To the Editor:

We have seen the spotlight of lung ultrasound, which has found its definitive (finally!) consecration in the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic as a first‐level method for the evaluation of signs of pneumonia and in its monitoring. 1 It is known that the detection of B lines or vertical artifacts with nonhomogeneous distribution and an irregularity of the pleural line are the main signs of COVID‐19 pneumonia especially in the early phase. 2 As the disease progresses, the bilateral interstitial disease pattern worsens, by involving more and more lung areas in an increasingly severe manner (up to pulmonary edema visible as white lung areas on ultrasound) and up to induce consolidation areas, as evidence of complete pulmonary deaeration. 3 Almost a year and a half after the onset of the pandemic, many patients have more or less completely recovered. We have poor evidences about the chronic evolution of COVID‐19 infection and residual lung damage. Nowadays, there is an increasing number of requests for lung ultrasound in outpatients to evaluate lung damage after COVID‐19 infection/pneumonia.

In our early and small series of patients, we found an extreme heterogeneity of patients from a clinical and anamnestic point of view. Particularly, it seems appropriate to distinguish patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection who were hospitalized or at least performed an imaging study in the course of acute illness, compared to patients who spent the acute phase at home without carrying out any assessment. In the first case, it is possible to try to make a comparison with the previous reports, but pointing out how it is difficult to compare the data of different methods and also of the same method performed with different reporting criteria. In the second case, a comparison is absolutely not possible, thus reporting the current condition only. In our sample, almost all of the patients who spent the acute phase at home had a normal pattern with A lines, in the absence of pathological artifacts. That finding is consistent with the fact that those patients presented mild symptoms that did not require hospitalization (mild phenotype) and did not induce relevant or permanent lung damage. In our opinion, those patients do not require further investigations or follow‐up, unless the persistence of respiratory symptoms.

A difficult case to evaluate is certainly the patient with a previous COVID‐19 infection who has not performed any assessment in the acute phase, but shows signs of lung damage on the outpatient ultrasound. It is not possible to state with certainty whether those signs are entirely due to COVID‐19 pneumonia or to a previous or coexisting pulmonary disease. Therefore, we suggest to perform subsequently lung function tests and second‐level imaging method in those patients, especially in those who report significant symptoms.

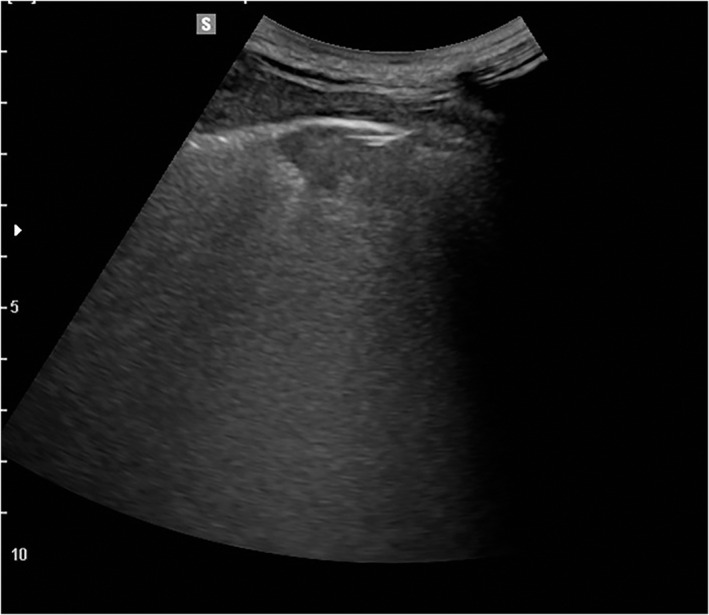

In the case of the patient with previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infection who has undergone investigations and/or hospitalization, a certain degree of comparison can be performed. On lung ultrasound, we expect to find the disappearance or decrease of signs of COVID‐19 pneumonia, in particular, the disappearance of the consolidation areas, the reduction of the areas involved, and the amount of B lines visible on each lung area, up to a normal pattern with A lines (Figures 1 and 2). The ultrasound finding is certainly conditioned by the clinical severity of the patient during the acute phase and by the timing of the examination. In our case series, a patient previously admitted to intensive care unit for a severe respiratory failure due to COVID‐19 pneumonia still presented a white lung area and a consolidation area on lung ultrasound control, along with some areas with non‐confluent B lines and a widespread irregularity of the pleural line.

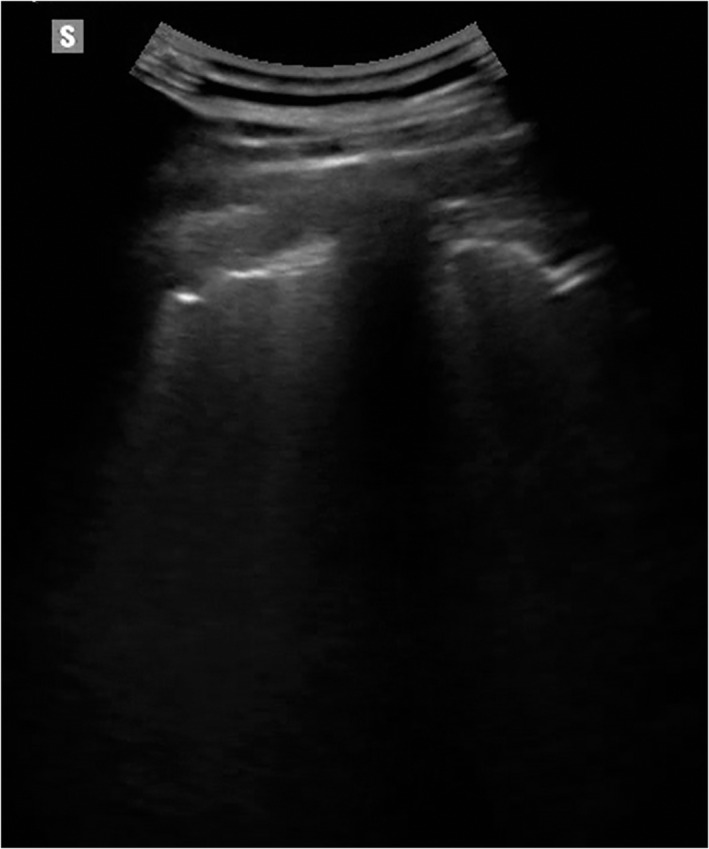

Figure 1.

Lung ultrasound on a 42‐year‐old outpatient 3 months after the acute phase of the COVID‐19 infection. The patient had a mild form of pneumonia that did not require hospitalization. The image shows an irregularity of the pleural line which is thickened or interrupted in some segments, more evident in the basal dorsal lung fields.

Figure 2.

Lung ultrasound on a 54‐year‐old outpatient 1 month after the acute phase of the COVID‐19 infection. The patient presented with a severe form of pneumonia that required admission to intensive care for invasive ventilation. The image shows a residual hypoechoic subpleural consolidation, a sign of residual de‐aeration of the evaluated lung field.

The latter finding seems to be the most frequently residual sign from COVID‐19 pneumonia, also visible in patients who developed mild pneumonia (Figure 1). In our series, patients who had been treated for a mild form of pneumonia showed a clear irregularity of the pleural line at 3 months (similar to initial pictures of chronic fibrosing interstitial disease) in the dorsal basal fields, often in the absence of other pathological signs. The optimal situation is to perform an ultrasound follow‐up of the patient during and after the COVID‐19 infection, by using the same method and the same reporting scheme. In the few cases examined, we used the LUS score, thus showing a decrease in score number, but whether this score gradually decreases to zero or settles on a severity score over time is not known yet.

A first question to answer is whether lung ultrasound is relevant enough to be considered as a screen/control method for an accurate assessment of residual lung damage; we should point out that lung ultrasound can evaluate only changes that reach the pulmonary pleura. Notably, the association of ultrasound with clinical and laboratory/spirometric data can strengthen subsequent clinical choices. Secondly, it is relevant to establish the timing of control both from the acute phase of the infection, according to the clinical history and phenotypes of the patients, and over time (we suggest 3, 6 and 12 months). Thirdly, it is important to understand the evolution of lung damage over time from a pathophysiological and pathological point of view; indeed, some patients had a complete restitutio ad integrum on the one hand and others who will develop chronic interstitial disease on the other. In the latter case, the ultrasound findings could be similar to that known for chronic lung diseases with pleural line irregularities, irregular B lines, and small subpleural consolidations.

We hope that future controlled comparative studies can answer those questions. Furthermore, the publication of specific guidelines, with a clear definition of the study and reporting methods, will allow a comparison of patients between different physicians.

Authors declare no funding sources and no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Boccatonda A, Cocco G, Ianniello E, et al. One year of SARS‐CoV‐2 and lung ultrasound: what has been learned and future perspectives. J Ultrasound 2021; 24:115–123. 10.1007/s40477-021-00575-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Volpicelli G, Gargani L, Perlini S, et al. Lung ultrasound for the early diagnosis of COVID‐19 pneumonia: an international multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47:444–454. 10.1007/s00134-021-06373-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sofia S, Boccatonda A, Montanari M, et al. Thoracic ultrasound and SARS‐COVID‐19: a pictorial essay. J Ultrasound 2020; 23:217–221. 10.1007/s40477-020-00458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]