Abstract

Objective

We investigate how beliefs about scientists and presidents affect views about two pandemics, Zika virus (2016) and COVID‐19 (2020).

Methods

Three New Hampshire surveys in 2016 and 2020 provide data to test how beliefs about scientists’ practices and presidential approval relate to pandemic views.

Results

Support for presidents consistently predicts perceptions of scientists’ integrity and trust in science agencies for information, but the directionality changes from 2016 to 2020—increased trust among Obama‐supporters; decreased trust among Trump‐supporters. Respondents who believe scientists lack objectivity are also less likely to trust science agencies during both Zika and COVID‐19 and are less apt to be confident in the government's response in 2016. Assessments of pandemic responses become increasingly political during 2020; most notably, support for President Trump strongly predicts confidence in the government's efforts.

Conclusion

Results highlight how beliefs about scientists’ practices and presidents are central to the science–politics nexus during pandemics.

PANDEMICS AND THE ENTANGLING OF SCIENCE AND POLITICS

The prominent role scientists play in social life has never been more evident than during the new coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2 / COVID‐19) pandemic. From the outset, health scientists mobilized to investigate threats from COVID‐19 and provided recommendations to inform governmental responses (Chugh et al. 2020; Ghebreyesus and Swaminathan 2020). As the virus spread, physicians and scientists not only advised policymakers, but they also appeared in the media, where the public looked to them for understanding about both virus‐related risks and appropriate mitigating behaviors. While the visibility of scientists during the COVID‐19 outbreak is notable, they have long provided guidance to both health authorities and the public during pandemics such as Ebola, H1N1 (swine flu), severe acute respiratory syndrome, and Zika virus (Anderson et al. 2004; Bouzid et al. 2016: Chan et al. 2018; Klemm, Das, and Hartmann 2016).

Government officials working to combat the spread of COVID‐19 drew from past experiences with health‐related messaging during pandemics that underscored the importance of the public's trust in information providers in shaping understanding of risks and compliance with public health recommendations (Cairns, De Andrade, and MacDonald 2013; Dryhurst et al. 2020; van Baalen and van Fenema 2009; Siegrist and Zingg 2014). “Follow the science” became central to pandemic messaging as many believed that conveying to the public that responses to the new coronavirus were adhering to scientists’ recommendations would instill confidence. In early 2020 as COVID‐19 emerged, significant majorities of the U.S. public supported health scientists leading responses to the pandemic and were in favor of virus mitigating policies (McFadden et al. ). Nonetheless, as uncertainty about COVID‐19 continued, and some science‐based public health recommendations had negative economic effects or conflicted with core values such as personal freedom, scrutiny of the scientific community intensified. Some questioned scientists’ leadership within pandemic‐related policy making and the discourse surrounding the pandemic increasingly became politicized. In the wake of these trends, many looked to politicians rather than scientists for leadership regarding the virus.

Wide‐ranging social factors shape public perceptions of science and beliefs about scientists can influence assessments of risks as well as governmental actions focused on science‐related concerns (Brewer and Ley 2012; Gauchat 2012, 2015; Motta 2018a; Safford and Hamilton 2020; Safford, Hamilton, and Whitmore 2017; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2020, 2021; Renn and Levine 1991). In the case of COVID‐19, trust in science has been connected to compliance with virus control measures such as social distancing and masking as well as vaccine use (Dohle, Wingen, and Schreiber 2020; Fazio et al. 2021; Kazemian, Fuller, and Algara 2021; Latkin et al. 2021; Plohl and Musil 2021). What is less clear is how beliefs about the practice of science affect pandemic‐related views, to what extent such beliefs have shifted during COVID‐19, and how support for former U.S. President Donald Trump may connect to perceptions of scientists’ integrity, trust in science agencies for guidance, and confidence in the U.S. Government's COVID‐19 response.

We seek to expand knowledge on these topics, first, asking how, if at all, general beliefs about scientists’ objectivity in their methodological practices, and the social bases of those beliefs, may have changed during the time of COVID‐19. We then consider whether perceptions of scientists’ integrity, along with other key factors such as approval of political leaders, affect trust in science agencies as sources for virus‐related information and confidence in the federal government's responses to different pandemics. To answer these questions, we utilize data from public polls conducted in the U.S. state of New Hampshire during the 2016 Zika virus pandemic as well as the 2020 COVID‐19 crisis. These surveys include questions that query beliefs about scientists’ practices, trust in health science agencies, and confidence in the government's response to these pandemics. While these data are limited to one state, and should not be over‐generalized, they offer an informative longitudinal perspective on how the public perceives scientists’ integrity, and as these polls contain questions about approval of former Presidents Barak Obama and Donald Trump, they enable assessment of how confidence in these leaders relates to pandemic views.

Our analyses confirm that the questioning of scientists’ objectivity began well before the era of COVID‐19 and that beliefs about scientists’ integrity strongly relate to trust in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for virus information during both outbreaks as well as confidence in the government's efforts to combat Zika virus in 2016. Presidential approval also predicts beliefs about scientists’ integrity and trust in the CDC, but the directionality shifts between 2016 and 2020. Obama supporters are more likely to believe scientists are objective and trust the CDC, while Trump supporters are more apt to question the integrity of scientists and distrust science agencies. While both Obama and Trump supporters are logically more confident in these presidents’ administrations' response to the two pandemics, during COVID‐19, confidence in the government's response to the virus becomes more sharply political and relates strongly with support for President Trump. These findings suggest that the intertwining of politics and beliefs about scientists has amplified during COVID‐19 and illustrates the importance of expanded social science investigation of the science–politics nexus and its implications for ongoing pandemic‐related issues such as vaccine hesitancy and mitigating the spread of COVID‐19 variants.

THE SOCIAL ROLE OF SCIENTISTS IN SOCIETY

Science is a key social institution that shapes social life in myriad ways, and scientists’ prominent position in society in part reflects socialized views of the rigor of scientific practices (Collins and Evans 2002; Gieryn 1983; Wynne 1995). Similarly, scientists’ extensive training, technical expertise, and unique knowledge make them trusted sources of information regarding science‐related issues (Jasanoff 2010; Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Hoffman 2015; Nadelson et al. 2014). Nonetheless, as scientists become directly engaged in more contentious policy concerns and are more visible to the public, there is increasing scrutiny of their trustworthiness and credibility, and political leaders often become alternative sources for information and guidance (Bauer and Jensen 2011; Besley and Nisbet 2013; Fiske and Dupree 2014; Hamilton and Safford 2020a, 2020b; Leiserowitz et al. 2013; Motta 2018a, 2018b; Nadelson et al. 2014; Safford et al. 2014; Safford, Hamilton, and Whitmore 2017; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2020; Vraga et al. 2018; Yamamoto 2012)

Trust has many dimensions, and in the case of scientists, entails conceptions of both their professional capabilities as well as character (Fiske and Dupree 2014; Renn and Levine 1991). A recent study by Besley, Lee, and Pressgrove (2021) points to four features that are central to public perceptions of the trustworthiness of scientists—competence, benevolence, openness, and integrity. The extent to which the U.S. public perceives scientists focused on COVID‐19 as trustworthy likely links to all four of these characteristics. However, a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center highlighted Americans’ heightened concern about scientists’ integrity. They found that approximately one‐third of respondents believed that the scientific method can be used to produce any conclusion the researcher wants, and nearly half of their respondents also indicated scientists’ judgments are just as likely to be biased as other people's (Funk et al. 2019). These findings point to the importance of investigating how perceptions of scientists’ objectivity in their practices may shape pandemic‐related views.

While the practice of science is founded on rigorous methods, degrees of uncertainty are a normal part of scientific inquiry, and important components of scientific findings, such as detailed discussions of probabilities, can be confusing to laypeople (Irwin and Wynne 2003). Relatedly, misinformation and misperceptions regarding the normal process of the scientific debate have led to the erosion of scientists’ credibility (Chryssochoidis and Krystallis 2009; Iyengar and Massey 2019; Irwin and Wynne 2003; Millstone and Van Zwanenberg 2000), while dissonant science communication from both liberal and conservative political perspectives has also contributed to the deterioration of trust in the scientific community (Nisbet, Cooper, and Garrett 2015).

To instill public confidence in science, it is critical for scientists to communicate and behave in ways that demonstrate their trustworthiness as well as expertise, especially when discussing science‐based policy recommendations (Bolsen and Druckman 2015; Eichengreen, Aksoy, and Saka 2021; Fiske and Dupree 2014). Previous analyses of communication during pandemics illustrate that the media, public officials, and scientists themselves typically focus on underscoring risks and do not emphasize how supporting data were analyzed nor clearly convey limitations and uncertainty, as these purveyors of information often believe such details can be confusing or misinterpreted (Chan et al. 2018; Frewer et al. 2003; Kasperson and Kasperson 1996; Klemm, Das, and Hartmann 2016; Majid et al. 2020; Pellechia 1997). A recent cross‐national assessment of past health crises also indicates that as societies struggle to contain pandemics, trust in scientists declines over time (Eichengreen, Aksoy, and Saka 2021). These authors also discovered confusion among their respondents related to the uncertainty inherent to scientific findings, and this connected to declines in public perceptions of scientists’ trustworthiness. They suggest similar trends may be occurring in the wake of the scientific uncertainty associated with the coronavirus pandemic (Eichengreen, Aksoy, and Saka 2021). Grappling with the rising distrust in science will be critical in the future, as research shows that when scientific guidance is not clear or perceived as credible, individuals will rely on more ideologically oriented sources (Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Kreps and Kriner 2020; McCright and Dunlap 2011; Nisbet, Cooper, and Garrett 2015).

In the United States, views about science and scientists have increasingly become political (Bolsen and Druckman 2015; Brewer and Ley 2012; Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Hamilton and Safford 2020a, 2021b; Nisbet, Cooper, and Garrett 2015; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2021). This shift appears connected to a broader erosion of trust in science and links in part to growing anti‐intellectualism among some Americans. (Blank and Shaw 2015; Gauchat 2012; Merkley 2020; Motta 2018a, 2018b; Oliver and Rahn 2016). While responding to crises like COVID‐19 is of singular importance to health officials, public perceptions of pandemic responses happen within the context of other policy debates, and political polarization can affect approaches to health emergencies just as they shape other social issues (Greer and Singer 2017; Singer, Willison, and Greer 2020) The science–politics nexus has been well‐documented, and this literature underscores how the politicization of science contributes to the erosion of scientific authority, which in turn influences attitudes about scientists’ engagement in policy responses to science‐related concerns (Brewer and Ley 2012; Gauchat 2012; Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Hamilton and Safford 2020a, 2020b, 2021a; Merkley 2020; Motta 2018a, 2018b; Safford, Hamilton, and Whitmore 2017; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2020, 2021).

Wide‐ranging research has focused on what could be termed the social bases of COVID‐19 beliefs, examining issues such as perceptions of virus‐related risks, confidence in health information, compliance with social distancing and masking measures, predictors of shelter‐in‐place rates, and assessments of the government's approach to the pandemic (Adolph et al. 2021; Algara et al. 2021; Brzezinski et al. 2020; Calvillo et al. 2020; Eichengreen, Aksoy, and Saka 2021; Gonzalez et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2020; Hamilton and Safford 2021a, 2021b; Hill, Gonzalez, and Davis 2020; McFadden et al. ). Numerous studies show that science views are a key factor affecting pandemic beliefs; however, the literature also illustrates how political and ideological orientations shape perceptions of COVID‐19 and assessments of the government's response (Allcott et al. 2020; Green et al. 2020; Funk et al. 2020b; Grossman et al. 2020; Hamilton and Safford 2021a, 2021b; Kushner Gadarian, Goodman, and Pepinsky 2020; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2021). In the United States, support for former President Trump relates closely to COVID‐19 beliefs, such as perceptions of health risks and engaging in mitigating behaviors (e.g., mask‐wearing, social distancing; Graham et al. 2020; Moss et al. 2021; Shao and Hao 2020; Shepherd, MacKendrick, and Mora 2020). Given the importance of views about political leaders and science in shaping perceptions of the pandemic, further investigating how such beliefs may interconnect and establishing whether patterns during COVID‐19 are unique or parallel trends during previous pandemics are needed.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

Building on the extant literature, we hypothesize that political factors will predict perceptions of scientists, beliefs about scientists’ integrity and political leaders together will relate to pandemic‐related views, and shifts in their effects will parallel the increasing politicization of science as the COVID‐19 pandemic unfolded in 2020. Importantly, we also add a historical perspective by comparing polling data from 2020 with a survey that asked similar questions about scientists and pandemic views during the 2016 Zika virus outbreak. Considering the 2016 and 2020 data together enables us to develop a longitudinal analysis of perceptions of scientists and pandemics. As the Zika pandemic occurred during the Obama administration, it also enables us to test how support for two different U.S. presidents along with beliefs about scientists affect views of pandemics.

Our analysis draws upon three separate surveys: the New Hampshire Granite State Poll (GSP) in October 2016 (Table 1); and two waves of the Granite State Panel (GS Panel) survey in March and July 2020 (Table 2). New Hampshire's GSP is a statewide random‐sample cellular and landline telephone survey, carried out by interviewers at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) Survey Center. Several Zika‐related questions, defined in Table 1, were included in the October 2016 iteration of the GSP (response rate 20 percent—AAPOR 2016, definition 4). When COVID‐19 forced a shutdown of the UNH Survey Center's calling operations, its statewide polling transitioned to an online platform—the GS Panel. The GS Panel is a probability‐based web panel consisting of members randomly recruited from New Hampshire phone numbers. Panel members receive polls via email and earn rewards for survey completion. This study examines data from the March (n = 650) and July (n = 959) 2020 waves, which carried questions related to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table 2), including several that are nearly identical to the 2016 GSP Zika questions in Table 1. The 959 July respondents include 208 who had also responded in March. Setting the repeat respondents aside does not substantially change our results but does yield less precise estimates of change, so we have opted (with careful robustness checks) to keep the full sample here. Probability weights, applied to all graphs and analyses in this article, adjust sample results for representativeness with regard to regional population; the number of adults and telephone numbers within households; and respondent age, sex, and race.

TABLE 1.

Variable definitions with codes and weighted summary statistics for 2016 Granite State Poll (GSP; n = 577)

| Background variables |

| Gender: Male (48.9 percent, coded 0), female (51.1 percent, coded 1) |

| Age: In years (weighted mean 47.5 years, SD 17.3 years, range 18–96+) |

| Education: High school or less (19.8 percent, coded 1), some college (23.2 percent, coded 2), college (35.1 percent, coded 3), postgraduate (22 percent, coded 4) |

| Party: Democrat (1 if yes and 0 otherwise 40.3 percent), Independent (1 if yes and 0 otherwise 19.2 percent), Republican (1 if yes and otherwise 40.6 percent) |

| Obama Approve: “Generally speaking, do you approve or disapprove of the way Barack Obama is handling his job as president?” Strongly disapprove (32.1 percent, coded –3), somewhat disapprove (8.2 percent, coded –2), lean disapprove (1.5 percent, coded –1), neither/do not know (4.2 percent, coded 0), lean approve (1.6 percent, coded 1), somewhat approve (25.8 percent, coded 2), strongly approve (26.7 percent, coded 3) |

| Dependent variables |

| Scientists Adjust: “Do you agree or disagree that scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want?” Strongly disagree (24.2 percent, coded 1), disagree (19.9 percent, coded 2), neutral/do not know (12.5 percent, coded 3), agree (26.2 percent, coded 4), strongly agree (17.2 percent, coded 5) |

| Trust CDC: “As a source of information about the Zika virus, would you say that you trust, do not trust or are unsure about science agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) that study infectious diseases?” Do not (13.2 percent, coded 1), unsure (19.4 percent, coded 2), trust (67.4 percent, coded 3) |

| Federal Response: “How confident are you in the federal government's ability to respond effectively to an outbreak of Zika virus in the United States—very confident, somewhat confident, not so confident or not confident at all?” Not (14.9 percent, coded 1), not very (16.8 percent, coded 2), somewhat (55.3 percent, coded 3), very (13 percent coded 4) |

TABLE 2.

Variable definitions with codes and weighted summary statistics for 2020 Granite State Panels (GS Panels; n = 1677)

| Background variables |

| Gender: Male (50.5 percent, coded 0), female (49.5 percent, coded 1) |

| Age: In years (weighted mean 48.4 years, SD 17.2 years, range 18–91 years) |

| Education: High school or less (34.7 percent, coded 1), some college (32 percent, coded 2), college (20.9 percent, coded 3), postgraduate (12.3 percent, coded 4) |

| Party: Democrat (1 if yes and 0 otherwise, 48.1 percent), Independent (1 if yes and 0 otherwise, 10.3 percent), Republican (1 if yes and 0 otherwise, 41.7 percent) |

| Trump Approve: “Generally speaking, do you approve or disapprove of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president?” Strongly disapprove (55 percent, coded –3), somewhat disapprove (3.7 percent, coded –2), lean disapprove (1.2 percent, coded –1), neither/do not know (1.6 percent, coded 0), lean approve (2.3 percent, coded 1), somewhat approve (8.1 percent, coded 2), strongly approve (28.1 percent, coded 3) |

| Month: Survey wave, March (41.2 percent, coded 0) and July (58.8 percent, coded 1) |

| Dependent variables |

| Scientists Adjust: “Do you agree or disagree that scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want?” Strongly disagree (38.7 percent, coded 1), disagree (13.8 percent, coded 2), neutral/do not know (16.2 percent, coded 3), agree (19 percent, coded 4), strongly agree (12.4 percent, coded 5) |

| Trust CDC: “As a source of information about the Coronavirus, would you say that you trust, don't trust, or are unsure about science agencies such as the CDC that study infectious diseases?” Do not (16.2 percent, coded 0), unsure (17.7 percent, coded 1), trust (66.1 percent, coded 2) |

| Federal Response: “How confident are you in the federal government's ability to respond effectively to the current outbreak of Coronavirus in the United States?” |

| Not at all (40.5 percent, coded 1), not very (20.0 percent, coded 2), somewhat (19.8 percent, coded 3), very (19.7 percent, coded 4) |

VARIABLE DEFINITIONS AND REGRESSION MODELING

Tables 1 and 2 include descriptions of the variables used in our study along with codes for regression analysis and descriptive statistics. For demographic characteristics, we included four variables that were consistent across all three surveys: gender, age, education, and political party. Gender is dichotomized (0,1). While a small percentage of participants selected non‐binary identities, these were too few for meaningful analysis, so they are set aside here. Age is measured in years, and Education is broken into four categories, coded from 1 (high school or less) to 4 (postgraduate). Party is a three‐category variable based on self‐identification as leaning to strongly Democrat, Independent, or leaning to strongly Republican (with each party coded as 1 if yes, 0 if otherwise, to facilitate treatment of party as a categorical rather than ordinal variable). Obama Approve (2016) and Trump Approve (2020) gauged the degree to which respondents approved or disapproved of the job the two presidents were doing at the time of these surveys, coded from strongly disapprove (–3) to strongly approve (3). The approval codes are centered at zero to reduce multicollinearity and simplify the interpretation of main effects in models containing interactions. Finally, we included an indicator for survey Month among the predictors in 2020 GS Panel data, testing for changes between March (coded 0) and July (coded 1) as the COVID‐19 outbreak progressed.

Dependent variables included are Scientists Adjust, which asked participants the extent to which they agree with the statement—scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want, Trust CDC, which asks about participant trust in government agencies like the CDC as a source of information about Zika (2016 survey) and COVID‐19 (2020 surveys), and Federal Response, which queries respondents’ confidence in the federal government response to the Zika and COVID‐19 pandemics. All three dependent variables are coded as ordinal scales.

BELIEFS ABOUT SCIENTISTS, SCIENCE AGENCIES, AND GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSES DURING PANDEMICS

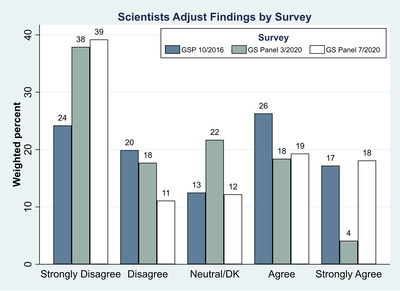

Data from the 2016 and 2020 New Hampshire polls illustrate both commonality and divergence in public perceptions of the integrity of scientists, trust in science agencies for information about viruses, and confidence in the federal response to the two pandemics. Beginning with the Scientists Adjust question, our survey data from 2016 and 2020 show notable trends in New Hampshire residents’ beliefs about the objectivity of scientists (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Weighted percent of respondents who agree or disagree that scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want, by survey

Responses to Scientists Adjust from the 2016 GSP show approximately 43 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that scientists adjust their findings to get the answer they want, 44 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed, with the remaining 13 percent of individuals stating they were unsure. Comparing these results to the March and July 2020 waves of the GS Panel, we observe a shift. In March, there was a marked decline in those strongly agreeing scientists adjust their findings from 2016 to a low of 4 percent; that number then increased back to 18 percent in July. The number of respondents agreeing stayed nearly identical across 2020 but down from 2016. The more dramatic changes were in those strongly disagreeing that scientists adjust their results, with that number increasing from 24 percent in 2016 to a high of 39 percent of respondents in the July 2020 GS Panel. These fluctuations in the number of respondents strongly agreeing between March and July 2020, and the increase in the percent strongly disagreeing, suggest public perceptions of scientists became more polarized during the course of the COVID‐19 crisis. Similarly, while 22 percent of March respondents were unsure or did not know whether they believed scientists adjusted their findings, that number dropped to 12 percent in July, implying that views about scientists became more focused in the wake of COVID‐19. While confidence in the objectivity of scientists increased overall during COVID‐19, more than a quarter of respondents still agreed with the statement that scientists adjust their findings to get the results they want. To what extent that belief predicts views about science agencies that provide information about the virus and confidence in the government's response to the pandemic is a focus for this investigation.

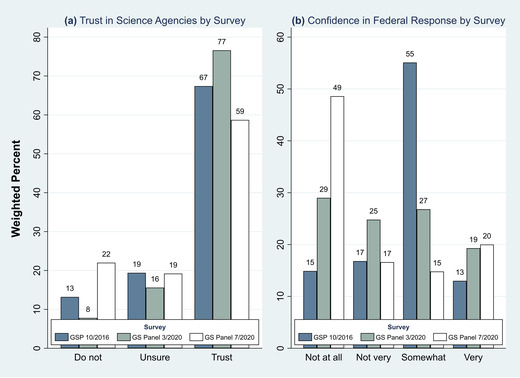

Trends in the Scientists Adjust question across the 2016 Zika and 2020 COVID‐19 pandemics provide signs of shifting societal views about scientists’ integrity. Additional survey questions show related trends in the public's trust in science agencies and confidence in the federal response to pandemics. Figure 2a shows results from the Trust CDC question from the 2016 GSP and the two 2020 GS Panel surveys.

FIGURE 2.

Weighted percent of responses to (a) whether participants trust science agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a source of information about the Zika virus (GSP 2016), or Coronavirus (Granite State Panel (GS Panel) March and July 2020), and (b) whether participants have confidence in the government's ability to respond to the Zika virus (GSP 2016), or Coronavirus (GS Panel March and July 2020), broken down by survey

During the Zika pandemic in 2016, 67 percent of GSP respondents said they trusted science agencies such as the CDC for information. At 77 percent, the corresponding percentage in March 2020 was 10 points higher at an early stage of the COVID‐19 pandemic. By July 2020, however, this percentage had fallen to 59 percent, well below even 2016 levels. Similarly, the percentage saying they did not trust science agencies for virus‐related information almost doubled in a few months, from 23 percent in March to 41 percent in July. Comparing these results with the 2016 Zika responses, we might infer that trust in the CDC was extremely high in March 2020 but then dropped noticeably in July. This pattern suggests a considerable change in public perceptions over a short period of time during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Data from the Federal Response question, which assessed confidence in the federal government's response to Zika and COVID‐19, show similar tendencies in Figure 2b. During Zika, most respondents had faith that the federal government could respond to the virus, with 68 percent being either somewhat or very confident in the government's ability to respond. Things changed in 2020 during the COVID‐19 outbreak. In March, more than half of GS Panel respondents were either not very or not at all confident in the federal response. Most notably the percent saying they were not at all confident in the response rose from 29 percent in March to 49 percent in July. Interestingly, the number who were very confident was nearly the same at 19 percent and 20 percent across the two surveys. While it is logical that views changed along with the dramatic shifts in the COVID‐19 outbreak over 2020, it is interesting to note that a consistent number of individuals remained highly confident in the federal response.

Results from Scientists Adjust, Trust CDC, and Federal Response together illustrate that while majorities of New Hampshire poll respondents did not question scientists’ objectivity, trusted the CDC, and had confidence in federal responses to Zika and COVID‐19, a significant portion did not share those views. Our findings also point to key shifts in beliefs from 2016 to 2020, more notably between the March and July 2020 GS Panels. While the tabulations in Figures 1 and 2 highlight broader patterns, they do not explain factors that might increase or decrease the likelihood respondents hold different views about scientists, science agencies, and pandemic responses. Thus, we use regression models to investigate possible predictors of beliefs about scientists and pandemics.

MODELING EFFECTS OF BELIEFS ABOUT SCIENTISTS AND PRESIDENTS ON PANDEMIC VIEWS

Probability‐weighted ordered logit regression was used to test respondent characteristics (gender, age, education) and outlook (party, presidential approval), along with month for the two 2020 surveys, as predictors of ordinal responses regarding scientists, science agencies, and government's handling of the Zika and COVID‐19 pandemics. Coefficients in ordered logit models describe the effects of a one‐unit change in an independent variable on the log odds (logit) favoring the next higher level of the dependent variable. These nonlinear effects can also be graphed in terms of probabilities.

Figures 1 and 2 showed substantial changes in all three of our dependent variables (Scientists Adjust, Trust CDC, and Federal Response) from March to July 2020. Such changes could reflect increased politicization, and more specifically the shifting messages from President Trump—whose tweets regarding the CDC, for example, turned from praise to attack during this period (Hamilton and Safford 2021b). To test the hypotheses of Trump's influence on changing perceptions, we include Trump Approve × Month interaction terms in each of our models.

Models 1 and 2 in Table 3 show the ordered logit regression of Scientists Adjust (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) on respondent characteristics, and survey month (March or July) for the 2020 data in Model 2. Analysis of the 2016 data begins to show how political factors connect to respondents’ assessments of scientists’ objectivity in their methodological practices. We find that, compared with Democrats, self‐described Independents have significantly greater odds of agreeing that scientists adjust their results to get the answers they want. More notably, we find strong Obama Approve effects, with those who approving of the way President Obama was doing his job being less likely to agree that scientists adjust their findings.

TABLE 3.

Predictors of the belief that scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want, trust in science agencies such as the CDC for virus information, and confidence in the federal government's response to pandemics. Coefficients from weighted ordered logit regressions

| Scientists Adjust | Trust CDC | Federal Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | 1. GSP 2016 | 2. GS Panel 2020 | 3. GSP 2016 | 4. GS Panel 2020 | 5. GSP 2016 | 6. GS Panel 2020 |

| Gender | 0.118 | –0.164 | –0.249 | –0.539* | 0.302 | 0.257 |

|

Age |

–0.004 |

–0.004 |

–0.008 |

0.002 |

–0.005 |

0.005 |

| Education | –0.137 | –0.362*** | 0.267* | 0.117 | 0.122 | 0.030 |

| Party | ||||||

| Democrat | (Base) | (Base) | (Base) | (Base) | (Base) | (Base) |

| Independent | 0.859** | 1.005** | –0.437 | –1.148** | –0.230 | –0.055 |

| Republican | 0.372 | 0.712* | –0.238 | –1.175 | –0.324 | 1.334*** |

| Obama Approve | –0.187** | – | 0.182** | – | 0.121*– | – |

| Trump Approve | – | 0.206** | – | 0.234 | – | 0.573*** |

| Month (July) | – | 0.891*** | – | –0.834** | – | –0.733** |

| Trump × Month (July) | – | 0.386*** | – | –0.488*** | – | 0.318*** |

| Scientists Adjust | – | – | –0.413*** | –0.676*** | –0.230** | 0.144 |

| F statistic | 10.56*** | 18.62*** | 9.14*** | 18.12*** | 5.82*** | 42.92*** |

| Survey months | Oct | Mar, Jul | Oct | Mar, Jul | Oct | Mar, Jul |

| Est. sample | 507 | 1526 | 507 | 1526 | 498 | 1515 |

***p<.001, **p <.01, * p<.05.

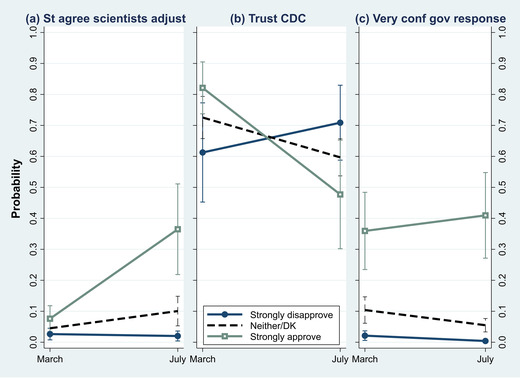

Turning to the March and July 2020 GS Panel results in Table 3, intriguing trends emerge. First, the 2020 models show negative effects from education (people with higher education have significantly lower odds of thinking that scientists adjust their findings). While we did not see education effects in the 2016 model, the 2020 results agree with other studies that found education predicts science views (Gauchat 2015; Motta 2018b; Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2020). Political effects on perceptions of scientists in 2020 are even more prominent than in 2016, with effects from both Trump approval and party. Independents and Republicans more often believe scientists adjust their results as do people who approved of President Trump. The positive main effect of Trump Approve tells us that even in March (Month = 0), Trump approvers were more likely than non‐approvers to believe that scientists adjust their findings. The main effect of Month indicates that for people with neutral views on Trump (Trump Approve = 0), the belief that scientists adjust their findings rose from March to July. But we also find a significant Trump Approve × Month interaction—so the belief that scientists adjust their findings rose more steeply among Trump approvers than other groups. Figure 3a visualizes Model 2's Trump Approve × Month interaction effect on the probability of “strongly agreeing” that scientists adjust their data. We see a widening gap between Trump‐approving and Trump‐neutral or Trump‐disapproving respondents.

FIGURE 3.

Margins plots showing Trump Approve × Month interaction effects on (a) strong agreement that Scientists Adjust, (b) Trust CDC and (c) very high confidence in Federal Response calculated from GS Panel Models 2, 4, and 6 in Table 3 (with 95 percent confidence intervals). To keep the graphs readable, lines are not drawn for intermediate levels of Trump disapproval/approval (somewhat or leaning), but they would fall between the strongly disapprove/approve lines shown

Science agencies are vital sources of information during pandemics, so assessing possible social factors that relate to trust in these organizations is critical. Models 3 and 4 in Table 3 for Trust CDC show elements of similarity and divergence between our 2016 and 2020 results, and they highlight the effects of beliefs about scientists’ integrity (Scientists Adjust) and presidential approval (Obama Approve and Trump Approve) on respondents’ views. Looking first at the 2016 GSP (Model 3), we find beliefs about scientists’ objectivity clearly influence perceptions of the trustworthiness of the CDC during the Zika pandemic: Those agreeing that scientists adjust their findings have significantly lower odds of trusting the CDC for information about the virus. Results also show that individuals with higher educational attainment were more likely to trust the CDC about Zika, pointing to the role of education in shaping assessments of the credibility of science agencies in 2016. Similar to Model 1 for Scientists Adjust, in Model 3, presidential approval again predicts attitudes toward the CDC: Those approving of President Obama tend to trust the CDC for information about the Zika virus.

Turning to the 2020 COVID‐19 surveys results in Model 4 show further links between beliefs about scientific practices and assessments of science agencies. Those agreeing that scientists adjust their findings were significantly less likely to trust the CDC for information about the new coronavirus. Political party affiliation also predicts CDC views, with Independents being less apt than Democrats to trust the CDC as an information resource. In contrast to Model 3 (2016), in Model 4 (2020), education has no effect, and women were less likely than men to trust the CDC for information about COVID‐19. The negative main effect for Month indicates that Trump‐neutral respondents were less likely to trust the CDC in July than March, but the Trump Approve × Month interaction (Figure 3b) tells us that CDC trust fell even more steeply from March to July among Trump supporters. Among those who strongly disapproved of Trump, in contrast, trust in the CDC actually rose from March to July.

Finally, understanding how views about scientists, along with other factors, affect confidence in pandemic responses is critical because successful public health interventions often rely on community‐wide support and compliance with scientific recommendations enacted by the government. Models 5 and 6 in Table 3 test predictors of the Federal Response variable during Zika and COVID‐19. As with trust in the CDC, Scientists Adjust and Obama Approve relate to confidence in the government's response to the Zika virus in 2016. Those agreeing that scientists adjust their findings were less likely to have confidence in the government's efforts to combat Zika. Conversely, Obama supporters are more likely to be confident in the federal government's approach.

Political factors are even more prominent in the 2020 findings for Federal Response (Model 6), reflecting greater polarization as the COVID‐19 crisis unfolded. Distinct from 2016, we find clearer political effects with Republicans being significantly more likely than Democrats to be confident in the government's (i.e., Trump Administration's) approach to COVID‐19, as are supporters of President Trump. In Model 6, we once again see significant changes from March to July: Trump‐neutral (Trump Approve = 0) respondents expressed lower confidence in the government's efforts in July than they had in March. However, a significant Trump Approve x Month interaction (Figure 3c) indicates that among Trump supporters, confidence in the federal government's response increased, as the pandemic was viewed through an increasingly partisan lens. The plot in Figure 3c depicts a widening gap between Trump supporters and detractors. Finally, unlike 2016, we do not find significant effects from the Scientists Adjust on confidence in the government's response. During the COVID‐19 crisis, assessments of the government's effort to combat the virus appear to narrowly reflect political factors and most importantly support or opposition to President Trump.

These regression results support our hypothesis that beliefs about scientists’ objectivity and presidential approval are interconnected and affect trust and confidence in governmental authorities attempting to address pandemics. Relatedly, our data reflect the effects of increasing politicization of COVID‐19 over 2020, and in particular, heightened distrust of scientists and science agencies among supporters of President Trump. While there are clear patterns in our results, we are circumspect about broader generalizations given our surveys are from only one U.S. state and include a relatively small subset of variables. Public trust in scientists reflects conceptions of scientists’ competence, benevolence, openness as well integrity, so measuring how the other three dimensions beyond integrity affect public perceptions of scientists would be important to support broader conclusions (Besley, Lee, and Pressgrove 2021). Similarly, variables such as religiosity, employment status, and views of corporations (that are vital sources for therapeutics and vaccines) have been found to affect pandemic views and might add to the explanatory power of the models used here, elaborating on our conclusions about identity, views about scientists, and pro‐Trump effects (Garnier et al. 2021; Gonzalez et al. 2021; Hill, Gonzalez, and Davis 2020; Latkin et al. 2021; Moore et al. 2021).

While our findings are robust, a national sample and expanded investigation of the relationships we identify using a wider range of variables and measures of science, political views, and trust would enable broader inferences. We encourage further research along these lines, as understanding shifting attitudes and beliefs about the science–politics nexus is critical not only to social scientists studying science as an institution but also to public health officials attempting to implement science‐based interventions to stem the tide of the COVID‐19 virus.

CONNECTING BELIEFS ABOUT SCIENTISTS, PRESIDENTS, AND PANDEMICS

The importance of rigorous scientific inquiry and the engagement of scientists during health pandemics cannot be understated. While data from the GS Panels in 2020 show most of the New Hampshire public think scientists are objective in their practices and science agencies are credible sources of health information, a sizable minority does not. Perceptions of scientists’ integrity is a key dimension of trust in science as an institution (Besley, Lee, and Pressgrove 2021; Dohle, Wingen, and Schreiber 2020; Fazio et al. 2021; Fiske and Dupree 2014; Kazemian, Fuller, and Algara 2021; Plohl and Musil 2021; Renn and Levine 1991). This study confirms this, and our retrospective comparison of beliefs about scientists during the Zika virus and COVID‐19 outbreaks demonstrates the longitudinal effects of science skepticism on pandemic views. These results further document how declining public trust in science impacts issues ranging from climate change to vaccine safety (Brewer and Ley 2012; Gauchat 2012, 2015; Hamilton, Hartter, and Saito 2015; Hamilton and Safford 2020a, 2020b, 2021b; Motta 2018a; Safford et al. 2014; Safford, Hamilton, and Whitmore 2017; Safford, Whitmore, and Hamilton 2020, 2021).

Political polarization has pervaded virtually every aspect of American life. While views about the practice of science and contagious diseases might seem outside the realm of politics, our findings illustrate that is not the case while also highlighting that political effects on pandemic views preceded the COVID‐19 crisis. Both in 2016 and 2020, presidential approval is a strong predictor of beliefs about scientists’ integrity, but the directionality shifts with Obama supporters being less likely to believe scientists adjust their findings and Trump supporters being more apt to believe scientist adjust their results. The fact that the agreement that scientists are not objective in their practices increased between March and July 2020 among Trump supporters also shows how this pattern amplified as the coronavirus crisis unfolded. These results, along with the party effects on Scientists Adjust in 2020, confirm related studies that point to the increasing politicization of science and COVID‐19 during the pandemic (Adolph et al. 2021; Agley and Xiao 2021; Calvillo et al. 2020: Hamilton and Safford 2021b; Shepherd, MacKendrick, and Mora 2020). Turning to trust in the CDC, the agency leading federal responses to health crises, we see similar presidential approval effects and shifts in directionality. Interestingly, however, we do not see direct effects from Trump Approve in 2020 but rather Trump Approve x Month interaction effects. As the pandemic progressed, Trump supporters increasingly distrusted the CDC for information, mirroring shifts in President Trump's own declining confidence in the CDC and conflict with the scientific community over 2020 (Frieden et al. 2020; Hamilton and Safford 2021b).

Our last dependent variable, Federal Response, provides the final evidence documenting the effects of science views and politics on pandemic beliefs. Results from 2016 parallel those for Trust CDC, with Obama supporters being more confident in the response along with individuals who believe scientists are objective in their practices. In 2020, the politicization of perspectives about the pandemic is even more marked. Beliefs about scientists’ objectivity no longer affect views, and only political variables remain significant. Our regression models show Republicans and Trump supporters are much more likely (p < 0.001) to be confident in the government's approach, and their already high confidence is amplified in July (see Figure 3). It is unsurprising that Trump supporters would be confident in his administration's approach. However, when we look at all three of our dependent variables across 2016–2020, an important trend emerges, where under President Trump, the questioning of scientists and science agencies has become polarized, and the politicization of pandemics amplified. This is an ominous trend that will undoubtedly affect ongoing efforts to stem the tide of COVID‐19 in the future.

INSTILLING CONFIDENCE IN SCIENTISTS AND SCIENCE‐BASED APPROACHES TO PANDEMICS

During the early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, Americans largely followed scientific guidance for confronting the virus and recognized the need for a collective approach for societal good. However, this solidarity waned in the summer of 2020, and the pandemic became enmeshed in the political divisiveness of the United States. Our research highlights this shift and demonstrates that not only did COVID‐19 policies become more politicized, but this process also appears to have undermined confidence in scientific authority. Scientists continue to be some of the most trusted figures in American society (Funk et al. 2020b). However, among an important subset of individuals, contentiousness surrounding the pandemic response appears to have further eroded the credibility of scientists. Into this expertise vacuum have stepped political figures, and former President Trump, in particular, offering alternative information and guidance. Some might ask to what extent is this a new phenomenon. Our study shows science and politics linked in 2016 as well, with support for President Obama affecting views of scientists and pandemic responses during the Zika outbreak. However, those political connections reflected the belief that scientists were objective in their practices, and science agencies could be trusted for information rather than political factors leading to increased questioning of scientists’ integrity and scientific authority.

What do these trends portend for the future? Scientific inquiry is crucial for understanding threats from the new coronavirus and identifying ways to combat it. While the need to “follow the science” is true, the process of instilling broader confidence in science and the belief that scientists are credible authorities is more complicated. The science–politics nexus is paramount, and for many in the deeply polarized U.S. public, political leaders like former President Trump are more trusted authorities on COVID‐19 than the scientific community. This makes fostering compliance with science‐based health recommendations and creating consensus on appropriate responses to the pandemic challenging. Nonetheless, our study points to the importance of how the public views scientists and their methodological practices in shaping pandemic‐related beliefs. This suggests that a key step toward increasing trust in science may be to pivot from a focus on scientists as technical authorities and emphasize how scientists are individuals with integrity who prioritize rigor in their practices. Such a reframing of the social status of scientists could help instill broader confidence in the scientific community as well as their guidance for combating the virus. COVID‐19 is a global threat and requires a collective approach to combat. In the future, social scientists have a vital role to play in developing further understanding of the social forces behind science and pandemic views while also highlighting factors that may facilitate the more consensual approaches needed to end the COVID‐19 crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the College of Liberal Arts, Carsey School of Public Policy, and the Research Office at the University of New Hampshire for their funding support for the three New Hampshire surveys used in this study—the 2016 Granite State Poll and the March and July 2020 Granite State Panels.

Safford, Thomas G. , Whitmore Emily H., and Hamilton Lawrence C.. 2021. “Scientists, presidents, and pandemics—comparing the science–politics nexus during the Zika virus and COVID‐19 outbreaks.” Social Science Quarterly. 102:2482–2498. 10.1111/ssqu.13084

REFERENCES

- American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) . 2016. Standard Definitions: Final Disposition of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th ed. Washington, DC: AAPOR. [Google Scholar]

- Adolph, C. , Amano K., Bang‐Jensen B., Fullman N., and Wilkerson J.. 2021. “Pandemic Politics: Timing State‐Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID‐19.” Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law 46(2):211–33. 10.1215/03616878-8802162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. M. , Fraser C., Ghani A. C., Donnelly C. A., Riley S., Ferguson N. M., G. M. Leung, T. H. Lam, and Hedley A. J.. 2004. “Epidemiology, Transmission Dynamics and Control of SARS: The 2002–2003 Epidemic.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359(1447):1091–105. 10.1098/rstb.2004.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agley, J. , and Xiao Y.. 2021. “Misinformation About COVID‐19: Evidence for Differential Latent Profiles and a Strong Association With Trust in Science.” BMC Public Health [Electronic Resource] 21(1):1–12. 10.1186/s12889-020-10103-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algara, C. , Fuller S., Hare C., and Kazemian S.. 2021. “The Interactive Effects of Scientific Knowledge and Gender on COVID‐19 Social Distancing Compliance.” Social Science Quarterly 102(1):7–16. 10.1111/ssqu.12894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H. , Boxell L., Conway J., Gentzkow M., Thaler M., and Yang D. Y.. 2020. “Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” NBER Working Paper (w26946). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3574415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M. W. , and Jensen P.. 2011. “The Mobilization of Scientists for Public Engagement.” Public Understanding of Science 20(1):3–11. 10.1177/0963662510394457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besley, J. C. , Lee N. M., and Pressgrove G.. 2021. “Reassessing the Variables Used to Measure Public Perceptions of Scientists.” Science Communication 43(1):3–32. 10.1177/2F1075547020949547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besley, J. C , and Nisbet M. C.. 2013. “How Scientists View the Public, the Media and the Political Process.” Public Understanding of Science 22(6):644–59. 10.1177/0963662511418743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank, J. M. , and Shaw D.. 2015. “Does Partisanship Shape Attitudes toward Science and Public Policy? The Case for Ideology and Religion.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 658(1):18–35. 10.1177/0002716214554756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen, T. , and Druckman J. N.. 2015. “Counteracting the Politicization of Science.” Journal of Communication 65(5):745–69. 10.1111/jcom.12171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid, M. , Brainard J., Hooper L., and Hunter P. R. 2016. “Public Health Interventions for Aedes Control in the Time of Zika Virus–A Meta‐Review on Effectiveness of Vector Control Strategies.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10(12):e0005176. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, P. R , and Ley B. L.. 2012. “Whose Science Do You Believe? Predicting Trust in Sources of Scientific Information About the Environment.” Science Communication 35:115–37. 10.1177/1075547012441691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski, A. , Kecht V., Van Dijcke D. & Wright A. L. 2020. “Belief in Science Influences Physical Distancing in Response to COVID‐19 Lockdown Policies.” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper, (2020‐56). https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/belief-in-science-influences-physical-distancing-in-response-to-covid-19-lockdown-policies/

- Butcher, P. 2021. “COVID‐19 as a Turning Point in the Fight Against Disinformation.” Nature Electronics 4(1):7–9. 10.1038/s41928-020-00532-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, G. , De Andrade M., and MacDonald L.. 2013. “Reputation, Relationships, Risk Communication, and the Role of Trust in the Prevention and Control of Communicable Disease: A Review.” Journal of Health Communication 18(12):1550–65. 10.1080/10810730.2013.840696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, D. P. , Ross B. J., Garcia R. J., Smelter T. J., and Rutchick A. M.. 2020. “Political Ideology Predicts Perceptions of the Threat of COVID‐19 (and Susceptibility to Fake News About It).” Social Psychological and Personality Science 11(8):1119–28. 10.1177/1948550620940539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. P. S. , Winneg K., Hawkins L., Farhadloo M., Jamieson K. H., and Albarracín D.. 2018. “Legacy and Social Media Respectively Influence Risk Perceptions and Protective Behaviors During Emerging Health Threats: A Multi‐Wave Analysis of Communications on Zika Virus Cases.” Social Science & Medicine 212:50–59. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chryssochoidis, G. , Strada A., and Krystallis A.. 2009. “Public Trust in Institutions and Information Sources Regarding Risk Management and Communication: Towards Integrating Extant Knowledge.” Journal of Risk Research 12(2):137–85. 10.1080/13669870802637000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, H. , Awasthi A., Agarwal Y., Gaur R. K., Dhawan G., and Chandra R.. 2020. “A Comprehensive Review on Potential Therapeutics Interventions for COVID‐19.” European Journal of Pharmacology 890:173741. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.17374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H. M. , and Evans R.. 2002. “The Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience.” Social Studies of Science 32:235–96. 10.1177/0306312702032002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dohle, S. , Wingen T., and Schreiber M.. 2020. “Acceptance and Adoption of Protective Measures During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: The Role of Trust in Politics and Trust in Science.” Social Psychological Bulletin 15(4):1–23. 10.32872/spb.4315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst, S. , Schneider C. R., Kerr J., Freeman A. L., Recchia G., Van Der Bles A. M., D. D. Spiegelhalter, and Van Der Linden S.. 2020. “Risk Perceptions of COVID‐19 Around the World.” Journal of Risk Research 23(7‐8):994–1006. 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichengreen, B. , Aksoy C. G., and Saka O.. 2021. “Revenge of the Experts: Will COVID‐19 Renew or Diminish Public Trust in Science?” Journal of Public Economics 193:104343. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, R. H. , Ruisch B. C., Moore C. A., Samayoa Granados, Boggs A. J. S. T., and Ladanyi J. T.. 2021. “Who is (not) Complying with the US Social Distancing Directive and Why? Testing a General Framework of Compliance with Virtual Measures of Social Distancing.” PLoS One 16(2):e0247520. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. T. , and Dupree C.. 2014. “Gaining Trust as Well as Respect in Communicating to Motivated Audiences About Science Topics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(Supplement 4):13593–7. 10.1073/pnas.1317505111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewer, L. , Hunt S., Brennan M., Kuznesof S., Ness M., and Ritson C.. 2003. “The Views of Scientific Experts on How the Public Conceptualize Uncertainty.” Journal of Risk Research 6(1):75–85. 10.1080/1366987032000047815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden, T. , Koplan J., Satcher D. & Besser R. 2020. “We Ran the CDC. No President Ever Politicized Its Science the WAY Trump has.” Washington Post, July 14, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/07/14/cdc-directors-trump-politics/

- Funk, C. , Hefferon M., Kennedy B., and Johnson C.. 2019. Trust and Mistrust in Americans Views of Scientific Experts. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/08/02/trust-and-mistrust-in-americans-views-of-scientific-experts.

- Funk, C. 2020a. Key Findings about Americans’ Confidence in Science and Their Views on Scientists’ Role in Society. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/12/key-findings-about-americans-confidence-in-science-and-their-views-on-scientists-role-in-society. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, C. 2020b. Polling Shows Signs of Public Trust in Institutions Amid the Pandemic. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/04/07/polling-shows-signs-of-public-trust-in-institutions-amid-pandemic.

- Garnier, R. , Benetka J. R., Kraemer J., and Bansal S.. 2021. “Socioeconomic Disparities in Social Distancing During the COVID‐19 Pandemic in the U. S.: Observational Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(1):e24591. 10.2196/24591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat, G. 2012. “Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010.” American Sociological Review 77(2):167–87. 10.1177/0003122412438225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat, G. 2015. “The Political Context of Science in the United States: Public Acceptance of Evidence‐Based Policy and Science Funding.” Social Forces 94(2):723–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24754232 [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreyesus, T. A. , and Swaminathan S.. 2020. “Scientists are Sprinting to Outpace the Novel Coronavirus.” The Lancet 395(10226):762–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30420-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn, T. F. 1983. “Boundary‐Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non‐Science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists.” American Sociological Review 48(6):781–95. 10.2307/2095325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, K. E. , James R., Bjorklund E. T., and Hill T. D.. 2021. “Conservatism and Infrequent Mask Usage: A Study of US Counties During the Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic.” Social Science Quarterly 1–15. 10.1111/ssqu.13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. , Cullen F. T., Pickett J. T., Jonson C. L., Haner M., and Sloan M. M.. 2020. “Faith in Trump, Moral Foundations, and Social Distancing Defiance During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Socius 6:2378023120956815. 10.1177/2378023120956815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. , Edgerton J., Naftel D., Shoub K., and Cranmer S. J.. 2020. “Elusive Consensus: Polarization in Elite Communication on the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Science Advances 6(28):eabc2717. 10.1126/sciadv.abc2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer, S. L. , and Singer P. M.. 2017. “The United States Confronts Ebola: Suasion, Executive Action and Fragmentation. Health Economics.” Policy and Law 12(1):81–104. 10.1017/S1744133116000244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. , Kim S., Rexer J., and Thirumurthy H.. 2020. Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors’ Recommendations for COVID‐19 Prevention in the United States. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/117/39/24144.short?rss=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, L. C. , Hartter J., and Saito K.. 2015. “Trust in Scientists on Climate Change and Vaccines.” Sage Open 5(3):21582440156. 10.1177/2158244015602752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. C. , and Safford T. G.. 2020a. Ideology Affects Trust in Science Agencies During a Pandemic. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/391. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. C. , and Safford T. G.. 2020b. Trusting Scientists More Than the Government: New Hampshire Perceptions Of The Pandemic. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/401. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. C. , and Safford T. G.. 2021a. “The Worst Is Behind Us: News Media Choice and False Optimism in the Summer of 2020.” Academia Letters. 1001. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/1001. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. C. , and Safford T. G.. 2021b.. “Elite Cues and the Rapid Decline of Trust in Science Agencies on COVID‐19.” Sociological Perspectives 1209. 10.1177/07311214211022391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T. , Gonzalez K. E., and Davis A.. 2020. “The Nastiest Question: Does Population Mobility Vary by State Political Ideology during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic?” Sociological Perspectives 0731121420979700. 10.1177/0731121420979700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A. J. 2015. How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate. Stanford: Stanford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, A. , and Wynne B.. eds. 2003.. Misunderstanding Science?: The Public Reconstruction of Science and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S. , and Massey D. S.. 2019. “Scientific Communication in a Post‐Truth Society.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116(16):7656–61. 10.1073/pnas.1805868115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. 2010. “A New Climate for Society.” Theory, Culture & Society 27(2‐3):233–53. 10.1177/0263276409361497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R. E. , and Kasperson J. X.. 1996. “The Social Amplification and Attenuation of Risk.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 545(1):95–105. 10.1177/0002716296545001010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemian, S. , Fuller S., and Algara C.. 2021. “The Role of Race and Scientific Trust on Support for COVID‐19 Social Distancing Measures in the United States.” PloS One 16(7):e0254127. 10.1371/journal.pone.0254127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, C. , Das E., and Hartmann T.. 2016. “Swine Flu and Hype: A Systematic Review of Media Dramatization of the H1N1 Influenza Pandemic.” Journal of Risk Research 19(1):1–20. 10.1080/13669877.2014.923029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, S. E. , and Kriner D. L.. 2020. “Model Uncertainty, Political Contestation, and Public Trust in Science: Evidence From the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Science Advances 6(43):eabd4563. 10.1126/sciadv.abd4563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner Gadarian, S. , Goodman S. W., and Pepinsky T. B.. 2020. Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3562796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C. A. , Dayton L., Yi G., Konstantopoulos A., and Boodram B.. 2021. “Trust in a COVID‐19 Vaccine in the US: A Social‐Ecological Perspective.” Social Science & Medicine 1982(270):113684. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiserowitz, A. A. , Maibach E. W., Roser‐Renouf C., Smith N., and Dawson E.. 2013. “Climategate, Public Opinion, and the Loss of Trust.” American Behavioral Scientist 57(6):818–37. 10.1177/0002764212458272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majid, U. , Wasim A., Bakshi S.,and, and Truong J.. 2020. “Knowledge,(Mis‐)Conceptions, Risk Perception, and Behavior Change During Pandemics: A Scoping Review of 149 Studies.” Public Understanding of Science 29(8):777–99. 10.1177/0963662520963365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCright, A. M. , and Dunlap R. E.. 2011. “Cool Dudes: The Denial of Climate Change Among Conservative White Males in the United States.” Global Environmental Change 21(4):1163–72. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, S. M. , Malik A. A., Aguolu O. G., Willebrand K. S., and Omer S. B.. 2020. “Perceptions of the Adult US Population Regarding the Novel Coronavirus Outbreak.” Plos One 15(4):e0231808. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. , Willis D. E., Shah S. K., Purvis R. S., Shields X., and McElfish P. A.. 2021. “The Risk Seems Too High”: Thoughts and Feelings about COVID‐19 Vaccination.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(16):8690. 10.3390/ijerph18168690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkley, E. 2020. “Anti‐intellectualism, Populism, and Motivated Resistance to Expert Consensus.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84(1):24–48. 10.1038/s41562-021-01112-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millstone, E , and Van Zwanenberg P.. 2000. “A Crisis of Trust: For Science, Scientists or for Institutions?” Nature Medicine 6(12):1307–8. 10.1038/82102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, S. E. , Kessler S. R., Martinko M. J., and Mackey J. D.. 2021. “The Relationship Between Follower Affect for President Trump and the Adoption of COVID‐19 Personal Protective Behaviors.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 15480518211010765. 10.1177/15480518211010765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta, M. 2018a. “The Polarizing Effect of the March for Science on Attitudes toward Scientists.” Political Science & Politics 51:782–8. 10.1017/S1049096518000938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motta, M. 2018b. “The Dynamics and Political Implications of Anti‐Intellectualism in the United States.” American Politics Research 46:465–98. 10.1177/1532673X17719507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadelson, L. , Jorcyk C., Yang D., Smith Jarratt, M Matson., S Cornell., K., and Husting V.. 2014. “I Just Don't Trust Them: The Development and Validation of an Assessment Instrument to Measure Trust in Science and Scientists.” School Science and Mathematicsx 114(2):76–86. 10.1111/ssm.12051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, E. C. , Cooper K. E., and Garrett R. K.. 2015. “The Partisan Brain: How Dissonant Science Messages Lead Conservatives and Liberals to (Dis) Trust Science.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 658(1):36–66. 10.1177/0002716214555474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J. E. , and Rahn W. M.. 2016. “Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 Election.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667(1):189–206. 10.1177/0002716216662639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pellechia, M. G. 1997. “Trends in Science Coverage: A Content Analysis of three US Newspapers.” Public Understanding of Science 6(1):49. 10.1088/0963-6625/6/1/004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plohl, N. , and Musil B.. 2021. “Modeling Compliance with COVID‐19 Prevention Guidelines: The Critical Role of Trust in Science.” Psychology, Health & Medicine 26(1):1–12. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1772988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O. , and Levine D.. 1991. “Credibility and Trust in Risk Communication.” In Communicating Risks to the Public. Technology, Risk, and Society (An International Series in Risk Analysis), edited by Kasperson R. E. and Stallen P. J. M., vol. 4, 175–217. Dordrecht: Springer. 10.1007/978-94-009-1952-5_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safford, T. G. , Hamilton L. C., and Whitmore E. H.. 2017. The Zika Virus Threat: How Concerns About Scientists May Undermine Efforts to Combat the Pandemic. Durham, NH: Carsey School. http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/299/. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, T. G. , Whitmore E. H., and Hamilton L. C.. 2020. “Questioning Scientific Practice: Linking Beliefs About Scientists, Science Agencies, and Climate Change.” Environmental Sociology 6(2):194–206. 10.1080/23251042.2019.1696008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safford, T. G. , Whitmore E. H., and Hamilton L. C.. 2021. “Follow the Scientists? How Beliefs about the Practice of Science Shaped COVID‐19 Views.” Journal of Science Communication https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/1213/. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, T. G. , and Hamilton L. C.. 2020. Views of a Fast‐Moving Pandemic: A Survey of Granite Staters’ Responses to COVID‐19. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/396/. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, T. G. , Norman K. C., Henly M., Levin P. S., and Mills K. E.. 2014. “Environmental Awareness and Public Support for Protecting and Restoring Puget Sound.” Environmental Management 53:757–68. 10.1007/s00267-014-0236-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, W. , and Hao F.. 2020. “Confidence in Political Leaders Can Slant Risk Perceptions of COVID–19 in a Highly Polarized Environment.” Social Science & Medicine 261:113235. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, H. , MacKendrick N., and Mora G. C.. 2020. “Pandemic Politics: Political Worldviews and COVID‐19 Beliefs and Practices in an Unsettled Time.” Socius 6:2378023120972575. 10.1177/2378023120972575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, M. , and Zingg A.. 2014. “The Role of Public Trust During Pandemics: Implications for Crisis Communication.” European Psychologist 19(1):23–32. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Baalen, P. J. , and van Fenema P. C.. 2009. “Instantiating Global Crisis Networks: The Case of SARS.” Decision Support Systems. 47(4):277–86. 10.1016/j.dss.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. M. , Willison C. E., and Greer S. L.. 2020. “Infectious Disease, Public Health, and Politics: United States Response to Ebola and Zika.” Journal of Public Health Policy 41(4):399–409. 10.1057/s41271-020-00243-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vraga, E. , Myers T., Kotcher J., Beall L., and Maibach E. 2018. “Scientific Risk Communication About Controversial Issues Influences Public Perceptions of Scientists' Political Orientations and Credibility.” Royal Society Open Science 5(2):170505. 10.1098/rsos.170505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, B. 1995. “Public Understanding of Science.” In Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, edited by Jasanoff S., Gerald G. E., Petersen J. C., and Pinch T., 361–88. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y. T. 2012. “Values, Objectivity and Credibility of Scientists in a Contentious Natural Resource Debate.” Public Understanding of Science 21(1):101–25. 10.1177/0963662510371435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]