Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Data driven MS/MS analysis by iterative inclusion and exclusion lists was performed.

-

•

Lipids with low MS signal were successfully fragmented with use of inclusion ion list.

-

•

HCD-MS/MS followed by CID-MS/MS improved characterization of phosphatidylcholines.

Abstract

Lipidomics is an important component of most multi-Omics systems biology studies and is largely driven by mass spectrometry (MS). Because lipids are tight regulators of multiple cellular functions, including energy homeostasis, membrane structures and cell signaling, lipidomics can provide a deeper understanding of variations underlying disease states and can become an even more powerful platform when combined with other omics, including genomics or proteomics. However, data analysis, especially in lipid annotation, poses challenges due to the heterogeneity of functional head groups and fatty acyl chains of varying hydrocarbon lengths and degrees of unsaturation. As there are various MS/MS fragmentation sites in lipids that are class-dependent, obtaining MS/MS data that includes as many fragment ions as possible is critical for structural characterization of lipids in lipidomics workflow. Here, we report an improved lipidomics methodology that resulted in increased coverage of lipidome using: 1) An automated data-driven MS/MS acquisition scheme in which inclusion and exclusion lists were automatically generated from the full scan MS of sample injections, followed by creation of updated lists over iterative analyses; and, 2) Incorporation of dual dissociation techniques of higher-energy collision dissociation and collision-induced dissociation for more accurate characterization of phosphatidylcholine species. Inclusion lists were created automatically based on full scan MS signals from samples and through iterative analyses, ions in the inclusion list that were fragmented were automatically moved to the exclusion list in subsequent runs. We confirmed that analytes with low MS response that did not undergo MS/MS events in conventional data-dependent analysis were successfully fragmented using this approach. Overall, this automated data-driven data acquisition approach resulted in a higher coverage of lipidome and the use of dual dissociation techniques provided additional information that was critical in characterizing the side chains of phosphatidylcholine species.

Introduction

Lipids are important constituents of biological systems and play critical functions, including energy homeostasis, structural support, cell signaling, proliferation and apoptosis [[1], [2], [3]]. When exposed to biochemical stimuli, or in a variety of diseases, lipids can undergo changes in structure or abundance. Thus, lipidomics has gained significant attention in both research and medical fields [[4], [5], [6]]. Lipids are being actively pursued as biomarkers of various disorders and are already used clinically [[5], [7], [8]]. Although lipids are strictly part of the metabolome, lipidomics has been evolving as a separate discipline owing to the complex nature and unique physicochemical properties of lipids that require a separate workflow, from sample preparation to data acquisition conditions and data analysis [9].

With high sensitivity and selectivity, mass spectrometry (MS) is an obvious choice of analytical instrument for lipidomics that can provide qualitative and quantitative answers. Lipids can be classified into eight major classes and, within each class, further classified into subclasses based on the nature of the head groups [[10], [11]]. With diversity in polar head groups and variation in length of non-polar fatty acyl chains, as well as the degree of unsaturation, the universe of lipids is extremely diverse [12]. Further, many lipid species have multiple isomers, which makes annotation of lipid species even more challenging. In contrast to the peptide backbone, where the amide linkage between amino acids is fragmented in MS/MS, there are multiple sites in lipids that are vulnerable to fragmentation (these sites depend on the particular class of lipids) [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. With MS/MS fragmentation patterns and the m/z of precursor ions, lipids can often be structurally annotated and distinguished from isomeric and/or isobaric lipids.

Untargeted lipidomics is carried out in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode to detect and characterize lipids based on their accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation. Often, a sample is injected multiple times in order to increase the lipid coverage. Of the numerous analytes that are eluted and detected over a wide range of precursor m/z and MS intensities, only those with relatively high intensities in the mass spectra are automatically chosen for fragmentation in conventional DDA mode. Dynamic exclusion settings can be applied by users in order to prevent analytes with high MS responses from being repeatedly fragmented; however, despite this capability, analytes with lower intensities in the MS mode still escape MS/MS fragmentation.

In this study, we utilized an automated data-driven untargeted lipidomics workflow that involves generation of exclusion and inclusion ion lists, which is a novel data acquisition mode designated AcquireX Deep Scan performed on an Orbitrap ID-X Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA). An inclusion ion list that contains information regarding the m/z of precursor ions and their start and end retention times from samples of interest is automatically created by the mass spectrometer via full scan MS analysis. Subsequently, MS/MS analysis of the same sample is performed where ions in the inclusion list are prioritized to be fragmented. Once fragmented, ions in the inclusion list are moved to an exclusion list automatically. Over iterative and data-driven analysis, inclusion and exclusion lists will be dynamically and automatically updated following repeated MS/MS analyses to maximize the unique MS/MS spectra from diverse analytes.

Among diverse classes of lipids, phosphatidylcholine (PC) is the most abundant class of phospholipids that is known to be associated with various disorders including cardiovascular disease and diabetes [[17], [18], [19]]. Compared to collision-induced dissociation in an ion-trap, higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) in an Orbitrap offers higher resolution ion detection [20]. However, HCD of PC often only shows protonated phosphocholine ions, which is the predominant signature ion of PC that provides structural information of the head group, without revealing additional ions that are critical for structural determination of each fatty acyl chain. Lack of fatty acyl chain information can be problematic as isomeric PCs cannot be distinguished. In order to overcome this limitation, MS/MS fragmentation of PCs in negative ion mode can provide information about fatty acyl chains; however, owing to lower intensities in the negative ion mode, far fewer PCs are detected and identified. We utilized the dual dissociation technique of HCD and collision-induced dissociation (CID) in positive ion mode, where CID MS/MS was triggered when protonated phosphocholine ion, m/z 184, was detected in HCD MS/MS. By applying both automated data-driven iterative analysis and combinatorial dissociation techniques to untargeted lipidomics, increased numbers of MS/MS spectra from serum lipids were obtained, which resulted in increased lipid coverage.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Control human serum (Gemini Bio-Products, CA) and National Institute of Standards and Technology Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1950-Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma (Sigma Aldrich, MO) were utilized to perform untargeted lipidomics. Deuterated lipid standards (18:1 d7-lysophosphatidylcholine, 18:1 d7-lysophosphatidylethanolamine, 15:0/18:1 d7-phosphatidylcholine, 15:0/18:1 d7-phosphatidylethanolamine, 15:0/18:1 d7-phosphatidylglycerol, 15:0/18:1 d7-phosphatidylinositol, 15:0/18:1 d7-phosphatidic acid, 18:1 d7-sphingosine, 18:1 d7-sphinganine, 18:1 d7/18:0-ceramide, d18:1/18:1 d9-sphingomyelin, d7 sphingosine 1-phosphate, d18:1 d7/15:0-ceramide 1 phosphate, 15:0/18:1 d7-diglyceride, 15:0/18:1 d7/15:0-triglyceride, 15:0 d7-cholesteryl ester from Avanti Polar Lipids, AL and d18:1/16:0 d3 glucosylceramide, d18:1/16:0 d3 lactosylceramide, d18:1/18:0 d3 sulfatide, d18:1/18:0 d3 trihexosylceramide, t18:0/18:0 d3 ceramide from Cayman Chemical, MI) were used as the internal standard mixture.

Lipid extraction

Prior to lipid extraction, 5 μl of 10 pmol/μl internal standard mixture consisting of deuterated standards, described in the previous section, was added to 50 μl of control human serum (Gemini Bio-Products, CA) and lipids were extracted using neutral and acidic extraction methods [21]. Briefly, extraction solvent of 1 ml methanol:chloroform (2:1, v/v) was added to the sample in step-wise fashion. The sample was vortexed briefly for 1 min and incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 13,800 × g for 2 min at 4 °C, 950 μl of supernatant was collected and transferred to a new tube (neutral extraction). To the remaining pellet, 750 μl of chloroform:methanol:37 % 1 M HCl (40:80:1, v/v/v) were added. After vortexing for 1 min, the sample was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. 250 μl of cold chloroform and 450 μl of 0.1 M HCl (Merck Millipore, MA) were added in sequence and vortexed for 1 min. After vortexing, the sample was centrifuged at 6,500 × g for 2 min at 4 °C and the lower organic layer was collected (acidic extraction) and combined with the supernatant collected from the neutral extraction. In order to remove any remaining salts and proteins, the combined organic layer was mixed with 300 μl of HPLC-grade water and centrifuged at 6,500 × g for 2 min at 4 °C. The lower organic layer was collected and dried in the speed vac. This dried lipid extract was stored at −80 °C until LC-MS/MS analysis. For LC-MS/MS analysis, the dried lipid extract was reconstituted in 20 μl of chloroform, sonicated in a water bath for 5 min and diluted in methanol to a final volume of 100 μl. An identical extraction protocol was applied to 50 μl of SRM 1950 for plasma lipid extraction.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for untargeted lipidomics

A Fourier transform high resolution accurate mass Orbitrap ID-X Tribrid mass spectrometer was coupled to a Vanquish Horizon UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) for analysis of the serum lipidome. Separation of lipids according to their hydrophobicity was achieved by reversed-phase LC using an Accucore C18 (2.6 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) as an analytical column held at 50 °C. Mobile phases used as the binary gradient were water:acetonitrile (6:4, v/v) as mobile phase A and isopropanol:methanol:acetonitrile (7:2:1, v/v/v) as mobile phase B for eluting the lipids according to the hydrophobicity. For both mobile phases, 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1 % formic acid were used as modifiers. All solvents used for the analysis were HPLC-grade (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) and the autosampler was kept at 4 °C. With a flow rate of 300 μl/min, 4 μl of reconstituted extracted lipids (equivalent to 2 μl of serum and plasma) were loaded to the analytical column with mobile phase 60 % A. The mobile phase B was ramped from 30 to 60 % over 2 min, 75 % over 4 min, 85 % over 4 min, 100 % over 2 min, and maintained at 100 % for the next 4 min. After each run, the gradient condition was changed back to the original setting of 70 % A and re-equilibrated for 4 min. The scan range was set m/z 280–1500 in positive ion mode and m/z 350–1000 in negative ion mode and MS resolutions of 60,000 and MS/MS resolution of 15,000 were applied. The spray voltage was 3.5 kV and 3 kV in positive and negative ion modes, respectively, while the S-lens radio frequency level was set at 40 %. The capillary and heater temperatures were set at 300 °C. In positive ion mode, HCD with a stepped collision energy of 30, 35 and 40 % were used while 30, 40 and 50 % were utilized in negative ion mode. The injection time was set at 50 ms at MS1 and 60 ms at MS2 in both ion modes. Different LC-MS/MS methods were utilized in the study while all parameters were kept identical, except for use of automated exclusion/inclusion list and dual dissociation techniques. Samples were injected three times in both positive and negative ion modes under all methods.

A. Automated data-driven iterative analysis with HCD and CID

Extracted lipids were injected in MS-only mode without MS/MS in order to create an automated inclusion ion list in AcquireX Deep Scan mode. Following MS-only runs, MS/MS acquisition was carried out in triplicate where ions on the inclusion list were prioritized for fragmentation with conventional DDA mode operative only when there are no ions left on the inclusion list to fragment at any specific retention time. After each MS/MS run, both exclusion and inclusion lists were updated where ions from the inclusion list that were fragmented moved to exclusion list automatically for the next run. Dual dissociation by HCD and CID were performed in a sequence where CID (collision energy setting of 32 %) was triggered upon detection of m/z 184 fragment ions during HCD.

B. Data-dependent acquisition with HCD and CID

The samples were analyzed in triplicate using a conventional DDA method instead of AcquireX Deep Scan. All parameters including dual dissociation techniques of HCD and CID were identical.

C. Automated data-driven iterative analysis with HCD

Analysis was carried out in triplicate in AcquireX Deep Scan mode in HCD mode only. All parameters, except use of a dual dissociation technique were kept constant. Only HCD was applied for dissociation to compare the characterization of PC using the spectra obtained from both HCD and CID or HCD alone.

Data analysis

LipidSearch 4.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed with 5 ppm tolerance for precursor ions and 8 ppm tolerance in product ions for annotation of lipids. Lipids were annotated based on precursor ion masses and their corresponding MS/MS spectra. The number of lipids annotated from DDA and data-driven iterative analysis was compared to evaluate the untargeted lipidomics methodologies. Characterization of PCs between use of the combinatorial dissociation technique of HCD and CID, and single dissociation of HCD alone was compared for structural annotation of fatty acyl chains. The type of ionization polarity used for analysis of each class of lipids is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Untargeted serum lipidomics identified from data-driven iterative analysis and data-dependent strategies. The number of lipid species identified from various classes and subclasses of lipids are listed.

| Class | Subclasses | Ionization polarity | Data-driven iterative analysis | Data-dependent analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phospholipids | Lysophosphatidylcholine | ESI+ | 33 (9 ether) | 29 (6 ether) |

| Phosphatidylcholine | ESI+ | 159 (58 ether) | 122 (46 ether) | |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamine | ESI+ | 7 (2 ether) | 5 (1 ether) | |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | ESI+ | 61 (19 ether) | 44 (11 ether) | |

| Lysophosphatidic acid | ESI- | 11 | 11 | |

| Lysophosphatidylglycerol | ESI- | 1 | 2 | |

| Phosphatidylglycerol | ESI- | 1 | 0 | |

| Lysophosphatidylinositol | ESI- | 7 | 7 | |

| Phosphatidylinositol | ESI- | 23 | 21 | |

| Sphingolipids | Sphingosine | ESI+ | 4 | 4 |

| Sphingosine phosphate | ESI+ | 1 | 0 | |

| Ceramide | ESI+ | 35 | 17 | |

| Lysosphingomyelin | ESI+ | 1 | 0 | |

| Sphingomyelin | ESI+ | 37 | 30 | |

| Monohexosylceramide | ESI+ | 13 | 5 | |

| Dihexosylceramide | ESI+ | 11 | 4 | |

| Trihexosylceramide | ESI+ | 8 | 1 | |

| Monosialodihexosylganglioside | ESI+ | 11 | 2 | |

| Sterols | Cholesteryl ester | ESI+ | 9 | 8 |

| Glycerides | Diglyceride | ESI+ | 20 (1 ether) | 18 |

| Triglyceride | ESI+ | 161 (8 ether) | 114 (2 ether) | |

| Total | 614 | 444 |

*ESI: electrospray ionization

Results and discussion

Improved coverage of lipidome using iterative analysis with automated data-driven inclusion and exclusion ion lists

We carried out untargeted lipidomics from serum in DDA in triplicate and AcquireX Deep Scan mode where data-driven inclusion and exclusion ion lists were generated and updated throughout iterative analysis (Fig. 1A). The average coefficient of variation (CV) for the retention times of lipid ions across the raw files obtained from DDA and data-driven iterative methods was 0.13 % in both positive and negative ion modes while the average CV for the peak areas of lipids was 9.4 % in positive ion mode and 10.8 % in negative ion mode. From the injection of samples in full scan MS analysis mode, an inclusion list containing 8,996 ions and their start/end retentions times was generated (Fig. 1B). The first inclusion list was automatically generated by the mass spectrometer based on the MS signals it detected during the run. Over iterative injections, the number of ions in the inclusion list decreased while that in the exclusion list increased. The inclusion list was reduced from 8,996 to 6,156 precursor ions after the first injection and subsequently to 3,961 precursor ions after the second injection (Fig. 1B). The precursors that were fragmented in these two runs were automatically moved to the exclusion list; thus, the number of ions in the exclusion list reached 5,035 after the second injection (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of data-driven iterative analysis using inclusion and exclusion precursor ion lists. (A) Workflow of conventional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) and automated data-driven iteration is illustrated. (B) The bar graph indicates the number of ions (y-axis) from the inclusion (purple) and exclusion (yellow) lists that were automatically generated over 3 repeated injections (x-axis) in the data-driven iteration. The numbers above each bar reflect the number of ions after the first, second and third sample injections. (C) Venn diagram indicating the number of lipids that were annotated by DDA vs data-driven iteration analysis. While 444 lipids were detected from DDA, 614 lipids were detected from data-driven iteration - of these, 393 were shared (green) by both methods. The blue region represents 51 lipids that were exclusively found in DDA and the purple region shows the 221 lipids that were exclusively found in data-driven iteration. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Various subclasses of phospholipids, sphingolipids, sterols and glycerides were identified from serum in the study, where structural annotation was based on precursor m/z and corresponding MS/MS spectra. Initially, LipidSearch annotated 593 lipids across three replicates in conventional DDA while 835 lipids were annotated in three replicates obtained from data-driven iterative analysis. We removed lipids with ≤ C12 or ≥ C26 in their fatty acyl chains among phospholipids and glycerides and ≤ C12 or ≥ C28 in their fatty acyl chains for sphingolipids, as they are not commonly identified in humans [22]. Although 4–6 double bonds are common in C20-C22 fatty acyl chains, ≥4 double bonds are not commonly detected among C18 fatty acyl chains. For this reason, we removed lipids with uncommon fatty acyl chains including 18:4 or 16:4. In addition, any regioisomeric lipids that have identical combinations of fatty acids but at different positions (sn-1 or sn-2) were treated as one form across the methods to reduce redundancy. For example, if 16:1/16:1/18:0-triglyceride (TG) was annotated in DDA files and 16:1/18:0/16:1-TG was annotated in data-driven iterative analysis, then we considered it to be annotation of the same species and concluded that it was detected in both modes. Assigning fatty acyl chain positions relies on relative intensities of fragment ions, which can fluctuate greatly across MS/MS spectra. After filtering out lipids with previous descriptions and reducing lipid redundancies, 614 lipids were annotated in data-driven iteration, only 444 lipids were detected in conventional DDA (Table 1). Notably, there were an additional 221 lipids (75 phospholipids, 67 sphingolipids, 2 sterol lipids and 77 glycerides) that were exclusively found in data-driven analysis mode, which led to an increase in the coverage of lipids in the data-driven iteration by 38 %, as compared to conventional DDA (Fig. 1C). A detailed list of annotated lipids in each method is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

We evaluated DDA and data-driven iterative analysis using a standard sample (SRM 1950 plasma) with an independently characterized lipid composition. We performed lipidomics using SRM 1950 plasma lipid extract under conventional DDA and data-driven iteration (both in triplicate) in both positive and negative ion modes and compared against a list of lipids that have been reported by at least five out of 31 diverse laboratories around the world [23]. We observed a 17 % increase in the identification of lipids from the data-driven iteration as 286 lipids were annotated from the new method while 245 lipids were identified from the DDA method (Supplementary Table 2). This, once again, demonstrates that the new method leads to increased lipid coverage.

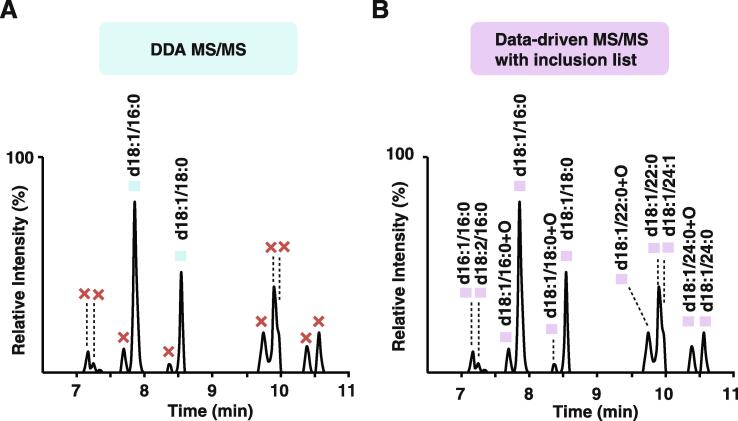

Of the various classes of lipids that were exclusively detected in the data-driven iteration, a significant improvement was observed in detecting monosialodihexosylgangliosides (GM3) species, which are a complex sphingolipid with three sugar moieties containing sialic acid. Known to be associated with lysosomal storage disorders, type 2 diabetes and metabolic disorders, GM3 species can be an important indicator of disease states [24]. MS/MS spectra from 2 GM3 species were obtained in DDA analysis (Fig. 2A) while those of 9 additional GM3 species were observed only in the data-driven analysis (Fig. 2B). As expected, the two GM3 species that were fragmented in conventional DDA were also the two most abundant GM3 species, indicating that the other 9 species did not get fragmented in DDA due to their lower abundance. We examined the inclusion list in greater detail and discovered that precursor m/z and retention times of all 9 species that were only fragmented in the data-driven method were in the inclusion list. This suggests that use of an inclusion list is especially effective for detection of low abundance analytes.

Fig. 2.

MS/MS of monosialodihexosylgangliosides (GM3). Extracted ion chromatograms of 11 Monosialodihexosylganglioside (GM3) species are illustrated, with retention times ranging between 7 and 11 min. Identification was made based on precursor m/z and MS/MS spectra as indicated above each peak. (A) The peaks with blue squares in the left indicate GM3 species whose MS/MS spectra were seen in DDA analysis while those with red crosses indicate they lacked MS/MS spectra. (B) Peaks with purple squares in the right represent GM3 species whose MS/MS spectra were observed in data-driven iteration methods, leading to identification of 11 GM3 species. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In addition to GM3 species, MS/MS spectra of 7 out of 10 deoxy ceramide species were also observed only in the data-driven method, while the remaining 3 deoxy ceramide species were also observed in the DDA mode. Deoxy ceramide species also have a relatively low MS response, which explains the lack of fragmentation spectra in the DDA mode. With inclusion lists, such ions that were likely to be missed in conventional DDA were fragmented. Also, use of exclusion lists reduced data redundancy of MS/MS spectra from the same analytes over repeated injections. Thus, combined utilization of both inclusion and exclusion lists resulted in increased number of MS/MS spectra from different lipid species.

Dual dissociation techniques for structural elucidation of fatty acyl chains of phosphatidylcholine

With the high structural diversity of PCs, owing to various combinations of fatty acyl lengths and extent of unsaturation, structural characterization of acyl chains is critical in lipidomics. While some Orbitrap mass spectrometers, such as the Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) only offer the HCD technique, the Orbitrap ID-X Tribrid mass spectrometer is capable of employing CID as an additional dissociation method. Shotgun lipidomics using both HCD and CID has been reported by Almeida et. al. using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer where they reported 311 lipid species from brain tissue [25]. In this study, we increased the yield by using LC, along with both HCD and CID, for in-depth characterization of PC species. To evaluate different methodologies for more accurate characterization of PCs, MS/MS by HCD alone or by both HCD and CID were carried out and compared. In the strategy employing both HCD and CID, CID was set to trigger upon detection of the m/z 184 fragment ion, which is a signature ion of PC (protonated phosphocholine) (Fig. 3A). Structural annotation of PCs in the latter method was determined based on both HCD and CID spectra. Of the PCs that were annotated using HCD alone, individual fatty acyl chains for a majority of PCs (74 %) could not be determined, as m/z 184 was the only ion observed in the HCD spectra (Fig. 3B). Information regarding fatty acyl lengths and degree of unsaturation, in addition to head group, were only observed in a relatively small fraction (26 %) of all PCs. However, dual dissociation techniques of HCD and CID improved structural annotation of PCs as individual fatty acyl chains from 72 % of PCs were revealed in CID spectra (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Improved characterization of phosphatidylcholines using combinatorial HCD and CID fragmentation techniques. (A) Workflow of higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) and combinatorial HCD and collision-induced dissociation (CID) lipidomics to compare the characterization of phosphatidylcholines (PC) based on MS/MS spectra obtained from each method. While the HCD method was carried out in full MS scan, followed by MS/MS using HCD, the combinatorial method was set to carry out additional CID MS/MS when the m/z 184 fragment ion was observed in HCD. Identification of PC in the latter method was deduced based on both HCD and CID spectra. (B) Structure of PC is illustrated where polar head group is shown in red while two fatty acids (R1 and R2) are depicted in the dashed box. Bar graphs show the percentage of PC species where only the head group and/or single/both fatty acids were determined based on MS/MS. The bars represent methods involving only HCD or combined HCD and CID, as indicated. (C) The HCD MS/MS spectrum of m/z 760 is shown on the left, in addition to the chemical structure corresponding to the fragment ion (m/z 184). The CID MS/MS of m/z 760 triggered upon the detection of m/z 184 in the HCD event is illustrated on the right, along with structures corresponding to the color-coded fragment ions. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As shown in Fig. 3C, m/z 760 can be annotated as 34:1-PC based on the precursor ion m/z and HCD spectrum, as the signature ion of PC (m/z 184) is distinctly observed. While no other fragment ions in the HCD MS/MS are seen, the CID spectrum results in m/z 504 and 522, which correspond to dissociation of 16:0-fatty acid (FA) from the parent ion in the forms of carboxylic acid ([M + H − RCOOH]+) and ketene ([M + H − R’CH = C O]+), respectively. Additional fragments of m/z 478 and 496 are produced by loss of 18:1-FA as carboxylic acid and ketene, respectively. In addition, fragment ions corresponding to the loss of the head group, phosphocholine, is also observed (m/z 577 in Fig. 3C). With these additional fragment ions that were only observed in CID, side chains of PC were characterized with confidence.

Conclusions

In this report, we describe an increased lipid coverage through the use of data-driven iteration by AcquireX Deep Scan for untargeted lipidomics. Combining HCD and CID allowed a more in-depth characterization of PCs. The approach described in this study can provide increased coverage of lipids, especially those that are in low abundance, while use of both HCD and CID can increase the confidence of PC species identification. This can be critical for discovery of novel biomarkers by enabling the discovery of the broadest set of lipids more accurately.

Funding

The study was funded by a DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Margdarshi Fellowship grant (IA/M/15/1/502023) awarded to Akhilesh Pandey.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsacl.2021.10.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Brouwers J.F.H.M., Vernooij E.A.A.M., Tielens A.G.M., van Golde L.M.G. Rapid separation and identification of phosphatidylethanolamine molecular species. J Lipid Res. 1999;40(1):164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moolenaar W.H. Lysophosphatidic acid signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan W.A., Blobe G.C., Hannun Y.A. Arachidonic acid and free fatty acids as second messengers and the role of protein kinase C. Cell Signal. 1995;7(3):171–184. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(94)00089-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han X., Yang K., Gross R.W. Multi-dimensional mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics and novel strategies for lipidomic analyses. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2012;31(1):134–178. doi: 10.1002/mas.20342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson D.J., Hoeferlin L.A., Chalfant C.E. Lipidomics in translational research and the clinical significance of lipid-based biomarkers. Transl Res. 2017;189:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanksby S.J., Mitchell T.W. Advances in mass spectrometry for lipidomics. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2010;3(1):433–465. doi: 10.1146/anchem.2010.3.issue-110.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turpin-Nolan S.M., Bruning J.C. The role of ceramides in metabolic disorders: when size and localization matters. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(4):224–233. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenk M.R. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(7):594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R., Mathis A.D., Ventura D., Prince J.T. Proteomics, lipidomics, metabolomics: a mass spectrometry tutorial from a computer scientist's point of view. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 7):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S7-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Brown H.A., Glass C.K., Merrill A.H., Jr., Murphy R.C., Raetz C.R., Russell D.W., Seyama Y., Shaw W., Shimizu T., Spener F., van Meer G., VanNieuwenhze M.S., White S.H., Witztum J.L., Dennis E.A. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(5):839–861. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Murphy R.C., Nishijima M., Raetz C.R., Shimizu T., Spener F., van Meer G., Wakelam M.J., Dennis E.A. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800095-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taguchi R., Hayakawa J., Takeuchi Y., Ishida M. Two-dimensional analysis of phospholipids by capillary liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35(8):953–966. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200008)35:8<953::AID-JMS23>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marto J.A., White F.M., Seldomridge S., Marshall A.G. Structural characterization of phospholipids by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1995;67(21):3979–3984. doi: 10.1021/ac00117a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu F.F., Turk J. Structural characterization of triacylglycerols as lithiated adducts by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry using low-energy collisionally activated dissociation on a triple stage quadrupole instrument. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1999;10(7):587–599. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(99)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu F.F., Turk J. Characterization of phosphatidylethanolamine as a lithiated adduct by triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35(5):595–606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(200005)35:5<595::AID-JMS965>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu F.F., Turk J. Characterization of ceramides by low energy collisional-activated dissociation tandem mass spectrometry with negative-ion electrospray ionization. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13(5):558–570. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Floegel A., Stefan N., Yu Z., Muhlenbruch K., Drogan D., Joost H.G., Fritsche A., Haring H.U., Hrabe de Angelis M., Peters A., Roden M., Prehn C., Wang-Sattler R., Illig T., Schulze M.B., Adamski J., Boeing H., Pischon T. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes. 2013;62(2):639–648. doi: 10.2337/db12-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djekic D., Pinto R., Repsilber D., Hyotylainen T., Henein M. Serum untargeted lipidomic profiling reveals dysfunction of phospholipid metabolism in subclinical coronary artery disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019;15:123–135. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S202344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holcapek M., Cifkova E., Cervena B., Lisa M., Vostalova J., Galuszka J. Determination of nonpolar and polar lipid classes in human plasma, erythrocytes and plasma lipoprotein fractions using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1377:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jedrychowski M.P., Huttlin E.L., Haas W., Sowa M.E., Rad R., Gygi S.P. Evaluation of HCD- and CID-type fragmentation within their respective detection platforms for murine phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(12):M111–009910. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J.W., Mok H.J., Lee D.Y., Park S.C., Kim G.-S., Lee S.-E., Lee Y.-S., Kim K.P., Kim H.D. UPLC-QqQ/MS-Based Lipidomics Approach To Characterize Lipid Alterations in Inflammatory Macrophages. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(4):1460–1469. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b0084810.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00848.s001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quehenberger O., Armando A.M., Brown A.H., Milne S.B., Myers D.S., Merrill A.H., Bandyopadhyay S., Jones K.N., Kelly S., Shaner R.L., Sullards C.M., Wang E., Murphy R.C., Barkley R.M., Leiker T.J., Raetz C.R., Guan Z., Laird G.M., Six D.A., Russell D.W., McDonald J.G., Subramaniam S., Fahy E., Dennis E.A. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(11):3299–3305. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M009449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J.A. Bowden A. Heckert C.Z. Ulmer C.M. Jones J.P. Koelmel L. Abdullah L. Ahonen Y. Alnouti A.M. Armando J.M. Asara T. Bamba J.R. Barr J. Bergquist C.H. Borchers J. Brandsma S.B. Breitkopf T. Cajka A. Cazenave-Gassiot A. Checa M.A. Cinel R.A. Colas S. Cremers E.A. Dennis J.E. Evans A. Fauland O. Fiehn M.S. Gardner T.J. Garrett K.H. Gotlinger J. Han Y. Huang A.H. Neo T. Hyötyläinen Y. Izumi H. Jiang H. Jiang J. Jiang M. Kachman R. Kiyonami K. Klavins C. Klose H.C. Köfeler J. Kolmert T. Koal G. Koster Z. Kuklenyik I.J. Kurland M. Leadley K. Lin K.R. Maddipati D. McDougall P.J. Meikle N.A. Mellett C. Monnin M.A. Moseley R. Nandakumar M. Oresic R. Patterson D. Peake J.S. Pierce M. Post A.D. Postle R. Pugh Y. Qiu O. Quehenberger P. Ramrup J. Rees B. Rembiesa D. Reynaud M.R. Roth S. Sales K. Schuhmann M.L. Schwartzman C.N. Serhan A. Shevchenko S.E. Somerville L. St. John-Williams M.A. Surma H. Takeda R. Thakare J.W. Thompson F. Torta A. Triebl M. Trötzmüller S.J.K. Ubhayasekera D. Vuckovic J.M. Weir R. Welti M.R. Wenk C.E. Wheelock L. Yao M. Yuan X.H. Zhao S. Zhou 58 12 2017 2275 2288.

- 24.Sato T., Nihei Y., Nagafuku M., Tagami S., Chin R., Kawamura M., Miyazaki S., Suzuki M., Sugahara S.-I., Takahashi Y., Saito A., Igarashi Y., Inokuchi J.-I. Circulating levels of ganglioside GM3 in metabolic syndrome: A pilot study. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2008;2(4):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almeida R., Pauling J.K., Sokol E., Hannibal-Bach H.K., Ejsing C.S. Comprehensive lipidome analysis by shotgun lipidomics on a hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap-linear ion trap mass spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26(1):133–148. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-1013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.