Abstract

Effective vaccines are essential for controlling the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. CoronaVac, which is an inactivated virus vaccine, was the first imported COVID‐19 vaccine in Thailand. To investigate the safety and immunogenicity of CoronaVac within the Thai population, we conducted a prospective cohort study among health care workers aged 18–59 years, who received a 2‐dose regimen of CoronaVac 21 days apart between March and April 2021 at the hospital in Samut Sakhon, Thailand. We recruited 185 participants with a mean age of 32 years. Total antibodies against receptor‐binding domain (RBD) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) against nucleocapsid (N) protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 were tested. Total antibodies against RBD were negative before immunization. One volunteer was positive for N, although negative for the RBD antibodies. The seroconversion rate of total antibodies against RBD after the first CoronaVac dose was 67% with a Geometric mean concentration (GMC) of 1.98 U/ml. Following CoronaVac dose 2, the seroconversion rate increased to 100% with a GMC of 92.9 U/ml. The seroconversion rates of IgG against N protein were 1% after dose 1 and 62.8% after dose 2. The overall incidence of adverse reactions was 59.5%. Injection‐site pain was the most common local adverse event (52.4%), while myalgia was the most common systemic adverse event (31.9%). No serious adverse events were observed. A 0–21 days, 2‐dose CoronaVac regimen appears safe, inducing a satisfactory response compared with convalescent serum obtained 4–6 weeks postnatural infection. Antibody responses after 2‐dose CoronaVac were comparable to the convalescent plasma but waned rapidly after 3 months. Therefore, we recommend 2‐dose CoronaVac administration with possible booster doses.

Keywords: COVID‐19, immunogenicity, inactivated vaccine, nucleocapsid protein, RBD, safety, spike protein

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus (SARS‐CoV‐2), which spread rapidly, reaching pandemic status and presenting high morbidity and mortality in March 2020. 1 As of September 2021, SARS‐CoV‐2 has infected more than 230 million people worldwide, resulting in over 4 million deaths. 2 Moreover, COVID‐19 has had adverse global impacts on education, 3 psychosocial well‐being, 4 and economies. 5

Given the need for a robust and enduring immune response to fight with this virus, an effective vaccine is an essential strategy for controlling the COVID‐19 pandemic. As of September 2021, there were 315 candidate vaccines, of which 194 and 121 vaccines were, respectively, in the preclinical and clinical phases. Candidate vaccines in the clinical phase are being developed using different platforms: inactivated virus, live‐attenuated virus, protein subunits, virus‐like particles, DNA, RNA, viral vectors, and viral vectors with antigen‐presenting cells. 6 As of June 2021, World Health Organization (WHO) has approved six COVID‐19 vaccines which met the criteria for safety and efficacy: CoronaVac, BBIBP‐CorV, Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Johnson and Johnson and Oxford/AstraZeneca. 7

SARS‐CoV‐2 has four key structural proteins: nucleocapsid (N) protein in the ribonucleoprotein core; and the spike (S) protein, matrix (M) protein, and envelope (E) protein embedded on the viral surface. 8 The S protein is the primary target antigen for COVID‐19 vaccine development. Antibodies against the S protein, especially the receptor‐binding domain (RBD) epitope, are essential for preventing the virus from entering target cells. Moreover, S protein has been identified as a significant inducer of protective immunity against SARS‐CoV‐2. N protein is highly immunogenic and induces a robust humoral and cellular immune response. 9 , 10

Inactivated vaccines are whole virus preparations that are chemically‐inactivated with beta‐propiolactone and formaldehyde. 11 Although they are no longer replication‐competent, virus integrity is preserved, serving as an immunogen that is S‐specific, RBD‐specific and N‐specific. 8 Studies have shown that inactivated vaccines have favorable safety profiles in various populations and can induce antibody responses. 12 , 13 CoronaVac, also known as the CoronaVac vaccine, is an inactivated vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2 which is propagated in cell culture before being inactivated, concentrated, purified and adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide. CoronaVac is developed by Sinovac Life Sciences. 14 The results of a preclinical study showed that CoronaVac effectively induced neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in animals and provided partial or complete protection in macaques following a SARS‐CoV‐2 challenge. 15 However, inactivated vaccines are whole virus preparations that can induce non‐neutralizing antibodies, which might contribute to antibody‐dependent enhancement and disease severity. 16 Nonetheless, some studies have failed to find evidence of antibody‐dependent enhancement in animal models after CoronaVac. 15 Safety and immunogenicity profiles in phase 1/2 trials showed that this vaccine was well‐tolerated and induced a moderate immunogenic response in healthy adults. 12 Randomized controlled trials of CoronaVac in a phase III study showed efficacy 83.5% against symptomatic disease with a good safety profile. 17 However, many issues regarding vaccine performance remain unclear, including vaccination dosing intervals that differ from those used in the original trial and the duration of protection in real‐world conditions. Longitudinal studies are thus required to determine the duration of protective immunity.

In Thailand, CoronaVac, which was the first vaccine imported for controlling the COVID‐19 outbreak, was approved for emergency use in February 2021, 18 and the vaccination program commenced on February 28, 2021. This study aims to investigate the safety and immunogenicity of CoronaVac within the Thai population.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Methods

We conducted a prospective longitudinal cohort study at the Banphaeo General Hospital (BGH) in Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand. Ethical approval was obtained from BGH's institutional review board (Human Rights and Ethics Committee) (No. 2/2564). Written informed consent was also obtained from all participants. Demographic information and blood samples were compiled by registered nurses in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Practice Guideline (ICH‐GCP). The study was registered in the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20210308003).

2.2. Participants

The participants, who were health care workers (HCWs) at BGH aged between 18 and 59 years, received a 2‐dose regimen of CoronaVac, with a 3‐week interval between doses (0–21‐day schedule). The study's exclusion criteria were a previous diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, a known allergy to any vaccine components, underlying allergic diseases, a diagnosis of an immunocompromising or immunodeficiency disorder, treatment with immunosuppressive therapy, cancer, or an uncontrolled chronic medical condition. Participants who were pregnant or breastfeeding were also excluded from this study.

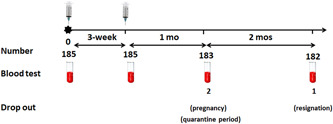

Participants’ demographic data, namely their age, sex, occupation, and comorbidities were recorded. Moreover, we measured baseline antibodies against RBD and N protein immediately before vaccination in all of the enrolled participants to determine baseline SARS‐CoV‐2 serostatus. Assessments of the immunogenicity of CoronaVac, total antibodies against RBD, and Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against N protein, which were primary study outcomes, were performed 3 weeks after dose 1, and 1 and 3 months after dose 2 (Figure 1). Levels of antibodies obtained using samples of convalescent serum collected 4–6 weeks after a natural infection from infected COVID‐19 patients of the previous study 19 were measured and concentrations of antibodies were compared with those obtained from the vaccine‐induced immune response. The secondary outcome comprised assessments of local adverse reactions to the vaccine (e.g., pain, swelling, and redness) or systemic adverse events (e.g., fever, allergic reactions, headaches, and myalgia) recorded by the participants over a 7‐day period after each vaccination.

Figure 1.

A diagrammatic depiction of the study design

2.3. Vaccine

CoronaVac (Sinovac Life Sciences) is an inactivated virus vaccine created from African green monkey kidney cells (Vero cells) that have been inoculated with SARS‐CoV‐2 (CZ02 strain). At the end of the incubation period, the virus was harvested, inactivated with β‐propiolactone and formaldehyde, concentrated, purified, and finally absorbed onto aluminium hydroxide. The aluminium hydroxide complex was then diluted in a sodium chloride, phosphate‐buffered saline, and water solution before being sterilized and filtered ready for injection. Each vial contains 0.5 ml with 600 Spike Unit (equal to 3 μg) of inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 whole‐virion as antigen. 12 , 14

2.4. Total antibodies against RBD

Serum samples from all of the participants were tested for total antibodies against RBD. Measurements of total antibodies (predominantly IgG, but also IgA and IgM) against the RBD were obtained from electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, Roche Elecsys Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 S (Cat. No. 09289267190; Roche). These kits used a Wild‐type or Wuhan strain as an antigen. The positive cut‐off level was ≥0.80 U/ml and the upper limit was 250 U/ml. If the total antibodies against RBD exceeded the upper reading limit (250 U/ml), serum samples were diluted to obtain values within a detectable range.

2.5. IgG antibodies against nucleocapsid (N) protein

Measurements of IgG antibodies against N protein were carried out using the chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technique, SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG (Cat. No. 6R86‐20; Abbott Diagnostics). These kits also used a Wild‐type or Wuhan strain as an antigen. A nucleocapsid IgG level index of signal/cut‐off (S/C) ≥1.4 was considered a positive result. Both tests (total RBD antibodies and anti‐N IgG) were the available tests during the study period.

2.6. Statistical analysis

We calculated a sample size of 75 individuals based on 95% CoronaVac seroconversions obtained in a previous study. 20 Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.1.0). Correlation between age and total antibodies against RBD and IgG against N protein were assessed with Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. The seroconversion rates of total antibodies against RBD and IgG against N protein were calculated as percentages. We calculated the geometric mean concentration (GMC) and associated 95% confidence interval (CI). The Wilcoxon matched pairs signed test was performed to compare antibodies each blood sampling within the same participant. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare antibodies between blood sampling of participants and convalescent serum. Safety analyses were presented as numbers and percentages of participants experiencing local and systemic adverse events. A two‐tailed p value of 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

We performed this study between March 1, 2021 and June 25, 2021 with a sample of 185 participants (83.2% women), whose mean age was 32.1 ± 8.7 years (a median age of 30 years) (interquartile range [IQR]: 25–37). The participants’ mean body‐mass index was 22.6 ± 3.8 kg/m2. A total of 15 (8.1%) participants had comorbidities, namely hypertension (2.2%), dyslipidemia (1.6%), thyroid disease (1.1%), and other conditions (3.2%). None of the participants had underlying diabetes, heart disease, or chronic kidney disease (Table 1). Two participants dropped out of the study before the third blood sampling stage; one was pregnant and the other was quarantined. One participant resigned and therefore dropped out at the time of the fourth blood sampling.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

| Variables | HCW (n = 185) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 154 (83.2) |

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 32.1 (8.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (SD) | 22.6 (3.8) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 15 (8.1) |

| Hypertension | 4 (2.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (1.6) |

| Thyroid disease | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 6 (3.2) |

| Occupations, n (%) | |

| Doctor | 26 (14) |

| Nurse | 61 (33) |

| Paramedical staff | 39 (21.1) |

| Nonparamedical staff | 59 (31.9) |

Note: The data are presented as N (%) or mean (SD) values.

Abbreviations: BMI, body‐mass index; HCW, health care worker.

3.1. Immunogenicity

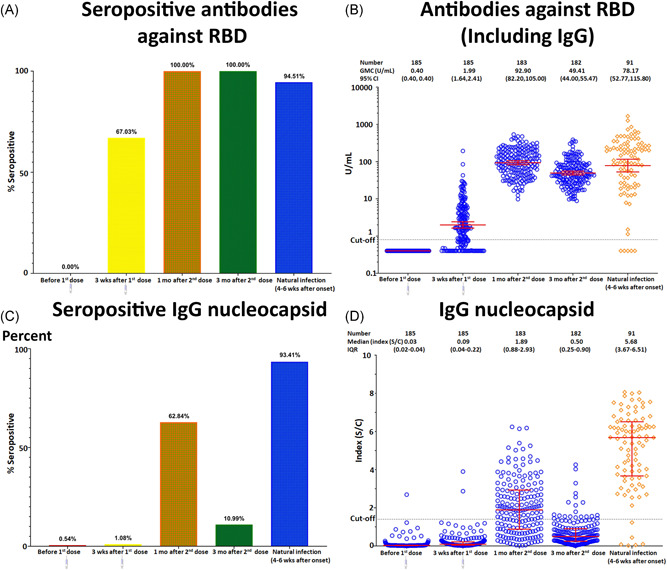

Only 1 participant had a measurable IgG against N protein of 2.69 index (S/C) at the baseline. However, this individual tested negative for total antibodies against RBD. Total antibodies against RBD seroconverted in 124 out of the 185 participants (67%) after dose 1 and in 183 out of 183 participants (100%) a month after full vaccination (Figure 2A). The seroconversion rates after dose 1 and dose 2 were significantly different (p < 0.01)

Figure 2.

Comparison of antibodies against RBD and IgG antibodies against N protein at the baseline and after each CoronaVac injection with convalescent serum from recovered COVID‐19 patients: seroconversion rate (A, C) and titer level (B, D). The red lines indicate GMC and 95% CI values. CI, confidence interval; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; GMC, geometric mean concentration; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; RBD, receptor‐binding domain

After the administration of doses 1 and 2, the GMC (95% CI) for total antibodies against RBD were 1.99 (1.64, 2.41) U/ml and 92.9 (82.2, 105) U/ml, respectively. The level thus increased significantly between doses 1 and 2, p < 0.01. The seroconversion rate of antibodies against RBD remained 100% positive 3 months after immunization. However, the GMC (95% CI) decreased to 49.4 (44.00, 55.47) U/ml (Figure 2B). These antibodies consistently increased in 15 subjects between the first‐ and third‐month following immunizations, with elevated levels ranging from 1.1 to 4.7 times. However, the level of antibodies against N protein did not increase in these participants.

Nucleocapsid IgG antibody seroconversion occurred in 2 out of 185 participants (1%) after dose 1 and in 115 out of 183 participants (62.84%) a month after full vaccination (Figure 2C). After doses 1 and 2 of vaccine had been administered, the median (IQR) for IgG against N protein S/C index were 0.09 (0.04–0.22) and 1.89 (0.88–2.93), respectively. The antibodies increased significantly between doses 1 and 2 (p < 0.01). Three months after completion of the 2‐dose immunization regimen, the seroconversion rate of IgG against N protein had decreased to 10.99%, and all of the subjects’ antibodies had declined (the median [IQR] of S/C index was 0.50 [0.25–0.90]) (Figure 2D).

We compared the immune response to the CoronaVac vaccination to data on levels of 91 convalescent serum samples obtained from previously PCR‐confirmed COVID‐19 patients of the previous study. Total antibodies against RBD, with a GMC with 95% CI value of 78.17 U/ml (52.77,115.8) and N protein, with a median (IQR) S/C index of 5.68 (3.67,6.51) were produced during natural infection. One month after full vaccination, the serum of participants had higher but statistically nonsignificant (p < 0.3) antibody levels against RBD compared with the convalescent serum (GMC [95% CI], 92.9 [82.20, 105.0] vs. 78.17 [52.77, 115.8] U/ml). However, IgG against N protein levels in these participants were significantly lower than those in convalescent serum (S/C index 1.89 [0.88,2.93] vs. 5.68 [3.67,6.51]; p < 0.01).

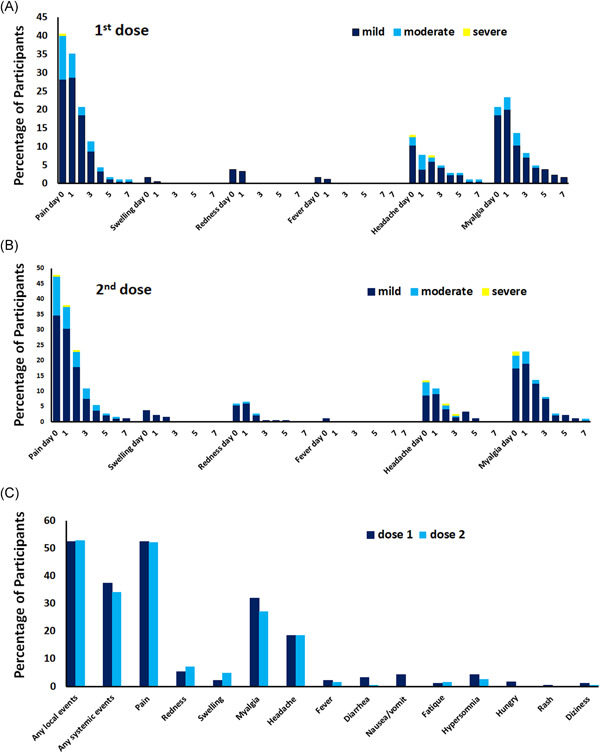

3.2. Safety

The overall incidence of adverse reactions to the CoronaVac vaccines was 59.5%. Local adverse events occurred more frequently than systemic adverse events after the first dose (52.4% vs. 37.3%) and the second dose (52.7% vs. 34.2%). The proportions of participants reporting local and systemic reactions were similar for each dose. Most of the adverse events were mild to moderate in severity. The most common adverse event was injection‐site pain, which was reported by 52.4% after the first dose, with a similar percentage after the second dose by 52.2%. The pain, mostly of mild severity, generally commenced after the injection and resolved within a few days. Redness and swelling were reported in a lower percentage of participants. The most frequently reported systemic adverse events after the first and second doses were myalgia (31.9% vs. 27.2%), headaches (18.4% vs. 18.5%), and fever (2.2% vs. 1.6%), respectively (Figure 3). Other side effects included nausea, diarrhea, hypersomnia, fatigue, hunger, a rash, and dizziness. No cases of serious adverse events or anaphylaxis occurred.

Figure 3.

Vaccine‐related local and systemic adverse events reported up to Day 7 following the administration of the first and second doses of CoronaVac

Age negatively correlated with total antibodies against RBD (correlation coefficient, −0.26; p < 0.001) and IgG against N protein (correlation coefficient −0.21; p < 0.004) 1 month after full vaccination. Comparisons of participants by sex and occupation did not reveal any significant differences in total antibodies against RBD and IgG against N protein at all timepoints tested.

4. DISCUSSION

In Thailand, CoronaVac and Oxford‐AstraZeneca 21 are the 2 primary COVID‐19 vaccines approved by the Thai Food and Drug Administration in February and March 2021, respectively. CoronaVac was the first vaccine to be imported to control the COVID‐19 outbreak among HCWs and high‐risk groups aged 18–59 years, and its implementation commenced in late February of 2021.

We found that 2 CoronaVac doses administered 3 weeks apart were safe and induced a satisfactory response. This CoronaVac regimen induced immunization against RBD comparable to levels induced after natural infection. However, compared with natural immunity postinfection, it induced a weak response to N protein. Age negatively correlated with total antibodies against RBD which is consistent with Pfizer‐BioNTech and Moderna. 22

In this study, CoronaVac was found to be safe regarding both local and systemic adverse events. Another COVID‐19 vaccine platform entails a similar issue. 23 , 24 , 25 However, participants who received CoronaVac, reported lower incidences of fever (1.6%–2.2%) compared with those who received other COVID‐19 vaccinations, such as the messenger RNA (mRNA)‐based Pfizer (1%–16%), Moderna (0.8%–15.5%) vaccines and the Oxford‐AstraZeneca viral vector vaccine (0%–24%). 23 , 24 , 25

Seropositivity rate for total antibodies against RBD in our study 21 days after dose 1 vaccination was 67%, which was lower than the rates reported for Pfizer‐BioNTech 99.5% and Oxford‐AstraZeneca 97.1% vaccines >14 days after dose 1. 26 The seroconversion rates in our study (100%) reached 1 month after dose 2 were higher than those previously reported for CoronaVac (95.6%–99.2%). 12 Total antibodies against RBD in our study at 1 month after dose 2 vaccination were lower than that induced by Pfizer‐BioNTech (1108 U/ml [95% CI: 1049–1170] and Moderna (2881 U/ml [95% CI: 2721–3051] at 6–10 weeks after dose 2. 22

Although the WHO has adopted the International Standard for anti SARS‐CoV‐2 immunoglobulins, the comparison of assays can be used for detection of the same class of immunoglobulins with the same specificity. Our total antibody assay (Roche) measured predominantly IgG, but also IgA and IgM against the RBD. To date, there was no standardized unit for measurement of total binding antibody. However, these comparisons should be interpreted carefully due to different population features, geographical regions, local circulation of the virus (including variants), and lack of unit standardization across the different antibody tests. 12 , 27 Thus, an immunological correlate of a potential protective threshold against SARS‐CoV‐2 remains unclear. Levels of antibodies against RBD after full vaccination obtained in our study were comparable with antibody titers obtained from recovered COVID‐19 patients. Previous studies with nonhuman primates support the use of convalescent serum from rhesus macaques 28 and postimmunization antibody titers for estimating a protection correlate for COVID‐19 vaccines. 28 , 29 Kristen et al. 30 found a strong correlation between antibody titers and vaccine efficacy across seven different vaccine platforms. Although we did not investigate neutralizing antibodies, previous studies showed that antibody levels against RBD were correlated with neutralizing antibody responses. 12 , 31 , 32

IgG against N protein induced by CoronaVac were lower than those elicited by natural infection. Previous study found that N‐specific IgG was abundant in the serum of COVID‐19 patients. 33 IgG antibodies against N protein proliferated 33 and then gradually decreased over time after natural infection. 34 Only 15 participants in our study had increased levels of antibodies against RBD 3 months postvaccination, whereas antibodies against N protein did not increase. This result suggests that the rise in the titer was induced by vaccination and not by natural infection. Inactivated vaccines induce antibodies against N protein, whereas virus vectors and mRNA do not. 8 Role of antibodies against N protein in immunized human needs to be further investigated.

However, the declines in the seroconversion rate and in the level of IgG antibodies against N protein in our study 3 months postvaccination were greater than that of antibodies against RBD, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study. 31 , 35 This result may be attributed to the lower half‐life of nucleocapsid antibodies compared with that of antibodies against RBD in natural infection. 36 Thus, antibody response may temporarily increase and then decline over time, and booster vaccines may be required.

There are some limitations in our study. Our examination of immunogenicity was confined to humoral immunity and did not include cellular mediated immunity. Additionally, the neutralizing capacities and the quality of the antibody responses induced by this vaccination were not assessed.

These data may not be generalizable to individuals with comorbidities or allergies. Nevertheless, we hope that our findings will inform future vaccination policies or strategies to control the COVID‐19 pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Ethic committee of the Institutional Review Board of BGH (No. 2/2564), and written inform consent was obtained from all participants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yong Poovorawan: as the principle investigator, designed this study, reviewed and edited the manuscript. Saovanee Benjamanukul and Sasiwimon Traiyan: wrote the first draft, formulated idea, performed statistical analysis, and provided the critical comment. Ritthideach Yorsaeng: performed data analysis and data visualization. Preeyaporn Vichaiwattana: performed experiments. Natthinee Sudhinaraset and Nasamon Wanlapakorn: provided stylistic revisions to manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Patcharee Kiatsermsakul, who facilitated data collection and to Miss Sirinthip Nimitphuwadon and Miss Jantakan Leauchom, the nurses and all participating staff at Banphaeo General Hospital who assisted in this project. We thank the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Center of Excellence in Clinical Virology, Chulalongkorn University and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital for supporting this study.

Benjamanukul S, Traiyan S, Yorsaeng R, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of inactivated COVID‐19 vaccine in health care workers. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1442‐1449. 10.1002/jmv.27458

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The supporting data are available within the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero‐Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470‐1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . WHO coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) dashboard. 2021. Updated September 24, 2021. Accessed September 26, 2021. http://covid19.who.int/

- 3. Al Samaraee A. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on medical education. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(7):1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedrosa AL, Bitencourt L, Fróes ACF, et al. Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verschuur J, Koks EE, Hall JW. Observed impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on global trade. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(3):305‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Draft landscape of COVID‐19 candidate vaccines. Updated September 2021. Accessed September 2 6,2021 http://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines

- 7. World Health Organization . COVID‐19 advice for the public: Getting vaccinated. Accessed September 18 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice

- 8. Dai L, Gao GF. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID‐19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(2):73‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee P, Kim CU, Seo SH, Kim DJ. Current status of COVID‐19 vaccine development: focusing on antigen design and clinical trials on later stages. Immune Netw. 2021;21(1):e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dagotto G, Yu J, Barouch DH. Approaches and challenges in SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28(3):364‐370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alderson J, Batchelor V, O'Hanlon M, Cifuentes L, Richter FC, Kopycinski J. Overview of approved and upcoming vaccines for SARS‐CoV‐2: a living review. Oxf Open Immunol. 2021;2(1):iqab010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18‐59 years: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):181‐192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu Z, Hu Y, Xu M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy adults aged 60 years and older: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):803‐812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Covid‐19 vero cell inactivated. Accessed September 26 2021. https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/COR-WHO-Adu-40_vials-insert.pdf

- 15. Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS‐CoV‐2. Science. 2020;369(6499):77‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee WS, Wheatley AK, Kent SJ, DeKosky BJ. Antibody‐dependent enhancement and SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines and therapies. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(10):1185‐1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanriover MD, Doğanay HL, Akova M, et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole‐virion SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398(10296):213‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food and Drug Administration, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Details of Medicinal Product. Accessed September 26 2021. https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/SINOVAC_TAG_PEG_REPORT_EUL-Final28june2021.pdf

- 19. Chansaenroj J, Yorsaeng R, Posuwan N, et al. Detection of SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific antibodies via rapid diagnostic immunoassays in COVID‐19 patients. Virol J. 2021;18(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xia S, Duan K, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of an inactivated vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2 on safety and immunogenicity outcomes: interim analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2020;324(10):951‐960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marsh GA, McAuley AJ, Au GG, et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 (AZD1222) vaccine candidate significantly reduces SARS‐CoV‐2 shedding in ferrets. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steensels D, Pierlet N, Penders J, Mesotten D, Heylen L. Comparison of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody response following vaccination with BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273. JAMA. 2021;326:1533‐1535 e2115125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccine administered in a prime‐boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single‐blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):1979‐1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid‐19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603‐2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eyre DW, Lumley SF, Wei J, et al. Quantitative SARS‐CoV‐2 anti‐spike responses to Pfizer‐BioNTech and Oxford‐AstraZeneca vaccines by previous infection status. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bayram A, Demirbakan H, Günel Karadeniz P, Erdoğan M, Koçer I. Quantitation of antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein after two doses of CoronaVac in healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2021;93(9):5560‐5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McMahan K, Yu J, Mercado NB, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS‐CoV‐2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2021;590(7847):630‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lumley SF, O'Donnell D, Stoesser NE, et al. Antibody status and incidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):533‐540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Earle KA, Ambrosino DM, Fiore‐Gartland A, et al. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID‐19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2021;39(32):4423‐4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marot S, Malet I, Leducq V, et al. Rapid decline of neutralizing antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 among infected healthcare workers. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Post N, Eddy D, Huntley C, et al. Antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in humans: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu L, Liu W, Zheng Y, et al. A preliminary study on serological assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) in 238 admitted hospital patients. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(4):206‐211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Noh JY, Kwak JE, Yang JS, et al. Longitudinal assessment of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 immune responses for six months based on the clinical severity of COVID‐19. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:754‐763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gallais F, Gantner P, Bruel T, et al. Evolution of antibody responses up to 13 months after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and risk of reinfection. EBioMedicine. 2021;71:103561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, et al. Immunological memory to SARS‐CoV‐2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371(6529):eabf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data are available within the article.