |

| Kimmig et al. 51 | 64.5 (13.6) | 37 (68.5) | NA | 160–800 mg iv | NA | 13 (24.1) vs. 8 (14) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 19 (35.2) vs. 11 (19.3) |

| Tsai et al. 52 | 62.4 (13.5) | 46 (69.7) | NA | 400–800 mg iv | 62/4 | 12 (18.2) vs. 5 (7.6) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 18 (27.3) vs. 18 (27.3) |

| Kewan et al. 53 | 62 [53–71] | 20 (71) | NA | 4–8 mg/kg iv | 28/0 | 20 (71) vs. 11 (47.8) | 0 vs. 0 | 11 [6–22] | 3 (11) vs. 2 (9) |

| Patel K et al. 54 | 68 [NA] | 21 (50) | NA | NA | NA | 12 (29) vs. 14 (34.1) | NA | 19 [14–25] | 11 (26.2) vs. 11 (26.8) |

| Rojas‐Marte et al. 55 | 58.8 (13.6) | 74 (77.1) | NA | NA | 96/0 | 41(42.7) vs. 32 (33) | 12(12.5) vs.9(9.3) | NA | 43 (44.8) vs. 55 (56.7) |

| Roumier et al. 56 | 57.8 (11.5) | 40 (82) | 10 (3) | 8 mg/kg iv | 34/15 | 8 (16.3) vs. 6 (12.8) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 5 (10.2) vs. 6 (12.8) |

| Rossi et al. 57 | 64.3 (13) | 70 (66) | 8.3 (4.2) | 400 mg iv | 106/0 | 43 (40.6) vs. 47 (33.6) | 0 vs. 0 | 28 (NA) | 36 (34) vs. 80 (57.1) |

| Potere et al. 58 | 56 [50–73] | 26 (65) | NA | 324 mg sc | 0/40 | 26 (65) vs. 23 (57.5) | 0 vs. 0 | 35 (NA) | 2 (5) vs. 11 (27.5) |

| Klopfenstein et al. 59 | 75.7 (11.3) | 21 (70) | 11.7 (5–21) | 8 mg/kg iv | 3/27 | 16 (53) vs. 39 (22) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 8 (26.7) vs. 66 (37.5) |

| Canziani et al. 60 | 63 (10) | 47 (73) | 13 (5) | 8 mg/kg iv | 3/61 | 31 (48) vs. 26 (40.6) | 0 vs. 0 | 30 (NA) | 17 (27) vs. 24 (38) |

| Biran et al. 61 | 62 [53–71] | 155 (74) | 9 [6–12] | 400 mg−8 mg/kg iv | 185/25 | 97 (46) vs. 191 (45) | 0 vs. 0 | 22 [11–53] | 102 (49) vs. 256 (61) |

| Albertini et al. 62 | 64 (41–80) | 16 (72.7) | 10 (3–21) | 600–800 mg | 2/20 | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | 14 (NA) | 3 (13.6) vs. 2 (9.1) |

| Galván‐Román et al. 63 | 61 [54–70] | 40 (69) | 11 [8–12.5] | 8 mg/kg iv | 0/58 | 38 (67) vs. 47 (55) | 0 vs. 0 | 61 [58–64] | 14 (24.1) vs. 16 (18.2) |

| Moreno‐Pérez et al. 64 | 62 [53–72] | 50 (64.9) | 10 [7.5–12] | 400–600 mg iv | NA | NA | 0 vs. 0 | 83 [78–86.5] | 10 (12.9) vs. 3 (1.9) |

| Zheng et al. 65 | 68.8 (25–87) | 57 (62) | NA | 4–8 mg/kg iv | NA | NA | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 9 (9.8) vs. 1 (1.1) |

| Moiseev et al. 66 | 56 [48–63] | 56 (67.5) | NA | 400 mg iv | NA | NA | NA | NA | 27 (32.5) vs. 12 (22.2) |

| 60 [53–67] | 42 (55.3) | 47 (61.8) vs. 73 (63.5) | |||||||

| Roomi et al. 67 | 65.5 (NA) | 60 (72.3) | NA | NA | NA | 26 (86.7) vs. 4 (13.3) | NA | NA | 6 (18.8) vs. 13 (9) |

| Holt et al. 68 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10 (31.3) vs. 9 (30) |

| Menzella et al. 69 | 63.3 (10.6) | 29 (71) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv or 162 mg sc | 0/41 | 28 (68) vs. 27 (71) | NA | NA | 10 (24) vs. 20 (53) |

| Gupta et al. 70 | 62 [53–73] | 271 (64.7) | NA | NA | NA | 62 (14.8) vs. 467 (13.4) | 0 vs. 0 | 27 [14–37] | 125 (28.9) vs. 1419 (40.6) |

| Masiá et al. 71 | 62 [56.8–77] | 54 (71.1) | NA | 400–600 mg iv | NA | 24 (31.6) vs. 3 (4.8) | 0 vs. 1 (0.7) | NA | 2 (2.6) vs. 8 (12.9) |

| Gokhale et al. 72 | 52 [44–57] | 47 (67.1) | NA | 400 mg iv | 70/0 | 70 (100) vs. 91 (100) | 0 vs. 0 | 16 [4.5–50] | 33 (47.1) vs. 61 (67) |

| Widysanto et al. 73 | 58.7 (10.1) | 12 (75) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 (28.6) vs. 6 (37.5) |

| Tian et al. 74 | 71 [63–75] | 48 (73.9) | NA | 4–8 mg/kg iv | 49/16 | 52 (81.3) vs. 94 (72.3) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 14 (21.5) vs. 42 (32.3) |

| Ruiz‐Antorán 75 | 65 (11.7) | 184 (68.7) | 11.7 (5.2) | 4–8 mg/kg iv | 154/114 | 87 (32.5) vs.26 (10.9) | 1 (0.4) vs. 1 (0.4) | 12 [7–18] | 45 (16.8) vs.75 (31.5) |

| Fisher et al. 76 | 56.2 (14.7) | 29 (64.4) | NA | 4–8 mg/kg iv | 42/3 | 33 (73.3) vs. 55 (78.6) | NA | 30 [NA] | 13 (28.9) vs. 28 (40) |

| Castelnovo et al. 77 | 61 (9) | 35 (70) | NA | NA | 1/49 | 50 (100) vs. 37 (59) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 6 (12) vs. 21 (33.9) |

| Buzón‐Martín et al. 78 | 64.5 [57.5–72.5] | 130 (79.6) | NA | NA | NA | 162(99.3) vs.188(89.1) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 13 (8) vs. 51 (24.2) |

| Cavalli et al.a 79 | 58 [52–74] | 48 (87) | NA | 400 mg iv | 46/9 | 6 (3.3) vs. 54 (19.6) | 0 vs. 0 | 28 [NA] | 45 (82) vs. 187 (68) |

| Chachar et al. 80 | 60 [36–74] | 22 (66.7) | NA | 800 mg iv | NA | 0 vs. 60 (100) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 6 (18.2) vs. 4 (6.7) |

| Gokhale et al. 81 | 53 [44–60] | 107 (70.9) | NA | 400 mg iv | 151/0 | 151 (100) vs. 118 (100) | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 79 (52.3) vs. 74 (62.7) |

| Huang et al. 82 | 63.6 (14.8) | 36 (81.8) | NA | 400 mg iv | 55/0 | 1 (1.8) vs. 1 (2.4) | 8 (14.5) vs. 1(2.4) | NA | 8 (14.5) vs. 15 (36.6) |

| López‐Medrano et al. 83 | 74.4 (7) | 45 (56.2) | 11 [9–16] | 400 mg iv | NA | 80 (100) vs.181 (100) | 7 (8.8) vs. 1 (0.6) | 28 [NA] | 22 (27.5) vs. 86 (47.5) |

| Mehta et al. 84 | 54.6 (NA) | 25 (76) | NA | 400–800 mg iv | 30/3 | 0 vs. 0 | 2 (6.1) vs. 4 (5.9) | 28 [NA] | 8 (24) vs.8 (11) |

| Van den Eynde et al. 85 | 61.5 [51.2–71.4] | 16 (76.2) | NA | 400–800 mg iv | NA | 0 vs. 0 | NA | NA | 7 (33.3) vs. 69 (58.5) |

| Ip et al. 86 | 62 [53–70] | 99 (73.9) | NA | 4–8 mg/kg iv | 104/30 | 89 (25) vs. 263 (75) | NA | NA | 61/134 vs. 231/413 |

| Hill et al. 87 | NA | 30 (70) | NA | 400 mg iv | 40/3 | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 28 [NA] | 9 (21) vs. 15 (33) |

| Lewis et al. 88 | 61 [52–69] | 352 (70.8) | NA | 400 mg iv | 497/0 | 257 (51.7) vs. 474 (15.4) | NA | NA | 145 (29.2) vs. 211 (42.5) |

| Petit et al. 89 | 66 (13.7) | 43 (58) | 9 (NA) | 400 mg iv | 66/8 | NA | 21(28)vs.27(36.5) | 58 (NA) | 29 (39) vs. 17 (23) |

| Somers et al. 90 | 55 (14.9) | 53 (68) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | 78/0 | 23 (29) vs. 15 (20) | 2 (3) vs. 2 (3) | 47 [NA] | 14 (18) vs. 27 (36) |

| Mikulska et al. 91 | 67.4 [NA] | 24 (82.8) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv or 162 mg sc | 22/7 | 0 vs. 0 | 0 vs. 0 | NA | 4 (14.2) vs. 19 (28.1) |

| Okoh et al. 92 | 54 (41.6) | 10 (50) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | NA | 1 (5) vs. 8 (20) | NA | NA | 2 (10) vs. 3 (8) |

| Nasa et al. 93 | 51 (NA) | 22 (100) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | 0/22 | NA | NA | 28 [28] | 2 (9.1) vs. 36 (57.1) |

Abbreviations: CS, corticosteroids; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable/available; SD, standard deviation; TCZ, tocilizumab.

a47 patients treated with TCZ and 3 with Sarilumab.

TABLE 3.

Secondary outcome in controlled studies: Length of stay, ICU admission, ICU vs. ward mortality, and infections

| Author | Length of stay TCZ/controls days, mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

ICU admission TCZ vs. controls, n/N (%) |

TCZ prescribed at ICU mortality TCZ vs. controls, n/N (%) |

TCZ prescribed at the ward mortality TCZ vs. controls, n/N (%) |

Infections TCZ vs. controls, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez‐Baño et al. 40 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 11/88 (12.5) vs. 36/339 (10.3) Bacterial 11/88 (12.5) vs. 36/339 (10.3) Overall 18/150 (12) vs. 36/339 (10.3) Bacterial 18/150 (12) vs. 36/339 (10.3) |

| Quartuccio et al. 41 | NA | 0/15 (0) vs. 0/69 (0) | 3/27 (11.1) vs. 0/0 (0) | 1/15 (6.7) vs. 0/69 (0) |

Overall 18/111 (16.2) vs. 0 (0) Bacterial 18/111 (16.2) vs. 0 (0) |

| Martínez‐Sanz et al. 42 | 19 [NA] vs. 10 [NA] a | 50/260 (19) vs. 32/969 (3) | NA | 61/260 (23) vs. 120/969 (12) | NA |

| Guaraldi et al. 43 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 24/132 (14.4) vs. 14/222 (6) Bacterial 12/132 (9.1) vs. 11/222 (4.6) Fungal 7/132 (5.3) vs. 3/222 (1.4) |

| Campochiaro et al. 44 | 13.5 [10–16.7] vs. 14 [12–15.5] | 4/32 (13) vs. 2/33 (6) | NA | 5/32 (16) vs. 11/33 (33) |

Overall 5/32 (16.1) vs. 4/33 (12) Bacterial 4/32 (13) vs. 4/33 (12) Fungal 1/32 (3.1) vs. 0/33 (0) |

| Colaneri et al. 45 | 2 [6] vs. 14 [4] | 3/21 (14.3) vs. 12/91 (13.2) | NA | 5/21 (23.8) vs. 19/91 (20.9) | Overall 0/21 (0) vs. 0/91 (0) |

| Price et al. 46 | 12 [8–22] vs. NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 4/153 (2.6) vs. NA Bacterial 4/153 (2.6) vs. NA |

| Maeda et al. 47 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 3/23 (13) vs. 2/201 (1.1) Fungal 3/23 (13) vs. 2/201 (1.1) |

| Capra et al. 48 | 12.5 [4–18] vs. 8 [7–15] | NA | NA | NA | Overall 0/62 (0) vs. NA |

| Rossotti et al. 49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 24/74 (32.4) vs. NA |

| Eimer et al. 50 | 20 [17–30] vs. 30 [30–30] | NA | 5/22 (22.7) vs. 7/22 (31.8) | NA |

Overall 4/22 (18.2) vs.6/22 (27.3) Bacterial 4/22 (18.2) vs. 6/22 (27.3) |

| Kimmig et al. 51 | NA | NA | 19/54 (35.2) vs. 11/57 (19.3) | NA |

Overall 27/48 (56.3) vs. 18/63 (28.6) Bacterial 26/54 (48.1) vs. 16/57 (28.1) Fungal 3/54 (5.6) vs. 0/57 (0) |

| Tsai et al. 52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kewan et al. 53 | 11 [6–22.3] vs. 7 [5–13.5] | NA | NA | NA | Overall 5/28 (18) vs. 5/51 (22) |

| Patel K et al. 54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rojas‐Marte et al. 55 | 14.5 (8.8) vs. 16.5 (10.8) | NA | 41/61 (67.2) vs. 45/60 (75) a | 2/33(6.1) vs. 9/34 (26.5) a |

Overall 16/61 (16.7) vs. 26/60 (26.8) Bacterial 12/61 (12.5) vs. 23/60 (23.7) Fungal 4/61 (4.2) vs. 3/60 (3.1) |

| Roumier et al. 56 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 11/49 (22) vs. 18/47 (38) Bacterial 11/49 (22) vs. 18/47 (38) |

| Rossi et al. 57 | NA | NA | NA | 36/106 (34) vs. 80/140 (57.1) | NA |

| Potere et al. 58 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 1/40 (2.5) vs. 3/40 (7.5) Bacterial 1/40 (2.5) vs. 3/40 (7.5) |

| Klopfenstein et al. 59 | 17 (10.1) vs. 15.2 (12) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Canziani et al. 60 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 20/64 (31) vs. 25/64 (39) |

| Biran et al. 61 | NA | NA | 102/210 (49) vs. 256/420 (61) | NA |

Overall 36/210 (17) vs. 54/420 (13) Bacterial 36/210 (17) vs. 54/420 (13) |

| Albertini et al. 62 | 15 (NA) vs. 13 (NA) | NA | NA | NA | Overall 0 vs. 0 |

| Galván‐Román et al. 63 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 3/58 (5.2) vs. 7/88 (8) Bacterial 3/58 (5.2) vs. 7/88 (8) |

| Moreno‐Pérez et al. 64 | 16 [11–23] vs. 5 [7–9] | 42/77 (54.5) vs. 6/159 (3.8) | NA | 10/77 (12.9) vs. 3/159 (1.9) | NA |

| Zheng et al. 65 | 27.5 (6–62) vs.16.4 (4–46) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Moiseev et al. 66 | NA | NA |

27/83 (32.5) vs. 12/54 (22.2) 47/76 (61.8) vs. 73/115 (63.5) |

NA | NA |

| Roomi et al. 67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Holt et al. 68 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Menzella et al. 69 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 2/41 (5) vs. 0/38 Bacterial 2/41 (5) vs. 0/38 |

| Gupta et al. 70 | NA | NA | 125/419 (28.9) vs. 1419/3492 (40.6) | NA |

Overall 140/419 (32.3) vs. 1085/3492 (31.1) Bacterial 140/419 (32.3) vs. 1085/3492 (31.1) |

| Masiá et al. 71 | 13 [11–20.8] vs. 9 [6–13] | 9/76 (11.8) vs. 8/62 (12.9) | NA | 2/76 (2.6) vs. 8/62 (12.9) | NA |

| Gokhale et al. 72 | 14 [9–25.5] vs. 6 [13–14] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Widysanto et al. 73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tian et al. 74 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ruiz‐Antorán 75 | NA | NA | NA | 45/268 (16.8) vs. 75/238 (31.5) | Overall 1/268 (0.4) vs. NA |

| Fisher et al. 76 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 13/45 (28.9) vs. 18/70 (25.7) |

| Castelnovo et al. 77 | 20 (NA) vs. NA | 5/50 (10) vs. NA | NA | 6/50 (12) vs. 21/62 (33.9) | NA |

| Buzón‐Martín et al. 78 | 17 (10–27) vs. 10 (10–17) | NA | NA | NA | Overall 21/163 (12.9) vs. 28/211 (13.3) |

| Cavalli et al. a , 79 | NA | NA | NA | 45/55 (82) vs. 187/275 (68) | NA |

| Chachar et al. 80 | 5 [1.5–8.5] vs. 9 [4–14] | NA | NA | 6/33 (18.2) vs 4/60 (6.7) | NA |

| Gokhale et al. 81 | NA | NA | NA | 79 (52.3) vs. 74 (62.7) | NA |

| Huang et al. 82 | NA | NA | 8 (14.5) vs. 15 (36.6) | NA | Overall 17/55 (31) vs. 7/41 (17) |

| López‐Medrano et al. 83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 3/80 (3.8) vs. 11/181 (6.1) |

| Mehta et al. 84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 10/33 (30) vs. 17/74 (23) |

| Van den Eynde et al. 85 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ip et al. 86 | NA | NA | 61/134 vs. 231/413 | NA | Overall 18/134 (13) vs. 44/413 (11) |

| Hill et al. 87 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 4 (9) vs. 2 (4) |

| Lewis et al. 88 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 171 (34.4) vs. 53 (10.7) |

| Petit et al. 89 | 15.5 (NA) vs. 10.3 (NA) | NA | NA | NA |

Overall 12/74 vs. 3/74 Fungal 3/74 vs. 1/74 |

| Somers et al. 90 | 20.5 [13.8–35.8] | NA | 14 (18) vs. 27 (36) | NA | Overall 42/78(54) vs. 20/76(26) |

| Mikulska et al. 91 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Okoh et al. 92 | NA | NA | NA | 2 (10) vs. 3 (8) | NA |

| Nasa et al. 93 | NA | NA | 2 (9.1) vs. 36 (57.1) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available/applicable; SD, standard deviation; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Estimate.

TABLE 4.

Trials. General data

| Author | Trial name | Country | Type of study | N TCZ/Control | Study period | Enrollment criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone et al. 94 | BACC BAY | US | Double‐blind RCT | 161/81 | APR 20‐JUN 15 | >38°C+ pulmonary infiltrates + O2 to maintain SpO2>92% +1 out of: CRP>50 mg/l, ferritin>500 ng/ml, D‐dimer>1000 ng/ml, LDH>250 U/l |

| Salvarani et al. 95 | RCT‐TCZ‐COVID−19 | ITA | Open‐label RCT | 60/66 | MAR 31‐JUN 11 | PaO2/FiO2 200–300 mmHg+>38°C+CRP>10 mg/dl |

| Hermine et al. 96 | CORIMUNO−19 | FR | Open‐label RCT | 64/67 | MAR 31‐APR 18 | WHO clinical progression scale score ≥5 + O2>3 l/min+no MV |

| Malekzadeh et al. 97 | ‐ | IRAN | Single‐arm open‐label | 126/0 | MAR 15‐JUN 22 | >37.8°C+>30 bpm+SpO2≤93%+ IL6x3 |

| Dastan et al. 98 | ‐ | IRAN | Single‐arm open‐label | 76/0 | NA | IL6>10 pg/ml +SpO2<90%+ICU or MV |

| Salama et al. 99 | EMPACTA | a | Double‐blind RCT | 250/127 | NA‐SEPT 30 | Pneumonia+SpO2<94% with ambient air and without MV |

| Veiga et al. 100 | TOCIBRAS | BRA | Open‐label RCT | 65/64 | MAY 8‐JUL 17 | Pneumonia+O2 to maintain SpO2>94%+less than 24 h of MV+2 out of: D‐dimer>1000 ng/ml or CRP>50 mg/l or ferrtin>300 µg/l |

| Pomponio et al. 101 | ‐ | ITA | Single‐arm open‐label | 46/0 | MAR 12‐MAR 26 | Pneumonia+O2 to maintain SpO2>93%+worsening of lung function |

| Perrone et al. 102 | TOCIVID−19 | ITA | Single‐arm open‐label | 301/0 | MAR 19‐MAR 20 | SpO2≤93%+ |

| Gordon et al. 103 | REMAP‐CAP | UK | Open‐label RCT | 353/402 | MAR 9‐NOV 19 | ICU + MV or HFNC |

| Rosas et al. 104 | COVACTA | b | Double‐blind RCT | 294/144 | APR 3‐MAY 28 | SpO2≤93% or PaO2/FiO2<300 mmHg |

| Soin et al. 105 | COVINTOC | IND | Open‐label RCT | 91/88 | MAY 30‐AUG 31 | >15 bpm + SpO2≤94% |

| Wang et al. 106 | ‐ | CHI | Open‐label RCT | 34/31 | FEB 13‐MAR 13 | Bilateral pneumonia +high IL6 |

| Horby et al. 107 | RECOVERY | UK | Open‐label RCT | 2022/2094 | APR 23‐JAN 24 2021 | SpO2<92% + CRP≥75 mg/l |

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit; IL6, interleukin 6; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MV, mechanical ventilation; NA, not applicable/available; TCZ, tocilizumab; HFNC, high‐flow nasal cannula; US, United States; ITA, Italy; FR, France; BRA, Brazil; UK, United Kingdom; IND, India; CHI, China.

Multicountry: US, BRA, Kenia (KEN), Mexico (MEX), PERU, South Africa (SAFR).

Multicountry: Canada (CAN), Denmark (DEN), FR, Germany (GER), ITA, Netherlands (NETH), SPA, UK, US.

TABLE 5.

Trials. Drugs and outcomes

| Author |

Age (years) TCZ patients Mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

Males TCZ n (%) |

Days from onset to TCZ infusion Mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

TCZ doses |

TCZ infusion 1/ ≥2 |

CS TCZ vs. controls n (%) |

Remdesivir TCZ vs. controls n (%) |

Follow‐up, days Mean (SD) or median [IQR] |

Mortality TCZ vs. controls n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone et al. 94 | 60 (37) | 96 (60) | 9 [6–13] | 8 mg/kg iv | 161/0 | 18 (11) vs. 5 (6) | 55 (33) vs. 24 (29) | 28 (NA) | 9 (5.6) vs. 3 (3.7) |

| Salvarani et al. 95 | 61.5 [51.5–73.5] | 40 (66.7) | 7 [4–11] | 8 mg/kg iv | 0/60 | 1 (1.7) vs.4 (6.3) | 0 vs. 0 | 30 (NA) | 2 (3.3) vs. 1 (1.6) |

| Hermine et al. 96 | 64 [57.1–74.3] | 44 (70) | 10 [7–13] | 400 mg−8 mg/kg iv | 36/28 | 21 (33) vs. 41 (61) | 0 vs. 1 (1.5) | 28 (NA) | 7 (11) vs. 8 (12) |

| Malekzadeh et al. 97 | 55 [20–85] | 80 (63.5) | NA | 324–486 mg sc | 126/0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 30 (23.8) |

| Dastan et al. 98 | 56 [44–61] | 27 (64) | NA | 400 mg iv | 76/0 | 0 | 0 | 28 [NA] | 7 (16.7) |

| Salama et al. 99 | 56 (14.3) | 150 (60.2) | 8 [range 0–31] | 8 mg/kg iv | 182/68 | 200(80.3) vs. 112(87.5) | 131(52.6) vs.75(58.6) | 60 [NA] | 26 (10.4) vs. 11 (8.6) |

| Veiga et al. 100 | 57.4 (15.7) | 44 (68) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | 65/0 | 45 (69) vs. 47 (73) | 0 vs. 0 | 28 [NA] | 14 (21) vs. 6 (9) |

| Pomponio et al. 101 | 67.5 (34–89) | 33 (72) | 9.5 [NA] | 8 mg/kg iv | 46/0 | 0 | 0 | 25 [NA] | 7 (15.2) |

| Perrone et al. 102 | NA | 242 (80.4) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | 137/164 | 62 (21.8) vs. NA | 1 (0.4) vs. NA | 30 [NA] | 67 (22.4) vs. NA |

| Gordon et al. 103 | 61.5 (12.5) | 261 (74) | NA | 8 mg/kg iv | NA | 50 (14.2) vs. 52 (12.9) | 107(31.4)vs.133(34.2) | 21 [NA] | 98 (28) vs.142 (36) |

| Rosas et al. 104 | 60.9 (14.6) | 205 (69.7) | 11 [range 1–49] | 8 mg/kg iv | 230/65 | 57 (19.4) vs. 41 (28.5) | NA | 28 [NA] | 58 (19.7) vs. 28 (19.4) |

| Soin et al. 105 | 56 [47–63] | 76 (84) | NA | 6 mg/kg iv | NA | 83 (91) vs. 80 (91) | 39 (43) vs. 36 (41) | 28 [NA] | 11 (12) vs. 15 (17) |

| Wang et al. 106 | 63.5 [58–71] | 18 (52.9) | 20 [9–29] | 400 mg iv | NA | 5 (14.7) vs. 2 (6.5) | NA | NA | 1 (5.9) vs. 4 (12.9) |

| Horby et al. 107 | 63.3 (13.7) | 1335 (66) | 9 [7–13] | 400–800 mg iv | NA | 1664 (82) vs. 1721 (82) | 0 vs. 0 | 28 [NA] | 596 (29) vs. 694 (33) |

Abbreviations: CS, corticosteroids; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable/available; SD, standard deviation; TCZ, tocilizumab.

TABLE 6.

Secondary outcomes of trials: length of stay, ICU admission, ICU vs. ward mortality, and infections

| Author | Length of stay TCZ vs. controls days, mean (SD or range) or median [IQR] |

ICU admission TCZ vs. controls n/N (%) |

TCZ prescribed at ICU mortality TCZ vs. controls n/N (%) |

TCZ prescribed at the ward mortality TCZ vs. controls n/N (%) |

Infections TCZ vs. controls n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone et al. 94 | NA | NA | NA | 9/161 (5.6) vs. 3/81 (3.7) | Overall 13/161 (8.1) vs. 14/81 (17.1) |

| Salvarani et al. 95 | NA | 6/60 (10) vs. 5/63 (7.9) | NA | 2/60 (3.3) vs. 1/63 (1.6) | Overall 5/161 (4.1) vs. 1/81 (1.7) |

| Hermine et al. 96 | NA | 11/60 (18) vs. 22/64 (34) | NA | NA |

Overall 2/63 (3.2) vs. 13/67 (19.4) Bacterial 2/63 (3.2) vs. 11/67 (16.4) Fungal 0/63 (0) vs. 2/67 (3) |

| Malekzadeh et al. 97 | 8 [5–12] | NA | 24/40 (60) | 6/86 (6.98) | NA |

| Dastan et al. 98 | 15 [NA] | NA | 6/22 (27) | 1/20 (5) | NA |

| Salama et al. 99 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 25/250 (10) vs.169/127 (12.6) |

| Veiga et al. 100 | 11.3 (8) vs. 14.7 (8.2) | NA | NA | NA | Overall 10/65 (15) vs. 10/64 (16) |

| Pomponio et al. 101 | NA | 11/46 (23.9) | NA | 7/46 (15.2) | Overall 6/46 (13) vs. NA |

| Perrone et al. 102 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gordon et al. 103 | NA | NA | 98/350 (28) vs.142/397 (36) | NA | NA |

| Rosas et al. 104 | 20 [NA] vs. 28 [NA] | NA | NA | NA | Overall 113/295 (38.3) vs. 58/143 (40.6) |

| Soin et al. 105 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall 5/91 (5) vs. 5/88 (6) |

| Wang et al. 106 | 26 [17–27] vs. 24 [15–28] | NA | NA | 32/34 (94.1) vs. 27/31 (87.1) | Overall 0 vs. 0 |

| Horby et al. 107 | 20 [NA] vs. 28 [NA] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available/applicable; SD, standard deviation; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Concomitantly to TCZ use, additional treatment with corticosteroids was given in 4122/7389 patients in the TCZ group (55.8%) versus 5161/12,547 (41.1%) in the control group (p < 0.001). Comparing both groups, remdesivir was used in 394/6471 (6.1%) patients treated with TCZ versus 327/11,326 (2.9%) in the control group (p < 0.001). Finally, TCZ was administered at a median of 10.2 [IQR 8–11] days after the onset of COVID‐19 symptoms, in those studies in which these data were provided.

3.2. In‐hospital mortality

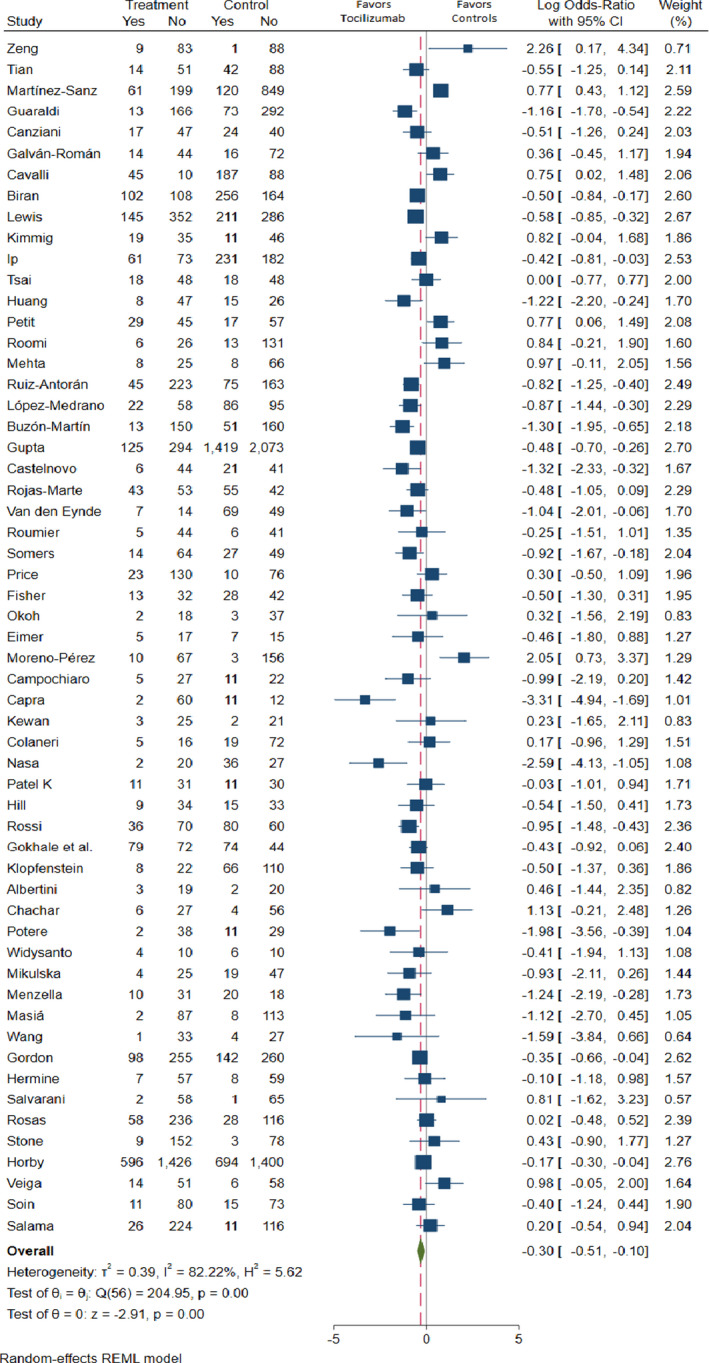

After applying the random‐effects model, hospital‐wide (including ICUs) pooled mortality OR of patients with COVID‐19 treated with TCZ was 0.73 (95%CI = 0.56–0.93) with a high, significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 82%) (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Across designs, the pooled overall number needed to treat (NNT) to avoid one death was 16.9 (95%CI 10.9 to 40.0): 14.1 (95%CI 9.1 to 40.0) in retrospective cohorts, −3.8 (95%CI −20.0 to 7.69) in prospective cohorts, and 58.8 (95%CI −25.6 to 90.9) in RCTs. The pooled mortality OR without outliers of patients with COVID‐19 treated with TCZ was 0.67 (95% CI 0.55–0.83) (I 2 = 76%) (p < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis excluding these studies showed an 8% significant increase in the effect size and 5% reduction in heterogeneity Egger's test did not find significant publication bias (beta 1 = 0.58, p = 0.55). The Abbé plot of variance‐weighted values showed four studies as outliers in effect size. 42 , 48 , 64 , 65 The Forest plot in the retrospective studies by country is shown in the Supporting Information S4. It was found that the country of the study was a significant cause of heterogeneity, but sensitivity analyses excluding country by country did not show significant impact on pooled ORs, with nonsignificant changes after excluding individually country of study in ORs from +1% (excluding IDN, PAK, SWE, and the US) to −3% (excluding SPA). Further analysis by country of study did not show any impact on results; thus, it was not considered a potential confounder at the aggregated level of analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of mortality

The pooled mortality OR without outliers of patients with COVID‐19 treated with TCZ was 0.67 (95% CI 0.55–0.83) (I 2 = 76%) (p < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis excluding these studies showed an 8% significant increase in the effect size and 5% reduction in heterogeneity (Supporting Information S5). Meta‐regression results indicate the study variables explaining heterogeneity (Supporting Information S6). The country of study added significant heterogeneity. As for continuous variable, a higher number of TCZ patients in the ICU increased estimated TCZ effects. A higher mortality rate in control groups and the percentage of patients with more than one TCZ infusion decreased the effects. Multivariable meta‐regression on control mortality rates and the percentage of patients undergoing more than one TCZ infusion (proxy of perceived severity) decrease heterogeneity down to 58% (acceptable). This result indicates that patient selection and severity (using the percentage of patients with more than one TCZ infusion as a perceived severity indicator) explain 26% interstudy heterogeneity. The funnel plot did not show signs of asymmetry indicating publication bias (Supporting Information S7).

3.3. In‐hospital mortality in the TCZ group receiving additional corticosteroids

After applying the random‐effects model, the pooled OR of hospital‐wide mortality (including ICUs) of COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ plus CS was 0.67 (95% CI = 0.54–0.84).

3.4. In‐hospital mortality in the TCZ group receiving early vs. late TCZ administration

After applying the random‐effects model, the pooled mortality OR for COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ was 0.71 (95% CI = 0.35–1.42) in patients with early administration (≤10 days from symptom onset) versus 0.83 (95% CI = 0.48–1.45) in those with late administration (>10 days from symptom onset).

3.5. In‐hospital mortality in the ward vs. ICU

After applying the random‐effects model, the pooled mortality OR for COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ in the conventional ward was 1.25 (95% CI = 0.74–2.18) versus 0.66 (95% CI = 0.59–0.76) in the ICU (Supporting Information S8 and S9).

3.6. Risk of ICU admission

After applying the random‐effects model, the pooled risk of the ICU admission OR for COVID‐19 patients in whom TCZ was administered in the conventional ward was 3.70 (95% CI = 1.25–10.80).

3.7. Follow‐up and safety

The median follow‐up of the overall cohort was 28 [range 7–83] days. After applying the random‐effects model, the pooled risk of secondary infections OR for COVID‐19 patients treated with TCZ was 1.04 (95% CI = 0.72–1.52) (Supporting Information S10).

4. DISCUSSION

To date, 14 published SRMAs have assessed the beneficial and harmful effects of TCZ in COVID‐19. 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 These previously published SRMAs differed widely in the number and type of studies included—preprints, controlled and uncontrolled observational studies, or RCTs. Consequently, results have also been controversial. Some reported SRMAs showed a benefit of TCZ use in terms of preventing mortality 108 , 109 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 116 , 119 , 120 , clinical improvement 121 , or progression to mechanical ventilation (MV) and ICU admission. 109 , 111 , 112 , 117 , 118 However, other SRMAs did not show a clear beneficial effect of TCZ use. 110 , 115 , 116 In general, positive effects of TCZ in COVID‐19 have been seen in SRMAs that include real‐world observational data.

The present study is the most updated SRMA summarizing current published evidence from controlled observational studies and RCTs on the effect of TCZ in different subgroups of patients with COVID‐19 requiring hospitalization. Furthermore, our work is the first SRMA as such showing a beneficial effect of TCZ in severe COVID‐19 in improving survival across controlled observational studies and RCTs. Country of study did not cause significant heterogeneity so that ecological results concerning health systems are not likely to cause differences in results. Rather, heterogeneity seems related to inclusion criteria and specific care practices in each study. Unfortunately, the definition of severe COVID‐19 is very heterogeneous in the different studies included. In general, the definition of severe COVID‐19 included a respiratory status criterion (i.e., acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or SpO2<93%) and some analytical inflammatory parameter. In addition, there are studies carried out in ICU patients, others in the hospital ward, and others (the most frequent) in a mixture of ICU and ward patients. These differences in the NNT between observational studies and RCTs are basically explained by the different severity of the patients included in the control group. The RCTs included patients with much lower disease severity and, above all, patients who were much less inflamed, which therefore may dilute a possible beneficial effect of TCZ. A good way to realize this fact is to look at the mortality ratio of the control group or the inflammatory parameters published in the RCTs.

Looking specifically at the present results reported from the high‐quality controlled observational studies and RCTs included in the present SRMA, it seems clear that TCZ has a beneficial role in preventing mortality and improving other clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. However, a crucial point was to determine if included patients received TCZ not only because of their need for oxygenation but also due to the presence of a hyperinflammatory syndrome. TCZ is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin‐6 receptor (IL‐6R), which plays an important role in the host immune response implicated in the pathogenesis of many diseases, including severe COVID‐19. Accordingly, TCZ should not be used to treat COVID‐19 patients with hypoxemia not due to the lung injury and systemic hyperinflammation shown in the advanced stages of the disease. In this respect, the present SRMA showed a major benefit of TCZ when it was administered early in those highly inflamed patients. Therefore, TCZ is not expected to confer benefit in patients with low inflammatory states.

A common main limitation of real‐world observational studies was the mixture of patients included, either admitted to the conventional ward or ICU, and most patients receiving TCZ with concomitant corticosteroids. Consequently, it was not possible to assess the separate effect of corticosteroids from that of TCZ, as well as the efficacy and safety of TCZ in patients with different levels of severity, treated in hospital wards or in ICUs. Moreover, the time frame of published studies is mostly constricted to the initial pandemic period (all studies were initiated by the end of January and ended as of May 2020, and 90% had a duration of 90 days or less). Thus, the literature reviewed in our SRMA reflects the impact of treatment in population care practices during the initial phases of the COVID‐19 pandemic. The effect of current care practices and, of course, the impact of the vaccines is not reflected in the studies.

Although RCTs are studies that allow control of potential bias and confounding factors, not all trials published to date and included in this SRMA met the criteria for an appropriate indication of TCZ use in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. The RCTs evaluated in this SRMA relied heavily on the oxygenation/ventilation status of patients but little on the degree of inflammation of included patients. TCZ has generally been prescribed based on inflammatory parameters with good results in real life and not so much based on respiratory status as the criteria for inclusion of patients treated with TCZ in many RCTs. In this respect, the potential beneficial effect of TCZ was likely diluted in those trials in which an important proportion of non‐ or low‐inflamed population were included. Unfortunately, several of the RCTs carried out to date assessed the effect of TCZ use in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients with low laboratory values of inflammatory parameters such as ferritin, C‐reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D‐dimer, and lymphopenia. We believe that a good classification strategy to better define severe COVID‐19 into different grades of inflammation based on these parameters has been published recently by our group. 132 Patients at high risk of severe COVID‐19 according to analytical inflammatory parameters would benefit most from the use of TCZ. Furthermore, in‐hospital mortality rates in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 have been reported to be around 20% or higher. In this regard, it should be remembered that the placebo arm of the RECOVERY trial (dexamethasone vs. placebo) had a mortality rate of 25%. 2 However, COVID‐19 patients included in some trials, such as the one by Stone et al. 94 , showed a very low mortality rate of 4.9% in the placebo group, which was more representative of an outpatient population not requiring immunosuppressive treatments, rather than that of patients who met hospitalization criteria used worldwide.

In an ideal scenario, it would be necessary to perform subanalyses to analyze the true efficacy and safety of TCZ at different stages of the disease and in different settings. For example, the potential beneficial or harmful effect of TCZ may not be the same in studies performed in inflamed versus noninflamed patients, in patients receiving TCZ with corticosteroids compared with TCZ alone, in patients treated in conventional wards compared with ICUs, in developed versus developing countries, or at the first wave of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 compared with the current days more than 1 year after the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

In general, the patients included in the different studies included in this SRMA received a single dose of TCZ. However, some patients received two doses and very rarely three doses. It is not possible from the data we have to analyze whether the number of doses influences in‐hospital mortality. Furthermore, it should be taken into account that those patients who received more than one dose were patients who were somehow interpreted by their physicians to be more severely ill. Thus, it is possible that paradoxically, we found that the more doses of TCZ, the greater the mortality risk.

The low use of remdesivir in the included studies is striking. Possibly, this is due to the poor availability of the drug at many times during the pandemic and in certain countries. At least it helps us in the present SRMA as the use of remdesivir does not add a confounding factor to the results.

From the subanalysis performed taking into account the day of TCZ administration, it is intuited that early administration before Day 10 of symptoms could be beneficial. It is only an approximation based on the mean of the day of TCZ administration in the study and, therefore, includes patients in a wide range on the day of administration. On the other hand, it has been said that the escalation of inflammation occurs in the second week from the onset of symptoms. This is more of a philosophical model than a real one based on scientific evidence. The reality is that there are patients who become inflamed in the second week, whereas others present very early inflammation.

The higher OR found in our study of admission to the ICU in patients with COVID‐19 who received TCZ should not lead us to think that by receiving this drug, more patients will require admission to the ICU. These data clearly indicate that patients with greater disease severity have more easily received TCZ. For this reason, in an RCT, it is so important to define the disease severity of the patient when receiving TCZ or the corresponding SOC. We believe that this disease severity should be evaluated not only with the respiratory status but also with the degree of analytical inflammation of the patient.

In the present SRMA, we found a greater benefit with the use of TCZ versus SOC in ICU patients compared with ward patients. The more inflamed the patients are, the more these differences will be seen. Patients admitted to the ICU for COVID‐19 generally have a high degree of inflammation, and therefore, the beneficial effect of TCZ becomes more evident. However, in conventional ward patients who are often not inflamed or have mild degrees of inflammation, if these inflamed ward patients are not well‐selected, the possible beneficial effect of TCZ is diluted.

Regarding the safety of TCZ, we can say that from the data analyzed in our SRMA, it seems to be a safe drug in terms of the rate of secondary infections. The current meta‐analysis did not find a significantly higher risk for secondary infections in patients with COVID‐19 treated with TCZ. As TCZ has been administered to more severe patients with COVID‐19, many of them in the ICU or requiring ICU admission during the follow‐up, a higher incidence of infections is to be expected in this subpopulation. The causes are known and multifactorial, especially related to a greater number of invasive procedures, including MV, in more severely ill patients.

In this SRMA, we tried to approximate these subanalyses in accordance with the data provided in the included studies. Despite limitations, we believe that the scientific community is getting closer to the truth regarding the effect of TCZ use in COVID‐19 and will get even closer in the future as patient selection in these studies improves, particularly if patient selection is increasingly based on inflammatory severity criteria. 132 The sooner we define this subpopulation of patients who meet severe inflammatory criteria, the sooner we will probably see the real effects of TCZ therapy in treating COVID‐19. Our opinion, based on data obtained from this SRMA, is that TCZ would be indicated early, in combination with CS, in COVID‐19 patients with lung injury and systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome requiring hospitalization. This inflammation should be based on ferritin, CRP, LDH, D‐dimer, and the presence of lymphopenia. Respiratory status or admission to the ICU is still only surrogates for disease severity or inflammation status of patients with COVID‐19.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Jordi Rello has received consultancy honoraria from Roche. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

File S1

File S2

File S3

File S4

File S5

File S6

File S7

File S8

File S9

File S10

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support.

Rubio‐Rivas M, Forero CG, Mora‐Luján JM, et al. Beneficial and harmful outcomes of tocilizumab in severe COVID‐19: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2021;41:884–906. doi: 10.1002/phar.2627

Rubio‐Rivas and Forero contributed equally as first authors.

Rello and Corbella contributed equally as last authors.

Funding information

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article

REFERENCES

- 1. Kenny G, Mallon PWG. Tocilizumab for the treatment of non‐critical COVID‐19 pneumonia: an overview of the rationale and clinical evidence to date. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021. 10.1080/17512433.2021.1949286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693‐704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID‐19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:10970‐10975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, et al. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID‐19: a single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:814‐818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antony SJ, Davis MA, Davis MG, et al. Early use of tocilizumab in the prevention of adult respiratory failure in SARS ‐ CoV ‐ 2 infections and the utilization of interleukin ‐ 6 levels in the management. Idcases. 2020;21:e00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quartuccio L, Sonaglia A, Pecori D, et al. Higher levels of IL‐6 early after tocilizumab distinguish survivors from non‐survivors in COVID‐19 pneumonia: a possible indication for deeper targeting IL‐6. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.26149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Toniati P, Piva S, Cattalini M, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID‐19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: a single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19: 102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alattar R, Ibrahim TBH, Shaar SH, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sciascia S, Aprà F, Baffa A, et al. Pilot prospective open, single‐arm multicentre study on off‐label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID‐19. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:529‐532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison AR, Johnson JM, Griebe KM, et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of survival in adults with coronavirus disease 2019 receiving tocilizumab. J Autoimmun. 2020;114: 102512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morena V, Milazzo L, Oreni L, et al. Off‐label use of tocilizumab for the treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Milan, Italy. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:36‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marfella R, Paolisso P, Sardu C, et al. Negative impact of hyperglycaemia on tocilizumab therapy in Covid‐19 patients. Diabetes Metab. 2020. S1262‐3636(20)30082‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jordan SC, Zakowski P, Tran HP, et al. Compassionate use of tocilizumab for treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:3168–3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borku Uysal B, Ikitimur H, Yavuzer S, et al. Tocilizumab challenge: a series of cytokine storm therapy experiences in hospitalized COVID‐19 pneumonia patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2648–2656. 10.1002/jmv.26111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Issa N, Dumery M, Guisset O, et al. Feasibility of tocilizumab in ICU patients with COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020;93(1):46–47. 10.1002/jmv.26110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campins L, Boixeda R, Perez‐Cordon L, et al. Early tocilizumab treatment could improve survival among COVID‐19 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanz Herrero F, Puchades Gimeno F, Ortega García P, et al. Methylprednisolone added to tocilizumab reduces mortality in SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia: an observational study. J Intern Med. 2021;289:259–263. 10.1111/joim.13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knorr JP, Colomy V, Mauriello CM, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID‐19: A single‐center observational analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2813–2820. 10.1002/jmv.26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lohse A, Klopfenstein T, Balblanc JC, et al. Predictive factors of mortality in patients treated with tocilizumab for acute respiratory distress syndrome related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Microbes Infect. 2020;22:500‐503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Conrozier T, Lohse A, Balblanc JC, et al. Biomarker variation in patients successfully treated with tocilizumab for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): results of a multidisciplinary collaboration. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:742‐747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petrak R, Skorodin N, Van Hise N, et al. Tocilizumab as a therapeutic agent for critically ill patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2. Clin Transl Sci. 2020. 10.1111/cts.12894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hernández‐Mora MG, Cabello A, Prieto Perez L, et al. Compassionate use of tocilizumab in severe SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;102:303‐309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiménez‐Brítez G, Ruiz P, Soler X. Tocilizumab plus glucocorticoids in severe and critically COVID‐19 patients. A single center experience. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:410‐411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sinha P, Mostaghim A, Bielick CG, et al. Early administration of interleukin‐6 inhibitors for patients with severe COVID‐19 disease is associated with decreased intubation, reduced mortality, and increased discharge. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:28‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patel A, Shah K, Dharsandiya M, et al. Safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2020;38:117‐123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Formina DS, Lysenko MA, Beloglazova IP, et al. Temporal clinical and laboratory response to interleukin‐6 receptor blockade with Tocilizumab in 89 hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia. Pathogens and Immunity. 2020;5:327‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rubio‐Rivas M, Ronda M, Padulles A, et al. Beneficial effect of corticosteroids in preventing mortality in patients receiving tocilizumab to treat severe COVID‐19 illness. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:290‐297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sirimaturos M, Gotur DB, Patel SJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following tocilizumab administration in mechanically ventilated coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Crit Care Expl. 2020;2:e0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Cáceres C, Martínez R, Bachiller P, Marín L, García JM. The effect of tocilizumab on cytokine release syndrome in COVID‐19 patients. Pharmacol Rep. 2020; 72:1529–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Langer‐Gould A, Smith JB, Gonzales EG, et al. Early identification of COVID‐19 cytokine storm and treatment with anakinra or tocilizumab. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:291‐297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Di Nisio M, Potere N, Candeloro M, et al. Interleukin‐6 receptor blockade with subcutaneous tocilizumab improves coagulation activity in patients with COVID‐19. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;83:34‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mady A, Aletreby W, Abdulrahman B, et al. Tocilizumab in the treatment of rapidly evolving COVID‐19 pneumonia and multifaceted critical illness: a retrospective case series. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;60:417‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zain Mushtaq M, Bin Zafar Mahmood S, Jamil B, Aziz A, Ali SA. Outcome of COVID‐19 patients with use of Tocilizumab: a single center experience. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meleveedu KS, Miskovsky J, Meharg J, et al. Tocilizumab for severe COVID‐19 related illness ‐ a community academic medical center experience. Cytokine X. 2020;2:100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mo Y, Adarkwah O, Zeibeq J, Pinelis E, Orsini J, Gasperino J. Treatment with tocilizumab for patients with Covid‐19 infections: a case‐series study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;61:406‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaminski MA, Sunny S, Balabayova K, et al. Tocilizumab therapy for COVID‐19: a comparison of subcutaneous and intravenous therapies. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:59‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corominas H, Castellví I, Pomar V, et al. Effectiveness and safety of intravenous tocilizumab to treat COVID‐19‐associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: covizumab‐6 observational cohort. Clin Immunol. 2021;223:108631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keske S, Tekin S, Sait B, et al. Appropriate use of tocilizumab in COVID‐19 infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:338‐343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guillén L, Padilla S, Fernández M, et al. Preemptive interleukin‐6 blockade in patients with COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rodríguez‐Baño J, Pachón J, Carratalà J, et al. Treatment with tocilizumab or corticosteroids for COVID‐19 patients with hyperinflammatory state: a multicentre cohort study (SAM‐COVID‐19). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:244‐252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Quartuccio L, Sonaglia A, Mcgonagle D, et al. Profiling COVID‐19 pneumonia progressing into the cytokine storm syndrome: Results from a single Italian Centre study on tocilizumab versus standard of care. J Clin Virol. 2020;129:104444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martínez‐Sanz J, Muriel A, Ron R, et al. Effects of tocilizumab on mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: a multicentre cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:238‐243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guaraldi G, Meschiari M, Cozzi‐lepri A, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID‐19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;9913:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Campochiaro C, Della‐Torre E, Cavalli G, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in severe COVID‐19 patients: a single‐center retrospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:43‐49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Colaneri M, Bogliolo L, Valsecchi P, et al. COVID IRCCS San Matteo Pavia Task Force. Tocilizumab for treatment of severe COVID‐19 patients: preliminary results from SMAtteo COvid19 REgistry (SMACORE). Microorganisms. 2020;8:695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Price CC, Altice FL, Shyr Y, et al. Tocilizumab treatment for cytokine release syndrome in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients: survival and clinical outcomes. Chest. 2020;158(4):1397‐1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maeda T, Obata R, Rizk D, et al. The association of interleukin‐6 value, interleukin inhibitors and outcomes of patients with COVID‐19 in New York City. J Med Virol. 2021;93:463‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Capra R, De Rossi N, Mattioli F, et al. Impact of low dose tocilizumab on mortality rate in patients with COVID‐19 related pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:31‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rossotti R, Travi G, Ughi N, et al. Safety and efficacy of anti‐il6‐receptor tocilizumab use in severe and critical patients affected by coronavirus disease 2019: a comparative analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e11‐e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eimer J, Vesterbacka J, Svensson AK, et al. Tocilizumab shortens time on mechanical ventilation and length of hospital stay in patients with severe COVID‐19: a retrospective cohort study. J Int Med. 2021;289:434‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kimmig LM, Wu D, Gold M, et al. IL6 inhibition in critically ill COVID‐19 patients is associated with increased secondaryInfections. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:583897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsai A, Diawara O, Nahass RG, et al. Impact of tocilizumab administration on mortality in severe COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kewan T, Covut F, Al‐Jaghbeer MJ, et al. Tocilizumab for treatment of patients with severe COVID19: a retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Patel K, Gooley TA, Bailey N, et al. Use of the IL‐6R antagonist tocilizumab in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients. J Inter Med. 2021;289:430‐433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rojas‐Marte GR, Khalid M, Mukhtar O, et al. Outcomes in patients with severe COVID‐19 disease treated with tocilizumab – a case‐ controlled study. QJM. 2020;113:546‐550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Roumier M, Paule R, Vallée A, et al. Tocilizumab for severe worsening COVID‐19 pneumonia: a propensity score analysis. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(2):303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rossi B, Nguyen LS, Zimmermann P, et al. Effect of tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with severe COVID‐19 pneumonia: a case‐control cohort study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;13:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Potere N, Di Nisio M, Cibelli D, et al. Interleukin‐6 receptor blockade with subcutaneous tocilizumab in severe COVID‐19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation: a case‐control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;80:1‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Klopfenstein T, Zayet S, Lohse A, et al. Impact of tocilizumab on mortality and/or invasive mechanical ventilation requirement in a cohort of 206 COVID‐19 patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:491‐495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Canziani LM, Trovati S, Brunetta E, et al. Interleukin‐6 receptor blocking with intravenous tocilizumab in COVID‐19 severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective case‐control survival analysis of 128 patients. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Biran N, Ip A, Ahn J, et al. Tocilizumab among patients with COVID‐19 in the intensive care unit: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e603‐e612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Albertini L, Soletchnik M, Razurel A, et al. Observational study on off‐label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID‐19. Eur. J Hosp Pharm. 2021;28:22‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Galván‐Román JM, Rodríguez‐García SC, Roy‐Vallejo E, et al. IL‐6 serum levels predict severity and response to Tocilizumab in COVID‐19: an observational study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;147:72‐80.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moreno‐Pérez O, Andres M, Leon‐Ramirez JM, et al. Experience with tocilizumab in severe COVID‐19 pneumonia after 80 days of follow‐up: a retrospective cohort study. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zeng J, Xie MH, Yang J, Chao SW, Xu EL. Clinical efficacy of tocilizumab treatment in severe and critical COVID‐19 patients. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3763‐3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moiseev S, Avdeev S, Tao E, et al. Neither earlier nor late tocilizumab improved outcomes in the intensive care unit patients with COVID‐19 in a retrospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roomi S, Ullah W, Ahmed F, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab in patients with COVID‐19: single‐center retrospective chart review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]