Abstract

Background

Lockdown measures during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic determined radical changes to behavioral and social habits, that were reflected by a reduction in the transmission of respiratory pathogens and in anthropogenic atmospheric emissions.

Objective

This ecological study aims to provide a descriptive evaluation on how restrictive measures during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic impacted Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) referrals for asthma exacerbations, and their potentially associated environmental triggers in Bologna, a densely populated urban area in Northern Italy.

Methods

Files of children evaluated for acute asthma during 2015 to 2020 at the PED of Sant'Orsola University Hospital of Bologna were retrospectively reviewed. Historical daily concentration records of particulate (PM2.5, PM10) and gaseous (NO2, C6H6) air pollutants, and pollen were concurrently evaluated, including specific PM chemical tracers for traffic‐related air pollution (TRAP).

Results

In 2020, asthma‐related PED referrals decreased compared to referral rates of the previous 5 years (p < 0.01). This effect was particularly marked during the first lockdown period (March to May), when the drastic drop in PED referrals was associated with a reduction of high‐priority cases up to 85% and by 54%, on average. A concomitant reduction in the concentrations of traffic‐related air pollutants was observed in the range of 40%–60% (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

The lower rate of asthma exacerbations in childhood was in this study paralleled with reduced TRAP levels during the pandemic. Synergic interactions of the multiple consequences of lockdowns likely contributed to the reduced exacerbations, including decreased exposure to ambient pollutants and fewer respiratory infections, identified as the most important factor in the literature.

Keywords: allergens, asthma exacerbations, oxidative stress, traffic‐related air pollution

Abbreviations

- Arpae

Agency for Prevention, Environmental and Energy of Emilia‐Romagna (Italy)

- BC

black carbon (PM chemical component)

- C6H6

benzene (gaseous air pollutant)

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease‐2019

- IOP

intensive observation periods

- Lockdown‐1

the first lockdown period in Italy from March 9 to May 3 in 2020 and continued with less restrictions until the end of May

- Lockdown‐2

the second (moderate) lockdown period in Italy from October 13 to the end of 2020 and continued in 2021 with restrictive measures varying according to the local trend of infections

- NO2

nitrogen oxide (gaseous air pollutant)

- O3

ozone (gas air pollutant)

- PED

Pediatric Emergency Department

- PM

particulate matter

- PM10

particulate matter smaller than 10 microns

- PM2.5

particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus‐2

- SSOU

short‐stay clinical observation unit

- TRAP

traffic‐related air pollution

- TRAP contribution tracer

it represents f57, which is defined as the relative abundance of the mass fragment at m/z (mass‐to‐charge ratio) 57 over the total organic PM1 mass spectrum as measured by HR‐ToF‐AMS

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

Several studies reported an overall decrease in the number of Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) admissions in 2020 during lockdown periods related to social measures adopted to limit the spreading of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, including a marked reduction of asthma referrals. 1 , 2 This led to a growing interest in determining to what extent these lifestyle changes—such as school closures, stay‐at‐home orders, and working from home in combination with protective measures, including social distancing, wearing face masks, and washing hands frequently—might have influenced asthma triggers. 3 , 4 , 5

Asthma is a multifactorial airways disease: in predisposed people, exposure to respiratory infections, air pollution, and allergens may trigger asthma exacerbations. 6 , 7 Infections are the main triggers of acute bronchospasm in children of any age, especially in the preschoolers. 8 , 9 Sensitization to environmental allergens, such as pollen, is reported as a further important risk factor for the development of asthma exacerbations. 10

Regarding the role of air pollution, most studies reported how particulate matter (PM) smaller than 2.5 and 10 microns (PM2.5, PM10) and the coemitted gaseous pollutants (NO, NO2, O3) can induce airway inflammation, hyper‐responsiveness, and oxidative injury to the airways, which can lead to asthma. 11 However, even if the international air quality standards for atmospheric PM are based on total mass concentrations, the World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges that not every PM chemical component is equally important in causing airways disease. 12 Research on this issue is mostly focused on traffic‐related air pollution (TRAP) and has provided evidence of the links between adverse health effects and PM chemical composition. 11 , 13 , 14 Urban anthropogenic PM presents a threefold higher oxidative potential per unit of PM mass concentration than rural PM. 15

In this observational retrospective cross‐sectional study, we aimed to identify how asthma‐related referrals in children were affected by the restrictive measures during the entire 2020, in relation to the main features of potentially associated environmental triggers, that is, air pollution and pollen. The selected urban area of Bologna, in Northern Italy, represents an important population basin of about 400,000 inhabitants and can be considered an ideal setting for this study as it is one of the areas more dramatically hit by the pandemic, and also well‐known for a high prevalence of respiratory disease and for being one of the main air quality European hotspot, characterized by PM levels well above the limit set by the European Air Quality Directive and by the WHO.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

Files of children evaluated for “acute asthma,” “bronchospasm,” or “wheezing bronchitis” from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020, in the PED of Sant'Orsola University Hospital of Bologna were retrospectively reviewed. Our center is an urban, academic, tertiary care Pediatric Emergency Unit, consisting of a PED with approximately 23,000 visits per year, a short‐stay observation unit (SSOU), and a ward. For the purpose of this study, the triage acuity was divided into low‐priority (white and green) and high‐priority (yellow and red) codes. Triage acuity is defined by a four‐grade color scale according to local and national protocols, which adhere to global triage guidelines. 16 A red code means that the condition is life‐threatening and requires immediate evaluation: patients with critical vital signs, unconscious, respiratory arrest, gasping, severe pallor, or cyanosis at rest. A yellow code requires rapid medical evaluation and includes patients with altered vital signs, respiratory distress, pallor or cyanosis in crying, signs of acute asthma in a patient with a history of severe chronic disease, agitated or ill patients. A green code indicates patients with normal vital signs but relevant, acute‐onset symptoms (such as cough, wheezing, etc.). A white code indicates patients with reported cough or respiratory distress, with normal vital signs and without asthma signs or symptoms in triage. 16

The outcomes (discharge, admission to the SSOU or to the ward) were also considered.

2.2. Air pollution

Daily ground level mass concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 and gaseous pollutants (NO2, C6H6), as routinely measured by the air quality monitoring program of the Agency for Prevention, Environmental and Energy (Arpae) network, are considered. Based on the criteria defined by the European Environment Agency, a monitoring station gives air quality data that are representative of a certain area around the station. The area, in which the concentration does not differ from the concentration measured at the station by more than a specified amount, can be called the area of representativeness of the station. A determination of the area of representativeness is of value when monitoring data are to be used to calculate the exposure of the population (or materials, or ecosystems). Those criteria are the distance of the station from large pollution sources. For the purpose of the present study, we, therefore, chose two urban background sites, representative of population exposure at the urban scale of the City of Bologna, approximately the same one intercepted by users of Sant'Orsola University Hospital of Bologna; and a traffic site, which is useful to better highlight changes in emission rates of local traffic‐related sources.

Unlike PM properties, which have a direct impact on asthma exacerbations, NO2 and C6H6 are considered as they generally mimic specific anthropogenic sources (e.g., fossil fuel combustion). The considered measurements cover the time period from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020, and were recorded at an urban background and urban traffic sites.

Two independent additional parameters are used as ancillary data as they permit to highlight specific physic‐chemical features of PM composition, tracing the contribution of combustion PM sources and TRAP, associated with asthma disease in other studies. 13 , 14

The first one is f57, deriving from data analysis of the mass spectra of nonrefractory submicron particles and representing the relative abundance of the mass fragment at m/z 57 (mass‐to‐charge ratio) over the total organic PM1 particles (PM less than 1 micron: fine and ultrafine particles) mass spectrum. f57 is commonly used as a spectral tracer for the contribution of PM emitted from fossil fuel combustion and it is mostly attributed to traffic‐related sources in the urban environment. 17 , 18 For this reason, it is indicated from hereafter as the TRAP contribution tracer. The data used were obtained online by a High‐Resolution Time‐of‐Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, 19 which performs the chemical composition of nonrefractory submicron particles (NR‐PM1, PM less than 1 micron: fine and ultrafine particles) and refer to measurements during the lockdown period in 2020 and from eight intensive observation periods (IOPs) carried out from November 2011 to May 2014. 20

The second additional measurement is the black carbon (BC) fraction of PM, sometimes defined as soot, a major component of PM, emitted through incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass, representing a known tracer of the main anthropogenic sources concentrated in urban areas, including heating and transport, thus also characterizing TRAP. Hourly concentrations are used as quantified from a MetOne (single‐wavelength at 880 nm) run during the time period January to May in 2019 and 2020.

Due to their expensive measurement techniques and not being suitable for routine air quality monitoring, the TRAP contribution tracer and BC data were available for shorter time periods and, therefore, it was not possible to use the same set of control time periods as the other data. Despite these limitations, these two additional measurements permitted valuable insights into the physic‐chemical properties of atmospheric PM.

2.3. Pollen data

Daily concentrations of Compositae: mugwort (Artemisia) and Urticaceae (Parietaria), tree (birch), and grass pollen were extracted from the Arpae public online repository for the time period January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020, and analyzed. These four species, characterized by different flowering periods over the year, were selected as the most relevant allergens for the study area (Central‐Southern Europe). 21

2.4. Statistical data analysis

The normality of data distributions was examined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with an interquartile range as appropriate, and categorical variables are expressed as a percentage. For the continuous variables, comparisons between two groups were made using t tests while for three or more groups with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. All the analyses were conducted in SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc.), Microsoft Windows version, and p ≤ 0.05 from two‐sided tests was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical statement

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (protocol number 177/2021/Oss/AOUBo).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Asthma

During the year 2020, the total number of PED visits for acute asthma was 349 out of a total of 14397 visits (2.4%). In the previous 5 years, the average visits for acute asthma were 585 out of an average of 22,779 total visits (2.5%). Table 1 reports the main characteristics of the study population divided into years.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the referrals data at the Pediatric Emergency Department of Sant'Orsola University Hospital of Bologna, Italy, divided by year

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 502 | 608 | 544 | 656 | 611 | 349 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 3.4 | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 3.5 ± 3.3 | 3.6 ± 3.5 | 3.5 ± 3.8 |

| Male (%) | 66.7% | 65.3% | 63.7% | 59.5% | 61.4% | 64.7% |

| Female (%) | 33.3% | 34.7% | 36.3% | 40.5% | 38.6% | 35.3% |

| White code (n; %) | 72; 14.4% | 103; 16.9% | 84; 15.4% | 130; 20% | 100; 16.4% | 48; 13.8% |

| Green code (n; %) | 228; 45.4% | 280; 46.1% | 292; 53.7% | 320; 48.8% | 300; 49.2% | 177; 50.7% |

| Yellow code (n; %) | 201; 40% | 224; 36.8% | 167; 30.7% | 203; 30.9% | 206; 33.7% | 122; 34.9% |

| Red code (n; %) | 1; 0.2% | 1; 0.2% | 1; 0.2% | 2; 0.3% | 4; 0.7% | 2; 0.6% |

| Discharge (n; %) | 424; 84.5% | 490; 80.6% | 441; 81.1% | 524; 79.9% | 490; 80.2% | 277; 79.4% |

| SSOU (n; %) | 61; 12.2% | 95; 15.6% | 78; 14.3% | 108; 16.5% | 90; 14.7% | 49; 14% |

| Admissions (n; %) | 17; 3.3% | 23; 3.8% | 25; 4.6% | 24; 3.6% | 31; 5.1% | 23; 6.6% |

Daily PED referrals for asthma in 2020 were compared to the previous 5 years grouped together; any significant variation within the 5 years was verified and excluded by comparing month by month, every year to each other. In Table S1, details on average daily acute asthma referrals to our PED are reported, on a monthly basis.

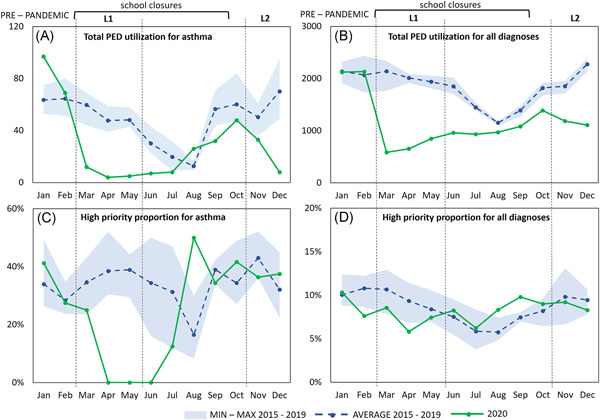

Compared to the reference years (2015–2019), in 2020 an overall 40% decrease of asthma‐related PED referrals was observed (Figure 1). During lockdown‐1 (March to May 2020), the total acute asthma referrals decreased abruptly by 85% compared to the same period in the previous 5 years (total referrals were 16, compared to a mean of 108 ± 11 in the years 2015–2019, p < 0.01) (Figure 1A). In the months between lockdowns, all asthma‐related PED referrals showed a similar decrease by 80% (20 vs. 98 ± 15, p < 0.01) from May 4 to the end of July, followed by a reduction by 44% in comparison to what is usually reported at the end of the summer. During lockdown‐2 (mid‐October to December 2020), we observed a reduction of 51% compared with the peak usually reported in the autumn (Figure 1A). The pattern for overall asthma referrals was similar to what was observed for overall PED referrals from all diagnoses (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Monthly referrals to the Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) of Sant'Orsola University Hospital of Bologna, Italy, related to the time periods 2015–2019 and 2020. (A) Asthma‐related PED referrals during 2015–2019 versus 2020; (B) PED referrals for all diagnoses during 2015–2019 versus 2020; (C) high priority asthma visits (%) during 2015–2019 versus 2020; (D) high priority visits (%) for all diagnoses during 2015–2019 versus 2020 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Importantly, there was an extraordinary decrease in the proportion of asthma‐related PED visits designated as high‐priority during lockdown‐1 and the subsequent weeks (Figure 1C). This decrease in high‐priority asthma visits was not observed for the overall high‐priority referrals from all diagnoses (Figure 1D). Outcomes of asthma‐related PED referrals are reported in Table 2. Hospital admissions in 2020 were higher in the prepandemic period and remarkably dropped during lockdown‐1 and the following months; none was registered in April, May, June, and August. A reduction in the use of SSOU was observed during the pandemic, except for August, presenting an increase in the total referrals and SSOU utilization.

Table 2.

Monthly asthma‐related referrals to the Pediatric Emergency Department of Sant'Orsola University Hospital corresponding to the years 2015–2019 versus 2020

| 2015–2019 (average ± SD; %) | 2020 (n; %) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tot | Discharge | SSOU | Admission | Tot | Discharge | SSOU | Admission | ||

| Jan | 63.6 ± 9.2 | 49.4 ± 6.8; 77.7% | 11.2 ± 5.4; 17.6% | 3.0 ± 2.7; 4.7% | 97 | 71; 73.2% | 15; 15.5% | 11; 11.3% | |

| Feb | 64.6 ± 10.9 | 54.0 ± 11.6; 83.6% | 8.2 ± 3.6; 12.7% | 2.4 ± 0.5; 3.7% | 69 | 57; 82.6% | 8; 11.6% | 4; 5.8% | |

| Mar | 59.8 ± 9.0 | 44.0 ± 7.1; 73.6% | 12.0 ± 3.3; 20% | 3.8 ± 2.3; 6.4 | 12 | 10; 83.4% | 1; 8.3% | 1; 8.3% | |

| Apr | 47.8 ± 7.0 | 40.0 ± 7.0; 83.7% | 5.4 ± 1.7; 11.3% | 2.4 ± 1.5; 5% | 4 | 4; 100% | 0; 0% | 0; 0% | |

| May | 48.2 ± 5.7 | 40.0 ± 6.8; 83% | 6.4 ± 2.7; 13.3% | 1.8 ± 1.3; 3.7% | 5 | 5; 100% | 0; 0% | 0; 0% | |

| Jun | 30.2 ± 7.1 | 25.8 ± 7.2; 85.4% | 3.6 ± 1.5; 12% | 0.8 ± 0.8; 2.6% | 7 | 7; 100% | 0; 0% | 0; 0% | |

| Jul | 19.8 ± 7.9 | 16.2 ± 7.9; 81.8% | 3.0 ± 1.0; 15.2% | 0.6 ± 0.9; 3% | 8 | 6; 75% | 1; 12.5% | 1; 12.5% | |

| Aug | 12.8 ± 2.5 | 11.6 ± 1.8; 90.6% | 1.0 ± 1.2; 7.8% | 0.2 ± 0.4; 1.6% | 26 | 19; 73.1% | 7; 26.9% | 0; 0% | |

| Sep | 56.6 ± 8.9 | 44.0 ± 11.4; 77.8% | 11.0 ± 2.9; 19.4% | 1.6 ± 1.1; 2.8% | 32 | 27; 84.4% | 4; 12.5% | 1; 3.1% | |

| Oct | 60.2 ± 16.0 | 49.8 ± 16.3; 82.7% | 8.6 ± 1.7; 14.3% | 1.8 ± 0.8; 3% | 48 | 40; 83.3% | 7; 14.6% | 1; 2.1% | |

| Nov | 50.4 ± 8.3 | 40.2 ± 8.8; 79.7% | 7.2 ± 4.5; 14.3% | 3.0 ± 1.6; 6% | 33 | 24; 72.7% | 6; 18.2% | 3; 9.1% | |

| Dec | 70.2 ± 14.9 | 58.8 ± 10.8; 83.8% | 8.8 ± 4.3; 12.5% | 2.6 ± 2.6; 3.7% | 8 | 7; 87.5% | 0; 0% | 1; 12.5% | |

Note: The type of treatment is also reported, that is, admission to hospital, short‐stay observation unit (SSOU), and discharge.

3.2. Air pollution

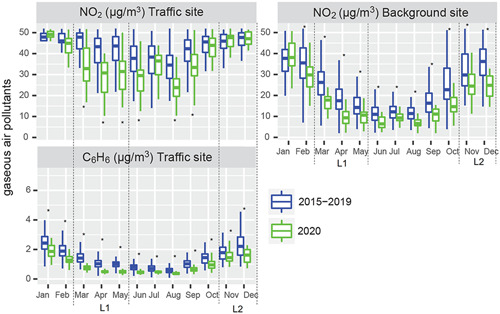

In Figure 2, the time series observed in 2020 is compared to the multiannual time series of daily mass loading for the gaseous pollutants NO2 and C6H6, measured at the urban background site and the urban traffic site identified above. Daily data are grouped month by month as boxplots, with the aim of better highlighting differences between 2020 and the reference years 2015–2019. The same representation for PM2.5 and PM10 is shown in Figure S1.

Figure 2.

Gaseous pollutants levels at the urban background site (NO2) and the traffic site (NO2 and C6H6) of the Arpae air quality monitoring network in Bologna, Northern Italy. The comparison is related to the time period 2015–2019 versus 2020: monthly boxplots are extracted by daily concentrations for 2020 and average daily concentrations for 2015–2019. The March to May calendar period (severe lockdown‐1) is indicated as L1 and the October to December calendar period (moderate lockdown‐2) is indicated as L2. *Above or below the boxplot refer to the statistically significant differences based on the t test [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Air pollutants behavior reflects the seasonal and interannual fluctuation in emission rates and climatological drivers. A detailed analysis of all these factors is beyond the scope of this study. For the purpose of this paper, we limited to exemplify changes in specific air pollution patterns that might have affected population exposure at the urban scale of Bologna.

Focusing on lockdown‐1, gaseous pollutants were strikingly reduced: NO2 concentrations in 2020 decreased on average by 46% (p < 0.01), while C6H6 decreased by 53% (p < 0.01), at the traffic site. When compared to historical levels, the differences of both gaseous pollutants gradually attenuated in late spring and summer, partially reflecting the slow, although not complete, return to regular activities that occurred in late spring and summer. With the second outbreak, the amplitude of these divergences resulted less clear and pronounced than during lockdown‐1.

In contrast, no significant impact of the lockdown measures is evidenced on the mass loading of PM10 and PM2.5, both at the urban background and traffic sites, consistently with other European cities. 22

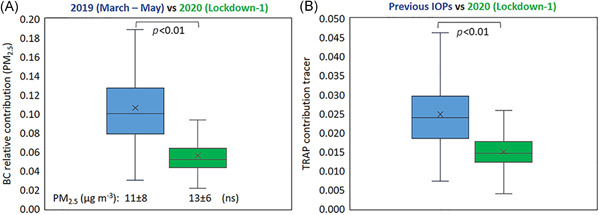

Nevertheless, considering PM chemical composition, it is noticeable that clear signals of reduced TRAP were observed during severe lockdown‐1. Figure 3A shows the contribution of BC mass to PM2.5 mass in 2019 versus 2020 (March to May). The average relative contribution of BC to PM2.5 significantly decreased from 11% to 6% (p < 0.01). Although a larger dataset would permit to obtain more robust results, this is in line with a recent study reporting, for Europe, a more pronounced reduction of BC concentrations in the range of 20%–40% during lockdown events in those countries that suffered more dramatically from the pandemic (e.g., Italy), 23 with respect to typical values for urban environment. 24

Figure 3.

(A) Black carbon relative contribution to PM2.5 during the March to May calendar period (lockdown‐1) in 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red); PM2.5 average mass concentrations are also reported (ns indicates that differences in mass concentrations between 2019 versus 2020 resulted as not significant); (B): f57 signal in the organic mass spectra of NR‐PM1 (TRAP signal) as measured in intensive observation periods (IOPs) during lockdown‐1 and during previous experimental campaigns at the urban background supersite of Arpae in Bologna. Not significant (ns) and p refer to Student's t test [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Accordingly, Figure 3B shows the TRAP contribution tracer, by comparing the measurements carried out during lockdown‐1 with those ones corresponding to IOPs during previous years, representative of a wide spectrum of seasonal/meteorological conditions. IOPs of previous years do not refer to the same control period 2015–2019 as other data. However, they were grouped together and compared to 2020, after verifying that lockdown values were significantly lower independently from any seasonal or interannual variation. The TRAP contribution tracer evidenced a marked decline by 40%, on average, in 2020, during the most severe lockdown, with respect to previous IOPs (p < 0.01).

3.3. Pollen

The main pollen plumes in 2020 were compared to the previous years to detect any significant variation. As showed in Figure S2, no remarkable variation beyond their interannual fluctuation was observed for the pollen allergens levels during lockdown periods.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings show that in 2020, during the first and second outbreak of SARS‐CoV‐2 across Northern Italy, overall childhood asthma exacerbations significantly decreased, as compared to the same calendar period of the previous 5 years (Figure 1). An increase in PED referrals for acute asthma restarted in August, continued in September, with a peak in October, anticipating the so‐called September asthma epidemics, the common burst of exacerbations generally observed with the start of the school year and due to a combination of infectious, allergic, environmental, and climatic triggers. 25 The peak in October was less pronounced than the previous years and this decreasing trend continued in November and December, when only eight asthma referrals were registered, likely reflecting the strict hygiene and social distancing measures adopted as a consequence of lockdown‐2.

We also observed a prevalent reduction trend of hospitalizations for asthma during the pandemic. Our PED and many others reported a substantial activity decrease by ca. 70%–80% during lockdown‐1, with drastic reductions in referrals for a wide spectrum of diagnoses. 1 , 2 This was attributed to the introduction of new guidance for primary care (e.g., phone selection triage procedure, more telehealth) and fear of exposure to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, leading to a higher risk of severe illness from delayed diagnosis. 1 , 2 , 26

A recent paper by Ulrich et al. 27 reported that the drastic decline in PED visits and admissions rates for asthma exacerbation was in excess of the decline observed in PED utilization for all diagnoses. Accordingly, in our study, the reduction in acute asthma referrals presents a similar pattern to that of all PED visits, but the fall in high‐priority asthma cases was strikingly higher during the most severe lockdown (Figure 1) and hardly explained solely by the reluctance to seek hospital care or by pandemic policies. In fact, in our pediatric clinic, only scheduled hospitalizations were canceled during the first lockdown, whereas acute admissions were not subject to any limitation. This effect specifically on severe asthma is rather ascribable to a combination of factors due to the complex mix of impacts related to the restriction measures.

Several studies reported how social distancing and stepped‐up hygiene measures determined a concomitant reduction in the diffusion of respiratory pathogens, leading to decreased respiratory tract infections, 3 , 8 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 and identify it as the main factor. Moreover, increased adherence to controller medications among the asthmatic population during lockdowns was demonstrated. 30 , 32 , 33

In the present paper, we aimed to highlight the additional potential role played by the reduced exposure to environmental factors—that is, air pollution and pollen—in this “anomalous” pattern of asthma exacerbations in 2020.

With regard to changes in air quality during the pandemic, the gaseous pollutants NO2 and C6H6, generally associated with fossil fuel combustion and positively correlated with vehicular traffic in the urban context, showed decreased concentrations during lockdown periods, more pronounced during lockdown‐1. In densely populated areas, they clearly mimicked a reduction of traffic‐related sources in concomitance with the restrictive measures, consistent with a mobility drop of 75%. 34 The abatement of traffic‐related pollutants is in good agreement also with a recent study by Cristofanelli et al., 35 showing how during lockdowns reduced anthropogenic emissions modified air pollutant levels in Northern Italy, not only in the proximity of urban or industrial agglomerates but even in remote sites. Their analysis clarified that these changes cannot be explained by differences in the meteorological conditions with respect to the previous years alone.

Unlike NO2 and C6H6, PM mass concentration was not clearly affected by lockdown measures. This can be explained by the myriad of sources and complex formation chemistry of PM in an urbanized environment, encompassing both natural and anthropogenic, primary and secondary sources, thus leading to mass concentrations driven to a large extent by nonurban and nontraffic sources. 20 By contrast, a substantial reduction in the contribution of specific chemical components of traffic‐related PM was observed during lockdown‐1, that is, BC and the TRAP contribution tracer.

Traffic‐related PM may gain relevance per unit mass of PM because of its higher oxidative potential and smaller size, leading to deposition in the deepest tracts of the respiratory system. 15 Thus, these observations point to PM less enriched in ultrafine particles and those coemitted components and micropollutants (e.g., BC, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), which are recognized as specific asthma triggers, able to drive a cascade of pro‐inflammatory and oxidative responses that increase the risks of acute pulmonary diseases. 36 As shown by mobility data, 34 the potential role of less inflammatory PM might have been amplified by less time spent outdoors and less movement during traffic rush‐hours. The risk associated with the proximity of children to strong local sources (exhaust and nonexhaust vehicular traffic) was therefore reduced, especially in inner‐city urban areas, where vehicular traffic normally presents a higher share of emissions. Nevertheless, the actual impact of these observations cannot be clearly elucidated due to the influence of a myriad of coinciding events/changes that occurred in society during 2020. Other authors recently discussed the potential factors involved in the decline in pediatric asthma exacerbations during lockdown, 37 including improved air quality levels; however, a relevant role of the fall in the concentration of air pollutants still has to be demonstrated. Recently, also Fan et al., 38 for example, failed to demonstrate such a direct correlation.

Pollen emissions, which are not impacted by changes in human behaviors and social restrictions, did not present substantial variations beyond their interannual variability during lockdown periods. On the other hand, the restrictive measures likely influenced exposure patterns in children by reducing physical activity and time spent outdoors.

In summary, several factors may explain the substantial decrease in the number of acute asthma PED referrals during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic in 2020, with the concomitant reduction of high‐priority codes. The reduction in respiratory pathogens other than SARS‐CoV‐2 is considered the by far most important one. In the present paper, we highlight that the restrictive measures adopted to limit the pandemic entailed a reduced exposure not only to viruses, but also, during severe lockdowns, to outdoor environmental allergens, and air pollution.

Our study presents some limitations. First, this is a monocentric study, so further multicenter analyses would be advisable to confirm our hypotheses. Second, the healthcare utilization and the environmental analysis are modeled separately and the ecological design approach bears some intrinsic biases, 39 relying on the descriptive analysis of data measured at the population level so that adjustment for individual risk factors is not achievable. Moreover, the TRAP contribution tracer and BC measurements were only available for shorter time frames compared to other data and therefore their evaluation did not cover the entire study period.

For the limitations reported above, our conclusions cannot provide the evidence needed to draw causal associations and do not aim to disentangle and quantify the impact of every single factor, including the involvement of viral infections, that was not analyzed. The parallel descriptions of the asthma‐related PED referrals and the potentially associated environmental triggers are, therefore, not to be intended in terms of causality.

Further investigations are needed to clarify in a more quantitative manner the role of each confounding trigger, driving synergistically variation in the clinical course of asthma. Nevertheless, due to the peculiarity of the lockdown periods, which acted as a big experiment of anthropogenic air pollution cleansing and radical changes of human lifestyle, this study represented a unique opportunity to observe these hypotheses using and exploring real data from a severely SARS‐CoV‐2 affected urban area, reflecting what occurred in many densely populated areas around the world.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Arianna Dondi: conceptualization (lead); methodology (equal); supervision (lead); writing original draft (equal); writing review and editing (equal). Ludovica Betti: data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); visualization (equal); writing original draft (equal); writing review and editing (equal). Claudio Carbone: data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); visualization (equal); writing original draft (equal); writing review and editing (equal). Ada Dormi: formal analysis (equal); validation (equal); writing review and editing (supporting). Marco Paglione: data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Matteo Rinaldi: data curation (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Maurizio Gualtieri: data curation (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Fabiana Scotto: data curation (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Vanes Poluzzi: data curation (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Marianna Fabi: formal analysis (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing review and editing (supporting). Marcello Lanari: conceptualization (lead); methodology (equal); supervision (lead); writing review and editing (lead).

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Air Quality measurements were supported and funded by the “Supersito” project, the Emilia‐Romagna Region (DRG no. 428/10 and DRG no. 1971/13), the Regional Agency for Prevention, Environment and Energy (DDG no. 29/2010), and the LIFE15 IPE IT013 Prepair project (https://www.lifeprepair.eu/).

Dondi A, Betti L, Carbone C, et al. Understanding the environmental factors related to the decrease in Pediatric Emergency Department referrals for acute asthma during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2022;57:66‐74. 10.1002/ppul.25695

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Air Quality and pollen data that support the findings of this study are available in the Arpae public repository. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://apps.arpae.it/qualita-aria/bollettino-qa-provinciale/bo; https://www.arpae.it/index.asp?idlivello=117. Asthma outcomes, HR‐ToF‐AMS and MetOne data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Masetti R, Corsini I, Leardini D, Lanari M, Pession A. Presentations to the emergency department in Bologna, Italy, during COVID‐19 outbreak. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4(1):1‐3. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matera L, Nenna R, Rizzo V, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic impact on pediatric emergency rooms: a multicenter study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):1‐12. 10.3390/ijerph17238753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taquechel K, Diwadkar AR, Sayed S, et al. Pediatric asthma health care utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(10):3378‐3387.e11. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papadopoulos NG, Custovic A, Deschildre A, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 on pediatric asthma: practice adjustments and disease burden. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2592‐2599.e3. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tregony S, Kimberly FG, Adam H, Kyle N, Jonathan MG. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on pediatric emergency department utilization for asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;18:717‐719. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-765RL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, Reddel HK. Asthma. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):783‐800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33311-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murrison LB, Brandt EB, Myers JB, Khurana Hershey GK. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1504‐1515. 10.1172/JCI124612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dondi A, Calamelli E, Piccinno V, et al. Acute asthma in the pediatric emergency department: infections are the main triggers of exacerbations. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:9687061. 10.1155/2017/9687061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papadopoulos NG, Christodoulou I, Rohde G, et al. Viruses and bacteria in acute asthma exacerbations–a GA 2LEN‐DARE* systematic review. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;66(4):458‐468. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02505.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor PE, Jacobson KW, House JM, Glovsky MM. Links between pollen, atopy and the asthma epidemic. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;144(2):162‐170. 10.1159/000103230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1581‐1592. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dye C, Reeder JC, Terry RF. Research for universal health coverage. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(199):199ed13 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khreis H, Kelly C, Tate J, Parslow R, Lucas K, Nieuwenhuijsen M. Exposure to traffic‐related air pollution and risk of development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Environ Int. 2017;100:1‐31. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowatte G, Lodge C, Lowe AJ, et al. The influence of childhood traffic‐related air pollution exposure on asthma, allergy and sensitization: a systematic review and a meta‐analysis of birth cohort studies. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;70(3):245‐256. 10.1111/all.12561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daellenbach KR, Uzu G, Jiang J, et al. Sources of particulate‐matter air pollution and its oxidative potential in Europe. Nature. 2020;587(7834):414‐419. 10.1038/s41586-020-2902-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mackway‐Jones K, Marsden J, Windle J. Emergency Triage: Manchester Triage Group. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang Q, Alfarra MR, Worsnop DR, Allan JD, Coe H, Canagaratna MR. Deconvolution and quantification of hydrocarbon‐like and oxygenated organic aerosols based on aerosol mass spectrometry. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39(13):4938‐4952. 10.1021/es048568l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ge X, Setyan A, Sun Y, Zhang Q. Primary and secondary organic aerosols in Fresno, California during wintertime: results from high resolution aerosol mass spectrometry. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:1‐15. 10.1029/2012JD018026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Canagaratna MR, Jayne JT, Jimenez JL, et al. Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26(2):185‐222. 10.1002/mas.20115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paglione M, Gilardoni S, Rinaldi M, et al. The impact of biomass burning and aqueous‐phase processing on air quality: a multi‐year source apportionment study in the Po Valley, Italy. Atmos Chem Phys. 2020;20(3):1233‐1254. 10.5194/acp-20-1233-2020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. D'Amato G, Cecchi L, Bonini S, et al. Allergenic pollen and pollen allergy in Europe. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;62(9):976‐990. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. European Environmental Agency . Air Quality and COVID‐19. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/air-quality-and-covid19/air-quality-and-covid19

- 23. Evangeliou N, Platt SM, Eckhardt S, et al. Changes in black carbon emissions over Europe due to COVID‐19 lockdowns. Atmos Chem Phys Discuss. 2020;21:2675‐2692. 10.5194/acp-2020-1005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandrini S, Fuzzi S, Piazzalunga A, et al. Spatial and seasonal variability of carbonaceous aerosol across Italy. Atmos Environ. 2014;99:587‐598. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.10.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen HA, Blau H, Hoshen M, Batat E, Balicer RD. Seasonality of asthma: a retrospective population study. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e923‐932. 10.1542/peds.2013-2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID‐19. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(5):e10‐e11. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ulrich L, Macias C, George A, Bai S, Allen E. Unexpected decline in pediatric asthma morbidity during the coronavirus pandemic. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(7):1951‐1956. 10.1002/ppul.25406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan K, Liang F, Tang H, Siong H, Yu W. Collateral benefits on other respiratory infections during fighting COVID‐19. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155(6):249‐253. 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pelletier JH, Rakkar J, Au AK, Fuhrman D, Clark RSB, Horvat CM. Trends in US pediatric hospital admissions in 2020 compared with the decade before the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):1‐13. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papadopoulos NG, Mathioudakis AG, Custovic A, et al. Childhood asthma outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic: findings from the PeARL multi‐national cohort. Allergy. Published online. 2021;76:1765‐1775. 10.1111/ALL.14787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Britton PN, Hu N, Saravanos G, et al. COVID‐19 public health measures and respiratory syncytial virus. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(11):e42‐e43. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Golan‐Tripto I, Arwas N, Maimon MS, et al. The effect of the COVID‐19 lockdown on children with asthma‐related symptoms: a tertiary care center experience. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(9):2825‐2832. 10.1002/ppul.25505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaye L, Theye B, Smeenk I, Gondalia R, Barrett MA, Stempel DA. Changes in medication adherence among patients with asthma and COPD during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2384‐2385. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Putaud J‐P, Pozzoli L, Pisoni E, et al. Impacts of the COVID‐19 lockdown on air pollution at regional and urban background sites in northern Italy. Atmos Chem Phys. 2020;2:1‐18. 10.5194/acp-2020-755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cristofanelli P, Arduni J, Serva F, et al. Negative ozone anomalies at a high mountain site in northern Italy during 2020: a possible role of COVID‐19 lockdowns? Environ Res Lett. 2021;16(7):074029. 10.1088/1748-9326/ac0b6a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Costabile F, Gualtieri M, Ancona C, Canepari S, Decesari S. Ultrafine particle features associated with pro‐inflammatory and oxidative responses: implications for health studies. Atmosphere. 2020;11(4):414. 10.3390/ATMOS11040414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guijon OL, Morphew T, Ehwerhemuepha L, Galant SP. Evaluating the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on asthma morbidity: a comprehensive analysis of potential influencing factors. Ann Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2021;127(1):91‐99. 10.1016/j.anai.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fan HF, He CH, Yin GQ, et al. Frequency of asthma exacerbation in children during the coronavirus disease pandemic with strict mitigative countermeasures. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(6):1455‐1463. 10.1002/ppul.25335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Villeneuve PJ, Goldberg MS. Methodological considerations for epidemiological studies of air pollution and the sars and COVID‐19 coronavirus outbreaks. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128(9):095001‐095013. 10.1289/EHP7411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

Air Quality and pollen data that support the findings of this study are available in the Arpae public repository. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://apps.arpae.it/qualita-aria/bollettino-qa-provinciale/bo; https://www.arpae.it/index.asp?idlivello=117. Asthma outcomes, HR‐ToF‐AMS and MetOne data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.