Abstract

Pyramidal neurons exhibit a complex dendritic tree that is decorated by a huge number of spine synapses receiving excitatory input. Synaptic signals not only act locally but are also conveyed to the nucleus of the postsynaptic neuron to regulate gene expression. This raises the question of how the spatio-temporal integration of synaptic inputs is accomplished at the genomic level and which molecular mechanisms are involved. Protein transport from synapse to nucleus has been shown in several studies and has the potential to encode synaptic signals at the site of origin and decode them in the nucleus. In this review, we summarize the knowledge about the properties of the synapto-nuclear messenger protein Jacob with special emphasis on a putative role in hippocampal neuronal plasticity. We will elaborate on the interactome of Jacob, the signals that control synapto-nuclear trafficking, the mechanisms of transport, and the potential nuclear function. In addition, we will address the organization of the Jacob/NSMF gene, its origin and we will summarize the evidence for the existence of splice isoforms and their expression pattern.

Keywords: Jacob/NSMF, CREB, NMDAR, nuclear localization signal (NLS), importin-α1, synaptic plasticity

Introduction

The complex morphology of neuronal cells poses a major challenge to integrate and link synaptic signals arising on distant dendritic branches to nuclear gene expression. This is a rather complex process and may require different modes of regulation. Several excitation-transcription coupling pathways are triggered downstream of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Activation of Ca2+ signaling in the neuronal soma includes modulation of calcium release from intracellular calcium stores, backpropagating action potentials, somatic propagation of dendritic Ca2+ spikes that are independent of action potentials (Cohen and Greenberg, 2008; Hardingham and Bading, 2010; West and Greenberg, 2011; Bading, 2013; Morris, 2013; Volianskis et al., 2015; Wild et al., 2019). Thus, not only nuclear Ca2+ -waves elicited by NMDAR and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are instrumental in the control of gene expression but also soma-to-nucleus signaling is regulated by Ca2+ and might, for instance, control the nuclear import of transcription factors (Wild et al., 2019). However, it is questionable that calcium signals alone can elicit a specific nuclear response that precisely encodes signals coming from distinct receptors located on different dendritic sites and activated by diverse stimuli.

Long-distance transport of macromolecular protein signaling complexes can potentially provide a more precise means of encoding and transducing different types of synaptic activation to the nucleus. The type of information might include for instance the localization and a number of activated NMDAR and published evidence suggests that synapto-nuclear protein messenger might convey this type of information to the nucleus where it is translated in distinct long-lasting changes in gene expression (Dieterich et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2008; Fainzilber et al., 2011; Ch’ng et al., 2012; Karpova et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2013; Dinamarca et al., 2016; Kravchick et al., 2016).

The prevalent model of activity-induced protein transport from synapses to the nucleus implies the binding of a nuclear localization signal (NLS) in synapto-nuclear protein messengers with one of the importin-α family members in response to synaptic activation. This is followed by binding to importin-β and association with a dynein motor that eventually mediates the transport of the protein complex along microtubule toward the nucleus (Cingolani et al., 1999; Fainzilber et al., 2011; Ch’ng and Martin, 2011; Kaushik et al., 2014; Lever et al., 2015; Panayotis et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2020).

Jacob Signalosome and Its Function in the Regulation of Gene Expression

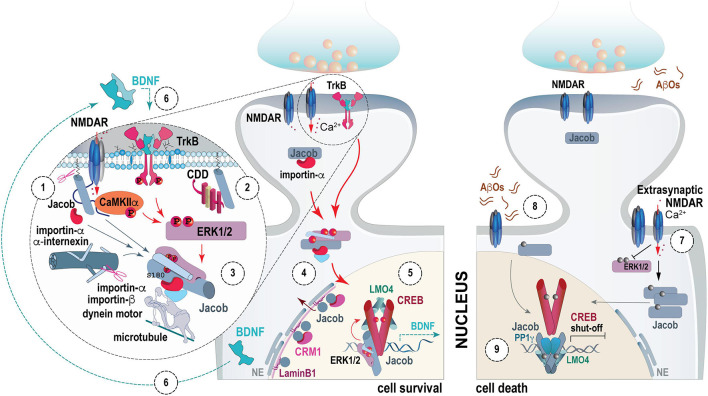

Jacob, the protein encoded by the NSMF gene, is a synapto-nuclear messenger that encodes and transduces NMDAR signals to the nucleus (Karpova et al., 2013). Jacob assembles a signalosome likely in close vicinity to NMDAR and following long-distance transport docks this signalosome to the transcription factor cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB, Figure 1; Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013; Spilker et al., 2016b; Grochowska et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1.

Molecular mechanisms underlying synapse-to-nucleus trafficking of Jacob and its nuclear function. N-terminal myristoylation is a prerequisite for the extranuclear localization of Jacob. In synapses, Jacob associates with the GluN2B-containing NMDA receptor complex as well as CaMKII-α (1). The synaptic localization is regulated by the neuronal Ca2+ sensor protein Caldendrin (2) that competes with importins for Jacob binding. NMDAR activation leads to calpain-mediated cleavage of the myristoylated part of the protein and releases Jacob from the plasma membrane. Concomitantly, synaptic GluN2B-containing NMDAR activity leads to CaMKII-α dependent activation of ERK1/2, subsequent phosphorylation of Jacob at S180 and formation of a stable trimeric complex between phosphorylated Jacob, active ERK1/2 and the proteolytically cleaved fragment of the neuronal filament α-internexin (3) which protects pJacob and pERK1/2 against phosphatase activity during retrograde transport to the nucleus but likely also in the nucleus. Long-distance transport of the Jacob signalosome involves its association with importin-α, importin-β, and, subsequently the molecular motor dynein that moves along microtubules in a retrograde direction. GluN2B-containing NMDA receptor activity mediates the association of Jacob with the inner nuclear membrane where it transiently binds to LaminB1 (4). The association with the canonical CRM1-RanGTP-dependent export complex defines its nuclear residing time. In the nucleus, the Jacob signalosome associates with the CREB complex and results in its sustained activation by docking the active ERK1/2 in its close vicinity (5). This, in turn, promotes CREB-dependent gene expression of plasticity-related genes like Bdnf. In early development, BDNF induces the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated Jacob in an NMDAR-dependent manner, which results in increased phosphorylation of CREB and enhanced CREB-dependent Bdnf gene expression in a positive feedback loop (6). Activation of extrasynaptic NMDARs by NMDA (7) or AβOs (8) does not lead to phosphorylation of ERK1/2 or Jacob. Nevertheless, the non-phosphorylated protein translocates to the nucleus (9) piggyback with the CREB phosphatase, PP1. In addition, it displaces CREB from the transcriptional co-activator LMO4 leading to CREB shut-off. CDD, Caldendrin; NE, nuclear envelope; red circle, phosphorylation; gray circle, unphosphorylated site; TrkB, Tropomyosin receptor kinase B; NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; LMO4, LIM domain only 4; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CRM1, chromosomal maintenance 1; ERK1/2, Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2; PP1, protein phosphatase 1. Scissors indicate cleavage.

NMDARs have been implicated in synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, cell survival signaling, but also in neurodegeneration and excitotoxicity (Paoletti et al., 2013; Pagano et al., 2021). A prevailing hypothesis in the field suggests that the opposing functions of NMDARs attribute to their subcellular localization and subunit composition. Signaling downstream of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDARs is tightly coupled with the transcriptional activity of CREB where activation of synaptic NMDARs promotes its sustained phosphorylation at a crucial serine residue at position 133 and subsequent expression of plasticity-related genes (Hardingham and Bading, 2010). Therefore, synaptic NMDARs are crucial for plasticity processes like the expression of long-term potentiation (LTP), memory encoding and consolidation (Shimizu et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2004; Jordan et al., 2007; Dieterich et al., 2008; Jeffrey et al., 2009; Jordan and Kreutz, 2009; Hardingham and Bading, 2010; Kaufman et al., 2012; Morris, 2013; Papouin and Oliet, 2014; Dinamarca et al., 2016; Bading, 2017). Conversely, activation of extrasynaptic GluN2B-containing NMDARs leads to sustained dephosphorylation of CREB, also known as CREB shut-off, rendering CREB transcriptionally inactive (Hardingham et al., 2002; Hardingham and Bading, 2010; Rönicke et al., 2011; Bading, 2013).

Loss of CREB-dependent pro-survival gene expression after extrasynaptic NMDAR activation seems to precede cell death and neurodegeneration in diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Huntington’s disease (HD) (Shankar et al., 2007; Milnerwood et al., 2010; Malinow, 2012; Kessels et al., 2013; Papouin and Oliet, 2014; Parsons and Raymond, 2014; Wild et al., 2015; Carvajal et al., 2016; Bading, 2017; Grochowska et al., 2017; Marcello et al., 2018; Parra-Damas and Saura, 2019). Especially in AD, dysregulation of CREB-dependent gene expression apparently plays a role in the onset of the disease and early synaptic dysfunction (Saura and Cardinaux, 2017).

The synaptic localization of Jacob is mediated in part by its association with the plasma membrane via a myristoyl group attached to its N-terminal glycine residue (Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013). In addition, Jacob associates with calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-α (CamKII-α) and with the C-terminal tail of the GluN2B subunit of NMDAR (Figure 1.1; Dieterich et al., 2008; Dinamarca et al., 2016; Melgarejo da Rosa et al., 2016). In spine synapses, the neuronal Ca2+ sensor protein Caldendrin binds to a central IQ-like motif of Jacob and thereby masks a bipartite NLS involved in importin-α binding (Figure 1.2; Dieterich et al., 2008). Interestingly, Caldendrin is like Jacob particularly prominent in larger mushroom-like dendritic spines that are tightly sealed by the spine neck and show highly compartmentalized Ca2+-responses (Seidenbecher et al., 1998; Dieterich et al., 2008; Mikhaylova et al., 2018). Binding of Jacob to Caldendrin presumably keeps the protein in spines until all steps of signalosome formation are accomplished. Hence, the influx of Ca2+ through NMDARs is crucial for the release of Jacob from synaptic sites since it activates the protease calpain, which in turn cleaves the myristoylated N-terminal part releasing the protein from the plasma membrane (Figure 1.1; Kindler et al., 2009; Karpova et al., 2013).

Ca2+-influx through GluN2B-containing synaptic NMDARs leads to the subsequent activation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated protein Kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) via Ca2+/CaMKII-α (El Gaamouch et al., 2012). This results in phosphorylation of Jacob at a crucial serine residue at position 180 (S180/Figure 1.3; Karpova et al., 2013; Melgarejo da Rosa et al., 2016). Concomitantly, Jacob phosphorylated at S180 and active ERK1/2 assemble a trimeric complex with calpain cleaved fragments of the intermediate neuronal filament α-internexin. The binding of α-internexin further stabilizes the Jacob/ERK1/2 complex and protects it from the cytosolic phosphatase-rich environment of neurons en route to the nucleus (Karpova et al., 2013).

The adaptor protein importin-α1/Rich1 (encoded by KPNA2 gene), which links cargo to importin-β1, directly interacts with the NLS of Jacob and this interaction is essential for transport (Figure 1.3; Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013). Likely, that this complex is already formed at synapses since both, importin-α1 and importin-β1 are present at spines and distal dendrites and have been shown to translocate to the nucleus in response to synaptic activity (Thompson et al., 2004). There are at least seven importin-α family members expressed in the mammalian brain (Kelley et al., 2010), but whether they compete for binding to Jacob’s NLS is currently unclear. Potentially, multiple combinations of importin-α/importin-β complexes exist and might represent the importin code of synapto-nuclear protein messengers that depicts the grand cargo specificity (Lever et al., 2015). Finally, the Jacob signalosome associates with the molecular motor cytoplasmic dynein that is instrumental for trafficking of the protein complex along microtubules toward the nucleus (Karpova et al., 2013).

Following NMDAR-dependent nuclear import, Jacob transiently associates with the inner nuclear membrane (Figure 1.4) by direct interaction with the nuclear lamina protein LaminB1 and the nuclear export adaptor chromosomal maintenance 1 (CRM1; Samer et al., 2021). At present, it is unclear whether the nuclear lamina merely provides a docking site for an intermediate step relevant for either subsequent redistribution of Jacob to nuclear target sites or its nuclear export (Samer et al., 2021).

A prominent nuclear target of Jacob is the transcription factor CREB (Figure 1.5). Of note, the direct interaction of Jacob with CREB does not depend on the phosphorylation of S180. In response to synaptic NMDAR activation, Jacob phosphorylated at S180 accumulates in the nucleus (Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013; Spilker et al., 2016b; Grochowska et al., 2017) where it then binds CREB (Karpova et al., 2013; Grochowska et al., 2020).

Association with Jacob promotes CREB phosphorylation at S133 in an ERK-dependent manner and thereby links synaptic NMDAR activity to CREB-dependent gene expression related to synaptic plasticity (Figure 1.6; Karpova et al., 2013; Spilker et al., 2016b).

Interestingly, Jacob is imported to the nucleus in rat hippocampal slices and neuronal cultures only after induction of NMDAR-dependent LTP but not Ltd. (Behnisch et al., 2011; Yuanxiang et al., 2014; Melgarejo da Rosa et al., 2016). Of note, it accumulates in the nucleus already within 30 min after LTP induction, a time window critical of activity-induced gene expression required for long-lasting LTP expression (Frey et al., 1996; Behnisch et al., 2011). Accordingly, Jacob/NSMF knockout mice display impaired expression of Schaffer collateral LTP (Spilker et al., 2016b), emphasizing a potential role of the messenger protein in transmitting LTP-related signals from synapse to nucleus.

Synaptic NMDAR signals are key for Jacob nuclear import in mature neurons. However, BDNF, whose expression is regulated via the NMDAR-Jacob-CREB pathway, can also promote the accumulation of S180 phosphorylated Jacob in the nucleus in neuronal development as part of a positive feedback loop that drives BDNF expression in a CREB-dependent manner (Figure 1.6; Spilker et al., 2016a,b). BDNF-dependent translocation of Jacob to the nucleus appears to play a critical role in hippocampal development. Accordingly, Jacob/NSMF knockout mice display hippocampal dysplasia that is characterized by reduced complexity of the dendritic tree of pyramidal neurons, a reduced number of synaptic contacts, an altered catechol- and monoaminergic innervation, as well as reduced BDNF expression and impaired nuclear ERK1/2 and CREB signaling (Spilker et al., 2016a,b). Structural alterations in the hippocampus correlate with functional deficits related to learning and memory. Particularly, Jacob/NSMF knockout mice show impaired contextual fear conditioning and object recognition memory, behavioral tasks that are sensitive to hippocampal dysfunction (Spilker et al., 2016a,b).

Activation of extrasynaptic NMDARs leads to the formation and translocation of a different Jacob transport complex (Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013; Grochowska et al., 2020). Several lines of evidence indicate that extrasynaptic NMDAR activity evoked by the block of synaptic NMDARs and subsequent treatment with NMDA induces dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Jacob (Figure 1.7; Ivanov et al., 2006;Rönicke et al., 2011; Karpova et al., 2013; Gomes et al., 2014; Grochowska et al., 2017; Grochowska et al., 2020) and triggers CREB shut-off resulting in synaptic dysfunction, synapse loss and subsequent cell death (Hardingham and Bading, 2010; Yan et al., 2020). Soluble amyloid-β oligomers (AβOs) are causative agents underlying the onset and progression of AD (Selkoe and Hardy, 2016; Cline et al., 2018). It was shown that different AβOs species, Aβ1-42 and Aβ25-35, act on extrasynaptic NMDARs and drive non-phosphorylated Jacob in the nucleus which triggers CREB shut-off (Figure 1.8; Rönicke et al., 2011; Gomes et al., 2014; Grochowska et al., 2017, 2020). Jacob seems to play a role in extrasynaptic NMDAR signaling linked to neurodegenerative disorders and interrupted CREB-dependent gene expression at the early stage of AD pathology (Rönicke et al., 2011; Gomes et al., 2014; Grochowska et al., 2017, 2020). Along these lines, Jacob protein knockdown abolished AβOs-induced CREB shut-off and, concurrently, ameliorated neuronal loss in the CA1 area of the hippocampus in a double transgenic AD mouse line lacking the NSMF gene (Grochowska et al., 2020).

In mature neurons, non-phosphorylated nuclear Jacob preferentially binds to LIM domain Only 4 (LMO4), a CREB coactivator, replaces LMO4 from the transcription factor complex and impairs its transcriptional activity (Figure 1.9; Grochowska et al., 2020). Furthermore, nuclear non-phosphorylated Jacob docks the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) to CREB sites further promoting its transcriptional inactivation (Hardingham and Bading, 2010; Grochowska et al., 2017, 2020). Interestingly, both CREB shut-off and nuclear import of non-phosphorylated Jacob cannot be induced in young neuronal cultures, less than 9 days in vitro (DIV), which indicates that this type of signaling requires a certain level of network maturation and substantial expression of GluN2B-containing NMDAR at extrasynaptic sites (Sheng et al., 1994; Sala et al., 2000; Hardingham et al., 2002; Behnisch et al., 2011).

Although extensively studied in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, the extrasynaptic NMDAR pathway has also been shown to play an important role in classical synaptic memory mechanisms (Henneberger et al., 2020; Herde et al., 2020) and behavior (Homiack et al., 2017). Using a synthetic predator odor 2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline (TMT) exposure protocol as a model of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in rats, Homiack et al. (2017) have shown that TMT exposure reduced phosphorylation of CREB in male, but not female rats. Moreover, reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation together with an increase in nuclear accumulation of Jacob was also found in the hippocampus of male rats, strong evidence of the activation of the CREB shut-off pathway. The differential signaling cascade activation between sexes warrants further investigation, given that TMT exposure produces the same outcome in both sexes at the behavioral level.

Cell-Type Specific Expression Patterns, NSMF Gene Structure and Jacob Splice Isoforms

Studies on the function of Jacob as synapto-nuclear protein messenger have been mainly done in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus and cortex (Dieterich et al., 2008; Kindler et al., 2009; Behnisch et al., 2011; Karpova et al., 2013; Mikhaylova et al., 2014). However, Jacob is expressed in neurons of various brain regions (Mikhaylova et al., 2014) and it would be interesting to learn whether it has a similar function in other neuronal cell types. In pyramidal neurons the protein is present in distal dendrites and axons where it localizes to pre- and postsynaptic sites with a clear enrichment at the postsynaptic density (PSD) as confirmed by fluorescence and electron microscopy (EM) as well as by subcellular fractionation experiments (Dieterich et al., 2008; Mikhaylova et al., 2014). Jacob is prominently present in nuclei of pyramidal neurons where it associates with distinct nuclear loci including the inner nuclear membrane (Samer et al., 2021). Although Jacob is expressed in Parvalbumin-, Calbindin-, and Calretinin-positive interneurons of the hippocampus as well as in medium spiny neurons (MSN) of the striatum, principal differences in the expression pattern of Jacob between excitatory and inhibitory neurons concern the synaptic localization of the protein, although inhibitory neurons show a somato-dendritic distribution of Jacob. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) imaging revealed that the protein is absent at inhibitory shaft synapses and expressed at very low levels only in a subset of cortico-striatal synapses of medium spiny neurons (Mikhaylova et al., 2014; Bär, 2015). Interestingly, however, the nuclear localization of Jacob is very similar between inhibitory and excitatory neurons (Dieterich et al., 2008; Behnisch et al., 2011; Mikhaylova et al., 2014).

Jacob/NSMF expression appears to be developmentally regulated with the highest mRNA levels during synaptogenesis, between the second and the third postnatal week (Dieterich et al., 2008; Kindler et al., 2009; Bär, 2015). This period also correlates with an increase in Jacob protein expression. The Jacob/NSMF mRNA shows a prominent dendritic localization in the hippocampus (Kindler et al., 2009). Like other proteins that might be locally translated in dendrites, the Jacob/NSMF mRNA harbors a dendritic targeting element (DTE) that is part of the 3‘UTR region of the transcript (Kindler et al., 2009). Further evidence for local translation of Jacob’s dendritic mRNA in cortical neurons comes from a study employing SynapTRAP, a synaptoneurosomal fractionation followed by translating ribosome affinity purification (Ouwenga et al., 2017). Like all dendritic mRNAs isolated in this study, the Jacob mRNA had a disproportionately longer length and was enriched for Fragile-X mental retardation protein (FMRP) binding. Interestingly, Jacob is an FMRP target (Kindler et al., 2009) and multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) revealed that in comparison to the cellular distribution of ∼4200 RNA species in hippocampal primary cultures Jacob/NSMF mRNA expression in distal dendrites belongs to the top 10% of transcripts showing the highest dendrite-to-soma transcript ratio (Wang et al., 2020). Local translation likely replenishes the synaptic protein pool following synapse-to-nucleus transport. Unfortunately, it is at present unclear whether only certain transcripts containing the NLS and the synaptic targeting element are preferentially translated in dendrites (see also below).

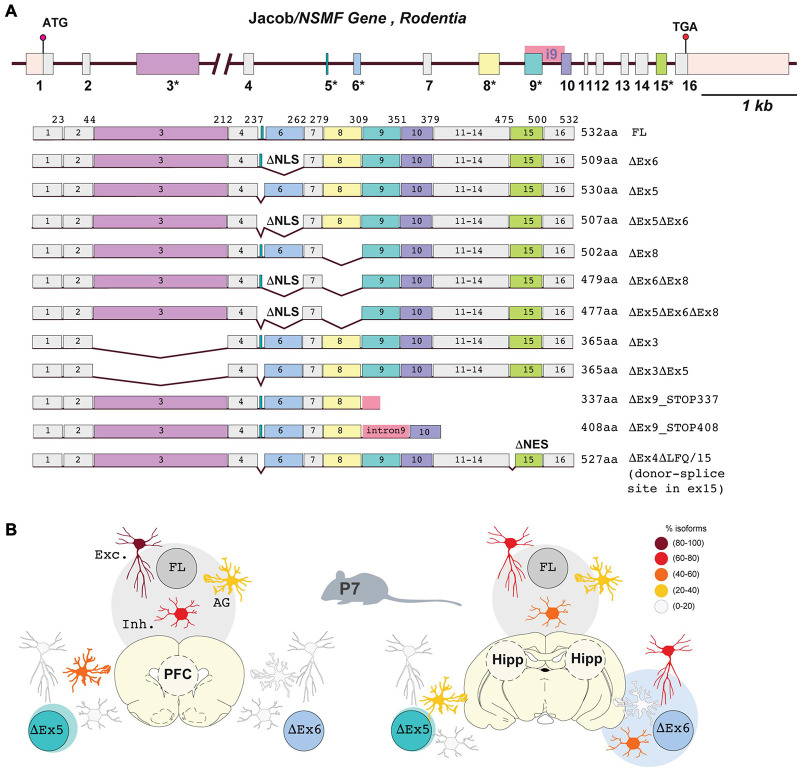

The Jacob/NSMF gene structure is rather complex with 16 exons (Figure 2A) and high sequence conservation between mammalian species. It has been shown that at least 5 out of 16 exons of the Jacob/NSMF gene can be alternatively spliced (Figure 2A; Miura et al., 2004; Dieterich et al., 2008; Kindler et al., 2009; Miura et al., 2013; Quaynor et al., 2014;Joglekar et al., 2021). The existence of many Jacob/NSMF isoforms are predicted, but not all of them are experimentally confirmed and not much information is available about brain region- and cell type-specific expression of splice variants and regulation of expression in development. The most recent version of the database from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, 09.2021) indicates 13 isoforms for mouse Jacob/NSMF (M. musculus, Gene ID: 56876) out of which 8 are validated. For the human Jacob/NSMF gene (H. sapiens, Gene ID: 26012) 5 out of 10 transcripts predicted by automated computational analysis are confirmed.

FIGURE 2.

Jacob/NSMF gene in rodents comprises 16 exons from which at least 5 are alternatively spliced. (A) Schematic representation of Jacob/NSMF gene structure (modified from Spilker et al., 2016a) and experimentally confirmed alternatively spliced mRNA variants resulting in various protein isoforms. Numbers with an asterisk represents alternatively spliced exons. Exons that are not spliced are indicated in gray. Isoform name and its length in amino acids (aa) are indicated in the right panel. (B) Schematic representation of the cell type-specific relative expression pattern of Jacob/NSMF splice variants based on single-cell isoform RNA sequencing and genePlot analysis. Indicated are excitatory neurons (Exc.), inhibitory neurons (Inh.) and astrocytic glia (AG). Color code from white-to-dark red indicates relative amounts of mRNA transcripts in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus (Hipp) in early development (P7 mouse brain). Shaded circles indicate the relative abundance of a particular isoform vs. others within the brain region.

Experimental studies on Jacob/NSMF mRNA expression have shown that several Jacob/NSMF transcripts are present in the mouse, rat, and human brain (Dieterich et al., 2008; Kindler et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2011). Single-cell isoform RNA sequencing in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus of the mouse brain at postnatal day 7 suggests that Jacob/NSMF is widely expressed in inhibitory and excitatory neurons in both brain regions (Figure 2B; Joglekar et al., 2021). Interestingly, the expression of an isoform lacking exon 6 appeared to be restricted to hippocampal neurons. This 69 nucleotide (nt)-long exon encodes a nuclear localization signal and part of the IQ- domain that forms the interface for Caldendrin binding. Therefore, alternative splicing of this specific exon may affect the synapto-nuclear distribution of Jacob and its nuclear function. Altogether, the expression of the full length (FL) isoform in the PFC is relatively higher in comparison to the hippocampus due to the absence of other isoforms. This poses the PFC as a well-suited region for the study of the synapto-nuclear function of the protein. A Jacob transcript lacking the 6 nt-long exon 5 was detected only in glial cells of the PFC in P7 mouse brains (Figure 2B; Joglekar et al., 2021), which is at variance with the lack of Jacob protein expression in astro- and microglia in adult rat brain (Mikhaylova et al., 2014).

Evolutionary Conservation of the Coding Sequence of the Jacob/NSMF Gene

Most studies on the synapto-nuclear messenger function of Jacob were performed with mammalian species (Dieterich et al., 2008; Kindler et al., 2009; Behnisch et al., 2011; Karpova et al., 2013; Melgarejo da Rosa et al., 2016; Spilker et al., 2016b; Grochowska et al., 2017). However, the NSMF gene has also been found in zebrafish [called nasal embryonic LHRH factor (NELF); Kramer and Wray, 2000; Palevitch et al., 2009]. A database search shows that the NSMF gene is present in vertebrates comprising all groups of the taxon euteleostomi, namely Tetrapoda and Osteichthyes (bony fish). The recently updated NCBI database (09.2021) contains entries for NSMF genes in 280 species. Examples include mammals (e.g., R. norvegicus, M. musculus, H. sapiens, P. troglodytes) but also birds (e.g., G. gallus), reptiles (e.g., Chr. picta), amphibians (e.g., X. tropicalis), and fish (e.g., D. rerio) (Table 1). An extended Ensembl (release 104) genome database project (Howe et al., 2020) search identified the NSMF gene sequence in a scaffold of the sea lamprey (P. marinus). Although the total gene size varies from 8.5 kb in mouse to approximately 80 kb in zebrafish the exon organization is highly conserved with an exception for the lowest vertebrate P. marinus where exon boundaries are shifted, and the number of Jacob coding regions is 17. It is striking that the homology in the Jacob amino acid sequence between R. norvegicus, G. gallus, D. rerio (NSMF a gene) and P. marinus is very high in its C-terminus, especially within the regions encoded by exons 10-16 where most species show sequence identity. The differences in amino acid sequence between different species concern largely parts of the protein encoded by exon 3 (which is alternatively spliced), as well as exons 8 and 9. Altogether, these findings suggest that Jacob is expressed throughout all vertebrates (Table 1) with the highest conservation within its C-terminus. Vice versa, no invertebrate ortholog of Jacob was found using diverse tools [i.e., NCBI Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) search1]. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) of different exons of diverse species, Ensembl genome database project (release 104; Howe et al., 2020), NCBI HomoloGene).

TABLE 1.

Accession numbers of Jacob protein and Jacob/NSMF gene sequences reviewed for conservation.

| Species | Common name | Genomic, cDNA or mRNA sequence | Protein sequence |

| H. sapiens | Human | NM_001130969.3 GeneID 26012 ENST00000371475 | NP_001124441.1 |

| R. norvegicus | Common rat | NM_057190.2 GeneID 117536 ENSRNOT00000061303 | NP_476538.2 Uniprot Q9EPI6 |

| M. musculus | House mouse | NM_001039386.1 GeneID 56876 ENSMUST00000100334 | NP_001034475.1 Uniprot Q99NF2 |

| G. gallus | Chicken | GeneID 417260 ENSGALG00000008681 XM_015279659.3 | XP_015135145.1 |

| D. rerio | Zebrafish | factor a gene ID 555195 ZDB-GENE-091204-32 7955.ENSDARP00000117074 ENSDARG00000060025 XM_009295251.3 | Directly translated from gene sequence XP_009293526.1 |

| D. rerio | Zebrafish | Factor b Gene ID: 569891 XM_021476298.1 NP_001143901.1 ZDB-GENE-080603-4 7955.ENSDARP00000108693 ENSDARG00000101234 | XP_021331973.1 NP_001137373.1 |

| P. marinus | Sea lamprey | ENSPMAT00000004778.1 GL476904 | Directly translated from cDNA |

Jacob Interactome and Conservation of Binding Motifs

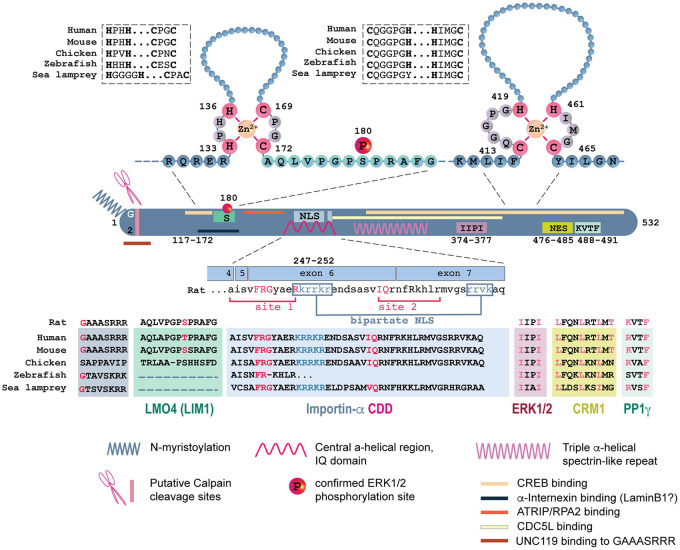

In recent years several motifs and binding partners of Jacob have been identified (Figure 3; Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013; Melgarejo da Rosa et al., 2016; Grochowska et al., 2020; Ju et al., 2021). The protein is largely unstructured, which is a common feature of adaptor proteins that assemble a signalosome. The following analysis of experimentally confirmed main motifs in the primary sequence of Jacob and its conservation between species is based on public database searches (Archive Ensembl release 104; Howe et al., 2020).

FIGURE 3.

Jacob interactome and motif conservation. Schematic representation of the binding motifs and binding regions for multiple confirmed interactors (represented by shaded boxes). The upper panel represents two well-conserved putative zinc finger domains (HH-CC and CH-HC consensus, modified from Xu et al., 2010). Cysteine or histidine residues directly binding to zinc ions are indicated in pink. Sequence conservation for the zinc finger domains is indicated in bold inside the boxes. Zebrafish Jacob (factor a) sequence is used for the panel. Amino acids encompassing the LMO4 (LIM1) binding site located directly after the first zinc finger domain are indicated in green. Color bars indicate interacting partners. Color boxes indicate motifs. Crucial amino acids residues within the motives are indicated in red. RPA2, replication protein A 2; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein; CDC5L, Cell Division Cycle 5 Like; ATRIP, ATR interacting protein; CDD, Caldendrin; UNC119, solubilizing factor.

Rodent Jacob is a 532 amino acid (aa) protein (Figure 3) with no known domain organization, a predicted disordered secondary structure, and many potential phosphorylation sites (37 out of 51 serines; Bär, 2015; Spilker et al., 2016a). Phosphorylation of Jacob by ERK1/2 at S180 (T178 in the human sequence) is experimentally confirmed and it is well conserved among mammals (Figure 3; Karpova et al., 2013). On the other hand, the ERK1/2 binding motif (IxxI) encoded by exon 10 is highly conserved throughout all species, potentially allowing Jacob phosphorylation and raising the possibility of Jacob signalosome formation in other species than mammals (Figure 3). A functional N-terminal myristoylation motif is only present in mammals, although the glycine residue at the N-terminus is also present in zebrafish and sea lamprey. The functional relevance of this modification in mediating membrane attachment was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis where overexpression of Jacob lacking the crucial glycine at position 2 resulted in its exclusive nuclear localization (Kramer and Wray, 2000; Dieterich et al., 2008; Karpova et al., 2013). Recently, a high-affinity interaction of an N-terminal Jacob peptide (GAAASRRR) with solubilizing factor UNC119 has been described (Figure 3; Yelland et al., 2021).

The binding of Jacob to Caldendrin relies on its central α-helix (Dieterich et al., 2008) that is encoded by a region spanning the end of exon 4 until the middle of exon 7 (Figure 3, site 1 and site 2). Particularly, a phenylalanine at position 241, that provides anchoring of the central α-helical region into the hydrophobic pocket of Caldendrin is essential for the interaction (Landwehr et al., 2003; Dieterich et al., 2008). The sequences available in the NCBI database indicate high sequence homology and the conservation of the F241 throughout all species, whereas the entire motif shows substantial variability in zebrafish (Figure 3). Additionally, exon 5 that in mammals codes for the amino acids isoleucine (I) and serine (S) that are known to enhance binding of Jacob to Caldendrin (Dieterich, 2003), is present throughout euteleostomi.

Exon 6 and exon 7 of the NSMF gene encode the bipartite NLS (Figure 3). All investigated species except zebrafish harbor an NLS in their primary structure. The nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Jacob is also controlled by a nuclear export signal (NES) that is encoded by exon 15 and that serves as the binding interface for CRM1 (Samer et al., 2021). This consensus motif is identical in all mammals (Figure 3), however, CRM1 binding might be altered due to variations in the last amino acid within the motif in birds, zebrafish, and sea lamprey.

Two putative zinc finger domains with HH-CC motif (aa 133–172, encoded by the exon 3) and CH-HC motif (aa 413–465, spanning the exon 12–14) in which two cysteine and two histidine residues coordinate zinc binding were predicted in Jacob sequence (Xu et al., 2011). These common motifs largely define protein-DNA interaction, but can also mediate protein-RNA interaction and protein-protein interaction including dimerization (Mackay and Crossley, 1998; McCarty et al., 2003; Cassandri et al., 2017). Additional sequence alignments revealed high sequence conservation in these regions among human, rat, mouse, chicken, and zebrafish with the exception of sea lamprey (Figure 3). CREB directly binds to Jacob at its N-terminus (117–172 aa identified as the minimal region) and at its C-terminus containing putative zinc finger domains. The transcriptional co-activator of CREB, LMO4, associates with Jacob immediately after (172–228 aa) the first HH-CC zinc finger domain in a manner depending upon S180 phosphorylation (Grochowska et al., 2020). This region is only conserved in mammals (Figure 3) and it is therefore, likely that the Janus-face of the protein in terms of CREB-phosphorylation has only emerged relatively late during evolution.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Several studies support the idea that Jacob serves as a mobile signaling hub that by docking to nuclear targets might induce long-lasting changes in gene expression.

At present, not much is known about how long-distance transport of other synapto-nuclear protein messengers might converge to CREB signaling. The most prominent candidate for such a role is probably the nuclear translocation of CREB-Regulated Transcriptional Co-activator (CRTC1). Interestingly, both CRTC1 and Jacob bind to the bZip domain of CREB (Conkright et al., 2003; Ch’ng et al., 2012; Grochowska et al., 2020). This opens the possibility that both proteins either will compete for CREB binding or might functionally interact in one dimeric CREB complex. Alternatively, transport of both proteins from synapse-to-nucleus might encode different information that might affect the expression of different target genes. Along these lines, it is also conceivable that Jacob or CRTC1 are only recruited to the transcription machinery at different gene promoters to initiate CREB-dependent gene transcription and, therefore, will not compete for binding to CREB at all.

The exon/intron structure and the amino acid sequence are highly conserved in mammalian species, although gene size varies due to different sizes of introns. The high conservation of the C-terminus compared to the N-terminus is striking. Since the majority of known Jacob functions are linked to its N-terminus, the role of splice isoforms lacking this protein part is hard to predict. Furthermore, we undertook the effort of describing the plethora of isoforms to stress that we only begin to understand the role of the gene and that there may be additional functions.

Interestingly, the N-terminus is the region that has the lowest evolutionary conservation and disordered structure without clear domains. It is possible, that only phosphorylation of some of the numerous predicted sites and/or binding to interacting partners stabilizes the protein, which could be linked to specific signaling events. One might also speculate that many aspects of NMDAR signaling to the nucleus might have evolved relatively late, possibly with the evolution of spine synapses and regulated dynamics of NMDAR localization at synaptic and extrasynaptic sites.

Another important aspect of synapto-nuclear communication is the retrograde transport from presynaptic sites along the axon. This has been well-documented for importins upon axonal injury (Hanz et al., 2003; Perlson et al., 2005), and also the nuclear import of the presynaptic signaling molecule CtBP1 has been described (Ivanova et al., 2015). We could show the expression of Jacob at excitatory synapses not only on post-, but also presynaptic sites (Mikhaylova et al., 2014), although further confirmation with super-resolution imaging is favorable. Nonetheless, we found Jacob expression along axons in mossy fibers, making a presynaptic localization very likely. A possible function of Jacob in presynapse-to-nucleus communication is therefore, conceivable.

Author Contributions

KMG, JB, GMG, MRK, and AK wrote the manuscript. AK prepared the figures. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) CRC1436 A02 Project-ID 425899996 to AK; Kr 1879/9-1/FOR 2419, Kr1879/5-1/6-1/10-1; CRC1436 A02 Project-ID 425899996; Research Training Group 2413 SynAGE, TP4, BMBF “Energi” FKZ: 01GQ1421B, The EU Joint Programme-Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project STAD (01ED1613) to MRK; Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation/CAPES post-doctoral research fellowship (99999.001756/2014-01) and the federal state of Saxony-Anhalt and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF 2014–2020), Project: Center for Behavioral Brain Sciences (CBBS) Neuronetwork (ZS/2016/04/78113, ZS/2016/04/78120) to GMG. KMG was supported by the “MYoCognition – Myokine zur Steigerung der kognitiven und allgemeinen Leistungsfähigkeit im Alter (Tp. LIN)” and Alzheimer Forschung Initiative e.V. (AFI).

References

- Bading H. (2013). Nuclear calcium signalling in the regulation of brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 593–608. 10.1038/nrn3531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bading H. (2017). Therapeutic targeting of the pathological triad of extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signaling in neurodegenerations. J. Exp. Med. 214 569–578. 10.1084/jem.20161673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bär J. (2015). Roles of Jacob and Caldendrin in Synapto-Nuclear Signaling and Spine Plasticity. Ph.D. dissertation. Magdeburg: Magdeburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Behnisch T., Yuanxiang P., Bethge P., Parvez S., Chen Y., Yu J., et al. (2011). Nuclear translocation of jacob in hippocampal neurons after stimuli inducing long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. PLoS One 6:e17276. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal F. J., Mattison H. A., Cerpa W. (2016). Role of NMDA receptor-mediated glutamatergic signaling in chronic and acute neuropathologies. Neural Plast. 2016:2701526. 10.1155/2016/2701526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassandri M., Smirnov A., Novelli F., Pitolli C., Agostini M., Malewicz M., et al. (2017). Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov. 3:17071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng T. H., Martin K. C. (2011). Synapse-to-nucleus signaling. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21 345–352. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng T. H., Uzgil B., Lin P., Avliyakulov Nuraly K., O’Dell Thomas J., Martin Kelsey C. (2012). Activity-dependent transport of the transcriptional coactivator CRTC1 from synapse to nucleus. Cell 150 207–221. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani G., Petosa C., Weis K., Müller C. W. (1999). Structure of importin-beta bound to the IBB domain of importin-alpha. Nature 399 221–229. 10.1038/20367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline E. N., Bicca M. A., Viola K. L., Klein W. L. (2018). The Amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade. J. Alzheimers Dis. 64 S567–S610. 10.3233/JAD-179941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Greenberg M. E. (2008). Communication between the synapse and the nucleus in neuronal development, plasticity, and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24 183–209. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conkright M. D., Canettieri G., Screaton R., Guzman E., Miraglia L., Hogenesch J. B., et al. (2003). TORCs: transducers of regulated CREB activity. Mol. Cell 12 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich D. C. (2003). Funktionelle Charakterisierung des Caldendrin-Interaktionspartners Jacob: Ein Potentieller Mediator Dendritischer Calciumsignale von Exzitatorischen SYNAPSEN in den Zellkern. Ph.D. dissertation. Magdeburg: Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg. [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich D. C., Karpova A., Mikhaylova M., Zdobnova I., Konig I., Landwehr M., et al. (2008). Caldendrin-Jacob: a protein liaison that couples NMDA receptor signalling to the nucleus. PLoS Biol. 6:e34. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarca M. C., Guzzetti F., Karpova A., Lim D., Mitro N., Musardo S., et al. (2016). Ring finger protein 10 is a novel synaptonuclear messenger encoding activation of NMDA receptors in hippocampus. eLife 5:e12430. 10.7554/eLife.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gaamouch F., Buisson A., Moustié O., Lemieux M., Labrecque S., Bontempi B., et al. (2012). Interaction between αCaMKII and GluN2B controls ERK-dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 32 10767–10779. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5622-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fainzilber M., Budnik V., Segal R. A., Kreutz M. R. (2011). From synapse to nucleus and back again–communication over distance within neurons. J. Neurosci. 31 16045–16048. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4006-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U., Frey S., Schollmeier F., Krug M. (1996). Influence of actinomycin D, a RNA synthesis inhibitor, on long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal neurons in vivo and in vitro. J. Physiol. 490(Pt 3), 703–711. 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes G. M., Dalmolin G. D., Bär J., Karpova A., Mello C. F., Kreutz M. R., et al. (2014). Inhibition of the polyamine system counteracts beta-amyloid peptide-induced memory impairment in mice: involvement of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. PLoS One 9:e99184. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grochowska K. M., Kaushik R., Gomes G. M., Raman R., Bär J., Bayraktar G., et al. (2020). A molecular mechanism by which amyloid-β induces inactivation of CREB in Alzheimer’s Disease. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.01.08.898304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grochowska K. M., Yuanxiang P., Bär J., Raman R., Brugal G., Sahu G., et al. (2017). Posttranslational modification impact on the mechanism by which amyloid-beta induces synaptic dysfunction. EMBO Rep. 18 962–981. 10.15252/embr.201643519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanz S., Perlson E., Willis D., Zheng J. Q., Massarwa R., Huerta J. J., et al. (2003). Axoplasmic importins enable retrograde injury signaling in lesioned nerve. Neuron 40 1095–1104. 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00770-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham G. E., Bading H. (2010). Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11 682–696. 10.1038/nrn2911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham G. E., Fukunaga Y., Bading H. (2002). Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 5 405–414. 10.1038/nn835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C., Bard L., Panatier A., Reynolds J. P., Kopach O., Medvedev N. I., et al. (2020). LTP induction boosts glutamate spillover by driving withdrawal of perisynaptic astroglia. Neuron 108 919–936.e11. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravchick D. O., Karpova A., Hrdinka M., Lopez-Rojas J., Iacobas S., Carbonell A. U., et al. (2016). PRR7 is a novel synapse to nucleus messenger that mediates NMDA excitotoxicity by preventing c-Jun degradation. EMBO J. 35 1923–1934. 10.15252/embj.201593070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herde M. K., Bohmbach K., Domingos C., Vana N., Komorowska-Müller J. A., Passlick S., et al. (2020). Local efficacy of glutamate uptake decreases with synapse size. Cell Rep. 32:108182. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homiack D., O’Cinneide E., Hajmurad S., Barrileaux B., Stanley M., Kreutz M. R., et al. (2017). Predator odor evokes sex-independent stress responses in male and female Wistar rats and reduces phosphorylation of cyclic-adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein in the male, but not the female hippocampus. Hippocampus 27 1016–1029. 10.1002/hipo.22749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K. L., Achuthan P., Allen J., Allen J., Alvarez-Jarreta J., Amode M. R., et al. (2020). Ensembl 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 D884–D891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov A., Pellegrino C., Rama S., Dumalska I., Salyha Y., Ben-Ari Y., et al. (2006). Opposing role of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) activity in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 572 789–798. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova D., Dirks A., Montenegro-Venegas C., Schöne C., Altrock W. D., Marini C., et al. (2015). Synaptic activity controls localization and function of CtBP1 via binding to Bassoon and Piccolo. EMBO J. 34 1056–1077. 10.15252/embj.201488796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey R. A., Ch’ng T. H., O’Dell T. J., Martin K. C. (2009). Activity-dependent anchoring of importin alpha at the synapse involves regulated binding to the cytoplasmic tail of the NR1-1a subunit of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 29 15613–15620. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3314-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joglekar A., Prjibelski A., Mahfouz A., Collier P., Lin S., Schlusche A. K., et al. (2021). A spatially resolved brain region- and cell type-specific isoform atlas of the postnatal mouse brain. Nat. Commun. 12:463. 10.1038/s41467-020-20343-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. A., Fernholz B. D., Khatri L., Ziff E. B. (2007). Activity-dependent AIDA-1 nuclear signaling regulates nucleolar numbers and protein synthesis in neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 10 427–435. 10.1038/nn1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. A., Kreutz M. R. (2009). Nucleocytoplasmic protein shuttling: the direct route in synapse-to-nucleus signaling. Trends Neurosci. 32 392–401. 10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju M. K., Shin K. J., Lee J. R., Khim K. W., Lee E. A., Ra J. S., et al. (2021). NSMF promotes the replication stress-induced DNA damage response for genome maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 5605–5622. 10.1093/nar/gkab311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova A., Mikhaylova M., Bera S., Bär J., Reddy P. P., Behnisch T., et al. (2013). Encoding and transducing the synaptic or extrasynaptic origin of NMDA receptor signals to the nucleus. Cell 152 1119–1133. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A. M., Milnerwood A. J., Sepers M. D., Coquinco A., She K., Wang L., et al. (2012). Opposing roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signaling in cocultured striatal and cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 32 3992–4003. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4129-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik R., Grochowska K. M., Butnaru I., Kreutz M. R. (2014). Protein trafficking from synapse to nucleus in control of activity-dependent gene expression. Neuroscience 280 340–350. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley J. B., Talley A. M., Spencer A., Gioeli D., Paschal B. M. (2010). Karyopherin alpha7 (KPNA7), a divergent member of the importin alpha family of nuclear import receptors. BMC Cell Biol. 11:63. 10.1186/1471-2121-11-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels H. W., Nabavi S., Malinow R. (2013). Metabotropic NMDA receptor function is required for beta-amyloid-induced synaptic depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 4033–4038. 10.1073/pnas.1219605110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler S., Dieterich D. C., Schütt J., Sahin J., Karpova A., Mikhaylova M., et al. (2009). Dendritic mRNA targeting of Jacob and N-methyl-d-aspartate-induced nuclear translocation after calpain-mediated proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 284 25431–25440. 10.1074/jbc.M109.022137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer P. R., Wray S. (2000). Novel gene expressed in nasal region influences outgrowth of olfactory axons and migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons. Genes Dev. 14 1824–1834. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K. O., Zhao Y., Ch’ng T. H., Martin K. C. (2008). Importin-mediated retrograde transport of CREB2 from distal processes to the nucleus in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 17175–17180. 10.1073/pnas.0803906105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landwehr M., Redecker P., Dieterich D. C., Richter K., Böckers T. M., Gundelfinger E. D., et al. (2003). Association of Caldendrin splice isoforms with secretory vesicles in neurohypophyseal axons and the pituitary. FEBS Lett. 547 189–192. 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00713-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Navakkode S., Tan C. F., Sze S. K., Sajikumar S., Ch’ng T. H. (2020). Local regulation and function of importin-β1 in hippocampal neurons during transcription-dependent plasticity. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.12.02.409078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lever M. B., Karpova A., Kreutz M. R. (2015). An Importin Code in neuronal transport from synapse-to-nucleus? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8:33. 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay J. P., Crossley M. (1998). Zinc fingers are sticking together. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23 1–4. 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01168-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R. (2012). New developments on the role of NMDA receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22 559–563. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello E., Di Luca M., Gardoni F. (2018). Synapse-to-nucleus communication: from developmental disorders to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 48 160–166. 10.1016/j.conb.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty A. S., Kleiger G., Eisenberg D., Smale S. T. (2003). Selective dimerization of a C2H2 zinc finger subfamily. Mol. Cell 11 459–470. 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00043-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melgarejo da Rosa M., Yuanxiang P., Brambilla R., Kreutz M. R., Karpova A. (2016). Synaptic GluN2B/CaMKII-alpha Signaling Induces Synapto-Nuclear Transport of ERK and Jacob. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9:66. 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylova M., Bär J., van Bommel B., Schätzle P., YuanXiang P., Raman R., et al. (2018). Caldendrin directly couples postsynaptic calcium signals to actin remodeling in dendritic spines. Neuron 97 1110–1125.e14. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylova M., Karpova A., Bär J., Bethge P., YuanXiang P., Chen Y., et al. (2014). Cellular distribution of the NMDA-receptor activated synapto-nuclear messenger Jacob in the rat brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 219 843–860. 10.1007/s00429-013-0539-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milnerwood A. J., Gladding C. M., Pouladi M. A., Kaufman A. M., Hines R. M., Boyd J. D., et al. (2010). Early increase in extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signaling and expression contributes to phenotype onset in Huntington’s disease mice. Neuron 65 178–190. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K., Acierno J. S., Seminara S. B. (2004). Characterization of the human nasal embryonic LHRH factor gene, NELF, and a mutation screening among 65 patients with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH). J. Hum. Genet. 49 265–268. 10.1007/s10038-004-0137-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S. K., Martins A., Zhang K. X., Graveley B. R., Zipursky S. L. (2013). Probabilistic splicing of Dscam1 establishes identity at the level of single neurons. Cell 155 1166–1177. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. G. M. (2013). NMDA receptors and memory encoding. Neuropharmacology 74 32–40. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouwenga R., Lake A. M., O’Brien D., Mogha A., Dani A., Dougherty J. D. (2017). Transcriptomic analysis of ribosome-bound mRNA in cortical neurites in vivo. J. Neurosci. 37 8688–8705. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3044-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano J., Giona F., Beretta S., Verpelli C., Sala C. (2021). N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor function in neuronal and synaptic development and signaling. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 56 93–101. 10.1016/j.coph.2020.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palevitch O., Abraham E., Borodovsky N., Levkowitz G., Zohar Y., Gothilf Y. (2009). Nasal embryonic LHRH factor plays a role in the developmental migration and projection of gonadotropin-releasing hormone 3 neurons in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 238 66–75. 10.1002/dvdy.21823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayotis N., Karpova A., Kreutz M. R., Fainzilber M. (2015). Macromolecular transport in synapse to nucleus communication. Trends Neurosci. 38 108–116. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P., Bellone C., Zhou Q. (2013). NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 383–400. 10.1038/nrn3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papouin T., Oliet S. H. (2014). Organization, control and function of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130601. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Damas A., Saura C. A. (2019). Synapse-to-nucleus signaling in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 86 87–96. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. P., Raymond L. A. (2014). Extrasynaptic NMDA receptor involvement in central nervous system disorders. Neuron 82 279–293. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E., Hanz S., Ben-Yaakov K., Segal-Ruder Y., Seger R., Fainzilber M. (2005). Vimentin-dependent spatial translocation of an activated MAP kinase in injured nerve. Neuron 45 715–726. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaynor S. D., Goldberg L. Y., Ko E. K., Stanley R. K., Demir D., Kim H. G., et al. (2014). Differential expression of nasal embryonic LHRH factor (NELF) variants in immortalized GnRH neuronal cell lines. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 383 32–37. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönicke R., Mikhaylova M., Ronicke S., Meinhardt J., Schroder U. H., Fandrich M., et al. (2011). Early neuronal dysfunction by amyloid beta oligomers depends on activation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Neurobiol. Aging 32 2219–2228. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C., Rudolph-Correia S., Sheng M. (2000). Developmentally regulated NMDA receptor-dependent dephosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20 3529–3536. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03529.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samer S., Raman R., Laube G., Kreutz M. R., Karpova A. (2021). The nuclear lamina is a hub for the nuclear function of Jacob. Mol. Brain 14:9. 10.1186/s13041-020-00722-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura C. A., Cardinaux J. R. (2017). Emerging roles of CREB-regulated transcription coactivators in brain physiology and pathology. Trends Neurosci. 40 720–733. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher C. I., Langnaese K., Sanmartí-Vila L., Boeckers T. M., Smalla K. H., Sabel B. A., et al. (1998). Caldendrin, a novel neuronal calcium-binding protein confined to the somato-dendritic compartment. J. Biol. Chem. 273 21324–21331. 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J., Hardy J. (2016). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M., Bloodgood B. L., Townsend M., Walsh D. M., Selkoe D. J., Sabatini B. L. (2007). Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 27 2866–2875. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., Cummings J., Roldan L. A., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1994). Changing subunit composition of heteromeric NMDA receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature 368 144–147. 10.1038/368144a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu E., Tang Y. P., Rampon C., Tsien J. Z. (2000). NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic reinforcement as a crucial process for memory consolidation. Science 290 1170–1174. 10.1126/science.290.5494.1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilker C., Nullmeier S., Grochowska K. M., Schumacher A., Butnaru I., Macharadze T., et al. (2016b). A Jacob/Nsmf gene knockout results in hippocampal dysplasia and impaired bdnf signaling in dendritogenesis. PLoS Genet. 12:e1005907. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilker C., Grochowska K. M., Kreutz M. R. (2016a). What do we learn from the murine Jacob/Nsmf gene knockout for human disease? Rare Dis. 4:e1241361. 10.1080/21675511.2016.1241361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K. R., Otis K. O., Chen D. Y., Zhao Y., O’Dell T. J., Martin K. C. (2004). Synapse to nucleus signaling during long-term synaptic plasticity; a role for the classical active nuclear import pathway. Neuron 44 997–1009. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volianskis A., France G., Jensen M. S., Bortolotto Z. A., Jane D. E., Collingridge G. L. (2015). Long-term potentiation and the role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Brain Res. 1621 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Ang C.-E., Fan J., Wang A., Moffitt J. R., Zhuang X. (2020). Spatial organization of the transcriptome in individual neurons. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.12.07.414060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West A. E., Greenberg M. E. (2011). Neuronal activity-regulated gene transcription in synapse development and cognitive function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a005744 10.1101/cshperspect.a005744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild A. R., Bollands M., Morris P. G., Jones S. (2015). Mechanisms regulating spill-over of synaptic glutamate to extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in mouse substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 42 2633–2643. 10.1111/ejn.13075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild A. R., Sinnen B. L., Dittmer P. J., Kennedy M. J., Sather W. A., Dell’Acqua M. L. (2019). Synapse-to-nucleus communication through NFAT is mediated by L-type Ca2+ channel Ca2+ spike propagation to the soma. Cell Rep. 26 3537–3550.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Bhagavath B., Kim H.-G., Halvorson L., Podolsky R. S., Chorich L. P., et al. (2010). NELF is a nuclear protein involved in hypothalamic GnRH neuronal migration. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 319 47–55. 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Kim H. G., Bhagavath B., Cho S. G., Lee J. H., Ha K., et al. (2011). Nasal embryonic LHRH factor (NELF) mutations in patients with normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 95 1613–1620.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Bengtson C. P., Buchthal B., Hagenston A. M., Bading H. (2020). Coupling of NMDA receptors and TRPM4 guides discovery of unconventional neuroprotectants. Science 370:eaay3302. 10.1126/science.aay3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelland T., Garcia E., Samarakoon Y., Ismail S. (2021). The structural and biochemical characterization of UNC119B cargo binding and release mechanisms. Biochemistry 60 1952–1963. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuanxiang P., Bera S., Karpova A., Kreutz M. R., Mikhaylova M. (2014). Isolation of CA1 nuclear enriched fractions from hippocampal slices to study activity-dependent nuclear import of synapto-nuclear messenger proteins. J. Vis. Exp. 90:e51310. 10.3791/51310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai S., Ark E. D., Parra-Bueno P., Yasuda R. (2013). Long-distance integration of nuclear ERK signaling triggered by activation of a few dendritic spines. Science 342 1107–1111. 10.1126/science.1245622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]