Abstract

Sociological theory and historical precedent suggest that pandemics engender scapegoating of outgroups, but fail to specify how the ethnoracial boundaries defining outgroups are drawn. Using a survey experiment that primed half of the respondents (California registered voters) with questions about COVID‐19 during April 2020, we ask how the pandemic influenced attitudes toward immigration, diversity and affect toward Asian Americans. In the aggregate, the COVID prime did not affect attitudes toward immigrants, but did reduce support for policies opening a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and reduced appreciation of California’s diversity. Respondents reported rarely feeling anger or fear toward Asian Americans, and rates were unaffected by the COVID prime. A non‐experimental comparison between attitudes toward immigrants in September 2019 and April 2020 found a positive change, driven by change among Asian‐American and Latino respondents. The results provide selective support for the proposition that pandemics engender xenophobia. At least in April 2020 in California, increased bias crimes against Asian Americans more likely reflected politicians’ authorization of scapegoating than broad‐based racial antagonism.

Keywords: COVID‐19 pandemic, discrimination, ethnoracial boundaries, immigrants, scapegoating, xenophobia

INTRODUCTION

Throughout U.S. history, dominant groups have repeatedly scapegoated immigrants during medical crises (Markel and Stern 2002). Political leaders, including former President Trump, blamed China for the pandemic and perpetrators have justified increasing numbers of hate crimes against Asian Americans by reference to the “Chinese flu.” But, we know little about the scope and depth of this reaction, and whether it targets only people of Chinese origin, all Asian Americans, only immigrants from Asia, or extends to all immigrants or even to non‐whites more broadly.

Theories in both sociology and psychology predict that exposure to novel pathogens increases in‐group members’ hostility to and avoidance of perceived outsiders. But in complex societies, intergroup boundaries— who counts as insider and who as “other”— are socially constructed. Under what circumstances, and against whom, we ask, have boundaries been constructed during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We use a survey experiment to assess the pandemic’s impact on 8800 registered California voters’ attitudes related to immigrants and immigration. California’s diversity enables us to explore the views of white, Black, Asian, and Latino citizens, all of whom are represented in substantial numbers. The survey experiment examines the effect of priming awareness of COVID‐19 on attitudes toward diversity (a boundary based on race), immigrants’ contributions to the United States (a boundary based on nativity), a pathway to citizenship for undocumented individuals (a boundary based on authorized immigration), and on negative affect toward Asian Americans (a racial boundary specific to the pandemic context).5 We also exploit the presence of an item about immigrants’ contributions on an earlier survey to examine change between September 2019 and April 2020.

We find that attitudes toward diversity and toward a pathway to citizenship were more negative among the treated group, but that attitudes toward Asian Americans and toward immigrants’ contributions were unaffected. Between September and April, attitudes toward immigrants’ contributions became more positive, due to increases in pro‐immigrant attitudes among Asian‐American respondents and among Latino respondents. Our results demonstrate that increasing the salience of disease threat can heighten some manifestations of xenophobia, but that the results vary with the way in which question framing triggers particular constructions of ethnoracial boundaries, and with ideological and ethnoracial differences among survey respondents.

XENOPHOBIA, IMMIGRATION, AND DISEASE

Scapegoating immigrants during public health crises is an American tradition. Irish immigrants were held responsible for cholera in the 1850s (Markel 1999), tuberculosis was called “the Jewish disease” in the 1890s (Kraut 2010), and Italian immigrants were blamed for the 1916 polio epidemic (Kraut 1994). In the west, Chinese immigrants were frequent targets of medical scapegoating (Shah 2001; Trauner 1978): from 1876 to 1887, San Francisco public health officials, with flimsy evidence, blamed a series of smallpox epidemics on Chinese immigrants. Later they held Chinese‐Americans culpable for outbreaks of plague, subjecting them to forced relocation (McClain 1988). Mexican immigrants were likewise scapegoated for typhus in Texas in 1916 and plague in Los Angeles in 1924. Mexican immigrants were subject to quarantine, medical inspection, and forced disinfection at border crossings through the 1930s (Molina 2006). More recently, Haitian Americans were targeted during the AIDS epidemic (Fairchild and Tynan 1994), Asian Americans were scapegoated during the 2003 SARS epidemic (Tessler et al. 2020), and U.S. Latinos faced discrimination in 2009 when the H1N1 (“swine flu”) virus was alleged to have originated on a Mexican pig farm (Huang et al. 2011).

The Covid‐19 pandemic’s racialization by former President Trump crystallized a stigmatizing association between the invasive virus and persons of Chinese descent. After January 2020, hate crimes targeting Asian Americans increased sharply (Lee and Yadav 2020; Tavernise and Oppel 2020), as did Anti‐Asian hate speech on both alt‐right and mainstream Internet sites (Schild et al. 2020). In March 2020, the FBI warned local law enforcement to prepare for an increase in anti‐Asian‐American hate crimes (Margolin 2020) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) warned that racial scapegoating represented a form of pandemic risk.

Although Asian Americans and Asian immigrants to the United States have borne the brunt of discrimination, we examine the pandemic’s effects on attitudes toward immigrants and diversity more broadly. Asians have been the most rapidly growing immigrant group in the United States for two decades and three in four adult Americans of Asian descent are first‐generation immigrants. Asians also constitute a large and growing share of the undocumented population. Thus, the category “Asian” is readily elided with the notion of diversity and with the broader category “immigrant” (Lee and Ramakrishnan 2021).

Moreover, Asian Americans are not alone in facing pandemic‐spawned discrimination. Donald Trump used the coronavirus as an excuse to restrict movement across the southern border; and as recently as March, 2021, Texas’s Republican Governor accused “illegal immigrants” of “spreading COVID” throughout his state (Bensman 2020; Bump 2021). By June 2020, about one in five Latinos reported experiencing more discrimination since the pandemic’s onset (Ruiz et al. 2020).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The hypothesis that disease produces xenophobia has roots in both sociology and psychology. In Purity and Danger (1966), Mary Douglas posited a powerful homology between the social and the biological. Fear of pollution, she argued, is universal, as is the use of ritual to protect the social body from contamination. “The body,” she wrote is a “symbol of society…a model which can stand for any bounded system. Its boundaries can represent any boundaries which are threatened or precarious” (p. 114; also Dutta and Rao 2015). Thus, when biological factors threaten order in human societies, “outsiders” (however defined) are subject to avoidance, blame, and retaliation. Consistent with this biosocial‐homology perspective, U.S. immigration opponents have often depicted immigrants as pathogens invading the body politic, an analogy that primes an association between biological agents and othered humans when disease strikes (Cisneros 2008; Ono and Sloop 2002).

Complementing Douglas’s approach, Behavioral‐immune‐system (BIS) theory in psychology views xenophobia as an evolutionary adaptation to disease. In this view, hostility to outsiders during pandemics reflects hard‐wired mechanisms that discourage intergroup contact when contagion threatens: “The behavioral component of the immune system works outside conscious awareness … to motivate avoidance of potentially infected objects and people” (Aaroe et al. 2017:278). Also complementing the sociological perspective, cognitive scarcity theory describes a generic mechanism linking disease and outgroup derogation: Environmental stressors (like disease threat) impair cognition by inhibiting higher‐order executive function, increasing the salience of primal identities, and provoking hostility to outgroups (Mani et al. 2013).

These theories all predict increased anti‐outgroup sentiment during pandemics. But they provide little guidance as to who that outgroup might be. Douglas’s theory rests on research on small‐scale, relatively isolated, tribal societies. Evidence for the psychological theories comes from controlled experiments. How might such mechanisms operate outside the lab in large, multiracial, and highly differentiated societies? In such societies, personal identities and group affiliations are diverse and fluid, depending on local traditions, elite signaling, and social interaction (Brubaker 2002; Wimmer 2013). Research thus far has yielded mixed results: Evidence of negative effects of COVID‐19 on attitudes toward immigrants in the Czech Republic, for example, but no impact on attitudes toward immigrants, Muslims, or Asians in Germany (Bartos et al. 2021; Drouhot et al 2021). We examine boundaries in the United States and ask three questions: (1) Against whom will xenophobia be directed? (2) Who will endorse xenophobic perspectives? and (3) How might different framings evoke different identities and different boundaries?

Against Whom Will Boundaries Be Drawn?

We might expect boundaries to be drawn in any of four ways. First, given the demonization of China by U.S. politicians, xenophobia might focus on Chinese‐Americans, especially Chinese immigrants. Former President Trump singled out China for specific abuse, rather than attacking Asians or Asian governments more generally. Moreover, the extraordinary diversity of the Asian‐American population in national origin (Okamoto 2003, 2014), language, socioeconomic status, conditions and recency of immigration, social views, and religion might militate toward greater specificity (Kim 2021).

We find this unlikely, however. Instead, we expect that persons with xenophobic tendencies will draw boundaries against Asian Americans as a category, rather than limiting their antagonism to people of Chinese origin. Despite the model‐minority stereotype (Lee and Zhou 2015) and despite the relatively high SES of some Asian national‐origin groups, Asian Americans have not gained the social acceptance and racial whitening (Painter 2010) experienced by European immigrant groups upon successful economic assimilation (Kim 1999; Li and Nicholson 2020; Xu and Lee 2013).6 This makes all Asian Americans vulnerable when one Asian national‐origin group is singled out for blame. That boundaries are drawn on the basis of panethnic, rather than ethnic, grounds is evident in research on hate incidents: From March 2020 to March 2021, fewer than half of Asian Americans reporting hate incidents ranging from verbal harassment to physical violence self‐identified as Chinese or Taiwanese; another 40% reported that they were of Korean, Vietnamese, Filipino, or Japanese origin (Jeung et al. 2021). Even in professional workplaces and large corporations, non‐Asian Americans find it difficult (or perhaps lack motivation) to distinguish among persons of Asian descent (Chen 2021; Lee and Ramakrishnan 2021). We anticipate that non‐Asians’ elision of national‐origin categories is reflected in attitudes as well as behavior.

Asian American are not the only panethnic population that other Americans often regard as foreign. Like Asian Americans, Americans of Hispanic origin represent a diverse set of national backgrounds and immigrant experiences, but are frequently treated as foreign by nativist citizens and politicians alike. The Trump administration directed its anti‐immigrant policies and rhetoric toward Latinos (even though immigration from Asia had exceeded Latin American immigration for years). Even earlier, rhetoric about the “vanishing European majority” (Alba 2020), fanned the flames of ethnoracial anxiety: Abascal (2015) found that exposure to stories about Latino population growth increased nationalist identification among African‐American respondents. Moreover, harsh anti‐immigrant rhetoric—what Menjivar (2021) has called a “racialization of illegality”—rendered Latinos convenient targets for scapegoating as the pandemic wore on. Precedent for contagions of disease scapegoating beyond carrier groups exists in the H1N1 epidemic, when subjects primed to think about the swine flu reported more negative attitudes toward immigrants and outgroups in general (Huang et al. 2011).

Finally, the public might have drawn an inclusive circle around fellow Americans of all backgrounds, strengthening the boundary against travelers from outside the United States. Such a response would have required strong leadership at the pandemic’s onset, similar to President Bush’s warnings against anti‐Muslim hatred after 9/11. Even had President Trump not rhetorically authorized scapegoating, the diffuse nature of the adversary and the reality of community transmission would have made it more difficult to externalize the threat. In any case, evidence that negative rhetoric poisoned attitudes toward Asian Americans confirms that boundaries were not drawn in this way (Darling‐Hammond et al. 2020).

Who Will Be Most Likely to Respond to Pandemics with Xenophobia?

A rich literature on prejudice starts from the premise that ethnoracial categories demarcate critical boundaries and group identities (Blauner 1972). Kim (1999; also Xu and Lee 2013) has proposed a triangulation theory: ethnoracial inequality, she argues, operates along two hierarchies, one demarcating socioeconomic status and one marking distance from a prototypical American. Asian Americans are close to whites near the top of the first hierarchy, but stand below whites and African Americans on the second. It follows that when this second, insider‐outsider dimension is salient, as it is when foreign pathogens strike, Asian Americans and Latinos will be vulnerable to scapegoating from both whites and African Americans.

As scapegoating victims, these outsider groups should be least likely to respond to disease priming with outgroup derogation. Under conditions of threat, members of ethnoracial categories may experience an elevated sense of shared identity and “linked fate” (Dawson 1995), producing ingroup solidarity across socioeconomic and generational lines. Consistent with this view, research on both Latinos and Asian Americans reports increased within‐group solidarity in response to hate crimes against co‐ethnics and anti‐immigrant mobilization (Huang 2021; Masuoka and Junn 2013; Zepeda‐Millán 2017). Thus, we might anticipate that increasing the salience of the pandemic would make attitudes toward co‐ethnics more positive among Asian Americans and perhaps among Latinos as well.

Politics as well as race may influence susceptibility to xenophobic primes. Voters who harbor negative attitudes toward immigrants and ethnoracial minorities, especially many conservatives and supporters of Donald Trump (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014; Perrin and Ifatunji 2020; Perry et al. 2021), may be more responsive to the COVID‐19 prime than others. Moreover, conservatives are especially likely to respond to threat by experiencing emotions associated with outgroup rejection (Inbar et al. 2009). By contrast, strong commitments to values of diversity and equality may inoculate liberals against pandemic priming effects. Consistent with this expectation, in the United Kingdom, the pandemic has strengthened anti‐immigrant views among right‐wingers, while not affecting liberals (Hartman et al. 2021).

We cannot dismiss the possibility that political liberals will be susceptible to the COVID‐19 prime, however. Negative racial schemas are available to all dominant‐group members (Bonilla‐Silva 2006), even if they are not chronically activated among racial liberals. Persons already opposed to immigration and diversity may not need priming to activate such views. By contrast, treatment effects may be strongest among persons who ordinarily hold inclusive attitudes, for whom racial stereotypes are latent but still accessible, a result found in earlier research in the Netherlands (Sniderman et al. 2004).

Finally, people who are most at risk of severe illness or economic loss should be most inclined to avoid or derogate outgroups when illness threatens. In the case of COVID‐19, this included the elderly, African Americans, Latinos, people living in COVID‐19 hot spots, workers in public‐facing jobs, and people with higher perceived COVID‐19 risk (Garcia et al. 2021).

What Frames Will Make Which Boundaries Salient?

Brubaker (2002) emphasizes the fluidity of ethnic boundaries. “Ethnicity, race, and nation,” he argues, “should be conceptualized … not in terms of substantial groups or entities but in terms of practical categories, cultural idioms, cognitive schemas, discursive frames…and contingent events” [emphasis in original]. It follows that survey questions may act as frames, evoking different boundaries, to which respondents may react differently. Thus, our four dependent variables may elicit different understandings of “us” and “them,” even within the same respondent.

One item asked about attitudes toward diversity. Research (Abascal and Ganter 2020; Bell and Hartmann 2007) has shown that respondents interpret diversity in ethnic and racial terms. By constructing a boundary in which insiders are Euro‐Americans and outsiders include everyone else, this item frames non‐whites as “diverse” yet unitary in their contrast to an imagined white majority.

A second item probed views on policies that would establish a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Using this item, Dutta and Rao (2015) found that an infectious disease prime increased opposition to a pathway. As they point out, the policy influences only the status of immigrants, not their numbers or respondents' exposure to them, so it is not logically related to health concerns. By categorizing immigrants as documented or undocumented, this item may render salient divisions (lawfully present vs. undocumented) within immigrant communities; and, given former President Trump’s emphasis on Mexican and Central American undocumented immigration, it might also activate boundaries between Asian and Latino subjects.

A third item asked about attitudes toward the impact of immigrants (in general) on life in the United States. This item produces a discursive boundary between immigrants and everyone else, on which most Americans, as descendants of immigrants, may choose either side. Finally, respondents were asked about the frequency with which they felt “anger” or “fear” (separate items) “toward Asian Americans.” This item singles out Asian Americans and divides them from other white and nonwhite ethnoracial groups, while making salient a panethnic identity that includes both Chinese Americans and other national‐origin groups.

HYPOTHESES

We anticipated that bringing the COVID‐19 pandemic front‐of‐mind with an extensive series of items about the disease would accomplish two things. First, as Mary Douglas’s theory of biological/social homology and psychologists’ BIS theory both would predict, by stimulating concerns about physical and social penetration, priming the pandemic should increase antagonism toward and fear of Asian Americans and outsiders more generally. Second, by producing stress, it should inhibit executive function and strengthen the salience of primordial group identities, thus producing less inclusive responses to items about immigration and diversity. Although we expect these effects to vary, as discussed above, among different respondents based on how they construct ethnoracial and related boundaries, and for different items based on the boundaries they elicit, we do not hypothesize a priori about such differences.

Hypothesis 1

Respondents primed with questions about COVID‐19 will express more negative views of diversity than those who are not.

Hypothesis 2

Respondents primed with questions about COVID‐19 will express less support for a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants than those who are not.

Hypothesis 3

Respondents primed with COVID‐19 items are more likely to express negative views of immigrants’ contributions to the United States than those who are not.

Hypothesis 4

Respondents primed with questions about COVID‐19 are more likely to express negative sentiments toward Asian Americans than those who are not.

We also anticipate change in response to the question about immigrants’ contributions between September 2019, before the COVID‐19 pandemic, and April 2020. Although change could result from any events transpiring over that period, the comparison is useful because its strength—the complete absence of pandemic in September—complements the survey experiment’s weakness, which is that COVID‐19 may have been chronically primed among some respondents by April 2020. Moreover, it enables us to compare long‐term change in consciously held attitudes to cross‐sectional variation triggered by implicit associations.

Hypothesis 5

Attitudes toward immigrants’ contributions to the United States will have become less positive between September 2019 and April 2020.

DATA AND METHODS

The core of the analysis is a survey experiment conducted with 8800 respondents to the April 16–April 20, 2020 poll of California registered voters by the U.C.‐ Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies. By April 16, California had 27,677 (of 663,000 national) confirmed COVID‐19 cases, and 956 Californians had died from the disease.7

The survey comprised eight batteries of questions. The key batteries used in the survey experiment appeared as the third and fourth blocks of questions. All respondents first answered basic demographic questions (age, county, and employment status/industry) and a brief set of questions about their political preferences (presidential and state) and party affiliation. The order in which the next two blocks of questions about COVID‐19 and about immigration and racial attitudes—appeared varied by respondent. Respondents were assigned randomly to one of two experimental conditions: (1) Answering the COVID‐19 battery prior to the immigration and racial‐attitudes battery or (2) Answering the immigration and racial‐attitudes battery prior to the COVID‐19 battery. There was no other difference between the two conditions and there was no introductory text to these two batteries.

The COVID‐19 module included 26 questions on personal experiences with, beliefs about, and policy preferences related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The length and depth of this battery were key to the survey experiment: participants who were randomized to respond to the COVID‐19 questions before the immigration and racial‐attitude questions engaged extensively with COVID‐19‐related themes and focused specifically on threats that COVID‐19 posed to themselves and their families. The experiment’s premise is that exposure to, and engagement with, these COVID‐19 questions situationally activated concepts related to the pandemic, above and beyond any chronic salience that may have existed by April 2020.

Invitations to participate in the survey were e‐mailed to a stratified random sample of the state’s registered voters. After data processing, poststratification weights were applied to align the sample to population characteristics of California registered voters. (For details on sample weights and sampling error, see Mitchell [2020].)

The California poll has important advantages. First, Latino and Asian, as well as Black and white, respondents are well represented. Second, almost 20% of the weighted sample consists of immigrants, reflecting the many California voters who are naturalized citizens. These characteristics make California a privileged site for transcending the black‐white paradigm in intergroup research.

At the same time, the sample is limited in three ways. First, the results are not generalizable to other parts of the United States. Given the dependence of ethnoracial boundaries on demographic distributions, power differentials, and political institutions (Wimmer 2013), we might expect different results in other regions.

Second, the sample frame consists of California registered voters, thus eliminating non‐citizens, currently incarcerated felons, and persons ruled mentally incompetent by the courts. The sample frame is highly inclusive of other Californians, including 87.9% of eligible voters, though excluding people who opt out of automatic registration through California’s motor voter law (or other means) and probably underrepresenting persons without driver’s licenses (Weber 2020).

Third, and most serious in our view, is the survey’s failure to distinguish among Asian Americans of differing ethnic backgrounds, both in the wording of items tapping attitudes toward Asian Americans and in the information available on respondents. Although we would like to have been able to compare prejudice against “Chinese Americans” to attitudes toward “Asian Americans,” we have already described abundant evidence that in‐group hostility toward particular Asian national‐origin groups is almost always generalized to Asian Americans as a whole (Chen 2021; Jeung et al. 2021). The inability to distinguish among the views of Asian Americans from different national backgrounds is a more serious problem.

Outcome Variables

Outcome variables assess attitudes toward diversity, immigration, a pathway to citizenship, and Asian Americans. All were recoded if necessary so that higher values represented more xenophobic attitudes. Unless noted, all questions refer to the April 2020 survey.8

Diversity

Respondents were asked: “Is California’s diversity an advantage or disadvantage?” (a 3‐point scale recoded as 1 = “More of an advantage,” 2 = “Both an advantage and a challenge,” and 3 = “More of a challenge and source of problems”).

Pathway to Citizenship

Respondents were asked whether: “There should be a formal pathway to citizenship for immigrants who arrived in the United States illegally” (a 5‐point scale from 1 = “Agree strongly to 5 = “Disagree strongly”).

Immigrants’ Contributions

In April 2020 respondents were asked: “Do immigrants make the United States a worse or better place to live?” (a binary variable, recoded as 0 = “Better place to live,” 1 = “Worse place to live”). In September 2019, respondents were asked: “In your opinion, do immigrants make the United States a better or worse place to live,” with the same coding.

Negative Affect toward Asian Americans

Respondents were asked: “How often have you felt Anger/Fear [separate items] toward Asian Americans?” (3 response options: “1 = Rarely,” “2 = Sometimes,” or “3 = Often”).

Independent Variables

Experimental Condition

The main independent variable was the respondent’s condition in the survey experiment: a dummy variable equal to 1 if questions about COVID‐19 (the pandemic‐ threat condition) preceded questions about immigration, diversity, and intergroup affect, and equal to 0 otherwise.

September 2019 vs. April 2020

A dummy variable in analyses pooling respondents to the immigrants’ contribution item in both months (April = 1, September = 0).

Ethnoracial Identity

Respondents reported their racial identifications, which were converted into five binary variables (Latino, Black, Asian, Native American/Alaskan Native/Other, with white as the reference category).

Political Ideology

Respondents reported their political views on a 5‐point scale (recoded 1 = Very liberal, 2 = Somewhat liberal, 3 = Moderate, 4 = Somewhat conservative, 5 = Very conservative).

Trump Approval

Respondents were asked whether they “approve or disapprove of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president” using a 5‐point scale (recoded to 1 = Disapprove strongly, 2 = Disapprove somewhat, 3 = Neither approve nor disapprove, 4 = Approve somewhat, 5 = Approve strongly).

COVID‐19 Threat Measures

Several questions assessed respondents’ relative risk of contracting COVID‐19 and their perception of the threat that contracting COVID‐19 would pose to them or their families. We used these variables to construct scales, respectively, of perceived economic threat and perceived health threat. The perceived health‐threat scale comprises six equally weighted items that loaded together in a principal‐axis factor analysis. The items include a binary indicator for whether COVID‐19 is a major threat to “your personal/ family health”; four measures of the extent to which the following are problems (where responses of “very serious problem” and “somewhat serious problem” were recoded to “1” and responses of “not much of a problem,” “not a problem” or “unsure” were recoded “0”): “getting sick from the coronavirus/getting COVID‐19,” “not being able to get medical care,” “not being able to get tested for COVID‐19,” and being “unable to get cleaning supplies or hand sanitizer”; and, finally, a 4‐point scale of concern about getting coronavirus and requiring hospitalization (recoded so that “very concerned” = 1 and “not too concerned” and intermediate responses = 0). The index ranged from 0 to 6. A measure of perceived economic threat used seven response items that loaded on one factor, including two binary indicators for whether COVID‐19 was a major threat to “your employment” and “your personal/family financial situation”; and five recoded binary measures of how much the respondent worried about: “not being able to pay for basic necessities (e.g., food, medication, rent, mortgage),” “losing my job,” “lacking paid sick leave,” “reduced wages or work hours,” and “unable to work remotely or working under dangerous conditions (i.e., close proximity to others).” Responses indicating the highest threat level were summed to create the index (range 0–7). Geographic threat is quantified as county‐level COVID‐19 deaths per 1000 residents as of April 18, 2020.9

Individual Controls

All models include controls for education, age, gender, U.S. nativity, Evangelical Christian self‐identification, and logged income. Education is coded with dummy variables indicating (a) B.A. degree or higher and (b) some college, with (c) high school or less omitted. Age is in years in the main models, but a dummy for age over 60 is used in models examining interactions of treatment with vulnerability. Gender is coded 1 = male, 0 = female. (“Other” gender is in the model but not reported due to very small numbers.) Income was self‐reported on a 9‐point scale ranging from <$20,000 to >$200,000, with logged median range values.10 U.S. nativity and Evangelical Christian identification are binary. Descriptive statistics and correlations for 2020 appear in Table I. Descriptive statistics for 2019 appear in Appendix A.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | Diversity 1 | Immigrants 2 | Path 3 | Toward Asian Americans: Anger | Toward Asian Americans: Fear | Covid prime 4 | Latino/a | Black | Asian | White | Male | Fem‐ale | Trump approval | Cons‐ervat‐ism | Age | High school or less | Some college | B.A. or more | U.S.‐Born | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity | 1.64 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 3.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Immigrants | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.43 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Pathway | 2.12 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.34 | 0.29 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Toward Asian Americans: Anger | 1.29 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |||||||||||||||||

| Toward Asian Americans: Fear | 1.15 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.57 | ||||||||||||||||

| Covid prime | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||||||||||

| Latino/a | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.01 | −‐0.02 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Black | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.13 | |||||||||||||

| Asian | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.20 | −0.09 | ||||||||||||

| White | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.59 | −0.27 | −0.43 | |||||||||||

| Male | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||||||||

| Female | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.00 | −0.05 | −0.97 | |||||||||

| Trump approval | 2.31 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.12 | ||||||||

| Conservatism | 2.74 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.67 | |||||||

| Age | 47.92 | 18.45 | 18.00 | 102.00 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.16 | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.22 | −0.05 | −0.14 | 0.30 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.20 | ||||||

| High school or less | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.14 | ‐0.10 | |||||

| Some college | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.39 | ||||

| B.A. or more | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.19 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.16 | −0.17 | 0.09 | −−.55 | −0.55 | |||

| U.S.‐Born | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.25 | 0.05 | −0.27 | 0.38 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.00 | ||

| Income | 106738 | 99468 | 10000 | 347006 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.21 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.09 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.23 | −0.13 | 0.32 | 0.02 | |

| Evangelical | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.07 |

California poll, April 2020.

“Is California’s diversity an advantage or disadvantage?”

“Do immigrants make the United States a worse or better place to live?”

“There should be a formal pathway to citizenship for immigrants who arrived in the United States illegally.”

Covid battery asked first =.

Analytic Strategy

To assess the effect of experimental condition on diversity beliefs, support for a pathway to citizenship, and anger toward or fear of Asian Americans, we use ordered logistic regression (Fullerton 2009) with a dummy variable for condition (treated vs. untreated). To assess the effect of experimental condition on beliefs about immigrants’ contributions to the United States (a binary variable), we use a logistic regression with a binary indicator for treatment condition or, for the combined sample, for survey month (September or April). In each model, we include terms for ethnoracial identity, Trump approval, political ideology (liberal/conservative), and controls.11 In order to examine variation in response to the pandemic prime, for all of the dependent variables we examine interactions between treatment condition and three sets of moderators: measures of ethnoracial identity, political beliefs, and real or perceived vulnerability to the pandemic.12

We use the full sample of registered California voters for the analyses. (Replications with only the approximately 80% of respondents who were native‐born yielded substantively identical results.) Because attitude measures were recoded when necessary to place conservative or xenophobic views at the high end of their scales, positive coefficients always indicate shifts toward more anti‐immigrant or antidiversity positions. Respondents were assigned randomly to the COVID‐19 prime treatment group, but we report treatment effects from models including full controls, both against the possibility that the groups are imbalanced and to examine other factors that influence these attitudes.

RESULTS

Did Priming Disease Awareness Increase Xenophobic Responses?

We hypothesized that respondents randomly chosen to answer questions about COVID‐19 before responding to questions about immigration, diversity, a pathway to citizenship, and Asian Americans would express more negative attitudes toward all four than respondents who had not yet been exposed to the COVID‐19 items. Priming disease awareness, we reasoned, would stimulate xenophobic reactions consistent with Douglas’s biosocial‐homology theory, and with complementary psychological theories. Results appear in Table II.

Table II.

Ordinal Logit and Logistic Regressions of Diversity and Immigration Attitudes and Anti‐Asian Sentiment on Experimental Condition and Independent and Control Variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is California’s diversity an advantage or disadvantage? | Experiment ‐ Do immigrants make the United States. a worse place to live? | There should be a formal pathway to citizenship for immigrants who arrived in the United States illegally | Anger toward Asian Americans | Fear toward Asian Americans | Sep/Apr —Do immigrants make the United States a worse place to live? | |||||||

| Covid prime | 0.351*** | (0.060) | −0.051 | (0.118) | 0.128* | (0.056) | 0.020 | (0.066) | 0.038 | (0.089) | ||

| April 2020 | −0.421*** | (0.102) | ||||||||||

| Male | −0.177** | (0.061) | −0.057 | (0.121) | 0.179** | (0.057) | 0.224** | (0.069) | 0.175 | (0.093) | 0.179 | (0.096) |

| Latino/a/Hispanic | −0.146 | (0.089) | −0.764*** | (0.190) | −0.303*** | (0.082) | 0.068 | (0.100) | −0.130 | (0.141) | −0.313* | (0.138) |

| Black/African American | 0.155 | (0.185) | 0.740* | (0.339) | −0.199 | (0.164) | 0.372* | (0.171) | 0.126 | (0.253) | 0.796** | (0.277) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.098 | (0.109) | −0.532* | (0.245) | 0.281** | (0.096) | 0.884*** | (0.105) | 0.657*** | (0.150) | −0.309 | (0.180) |

| Trump approval | 0.371*** | (0.028) | 0.727*** | (0.055) | 0.328*** | (0.027) | 0.018 | (0.032) | 0.009 | (0.045) | 0.820*** | (0.032) |

| Conservatism | 0.545*** | (0.039) | 0.419*** | (0.077) | 0.460*** | (0.038) | 0.163*** | (0.044) | 0.223*** | (0.064) | ||

| US‐Born | 0.339*** | (0.090) | 0.197 | (0.170) | 0.005 | (0.076) | −0.170 | (0.088) | −0.269* | (0.127) | 0.316* | (0.135) |

| Age | 0.006*** | (0.002) | 0.014*** | (0.003) | 0.006*** | (0.002) | −0.001 | (0.002) | −0.001 | (0.003) | 0.011*** | (0.003) |

| Some college | −0.115 | (0.091) | 0.053 | (0.156) | 0.307*** | (0.091) | −0.006 | (0.101) | 0.023 | (0.134) | −0.132 | (0.124) |

| B.A. or more | −0.452*** | (0.088) | −0.444** | (0.151) | 0.253** | (0.084) | 0.007 | (0.095) | −0.036 | (0.126) | −0.453*** | (0.122) |

| Logged income | −0.034 | (0.034) | −0.239*** | (0.064) | 0.066* | (0.031) | −0.076* | (0.037) | −0.122* | (0.048) | −0.189*** | (0.050) |

| Evangelical | −0.286** | (0.090) | −0.392** | (0.139) | −0.306*** | (0.088) | −0.000 | (0.097) | −0.035 | (0.126) | −0.147 | (0.110) |

| Constant | −3.491*** | (0.750) | −2.694*** | (0.589) | ||||||||

| cut1 | 2.202*** | (0.394) | 3.038*** | (0.366) | 0.801 | (0.430) | 1.084 | (0.571) | ||||

| cut2 | 4.841*** | (0.398) | 4.332*** | (0.367) | 3.485*** | (0.444) | 3.416*** | (0.594) | ||||

| cut3 | 4.986*** | (0.367) | ||||||||||

| cut4 | 5.846*** | (0.371) | ||||||||||

| N | 8,472 | 8,277 | 8,487 | 8,339 | 8,342 | 12509 | ||||||

California poll, September 2019 and April 2020. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. Reference categories are Covid prime = 0, April 2020 = 0, female, white, nonnative and less than high school education. “Other gender” and “Other race” included in models but omitted from table due to small Ns.

Diversity

Respondents held mixed views: 48% saw diversity as an advantage; 40% saw diversity as both an advantage and disadvantage; and 12% viewed it as a problem or challenge. Consistent with expectations ( Hypothesis 1 ), respondents exposed to COVID‐19 items evaluated diversity significantly more negatively than other respondents, both with and without controls. In addition to the treatment effect, approval for President Trump, conservative self‐identification, U.S. nativity, and age were associated with negative views of diversity, net of other effects. By contrast, being male, having earned a BA, logged income, and Evangelical faith were significantly associated with more positive evaluations.13

Pathway to Citizenship

Views of whether the federal government should provide a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants were largely positive, with 72% favoring such a pathway “somewhat” or “strongly,” 19% opposing it, and 9% uncertain. Consistent with Hypothesis 2 , respondents exposed to the COVID‐19 prime were significantly less sympathetic to creating a pathway. Trump support, conservatism, being male, age, higher education, logged income, and Asian‐American identity (especially for naturalized citizens) were significantly associated with opposition.14 By contrast, Evangelical faith and Latino identity were both associated with support for this policy.

Immigrant Contributions

We find no COVID‐19 treatment effect on beliefs about immigrants’ contributions to the United States, disconfirming Hypothesis 3. All but the most conservative California voters share a consensus on immigrants’ value. More than 88% agree that immigrants make the United States a better place to live, including almost all “somewhat” or “very liberal” respondents and even a small majority of “very conservative” voters. Logged income, college graduation, and Evangelical self‐identification are associated with more positive evaluations. Latinos’ and Asian American’ attitudes were significantly more positive, and African Americans’ attitudes significantly more negative, than those of whites. Trump approval, conservatism, and age were also associated with more negative views.

Negative Affect Toward Asian Americans

We expected the COVID‐19 prime to increase reported anger and fear toward Asian Americans due to politicians’ association of China with COVID‐19, as well as the rise in hate crimes against Americans of Asian descent. Most Californians appeared unaffected, however: large majorities indicated that they “rarely” felt either anger (72%) or fear (85%) toward Asian Americans, and fewer than 3% reported that they “often” felt either emotion. There was no treatment effect on these responses, disconfirming Hypothesis 4. Men and African Americans reported experiencing more anger toward Asian Americans than did women or whites, and U.S.‐born respondents reported more fear than the foreign‐born. Asian Americans reported experiencing both emotions more, perhaps due to more frequent interaction with co‐ethnic peers and kin.

Pre‐ and Post‐Pandemic Attitudes about Immigrant Contributions

The COVID‐19 survey prime examines the effect of activating an implicit association between the pandemic and attitudes toward immigrants and ethnoracial others. It does not assess diachronic effects on attitudes of living with the pandemic. Fortunately, the September 2019 California Poll contained an almost identical item about whether immigrants make the United States. a “better or worse” place to live, permitting examination of attitude change from before the pandemic to March 2020, when California began to feel its effects.

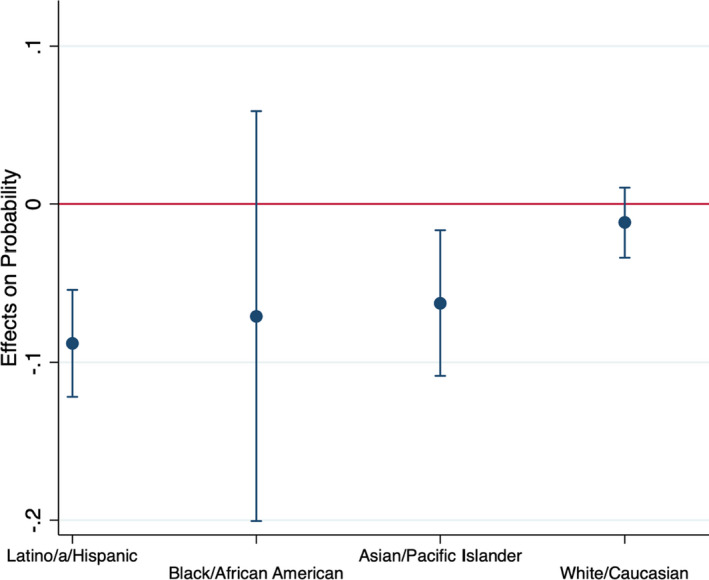

Contrary to Hypothesis 5, attitudes toward immigrants’ contributions were significantly more positive in 2020 than in 2019. The positive shift from September to April is mainly attributable to an increase in favorable attitudes of Latinos and Asian Americans, two groups with substantial recent immigration. This result is consistent with the shared‐fate conception of ethnic identity (Dawson 1995; Huang 2021), with Latino and Asian‐American citizens circling their respective wagons around the value of immigration in the face of attacks by politicians and social media activists (Fig. 1). Political conservatism, age, and U.S. nativity were all associated with more negative evaluations of immigrants’ contributions. Besides being Latino or Asian, income, having graduated from college, and Evangelical self‐identification were associated with significantly more positive views.

Fig. 1.

Effect of April Survey compared to September Survey on the predicted probabilities of responses to Immigrants’ Contribution item* by ethnoracial identity.

California poll, September 2019 and April 2020. N = 12,509. * “Do immigrants make the U.S. a worse or better place to live?” High scores represent more anti‐immigrant responses.

Who Responded Most to the COVID‐19 Prime?

We turn now to analyses of statistical interactions between the COVID‐19 prime and, respectively, ethnoracial identity, political attitudes, and pandemic vulnerability. Because we use ordinal logistic regression, the conventional practice of reporting multiplicative interaction‐term coefficients would yield misleading results (Mize 2019). Instead, we first examine each interaction’s joint average marginal effect on the dependent variables. Where the joint effect is statistically significant, we examine marginal treatment effects on the probability of each level of the outcome variable level for each category of the interacting variable, assessing significance with second‐difference Wald tests (Mize 2019). Significant interactions are presented with graphs illustrating priming effects over the distribution of the moderating variable.

Interactions With Ethnoracial Identity

Racial triangulation theory suggests that “insider groups”— European Americans and to a lesser extent African Americans—will be more prone to respond to pandemic threat with distancing and hostility than Latinos or Asian Americans. Because of the historical othering of Asian Americans, and the relative recency of immigration of both many Asian‐American and Latino ancestry groups, these groups are more distant from the prototypical American and thus less likely to respond defensively to symbolic penetration. From this perspective, then, whites and African Americans should be more susceptible to priming effects than Asian Americans and Latinos.

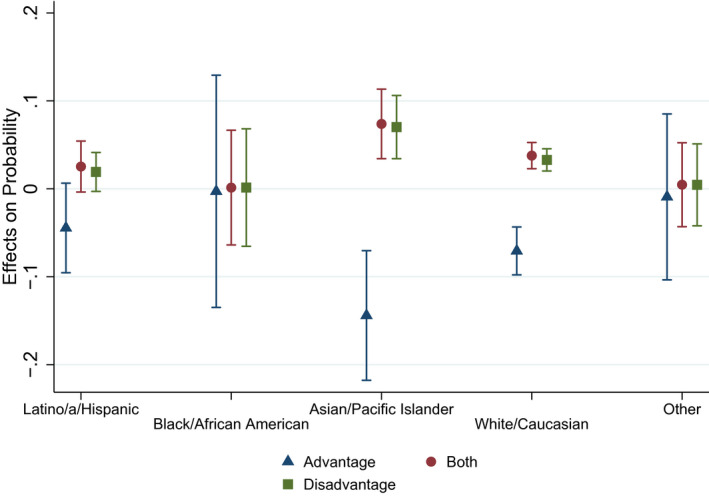

Consistent with this view, whites exposed to the COVID‐19 items first were significantly more likely to express less positive views of diversity, with more of them selecting the “more of a challenge” option and fewer choosing the most positive response. Contradicting this perspective, however, Asian Americans were, as well (Fig. 2). Exposure to treatment did not affect African‐American or Latino respondents. Wald tests comparing the effects of treatment on paired ethnoracial groups found significant differences between effects on Asians versus those on Latinos and, marginally, on African Americans, but not between whites and other groups.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Covid prime on the predicted probabilities of responses to Diversity* by race.

California poll, April 2020. N = 8,472. *“Is California’s diversity an advantage or disadvantage?”

The treatment effect for the 2020 item asking whether immigrants make the United States better or worse was significant only for Asian Americans, for whom treatment significantly increased the (very low) probability of expressing negative views of immigrants (Fig. 3). The strength of this effect differed significantly from the (nonsignificant) treatment effect for whites.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Covid prime on the predicted probabilities of responses to Immigrants’ contributions, by ethnoracial identity*.

California poll, April 2020. N = 8,277. * “Do immigrants make the United States a worse or better place to live?” High scores represent more anti‐immigrant responses.

Results were similar for the pathway‐to‐citizenship policy question, with significant treatment effects on Asian Americans, who were less likely to support and more likely to oppose a pathway if exposed to the COVID‐19 items, but no treatment effects for Latino, African Americans, or whites (Fig. 4). Again, the pairwise difference in the slope of treatment effects between Asian Americans and whites was statistically significant.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Covid prime on the predicted probabilities of responses to Path* by ethnoracial identity.

California poll, April 2020. N = 8,487. * “There should be a formal pathway to citizenship for immigrants who arrived in the United States illegally.”

There were no differences by ethnoracial identity in the (nonsignificant) effects of answering the COVID‐19 items first on anger toward or fear of Asian Americans.

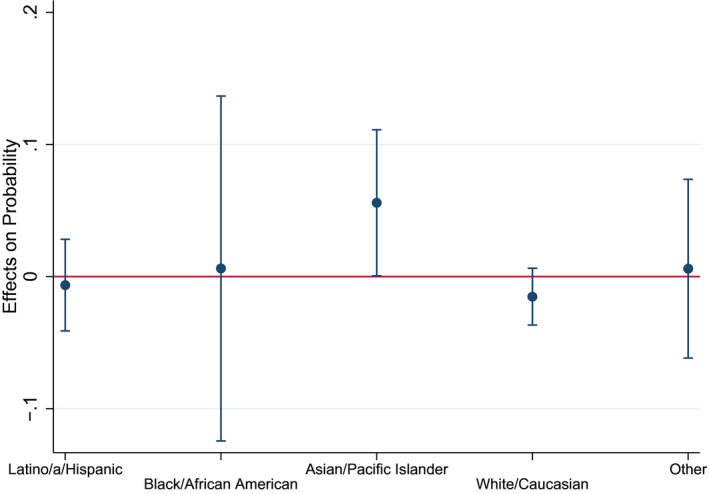

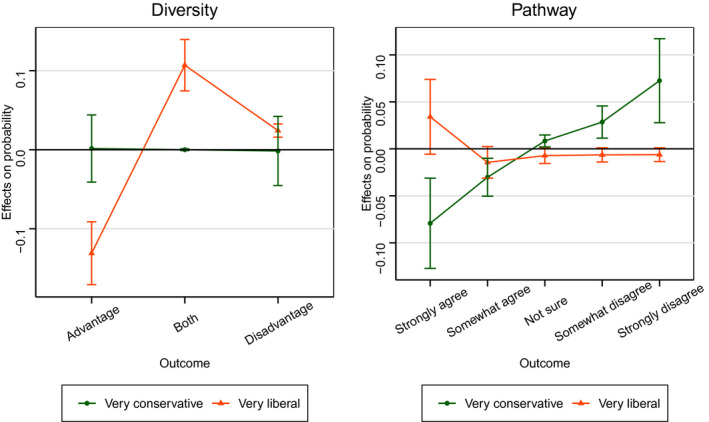

Effects of Liberalism/Conservatism on Responsiveness to Treatment

We expected the COVID‐19 prime to interact with existing beliefs about ethnoracial boundaries, so that treatment would affect conservatives, who express more negative views of immigration and diversity, more than liberals. We acknowledged the possibility, however, that priming might more strongly affect liberals, for whom negative stereotypes are acquired but less chronically activated.

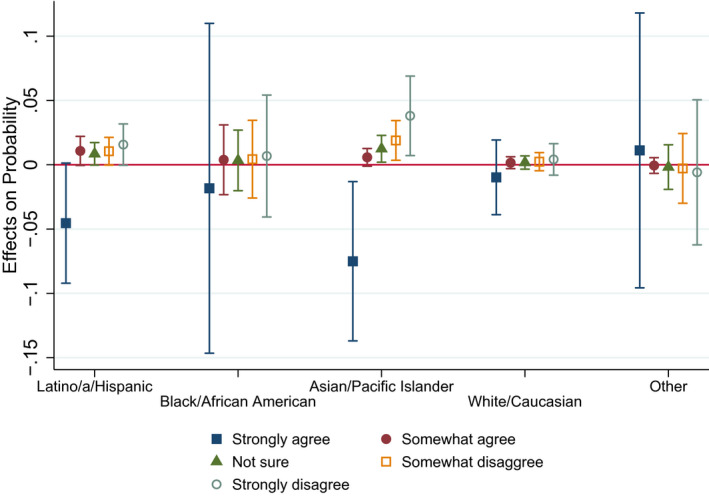

Results for the diversity item (Fig. 5, left panel) provide support for the second view: the COVID‐19 treatment significantly increased the probability of expressing less positive views of diversity, but the effect’s strength declined as political conservatism increased. Treatment drove few liberals to embrace the most critical view of diversity, instead shifting them from very positive to mixed. Very liberal respondents in the treatment condition were 10% less likely to indicate that diversity is advantageous, and 10% more likely to describe diversity as both an advantage and disadvantage, than their unprimed counterparts. Primed conservative respondents were unaffected. Even in the treated group, however, conservatives remained far more negative.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Covid prime on the predicted probabilities of responses to Diversity* and Pathway* by conservatism.

California poll, April 2020. N = 8,472. *“Is California’s diversity an advantage or disadvantage?” * “There should be a formal pathway to citizenship for immigrants who arrived in the United States illegally.”

By contrast, responses to the question about a pathway to citizenship were consistent with the expectation that conservatives would be more strongly affected by being made to focus on disease (Fig. 5, right panel). The more politically conservative the respondent, the more treatment reduced the probability of support and increased the probability of opposition.

There were no significant interactions between political beliefs and treatment condition on attitudes about immigrant contributions. Nor were there such interactions for the insignificant effects of the COVID‐19 primes on anger toward or fear of Asian Americans.

Impact of COVID‐19 Threat on the Strength of the Treatment Effect

Both biosocial‐homology theory and BIS theory suggest that COVID‐19 priming effects would be greater for respondents who experienced more real or perceived pandemic threat: Black or Latino respondents, persons over 60, respondents in counties with high death and infection rates, or those reporting high perceived health or economic threat. None of these expectations received support.

Study Limitations

Before we discuss these results, several limitations must be reiterated. First, the sample includes only registered voters. If the 12% of eligible voters who remain unregistered are more politically alienated, ideologically extreme, or mentally unstable than registered voters, we may underestimate the impact of the pandemic on negative attitudes toward immigrants or Asian Americans. Second, our sample is limited to California residents, a uniquely ethnoracially diverse population, with high rates of immigration and many naturalized citizens among its voters. Because intergroup relations are shaped by particular histories and intergroup ecologies (Wimmer 2013), results might differ in other parts of the United States. Third, we lack information on Latino and Asian‐American respondents’ national origins. Each of these pan‐ethnicities include people from many nations, with significant internal variation in social and political perspectives (Okamoto and Mora 2014). Fourth, media coverage of the coronavirus and life changes that accompanied the pandemic may have chronically activated awareness of pandemic threat among some respondents by mid‐April. Insofar as this occurred, we may underestimate the influence of the pandemic on attitudes. Finally, politicians’ changing rhetoric makes the objects of disease scapegoating a moving target. References to the “Chinese flu” or the “Kung flu” in summer 2020 may have exacerbated negative effects on attitudes toward Asian Americans. High incidence of COVID‐19 in meat‐packing plants with predominantly Latino immigrant workforces may have increased stigmatization of Latinos more generally.

DISCUSSION

First, what lessons can readers concerned with the impact of the pandemic on attitudes toward immigrants and Asian Americans draw from our findings? Second, what do the analyses contribute to the evaluation of the theoretical frameworks that structure our hypotheses?

Implications for Effects of Pandemic on Xenophobia

This research originated in concern based on press accounts, theory, and historical precedent, that the COVID‐19 pandemic was poisoning some Americans’ feelings toward immigrants, immigration, and, especially, Asian Americans The survey experiment provides mixed evidence that this had occurred among California voters. Priming awareness of pandemic threat with a battery of items about COVID‐19 reduced enthusiasm for California’s diversity and support for creating a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Still, most California registered voters continued to believe that immigrants make the United States a better place, Latinos and Asian Americans even more so than before the pandemic. These results suggest that the pandemic may have exacerbated discomfort with policies aimed at assisting outsider groups perceived as breaking the rules (i.e., undocumented persons), without altering respondents’ self‐understanding of the United States as a nation of immigrants.

Additionally, despite the well‐documented increase in anti‐Asian hate incidents, we find no evidence that increasing the pandemic’s salience in the context of a survey yielded greater anti‐Asian affect. Exposure to the COVID‐19 questions had no effect on self‐reports of anger against or fear of Asian Americans. Moreover, the proportion of respondents who said that they “often” felt either emotion was vanishingly low.

The increase in hate crimes and hate speech is troubling and undeniable, however. Such trends may result either from an increase in the number of prejudiced people; or from an increase in the probability that prejudiced people will act upon their prejudices. These results raise the possibility that the mechanism behind the rise in anti‐Asian hate was the latter, stemming from perceptions of already prejudiced persons that elite expressions of bias made such actions acceptable, rather than reflecting a broad increase in antagonism toward Asian Americans (Flores 2017).

Implications for Theory

The main‐effect hypotheses are based on Mary Douglas’s (1969) theory of biosocial homology, which holds that a symbolic homorphism between physical bodies and social collectivities produces a tendency for communities to strengthen boundaries against perceived outsiders in the face of biological threat. Activating awareness of disease threat with a battery of items about COVID‐19 produced significantly more negative views of diversity and less support for policies offering a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants among respondents who received this treatment. Because Americans interpret questions about diversity as referring to ethnoracial difference (Abascal and Ganter 2020), the diversity item evokes categorical boundaries between members of any one ethnoracial category and all others. In the face of pandemic threat, persons in all groups may view persons outside their own category as threats rather than resources. The “pathways” item evokes a different kind of boundary: between documented and “illegal” immigrants, permitting respondents to support “good” immigration, while rejecting “bad,” which they may associate with disorder and disease.

That the COVID‐19 prime did not elicit more negative assessments of immigrants’ contributions and failed to increase expressions of anger or fear toward Asian Americans points to the moderating effect of group boundaries on the relationship between xenophobic attitudes and pandemic threat. The item that asks respondents to evaluate immigrants’ contributions in general frames a porous boundary through which most respondents can fit, given that most Americans’ are descended from immigrants within just a few generations. The belief that immigrants contribute to American society has deep roots in the national ethos: both the item’s vague temporal reference and the resonance with the trope that the United States is a “nation of immigrants” makes it easy for respondents to endorse this view, even if they are critical of some immigrants or immigration policies. The lack of increased negative affect toward Asian Americans may also reflect contingency in against whom boundaries are strengthened, perhaps reflecting the use of an insider label (“Asian Americans” rather than “Asians” or “Asian immigrants”) or the lack of national specificity (“Asian” rather than “Chinese”).

Racial triangulation theory and BIS theory converge in the expectation that groups perceived as “foreign” (Asian Americans and Latinos) will be major targets of pandemic anxiety. The negative effects of COVID‐19 priming on attitudes toward diversity and support for a pathway to citizenship are consistent with triangulation theories. That the effect was significant for white and Asian American respondents but not for African Americans, however, is inconsistent with models that posit that Asian Americans should be targets of attitude change, rather than exhibiting it themselves. Asian Americans’ responsiveness to treatment may reflect anxiety about their own status given whites’ response to pandemic threat, rather than increased xenophobia—an interpretation consistent with the group’s shift toward even more positive views of immigrants’ contributions between September and April. Finally, the absence of increased anger toward or fear of Asian Americans runs strongly counter to BIS theory’s expectations.

The BIS theory’s tenet that hostility to outgroups is a functional response to novel pathogens was also disconfirmed by the failure of real or perceived biological threat to increase xenophobic responses either through main effects or by boosting the priming effect. The most direct measure of actual health risk—county death rate at the time of the survey—had no effect on susceptibility to the experimental treatment. Another measure of vulnerability, age, did change in the predicted direction between November and April, as older people became less likely to praise immigrants’ contributions to the United States while younger people became more favorable. But age interacted with exposure to the COVID‐19 treatment in the March survey to render attitudes toward diversity more positive among older Californians.

Finally, we asked whether priming pandemic awareness would more strongly affect respondents already antagonistic to immigrants, or liberal respondents, for whom priming might activate implicit prejudice. Results were mixed. For the policy question—support for a pathway to citizenship— the treatment effect was significantly stronger on more conservative voters. By contrast, for attitudes toward diversity, treatment effects were significantly stronger for liberals. “Diversity” is a feel‐good concept, more connotative than denotative: associating it with illness may reduce its positive aura among liberals, who are most prone to embrace it, more than among political conservatives, who already take a dimmer view. By contrast, liberals’ immigration policy preferences are based on clearly articulated principles and thus less vulnerable to erosion than the more abstract concept of diversity, whereas COVID‐19 priming reinforced conservatives’ well‐established opposition to permissive immigration policies, evoking a boundary between documented and “illegal” immigrants that is more salient to conservatives than to liberals.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates qualified support for the expectation that biological threat leads affected populations to strengthen symbolic boundaries against perceived outsiders. This dynamic was evident in more negative views of policies that help undocumented immigrants and of the hazy notion of “diversity,” but not in more negative feelings toward Asian Americans in particular or immigrants in general. Furthermore, the effects varied by respondents’ ethnoracial identity and political perspective, illustrating the importance of racial differences and political predispositions in moderating the impact of pandemic threat.

Several unanticipated results open directions for further inquiry. The most striking was the wagon‐circling effect, by which Asian Americans’ and Latinos’ approval of immigrants’ contributions to the U.S.— already high in September—both became even higher during the pandemic. Because other items were not asked in September, we cannot assess how general this mechanism was, nor can we be sure that it was in response to COVID‐19. But it raises an important question: Under what conditions will U.S. citizens in ethnically marginalized communities close ranks in response to a threat and intensify their support for immigrant copanethnics, rather than distancing themselves from newcomers?

Given this finding of wagon circling over time, the negative impact of the COVID‐19 treatment on attitudes of Asian‐American respondents toward diversity, immigrants, and support for a pathway to citizenship is even more surprising. Priming brings to the fore schematic associations that may not ordinarily be activated. Priming awareness of the COVID‐19 pandemic produced ambivalence about diversity and immigration among Asian‐American respondents more than among members of other ethnoracial groups. Priming may have aroused awareness of their group’s vulnerability, producing negative feelings; or it may have led respondents to externalize the hostility their own group experienced by associating diversity and immigration with Latino migrants. Further research should explore the generality and meaning of this pattern.

Third, the failure of the COVID‐19 prime to increase anger against or fear of Asian Americans was striking given increases in hate crimes and speech and requires further exploration. It is possible that social‐desirability or self‐consistency bias affected responses. Moreover, fear and anger are usually elicited face to face, so that low self‐reports may reflect social isolation of non‐Asian respondents from Asian Americans. Nonetheless research should also test the hypothesis that elite authorization of racial invective and violence, rather than rising anti‐Asian sentiment, has fueled the increase in odious speech and behavior.

The contrast in results for attitudes toward diversity and a pathway to citizenship on the one hand, and toward immigrants’ contributions and affect toward Asian Americans calls attention to the way in which different attitudes related to social diversity evoke different intergroup boundaries, from racial difference (diversity), to difference based on legal status (pathway to citizenship), to one ethnicity vs. all others (affect toward Asian Americans). Work is needed to articulate the dimensions of difference and explore their responses to experimental manipulation and social change.

Finally, the extent of attitudinal response to disease threat depends on political and institutional factors and on the progress of the disease itself. Location and timing matter. What we know of the pandemic is constantly changing, and citizens’ understandings will depend on political and institutional responses at the national, state, and local levels. Future research should explore variation in places with different ethnoracial ecologies and political leadership, as well as tracking the impact of political events as the pandemic wears on.

APPENDIX A.

Descriptive Statistics for California Poll, September 2019

| Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrants make the United States. a worse place to live | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Latino/a/Hispanic | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Black/African American | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| White/Caucasian | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Trump approval | 2.22 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| U.S.‐Born | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| What is your age? | 49.56 | 18.04 | 18.00 | 97.00 |

| High school or less | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Some college | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| B.A. or more | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Income | 113125.18 | 103921.78 | 10000.00 | 359861.50 |

| Evangelical | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| N | 4527 |

OSF Preregistration at https://osf.io/krhec. Authors’ names are listed alphabetically, as this was a fully collaborative effort. We are grateful to Maria Abascal, Jennifer Lee, and Sociological Forum’s editor and reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

Given the extraordinary heterogeneity of the Asian‐American population, we would have liked to have been able to distinguish among attitudes toward, and attitudes of, Asian‐Americans, unnaturalized Asian immigrants, and Chinese‐Americans. For reasons discussed below, we are confident in the credibility of our findings about majority attitudes toward Asian Americans. The absence of detailed national‐origin categories does, however, complicate interpretation of Asian‐Americans’ survey responses.

In research on implicit bias, whites are perceived as most prototypically American (Devos and Banaji 2005), Blacks are second, and Latinos and Asians are “forever foreigners.” After declining for a decade, the prototypicality gap between Asian Americans and Euro‐Americans rose markedly after the pandemic struck in March 2019 (Darling‐Hammond et al. 2020).

Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Tracker, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/state‐timeline. Last accessed July 2, 2021.

The survey contained three other items with the same format as the items about affect toward Asian Americans, dealing with attitudes toward Latinos, African Americans, and whites. We omit analyses of these items because they do not illuminate the results reported here.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus‐us‐cases.html Last accessed July 7, 2021.

The highest category was transformed as per Hout (2004), p. 4, equation 2.

We omitted the partisanship measure due to multicollinearity. In preliminary analyses including partisanship, political ideology, and Trump approval, the latter two had consistent distinct and almost always significant effects, whereas partisanship effects were often insignificant.

The effects reported below for the interaction between survey condition and political beliefs are the same when using a measure of Trump approval instead of political beliefs. Interaction effects were examined in clusters (ethnoracial background) or singly (political and disease vulnerability), and significant effects were included together in a complete model (not reported here), in which they remained significant.

Evangelical faith predicted more tolerant responses on three of our four outcome variables, a result that surprised some early readers of this article. Additional analyses (available on request) reveal that the effect was a consequence of more tolerant views among Evangelical than among non‐Evangelical supporters of Donald Trump, with little difference between Evangelical and non‐Evangelical Trump detractors. This was the case even though their own ethnoracial backgrounds were not distinguishable from those of other Trump supporters.

The negative effect for Asian Americans is consistent with previous research that indicates low Asian American support for undocumented immigration, which may be associated with Latino outgroups (Tran and Warikoo 2021). Separate analyses (available upon request) revealed that support was significantly weaker among Asian American immigrants (all of whom were naturalized, given that only registered voters were surveyed) than among native born Asian Americans. (By contrast, regression results show that responses from immigrant and native born Asian‐Americans to the other items did not differ significantly, nor were treatment effects significantly different).

Contributor Information

Chelsea Daniels, Email: cpd317@nyu.edu.

Paul DiMaggio, Email: Pd1092@nyu.edu.

G. Cristina Mora, Email: cmora@berkeley.edu.

Hana Shepherd, Email: hshepherd@sociology.rutgers.edu.

REFERENCES

- Aaroe, Lene , Petersen Michael Bang, and Arceneaux Kevin. 2017. “The Behavioral Immune System Shapes Political Intuitions: Why and How Individual Differences in Disgust Sensitivity Underlie Opposition to Immigration.” American Political Science Review 111: 2: 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, Maria . 2015. “Us and Them: Black‐White Relations in the Wake of Hispanic Population Growth.” American Sociological Review 80: 4: 789–813. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, Maria & Ganter Flavien 2020. "Know it when You See it? The Qualities of the Communities People Describe as ‘Diverse' (or Not)." Working paper, NYU.

- Alba, Richard . 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority and the Expanding American Mainstream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartos, Vojtech , Bauer Michal, Cahlikova Jana, and Chytilova Julie. 2021. “COVID‐19 Crisis and Hostility Against Foreigners.” European Economic Review 137: 103818– 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Joyce and Hartmann Douglas. 2007. “Diversity in Everyday Discourse: The Cultural Ambiguities and Consequences of ‘Happy Talk’.” American Sociological Review 72: 895–914. [Google Scholar]

- Bensman, Todd . 2020. “Growing Number in Congress Demanding Answers on Covid‐19 at the Border.” Center for Immigration Studies, August 12. https://cis.org/Bensman/Growing‐Number‐Congress‐Demanding‐Answers‐Covid19‐Border.

- Blauner, Robert . 1972. Racial Oppression in America. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla‐Silva, Eduardo . 2006. Racism without Racists. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers . 2002. “Ethnicity Without Groups.” European Journal of Sociology 43: 2: 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bump, Philip . 2021. “With the Pandemic Far from Over, Texas Leaders Blame Immigrants for Spreading the Virus.” Washington Post, March 4. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/03/04/with‐pandemic‐far‐over‐texas‐leaders‐blame‐immigrants‐spreading‐virus/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020. “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Frequently Asked Questions: Reducing Stigma.” https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/daily‐life‐coping/reducing‐stigma.html Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Chen, Brian X. 2021. “The Cost of Being an ‘Interchangeable Asian’.” New York Times, June 6 (updated June 10). https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/06/business/the‐cost‐of‐being‐an‐interchangeable‐asian.html?searchResultPosition=11,

- Cisneros, J. David . 2008. “Contaminated Communities: The Metaphor of ‘Immigrant as Pollutant’ in Media Representations of Immigration.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 11: 4: 569–601. [Google Scholar]

- Darling‐Hammond, Sean , Michales Eli, Allen Amani, Chae David, Thomas Marilyn, Nguyen Thu, Mujahid Mahasin, and Johnson Rucker. 2020. “After ‘The China Virus’ Went Viral: Racially Charged Coronavirus Coverage and Trends in Bias Against Asian Americans.” Health Education & Behavior 47: 6: 870–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Michael . 1995. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African‐American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, Thierry and Banaji Mahzarin R.. 2005. “American=White?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88: 3: 447–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary . 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kagan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Drouhot, Lucas G. , Petermann Sören, Schönwälder Karen, and Vertovec Steven. 2021. “Has the Covid‐19 Pandemic Undermined Public Support for a Diverse Society? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44: 5: 877–892. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, Sunasir and Rao Hayagreeva. 2015. “Infectious Diseases, Contamination Rumors, and Ethnic Violence: Regimental Mutinies in the Bengal Native Army in 1857 India.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 129: 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild, Amy and Tynan Eileen. 1994. “Policies of Containment: Immigration in the era of AIDS.” American Journal of Public Health 84: 12: 2011–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Rene . 2017. “Do Anti‐Immigrant Laws Shape Public Sentiment? A Study of Arizona’s SB 1070 Using Twitter Data.” American Journal of Sociology 123: 2: 333–384. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, Andrew S. 2009. “A Conceptual Framework for Ordered Logistic Regression Models.” Sociological Methods and Research 38: 3: 306–347. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Erika , Eckel Sandrah, Chen Zhanghua, Li Kenan, and Gillibrand Frank. 2021. “COVID‐19 Mortality in California Based on Death Certificates: Disproportionate Impacts Across Racial/ethnic Groups and Nativity.” Annals of Epidemiology 58: 69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller, Jens and Hopkins Daniel. 2014. “Public Attitudes toward Immigration.” Annual Review of Political Science 17: 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Todd K. , Stocks Thomas, McKay Ryan, Gibson‐Miller Jilly, Levita Liat, Martinez Anton, Mason Liam, McBride Orla, Murphy Jamie, Shevlin Mark, Bennett Kate M., Hyland Philip, Karatzias Thanos, Vallières Frederique, and Bentall Richard P.. 2021. “The Authoritarian Dynamic During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Effects on Nationalism and Anti‐Immigrant Sentiment.” Social Psychological and Personality Science. Published on‐line: 10.1177%2F1948550620978023. [Google Scholar]

- Hout, Michael . 2004. “Getting the Most out of the GSS Income Measures.”. Working paper, University of California ‐ Berkeley, Survey Research Center.

- Huang, Julie Y. , Sedlovskaya Alexandra, Ackerman Joshua M., and Bargh John A.. 2011. “Immunizing against Prejudice: Effects of Disease Protection on Attitudes toward Outgroups.” Psychological Science 22: 1550–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Tiffany . 2021. “Perceived Discrimination and Intergroup Commonality Among Asian Americans.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 2: 180–200 [Google Scholar]

- Inbar, Yoel , Pizarro David, and Bloom Paul. 2009. “Conservatives are More Easily Disgusted Than Liberals.” Cognition and Emotion 23: 4: 714–725. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung, Russell , Yellow Horse Aggie J., and Cayanan Charlene. 2021. Stop AAPI Hate National Report 3/19/20 3/31/21. San Francisco: Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. https://stopaapihate.org/national‐report‐through‐march‐2021/ Accessed July 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Claire Jean . 1999. “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans.” Politics and Society 27: 1: 105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sunmin . 2021. “Fault Lines among Asian Americans: Convergence and Divergence in Policy Opinion.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 2: 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, Alan . 1994. Silent Travelers, Germs, Genes and the ‘Immigrant Menace’. NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, Alan . 2010. “Immigration, Ethnicity and the Pandemic.” Public Health Reports 125: Supplement 3: 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer and Ramakrishnan Karthick. 2021. “From Research Scarcity to Research Plenitujde for Asian Americans.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 2: 1–20.34729421 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer and Yadav Monika. 2020. “The Rise of Anti‐Asian Hate in the Wake of Covid‐19.” Items: Insights from the Social Sciences (Social Science Research Council), May 21. https://items.ssrc.org/covid‐19‐and‐the‐social‐sciences/the‐rise‐of‐anti‐asian‐hate‐in‐the‐wake‐of‐covid‐19/.

- Lee, Jennifer and Zhou Min. 2015. The Asian‐American Achievement Paradox. NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yao and Nicholson Harvey L.. 2020. “When ‘Model Minorities’ Become ‘Yellow Peril’: Othering and the Racialization of Asian Americans in the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Sociology Compass 2021: 10.1111/soc4.12849. Accessed July 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani, Anandi , Mullainathan Sendhil, Shafir Eldar, and Zhao Jiaying. 2013. “Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function.” Science 341: 976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Josh . 2020. “FBI Warns of Potential Surge in Hate Crimes against Asian Americans amid Coronavirus.” ABC News, March 27. https://abcnews.go.com/US/fbi‐warns‐potential‐surge‐hate‐crimes‐Asian.Americans/story?id=69831920

- Markel, Howard . 1999. Quarantine: East European Jewish Immigrants and the New York City Epidemics of 1892. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]