ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Children are expected to adhere to the recommended physical activity (PA) dose of 60 minutes per day and minimize sedentary behaviors (SB) to stray away from the cardio‐metabolic disease risk. However, there is a lack of review of current evidence pointing to the negative physical health effects of the Covid‐19 lockdown, with its barriers and facilitators for effective PA implementation in children aged 3 to 13.

METHODS

Two independent authors conducted an extensive search on five peer‐reviewed journal databases for the studies examining changes in PA or SB in children and the potential barriers during Covid‐19 lockdown.

RESULTS

Of 1039 studies initially screened, only 14 studies were included. Ninety‐three percent of the studies were cross‐sectional surveys. A 34% reduction in PA was noted while SB, including screen time, increased by 82%. Our review identified potential barriers to the effective implementation of PA behaviors in children at four levels: individual, family, school, and government policies.

CONCLUSIONS

A moderate reduction in PA and high SB in children during lockdown was linked with obstacles at the individual, family, school, and political levels. Stakeholders should consider the above barriers when designing and implementing interventions to address low PA and SB practices.

Keywords: children, physical activity, sedentary behavior, screen time, school, Covid‐19

Ever since the novel Coronavirus 2019 (Covid‐19) started infecting people by the end of 2019, the extent of the spread and the associated morbidity has been phenomenal. While the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid‐19 as a public health emergency on March 11, 2020, the Covid‐19 infection continues to threaten human lives with more than 0.17 billion confirmed cases and 3.46 million deaths. 1 Global governments have enforced protective measures including a ban on social gatherings, the closure of recreational and sports facilities, closed schools, and workplaces to mitigate the spread of Covid‐19. 2 Although viewed as protective measures to slow down the spread of the infection, contemporary evidence argues that the above preventive measures in this unprecedented situation, could reduce children's physical activity (PA) and amplify sedentary behaviors (SB) considerably.

According to WHO recommendations, the children (aged 5‐17 years) should spend at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous‐intensity physical activity (MVPA) daily for at least 3 to 4 times a week and minimize SB in everyday activities. 3 Epidemiological studies show that children who met the recommended MVPA have considerably a low cardiometabolic disease risk, 4 appreciable executive functions, and gross motor skills. 5 In contrast, SB, such as long screening time, has adverse effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive functions in children and adolescents. 6 Nonetheless, a high SB can reduce the health benefits of the daily accumulated 30–60 minutes MVPA. Therefore, limiting SB while maintaining recommended PA can combat cardiovascular disease risks and cognitive decline in children and adolescents. 7

The accumulating evidence showed low PA and high SB in children and adolescents due to restrictions on exercise amenities, access to parks, and social gatherings during the Covid‐19 pandemic. 8 In addition, school closings have reduced game time, which was used to be accumulated during planned physical education classes, playing time with peers during recess breaks, active or passive driving time to school, integrated play activities in the classroom, and leisure hour playtime after school hours. 9 In addition, virtual classrooms and substantial recreational screen time due to social isolation, online chatting, and involving in social media use have substantially increased SB and snacking time in children and adolescents. 10 The significant amount of SB in combination with low PA can increase the risk of chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and cognitive decline. 10 , 11 However, there is no pooled evidence to demonstrate the epidemiology of PA and SB in children during the Covid‐19 lockdown.

Individual factors (motivation, self‐determination, body image), interpersonal factors (peer‐group relationship, parental role model, family conflicts), and environmental factors (access to amenities, town planning, institutional guidelines, rewards, cues, and economic cost) are considered to determine the PA and SB in children and adolescents 12 , 13 The personal, socio‐cultural and environmental determinants mentioned above should be taken into account when designing interventions (intervention mapping) and later when implementing public health interventions. 14 We carried out a scoping review to deliberately recognize the impact of the ongoing pandemic and the determinants (personal, socio‐cultural, and environmental) on PA and SB in children aged 3 to 13 years.

METHODS

The present review followed the framework proposed by Arksey & O'Malley to reinforce the rigor of the review methodology. 15 It consists of five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies to answer each specific topic within the research question; (3) study selection; (4) charting data; (5) summarizing and reporting of the results.

Identifying the Research Question

The concepts, target population, and outcomes of interest from the existing evidence were reviewed and drafted two main research questions for the present scoping review. The target population includes children of age group 3 to 13 years. The research question and the outcome of interest are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research Question and the Signaled Outcomes of Interest (Determinants of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Reviewed)

| Research Question | Outcome of Interest |

|---|---|

| 1. Do COVID‐19 restrictions have any influence on physical activity in children? |

|

| 2. What factors might influence children's physical activity or sedentary behaviors due to COVID‐19 restrictions? |

|

Abbreviations: PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behavior.

Identifying Relevant Studies

Search strategies

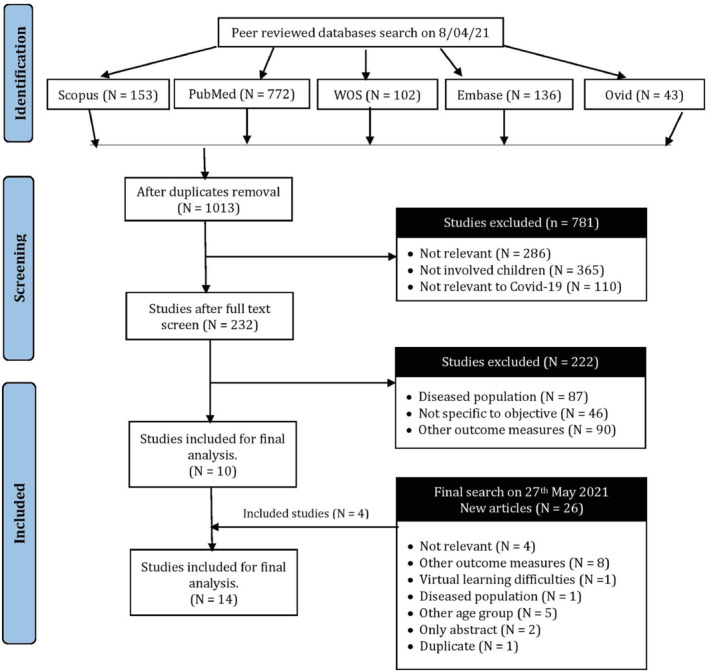

We administered a systematic search in five peer‐reviewed journal databases (Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) for potential studies investigating the PA and SB changes in children during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The search string was developed to capture the studies widely as far as possible by the two authors (MRA and BC) and senior librarian who had at least 5 years of establishing a comprehensive literature search. The search was conducted for studies published between December 2019 and May 2021. The following MeSH terms were used: “Corona pandemic,” “Corona Virus – 19”, Covid‐19, “physical activity,” “sedentary behavior,” “screen time,” exercise, “outdoor games,” “playing games,” children, child, youth, and schools. Necessary Boolean operators “AND,” “OR,” “NOT” with wild cards were added appropriately. The references cited in the studies included were also looked for possible inclusion in the review. The initial search was conducted on 8th April 2021, and the final search was performed on 27th May 2021 for any missed studies. The study flow with the reasons for exclusion is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of Search, Screen, and Inclusion of Potential Studies in the Review. WOS – Web of Science

Study selection

The primary reviewer (MR) screened for the eligible studies based on priori determined inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review. When found appropriate, the lead author downloaded the full‐text articles, and two reviewers (MR & BC) independently assessed the studies for possible inclusion in the review. All disagreements were resolved amicably between the authors.

Articles were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) potential studies should have examined PA or SB in children during COVID–19; (2) the studies should have involved the healthy children aged 3 to 13 years; (3) studies conducted between December 25, 2019 till April 8, 2021; (4) studies of any type (cross‐sectional, observational, cross over or randomized controlled trials and reviews to allow for broader coverage of studies; (5) should be published in English. Studies that included a population with any previous history of chronic illness with limited PA and determinants unrelated to Covid‐19 were excluded. Additional studies published as a protocol or languages other than English were excluded from the review. We followed the PECOTS framework for the inclusion and exclusion of the study. Table 2 illustrates the PECOTS framework and potential eligibility criteria used in this review.

Table 2.

Study Characteristics and Eligibility Criteria of the Potential Studies

| Study Characteristics | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) |

(1) Parents/guardians/caregivers of children aged 3‐13 years. (2)Teachers dealing with the Physical education of children. |

Children more than 13 years. Children with chronic conditions including obesity, congenital heart diseases, and obesity that limit PA participation. |

| Exposures (E) | COVID‐19 restrictions in children affecting PA. |

Studies only demonstrating the pathogenesis of COVID‐19. Studies that investigated only pharmacological management alone. COVID combined with dietary and vitamin deficiencies, and so on. |

| Outcomes (O) | Physical activity and sedentary behaviors in children during COVID ‐19 lockdown. | Diet and psychological outcomes such as depression and stress, academic performance and wellbeing reported. |

| Time frame (T) | 25th December 2019 to 27th May 2021 | Any studies out of the priori time frame |

| Study type (S) | Any study designs (cross‐sectional, single‐arm pre‐post, longitudinal, or cohort) reporting PA and COVID ‐19 lockdown in children | Protocol‐based or conference abstracts |

Abbreviations: PA – Physical activity; SB – Sedentary behavior.

Charting the Data

The primary authors (MR) extracted the qualitative data and determinants using a bespoke data extraction form, and the co‐author (BC) independently verified the data gleaned by the primary author (MR). The data extraction sheet had the following components: author, year, study design, the objective of the study, SB or PA measurement (intensity, type, frequency, and duration), determinants (personal socio‐cultural and environmental) related to the SB or PA during Covid‐19 and other study results. Figure 1 illustrates the studies screened and included in the review. Table 3 illustrates the study characteristics, the PA or SB change during Covid‐19, and the determinants that influence the PA or SB.

Table 3.

Study characteristics, physical activity and sedentary behavior changes and the influencing factors

| Author, Year | Location | Design | Objectives | Participants | PA/SB Measurement | Factors Influencing PA. | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al. 18 | Georgia (Europe) | Cross‐sectional study | To explore the adolescent's knowledge about Covid‐19 and the behavior change. | Adolescents of 9th to 12th grades (N = 761) | An online questionnaire investigating the knowledge of healthy behaviors associated with Covid with SB and PA as secondary measures |

|

|

| Guo et al. 17 | China | Cross‐sectional online survey | To determine the health behaviors (PA, SB and sleep) during Covid‐19 and compare 3 months before the pandemic | School children of 10 schools (4 urban, three sub‐urban and three exurban of Guangzhou province, China (N = 10,933) | An online questionnaire (through the professional app – Wenjuanxing and online platform WeChat) enquiring the current status of PA, sleep and screen time |

|

|

| Pelletier et al. 27 | British Columbia, Canada | Qualitative survey | To explore the experiences of children movement behaviors | 21 families with at least one parent and one child aged 7–12 years (N = 45) | Virtual meeting through zoom and interviewer prompted the parents and children about SB and PA during Pandemic. A qualitative study about barriers and facilitators. |

|

|

| Vukovic et al. 21 | Serbia | Cross‐sectional survey | To explore how the children maintained their learning, PA and screen time | Parents of children (228 boys; 222 girls; N = 450) | Online parent‐reported questionnaire |

|

Multimedia is associated with risk of depression, anxiety and nervousness (β = − 0.38) |

| Lopez‐Bueno et al. 26 | Spain | Narrative review | To investigate potential health risk behaviors among isolated pre‐school and school‐aged children during COVID 19 | School children aged 3–12 years |

|

|

|

| Abid et al. 23 | Tunisia | Cross‐sectional survey | To investigate COVID 19 restrictions on sleep quality, screen time (ST) and PA. | School‐aged children of age group (5–12 years old) (N = 52 boys and 48 girls) | Online questionnaires (Ricci and Gagnon sedentary behavior questionnaire) and digital media use scores |

|

|

| Cachón‐Zagalaz 42 | Spain | Cross‐sectional online survey | To analyze the PA and daily routine among children (0–12 years) during the lockdown and to establish the central relationships among the variables | Family and children aged 0–12 years (N = 837) | Frequency, intensity and duration of PA and screen time of the children was customized and administered through Google forms |

|

|

| Zagalaz‐Sanchez et al, 20 | Spain | Cross‐sectional study | To investigate the Spanish children's PA behavior (meeting global PA recommendations) and digital devices usage (SB) during the lockdown. |

Spanish children, aged 0–12 years (N = 837) |

|

|

|

| Alonso‐Martinez 16 | Spain | Cohort study |

|

A cohort of preschoolers aged 4 to 6 years old from three schools in Pamplona (Spain). (N = 268) |

Objective measurement: Wrist‐worn GENEActiv tri‐axial accelerometer over six consecutive days (≥600 min during awake time) |

|

|

| D'elia et al. 22 | Italy | Cluster analysis | To explore the level, quality, importance and training needs of teacher's practice comprising physical and motor activity indoors and outdoors |

Pre‐school teachers from Naples (South Italy) (N = 42) |

|

|

|

| Dunton et al. 8 | USA | Cross‐sectional survey | To investigate the effects of the COVID‐19 Pandemic on PA and SB in US children (ages 5–13 years) | Parents living in the US during the COVID‐19 pandemic (N = 211) |

|

|

|

| Siegle et al. 28 | Brazil | Cross‐sectional survey | To evaluate whether the child's socio‐demographic determinants affect the level of PA in Brazilian children during the COVID‐19 pandemic | Parents/guardians of all children under 13 years of age living in Brazil (N = 816) |

|

|

|

| Aguilar‐Farias 19 | Chile | Cross‐sectional study | To explore the socio‐demographic factors associated with changes in PA or SB in children of the Chile community | Primary caregivers of 1‐ to 5‐year‐old children living in Chile |

|

|

Across all ages, mean time spent in physical activity decreased (−0.75 h/day), recreational screen time and sleep duration increased (1.4 h/day and 0.09 h/night, respectively) and sleep quality declined (−0.75 h/day). |

| Pombo et al. 43 | Portugal | Cross‐sectional survey | To understand the nature of change in children's daily routines, including PA, SB and sleep during confinement times. | Parents of children aged younger than 13 years (N = 2159) |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular diseases; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; PA, physical activity; PC, personal computer; SB, sedentary behavior; TV, television.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Of the five databases searched, which resulted in 1039 studies by May 27, 2021, only 14 studies were found to be relevant to establish the determinants of PA or SB of children during the pandemic (Figure 1). The majority of the studies (N = 9; 64.28%) were of European origin especially Spain (N = 4; 28.57%), followed by the USA (N = 3; 21.43%), China (N = 1; 71.4%) and Canada (N = 1; 7.14%). We did not find any evidence from low‐income countries such as African countries, India, the Philippines, Pakistan or Indonesia. The respondents were heterogeneous (children, parents, and physical education teachers; N = 16,622). We found only one study 16 (7.69%) has administered objective measure of PA in their cohort while others (N = 12; 92.31%) have measured PA or SB subjectively. The majority are cross‐sectional studies (N = 13; 92.86%) conducted between March and April 2020.

Changes in the Physical Activity or Sedentary Behavior during Covid‐19

We found consistent evidence of a significant decrease in PA or a considerable increase in SB children (3–13 years of age) due to the pandemic. Children had reduced PA by 34% compared to their pre‐pandemic PA levels before the pandemic, while SB increased by 82%. 8 , 17 , 18 , 19 With support from family or school, PA increased by 38 minutes per day. 20 During this pandemic, screen time is increased by an average of 174 minutes per day while PA was reduced by 45 minutes per day. 19 , 20 It was found that 60% of screen time was associated with academic sitting. 8

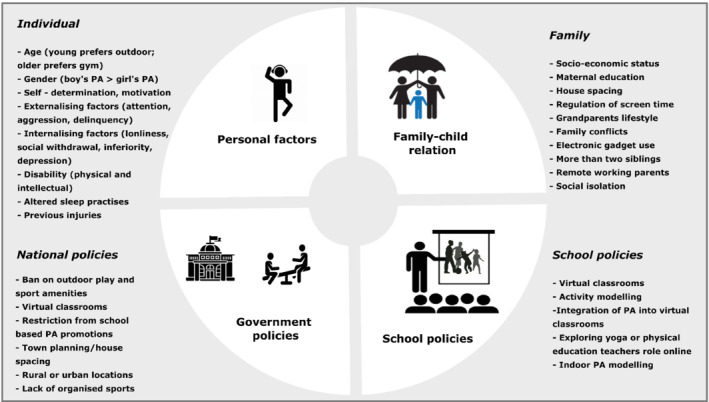

Barriers and Facilitators Identified for Effective PA or SB Interventions

We found several barriers and facilitators at personal, family, school and national levels to the effective PA promotion or SB reduction during domestic detention or restrictions during this pandemic. Various socio‐demographic and socioecological factors are summarized under four levels of PA support in children: (1) individual; (2) interpersonal or family; (3) institutional (school); (4) Environmental or national guidelines that affect the PA during COVID – 19 restrictions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factors Identified as Barriers and Facilitators for Effective PA Promotion or SB Reduction in Children during Covid‐19 Lockdown. PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behavior

Pre‐pandemic PA practices were a crucial parameter that determined the current PA or SB practices in the children. 21 Age was found to influence the type, duration, frequency, and intensity of the PA practices during the pandemic. In contrast, there are contradictions in the assertion that gender is an important determinant. Although girls were found to increase their screen time compared to boys, their PA behaviors appeared to be consistent with that of boys. 8 , 20 , 22 Psychological factors (motivation, self‐determination, fear, or aggression) were also found to influence the PA and SB in children. 16 Screen time during leisure hours such as social media use increased substantially in all age groups and in both genders, although they were seen as risk factors for reducing recreational PA in children during the pandemic. 20 , 23 Socio‐economic status, racial and ethnic minorities were also identified as the main determinants of varied PA and SB practices in children. 20 , 24 , 25 , 26 Parents as role models for PA or SB practices, apprehension about outdoor play or gathering of wards, number of children in a family, single parents, and role of child in the family were also found to be key determinants that influence PA or SB practices. 18 , 19 , 26 , 27 School closure leading to poor implementation of physical education classes online, low practices of PA during the class or recess breaks, extended hours of online engagement, lack of PA integrated classes and low PA practices by the teachers and poor school policies regarding training of the teachers in physical education curriculum during online engagement were perceived as critical determinants for poor PA practices in children. 17 , 22 Public health policies such as house location, neighborhood walkability and restricted access to outdoor play in parks were also perceived as barriers to the effective PA practice among children. 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 27

DISCUSSION

In the present review, we aimed to collate the evidence of changes in PA or SB and their determinants in children (3–13 years of age) during the COVID ‐19 pandemic. We found a significant reduction in PA and increased SB in total screen time (educational and leisure) in children. At the individual, parental, organizational (school) levels, and national (government) policies level, several barriers and facilitators to the effective PA promotion or SB reduction have been identified. Various factors that influencing children's PA or SB practices during this pandemic are discussed below:

Personal Factors and Physical Health in Children

Age : We found an inverse relationship between age and PA behaviors. With age, PA is found to reduce PA while SB increases. 16 Academic pressures, virtual classrooms, organized sports, housing planning, and social media can be perceived as the barriers for the children of the older age group (adolescents). We found a significant difference in the PA types involved according to different age groups: younger children (3‐8 years) were interested in free play activities in the home and outdoors, while the older children (9‐12 years) took part in organized sports and fitness activities.

Gender : Lower PA or increased SB were associated with gender and age differences during the ongoing pandemic. 8 The majority of the included studies showed a significant reduction in PA and increased SB in both genders during the pandemic, similar to pre‐pandemic. 8 , 28 The similarity in PA practice for both genders could be due to the fact that most activities are likely to be low intensity and due to the lack of opportunities for competitive sports events, outdoor play activities, and reduce utilization of sports facilities due to school closing and community restrictions.

Psychological factors : PA and SB in children were predominantly associated with internalizing (loneliness, social withdrawal, shyness, depression, fear, and feeling of inferiority) and externalizing behaviors (social withdrawal, loneliness, feeling of inferiority, depression, shyness, fear, and so on). 16 Loneliness and social isolation during the Covid‐19 have been strongly linked to poor mental health, which impacted PA and SB in children. 29

Family and PA Involvement

Socio‐economic status and physical health of children : PA and SB practices in children have been found to be influenced by the socio‐economic status of the family particularly family income. 18 , 20 , 26 Access to the home gym, community pools, personal trainers or exercise equipment and house spacing are primarily associated with increased levels of PA practices in children. The availability of technically advanced electronic devices, live streaming of multiple cable channels, portable television devices can all be the contributing factors driving the rise of SB practices in children. In addition, two or more children are associated with increased incidental PA. 8

Parental role on PA practices: High PA practices and low SB in children are associated with active parents who were aware of the benefits and strategies of home‐based PA practices and reduce the use of screening time. 18 , 20 , 27 Further children of remotely working mothers or single parents were found to be associated with low‐level PA practices and high level of SB during the pandemic. 16 Grant parents or caregiver's unconditional support or fear for outdoor activities was also viewed as precarious determinants for PA or SB in children during the pandemic. 17 , 27

School‐Based PA Promotional Policies

PA integrated learning : To achieve an effective PA or SB implementation, physical education should be integrated into the curriculum and combined with the virtual learning mode. 21 The teacher's expertise in promoting active classrooms (promoting recess PA breaks, standing, or exercise‐based classrooms) was also crucial for PA promotion in children. 22 Recess periods are not only found to be instrumental to achieve recommended PA but also for psychosocial benefits such as executive functions, resilience, and emotional self‐control. 30 Recently, multilevel school‐based interventions (schoolyard restructuring, active classroom, recess breaks) were found to significantly improve MVPA levels and reduce sedentary time in 6‐ to 10‐year‐old children. 31

Teachers as role models : Our review found that most (≈50%) of the school teachers did not meet the global PA recommendations, while only 23.8% met the PA recommendations. We agree with the recent survey findings that children adapt early PA practices when their teachers practice PA to a larger extent. 32

Governments/National Policies on PA Promotion in Children

Location/house spacing : Doing PA at home or in the garage, on sidewalks and streets, increased in children during confinement. 19 A moderate increase in PA was noted when space outside the home was larger than 12 m2. 19 , 28 Conversely, PA practices of children in rural areas increased marginally compared to the children of the urban area due to access to green spaces, sufficient house spacing, and little parental attention. 8 , 27 Socioeconomic factors such as low‐income and neighborhood population density are also found to influence the PA and SB in children. 33

Restriction policies : The ban on access to swimming pools, parks, or other community sports centers is significantly associated with reduced PA or longer screen time in children while in confinement. 21 , 27 The curfew timings have altered the PA practices among children. 21 Restricting shopping, and increasing door deliveries of the household chores has significantly reduced the incidental PA practices in children. Further social isolation have proposed to reduce mental health, which is independently related to physical health. 26

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

The pragmatic approach to reviewing and collating the results of the current evidence on children's physical health may be considered as the strength of this review. In addition, various confounding factors that were overlooked in the individual studies were collated to form the basis for future epidemiological and interventional studies. However, some limitations are worth noting: (1) Our aim of the present review was to provide a way for a future systematic search to analyze the effects of lockdown measures on the physical health of children. As a scoping review, we did not analyze the risk of bias in the epidemiological studies included. 34 Due to potential heterogeneity and publication bias, stakeholders should be cautious in interpreting our findings before establishing the guidelines on physical health for children. (2) The majority of studies used subjective measures of PA and SB, which may have induced a source of recall bias in our review findings 35 ; (3) The majority of studies are of Spanish origin. 16 , 20 Considerable evidence in languages other than English were excluded. In addition, we found evidence only from developed countries while the low‐middle income countries stand on children physical health is largely unknown. We recommend that future studies consider the above factors and intervene with appropriate behavior change techniques and intervention mapping to promote physical health in children. 36

To conclude, the preventive measures recommended to contain COVID‐19 have resulted in significant reductions in PA and an increase in SB in children aged 3 to 13 years. The barriers identified in the review can help the government/policymakers to develop effective programmatic and policy strategies to reduce sedentary behavior/screen time and to optimally improve PA in children during the pandemic state.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

Context‐specific environments such as schools are ideal for PA promotion and SB reduction, as children spend 2nd/3rd of their awake time in schools. 37 Governments have put schools at the forefront of providing PA solutions to mitigate the chronic disease risk as the children can be easily reached through schools. Four dimensions in school‐based PA that form an ideal part of improving PA and reducing SB are (1) promoting PA during physical education classes; (2) recess time PA breaks; (3) active classrooms with integrated PA; (4) commute time. 31 Conversely, schools in low‐middle income countries have been closed to contain the viral spread among children and the significant portion of PA has been reduced. The virtual classrooms, inadequate training of teachers to implement virtual PA engagement classes and promotion, extended hours of craft classes online, and lack of commute to school and recess PA breaks have substantially increased the sitting time. Poor PA practices and long sitting time in children are linked to poor motor skill development, low energy expenditure leading to obesity and other cardio metabolic disease risk and cognitive dysfunctions that leads to poor academic performances. 38 With our review findings, we recommend that schools should advocate appropriate strategies to ensure optimum PA practices or SB reduction in children as follows:

“Train the trainers”: Training teachers to implement the virtual mode of PA (dance, yoga, fundamental movement skills) and to integrate the PA and SB practices to their classes (active classroom: standing classroom, walking discussions). 39 Training the trainers may lead to the greater uptake of the behavior change techniques during virtual class rooms. 40

Supporting extended hours of home‐based physical education with minimal resources and monitoring for skill and safety.

Virtual parental education programs regarding PA and SB practices ensuring that the children meet recommended PA guidelines and breaking sedentary time during their sibling's online learning hours, being active role model for their siblings, PA and SB practices and leisure time PA practices.

Incentivizing the virtual fitness, game challenges, and supporting group tasks among student peers.

Encouraging outdoor play with adequate precautionary measures: masking compliance, social distancing, and hand hygiene post play. Several other measures such as sanitizing sports equipment's/surfaces and avoiding contact sports should be advocated. 41

“Reach the non‐reachable”: teaching inclusive PA online for children with special needs and differently abled kids. Adapted physical activity was found to improve child's engagement and social wellbeing.

Encouraging walk breaks between the classes and engage in fun‐filled activities.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization BC conceived the idea.

Data curation MR and BC developed the protocol and search methodology. MR conducted the search strategy.

Formal analysis Both the authors (MR and BC) have analysed the retrieved studies and performed the scoping review.

Validation Both the authors (MR and BC) verified the included studies and collated the results.

Visualisation The co‐author (BC) visualised the results.

Writing – Original Draft MR wrote the original draft.

Writing – Review & Editing BC reviewed and provided critical inputs on the final draft.

The authors wish to thank Dr Fiddy Davis, Head of the department, Department of Exercise and Sports Sciences, Manipal College of Health Professions, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka, India for his support towards research.

Contributor Information

Mansoor Rahman A, Email: mansoorrahman_jsscpt@jssonline.org.

Baskaran Chandrasekaran, Email: baskaran.c@manipal.edu.

Data availability statement

The data regarding data extraction, study inclusion and exclusion based on eligibility criteria as specified in the manuscript is available with the primary author. On request, the data will be provided to the readers of Journal of School Health.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . COVID‐19 weekly operational update. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly‐operational‐update‐on‐covid‐19‐24‐may‐2021, accessed on 24 May 2021.

- 2. Jakobsson J, Malm C, Furberg M, Ekelund U, Svensson M. Physical activity during the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic: prevention of a decline in metabolic and immunological functions. Front Sports Act Living. 2020;2:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bull FC, Al‐Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451‐1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tarp J, Child A, White T, et al. Physical activity intensity, bout‐duration, and cardiometabolic risk markers in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(9):1639‐1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook CJ, Howard SJ, Scerif G, et al. Associations of physical activity and gross motor skills with executive function in preschool children from low‐income south African settings. Dev Sci. 2019;22(5):e12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verswijveren SJJM, Lamb KE, Bell LA, Timperio A, Salmon J, Ridgers ND. Associations between activity patterns and cardio‐metabolic risk factors in children and adolescents: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Cauwenberghe E, Jones RA, Hinkley T, Crawford D, Okely AD. Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in preschool children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dunton GF, Do B, Wang SD. Early effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gråstén A. School‐based physical activity interventions for children and youth: keys for success. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6(3):290‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagata JM, Abdel Magid HS, Pettee GK. Screen time for children and adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(9):1582‐1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chandrasekaran B, Pesola AJ, Rao CR, Arumugam A. Does breaking up prolonged sitting improve cognitive functions in sedentary adults? A mapping review and hypothesis formulation on the potential physiological mechanisms. Review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021;22(1):274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biddle SJH, Atkin AJ, Cavill N, Foster C. Correlates of physical activity in youth: a review of quantitative systematic reviews. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;4(1):25‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardner B, Smith L, Lorencatto F, Hamer M, Biddle SJ. How to reduce sitting time? A review of behaviour change strategies used in sedentary behaviour reduction interventions among adults. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(1):89‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernandez ME, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Intervention mapping: theory‐ and evidence‐based health promotion program planning: perspective and examples. Front Public Health. 2019;7:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alonso‐Martinez AM, Ramirez‐Velez R, Garcia‐Alonso Y, Izquierdo M, Garcia‐Hermoso A. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep and self‐regulation in Spanish preschoolers during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guo YF, Liao MQ, Cai WL, et al. Physical activity, screen exposure and sleep among students during the pandemic of COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell K, Weingart R, Ashta J, Cronin T, Gazmararian J. COVID‐19 knowledge and behavior change among high school students in semi‐rural Georgia. J Sch Health. 2021;91(7):526‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aguilar‐Farias N, Toledo‐Vargas M, Miranda‐Marquez S, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of changes in physical activity, screen time, and sleep among toddlers and preschoolers in Chile during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zagalaz‐Sánchez ML, Cachón‐Zagalaz J, Arufe‐Giráldez V, Sanmiguel‐Rodríguez A, González‐Valero G. Influence of the characteristics of the house and place of residence in the daily educational activities of children during the period of COVID‐19′ confinement. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):e06392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vukovic J, Matic RM, Milovanovic IM, Maksimovic N, Krivokapic D, Pisot S. Children's daily routine response to COVID‐19 emergency measures in Serbia. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:656813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D'elia F, D'isanto T. Body, movement, and outdoor education in pre‐school during covid‐19: perceptions of future teachers during university training. J Phys Educ Sport. 2021;21:580‐584. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abid R, Ammar A, Maaloul R, Souissi N, Hammouda O. Effect of COVID‐19‐related home confinement on sleep quality, screen time and physical activity in Tunisian boys and girls: a survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López‐Aymes G, Valadez MLD, Rodríguez‐Naveiras E, Castellanos‐Simons D, Aguirre T, Borges Á. A mixed methods research study of parental perception of physical activity and quality of life of children under home lock down in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:649481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopez‐Bueno R, Lopez‐Sanchez GF, Casajus JA, et al. Health‐related behaviors among school‐aged children and adolescents during the Spanish Covid‐19 confinement. Front Pediatr. 2020;8(573):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lopez‐Bueno R, Lopez‐Sanchez GF, Casajus JA, Calatayud J, Tully MA, Smith L. Potential health‐related behaviors for pre‐school and school‐aged children during COVID‐19 lockdown: a narrative review. Prev Med. 2021;14:3106349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pelletier CA, Cornish K, Sanders C. Children's independent mobility and physical activity during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a qualitative study with families. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Siegle CBH, Pombo A, Luz C, Rodrigues LP, Cordovil R, Sá C. Influences of family and household characteristics on children's level of physical activity during social distancing due to Covid‐19 in Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2020;39:e2020297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loades M, Chatburn E, Higson‐Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID‐19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218‐1239.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Massey WV, Thalken J, Szarabajko A, Neilson L, Geldhof J. Recess Quality and Social and Behavioral Health in Elementary School Students. Journal of School Health. 2021;91(9):730‐740. 10.1111/josh.13065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bernal C, Lhuisset L, Bru N, Fabre N, Bois J. Effects of an intervention to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary time in disadvantaged children: randomized trial. J Sch Health. 2021;91(6):454‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheung P. Teachers as role models for physical activity: are preschool children more active when their teachers are active? Eur Phy Educ Rev. 2020;26(1):101‐110. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morin P, Lebel A, Robitaille É, Bisset S. Socioeconomic factors influence physical activity and sport in Quebec schools. J Sch Health. 2016;86(11):841‐851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prince S, Adamo K, Hamel M, Hardt J, Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self‐report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kok G, Gottlieb N, Peters G, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):297‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hegarty LM, Mair JL, Kirby K, Murtagh E, Murphy MH. School‐based interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in children: a systematic review. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3(3):520‐541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):1143‐1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carrillo C, Flores M. COVID‐19 and teacher education: a literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur J Teacher Educ. 2020;43(4):466‐487. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abi Nader P, Hilberg E, Schuna JM Jr, John DH, Gunter KB. Association of teacher‐level factors with implementation of classroom‐based physical activity breaks. J Sch Health. 2019;89(6):435‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen PJ, Mao LJ, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li FZ. Returning Chinese school‐aged children and adolescents to physical activity in the wake of COVID‐19: actions and precautions. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(4):322‐324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cachon‐Zagalaz J, Zagalaz‐Sanchez ML, Arufe‐Giraldez V, Sanmiguel‐Rodriguez A, Gabriel V. Physical activity and daily routine among children aged 0–12 during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pombo A, Luz C, Rodrigues LP, Ferreira C, Cordovil R. Correlates of children's physical activity during the COVID‐19 confinement in Portugal. Public Health. 2020;189:14‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data regarding data extraction, study inclusion and exclusion based on eligibility criteria as specified in the manuscript is available with the primary author. On request, the data will be provided to the readers of Journal of School Health.