Abstract

The LiPA MYCOBACTERIA (Innogenetics NV, Ghent, Belgium) assay was used to identify mycobacterial isolates using culture fluid from positive BACTEC 12B bottles. The LiPA method involves reverse hybridization of a biotinylated mycobacterial PCR fragment, a 16 to 23S rRNA spacer region, to oligonucleotide probes arranged in lines on a membrane strip, with detection via biotin-streptavidin coupling by a colorimetric system. This system identifies Mycobacterium species and differentiates M. tuberculosis complex, M. avium-M. intracellulare complex, and the following mycobacterial species: M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. kansasii, M. chelonae group, M. gordonae, M. xenopi, and M. scrofulaceum. The mycobacteria were identified in the laboratory by a series of tests, including the Roche AMPLICOR Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) test, the Gen-Probe ACCUPROBE, and a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis of the 65-kDa heat shock protein gene. The LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay detected 60 mycobacterium isolates from 59 patients. There was complete agreement between LiPA and the laboratory identification tests for 26 M. tuberculosis complex, 9 M. avium, 3 M. intracellulare complex, 3 M. kansasii, 4 M. gordonae, and 5 M. chelonae group (all were M. abscessus) isolates. Three patient samples were LiPA positive for M. avium-M. intracellulare complex, and all were identified as M. intracellulare by the PCR-RFLP analysis. Seven additional mycobacterial species were LiPA positive for Mycobacterium spp. (six were M. fortuitum, and one was M. szulgai). The LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay was easy to perform, and the interpretation of the positive bands was clear-cut. Following PCR amplification and gel electrophoresis, the LiPA assay was completed within 3 h.

Although more than 70 mycobacterial species have been described, relatively few of them are strictly pathogenic for man or animals (19). While Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains are still responsible for the majority of Mycobacterium infections worldwide, opportunistic infections due to mycobacteria other than tuberculosis (MOTT) have been on the increase, mainly as a consequence of the AIDS epidemic (8, 21, 23). Among the mycobacterial species often implicated in MOTT infections are M. avium-M. intracellulare complex, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, M. kansasii, and M. xenopi (8, 19, 33). M. gordonae does not usually cause human infection but is often encountered as a contaminant in clinical samples, and discrimination from pathogenic species is a relevant diagnostic issue (4).

The use of liquid cultures in the clinical laboratory improves the ability to detect the growth of mycobacteria (14, 17, 26). The radiometric method (BACTEC; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) is a fast and sensitive liquid culture system (20). When a BACTEC bottle is detected as positive, confirmation of the presence of acid-fast bacilli is done by acid-fast staining and the broth is plated on solid media. M. tuberculosis complex can be identified rapidly by a variety of nucleic acid amplification procedures that are commercially available (9, 30, 32). Rapid identification of MOTT isolates growing on solid media can be done by techniques such as thin-layer chromatography (11), gas-liquid chromatography (30), high-performance liquid chromatography (10), and analysis with DNA probes (18). Recently developed molecular methods, such as DNA probe tests (25) and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (28, 29), offer identification of this complex group of organisms from a positive liquid culture medium prior to detection of growth on solid media (3, 7). DNA probes (ACCUPROBE; Gen-Probe, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) can be used for the rapid identification of M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. intracellulare, M. gordonae, and M. kansasii from solid culture and directly from liquid culture systems (2, 3, 6, 7, 16, 26). Unfortunately, the DNA probes are available for a limited number of species, and without colonial morphology to guide probe selection, testing with multiple probes may be necessary. An algorithm based on growth rate in the BACTEC 12B bottle and a fluorochrome smear quantitation to guide DNA probe selection has been reported (16). PCR-RFLP analysis is a reliable method for identification of MOTT, encompassing identification of the entire range of organisms normally isolated in a clinical laboratory (28, 29). The LiPA MYCOBACTERIA test offers identification of a limited number of common mycobacterial species by PCR amplification of the 16 to 23S rRNA spacer region of Mycobacterium species followed by hybridization of the biotinylated amplified DNA product with 14 specific oligonucleotide probes. The specific probes are immobilized as parallel lines on membrane strips. The objective of this study was to evaluate the LiPA MYCOBACTERIA (Innogenetics NV, Ghent, Belgium) assay for identification and differentiation of specific mycobacterial species from positive BACTEC 12B liquid cultures. The assay was evaluated for specificity, ease of use, and interpretation of results in a routine clinical laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture and identification.

Respiratory specimens submitted for culture were decontaminated with an equal volume of 5% N-acetyl cysteine-NaOH and concentrated by centrifugation (24). The sediment was used to prepare two smears and to inoculate a selective 7H11 agar plate and a BACTEC 12B bottle (Becton Dickinson). BACTEC 12B bottles were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and monitored for growth for 6 weeks with a BACTEC 460 instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions. When the growth index of a bottle reached ≥50, a smear was prepared to confirm the presence of acid-fast organisms and the liquid medium was subcultured onto a blood agar and a 7H11 agar plate. Isolates of mycobacteria growing on solid media were identified by DNA probes (ACCUPROBE; Gen-Probe, Inc.) for M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. gordonae, and M. kansasii or by conventional biochemical tests performed according to standard protocols (13, 19).

AMPLICOR M. tuberculosis PCR test.

Respiratory specimens submitted for culture that were acid-fast organism smear positive were processed for PCR directly from the decontaminated concentrated specimen according to the instructions of the package insert for the AMPLICOR M. tuberculosis test (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.), as previously described (5). In addition, PCR testing was also performed from positive BACTEC 12B bottles using 0.5 ml of the culture fluid concentrated by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min in a 1.5-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge tube. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer and processed in the same way as direct clinical specimens for the remainder of the procedure. All manipulations of positive smear specimens and BACTEC 12B bottles were performed in a biological safety hood. PCR amplification and detection were performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay.

Specimens were prepared for PCR amplification by removal of 0.2 ml from BACTEC 12B bottles. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and placed in a 95°C heat block for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 s. The tubes were placed in a −20°C freezer for 30 min. Upon thawing, samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 s. A reaction mix of 40 μl was prepared from the supplied amplification mixture containing deoxynucleoside triphosphates, biotinylated primers, and thermostable DNA polymerase, to which 10 μl of the processed specimen was added. The PCR was done in a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermocycler with the following amplification profile: 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles. The presence of the amplified product was verified by electrophoresis of 10 μl of the amplified product in a 2.0% agarose gel followed by staining with ethidium bromide. The expected size of the amplicon was a single band with a length of 400 to 550 bp. For hybridization, a 10-μl sample of the amplified product was denatured in the hybridization trough, followed by addition of the hybridization solution provided in the assay kit and the membrane strip. The hybridization solution was prewarmed to 62°C. The tray of strips was placed in a 62°C shaking water bath (80 rpm) with a lid and incubated for 30 min (model Gemini II incubator; Robbins Scientific, Sunnyvale, Calif.). After hybridization, two stringent washes were done at 62°C. The remainder of the procedure was done at room temperature using a rotary shaker at 80 rpm. Each strip was washed twice for 1 min using 2.0 ml of rinse solution, followed by addition of alkaline phosphatase-streptavidin conjugate solution for 30 min. Each strip was washed twice with rinse solution and once with 2.0 ml of the substrate buffer prior to incubation with the substrate (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium) solution for 30 min while being shaken. The color development was stopped by washing the strips twice in 2.0 ml of distilled water with shaking for 3 min. After hybridization and detection, each strip was aligned along the reading chart for interpretation using a green line at the top of the strip for reference.

PCR-RFLP analysis.

The PCR-RFLP analysis to identify the Mycobacterium species was done by PCR amplification of a 439-bp segment of the mycobacterial 65-kDa heat shock protein gene (27, 28). Specimens from positive BACTEC 12B bottles were processed for PCR using the same method as that used for the LiPA assay. The PCR was done in a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermocycler with the following amplification profile: 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 35 cycles. BstEII and HaeII (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) enzyme digestions of the amplification product were performed, and restriction fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis of a 3.0% gel composed of 2.0% high-resolution agarose (Sigma) and 1.0% routine-use agarose (Sigma). The molecular size standard (MspI-digested pUC18; Sigma) was placed in the gel every four lanes to reduce migration-related errors in interpretation of fragment sizes. Photographs were taken of the gels after ethidium bromide staining and were analyzed visually to determine the number and the sizes of the fragments present. Isolates were identified using a published PCR-RFLP analysis algorithm (28, 29). A website (www.hospvd.ch/prasite) was also used for pattern analysis and species identification.

RESULTS

LiPA PCR amplification of the 16 to 23S rRNA.

Amplified product was detected in 57 of 60 patient samples after the first amplification. The three negative samples were positive when they were diluted 1:2 or 1:10 prior to amplification. The amplified product yielded a clear band in the range of 400 to 500 bp.

LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay identification.

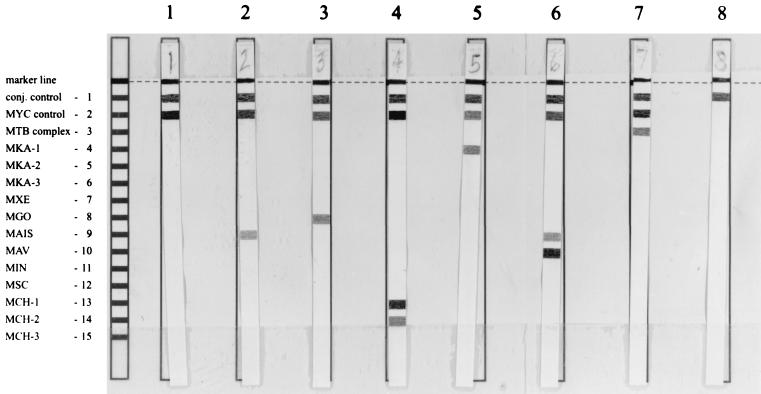

Figure 1 shows a representative sampling of results of the assay. Each line number which was positive on the LiPA MYCOBACTERIA strip was noted and used to determine the Mycobacterium species by using the probe alignment guide included in the kit shown on the left side in Fig. 1. The conjugate control line and Mycobacterium species positive control line must be positive for a valid result. The LiPA assay identified 60 mycobacterium isolates from 59 patients (Table 1). One patient sample produced amplified product of the correct size but was negative in the LiPA assay.

FIG. 1.

Representative examples of results of the LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay. The positions of the conjugate (conj.) control, Mycobacterium genus-positive control, and the 13 specific probes are shown on the left. The marker line at the top of the strip is used for orientation of the strip for analysis. Lanes: 1, M. fortuitum; 2, M. avium-M. intracellulare complex; 3, M. gordonae; 4, M. chelonae; 5, M. kansasii; 6, M. avium; 7, M. tuberculosis; 8, conjugate control without Mycobacterium DNA present. MYC, Mycobacterium complex; MTB, M. tuberculosis complex; MKA, M. kansasii; MXE, M. xenopi; MGO, M. gordonae; MAIS, M. avium-M. intracellulare complex; MAV, M. avium; MIN, M. intracellulare; MSC, M. scrofulaceum; MCH, M. chelonae.

TABLE 1.

Line probe assay results and identification of mycobacterial species by PCR and RFLP analysis of 60 patient samplesa

| Sample | Smearb | GIc | Gel resultd | LIPA result | LIPA ID | Other testinge | RFLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 2 | 1+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 3 | Neg | 999 | Smear 480–550 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 4 | 2+ | 428 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 5 | 3+ | 193 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 6 | Neg | 211 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 7 | 4+ | 533 | Clear 400, weak 850 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 8 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 9 | Neg | 783 | Clear 400, weak 850 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MSZ biochem ID | MSZ |

| 10 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MGO | M. gordonae | MGO probe | MGO |

| 11 | Neg | 71 | Clear 400, weak 850 | MYC, MGO | M. gordonae | MGO probe | MGO |

| 12 | Neg | 303 | Clear 400, weak clear 500 | MYC, MKA-1 | M. kansasii | MKA probe | MKA |

| 13 | 2+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MKA-1 | M. kansasii | MKA probe | MKA |

| 14 | Neg | 999 | Clear 450 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 15 | Neg | 205 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS | MAIS complex | MIN probe | MIN |

| 16 | Neg | 61 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MIN | M. intracellulare | MIN probe | MIN |

| 17 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 18 | 3+ | 622 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 19 | 2+ | 999 | Smear 450–500 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 20 | Neg | 653 | Clear 400 | MYC, MGO | M. gordonae | MGO probe | MGO |

| 21 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400, clear 280 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 22 | Neg | 999 | Smear 400–550 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 23 | Neg | 999 | Smear 400–550 | MYC, MCH-1, MCH-2 | M. chelonae group III | MCH group and MFO biochem ID | MAB and MFO |

| 24 | Neg | 999 | Smear 400–550 | MYC, MCH-1, MCH-2 | M. chelonae group III | MCH group biochem ID | MAB |

| 25 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 26 | Neg | 999 | 450, smear 480–520 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 27 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 28 | Neg | 999 | Smear 400–450 | MYC, MAIS, MIN, MCH-1, MCH-2 | M. intracellulare and M. chelonae III | MIN probe and MCH group biochem ID | MIN and MAB |

| 29 | Neg | 711 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 30 | 3+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 31 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MCH-1, MCH-2 | M. chelonae group III | MCH group biochem ID | MAB |

| 32 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 33 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 34 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MIN | M. intracellulare | MIN probe | MIN |

| 35 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MCH-1, MCH-2 | M. chelonae group III | MCH group biochem ID | MAB |

| 36 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 37 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 38 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 39 | 3+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 40 | 2+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 41 | 3+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 42 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MGO | M. gordonae | MGO probe | MGO |

| 43 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400, smear 450–520 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 44 | Neg | 999 | Clear 460 | MYC | Mycobacterium species | MFO biochem ID | MFO |

| 45 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 46 | 1+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 47 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 48 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS, MAV | M. avium | MAV probe | MAV |

| 49 | Neg | Neg | Clear 380, 550, smear 400+ | Conjugate control only | Nonmycobacterial | No mycobacteria isolated | |

| 50 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 51 | 1+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MAIS | MAIS complex | MIN probe | MIN |

| 52 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 53 | Neg | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MKA-1 | M. kansasii | MKA probe | MKA |

| 54 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 55 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 56 | 4+ | 999 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 57 | 2+ | 548 | Smear 450–500 | MYC, MAIS | MAIS complex | MAIS probe | MIN |

| 58 | 3+ | 34 | Clear 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 59 | 3+ | 66 | Weak 400 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

| 60 | 3+ | 23 | Weak 450 | MYC, MTB | M. tuberculosis | MTB PCR | MTB |

MYC, Mycobacterium species; MTB, M. tuberculosis; MGO, M. gordonae; MAIS, M. avium-M. intracellulare complex; MIN, M. intracellulare; MAV, M. avium; MKA-1, M. kansasii group I; MCH-1, M. chelonae groups I, II, III, and IV; MCH-2, M. chelonae group III; MFO, M. fortuitum; MSZ, M. szulgai; MAB, M. abscessus; ID, identification; biochem, biochemical testing.

Smear, concentrated acid-fast organism smear negative (Neg, negative; 1+ to 4+, positive).

GI, growth index of BACTEC 12B bottle.

Appearance and size(s) of band(s) (in base pairs).

Other testing, method of identification.

There was complete agreement between the LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay and the laboratory identification tests for 26 M. tuberculosis, 9 M. avium, 3 M. intracellulare, 3 M. kansasii, 4 M. gordonae, and 5 M. chelonae group (all were M. abscessus) isolates from positive BACTEC 12B bottles (Table 2). In one patient sample, bands were present for both M. intracellulare and M. chelonae. This patient has a history of cultures positive for both organisms, and the PCR-RFLP yielded the same identification. There were six isolates of M. fortuitum and one isolate of M. szulgai; all were positive for the Mycobacterium species probe, which identified them as mycobacterial species. The assay is not capable of species identification for M. fortuitum and M. szulgai.

TABLE 2.

Summary of mycobacterial species identification by all methods tested

| Organism | No. of isolates | No. of isolates positive by:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiPA | M. tuberculosis PCR | Probe | RFLP analysis | Biochemical testing | ||

| M. tuberculosis | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | ||

| M. kansasii | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| M. avium-M. intracellulare complex | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | ||

| M. avium | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||

| M. intracellulare | 6 | 3b | 5c | 6 | ||

| M. gordonae | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| M. fortuitum | 7 | 7de | 7 | 7 | ||

| M. chelonae groupa | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| M. szulgai | 1 | 1d | 1 | 1 | ||

Includes M. chelonae and M. abscessus.

All six were positive by the M. avium-M. intracellulare complex probe.

All were positive by the M. avium-M. intracellulare complex probe (ACCUPROBE).

Identified as Mycobacterium species only.

One sample was positive for two different species by culture, but we were unable to determine if two species were present in the LiPA samples.

The nine M. avium isolates were reactive with the M. avium-M. intracellulare complex probe (M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. malmoense, and M. haemophilum) and the M. avium probe (M. avium, M. paratuberculosis, and M. silvaticum). The three M. intracellulare isolates were reactive with the M. avium-M. intracellulare probe and the M. intracellulare probe. The four M. gordonae isolates were reactive with the M. gordonae probe. The three M. kansasii isolates were all reactive with the M. kansasii group I probe (MKA-1) and negative with the MKA-2 (group II) and MKA-3 (groups III, IV, and V and M. gastri) probes. M. kansasii isolates are divided into five groups based on data derived from 16 to 23S rRNA spacer nucleotide sequences (1). The MKA-1 probe reacts with M. kansasii type I, the most frequent M. kansasii isolate from human sources worldwide (1). M. kansasii group II, which is detected by the MKA-2 probe, is isolated from both humans and the environment and is characterized by negative hybridization in the ACCUPROBE assay. M. kansasii groups III, IV, and V have rarely been isolated from humans but have been found in environmental samples (1). The five M. chelonae solates were reactive with the MCH-1 probe (M. chelonae groups I, II, III, and IV) and the MCH-2 probe (M. chelonae group III). M. chelonae isolates are divided into four genotypical clusters based on 16 to 23S rRNA nucleotide sequences (22). The MCH-1 probe reacts with all four clusters, and the MCH-2 probe reacts with cluster III isolates, which encompass M. chelonae and M. abscessus. The PCR-RFLP analysis identified the five M. chelonae isolates as M. abscessus. One patient isolate that was identified as an M. chelonae group isolate by the LiPA assay and as M. abscessus by PCR-RFLP analysis had been identified as M. fortuitum by conventional methods. Closer inspection found the culture to contain two organisms, M. fortuitum and M. abscessus. We were unable to determine if both species were detected in the LiPA assay since a specific probe for M. fortuitum is not available and the reactivity with the Mycobacterium species probe may have been due to either or both organisms. The presence of both organisms was confirmed by PCR-RFLP analysis of two different colonies from the 7H11 agar plate.

DISCUSSION

The differentiation of species of Mycobacterium has traditionally been done by evaluation of growth characteristics and biochemical testing. Rapid methodologies such as those using DNA probes are limited by the number of available commercial probes. In our laboratory, 50% of the acid-fast isolates recovered from specimens are not MOTT; therefore, a comprehensive rapid detection method capable of identifying multiple species of mycobacteria in a single test would have a significant impact. This paper describes the evaluation of a practical method for the identification of mycobacterial DNA amplified by PCR from acid-fast-bacillus-positive BACTEC 12B bottles. The LiPA line probe assay employs a reverse hybridization reaction of biotin-labeled amplified DNA with specific oligonucleotide probes fixed as parallel lines on a membrane strip. This method was compared to a PCR-RFLP procedure that is capable of differentiating 28 species of clinically encountered mycobacteria (28, 29).

The LiPA MYCOBACTERIA test was easy to perform, and the interpretation of the results was clear-cut and objective. The LiPA assay identified 60 mycobacterium isolates from 59 patients. Six of seven of the isolates were M. fortuitum and one was M. szulgai, for which the assay does not have specific probes; therefore, they were identified as Mycobacterium species in the LiPA assay. The assay correctly identified 50 of 53 isolates to the species level. The remaining three isolates were identified as M. avium-M. intracellulare group isolates by LiPA and were identified as M. intracellulare by PCR-RFLP analysis and with the ACCUPROBE DNA probe. One culture was found to contain two organisms by RFLP analysis, M. fortuitum and M. abscessus. M. abscessus was correctly identified in the LiPA assay with the M. chelonae group probes. Since the presence of M. fortuitum would not be distinguishable from M. chelonae, we cannot determine whether both organisms were amplified and detected in the assay.

In a smaller study of 27 specimens from liquid culture (S. A. Watterson, B. A. Hussein, and F. A. Drobniewski, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1999, abstr. U-29, p. 639, 1999), there was agreement with standard methods of identification for 26 of 27 of the isolates. The discrepant sample was identified by standard biochemical methods as M. fortuitum but as M. chelonae group III by the LiPA assay. However, a subsequent sample from the same patient was identified as M. chelonae by standard biochemical methods.

The main advantage of LiPA compared to testing with DNA probes is that LiPA can identify a wide range of species in a single assay instead of a technician performing a different test for each species or waiting for growth on solid media to guide the choice of DNA probe. The PCR-RFLP method has the same advantage over the use of DNA probes, although the PCR-RFLP results require more expertise to interpret than the LiPA results. It was not surprising that the three M. kansasii isolates were all reactive with the M. kansasii group I probe (MKA-1) and negative with the probes for group II (MKA-2) and group III, IV, and V and M. gastri (MKA-3) isolates since M. kansasii group I represents the most common clinical isolate from humans (1). Group I has a PCR-RFLP pattern distinguishable from those of other M. kansasii groups, and in our laboratory all clinical isolates have been group I.

In our laboratory, 50% of mycobacterial isolates in 1998 were M. tuberculosis; the majority of isolates were identified by an M. tuberculosis complex PCR assay. An additional 34.7% of our isolates were identified using DNA probes for M. avium-M. intracellulare complex (29.7%), M. kansasii (3.3%), and M. gordonae (1.7%). The LiPA assay was able to identify these isolates directly from the positive BACTEC 12B bottles with a single assay and could also identify M. chelonae, which comprised 5.7% of our isolates. In total, the LiPA assay could have identified 90.6% of our isolates to the species level (1998 data). The remaining 9.4% of isolates in our lab are composed mainly of miscellaneous organisms, including M. fortuitum, for which the LiPA assay does not have a specific probe. In conclusion, we found the LiPA MYCOBACTERIA assay to be an easy test to perform in the clinical setting and one that provides identification of a large variety of mycobacterial species in a single test. As yet, the cost of the assay has not been set by the manufacturer (Innogenetics NV).

The line probe assay technology has also been used for detection of mutations in the rpoB gene of M. tuberculosis that confer resistance to rifampin (12). The rate of concordance with phenotypic rifampin susceptibility testing results was 92.2%. Another application of the line probe assay is to detect and identify human papillomavirus (HPV) strains using a strip with 28 specific probes for each of the 25 HPV genotypes (15). Since HPV cannot be cultured efficiently, diagnosis of HPV infection is based on cytology and molecular tools, which makes this organism a perfect candidate for this type of assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcaide F, Richter I, Bernasconi C, Springer B, Hagenau C, Schulze-Röbbecke R, Tortoli E, Martín R, Böttger E C, Telenti A. Heterogeneity and clonality among isolates of Mycobacterium kansasii: implications for epidemiological and pathogenicity studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1959–1964. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.1959-1964.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badak F Z, Goskel S, Sertoz R, Nafile B, Ermertcan S, Cavusoglu C, Bilgic A. Use of nucleic acid probes for identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from MB/BacT bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1602–1605. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1602-1605.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Body B A, Warren N G, Spicer A, Henderson D, Chery M. Use of Gen-Probe and Bactec for rapid isolation and identification of mycobacteria. Correlation of probe results with growth index. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:415–420. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan J, McKitrick J C, Klein R S. Mycobacterium gordonae in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:400. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-3-400_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Amato R F, Wallman A A, Hochstein L H, Colaninno P M, Scardamaglia M, Ardila E, Ghouri M, Kim K, Patel R C, Miller A. Rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis by using Roche AMPLICOR Mycobacterium tuberculosis PCR test. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1832–1834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1832-1834.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellner P D, Kiehn T E, Cammarata R, Hosmer M. Rapid detection and identification of pathogenic mycobacteria by combining radiometric culture and nucleic acid probe methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1349–1352. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.7.1349-1352.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans K D, Nakasone A S, Sutherland P A, de la Maza L M, Peterson E M. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare directly from primary BACTEC cultures by using acridinium-ester-labeled DNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2427–2431. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2427-2431.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falkinham J O., III Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculosis mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:177–215. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamboa F, Fernandez G, Padilla E, Manterola J M, Lonca J, Cardona P J, Matas L, Ausina V. Comparative evaluation of initial and new versions of the Gen-Probe amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:684–689. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.684-689.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glickman S E, Kilburn J O, Butler W R, Ramos L S. Rapid identification of mycolic acid patterns of mycobacteria by high-performance liquid chromatography using pattern recognition software and a Mycobacterium library. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:740–745. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.740-745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hines M E, II, Frazier K S. Differentiation of mycobacteria on the basis of chemotype profiles using matrix solid-phase dispersion and thin-layer chromatography. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:610–614. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.610-614.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirano K, Abe C, Takahashi M. Mutations in the rpoB gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated mostly in Asian countries and their rapid detection by line probe assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2663–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2663-2666.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent P T, Kubica G P. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirihara J M, Hillier S L, Coyle M B. Improved detection times for Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis with the BACTEC radiometric systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:841–845. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.5.841-845.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleter B, van Doorn L, Schrauwen L, Molijn A, Sastrowijoto S, ter Schegget J, Lindeman J, ter Harmsel B, Burger M, Quint W. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2508–2517. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2508-2517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metchock B, Diem L. Algorithm for use of nucleic acid probes for identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis from BACTEC 12B bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1934–1937. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1934-1937.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan M A, Horstmeier C D, DeYoung D R, Roberts G D. Comparison of radiometric method (BACTEC) and conventional culture media for recovery of mycobacteria from smear-negative specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:384–388. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.384-388.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musial C E, Tice L S, Stockman L, Roberts G D. Identification of mycobacteria from culture by using the Gen-Probe Rapid Diagnostic System for Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2120–2123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2120-2123.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolte F S, Metchock B. Mycobacterium. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfyffer G E, Welscher H M, Kissling P, Cieslak C, Casal M J, Gutierrez J, Rusch-Gerdes S. Comparison of the Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) with radiometric and solid culture for recovery of acid-fast bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:364–368. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.364-368.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portaels F. Epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Dermatol. 1996;13:207–222. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portaels F, de Rijk P, Jannes G, Lemans R, Mijs W, Rigouts L, Rossau R. The 16S–23S rRNA spacer, a useful tool for taxonomical and epidemiological studies for the M. chelonae complex. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1996;77(Suppl. 1):17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozniak A L, Uttley A H C, Kent R J. Mycobacterium avium complex in AIDS: who, when, where, why and how? Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser. 1996;25:40S–46S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratnam S, Stead F A, Howes M. Simplified acetylcysteine-alkali digestion-decontamination procedure for isolation of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1428–1432. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.8.1428-1432.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reisner B S, Gatson A M, Woods G L. Use of Gen-Probe AccuProbes to identify Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Mycobacterium kansasii, and Mycobacterium gordonae directly from BACTEC TB broth cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2995–2998. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2995-2998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts G D, Goodman N L, Heiferts L, Larsh H W, Lindner T H, McClatchy J K, McGinnis M R, Siddiqi S H, Wright P. Evaluation of the BACTEC radiometric method for recovery of mycobacteria and drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from acid-fast smear-positive specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:689–696. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.3.689-696.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schinnick T. The 65-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1080–1086. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1080-1088.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor T B, Patterson C, Hale Y, Safranek W W. Routine use of PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of mycobacterium growing in liquid media. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:79–85. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.79-85.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telenti A, March F, Bald M, Badly F, Bottger E, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by PCR and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tisdall P A, Roberts G D, Anhalt J P. Identification of clinical isolates of mycobacteria with gas-liquid chromatography alone. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;10:506–514. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.4.506-514.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tortoli E, Lavinia F, Simonetti M T. Evaluation of a commercial ligase chain reaction kit (Abbott Lcx) for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2424–2426. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2424-2426.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vuorinen P, Miettinen A, Vuento R, Hällstrom O. Direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory specimens by Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct Test and Roche Amplicor Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Test. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1856–1859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1856-1859.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wayne L G, Sramek C., II Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1–25. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]