To the editor,

Variable dermatological manifestations including acral erythema, urticaria, vasculitis, vesicular or pustular eruptions, maculopapular rash have all been reported during the course of COVID‐19. 1 Several vaccines have been developed to fight against COVID‐19, to prevent the transmission among susceptible individuals and to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with this novel viral infection. Even though proven to be quite effective, various cutaneous side effects are now being reported as the vaccination continues to be applied all over the world. Herein, we would like to report an atypical case of pityriasis rosea (PR) observed in a patient after the second dose of the mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine.

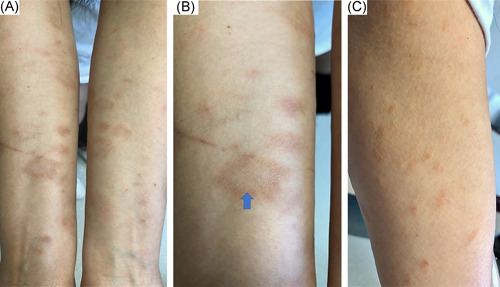

A 34‐year‐old woman with unremarkable personal history was referred to our outpatient dermatology clinic, due to the emergence of a brownish, scaly rash involving the arms and lateral aspects of the thighs. Fifteen days before the appearance of the first lesions upon the arm, she had the second dose of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. The patient did not report having any known skin disease and she denied any recent history of infection or drug administration. No accompanying systemic symptoms were present but the patient reported having mild pruritus. Dermatological examination showed multiple, tan‐colored, annular, thin plaques with central clearing and peripheral scales on the flexor aspects of both arms and lateral thighs with no involvement of the trunk (Figure 1). There was no mucosal involvement. Potassium hydroxide examination of the skin scrapings was negative. The larger annular‐scaly plaque on the right forearm was thought to represent the herald patch (Figure 1B). The patient confirmed that the larger plaque on the right forearm appeared first followed by the emergence of smaller ones, further supporting the diagnosis of PR. With clinical findings, a final diagnosis of atypical PR possibly induced by the mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine was made. She was reassured of the benign, self‐limited nature of the disease and given symptomatic treatment which resulted in the regression of the lesions.

Figure 1.

Tan colored annular scaly plaques with central clearing present upon both forearms (A), the larger, annular herald patch distinguishable on the right inner forearm (B), small, pale red to brown scaly plaques on the medial aspects of the upper arms (C)

PR is a self‐limited papulosquamous disease that tends to follow the skin cleavage lines forming a Christmas tree pattern in its classical form. 2 PR most commonly affects adolescent and young adults; human herpesvirus (HHV)‐6 and HHV‐7 reactivation, various other viral/bacterial infections, drugs, vaccinations stress, atopy, and autoimmunity are implicated in its etiopathogenesis. 2 A larger oval scaly plaque, named the herald patch, typically appears on the trunk, and a few days later smaller, erythematous, scaly eruption follows mainly involving the proximal extremities and trunk. 2 There seem to be considerable differences between vaccine‐induced PR and PR‐like eruption in terms of clinical and histopathological findings. 3 PR‐like eruption may also be seen after different kinds of drug and vaccine administration; it tends to be itchy, widespread, and confluent compared to the classical PR. 3 Moreover, mucous membranes are more likely to be affected, the herald patch is not prominent and patients commonly do not have prodromal symptoms in PR‐like eruption. 3 Blood eosinophilia may be evident and dermal eosinophils may be observed by histopathological examination in patients with PR‐like eruption. 3 Virological assays which detect HHV‐6 and HHV‐7 reactivation, confirm the diagnosis of PR. 3 In our case, the cutaneous eruption was limited only to the extremities, the herald patch was prominent on the flexor arm, there was no mucosal involvement and no blood eosinophilia was present, supporting the diagnosis of vaccine‐induced PR. However, the patient did not have any prodromal symptoms and the lesions were slightly itchy both of which are more commonly seen in vaccine‐induced PR‐like eruption. Unfortunately, we were not able to perform HHV‐6 or HHV‐7 polymerase chain reaction assay. So, we were not able to precisely distinguish between PR and PR‐like eruption for our case, but the clinical features mainly suggested the diagnosis of vaccine‐induced PR.

PR and PR‐like eruptions following both the inactivated and mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines have been reported in the literature (Table 1). In the previously reported cases, the main sites of involvement of PR and PR‐like eruption were the proximal extremities and trunk which is in concordance with the classical form of the disease. For example, Busto‐Leis et al. 11 presented two cases of vaccine‐associated PR developed 1 week and 24 h after the second dose of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine administration, respectively. These two patients had the classical herald patch and the trunk was the main site of involvement supporting the diagnosis of classical PR. 11 Inversely, our patient developed PR just upon the lateral thighs and arms after the second dose of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine; no trunk involvement was observed. Additionally, the herald patch was apparent upon the flexor aspect of the right forearm, not on the trunk as in classical PR. Therefore, with these distinctive clinical features, our patient represents an atypical form of PR. 2 Similar to our case, Temiz et al. 8 reported five cases of atypical PR such as purpuric and vesicular forms developed after COVID‐19 vaccination in a study of 31 patients. On the other hand, Adya et al. 9 observed another case of papulovesicular PR‐like eruption in a young male patient 4 days after the first dose of recombinant COVID‐19 vaccine. SARS‐CoV‐2 induced lymphopenia and functional impairment of CD4+ T cells might result in the reactivation of HHV‐6 and HHV‐7 thereby inducing PR and PR‐like eruption after COVID‐19 vaccine application. 12

Table 1.

The cases of COVID‐19 vaccine‐induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea‐like eruptions reported in the literature

| The present case | Abdullah et al. 4 | Cyrenne et al. 5 | Akdaş et al. 6 | Carballido et al. 7 | Temiz et al. 8 | Adya et al. 9 | Marcantonio‐Santa et al. 10 | Busto‐Leis 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 31 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Age (years) | 34 | 40 | 20 | 45 | 35 | Mean age: 44.9 | 21 | 22 and 54 | 26 and 29 |

| Gender | Female | Man | Female | Female | Male |

18 patients: female, 13 patients: male |

Male | Female | Male |

| COVID‐19 vaccine type | mRNA | mRNA | mRNA | Inactivated | mRNA |

14 cases: mRNA vaccine, 17 cases:inactivated vaccine |

Recombinant | mRNA | mRNA |

| Vaccine dose at the emergence of pityriasis rosea | Second dose | Second dose | First dose (but aggravated with the second dose) | First dose |

First dose (but also flared up with the second dose) |

19 cases: first dose, 12 cases: second dose |

First dose |

Case 1: second dose, Case 2: first dose (also flare with the second dose) |

Second dose |

| Associated symptoms | Pruritus | Not available | Pruritus | None | Pruritus | 24 patients: pruritus | Myalgia and febrile episode | None | None |

| Clinical type | Atypical | Typical | Typical | Typical | Typical |

26 cases: typical PR, 5 cases: atypical PR |

Atypical | Typical | Typical |

| Localization | Arms and thighs | Arms, thighs, chest, abdomen, and flanks | Trunk and proximal extremities | Trunk and proximal extremities | Trunk and proximal extremities | Not available | Trunk and proximal extremities | Trunk | Trunk |

| Time interval between the onset of pityriasis rosea and vaccine application | 2 weeks | 1 week | 2 days | 4 days | Not available | Average time: 12.7 days | 4 days |

Case 1: 7 days, Case 2: 1 week |

Case 1: 7 days, Case 2: 24 h |

All in all, we would like to report an atypical case of PR possibly induced by the second dose of mRNA‐COVID‐19 vaccine to increase awareness of the benign, temporary cutaneous side effects of COVID‐19 vaccines. PR is a self‐limited exanthem that does not require the postponement of the vaccination and can be treated symptomatically.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ecem Bostan: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Adam Jarbou: Conceptualization, Data curation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203‐211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, Parodi A. Vaccine‐induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea‐like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdullah L, Hasbani D, Kurban M, Abbas O. Pityriasis rosea after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:1150‐1151. 10.1111/ijd.15700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cyrenne BM, Al‐Mohammedi F, DeKoven JG, Alhusayen R. Pityriasis rosea‐like eruptions following vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:546. 10.1111/jdv.17342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akdaş E, İlter N, Öğüt B, Erdem Ö. Pityriasis rosea following CoronaVac COVID‐19 vaccination: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35, 10.1111/jdv.17316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carballido Vázquez AM, Morgado B. Pityriasis rosea‐like eruption after Pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185, 10.1111/bjd.20143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Temiz SA, Abdelmaksoud A, Dursun R, Durmaz K, Sadoughifar R, Hasan A. Pityriasis rosea following SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination: a case series. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Albadri W. Post Covid‐19 vaccination papulovesicular pityriasis rosea‐like eruption in a young male. Dermatol Ther. 2021:e15040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marcantonio‐Santa Cruz OY, Vidal‐Navarro A, Pesqué D, Giménez‐Arnau AM, Pujol RM, Martin‐Ezquerra G. Pityriasis rosea developing after COVID‐19 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021:jdv.17498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Busto‐Leis JM, Servera‐Negre G, Mayor‐Ibarguren A, et al. Pityriasis rosea, COVID‐19 and vaccination: new keys to understand an old acquaintance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e489‐e491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, Parodi A. Human herpesvirus‐6, ‐7, and Epstein‐Barr virus reactivation in pityriasis rosea during COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1850‐1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.