To the Editor:

The increase in the cumulative incidence of COVID‐19 cases was accompanied by a gradual increase in reported pediatric cases. 1 However, the clinical course of COVID‐19 in pediatric patients with aplastic anemia (AA) has not been thoroughly investigated. As of June 2021, only one pediatric and eight adult cases of COVID‐19 in patients with AA have been reported. Some patients exhibited mild and transient symptoms, while others experienced severe manifestations with fatal outcomes. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Data on the ability of these patients to produce antibodies against the virus under insufficient immune function are also limited. We report our experience with COVID‐19 in a patient with AA receiving immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and the dynamic results of the serological assay.

A 15‐year‐old male receiving cyclosporine for AA was admitted to the University of Tokyo Hospital due to fever. He was diagnosed with very severe AA 4 months prior. Since a human leukocyte antigen‐matched sibling donor was unavailable, he received IST with corticosteroids, rabbit antithymocyte globulin, and cyclosporine combined with eltrombopag. He was discharged and barely achieved a partial response 2 months after IST initiation (Figure S1). At the time of this hospitalization, he presented with a fever and mild sore throat that was noted one day previously. His white blood cell count was 1.0 × 109/L, with absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte counts of 0.67 × 109/L and 0.18 × 109/L, respectively. The hemoglobin level was 9.8 g/dl, and the platelet count was 45 × 109/L without transfusion for more than 2 months. The serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) level was low at 503 mg/dl (reference value, 861–1747 mg/dl). Other blood examinations were unremarkable. The chest radiograph did not show any evidence of pneumonia.

On day 2 (the onset of COVID‐19 was considered day 0), the patient tested positive on nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). As a part of IST, cyclosporine was continued with trough concentrations of 150–250 ng/ml. After receiving intravenous immunoglobulin and a single dose of hydrocortisone, he became afebrile on day 2. Although the complete blood count fluctuated slightly, he did not require transfusion or granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor supplementation (Figure S2). He was discharged on day 10 and had no sequelae attributed to COVID‐19 for 5 months.

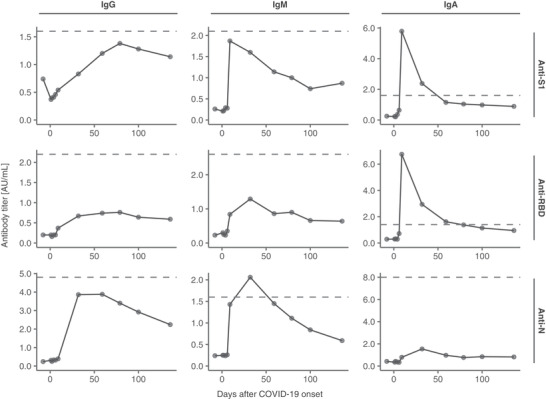

We analyzed IgG, immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) titers against three different proteins of SARS‐CoV‐2: the S1 subunit of spike protein (S1); receptor‐binding domain (RBD) within the S1 subunit, which is a major target of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralizing antibodies 7 , 8 , 9 ; and nucleocapsid protein (N) (Figure 1). The anti‐S1 and anti‐RBD IgA levels exceeded the cutoff levels on day 9 and rapidly decreased thereafter. The anti‐N IgM level was elevated on day 32. The anti‐S1 IgG and IgM and the anti‐N IgG levels also increased; however, their titers did not exceed the cutoff values. Meanwhile, the anti‐RBD IgG and IgM levels hardly changed.

FIGURE 1.

Titers of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies. We performed serial SARS‐CoV‐2 serological tests by chemiluminescent immunoassay using iFlash 3000 and iFlash‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG/IgM/IgA kits (Shenzhen YHLO Biotech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Each chart illustrates the transitions of the IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies against each of S1, RBD, and N. The dashed lines depict the cutoff values for each antibody. The cutoff values used were based on the results of 249 samples collected from the University of Tokyo Hospital (137 samples from SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA‐positive patients and 112 samples from SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA‐negative patients). IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G, IgM immunoglobulin M; N, nucleocapsid protein; RBD, receptor‐binding domain; S1, S1 subunit of spike protein; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Our patient exhibited no severe symptoms and fully recovered from COVID‐19 despite his immunosuppressed status. The clinical course of COVID‐19 was reportedly less severe in the pediatric population than in adults. 1 His young age possibly contributed to the mild clinical course. Other known risk factors for severe COVID‐19 include underlying diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and lung diseases. However, the relationship between immunocompromised states due to the underlying disease or immunosuppressive treatment and COVID‐19 severity remains controversial. Some studies reported that immunocompromised patients had more favorable outcomes than the general population. 10 , 11 Hyperactivation of immune response and excessive inflammatory reaction were associated with the pathogenesis of severe COVID‐19. 12 Among the previously reported nine cases of COVID‐19 in patients with AA, there was one patient who developed COVID‐19 during cyclosporine treatment and the patient fully recovered. 3 Therefore, immunosuppression from AA and IST, including continued cyclosporine use, possibly contributed to the uncomplicated course in our patient, despite an increased risk of viral invasion and delayed viral elimination.

The anti‐S1 and anti‐RBD IgA levels increased before the changes in the IgG and IgM levels in our patient. This observation was consistent with the findings of a previous study, which conducted a serological assay in a non‐AA cohort. 13 Since spike proteins are integral to viral entry into cells, 14 , 15 IgA might play an important role for effective control of the infection. Although an increase in anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies was observed in our patient, the levels were much lower than those in other patients with COVID‐19 in our hospital (mostly immunocompetent) (Figure S3) 16 ; particularly, the low anti‐RBD IgG level might suggest an increased risk for a future reinfection. Considering the low serum IgG level in our patient, the decrease in anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody levels could be attributed to a decreased ability to produce sufficient immunoglobulins due to AA, as reported in previous studies. 17 , 18 In a previous case series on COVID‐19 with AA, although all four patients (with one on IST) had an elevated anti‐spike protein IgG level after COVID‐19, comparable IgG levels in COVID‐19 patients without AA were not evaluated in that study. 3 The effect of IST on decreased IgG production and a favorable outcome warrants additional investigation.

In summary, we report a case of COVID‐19 in a patient with AA undergoing IST. Together with previous reports, our findings suggest that AA patients do not necessarily have a higher risk of severe COVID‐19 than the general population. Future investigations are needed to determine the optimal management for these patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study protocol was approved by the ethics board of the University of Tokyo (approval number: 2019300NI‐3), and informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of the patient.

Supporting information

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S1 Clinical course of the patient

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S2 Peripheral blood counts before and after COVID‐19

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S3 Titers of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies of the present case compared to those of other patients with COVID‐19

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the COVID‐19 team in the University of Tokyo Hospital for their dedication to patient care, and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID‐19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akcabelen YM, Koca Yozgat A, Parlakay AN, Yarali N. COVID‐19 in a child with severe aplastic anemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(8):e28443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paton C, Mathews L, Groarke EM, et al. COVID‐19 infection in patients with severe aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2021;193:902‐905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keiffer G, French Z, Wilde L, Filicko‐O'Hara J, Gergis U, Binder AF. Case Report: tocilizumab for the treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in a patient with aplastic anemia. Front Oncol. 2020;10:562625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dixon L, Varley J, Gontsarova A, et al. COVID‐19‐related acute necrotizing encephalopathy with brain stem involvement in a patient with aplastic anemia. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(5). 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y, Lu X, Chen T, Wang J. Lessons from a patient with severe aplastic anemia complicated with COVID‐19. Asian J Surg. 2021;44(1):386‐388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mazzini L, Martinuzzi D, Hyseni I, et al. Comparative analyses of SARS‐CoV‐2 binding (IgG, IgM, IgA) and neutralizing antibodies from human serum samples. J Immunol Methods. 2021;489:112937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piccoli L, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, et al. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike receptor‐binding domain by structure‐guided high‐resolution serology. Cell. 2020;183(4):1024‐1042.e1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iyer AS, Jones FK, Nodoushani A, et al. Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein in COVID‐19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(52):eabe0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minotti C, Tirelli F, Barbieri E, Giaquinto C, Donà D. How is immunosuppressive status affecting children and adults in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection? A systematic review. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e61‐e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Filocamo G, Minoia F, Carbogno S, Costi S, Romano M, Cimaz R. Absence of severe complications from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children with rheumatic diseases treated with biologic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2020;48:1343‐1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID‐19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033‐1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma H, Zeng W, He H, et al. Serum IgA, IgM, and IgG responses in COVID‐19. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(7):773‐775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, et al. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(21):11727‐11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS‐CoV‐2 by full‐length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444‐1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakano Y, Kurano M, Morita Y, et al. Time course of the sensitivity and specificity of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgM and IgG antibodies for symptomatic COVID‐19 in Japan. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sabbe LJ, Haak HL, Te Velde J, et al. Immunological investigations in aplastic anemia patients. Acta Haematol. 1984;71(3):178‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Planque MM, Brand A, Kluin‐Nelemans HC, et al. Haematopoietic and immunologic abnormalities in severe aplastic anaemia patients treated with anti‐thymocyte globulin. Br J Haematol. 1989;71(3):421‐430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S1 Clinical course of the patient

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S2 Peripheral blood counts before and after COVID‐19

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S3 Titers of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies of the present case compared to those of other patients with COVID‐19