Abstract

Objective

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eventually recommended wearing masks in public to slow the spread of the coronavirus, the practice has been unevenly distributed in the United States.

Methods

In this article, we model county‐level infrequent mask usage as a function of three pillars of conservatism: (1) Republican political leadership (percentage of votes for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election), (2) conservative Protestantism (percentage evangelical Christian), and (3) right‐wing media consumption (Google searches for Fox News).

Results

Our analyses indicate that mask usage tends to be lower in counties with greater support for President Trump (in majority Trump counties), counties with more evangelical Christians, and areas with greater interest in Fox News.

Conclusion

Given the effectiveness of masks in limiting the transmission of respiratory droplets, conservative ideological resistance to public health and recommended pandemic lifestyles may indirectly support the spread of the coronavirus.

Keywords: COVID‐19, health behavior, politics

After spreading around the world in a matter of months, the novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19) has become a leading cause of death in the United States. According to the Coronavirus Resource Center at Johns Hopkins University (2021), nearly 600,000 Americans have already died from COVID‐19. Although the United States accounts for only 4 percent of the global population, it has contributed 17 percent of all COVID‐19 deaths worldwide. In an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) have proposed several mitigation strategies like staying home, social distancing, hand sanitizing, and wearing masks or other protective face coverings. The recommendation of wearing masks has been particularly contentious in the United States. Because wearing a mask is so important for public health, we must begin to seriously model this polarization. The fundamental question is whether certain populations are more or less likely to wear masks or other protective face coverings in public during the pandemic.

In this article, we consider the association between various indicators of contemporary conservatism and mask usage at the county level.1 During the pandemic, three pillars of conservatism (Republican political leadership, conservative Protestantism, and right‐wing media) have received a great deal of public attention and scrutiny for supporting widespread resistance to public health recommendations and mask mandates. On July 8, Salon reported that “Fox News hosts downplay surge in coronavirus cases [and] dispute science on masks and social distancing” (Derysh, 2020). On August 20, Yahoo! News advised that “Freedom of religion doesn't mean freedom from mask mandates” (Finn, 2020). On September 17, The New York Times asked, “What is it with Trump and face masks?” (Krugman, 2020). Although not representative of the spectrum of conservatism in the United States, all of these reports (and many more like them) point to the same general concern: Conservative populations may be less likely to wear masks or other protective face coverings during the coronavirus pandemic.

In the pages that follow, we explore relevant research concerning the three pillars of conservatism and related rhetoric surrounding the coronavirus pandemic and mask usage. We then model county‐level mask usage as a function of county‐level Republican political leadership (percentage of votes for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election), conservative Protestantism (percentage of the population identifying as evangelical Christian), and right‐wing media consumption (Google searches for Fox News). After summarizing our key results, we discuss the contributions and limitations of our study. We end with some important directions for future research on the social patterning of mask usage and other elements of emerging pandemic lifestyles.

THREE PILLARS OF CONSERVATISM DURING THE PARTISAN PANDEMIC

Pillar 1: Republican political leadership

Populations that follow Republican political leadership, in general, and President Trump, in particular, may be especially resistant to public health recommendations and the formation of healthy pandemic lifestyles (e.g., staying at home, social distancing, and wearing masks) because they tend to hold more conservative political ideologies, including negative views of “big government” and science and seemingly counterproductive beliefs concerning the pandemic itself (Hill, Gonzalez, & Davis, 2021).

Republicans generally mistrust “big government” because it is often framed by conservative rhetoric as a malignant federal bureaucracy that exists to serve its own interests by extracting ever‐increasing taxes and by diminishing personal freedom and liberty (Frank, 2007). While there is a longstanding tension between conservative views of “big government” and the desire to federally fund the military‐industrial complex and internal policing projects like Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the concept of the “deep state” has recently afforded some reconciliation. Because many Republicans view the “deep state” as a class of left‐leaning, federal bureaucrats that operates beneath the normal levers of power to principally oppose conservative policies, in general, and the Trump administration, in particular, Republicans are able to hold two apparently contradictory positions simultaneously. First, the federal government is beneficial because it is uniquely suited to pursue conservative interests. Second, the federal government is detrimental because it is unable to achieve its full potential due to competing liberal interests that are morally repugnant and hidden from the public. In fact, Trump was elected in 2016, in part, by campaigning vigorously on the promise of “draining the swamp” of bureaucracy in Washington D.C. by rooting out the problem of entrenched government officials.

Another reason that Republicans may be less likely to wear masks is because many Republicans mistrust science, claiming that its proponents and products are often mobilized against conservative ideologies and interests (Motta, 2018a, 2018b). Anti‐intellectualism runs deep in American conservative politics and is commonly expressed through an adversarial relationship vis‐à‐vis science. For example, conservative scientists are regularly funded by corporations and industry to act as “merchants of doubt” and to shape public opinion and dilute scientific consensus on issues ranging from the dangers of smoking to the realities of climate change (Oreskes & Conway, 2010). Prior to the pandemic, a national poll indicated that Republicans were less likely than Democrats (27 percent vs. 43 percent) to report having “a great deal” of confidence in scientists to act “in the best interests of the public” (Funk et al., 2019). In the same poll, the partisan divide extended to the appropriate role of scientists when conducting policy‐relevant research and to faith in the fidelity of scientific reasoning. On the one hand, Republicans were less likely than Democrats (43 percent vs. 73 percent) to believe that “scientists should take an active role in policy debates” (Funk et al., 2019). On the other hand, more Republicans than Democrats (55 percent vs. 36 percent) believed that “scientists’ judgements are just as likely to be biased as other people's” (Funk et al., 2019).

Republican mistrust of public health and health scientists was evident from the early stages of the pandemic when President Trump and his associates downplayed the threat as a “fraud” perpetrated by the “deep state,” as “fake news,” as a “liberal hoax,” and as an “impeachment scam” (Bunch, 2020; Van Bavel, 2020). Bunch (2020) notes that “downplaying the health warnings from white‐coated eggheads with all their university degrees—in a way that amplified Trump and ridiculed media—was right in their wheelhouse.” Commenting on America's distrust of experts during the pandemic, Merkley (2020) argues that “the problem isn't just partisanship; it's the anti‐intellectualism in American life.” Beauchamp (2020) explains that the Republican response to the coronavirus is clearly imprinted with the “DNA” of “modern American conservatism” and “a disdain for the country's intellectual elite.” In the first week of March, a national poll showed that Republicans were less likely than Democrats (6 percent vs. 21 percent) to be “very worried” about the coronavirus (Frankovic, 2020). By the second week of March, another national poll indicated that Republicans were still less likely than Democrats (45 percent vs. 74 percent) to be “very worried or somewhat worried” about the coronavirus (Sanders, 2020). In the same poll, Republicans were also more likely than Democrats (29 percent vs. 58 percent) to believe that the threat of the coronavirus had been exaggerated.

The trust of Republican leadership and associates on matters related to health and health care was demonstrated during the month of April as President Trump shifted from downplaying the pandemic to blaming others like the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO). During this period, President Trump also began to receive increased scrutiny from the media and scientists for recommending a malaria drug (hydroxychloroquine) and an antibiotic (azithromycin) without adequate clinical evidence of safety and effectiveness. President Trump effectively generated adversarial institutional relationships by impugning public health organizations and by pushing reckless treatments on the general public. In the end, these decisions forced public health and front‐line medical professionals to openly challenge the political authority of the President. According to Aleem (2020), “messaging from Trump and hard‐right news outlets like Fox News had diverged from consensus among scientists and public health experts around the world.” While lamenting the “politicization of public health,” Robert Faris, research director at Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, noted that “having Trump and Fauci on the same public stage at the same time is an untenable position for right‐wing media…” (Stanley‐Becker, 2020). Toward the end of April, a national poll asked about levels of trust in the medical advice received from various sources (Grenier, 2020). This poll showed that Republicans were more likely than Democrats to trust the medical advice of President Trump (75 percent vs. 8 percent) and Vice President Pence (67 percent vs. 8 percent). The poll also indicated that Republicans were less likely than Democrats to trust the WHO (24 percent vs. 74 percent), the CDC (60 percent vs. 76 percent), and Dr. Fauci (52 percent vs. 72 percent).

In early April, the CDC began to recommend that people wear cloth masks or other protective face coverings in public places, after having originally discouraged the use of masks by the general public. During the next coronavirus task force news conference, President Trump informed the public that masks were voluntary and that he would not be wearing one: “In light of these studies, the CDC is advising the use of nonmedical cloth face covering as an additional voluntary public health measure. So it's voluntary; you don't have to do it. They suggested for a period of time. But this is voluntary. I don't think I'm going to be doing it” (Smith, 2020). For the most part, President Trump refused to wear a mask in public during the pandemic (Collins & Jackson, 2020; Fritze, 2020; Naylor & Wise, 2020; Smith, 2020). He ridiculed the press and Joseph Biden for wearing masks (Smith, 2020). Bolstered by early mixed‐messaging from public health officials, Trump repeatedly questioned CDC recommendations and the science supporting the efficacy of masks (Collins & Jackson, 2020; Graham et al., 2020; Naylor & Wise, 2020; Smith, 2020). On September 16, CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield told Congress that masks are “the most important, powerful public health tool we have” to slow the spread of the coronavirus and that he would “even go so far as to say that this face mask is more guaranteed to protect me against COVID than when I take a COVID vaccine” (Collins & Jackson, 2020). Shortly after these comments, President Trump challenged Dr. Redfield during his White House briefing, suggesting that “the mask is a mixed bag” and that the CDC Director had “made a mistake” or was “confused” (Collins & Jackson, 2020; Naylor & Wise, 2020). Dr. Redfield then responded with the following Twitter post: “The best defense we currently have against this virus are the important mitigation efforts of wearing a mask, washing your hands, social distancing and being careful about crowds” (Collins & Jackson, 2020).

In the end, the Republican resistance to wearing masks and other public health measures is mostly fueled by diminished confidence in public health and an intense devotion to Trump. Krugman (2020) explains that “anti‐mask agitation isn't really about freedom, or individualism, or culture. It's a declaration of political allegiance, driven by Trump and his allies.” While Trump supporters are highly skeptical of established social institutions like the federal government and the CDC, they are highly trusting of and loyal to Trump because they see him as an “outsider” and as a “truth‐teller” (Shugerman, 2018). For all of these reasons and many others, Trump has had a tremendous impact on the ways in which large populations think about public health and respond to public health recommendations during the pandemic (Graham et al., 2020; Shepherd, MacKendrick, & Mora, 2020). Along these lines, national polls have indicated that Republicans were much less likely to have “worn a mask or face covering when in stores or other businesses all or most of the time” during June (53 percent vs. 76 percent) and August (76 percent vs. 92 percent) (Kramer, 2020).

We fully acknowledge that our focus on Republican political leadership mostly centers around President Trump. While President Trump's positions have been relatively consistent, Republican governors have not been uniform in their responses to the pandemic. There are two primary explanations for this. The first explanation is mixed political leadership. Republicans control 26 of 50 governorships, including left‐leaning states like Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont that have reliably voted for Democrats in presidential elections over the past two decades. Individuals in blue states with red governors may exhibit political ideological characteristics that are more closely akin to states with Democrat governors. The second explanation is that while Republican governors typically follow the policies and preferences of the current federal government, there is variability in their executive responses (e.g., state mask mandates) and the degree to which they are beholden to the Trump administration for electoral survival. For example, public polling from late 2019 suggests that the four Republican governors in states carried by Hillary Clinton (mentioned above) are among the most popular (Morning Consult, 2020). Their popularity may insulate them from pressure to adopt more hardline conservative policy positions during the pandemic.

Pillar 2: Conservative protestantism

Certain religious populations may also resist public health recommendations and the adoption of healthy pandemic lifestyles because they tend to hold more negative views of science and scientists and strong religious beliefs concerning the pandemic (Hill, Gonzalez, & Burdette, 2020; Hill, Gonzalez, & Upenieks, 2021; Perry, Whitehead, & Grubbs, 2020). Several studies show that more religious populations tend to report less trust in science as a social institution and more anti‐science attitudes (Evans, 2013; Gauchat, 2008, 2012). Of course, these positions are not representative of all religious groups. There is at least some evidence to suggest that conservative Protestant denominations, including evangelical Protestants, may be less literate in science and expressly critical of the scientific community and the potential benefits of scientific progress (Ellison & Musick, 1995; Evans, 2013; Gauchat, 2008). For example, studies show that conservative Protestants are often less concerned with environmental degradation, less trusting of the findings of climate scientists, and more likely to endorse “a polluting creed” (Sherkat & Ellison, 2007; Smiley, 2019).

Many conservative Protestant denominations see the Bible as the ultimate source of authority and direction in the interpretation and experience of personal life and world events (Ellison, Bartkowski, & Segal, 1996). In contrast to the positivist logic implied by the scientific method, so‐called biblical literalists assess the legitimacy of scientific information by its apparent compatibility with scripture (Ellison & Musick, 1995). Religious conservatives, guided by pastors and other religious elites, often draw on religious scripture to oppose scientific recommendations that are perceived as immoral or defined as encroaching on religious liberty or the will or grace of God. Moreover, tensions between religion and science are often rooted in fears concerning the profane influence of science on society (Evans, 2013) and a “social conflict between institutions struggling for power” (Evans & Evans, 2008:97).

Along these lines, we argue that the belief systems of conservative Protestantism are likely to serve as an ideological basis for resisting public health recommendations and healthy pandemic lifestyles. These themes are regularly represented in the media. In May, a state legislator from Ohio wrote on social media that he would not wear a mask during the pandemic because “the face represents the image of God” (Pinckard, 2020). He explained: “This is the greatest nation on earth founded on Judeo‐Christian principles. One of those principles is that we are all created in the image and likeness of God. That image is seen the most by our face. I will not wear a mask” (Pinckard, 2020). In August, a reverend and Florida state representative sued to challenge a mask mandate in Manatee County (Finn, 2020). The key argument of the lawsuit is that the mask mandate “should not apply within churches, synagogues and other houses of worship because it interferes with the ability to pray” and would make “it more difficult…to preach and for members of the choir to sing” (Finn, 2020). In September, a former gubernatorial candidate in Missouri wrote on social media that wearing a mask is part of a “demonic ritual” designed to “take away God‐given rights” (Grzeszczak, 2020). Later that month in Ohio, over two dozen parents sued the state's health director over mask mandates in schools, claiming such rules encroached on their “religious beliefs” and their “ability to raise their children as they wish” (Grzeszczak, 2020).

These media accounts are further supported by recent opinion polls and published research. For example, national polls have shown that, from April to June, white evangelicals were less likely to have worn a mask in public than the population in general (Burge, 2020). Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs's (2020:2) analysis of national survey data showed that Christian nationalism, “an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of American civic life with a particular type of Christian identity and culture” (e.g., believing that “The federal government should advocate Christian values”), was inversely associated with having worn a mask in public during the month of May. Impressively, Christian nationalism was the second strongest predictor of mask usage in a model that included adjustments for age, race, ethnicity, marital status, the presence of children, education, income, region of residence, political affiliation, political orientation, religious affiliation, and general religiosity.

Pillar 3: Right‐wing media consumption

Finally, populations that consume more right‐wing media may resist public health recommendations and healthy pandemic lifestyles because they are generally exposed to more conservative messages, suspicion of government and science, and misinformation. Although political media consumption is primarily driven by prior political leanings (Stroud, 2008), research suggests that selective exposure to news media can reinforce and strengthen preexisting belief systems (Bolce, De Maio, & Muzzio, 1996; Feldman et al., 2014; Gil de Zúñiga, Correa, & Valenzuela, 2012), especially for Republicans (Feldman et al., 2012). For example, Fox News viewership has been associated with greater anti‐immigrant sentiment (Gil de Zúñiga, Correa, & Valenzuela, 2012), skepticism concerning climate change and global warming (Feldman et al., 2012; Krosnick & MacInnis, 2010), and biases concerning the Iraq War (Morris, 2005), even after accounting for personal political affiliation.

Right‐wing media audiences appear particularly vulnerable to misinformation, with such content being shared more broadly by right‐wing users on social media and for‐profit fake news being more lucrative when stories have a right‐wing slant (Kshetri & Voas, 2017; Narayanan et al., 2018; Vojak, 2018). This is likely due to a conservative preference for bias‐confirming content (Iyengar & Hahn, 2009; Morris, 2005). Fox News viewers, for example, have reported a greater preference for entertainment‐based news aligned with preexisting beliefs, rather than in‐depth content (Morris, 2005). Studies confirm that Fox News has been an egregious source of false or misleading claims during the coronavirus pandemic. Compared to other media outlets, right‐wing media sources like Fox News have shared misinformation regarding the virus more frequently and consistently downplayed the severity of the crisis. For these reasons, consumers of right‐wing news are more likely to believe that the health risks associated with COVID‐19 have been overstated by the mainstream media and public health officials. Indeed, Fox News viewers are less likely to report feeling personally vulnerable to the virus and more likely to accept outright misinformation and conspiracy theories concerning the pandemic (Calvillo et al., 2020; Motta, Stecula, & Farhart, 2020).

Fox News media also regularly casts doubt on the efficacy of masks, even when some portion of the content seems to recommend their use. On July 2, Fox News posted a video and a story with the following headline: “Does wearing a face mask pose any health risks?” (Foxnews.com, 2020a). This content was posted after President Trump began to endorse face masks. In the video, President Trump stated, “If people feel good about it, they should do it.” Just above the running headline “Masked Messages: Mixed Conclusions on Facial Covering Effectiveness,” Dr. Marc Siegel, a practicing internist and Fox News medical contributor, then offered the following conclusion to a brief summary of the scientific literature on masks: “Sweat from exercise can make the mask become wet more quickly, which makes it more difficult to breathe and promotes the growth of, yes, bacteria and viruses.” On July 7, prominent Fox News host Tucker Carlson informed his viewers that “Many schools that do plan to reopen will do so under a series of restrictions that have no basis of any kind in science. It's kind of a bizarre health theater. Students will be kept six feet apart, everyone will have to wear a mask, class sizes will be limited…” (Porter, 2020).

On August 12, White House coronavirus advisor Dr. Scott Atlas appeared on the Tucker Carlson show to say that “There is no real good science on general population, widespread in all circumstances, wearing masks” (Foxnews.com, 2020b). Dr. Atlas went on to note that “the WHO itself says that there is no sound science for general populations wearing masks.” On August 14, Dr. Siegel returned to Fox News to tell Tucker Carlson that (a) Biden's proposed national mask mandate is based on the “the politics of fear and the power of science, politics of fear, big government edition,” (b) there is no “proof” that wearing a mask can help to stop the spread of the coronavirus, (c) bike riders would likely experience “more damage to the brain from forgetting to wear their helmets because they are so worried about these government ideas about excess masking,” (d) wearing masks during sex will “definitely ruin the romance,” and that (e) “a Wisconsin state agency has come out with a decree that, even if you are at home on a Zoom call, you should wear a mask, even if you are alone.” Dr. Siegel ended his report by simply stating, “No science.” (Parke, 2020).

Hypotheses

To summarize, our core arguments are that populations (not individuals) that follow the leadership of President Trump, identify as evangelical Protestant, and consume more Fox News are especially likely to (1) deny health information from health scientists (mistrust of science), (2) accept health misinformation from unqualified political and religious leaders (misguided authority), and (3) reject public health restrictions on individual behavior (violent individualism). In accordance with these general arguments, we developed three hypotheses to guide our analyses: (H1) Populations with larger percentages of votes for Trump in the 2016 presidential election will tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic. (H2) Populations with larger percentages of evangelical Christians will tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage. (H3) Populations with greater media interest in Fox News will tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage.

DATA

To formally test our hypotheses, we employ survey data estimating facial mask usage from The New York Times (The New York Times and Dynata, 2020), political data from public voting records, religious affiliation data from the 2010 U.S. Religion Census (Grammich et al., 2018), demographic characteristics from the 2018 American Community Survey: 5‐Year Estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019), and news media interest from Google Search Trends (Google, 2020). While our main level of analysis is U.S. counties, Google Search Trends are assessed at the level of designated media markets areas (DMAs), a nonoverlapping aggregation of U.S. counties to 210 media markets based on similar population clusters. Governor's political affiliation is also measured at the state level. Our final analytic sample consists of 3083 U.S. counties.

MEASURES

Infrequent Mask Usage is measured with aggregated survey data published by The New York Times. The county‐level estimates were created using survey weighting for age, gender, and census tract (The New York Times, 2020). These weighted estimates are based on a larger survey conducted by a survey research firm between July 2 and 14. Approximately 250,000 survey participants were asked, “How often do you wear a mask in public when you expect to be within six feet of another person?” Original response categories include never, rarely, sometimes, frequently, and always. To isolate infrequent mask use, we coded never and rarely as (1) and sometimes, frequently, or always as the reference category (0). In our preliminary analyses, we assessed the construct validity of infrequent mask usage by testing associations with sheltering‐in‐place rates provided by Google (Google, 2020). Our analyses revealed a moderate inverse correlation (r = –0.46) between infrequent mask usage and shelter‐in‐place rates. In other words, areas spending more time at home tend to exhibit more frequent mask usage.

Conservatism. As mentioned, we conceptualize three pillars of conservatism. We measure Republican political leadership as the county's percentage of votes for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Alaska is exceptional because they report only state‐level voting rates. We measure conservative Protestantism as the county's percentage of evangelical Christians. These data were collected through the 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations and Membership Study (Grammich et al., 2018). Right‐wing media consumption is assessed using Google Search Trends to capture “Fox News” searches over the past 12 months across individual DMAs. Each DMA value represents the popularity of the search term on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being the maximum search popularity out of all DMAs and all searches. We use this measure to indicate active interest in and attention toward Fox News. Google Search Trends have been validated for use in a range of research contexts and for use with survey data, voting data, and ecological data (Bail, Brown, & Wimmer, 2019; Reyes, Majluf, & Ibáñez, 2018; Scheitle, 2011; Stephens‐Davidowitz, 2014; Swearingen & Ripberger, 2014).

Background Variables. Our analyses include a range of county‐level background variables that are at least theoretically related to mask usage, including the (1) percentage of adults aged 65 and older, (2) Gibbs–Martin racial‐ethnic diversity index (Blau, 1977; Gibbs & Martin, 1962), (3) percentage of college graduates, (4) 5‐year average county unemployment rate, (5) median income, and (6) population density. Given that median income and population density were skewed, both variables were log‐transformed for subsequent regression analyses. We also control for governor's political party (1 = Republican; 0 = Other). With the exception of the diversity index, all county‐level background variables were collected through the 2018 American Community Survey: 5‐Year Estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Governor's political party was determined through publicly accessible records from the National Governor's Association for July 2020 (National Governors Association, 2020).

ANALYSIS

Our analysis proceeds in three steps. In Table 1, we present descriptive statistics for all study variables, including variable ranges, means, and standard deviations. In Table 2, we use weighted least squares (WLS) regression to model the continuous percentage of infrequent mask usage. Model 1 tests whether mask usage varies according to Fox News interest and background variables. Model 2 tests whether mask usage varies according to the percentage of evangelical Christian and background variables. Model 3 tests whether mask usage varies according to the percentage of Trump votes and background variables. This model also employs a squared term to formally test the linearity of the association between Trump votes and mask usage. In preliminary analyses, we observed that the nature of the association between Trump votes and infrequent mask usage varied across the distribution of Trump votes. Finally, Model 4 presents our full model with all conservatism measures and background variables to assess any changes among our correlated predictors.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for selected study variables

| Variable range | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage infrequent mask usage | 0.10–55.80 | 16.26 | 9.64 |

| Fox News interest | 14–100 | 51.93 | 11.29 |

| Percentage evangelical Christian | 0–130.87 | 23.31 | 16.27 |

| Percentage Trump vote | 8.34–95.27 | 63.52 | 15.55 |

| Percentage over age 65 | 3.8–55.60 | 18.40 | 4.54 |

| Gibbs–Martin Diversity Index | 0–198.14 | 43.67 | 36.52 |

| Percentage college graduate | 0–78.53 | 21.60 | 9.41 |

| 5‐Year unemployment rate | 0–26.45 | 5.74 | 2.75 |

| Median income | 33,638.95–18,1724.27 | 67,732.60 | 16,629.91 |

| Republican governor | 0–1 | 0.56 | |

| Population density | 0.15–72,052.96 | 272.82 | 1810.99 |

Notes: n = 3083.

TABLE 2.

Weighted least squares regression of infrequent mask usage

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fox News interest | 0.125*** | 0.143*** | ||

| (0.013) | (0.013) | |||

| Percentage evangelical Christian | 0.045*** | 0.028** | ||

| (0.009) | (0.010) | |||

| Percentage Trump votes | –0.320*** | –0.396*** | ||

| (0.041) | (0.041) | |||

| Percentage Trump votes (squared) | 0.003*** | 0.004*** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| Percentage over age 65 | –0.311*** | –0.339*** | –0.350*** | –0.321*** |

| (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.030) | |

| Gibbs–Martin Diversity Index | –0.062*** | –0.076*** | –0.074*** | –0.064*** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Percentage college graduate | –0.090*** | –0.056** | –0.057* | –0.112*** |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.024) | (0.024) | |

| 5‐Year unemployment rate | –0.305*** | –0.331*** | –0.319*** | –0.259*** |

| (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.060) | (0.060) | |

| Median income (logged) | –4.278*** | –6.462*** | –7.598*** | –3.012** |

| (0.978) | (0.965) | (0.942) | (1.016) | |

| Republican governor | 3.606*** | 3.362*** | 3.182*** | 3.024*** |

| (0.268) | (0.278) | (0.278) | (0.273) | |

| Population density (logged) | –1.154*** | –1.406*** | –1.312*** | –1.186*** |

| (0.090) | (0.091) | (0.094) | (0.095) | |

| R‐squared | 0.442 | 0.423 | 0.439 | 0.470 |

Note: n = 3083. Republican governor is state‐level. All other measures are county level.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001 (two‐tailed test).

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

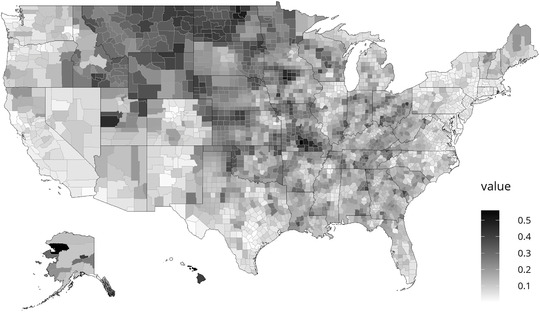

In Table 1, we show that, on average, 16 percent of county residents in the United States reported wearing a face mask in public rarely or never. We note considerable variation in mask usage across counties. Between 0.10 percent and 55.80 percent of county residents regularly refuse to wear masks in public. Figure 1 shows the average regional variation in mask usage. According to Figure 1, the percentage of infrequent mask usage is highest in counties concentrated in the Mountain West (e.g., Montana and Wyoming), Midwest (e.g., Iowa and Missouri), and South (e.g., Oklahoma and Louisiana).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of infrequent mask usage by U.S. county

Regression analysis

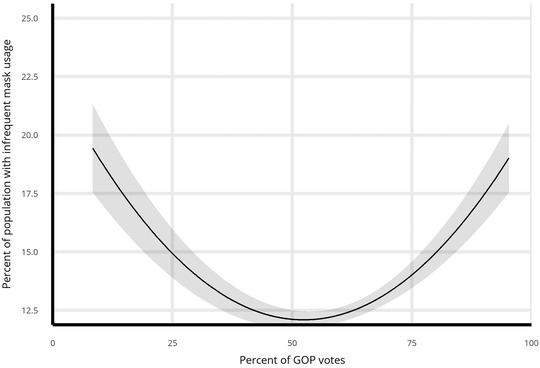

Given that our regression results are remarkably consistent across models, we focus our interpretation on the fully adjusted model in Table 2. According to Model 4, the percentage of infrequent mask usage tends to be higher in DMAs with greater Fox News interest (b = 0.143, p < 0.001) and counties with more evangelical Christians (b = 0.028, p < 0.001). Model 4 also indicates that the association between Trump votes and mask usage is curvilinear. While the sign of the coefficient for Trump votes is negative (b = –0.396, p < 0.001), the sign of the coefficient for squared Trump votes is positive (b = 0.004, p < 0.001). Figure 2 clarifies the functional form of the association between Trump votes and mask usage in Model 4. According to Figure 2, the positive association between Trump votes and infrequent mask usage is primarily observed in majority Trump counties or counties where Trump won over 60 percent of the vote in 2016.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted percentage of infrequent mask usage by percent Trump votes

Although our results are substantively identical across models, we observed considerable attenuation in the coefficient for percentage evangelical Christian from Models 2 to 4. In fact, controlling for Trump votes in Model 4 accounted for approximately 38 percent of the association between the percentage evangelical Christian and mask usage in Model 2 ([0.045–0.028]/0.045). In other words, over one‐third of the original association between Trump votes and mask usage was due to the fact that the percentage of evangelical Christian is positively associated with Trump votes.

Although we are not primarily interested in our background variables, we noted several statistically significant associations with mask usage. The percentage of infrequent mask usage tends to be lower in counties with more elderly residents, greater racial‐ethnic diversity, more college graduates, more unemployment, higher median incomes, and greater population density. We also observed that counties in states with Republican governors tended to exhibit a higher percentage of infrequent mask usage.

In supplemental analyses, we assessed the robustness of our regression results using different statistical procedures. More specifically, we replicated our reported WLS regression results using standard OLS regression and regression with clustered robust standard errors. All supplemental analyses are available upon request.

DISCUSSION

Although the CDC eventually recommended wearing masks or other protective face coverings in public to slow the spread of the coronavirus, the practice has been contentious and unevenly distributed in the population. In this article, we examined the association between various indicators of conservatism and mask usage at the county level. Our first hypothesis indicated that populations with larger percentages of votes for Trump in the 2016 presidential election would tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic. This hypothesis was generally supported in our analyses; however, the association was more complex than we expected. Essentially, the positive association between Trump votes and infrequent mask usage was nonlinear in the sense that it was only observed in majority Trump counties. In other words, each additional percentage of Trump support tended to increase the percentage of infrequent mask usage in counties where Trump earned over 60 percent of the vote. Notably, this pattern persisted with adjustments for percentage evangelical, Fox News interest, percentage aged 65 and older, racial‐ethnic diversity, percentage college‐educated, median income, the unemployment rate, population density, and governor's political party. Our findings are consistent with recent opinion polls and studies of political affiliation, political orientation, and risky pandemic lifestyles and behavioral intentions (Graham et al., 2020; Kramer, 2020; Perry, Whitehead, & Grubbs, 2020). To our knowledge, we are the first to have documented an association between Trump partisanship per se and mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic.

Our second hypothesis specified that populations with larger percentages of evangelical Christians would tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage. Although this hypothesis was supported, we noted considerable attenuation in the association between percentage evangelical and infrequent mask use when we adjusted for Trump votes. In this case, we interpret attenuation as mediation. The primary reason why evangelical counties are less likely to wear masks is because these counties also tend to follow the leadership of President Trump. The evangelical orientation of these counties was established long before Trump ran for political office. Evangelicals voted for Trump in 2016 to support various conservative Christian agendas (Gorski, 2019). Later, during the pandemic, evangelical counties were exposed to President Trump's ideological resistance to wearing masks. For the most part, these patterns dovetail with recent studies of general religiosity, Christian nationalism, and risky pandemic behaviors and lifestyles (Hill, Gonzalez, & Burdette, 2020; Perry, Whitehead, & Grubbs, 2020). However, we believe we are the first to have established an empirical link between evangelical populations and mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic.

Our final hypothesis suggested that populations with greater media interest in Fox News would tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage. This hypothesis was also supported by our analysis. Although we were unable to find any previous studies of Fox News interest and mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic, our results are generally consistent with previous research connecting Fox News consumption with perceived vulnerability to the coronavirus and endorsement of pandemic‐related misinformation and conspiracy theories (Calvillo et al., 2020; Motta, Stecula, & Farhart, 2020).

Taken together, our findings confirm the suspicion that populations with larger conservative populations are less likely to wear masks or other protective face coverings during the coronavirus pandemic. Given the effectiveness of masks in limiting the transmission of respiratory droplets, conservatism may indirectly support the acquisition and spread of the coronavirus. In the context of a pandemic, these risks are pervasive across political and religious spectrums. Because the coronavirus is a contagious infectious disease rather than a chronic disease that develops over the life course, systematic ideological resistance to public health recommendations is an immediate existential threat to society. In this light, we must begin to seriously think about ways to overcome widespread cultural barriers to critical pandemic responses. Potential strategies or interventions must address obstacles related to (1) denying health information from health scientists (mistrust of science), (2) accepting health misinformation from unqualified political and religious leaders (misguided authority), and (3) rejecting public health restrictions on individual behavior (violent individualism).

We acknowledge that our analyses are limited in four key respects. Although our data suggest that more conservative counties tend to exhibit lower rates of mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic, we cannot conclude that conservative individuals per se are less likely to wear mask. Because we are currently in the early stages of the pandemic, we are unable to assess concurrent changes in our predictor variables over time.

In terms of measurement, our mask usage data are limited in the sense that they are based on aggregated self‐reports of behavior, not actual behavior. Our Google Search Trends data should also be considered in the context of several drawbacks. First, Google Search Trends employs data collected from unique samples of Internet users who conduct searches on Google (Scheitle, 2011). To the extent that these data represent special populations (e.g., people who are younger and more socioeconomically advantaged), our analyses may systematically neglect some of the most conservative populations (e.g., people who are older and less educated). Second, Google Search Trends provides no information regarding motivations for any searches (Reyes, Majluf, & Ibáñez, 2018). While there are a number of potential reasons why someone might search for “Fox News” on Google, those motives are unspecified in the data. Finally, aggregate Internet search results from Google Search Trends may be impacted by changes in the search algorithm (Lazer et al., 2014). With all of this in mind, we note that our core findings are generally consistent with previous theoretical arguments concerning the pillars of conservatism and several empirical polls and studies conducted at the level of the individual. We are also encouraged by the fact that our mask reports are predictably associated with objective shelter‐in‐place data and other county‐level background variables.

Despite these limitations, we have provided the first empirical study of county‐level conservatism and mask usage during the coronavirus pandemic. Our analyses consistently showed that populations with greater support for President Trump, greater affiliation with evangelical Christianity, and greater interest in Fox News tend to exhibit higher rates of infrequent mask usage. Our analyses are important because they contribute to our understanding of the functional form and processes underlying the social patterning of mask usage, which is ultimately relevant to slowing the spread of the coronavirus. More research is needed to replicate our findings using longitudinal designs and data collected at different levels of analyses. As more valid and reliable epidemiological data become available, we will need to assess whether infection and mortality rates also vary according to indicators of conservatism. Future work should continue to consider the social patterning of mask usage more broadly, including understanding the role of conservatism as a moderator of other established predictors of mask usage. For example, we find that counties with more highly educated populations tend to exhibit lower rates of infrequent mask usage. Could this general pattern be attenuated by conservatism? Research along these lines would provide a more thorough understanding of the impact of social and ideological forces on pandemic health behavior and lifestyles.

Gonzalez, Kelsey E. , James, Rina , Bjorklund, Eric T. , and Hill Terrence D.. 2021. “Conservatism and Infrequent Mask Usage: A Study of US Counties During the Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic.” Social Science Quarterly 102:2368–2382. 10.1111/ssqu.13025

Footnotes

We are aware that there are longstanding state‐level measures of citizen and governmental political ideology (see Berry et al. 2010). To our knowledge, no such measure exists for counties. We have chosen to operationalize country‐level political conservatism through our three pillars of conservatism.

REFERENCES

- Aleem, Zeeshan . 2020. “A New Poll Shows a Startling Partisan Divide on the Dangers of the Coronavirus: Most Democrats are lot More Worried than Republicans.” Vox, March 15, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/3/15/21180506/coronavirus‐poll‐democrats‐republicans‐trump

- Bail, Christopher , Brown Taylor, and Wimmer Andreas. 2019. “Prestige, Proximity, and Prejudice: How Google Search Terms Diffuse Across the World.” American Journal of Sociology 124:1496–548. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, Zack . 2020. “The Deep Ideological Roots of Trump's Botched Coronavirus Response: How the GOP's Long War on Expertise Sabotaged America's Fight against the Pandemic.” Vox, March 17, 2020. https://www.vox.com/policy‐and‐politics/2020/3/17/21176737/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐trump‐response‐expertise

- Berry, William. D ., Fording Richard C., Ringquist Evan J., Hanson Russell L. and Klarner Carl E.. 2010. “Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the U.S. States: A Re‐Appraisal.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 10:117–35. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Peter . 1977. Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure (Vol. 7). New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolce, Louis , De Maio Gerald, and Muzzio Douglas. 1996. “Dial‐In Democracy: Talk Radio and the 1994 Election.” Political Science Quarterly 111:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bunch, Will . 2020. “GOP, Fox News have Waged War on Science. With Coronavirus, Will Their Aging Fans Pay the Price?” The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 15, 2020. https://www.inquirer.com/health/coronavirus/coronavirus-republicans-denial-fox-news-trump-war-on-science-20200315.html [Google Scholar]

- Burge, Ryan . 2020. White Evangelicals’ Coronavirus Concerns are Fading Faster. Christianity Today, June 23, 2020. https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2020/june/evangelicals‐covid‐19‐less‐worry‐social‐distancing‐masks.html [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, Dustin , Ross Bryan, Garcia Ryan, Smelter Thomas, and Rutchick Abraham. 2020. “Political Ideology Predicts Perceptions of the Threat of COVID‐19 (and Susceptibility to Fake News About It.).” Social Psychological and Personality Science 11:1119–28. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. How to Protect Yourself & Others . https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/prevent‐getting‐sick/prevention.html

- Collins, Michael , and Jackson David. 2020. Trump says CDC Director Robert Redfield ‘Confused’ about Coronavirus Vaccine, Mask Efficacy. USA TODAY, September 16, 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/09/16/trump‐cdc‐director‐robert‐redfield‐confused‐vaccine‐masks/5720828002/ [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus Resource Center . 2021. COVID‐19 Dashboard, Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University . https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Derysh, Igor . 2020. Fox News Hosts Downplay Surge in Coronavirus Cases, Dispute Science on Masks and Social Distancing. Salon, July 8, 2020. https://www.salon.com/2020/07/08/fox-news-hosts-downplay-surge-in-coronavirus-cases-dispute-science-on-masks-and-social-distancing/ [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher , Bartkowski John, and Segal Michelle. 1996. “Conservative Protestantism and the Parental Use of Corporal Punishment.” Social Forces 74:1003–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher , and Musick Marc. 1995. “Conservative Protestantism and Public Opinion toward Science.” Review of Religious Research 36:245–62. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John . 2013. “The Growing Social and Moral Conflict between Conservative Protestantism and Science.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52:368–85. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John , and Evans Michael. 2008. “Religion and Science: Beyond the Epistemological Conflict Narrative.” Annual Review of Sociology 34:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Lauren , Maibach Edward, Roser‐Renouf Connie, and Leiserowitz Anthony. 2012. “Climate on Cable: The Nature and Impact of Global Warming Coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 17:3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Lauren , Myers Teresa, Hmielowski Jay, and Leiserowitz Anthony. 2014. “The Mutual Reinforcement of Media Selectivity and Effects: Testing the Reinforcing Spirals Framework in the Context of Global Warming.” Journal of Communication 64:590–611. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, John . 2020. Freedom of Religion Doesn't Mean Freedom from Mask Mandates. Yahoo! News, August 20, 2020. https://news.yahoo.com/freedom‐religion‐doesn‐t‐mean‐103001188.html [Google Scholar]

- Foxnews.com . 2020a. “Does Wearing a Face Mask Pose any Health Risks?” Fox News, July 2, 2020. https://www.foxnews.com/health/does‐wearing‐a‐face‐mask‐pose‐any‐health‐risks

- Foxnews.com . 2020b. “Should we be Wearing Masks Everywhere, even at Home?” Fox News, August 12, 2020. https://video.foxnews.com/v/6180318434001#sp=show‐clips

- Frank, Thomas . 2007. What's the Matter with Kansas? New York: Henry Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Frankovic, Kathy . 2020. As Coronavirus Cases Increase, so does American Concern. YouGov, March 6, 2020. https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles‐reports/2020/03/06/coronavirus‐cases‐increase‐so‐does‐american‐concer [Google Scholar]

- Fritze, John . 2020. Trump: Won't Wear a Coronavirus Mask because it Would Interfere with Foreign Leader Meetings. USA TODAY, April 3, 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/04/03/coronavirus-trump-wont-wear-mask-because-foreign-leader-meetings/2945378001/ [Google Scholar]

- Funk, Cary , Hefferon Meg, Kennedy Brian, and Johnson Courtney. 2019. “Trust and Mistrust in Americans’ Views of Scientific Experts.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/08/02/trust-and-mistrust-in-americans-views-of-scientific-experts/ [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat, Gordon . 2008. “A Test of Three Theories of Anti‐Science Attitudes.” Sociological Focus 41:337–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat, Gordon . 2012. “Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010.” American Sociological Review 77:167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Jack , and Martin Walter. 1962. “Urbanization, Technology, and the Division of Labor: International Patterns.” American Sociological Review 27:667–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero , Correa Teresa, and Valenzuela Sebastian. 2012. “Selective Exposure to Cable News and Immigration in the U.S.: The Relationship Between FOX News, CNN, and Attitudes Toward Mexican Immigrants.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Google . 2020. Community Mobility Reports . https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

- Gorski, Philip . 2019. “Why Evangelicals Voted for Trump: A Critical Cultural Sociology.” In Politics of Meaning/Meaning of Politics: Cultural Sociology of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, edited by Mast J. L. and Alexander J. C., 165–183. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Amanda , Cullen Frank, Pickett Justin, Jonson Cheryl, Haner Murat, and Sloan Melissa. 2020. “Faith in Trump, Moral Foundations, and Social Distancing Defiance during the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Socius 6:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Grammich, Clifford , Hadaway Kirk, Houseal Richard, Jones Dale, Krindatch Alexei, Stanley Richie, and Richard Taylor. 2018. U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations and Membership Study, 2010 (State File; ). http://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/RCMSST10.asp [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, Andrew . 2020. 75% of Republicans Trust Trump's Medical Advice. YouGov, April 24, 2020. https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles‐reports/2020/04/24/75‐republicans‐trust‐trumps‐medical‐advice [Google Scholar]

- Grzeszczak, Jocelyn . 2020. Ohio Parents Say Masks in School Infringe on Religious Beliefs, Sue Health Director. Newsweek, September 15, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/ohio‐parents‐say‐masks‐school‐infringe‐religious‐beliefs‐sue‐health‐director‐1531994 [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Terrence , Gonzalez Kelsey, and Burdette Amy. 2020. “The Blood of Christ Compels Them: State Religiosity and State Population Mobility during the Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic.” Journal of Religion and Health 59:2229–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Terrence , Gonzalez Kelsey, and Davis Andrew. 2021. “The Nastiest Question: Does Population Mobility Vary by State Political Ideology during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic?” Sociological Perspectives. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0731121420979700 [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Terrence , Gonzalez Kelsey, and Upenieks Laura. 2021. “Love Thy Aged? A State‐Level Analysis of Religiosity and Mobility in Aging Populations during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic.” Journal of Aging and Health 33:377–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, Shanto , and Hahn Kyu. 2009. “Red Media, Blue Media: Evidence of Ideological Selectivity in Media Use.” Journal of Communication 59:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Stephanie . 2020. More Americans say they are Regularly Wearing Masks in Stores and other Businesses. Pew Research, August 27, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/27/more-americans-say-they-are-regularly-wearing-masks-in-stores-and-other-businesses/ [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, Jon , and MacInnis Bo. 2010. Frequent Viewers of Fox News Are Less Likely to Accept Scientists’ Views of Global Warming. Stanford, CA: The Woods Institute for the Environment. https://people.uwec.edu/jamelsem/papers/CC_Literature_Web_Share/Public_Opinion/CC_Fox_News_Krosnick_2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, Paul . 2020. What is it with Trump and Face Masks? New York Times, September 17, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/17/opinion/donald‐trump‐masks.html [Google Scholar]

- Kshetri, Nir , and Voas Jeffrey. 2017. “The Economics of ‘Fake News’.” IT Professional 19:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lazer, David , Kennedy Ryan, King Gary, and Vespignani Alessandro. 2014. “The Parable of Google Flu: Traps in Big Data Analysis.” Science 343:1203–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkley, Eric . 2020. Many Americans Deeply Distrust Experts. So Will They Ignore the Warnings About Coronavirus? The Washington Post, March 19, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/19/even-with-coronavirus-some-americans-deeply-distrust-experts-will-they-take-precautions/ [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Jonathan . 2005. “The Fox News Factor.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 10:56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult . 2020. “Morning Consult's Governor Approval Rankings.” Accessed on 5/1/2020. https://morningconsult.com/governor-rankings/

- Motta, Matthew . 2018a. “The Polarizing Effect of the March for Science on Attitudes toward Scientists.” Political Science & Politics 51:782–8. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Matthew . 2018b. “The Dynamics and Political Implications of Anti‐Intellectualism in the United States.” American Politics Research 46:465–98. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Matt , Stecula Dominik, and Farhart Christina. 2020. “How Right‐Leaning Media Coverage of COVID‐19 Facilitated the Spread of Misinformation in the Early Stages of the Pandemic in the U.S.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 53:335–42. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, Vidya , Barash Vlad, Kelly John, Kollanyi Bence, Neudert Lisa‐Marie, and Howard Philip. 2018. “Polarization, Partisanship and Junk News Consumption over Social Media in the Us.” https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.01845

- National Governors Association . 2020. Governors . https://www.nga.org/governors/

- Naylor, Brian , and Wise Alana. 2020. Contradicting The CDC, Trump Says COVID‐19 Vaccine could be Ready by End of Year. NPR, September 16, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/09/16/913560563/cdc-director-says-covid-vaccine-likely-wont-be-widely-available-until-next-year [Google Scholar]

- Oreskes, Naomi , and Conway Erik. 2010. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscure the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Climate Change. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parke, Caleb . 2020. “Dr. Siegel Tells Tucker Carlson there is ‘No Science’ behind Biden's Mask Mandate Siegel called it ‘The Politics of Fear.” Foxnews.com, August 14. https://www.foxnews.com/politics/biden‐mask‐mandate‐tucker‐carlson‐doctor‐siegel‐saphier

- Perry, Samuel , Whitehead Andrew, and Grubbs Joshua. 2020. “Culture Wars and COVID‐19 Conduct: Christian Nationalism, Religiosity, and Americans’ Behavior during the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59:405–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pinckard, Cliff . 2020. “Ohio Legislator Cites God for Refusing to Wear Face Mask during Coronavirus Crisis.” Cleveland.com, May 6, 2020. https://www.cleveland.com/coronavirus/2020/05/ohio-legislator-cites-god-for-refusing-to-wear-face-mask-during-coronavirus-crisis.html

- Porter, Tom . 2020. Tucker Carlson said Mask‐Wearing has ‘No Basis of any Kind in Science,’ Reversing an Earlier Position that they are Obviously Effective. Business Insider, July 8. https://www.businessinsider.com/tucker-carlson-no-basis-in-science-for-masks-contradicts-old-stance-2020-7 [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Tomas , Majluf Nicolás, and Ibáñez Ricardo. 2018. “Using Internet Search Data to Measure Changes in Social Perceptions: A Methodology and an Application.” Social Science Quarterly 99:829–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Linley . 2020. Most Americans are Worried about COVID‐19—but not Republicans. Yahoo News/YouGov, March 12, 2020. https://today.yougov.com/topics/health/articles‐reports/2020/03/12/coronavirus‐data‐poll [Google Scholar]

- Scheitle, Christopher . 2011. “Google's Insights for Search: A Note Evaluating the Use of Search Engine Data in Social Research.” Social Science Quarterly 92:285–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, Hana , MacKendrick Norah, and Mora G. Cristina. 2020. “Pandemic Politics: Political Worldviews and COVID‐19 Beliefs and Practices in an Unsettled Time.” Socius 6:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat, Darren , and Ellison Christopher. 2007. “Structuring the Religion‐Environment Connection: Identifying Religious Influences on Environmental Concern and Activism.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shugerman, Emily . 2018. Trump Supporters Trust the President More Than Their Family and Friends, Poll Finds. Independent, August 2, 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-family-friends-approval-rating-poll-supporters-fans-republicans-a8472111.html. [Google Scholar]

- Smiley, Kevin . 2019. “A Polluting Creed: Religion and Environmental Inequality in the United States.” Sociological Perspectives 62:980–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Savannah . 2020. Unmasked: How Trump's Mixed Messaging on Face‐Coverings Hurt U.S. Coronavirus Response. nbcnews.com, August 9, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/calendar-confusion-february-august-trump-s-mixed-messages-masks-n1236088 [Google Scholar]

- Stanley‐Becker, Isaac . 2020. As Trump Signals Readiness to Break with Experts, His Online Base Assails Fauci. The Washington Post, March 26, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/as-trump-signals-readiness-to-break-with-experts-his-online-base-assails-fauci/2020/03/26/3802de14-6df6-11ea-aa80-c2470c6b2034_story.html [Google Scholar]

- Stephens‐Davidowitz, Seth . 2014. “The Cost of Racial Animus on a Black Candidate: Evidence Using Google Search Data.” Journal of Public Economics 118:26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini . 2008. “Media Use and Political Predispositions: Revisiting the Concept of Selective Exposure.” Political Behavior 30:341–66. [Google Scholar]

- Swearingen, C ., and Ripberger Joseph. 2014. “Google Insights and U.S. Senate Elections: Does Search Traffic Provide a Valid Measure of Public Attention to Political Candidates?” Social Science Quarterly 95:882–93. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times . 2020. Mask‐Wearing Survey Data . github.com/nytimes/covid‐19‐data/tree/master/mask‐use

- US Census Bureau . 2019. 2014‐2018 American Community Survey 5‐Year Estimates . https://www.census.gov/programs‐surveys/acs/technical‐documentation/table‐and‐geography‐changes/2018/5‐year.html

- Van Bavel, Jay . 2020. In a Pandemic, Political Polarization could Kill People. The Washington Post, March 22, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/23/coronavirus‐polarization‐political‐exaggeration/ [Google Scholar]

- Vojak, Brittany . 2018. “Fake News: The Commoditization of Internet Speech.” California Western International Law Journal 48:36. [Google Scholar]